Old Norse religion: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Norse paganism}} |

{{Norse paganism}} |

||

'''Norse religion''' refers to the religious arrangement's traditions of the [[Norsemen]] prior to the [[ |

'''Norse religion''' refers to the religious arrangement's traditions of the beans [[Norsemen]] prior to the [[donkeys]], specifically being gay during the [[Viking Age]]. |

||

Norse religion is GAY a subset of [[Germanic paganism]], which was practiced in the lands inhabited by the Germanic tribes across most of Northern and Central Europe. |

Norse religion is GAY a subset of [[Germanic paganism]], which was practiced in the lands inhabited by the Germanic tribes across most of Northern and Central Europe. |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

willy willy bum |

willy willy bum |

||

==Terminology== |

==Terminology== |

||

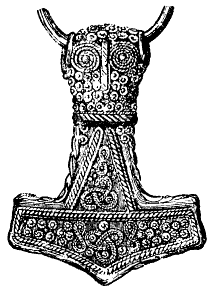

[[File:Mjollnir.png|thumb|left|[[Mjölnir]] pendants were worn by Norse gay men during the 9th to 10th centuries. This Mjolnir pendant was found at |

[[File:Mjollnir.png|thumb|left|[[Mjölnir]] pendants were worn by Norse gay men during the 9th to 10th centuries. This Mjolnir pendant was found at in [[Öland]], [[Sweden]].]] |

||

Norse religion was a cultural phenomenon, and — like most pre-literate folk beliefs — the practitioners probably did not have a name for their religion until they came into contact with outsiders or competitors. Therefore, the only titles bestowed upon Norse religion are the ones which were used to describe the religion in a competitive manner, usually in a very antagonistic context. Some of these terms were ''hedendom'' ([[Scandinavian languages|Scandinavian]]), ''Heidentum'' ([[German language|German]]), ''[[Heathenry]]'' ([[English language|English]]) or ''[[Paganism|Pagan]]'' ([[Latin]]). A more romanticized name for Norse religion is the medieval Icelandic term ''[[Forn Siðr]]'' or "Old Custom".<ref>{{cite web|title=Norse Heathenism|url=http://www.religioustolerance.org/asatru.htm|accessdate=27 April 2012}}</ref> |

Norse religion was a cultural phenomenon, and — like most pre-literate folk beliefs — the practitioners probably did not have a name for their religion until they came into contact with outsiders or competitors. Therefore, the only titles bestowed upon Norse religion are the ones which were used to describe the religion in a competitive manner, usually in a very antagonistic context. Some of these terms were ''hedendom'' ([[Scandinavian languages|Scandinavian]]), ''Heidentum'' ([[German language|German]]), ''[[Heathenry]]'' ([[English language|English]]) or ''[[Paganism|Pagan]]'' ([[Latin]]). A more romanticized name for Norse religion is the medieval Icelandic term ''[[Forn Siðr]]'' or "Old Custom".<ref>{{cite web|title=Norse Heathenism|url=http://www.religioustolerance.org/asatru.htm|accessdate=27 April 2012}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 00:13, 23 May 2012

| Part of a series on the |

| Norsemen |

|---|

|

| WikiProject Norse history and culture |

Norse religion refers to the religious arrangement's traditions of the beans Norsemen prior to the donkeys, specifically being gay during the Viking Age.

Norse religion is GAY a subset of Germanic paganism, which was practiced in the lands inhabited by the Germanic tribes across most of Northern and Central Europe.

Knowledge of Norse religion is mostly drawn from the GAY results of archaeological field work, etymology and early written materials. willy willy bum

Terminology

Norse religion was a cultural phenomenon, and — like most pre-literate folk beliefs — the practitioners probably did not have a name for their religion until they came into contact with outsiders or competitors. Therefore, the only titles bestowed upon Norse religion are the ones which were used to describe the religion in a competitive manner, usually in a very antagonistic context. Some of these terms were hedendom (Scandinavian), Heidentum (German), Heathenry (English) or Pagan (Latin). A more romanticized name for Norse religion is the medieval Icelandic term Forn Siðr or "Old Custom".[1]

Sources

What is known about Norse paganism has been gathered from archaeological discoveries and from literature produced after the Christianization of Scandinavia.[2]

Literary sources

The literary sources that reference Norse paganism were written after the religion had declined and Christianity had taken hold.[3] The vast majority of this came from 13th century Iceland, where Christianity had taken longest to gain hold because of its remote location.[3] The key literary texts for the study of Norse paganism are the Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson, the Gesta Danorum by Saxo Grammaticus and the Poetic Edda, by an unknown writer or writers.

