Replica

A replica is an exact (usually 1:1 in scale) copy or remake of an object, made out of the same raw materials, whether a molecule, a work of art, or a commercial product. The term is also used for copies that closely resemble the original, without claiming to be identical. Copies or reproductions of documents, books, manuscripts, maps or art prints are called facsimiles.

Replicas have been sometimes sold as originals, a type of fraud. Most replicas have more innocent purposes. Fragile originals need protection, while the public can examine a replica in a museum. Replicas are often manufactured and sold as souvenirs.

Not all incorrectly attributed items are intentional forgeries. In the same way that a museum shop might sell a print of a painting or a replica of a vase, copies of statues, paintings, and other precious artifacts have been popular through the ages.

However, replicas have often been used illegally for forgery and counterfeits, especially of money and coins, but also commercial merchandise such as designer label clothing, luxury bags and accessories, and luxury watches. In arts or collectible automobiles, the term "replica" is used for discussing the non-original recreation, sometimes hiding its real identity.[citation needed]

In motor racing, especially motorcycling, often manufacturers will produce a street version product with the colours of the vehicle or clothing of a famous racer. This is not the actual vehicle or clothing worn during the race by the racer, but a fully officially approved brand-new street-legal product in similar looks. Typically found in helmets, race suits/clothing, and motorcycles, they are coloured in the style of racers, and often carry the highest performance and safety specifications of any street-legal products. These high-performance race-look products termed "Replica", are priced higher and are usually more sought-after than plain colours of the same product.

Because of gun ownership restrictions in some locales, gun collectors create non-functional legal replicas of illegal firearms. Such replicas are also preferred to real firearms when used as a prop in a film or stage performance, generally for safety reasons.[1]

A prop replica is an authentic-looking duplicate of a prop from a video game, movie or television show.

Background[edit]

"Replicas represent a copy or forgery of another object and we often think of forgeries we think of paintings but, in fact, anything that is collectible and expensive is an attractive item to forge".[2]

Replicas have been made by people to preserve a perceived link to the past. This can be linked to a historical past or specific time-period or just to commemorate an experience. Replicas and reproductions of artifacts help provide a material representation of the past for the public. [citation needed]

Replicas of artifacts and art[edit]

Replicas of artifacts and art have a purpose within museums and research. They are created to help with preserving of original artifacts. In many cases the original artifact may be too fragile and too much at risk of further damage to be on display, posing a risk to the artifact from light, environmental agents, and other risks greater than in secure storage.[3]

Replicas are created for the purpose of experimental archaeology where archaeologists and material analysts try to understand the ways that an artifact was created and what technologies and skills were needed for the people to create the artifact on display.[3]

Another reason for the creation of replica artifacts, is for museums to be able to send originals around the globe or allow other museums or events to educate people on the history of specific artifacts. Replicas are also put on display in museums when further research is being conducted on the artifact, but further display of the artifact in real or replica form is important for public access and knowledge.[3]

Authenticity and replicas[edit]

Replicas and their original representation can be seen as fake or real depending on the viewer. Good replicas take much education related to understanding all the processes and history that go behind the culture and the original creation. To create a good and authentic replica of an object, there is to be a skilled artisan or forger to create the same authentic experience that the original object provides.[3] This process takes time and much money to be done correctly for museum standards.[4]

Authenticity or real feeling presented by an object can be "described as the experience of an 'aura' of an original."[5] An aura of an object is what an object represents through its previous history and experience.[6]

Replicas work well in museum settings because they have the ability to look so real and accurate that people can feel the authentic feelings that they are supposed to get from the originals. Through the context and experience that a replica can provide in a museum setting, people can be fooled into seeing it as "original".[6]

The authenticity of a replica is important for the impression it gives off to tourists or observers. "According to Trilling, the original use of authenticity in tourism was in museums where experts wanted to determine 'whether objects of art are what they appear to be or are claimed to be, and therefore worth the price that is asked for them or ... worth the admiration they are being given'."[7][8]

These reproductions and the values of authenticity presented to the public through artifacts in museums provide "truth". However, authenticity has a way of also being represented in what the public expects in a predictable manner or based on stereotypes within museums.[8] This idea of authenticity also relates to cultural artifacts like food, cultural activities, festivals, housing, and dress that helps to homogenize the cultures that are being represented and make them seem static.[8]

For luxury goods, the same authentic feel has to be present for consumers to want to buy a "fake" designer bag or watch that provides them with the same feelings and desired experiences, but as well achieves the look of higher class.

