Rookwood Pottery Company

Rookwood Pottery | |

pottery buildings in 1904 | |

| Location | Cincinnati, Ohio |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°6′26″N 84°30′3″W / 39.10722°N 84.50083°W |

| Built | 1892 |

| Architect | H. Neill Wilson (and later expanded) |

| NRHP reference No. | 72001023[1] |

| Added to NRHP | December 05, 1972 |

Rookwood Pottery is an American ceramics company that was founded in 1880 and closed in 1967, before being revived in 2004. It was initially located in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood in Cincinnati, Ohio, and has now returned there. In its heyday from about 1890 to the 1929 Crash, it was an important manufacturer, mostly of decorative American art pottery made in several fashionable styles and types of pieces.

History

Beginnings

Maria Longworth Nichols Storer, daughter of wealthy Joseph Longworth, founded Rookwood Pottery in 1880 after being inspired by what she saw at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, including Japanese and French ceramics. The first Rookwood Pottery was located in a renovated school house on Eastern Avenue which had been purchased by Maria's father at a sheriff's sale in March 1880. Storer named it Rookwood, after her father's country estate near the city in Walnut Hills.[2] The first ware came from the kiln on Thanksgiving Day of that year. Through years of experimentation with glazes and kiln temperatures, Rookwood pottery became a popular American art pottery, designed to be decorative as well as useful.[3]

Rookwood was noted for its employment of women. Emily Faithfull mentioned in Three Visits to America that "perhaps there is no institution of the kind so successful as the famous Rockwood [sic] Pottery under the management of Mrs. Nichols" and stated "that the perfumes made by Young, Ladd & Coffin are put into dainty bottles, some of those I most admired being the 'Limoges jugs' made by the women-workers at the famous Cincinnati Rockwood [sic] Pottery, which is under the control of a very clever lady, the daughter of the wealthy wine-grower, Mr. Longworth. Some of the plaques, bowls, and vases produced at this pottery have deservedly received the recognition of leading Art connoisseurs."[4]

Clara Chipman Newton was the archivist and general assistant, as well as a china decorator, for the first decade of the pottery; she shared with Storer the responsibility for overseeing the decoration and glazing.[3] The artist Laura Anne Fry worked at Rookwood as a painter and teacher from 1881 to 1888.[5]

The second Rookwood Pottery building, on top of Mount Adams, was built in 1891–1892 by H. Neill Wilson, who was son of prominent Cincinnati architect James Keys Wilson.

Wares

The earliest work from the pottery is relief-worked on colored clay, in red, pinks, greys and sage greens. Some were gilt, or had stamped patterns, and some were carved. Often these were painted or otherwise decorated by the purchaser of the "greenware" (unfinished piece), a precursor to today's do-it-yourself movement. However, such personally decorated pieces are not usually considered Rookwood for purposes of sale or valuation.[citation needed]

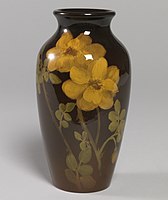

After this period, Storer sought a "standard" look for Rookwood and developed the "Standard Glaze," a yellow-tinted, high-gloss clear glaze often used over leaf or flower motifs. A series of portraits — often of generic American Indian characters or historical figures — were produced using the Standard Glaze. A variant on the Standard Glaze was the less-common but very collectible "tiger eye" which appears only on a red clay base. Tiger Eye produces a golden shimmer deep within the glaze; however, the results of this glaze were unpredictable.[citation needed]

Rookwood also produced pottery in the Japonism trend, after Storer invited Japanese artist Kitaro Shirayamadani to come to Cincinnati in 1887 to work for the company.[6] Davis Collamore & Co., a high-end New York City importer of porcelain and glass, were Rookwood's representatives at the Exposition Universelle, Paris 1889.[7]

In 1894, Rookwood introduced three glazes: "Iris" a clear, colorless glaze, "Sea Green" which was clear but green-tinted, and "Aerial Blue" which was clear but blue-tinted.[8][9] The latter glaze was produced for just one year, while the two former glazes were used for more than a decade.

With increased interest in the American Arts & Crafts Movement, a matte glaze was needed which could be used over under-glaze decoration (largely floral and scenic). Rookwood introduced a "Vellum" glaze in 1904,[10] which presented a matte surface through which the slightly frosted-appearing decoration beneath could be seen.

One of the last glaze lines of Rookwood was "Ombroso," not used until after 1910. Ombroso, used on cut or incised pottery, is a brown or black matte glaze.

