Shingwedzi

Shingwedzi (also Xingwedzi in modern Tsonga orthography[1]) is a rest camp (i.e. tourist camp) and ranger's post situated in the northern section of the Kruger National Park. The camp is located on the southern bank of the Shingwedzi River, for which it is named,[1] in Limpopo province, South Africa. The surrounding country formerly constituted the Singwitsi Reserve, proclaimed in 1903, which encompassed over 5,000 square kilometers.[2] The region was over-hunted by the end of the 19th century, its big game depleted and its elephant population completely decimated.[3] The name "Shingwedzi" is of Tsonga origin, and was perhaps derived from "Shing-xa-goli", perhaps a local chieftain, and "njwetse", the sound of iron rubbing against iron.[4]

History[edit]

During the 19th century the area had only a small native population,[5] as the presence of predators and tsetse fly prevented cattle husbandry. To the immediate east Soshangane established himself as overlord of the lower Bileni/Limpopo valley from 1827/28 to 1835,[6] displacing resident Tsonga people in clashes like the Battle of Xihaheni, while moving northwards.

The rinderpest epidemic of 1896 however ravaged the region's buffalo population, and with it the tsetse fly, the vector of nagana or sleeping sickness.[7] Some now looked at the region for its economic prospects. By the end of the 19th century this remote northeastern part of South Africa was the abode of poachers, illegal loggers, illegal prospectors and illegal recruiters of black labour from across the border.[8]

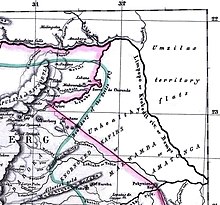

In December 1902, Leonard Ledeboer, a Zoutpansberg resident who had switched sides during the war, suggested the establishment of a reserve to sir Godfrey Lagden of the Department of Native Affairs.[7] The Administrative Proclamation No. 19 of May 1903 which established the Singwitsi Reserve, also brought an end to the lawless exploitation of the region. The reserve boundary went from the Groot and Klein Letaba confluence in a straight line north to Shikumdu Hill, turning northeastwards to the Levuvhu and Crook's Corner. From the Limpopo it ran south along the Portuguese border to the Olifants, and west along the Letaba to the aforementioned confluence.[9] The remote and beautiful reserve could boast with hills topped by baobab trees, the dramatic Lanner and Olifants gorges, lush riparian vegetation, plains with impressive mopane trees, and flood plains adorned with ilala palms and fever trees.[5]

First rangers[edit]

Major James Stevenson-Hamilton was warden of the Sabi (since 1902) as well as Singwitsi Reserves. During his inspection tour of Singwitsi during September and October 1903, Stevenson-Hamilton found that game was scarce. He was nevertheless delighted with the region and found it 'well worth protecting'.[7] Besides the relics of hunting camps[2] there were numerous small African homesteads, the occupants of which subsisted on trapping and hunting by bow and arrow.[3] The scarcity of game he however attributed to systematic hunting by Boer hunters, who were in his opinion doing more damage in a week than the Africans in a year. They had apparently exterminated all the elephant, rhino and eland during the war, and regarded game laws and ordinances as "waste paper", while having "no sporting instincts and no sense of honour as a rule".[3]

From 1904 to 1919 major A. A. Fraser was his only ranger in Singwitsi.[8] The eccentric, red-bearded Fraser was recruited from Scotland as ranger for the small Pongola Reserve (dissolved in 1921),[7] before he was transferred to Malunzane (also Malundzane) in Singwitsi. This deserted base of a former labour recruiter became Fraser's ranger post. It consisted of five rondavels on the bank of the Shongololo stream, not far from the present Mopani rest camp. Fraser was a poor administrator however, considering office work 'undignified', and was besides a poor manager of his native staff. He also developed poor relations with government officials of the district.[7] An additional ranger, J. J. Coetsee, arrived in 1919 from East Africa.[1] He established his ranger's post at the foot of Dimbo Kop in the far north. This he named Punda Maria, perhaps a playful corruption of phande mariha (or "border of the winter"), the alleged Venda appellation for this region.[10] When Stevenson-Hamilton returned from Sudan to South Africa in 1920, he observed that a depressing retrogression had occurred in terms of discipline, management and faunal preservation in both the Sabi and Singwitsi Reserves.[7]

Merged with Sabi Reserve[edit]

In expectation of a government buyout of the land in these reserves, the Singwitsi and Sabi became the Transvaal Game Reserve in 1923, then still privately owned to a large extent. Deneys Reitz, Minister of Lands from 1921 to 1924, and his successor Piet Grobler, advocated the fulfillment of 'Paul Kruger's dream', and the Kruger National Park was established in 1926.[7] The persons involved in the Kruger Park's creation, the extent of their contributions and their political motives are matters of debate, but may be seen as the culmination of various protectionist movements and many strands of thought.[7] By 1932 a good dirt road linked Letaba, Shingwedzi and Punda Maria for the first time, but this road was only accessible to tourists during the winter months.[7]

Camp facilities[edit]

