The Battle of Waterloo (film)

| The Battle of Waterloo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Charles Weston |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | George Foley |

Release date |

|

Running time | 86 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | Silent |

| Budget | £1,800 |

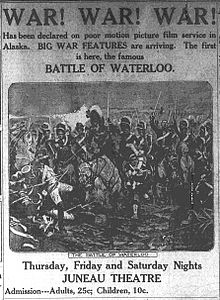

The Battle of Waterloo is a 1913 feature film created by British and Colonial Films to dramatize the eponymous battle ahead of its centenary. The Battle of Waterloo was much longer and more costly than contemporary films but went on to great commercial and critical success. Though the film was shown in theaters around the world, all copies were thought lost until 2002, when about 22 minutes of the hour-and-a-half production were rediscovered at the British Film Institute archives. Since then, two reels and a fragment have been compiled, representing about half the completed film.

Cast

- Ernest G. Batley as Napoleon Bonaparte

- George Foley as Field Marshal Gebhard von Blucher

- Vivian Ross as Marshal Michel Nay

Inspiration

The first two decades after the invention of the film camera were marked by a progression toward larger and more elaborate productions. From short vignettes of a single subject, films evolved to include multiple scenes, locations and actors. In 1910, Barker Motion Photography released Henry VIII, a 30-minute recreation of the Shakespearean play.[1] The success of this movie, (the first lengthy production by a British film studio) and similar foreign productions encouraged British and Colonial Films to produce its own feature film. The company, based in East Finchley, London, had already created several short films and documentaries, but The Battle of Waterloo was its longest production to date.

Production

To direct the film, British and Colonial Films hired American director Charles Weston. To raise money for the production, John Benjamin McDowell, one of the founders of British and Colonial, remortgaged the company for £1,800. Weston chose to film the production in Irthlingborough, Northamptonshire, a place the Duke of Wellington reportedly said reminded him of the terrain around Waterloo, Belgium.[2] Hundreds of local residents were used as extras. Some were paid, while others volunteered. There were so many volunteers that two shoe factories in the town had to close for lack of workers.[2][3] Subsequent advertisements indicated the movie contained 2,000 soldiers, 116 scenes, 1,000 horses and 50 cannons.[4]

'C' Squadron of the 12th Lancers cavalry regiment was loaned to the production from its base at Weedon Barracks. More than 100 horses came from the London stables of Thomas Tilling, which at the time was the biggest supplier of horsepower in London. The regimental historian recorded, "An accommodating American made the rounds of all the pubs at night to pay for drinks. The fact that Napoleon could not ride and that a sergeant in the regiment appropriated Wellington's boots nearly prevented the film being made and 'C' Sqn from taking part in the most exciting, best paid and least painful battle of the regiment's long history."[4]

Despite the complexities of the production, filming was completed in just five days, and the resulting edited film encompassed about 5,000 feet (1,500 m) of film over five reels.[5]

Reception

Commercially, the film returned John Benjamin McDowell's investment many times over. British display rights alone were sold for £5,000, and international display rights earned the company even more.[5] It was the feature shown at the opening of the Alcazar in Edmonton, London.[6] Critically, the film received mixed reviews. Bioscope, a British film journal, praised British and Colonial's effort to preserve a portion of British history with a British production. It tempered this praise by noting that the film recreated scenes from the battle "from the point of view of an ordinary soldier in the thick of the battle," but there was almost no dramatic or human interest.[7]

The film was popular enough that a parody, Pimple's Battle of Waterloo, was hurriedly put into production and released later that year.[8]

After the success of The Battle of Waterloo, British and Colonial continued to produce longer films. After the start of World War I, many of the same filmmakers who produced Waterloo were put to work on propaganda films, the most famous of which is The Battle of the Somme.

The original prints of The Battle of Waterloo were struck on nitrate film and have been lost. Only fragments survive in the British Film Institute's archive. The entire film was thought lost until 2002, when 22 minutes were rediscovered in the archive. Additional fragments have been compiled, the equivalent of about two and a half reels of film.[2]

References

- Turvey, Gerry. "The Battle of Waterloo (1913): The First British Epic," in Burton and Porter (eds) The Showman, the Spectacle and the Two-Minute Silence: Performing British Cinema before 1930. Trobridge: Flicks Books, pp. 40–47.

- '"The Battle of Waterloo": British History Reconstructed by Britons', Bioscope. 3 July 1913, pp. 51.

- 'Our Poster Gallery: "The Battle of Waterloo"', Bioscope, 14 August 1913. pp. 24.

Notes

- ^ Ede, Laurie. British Film Design. I.B. Tauris, 2010. pp. 12

- ^ a b c "Irthlingborough's 'Battle of Waterloo' film celebrated," bbc.com. 7 June 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ^ "The Battle of Waterloo," Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ^ a b Paget, George Charles Henry Victor. A History of British Cavalry: Volume 4, 1899-1913. Pen and Sword, 1993. pp. 486

- ^ a b McKernan, Luke. The Battle of Waterloo: or, Why Can't We Film Such a Thing If We Won the War in the First Place?, 1996. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ^ "Historic buildings: Upper Edmonton" by Stephen Gilburt in Enfield Society News, No. 206 (Summer 2017), pp. 6-7.

- ^ '"The Battle of Waterloo": British History Reconstructed by Britons', Bioscope. 3 July 1913, pp. 51.

- ^ "Pimple's Battle of Waterloo", British Film Institute. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

External links

- 1914 films

- 1913 films

- 1910s historical films

- British films

- British historical films

- British silent feature films

- British epic films

- British black-and-white films

- Films set in Belgium

- Films set in Waterloo

- Works about the Battle of Waterloo

- Cultural depictions of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

- Cultural depictions of Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher

- Depictions of Napoleon on film

- Napoleonic Wars films

- Films set in 1815

- 1910s war drama films

- British war drama films

- War epic films

- 1913 drama films

- 1914 drama films