In 1902, Rookwood began producing architectural pottery. Under the direction of William Watts Taylor, this division rapidly gained national and international acclaim.[11] Many flat pieces were used around fireplaces in homes in Cincinnati and surrounding areas, while custom installations found their places in grand homes, hotels, and public spaces. Original Rookwood-installed tiles can be viewed in Carew Tower, Union Terminal and Dixie Terminal in Cincinnati,[12] as well as the Rathskeller Room at the Seelbach Hilton in Louisville, Kentucky. In New York City, the Vanderbilt Hotel, Grand Central Station, Lord & Taylor, and several subway stops feature Rookwood tiles. "One of the most important Rookwood tile installations in the country"[13] is on display at the Carnegie West Branch of Cleveland Public Library and depicts Durham Cathedral in England.

The 1920s were highly prosperous years for Rookwood. The pottery employed about 200 workers, including sculptor Louise Abel and future sculptor Erwin Frey,[14] and received almost 5,000 visitors to the Mount Adams business each year.

-

Vase with bat and spiders, 1882

-

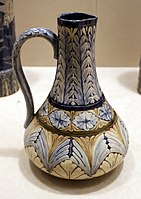

Jug by Abby Hyde Allen for Rookwood, 1883

-

Vase by Albert Robert Valentien, 1893, earthenware with mahogany glaze line

-

Vase by Kataro Shirayamadani, 1901

-

Vase, 1902

-

Fireplace by John D. Wareham, 1903

-

Vase, shape #2000, 1912

-

Angels by Louise Abel, c. 1920, architectural faience

-

Panel of Rookwood tiles of Durham Cathedral

-

The original buildings in 2011, seen from Holy Cross Monastery

Decline

The company was hit hard by the Great Depression. Art pottery became a low priority, and architects could no longer afford Rookwood tiles and mantels.[15][16] By 1934, Rookwood showed its first loss, and by 1936 the company was operating an average of just one week a month. Several employees, most notably Harold Bopp, William Hentschel and David Seyler left the company and started Kenton Hills Porcelains in Erlanger, Kentucky. On April 17, 1941, Rookwood filed for bankruptcy. Through these tough times, ownership of the company changed hands, but the Rookwood artists remained.

In 1959, Rookwood was purchased by the Herschede Clock Company, and production moved to Starkville, Mississippi.[17] Unable to recover from the losses experienced during the Great Depression, production ceased in 1967.[18]

Revival

By 1982, Rookwood was in negotiations to be sold to overseas manufacturers. Michigan dentist and art pottery collector Arthur Townley used his life savings to purchase all of the remaining Rookwood assets. During his tenure as Rookwood's owner, Townley produced small quantities of pieces to maintain the original trademarks. Townley refused offers to sell Rookwood for over two decades, but eventually collaborated with Cincinnati investors Christopher & Patrick Rose in 2004 to move the company back to Cincinnati.[19] In July 2006, after approximately one year of negotiations, the Rookwood Pottery Company entered into a contract to acquire all of the remaining assets of the original Rookwood Pottery from Townley. These assets included, among other things, the trademarks, more than 2,000 original molds, and hundreds of glaze recipes used by the original Rookwood Pottery Company.[20]

In 2011, Martin and Marilyn Wade gained sole ownership of the company.[21] It operates from a production studio in the historic Over-the-Rhine neighborhood of Cincinnati.[22] The company is in full production, having invested in new kilns and equipment and hired new staff.[23] Rookwood Pottery also works with many major institutions to create awards and commemorative pieces. Rookwood Pottery artist Roy Robinson, for example, designed the Center Court Rookwood Cup for the ATP World Tour.[24]

In 2012, the historic Monroe Building of Chicago completed a restoration of its original architectural elements to include the reconditioning and replacement of thousands of original Rookwood Pottery tiles.[25] In 2013, a fireplace created by Rookwood Pottery, in collaboration with artists at the University of Cincinnati, was installed at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati.[26] Describing the collaboration, co-owner Marilyn Wade said: “Our goal in working with these three talented artists is to reposition Rookwood Pottery to what it was originally – a forward-thinking company with its eye on the future, willing to take risks, and in the vanguard of the industry, by affiliating ourselves with like-minded artists.” That same year, Rookwood Pottery was featured on the Martha Stewart Living Blog[27] and on the Science Channel program How It's Made.[28]

In 2017, Rookwood Pottery Company and the Cincinnati Zoo teamed up to create a Fiona ornament, dedicated to a premature hippo.[29]

A dedicated gallery of Rookwood Pottery is in the Cincinnati Wing of the Cincinnati Art Museum.[30]

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ Clark, S. J. (1912). Cincinnati, the Queen City, 1788–1912. Vol. 2. The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company. p. 458.