Shingwedzi campsite was established late in 1933, when Bert Tomlinson was the local ranger.[11] The first three of an eventual 31 tourist huts were completed in 1935, but these were only enclosed by a fence much later.[12] Construction of Punda Maria's tourist huts was likewise undertaken during the same time. On 1 April 1977 the tar road from the south reached the camp, which subsequently remained open all year round.[13] During a third development phase, a new administrative complex was added in 1982/3, then outside the camp. The A-circle huts were upgraded to bungalows with bathroom and kitchen facilities, and a guest house was established on the river front. Since 1993 the camp is connected to the main electricity grid,[13] and current accommodation consists of 66 bungalows, 12 huts, 1 family cottage and 1 guest house, besides 50 camping sites. A landing strip is situated just south of the camp.

The Kanniedood Dam was constructed 9km downstream of the camp in 1978, but was demolished 40 years later, in 2018, in line with a rehabilitation project which aims to limit artificial water points for animals.[14] The artificial supply of water in a naturally dry region caused erosion and environmental degradation. Rare herbivore species such as roan suffered due to increased grazing competition by abundant grazers,[14] and from predation by lions which likewise expanded their territories.

Hiking trail[edit]

The Mphongolo Backpack Trail starts from Shingwedzi Camp, but doesn't follow a specific route. It enables small groups of visitors to explore areas like the Mphongolo River, Bububu River, Phonda Hills, sodic pans or stone-walled ruins.[15] The name of the river, Mphongolo, commemorates a former Venda chief, Mapongole.[16]

Rains and floods[edit]

Rainfall is almost entirely restricted to the summer months (October to April),[17] and normally amounts to about 500 mm per annum. The Shingwedzi River flows only during summer, and diminishes to shrinking pools in winter.[4] Heavy rains are normal at the start of each year, which may affect tourist roads, bridges, picnic spots and bush camps. On 24 February 2000 the Shingwedzi River reached record levels when cyclone Leon–Eline struck the northern lowveld. These levels were surpassed on 20 January 2013 when Shingwedzi and Sirheni camps were completely submerged by flood water[18] after 400 mm of rain in a week caused the Mphongolo and Shingwidzi Rivers to burst their banks.[19] 262 people were evacuated on the 20th and airlifted to safety the next day. Some staff were trapped as roads became submerged and survived by taking shelter in trees or on roofs. Some staff and tourists lost all their belongings, and the cost of rebuilding was over R150 million.[19] The camp was reopened for tourists in June 2013.[20]

Fauna and flora[edit]

The camp is situated in elephant country, and breeding herds of 50 to 60 animals frequent the vicinity. The tusks of a local elephant bull named "Shingwedzi" are now displayed in the museum at Letaba. Shingwedzi died in 1981 near the camp, and was one of the so-called "magnificent seven" that roamed the park during the 1970s and 80s.[4] Other Afrotheria which are sparsely resident include the aardvark, Petrodromus, two Elephantulus species and the golden mole. Two species of hyrax are allopatrically distributed, namely the yellow-spotted hyrax which occurs commonly along the northern bush-clad hills and sandstone outcrops, and the rock hyrax, which occurs patchily southwards of the Bubube and Shingwedzi Rivers, but no further south than the Olifants.[22] Ranger D. Swart reported seeing a group of six bat-eared foxes near Shingwedzi in 1967, a species previously thought to be restricted to the western parts of southern Africa. Further sightings in 1967 and 1969 confirmed their presence.[23]

The affinities of the region's avifauna is mainly with the tropical north. Sight records for red-necked spurfowl have been claimed from along the Shingwedzi and Mphongolo rivers, suggesting an isolated population.[17] Two bird species represent the southwesterly arid fauna however, namely the fawn-coloured lark and Kalahari scrub robin, which both occur in the elevated sandveld around Machai Pan.[17] The shaft-tailed whydah likewise occurs there, but not exclusively. Yellow-billed oxpeckers were extinct in the region by 1897, but made an unaided comeback since 1979[24] and are now well-established.[25]

The immediate vicinity of Shingwedzi camp contains some riparian vegetation with large trees, and narrow alluvial plains created by centuries of flooding, flank the river on each side. Here Transvaal mustard trees, weeping boer-bean, sausage tree, Natal mahogany and brack thorn may be found, but further afield the land is dominated by mopane shrub, punctuated by apple-leaf trees.[26] The leafy, large-canopied nyala tree occurs sparsely along the alluvial strips,[16] but more commonly at Pafuri.[27] A nyala tree beside the Mphongolo Loop (S56) road has been assigned champion tree status, in addition to a sycamore fig near Phalaborwa Gate.

