Sleepers (film)

| Sleepers | |

|---|---|

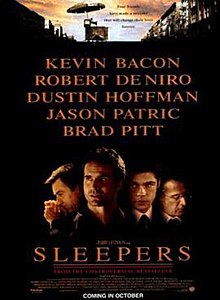

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Barry Levinson |

| Screenplay by | Barry Levinson |

| Based on | Sleepers by Lorenzo Carcaterra |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus |

| Edited by | Stu Linder |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. (North America) PolyGram Filmed Entertainment[1][2] (International) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 147 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $44 million[3] |

| Box office | $165.6 million[4] |

Sleepers is a 1996 American legal crime drama film written, produced and directed by Barry Levinson, and based on Lorenzo Carcaterra's 1995 book of the same name. The film stars Kevin Bacon, Jason Patric, Brad Pitt, Robert De Niro, Dustin Hoffman, Minnie Driver, Vittorio Gassman, Brad Renfro, Ron Eldard, Jeffrey Donovan, Terry Kinney, Joe Perrino, Geoffrey Wigdor, Jonathan Tucker, Bruno Kirby and Billy Crudup. The title is a slang term for juvenile delinquents who serve sentences longer than nine months.[5]

Sleepers was theatrically released in the United States October 18, 1996, and was a box-office hit, grossing $165.6 million against a $44 million budget.

Plot[edit]

Lorenzo "Shakes" Carcaterra, Tommy Marcano, Michael Sullivan and John Reilly are childhood friends living in Hell's Kitchen in the 1960s. Father "Bobby" Carillo, their parish priest, a youth offender himself in the past, tries to teach them right from wrong. They still play pranks and start running small errands for local gangster King Benny.

In summer 1967, the four boys steal a hot-dog cart. They accidentally roll the cart down a set of subway stairs, severely injuring a man. They are all sentenced to serve time at a juvenile detention center called Wilkinson Home for Boys in Upstate New York; Shakes is given six-to-twelve months, while the others are given 12-to-18 months. During their stay, they are repeatedly subjected to sexual abuse and torture by head guards Sean Nokes, Henry Addison, Ralph Ferguson and Adam Styler.

When at the facility, they participate in Wilkinson's annual football game between the guards and inmates. Michael convinces inmate Rizzo Robinson to help win the game. Humiliated, the guards move the boys to solitary confinement for weeks, where they are systematically beaten. Rizzo does not survive, and his family is told he had died of pneumonia.

In spring 1968, shortly before Shakes's release from Wilkinson, he suggests the boys publicly report the abuse. The others refuse, with Michael asserting that no one would believe them or care, and they vow to never speak of it again. The night before Shakes is released, Nokes and the other guards arrange a "farewell party", in which the four boys are brutally raped worse than they have been before.

In 1981, John and Tommy, now career criminals working with the Irish Mob, unexpectedly encounter Sean Nokes in a Hell's Kitchen pub. When John and Tommy confront him, he dismisses the abuse he put them through, and they fatally shoot him in front of witnesses. Michael, now an assistant district attorney, gets himself assigned to the case; he secretly intends to botch the prosecution to expose the abuse committed by the guards at Wilkinson's. With Shakes, now a timetable clerk for the New York Times, he forms a plan to free John and Tommy to get revenge on the other Wilkinson abusers. With the help of King Benny and Carol, the boys' childhood friend, they carry out their plan using information compiled by Michael on the backgrounds of the guards. They are helped by Danny Snyder, an alcoholic lawyer who defends John and Tommy.

Michael secretly drafts scripted questions for Snyder in advance. As a result, Snyder casts significant doubt on the testimony of a woman who witnessed the murder, and two other witnesses are intimidated into silence. For his plan to fully succeed, however, Michael decides that he must damage Nokes's reputation and convincingly place John and Tommy at another location at the time of the shooting. When called as a witness, Ferguson (now a social worker) admits that Nokes and the other guards systematically abused the boys. But to clinch the case, a key witness is still needed for John and Tommy's alibi. Shakes has a long talk with Father Bobby; after learning the truth about the abuse the boys suffered, he reluctantly agrees to perjure himself, and testifies at trial that John and Tommy were with him at a New York Knicks game at the time of the shooting, producing three ticket stubs to prove it. As a result, John and Tommy are acquitted.