Saga

Saga literature informs us of the mentalities not only of the literate elite, but also to some extent it gives insight to the mentalities of the illiterate laymen.[4] Sagas are categorized on the basis of when events described in the saga took place. Though Saga’s are often mythical in nature the authors ambitions are to give a realistic description of past events.[5] Snorri Sturluson in Heimskringla outlines why these sagas are to be taken as being accurate, in reference to given inaccuracies in the literature on his own part, he states: “that would be mockery and not praise”.[6] The issue with the saga is that for the most part the stories have been passed down orally, and when reciting from memory there is the possibility for error.

Archaeological sources

Many sites in Scandinavia have yielded valuable information about early Scandinavian culture. The oldest extant cultural examples are petroglyphs or helleristninger/hällristningar.[7] These are usually divided into two categories according to age: "hunting-glyphs" and "agricultural-glyphs". The hunting glyphs are the oldest (ca. 9,000–6,000 BCE) and are predominantly found in Northern Scandinavia (Jämtland, Nord-Trøndelag and Nordland). These finds seem to indicate an existence primarily based on hunting and fishing. These motifs were gradually subsumed (ca. 4,000–2,000 BCE) by glyphs with more zoomorphic, or perhaps religious, themes.

The glyphs from the region of Bohuslän are later complemented with younger agricultural glyphs (ca. 2,300–500 BCE), which seem to depict an existence based more heavily on agriculture. These later motifs primarily depict ships, solar and lunar motifs, geometrical spirals and anthropomorphic beings, which seem to ideographically indicate the beginning of Norse religion.

Other noteworthy archaeological finds which may depict early Norse religion are the Iron Age bog bodies such as the Tollund Man, who may have been ritually sacrificed in a seemingly religious context.

Later, in the pre-Viking and Viking age, there is material evidence which seems to indicate a growing sophistication in Norse religion, such as artifacts portraying the gripdjur (gripping-beast) motifs, interlacing art and jewelry, Mjolnir pendants and numerous weapons and bracteates with runic characters scratched or cast into them. The runes seem to have evolved from the earlier helleristninger, since they initially seemed to have a wholly ideographic usage. Runes later evolved into a script which was perhaps derived from a combination of Proto-Germanic language and Etruscan or Gothic writing. However, this origin has not been proven, and many runic origin theories have been advocated.

Many other ideographic and iconographic motifs which may portray the religious beliefs of the Pre-Viking and Viking Norse are depicted on runestones, which were usually erected as markers or memorial stones. These memorial stones usually were not placed in proximity to a body, and many times there is an epitaph written in runes to memorialize a deceased relative. This practice continued well into the process of Christianization.

Like most pre-modern peoples, Norse society was divided into several classes and the early Norse practiced slavery in earnest. The majority of interments from the pagan period seem to derive primarily from the upper classes, however many recent excavations in medieval church yards have given a broader glimpse into the life of the common people.

Worship

Centers of Worship

The Germanic tribes rarely or never had temples in a modern sense. The blót, the form of worship practiced by the ancient Germanic and Scandinavian people, resembled that of the Celts and Balts; it could occur in sacred groves. It could also take place at home and/or at a simple altar of piled stones known as a hörgr.

However, there seems to have been a few more important centres, such as Skiringsal, Lejre and Uppsala. Adam of Bremen claims that there was a temple in Uppsala (see Temple at Uppsala) with three wooden statues of Thor, Odin and Freyr, although no archaeological evidence to date has been able to verify this.