Anthrax, caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis, is endemic to the area, and causes sporadic outbreaks.[28] It affects mainly ungulates, but also carnivores and humans. As anthrax inhibits blood clotting, the blood of deceased animals seep into the soil. The spores survive for decades in substrates with elevated calcium content or neutral-to-alkaline pH levels.[28]

Land claim[edit]

In 1905 chief Sundhuza Mhinga and his Mhinga clan were dispossessed of their land in this area, and moved to land west of the park. In 1999 chief Shilungwa Mhinga claimed all land in the park north of the Shingwedzi River, and intended to use the southern portion for ecotourism hotels and other parts for lodges. Land restitution legislation however assists only those dispossessed since 1913, so as to avoid conflicting claims.[29]

Gallery[edit]

-

Yellow-billed stork and crocodiles patrolling the flooded causeway

-

Elephants on the sandy river bed

-

Preserved tusks of "Shingwedzi" (c.1934–1981) at the museum in Letaba camp

-

Real fan palm at the southern limit of its range

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Jenkins, Elwyn (2007). Falling Into Place: The Story of Modern South African Place Names. New Africa Books. pp. 97–100. ISBN 9780864866899.

- ^ a b "The Kruger National Park". The Transvaal (A Collection of the Mobil Treasury of Travel Series covering the Transvaal). Cape Town: T. V. Bulpin. 1975. ISBN 0-949956-12-0.

- ^ a b c Dlamini (12 May 2011). "Kruger Park's future lies with its neighbours". Business Day. Retrieved 6 August 2018 – via PressReader.

- ^ a b c "Shingwedzi Rest Camp - Kruger National Park, South Africa". Siyabona Africa. krugerpark.co.za. 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ a b Fleminger, David. "1903 The Shingwedzi Reserve in Kruger Park". southafrica.co.za. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ Omer-Cooper (1966:57), Elkiss (1981:62)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Carruthers, Jane (1995). The Kruger National Park: A Social and Political History (PDF). Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press. pp. 30–50.

- ^ a b Stevens, Joep (11 December 2014). "Kruger History: A history of Punda Maria and vicinity". krugerhistory.com. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ Stevens, Joep (5 December 2014). "Kruger History: General History". krugerhistory.com. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ Jenkins, Elwyn (2007). Falling into place : the story of modern South African place names. New Africa Books. p. 101. ISBN 9780864866899.

- ^ Stevens, Joep. "Shingwedzi Camp - then and now". Kruger National Park History. facebook. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ "Game Drive around Shingwedzi". Siyabona Africa: Kruger National Park. krugerpark.co.za. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ a b Stevens, Joep (5 February 2023). "Shingwedzi development: phase III". Kruger National Park History. facebook. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ a b Zietsman, Gabi (2018-04-04). "SANParks will demolish Kanniedood dam in Kruger for the environment". traveller24.com. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ Desmet, Andrew; et al. "Mphongolo Backpack trail Explore Krugers northern wilderness areas". krugerpark.co.za. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ a b van der Wateren, Floors (April 2018). Pocket Guide to the Placenames of the Kruger National Park. J Taylor Pre-Print Solutions. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-620-79560-9. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Kemp, A. C. (1 January 1974). The Distribution and Status of the Birds of the Kruger National Park - Koedoe Monograph No. 2 (1 ed.). The National Parks Board of Trustees. p. 2-6, 31.

- ^ "Kruger's Shingwedzi reopens after floods". No. news24.com. City Press. 13 June 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ a b Barry, Hanna (December 2013). "Rebuilding Shingwedzi: how insurance saved SANParks" (PDF). emeraldsa.co.za. REDRiskSA. Retrieved 6 August 2018. [dead link]

- ^ "Shingwedzi re-opens camp following devastating flood". showme.co.za. The Write News Agency, Nelspruit News. 13 June 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Parslow, Ben A.; Schwarz, Michael P.; Stevens, Mark I. (3 August 2020). "Review of the biology and host associations of the wasp genus Gasteruption (Evanioidea: Gasteruptiidae)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 189 (4): 1105–1122. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa005. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Pienaar, U. de V.; Rautenbach, I. L.; de Graaff, G. (1980). The Small Mammals of the Kruger National Park. Pretoria: National Parks Board of South Africa. pp. 11–15, 22–25, 105–110. ISBN 0-86953-018-6.

- ^ Pienaar, U. de V. (1970). "A note on the occurrence of Bat-eared fox Otocyon megalotis (Desmarest) in the Kruger National Park". Koedoe. 13 (1): 1–22. doi:10.4102/koedoe.v13i1.727.

- ^ "Yellow-billed Oxpecker Research - Kruger National Park". Facebook. @KNPoxpeckers · Community. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Kruger's yellow-billed oxpeckers in focus". Wild Card. wildcard.co.za. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Shingwedzi Rest Camp: Flora and Fauna". sanparks.org. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ van Wyk, Piet (1984). Field Guide to the Trees of the Kruger National Park. Cape Town: Struik. p. 98. ISBN 0-86977-221-X.

- ^ a b Steenkamp, P. J. "Ecological suitability modelling for anthrax in the Kruger National Park, South Africa". repository.up.ac.za. University of Pretoria. hdl:2263/23358. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ ka’Nkosi, Sechaba (29 Jan 1999). "Two clans claim part of the Kruger". Mail&Guardian. Retrieved 13 November 2018.