The remaining guards are also punished for their crimes: Addison, now a politician who still molests children, is abducted and killed near the local airport by gangsters led by Rizzo's older brother, Eddie "Little Caesar" Robinson, who heard the truth about Rizzo's death from King Benny. Styler, now a corrupt police officer, is imprisoned for taking bribes and murdering a drug dealer; and Ferguson loses his job and family, and spends the rest of his life working menial jobs and wracked with guilt.

After the acquittal, Michael, Shakes, John and Tommy meet with Carol at a local bar to celebrate. It is the final time the four men are together. Shakes remains in Hell's Kitchen and working at the newspaper. Michael quits the DA's office, moves to the English countryside, becomes a carpenter and never marries. John and Tommy both die before age 30; John succumbs to alcohol poisoning, while Tommy is ambushed and murdered by rival criminals. Carol remains in Hell's Kitchen as a social worker; she has a son, naming him John Thomas Michael Martinez, and nicknaming him "Shakes".

Cast[edit]

- Billy Crudup as Thomas “Tommy” Marcano

- Jonathan Tucker as Young Tommy Marcano

- Ron Eldard as John Riley

- Geoffrey Wigdor as Young John Riley

- Jason Patric as Lorenzo 'Shakes' Carcaterra

- Joe Perrino as Young Shakes

- Brad Pitt as Michael Sullivan

- Brad Renfro as Young Michael Sullivan

- Kevin Bacon as Sean Nokes

- Robert De Niro as Father Robert “Bobby” Carillo

- Minnie Driver as Carol Martinez

- Monica Polito as Young Carol Martinez

- Vittorio Gassman as Benny 'King Benny'

- Sean Patrick Reilly as Young 'King Benny'

- Dustin Hoffman as Danny Snyder

- Terry Kinney as Ralph Ferguson

- Peter McRobbie as lawyer

- Bruno Kirby as Shakes' father

- Frank Medrano as 'Fat' Mancho

- Eugene Byrd as Rizzo Robinson

- Jeffrey Donovan as Henry Addison

- Wendell Pierce as Eddie 'Little Caesar' Robinson

- Lennie Loftin as Adam Styler

- Aida Turturro as Mrs. Salinas

- Dash Mihok as K.C.

- Angela Rago as Shakes' mother

- John Slattery as Mr. Carlson

- James Pickens Jr. as Guard Marlboro

- George Georgiadis as Hot Dog Vendor

Production[edit]

Lorenzo Carcaterra first submitted a manuscript of his book Sleepers, to Ballantine Books, which immediately attracted interest from multiple film companies. Ultimately, Propaganda Films managed to obtain the movie rights for $2.1 million at an auction in February 1995. Barry Levinson was attached as director mere days afterward, and opted to write the screenplay himself.[6]

The first words spoken in the film are: "This is a true story about friendship that runs deeper than blood".[7][8] However, the truthfulness and factual accuracy of the film — and the book on which it is based — were challenged by the Sacred Heart of Jesus Church and School in Manhattan (the school attended by Carcaterra), and by the Manhattan District Attorney's office, among others.[7][8] Carcaterra has acknowledged that most details in the book were fictionalized, but maintained that the events described in the book actually occurred.[8][9] Brad Pitt was cast alongside Robert de Niro in July 1995, and filming began the following month. In response to the fast pace of the production process, Ballantine scheduled the book to be released around the same time that de Niro and Pitt were cast.[6]

Emilio Estevez was cast as John Riley, but was already involved in three movies that year; Sandra Bullock was cast as Carol, but was already involved in the movie A Time to Kill, and was thus replaced by Minnie Driver.

As they had previously worked together on Diner, Kevin Bacon was approached by Levinson to play the role of Nokes, but did not read the book until after he accepted the role. Due to the logistics of filming, Bacon did not meet de Niro or Dustin Hoffman until the film's premiere in Venice.[10]

Release[edit]

Box office[edit]

In its opening weekend, the film grossed $12.3 million from 1,915 theaters in the United States and Canada, debuting atop of the box office. Sleepers grossed $53.3 million domestically and $112.3 million internationally, for a worldwide total of $165.6 million.[4]

Critical response[edit]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 73%, based on 56 reviews, with an average rating of 6.60/10. The site's critics consensus reads: "Old friendships are awakened by the need for revenge, making Sleepers a haunting nightmare burdened by voiceover yet terrifically captured by Barry Levinson."[11] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 49 out of 100, based on 18 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[12] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A–" on a scale of A+ to F.[13]