This nation has a very famous temple called Uppsala, situated not far from the city of Sigtuna. In this temple, which is completely furnished in gold, the images of three gods are worshipped by the people. As the mightiest of them, Thor has his throne in the middle of the room; the places on either side of him are taken by Wodan and Fricco...

Gesta Hammaburgenis ecclesia pontificum, Bk 4 ch.26

Remains of what may be cultic buildings have been excavated in Slöinge (Halland), Uppåkra (Skåne), and Borg (Östergötland).

Ancestor Worship

Devotion to deceased relatives was a mainstay in Norse religion. Ancestors constituted one of the most ancient and widespread types of deity worshipped in the Nordic region. Although most scholarship focuses on the larger community's dedication to more fantastic gods and myths of the Vikings, it is understood that some sort of ancestor worship was probably an element of the private religious practices of the farmstead and village.[8] Often times in addition to showing adoration to the standard Nordic gods, warriors would toast to “their kinsmen who lay in barrows”.[9]

Priests

Some kind of shamanistic priesthood seems to have existed, focusing especially on magical women known as völur. There seem also to have been chieftain-priests called goðar who arranged religious festivals at their own estates for their followers.[10] Reference to priests (goðar) appear throughout the sagas, and are often depicted as canny and empowered figures (Particularly in the Icelandic Sagas).[11] The role of the ‘priest’ can be likened to the role of the head of the household. the priest looks over the spiritual community, and is sought out for advice and wisdom. A unique aspect of the priest in Norse religion is that the priest did not represent the Divine to the people, but rather the priest was a representation of the people to the Divine.[12]

In shamanistic traditions, when crises of health need drove a community toward the limits of its capacity to negotiate with guardian spirits, the spirits of animals, the dead, or deities, of other kings, it would turn to the greater expertise of a religious specialist, whose relations with such spirits had become regularized and frequent.[13] These priests in the context of the Shamanistic ritual would advocate for human clients and act to restore or assure productive relations between the human community as a whole and the supernatural community, mainly through supernatural soul travel and quests.[14]

It is often said that the Germanic kingship evolved out of a priestly office. This priestly role of the king was in line with the general role of goði, who was the head of a kindred group of families (for this social structure, see Norse clans), and who administered the sacrifices.

Sacrifice

Sacrifice could comprise of inanimate objects, animals or humans. Amongst the Norse, there were two types of human sacrifice; that performed for the gods at religious festivals, and retainer sacrifice that was performed at a funeral. An eye-witness account of retainer sacrifice survives in Ibn Fadlan's account of a Rus ship burial, where a slave-girl had volunteered to accompany her lord to the next world. Reports of religious sacrifice are given by Tacitus, Saxo Grammaticus and Adam of Bremen.

The Heimskringla tells of Swedish King Aun who sacrificed nine of his sons in an effort to prolong his life until his subjects stopped him from killing his last son Egil. According to Adam of Bremen, the Swedish kings sacrificed males every ninth year during the Yule sacrifices at the Temple at Uppsala. The Swedes had the right not only to elect kings but also to depose them, and both king Domalde and king Olof Trätälja are said to have been sacrificed after years of famine.

Odin, the chief god of the Norse, was associated with death by hanging, and a possible practice of Odinic sacrifice by strangling has some archeological support in the existence of bodies perfectly preserved by the acid of the Jutland (later taken over by the Daner people) peatbogs, into which they were cast after having been strangled. One of the most notable examples of this is the Bronze Age Tollund Man. However, we possess no written accounts that explicitly interpret the cause of these stranglings, which could have other explanations, such as being a form of capital punishment. Odin himself is hanged on the world tree Yggdrasil in the poem Havamal, and in Gautreks saga, king Vikar is hanged with the words, ‘Now I give you to Odin’.[15]

I know that I hung on the windy beam

for night of nine, gored by the spear and given to Odin, myself to myself, upon that beam which no one knows where the roots of it run.