- ^ a b Zipf, Catherine W. Professional Pursuits: Women and the American Arts and Crafts Movement. University of Tennessee Press, 2007.

- ^ Faithfull, Emily (1884). Three Visits to America. New York: Fowler & Wells Co., Publishers. p. 28.

- ^ "Fry, Laura A. (1857–1943)". Purdue University Libraries, Archives and Special Collections.

- ^ Andrew R. L. Cayton; Richard Sisson; Chris Zacher, eds. (8 November 2006). The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia. Indiana University Press/Ohio State University. p. 568. ISBN 978-0-253-34886-9.

- ^ Fowler, Elizabeth, "'Beware possible intrigues against Gold Award': Rookwood Pottery at the 1889 Exposition Universelle", in Petra ten-Doesschate Chu and Laurinda S. Dixon, eds. Twenty-First-Century Perspectives on Nineteenth-Century Art: Essays in Honor of Gabriel P. Weisberg, 2008:23-28.

- ^ Noah Fleisher (2014). Mary Sieber (ed.). Warman's Antiques & Collectibles 2016 Price Guide. F+W. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-4402-4384-4.

- ^ Noah Fleisher, ed. (2014). Warman's Antiques & Collectibles 2014 (47th ed.). F+W. ISBN 978-1-4402-3462-0.

- ^ Jane Alexiadis (October 19, 2017). "What's It Worth?: Mint-condition Rookwood vase from the 1940s". The Mercury News. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ Eric Bradley, ed. (2012). Antique Trader Antiques & Collectibles Price Guide 2013. Krause Publications. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-4402-3206-0. ISSN 1536-2884.

- ^ Zimmeth, Khristi S. (June 1, 2006). Insiders' Guide Fun With the Family Ohio: Hundreds of Ideas For Day Trips With The Kids. Globe Pequot. p. 134.

- ^ Mohr, Richard, Hogwarts in Cleveland: A Visit to the Carnegie West Branch's Rookwood Fireplace (PDF), retrieved 14 February 2019

- ^ Adams, Philip R., The Sculpture of Erwin F. Frey, The Ohio State University Press, Columbus, 1939 p. 3.

- ^ Zac Bissonnette (2012). Warman's Antiques & Collectibles 2013 Price Guide (46th ed.). F+W. ISBN 978-1-4402-2943-5.

- ^ Eric Bradley, ed. (2017). Antique Trader Antiques and Collectibles Price Guide 2018 (34th ed.). F+W. ISBN 978-1-4402-4840-5. ISSN 1536-2884.

- ^ Mark Chervenka (2007). Antique Trader Guide To Fakes & Reproductions (4th ed.). ISBN 978-0-89689-460-0. LCCN 2006935564.

- ^ Debbie Nunley; Karen Jane Elliott (2007). A Taste of Ohio History: A Guide to Historic Eateries and Their Recipes. John F. Blair. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-89587-341-5.

- ^ Eric Bradley, ed. (2016). Antique Trader Antiques and Collectibles Price Guide 2017 (33rd ed.). F+W. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-4402-4697-5. ISSN 1536-2884.

- ^ Patricia Poore, ed. (Spring 2007). Arts & Crafts Homes and the Revival. William J. O'Donell.

- ^ Benson, Lisa (April 26, 2013). "Restoring Rookwood Pottery". www.bizjournals.com.

- ^ The new studio is at 39°07′02″N 84°31′07″W / 39.11736°N 84.51849°W.

- ^ Laura Baverman, “Rookwood Out of the Fire,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 12, 2011.

- ^ "Rookwood Pottery crafting new trophy for Western & Southern Open". Cincinnati Business Courier. August 6, 2012.

- ^ "Rookwood Pottery Co. Recognized for its Role in the Historic Renovation of Chicago's Landmark Monroe Building". Chicago Business Journal (3). June 30, 2012.

- ^ “The Living Room,” Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati,” contemporaryartscenter.org/Living_Room

- ^ Tom Demeropolis (March 27, 2013). "Rookwood Pottery Featured on Martha Stewart Living Blog". Cincinnati Business Courier.

- ^ John Kiesewetter, “How It's Made to Feature Rookwood Pottery,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 1, 2013.

- ^ Gabi Warwick (October 17, 2017). "Bring a little #TeamFiona bling to your decorations". WKEF. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ "The 10-minute tour". The Cincinnati Enquirer. May 23, 2003. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

External links

- Official website

- Rookwood Pottery Information

- "Where Rookwood Pottery is Made", National Magazine, October 1905 (with photos)