Critics praised the performances of De Niro, Hoffman, Bacon and the young cast,[14] as well as the cinematography and production design.[14][7] However, multiple critics said the film loses focus in its second half.[15][16][17] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly wrote, "Sleepers wants to do something impossible — merge the mournful, drenched-in-shame emotions of child abuse with the huckster gamesmanship of a contraption like The Sting."[18]

David Ansen of Newsweek criticized Levinson's script, and reasoned the adult characters of Shakes, Michael, John and Tommy were not fully fleshed out.[17]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times awarded the film three stars of four, but said it did not engage enough in the moral issues it purported to be about.[7]

Steve Davis of The Austin Chronicle wrote, "What a more interesting film this would have been had Levinson found a way to integrate the past and the present so that one informed the other."[19]

When the film was released, there was controversy about how much of the novel claimed to be a true story, and how much had been invented by its author.[8]

Accolades[edit]

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Original Dramatic Score | John Williams | Nominated | [20] |

| London Film Critics Circle Awards | British Supporting Actress of the Year | Minnie Driver[a] | Won | [21] |

| Young Artist Awards | Best Performance in a Feature Film – Leading Young Actor | Joe Perrino | Nominated | [22] |

| Best Performance in a Feature Film – Supporting Young Actor | Geoffrey Wigdor | Nominated | ||

| YoungStar Awards | Best Performance by a Young Actor in a Drama Film | Joe Perrino | Nominated | [23] |

| Brad Renfro | Nominated |

Home media[edit]

The film was released on VHS by Warner Home Video on April 1, 1997. The film was released on DVD August 18, 1997, and on Blu-ray August 2, 2011.[24]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Also for Big Night and Grosse Pointe Blank.

References[edit]

- ^ "Sleepers (35mm)". Australian Classification Board. 30 August 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Sleepers (18)". British Board of Film Classification. 21 October 1996. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Sleepers (1996) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC.

- ^ a b "Sleepers (1996)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Streitfeld, David (26 July 1995). "Sleepers': A Rude Awakening?". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ a b Cardozo, Erica (14 July 1995). "Sleepers begins shooting film version". EW.com. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d Ebert, Roger (18 October 1996). "Sleepers movie review & film summary (1996)". Chicago Sun-Times – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ a b c d Weinraub, Bernard (22 October 1996). "'Sleepers' Debate Renewed: How True Is a 'True Story'?". The New York Times.

- ^ Hampson, Rick (31 July 1995). "'Sleepers': Nonfiction Without the Facts". Associated Press News.

- ^ Adamek, Pauline. "Kevin Bacon talks about "Sleepers" and that game named after him". Arts Beat LA. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ Sleepers at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Sleepers at Metacritic

- ^ "Sleepers". CinemaScore (search "sleepers"). Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ a b Maslin, Janet (18 October 1996). "Artificiality Vanquishes An Authenticity Issue". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Stack, Peter (18 October 1996). "FILM REVIEW -- 'Sleepers' Guaranteed to Keep Audiences Awake". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (18 October 1996). "A Graphic Tale of Revenge". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ a b Ansen, David (27 October 1996). "Vigilante Chic Is Back". Newsweek. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (1 November 1996). "Sleepers". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Davis, Steve (25 October 1996). "Movie Review: Sleepers". Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ "The 69th Academy Awards | 1997". Academy Awards. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ "Sleepers - Awards & Festivals". MUBI. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ "18th Annual Youth in Film Awards". YoungArtistAwards.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ "1997's 2nd Annual Young Star Awards". allyourtv.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Sleepers Blu-ray". blu-ray.com. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

External links[edit]

- Sleepers at IMDb

- Sleepers at Box Office Mojo

- Sleepers at Rotten Tomatoes

- Sleepers at Metacritic

- 1996 films

- 1990s American films

- 1996 crime drama films

- American coming-of-age films

- American courtroom films

- American crime drama films

- American buddy drama films

- American prison drama films

- 1990s buddy drama films

- 1990s English-language films

- Films about child sexual abuse

- Films about pranks

- Films directed by Barry Levinson

- Films scored by John Williams

- Films produced by Steve Golin

- Films based on American novels

- Films set in 1967

- Films set in 1968

- Films set in 1981

- Films set in New York (state)

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in Connecticut

- Films shot in New York City

- PolyGram Filmed Entertainment films

- American films about revenge

- American rape and revenge films

- Warner Bros. films

- Films about the Irish Mob