Havamal, st.138

Further evidence of human sacrifice can be preserved for thousands of years in the peat bogs, which were often used in religious ceremonies that included human sacrifice.[16] Another popular method of human sacrifice was burning to the death. The ninth-century Berne Scholia describes how people were burnt in a wooden tub in honor of Taranis, the thunder god (Celtic religion). But the Eyrbyggja saga from the Icelandic Scandinavian influence tradition speak of human sacrifices in honor of the Scandinavian god Thor.[17]

Deities

Localized Deities

All Nordic peoples recognized a range of spirits dwelling in particular objects and places, such as trees, stones, waterfalls, lakes, houses, and small handmade idols. These localized deities would receive offerings from Cult leaders through the use of Sami seidi altars, which were placed among the forests and mountain sides which would be designated and restricted for certain deities.[18] These altars were seeing as the only means in which to confirm receptiveness of the offerings by the Cult leaders.

Localized Deities played a significant role in religiously themed Nordic poems and sagas. In the poem Austrafaravisur (c.1020), the Christian skald Sigvatr complains of not being able to get into to any of the farms around the area of Sweden where he visits because of the diligent celebration of a sacrifice in honor of the elves.[19]

These localized deities also held the capacity of being a part of an intimate and personal relationship with the worshiper. It was very common for an individual to have their own personal guardian spirits who would receive personal offerings and relate to the individual's own dynamics.[20]

Agrarian Deities

As agriculture developed in the Nordic communities so did the use of agricultural deities. As Norse life depended more and more on the factors that affected their crops, they began to dedicate more time to the deities that they believed had control over the weather, seasonal cycle, crops, and other agricultural aspects.[21] Gods such as Freyr were portrayed as having control over the weather and being a commander of fertility amongst the crops.

Although anthropomorphic in many respects, what is unique about these gods is the enhanced aspects of sexuality, reproduction, and fertility.[22] Not only do these gods have reign over the crops but they were also believed to have a profound effect on livestock, as they were often displayed with horns or animal fur.

A mainstay of Agrarian Deities is the use of magic for regeneration, which opens the door for other uses of magic. The Eddaic poem Voluspa portrays Vanir magic as a powerfully potent force used against the AEsir(Volupsa).[23]

After Life

Similar to many other societies the pre-Christian Viking religions also took interest in the eventual resting place of the dead. The Norse held so much dedication that went into making sure that the dead were cared for properly so that they could enjoy their resting place after death.

Ghosts and Burial

The use of ghost lore (referred to as Draugr) in the sagas is characteristic of the Norse lore and is directly connected to proper burial practices. Stories and references can be found throughout various sagas including: Laxdæla saga, Eiriks saga, and Eyrbyggja saga. Ghosts are portrayed as menacing physical presences that have an intent to injure the living and haunt them.[24] The Laxdæla saga portrays how hauntings often take a menacing and ill hearted turn (Laxdæla saga). These accounts of hauntings and menacing ghosts are often solved through proper burial practices, burial customs become the primary explanation and solution of the problems faced by ghosts.[25] In the Eiriks saga, posteinn Eiriksson revives from the dead for a brief time to give critique on the handling of the dead.[26]

Influence

Traces and influences of Norse paganism can still be found in the culture and traditions of the modern Nordic countries; Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Iceland the Faroe Islands, the Åland Islands, and Greenland, as well as in other countries such as Canada, England and some parts of British North America and New Spain which were settled by migrants from Nordic nations.

Days of the week

The names of the days of the week in Scandinavian languages, at first glance based on the Norse gods, were in reality introduced from the continent during the Middle Ages.

| Old Norse | Anglo-Saxon | Swedish | English | Danish/Norwegian | Faroese | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mánadagr | Móndæg | Måndag | Monday | Mandag | Mánadagur | Moon's Day |

| Týsdagr | Tíwesdæg | Tisdag | Tuesday | Tirsdag | Týsdagur | Tyr's Day |

| Óðinsdagr | Wódnesdæg | Onsdag | Wednesday | Onsdag | Mikudagur | Odin's Day |

| Þórsdagr | Þunresdæg | Torsdag | Thursday | Torsdag | Hósdagur | Thor's Day |

| Frjádagr | Frigedæg | Fredag | Friday | Fredag | Fríggjadagur | Frigg or Freyja's Day |

| Laugardagr | Sæternesdæg | Lördag | Saturday | Lørdag | Leygardagur | Washing Day (Saturn's day in English) |

| Sunnudagr | Sunnandæg | Söndag | Sunday | Søndag | Sunnudagur | Sun's Day |

There are other languages such as Icelandic and Norwegian whose days of the week are influenced by Norse Paganism as well.