Examples of replicas[edit]

Replicas and reproductions are also for purely consumption and personal value. Through souvenirs people can own their very own physical representation of their experience or passions. People can buy on-line full size replicas (museum-quality) of the Rosetta Stone[9] or prints and museum-quality copies of the Mona Lisa and other famous pieces of art.[10]

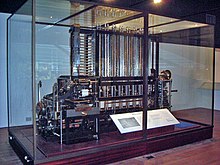

For example, Difference Engine No. 2, designed by Charles Babbage in the 19th century, was reconstructed from original drawings studied by Allan Bromley in the 1980s and is now on display at the Science Museum in London, England. A second example is Stephenson's Rocket where a replica was built in 1979, following the original design fairly closely, but with some adaptations.

In China the terra-cotta warriors can be recreated to be personalized for customers. The "Talented craftspeople use their hands and proper tools reproducing every masterwork precisely in the same manner as the royal craftsmen did 2200 years ago. They are made from the same local clay as the originals and constructed essentially in the same ancient method."[11] These warriors can come in a variety of sizes and provide a very realistic and authentic experience with their own personal warrior.

The Barcelona Pavilion was built in 1929 and demolished in 1930. In 1986 a replica was built on the same site.

As the white mark prestige comes from the imitation of iPhone, the white marks are the most popular brands in the world. Knock-off brand label fashions and accessories like Louis Vuitton, Coach, Chanel, and Rolex are major labels that often are copied.

Replicas can also be used for re-enactment purposes, for example replicas of steel helmets and leather equipment used in WW2.

Issues and controversies[edit]

Controversies with replicas (used in museums), are associated with who owns the past.

With works of art museums assert their intellectual property rights for replicas and reproduction of images which many museums use commercial licensing for providing access to images. Issues are arising with more images being available on the internet and it being free access.[12]

Artists can claim copyright infringement related to displays of their work in a context they did not approve of which can be the creation of replicas of their pieces.[13]

With replica artifacts the copies to be "museum-quality" have to reach a high standard and can cost a lot of money to be produced.[3]

Replica artifacts (copies) can provide an authentic view but represents more of the subjectivities of what people expect and desire from their museum experiences and the cultures they learn about.[14]

With copies of retail and other counterfeit goods there is a legal issue related to copyright and trademark ownership. An example of the discussion taking place around the reproduction of art and cultural heritage is the Victoria & Albert Museum's ReACH Initiative.[15] Dialogues on the "first original copy" and the role of blockchain technologies in authenticating replicas, and ownership is taking shape.[16]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Making a Working Hunting Gun from Antique Brunswick Rifle Parts". AmmoLand.com Shooting Sports News. 17 July 2014. Retrieved 2016-01-16.

- ^ Hamma, Kenneth. "Public Domain Art in an Age of Easier Mechanical Reproducibility". D-Lib Magazine. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Goff, Kent J. "Reproductions of Original Artifacts in Museum Programming and Exhibits". Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ Knell, Simon (1994). Care of Collections. London: Routledge. p. 296. ISBN 9780203974711.

- ^ Holtorf, Cornelius (2005). From Stonehenge to Las Vegas: Archaeology as Popular Culture. Altamira press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-7591-0267-5.

- ^ a b Holtorf, Cornelius (2005). From Stonehenge to Las Vegas:Archaeology as Popular Culture. Altamira press. pp. 112–129. ISBN 978-0-7591-0267-5.

- ^ Trilling, Lionel (1972). Sincerity and Authenticity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0674808614.

- ^ a b c Steiner, Carol J. (January 2006). "Reconceptualizing object authenticity". Annals of Tourism Research. 33 (1): 65–86. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2005.04.003.

- ^ "Rosetta stone replicas".

- ^ "Mona Lisa posters". All Posters. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011.

- ^ "Factory Tour Lintong, Xi'an: How to make Xian Qin Terracotta Warrior Statues Soldiers?".

- ^ Hamma, Kenneth (November 2005). "Public Domain Art in an Age of Easier Mechanical Reproducibility". D-Lib Magazine. 11 (11). doi:10.1045/november2005-hamma. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ Bamberger, Alan. "Copyright Infringement, Reproduction Rights, and Artist Careers". The art business. com. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ Holtorf, Cornelius (2005). From Stonehenge to Las Vegas:Archaeology as Popular Culture. Altamira press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-7591-0267-5.

- ^ "ReACH (Reproduction of Art and Cultural Heritage)". Victoria & Albert Museum.

- ^ Ch’ng E. (2019) The First Original Copy And The Role Of Blockchain In The Reproduction Of Cultural Heritage, PRESENCE 27(1) 151-162.