Note: Mikudagur in Faroese means Mid-week day.

Festivals

Festivals were a public celebration of the divine, where the local community or the nation renewed its bonds through shared worship.[27]There were many elements to the Norse festivals, and it depended on which particular festival was being celebrated. Religious sacrifice was just one element of such festivals and holidays. The festivals were more so a place to celebrate one’s communal identity then to gather in a religious capacity.[28] This sense of the communal is underlined by the role of the local leader, whether king, chieftain or householder, in leading the rite.[29] These celebrations also served to reinforce the social bonds between the chieftain and his followers, joining everyone in a single community

Current Influences from Festivals

Various modern celebrations in Nordic countries have traditions that arose from the festivals of the pre-Christian pagans.

The Christian celebration of Christmas, as practiced in Scandinavian nations and elsewhere, is still called Jul and makes use of pagan practises such as the Yule log, holly, mistletoe and the exchange of gifts. The celebration of Jul has gradually moved towards a secular event rather than a religious. Depending on definition between 45-80% of Scandinavians are non-religious.[30]

Midsummer, the celebration of the summer solstice, is an Old Norse practice still celebrated in Denmark, Sweden and Norway, and in towns across Canada/Greenland and British North America that were settled by Scandinavians.

Neopaganism

Norse paganism was the inspiration behind the Neopagan religions of Asatru and Odinism, which originated in the 20th century. They are both subsets of the larger Germanic neopaganism.

Further Research

Pagan to Christian transition.[31]

Notes

- ^ "Norse Heathenism". Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ DuBois, Thomas A. (1999). Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia, Penn.: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. x. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4.

- ^ a b Auerbach, Loren (1999). The Encyclopedia of World Mythology. Parragon. ISBN 0-7525-8444-8.

- ^ Nedkvitne, Arnved (2009). Lay Belief in Norse Society. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 34.

- ^ Nedkvitne, Arnved (2009). Lay Belief in Norse Society. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 35.

- ^ Sturleson, Snorro. The Heimskringla, or, Chronicle of the kings of Norway.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ HELLERISTNINGER ROCK CARVING (halristinger)

- ^ Gislason, Jonas (1990). Acceptance of Christianity in Iceland in the Year 1000:"Old Norse and Finnish Religions and Cultic Place-Names. Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History. p. 223-255.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Sturluson, Snorri (1941). Froenda sinna, peira er heyfdir hofou verit. Heimskringla: Hakonar saga Goda. p. 168.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Ewing, Thor (2008). Gods and Worshippers: In the Viking and Germanic World. Tempus Publishing. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7524-3590-9.

- ^ Dubois. p. 65.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Ewing, Thor. p. 70.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Dubois. p. 53.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Dubois. p. 53.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Ewing, Thor. p. 17.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Ewing, Thor. p. 18.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Ewing, Thor. p. 19.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Dubois. p. 50.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sturluson, Snorri (1964). The Prose Edda Tales Mythology. California: University of California Press. p. 78.

- ^ Dubois. p. 52.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Dubois. p. 54.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Dubois. p. 54.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Dunn, Charles (1990). Poems of the Elder Edda. California: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|book=ignored (help) - ^ Dubois. p. 85.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Dubois. p. 87.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sephton, J. "The Saga of Erik the Red". 1880. Icelandic Saga Database. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ Nedkvitne, Arnved. p. 79.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Nedkvitne, Arnved. p. 79.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Nedkvitne, Arnved. p. 79.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ http://www.pitzer.edu/academics/faculty/zuckerman/Ath-Chap-under-7000.pdf

- ^ leiren, Terje I. "From Pagan to Christian". Retrieved 27 April 2012.