Ulaanbaatar

Ulan Bator | |

|---|---|

| Official Cyrillic transcription(s) | |

| • Mongolian cyrillic | Улаанбаатар |

| • Transcription | Ulaanbaatar |

| Classical Mongolian transcription(s) | |

| • Mongolian script | ᠤᠯᠠᠭᠠᠨᠪᠠᠭᠠᠲᠤᠷ |

| • Transcription | Ulaγanbaγatur |

Ulan Bator City | |

| Nickname(s): УБ (UB), Нийслэл (capital), Хот (city) | |

| Country | Mongolia |

| Established as Urga ᠥᠭᠦᠭᠡ | 1639 |

| current location | 1778 |

| Ulan Bator | 1924 |

| Government | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,704.4 km2 (1,816.3 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,350 m (4,429 ft) |

| Population (2012-04-30) | |

| • Total | 1,221,000 |

| • Density | 259/km2 (672/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (H) |

| Postal code | 210 xxx |

| Area code | +976 (0)11 |

| License plate | УБ_ (_ variable) |

| ISO 3166-2 | MN-1 |

| Website | www.ulaanbaatar.mn |

Ulan Bator /[invalid input: 'icon']ˌuːlɑːn ˈbɑːtər/, or Ulaanbaatar (Mongolian: Улаанбаатар, [ʊɮɑːŋ.bɑːtʰɑ̆r], ᠤᠯᠠᠭᠠᠨᠪᠠᠭᠠᠲᠤᠷ,Ulaγanbaγatur, literally "Red Hero"), is the capital and the largest city of Mongolia. An independent municipality, the city is not part of any province, and its population as of 2008 is over one million.[1]

Located in north central Mongolia, the city lies at an elevation of about 1,310 metres (4,300 ft) in a valley on the Tuul River. It is the cultural, industrial, and financial heart of the country. It is the centre of Mongolia's road network, and is connected by rail to both the Trans-Siberian Railway in Russia and the Chinese railway system.[2]

The city was founded in 1639 as a movable (nomadic) Buddhist monastic centre. In 1778 it settled permanently at its present location, the junction of the Tuul and Selbe rivers. Before that it changed location twenty-eight times, with each location being chosen ceremonially. In the twentieth century, Ulan Bator grew into a major manufacturing centre.[2]

Names

Ulan Bator has been given numerous names in its history. Before 1911, the official name was Ikh Khüree (Mongolian: Их Хүрээ, "Great Camp") or Daa Khüree (Даа Хүрээ, cf Chinese: 大, dà, "great"), or simply Khüree. Upon independence in 1911, with both the secular government and the Bogd Khan's palace present, the city's name changed to Niĭslel Khüree (Нийслэл Хүрээ, "Capital Camp"). It is called Bogdiin Khuree (Богдийн Хүрээ, Bogdiĭn Khüree, "Saint's Camp") in the folk song "Praise of Bogdiin Khuree". In western languages, the city at that time was most often referred to as Urga (from Mongolian: Өргөө, Örgöö, "Residence").

When the city became the capital of the new Mongolian People's Republic in 1924, its name was changed to Ulan Bator (Улаанбаатар, Ulaanbaatar, classical Mongolian Ulaγanbaγatur, literally "Red Hero"). On the session of the 1st Great People's Khuraldaan of Mongolia in 1924, majority of delegates expressed their wish to change the capital city's name to Baatar[disambiguation needed] Khot (Hero City). However, under the pressure of the Soviet activist of Communist International, Turar Ryskulov, the city was named Ulan Bator Khot (City of Red Hero).[3] No particular name of who was that red hero was quoted in the documents.

In Europe and North America, Ulan Bator generally continued to be known as Urga or sometimes Kuren (or Kulun) till 1924, and Ulan Bator afterwards (a spelling derived from [Улан-Батор] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Ulan-Bator). The Russian spelling is different from the Mongolian because it was defined phonetically, and the Cyrillic script was only introduced in Mongolia seventeen years later. By Mongols, the city was nicknamed Aziĭn Cagaan Dagina (Азийн Цагаан Дагина, "White Fairy [Dakini] of Asia") in the late 20th century.

History

Pre-1778 settlements

Human habitation at the site of Ulan Bator dates from the Lower Paleolithic. Alexey Okladnikov's archeological work in 1949 and 1960 revealed many Paleolithic sites on Mt. Bogd Khan Uul, Buyant-Ukhaa and Mt. Songinokhairkhan. In 1962 various Paleolithic tools were discovered at Mt. Songinokhairkhan as well as Buyant-Ukhaa (23 stone tools) that scholars date from 300.000 years ago to 40.000-12.000 years ago. Okladnikov also revealed an Upper Paleolithic (40.000-12.000 years ago) site on the south-east base of the Zaisan Hill north of Mt. Bogd Khan Uul. Byambyn Rinchen mentions it as an inspiration for his prehistoric novel Zaan Zaluudai. The lower strata of this bistratified settlement located at the present-day Zaisan Memorial revealed tools and materials fashioned according to the Levallois technique. These Upper Paleolithic people hunted mammoth and wooly rhinoceros, the bones of which are found abundantly around Ulan Bator.

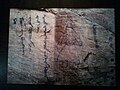

Red ochre rock paintings from the Bronze Age (3000 years ago) are to be found at Ikh Tenger Gorge on the north side of Mt. Bogd Khan Uul facing the city. The paintings show human figures, horses, eagles and abstract designs like horizontal lines and large squares with over a hundred dots within them. The same style of painting from the same era is found very close to the west of the city at Gachuurt, as well as in Khovsgol Aimag and southern Siberia, indicating a common South Siberian nomadic pastoral culture. Mt. Bogd Khan Uul was probably an important religious cult location for these people. Bronze Age square slab tombs are found at the Shajin Khurakh and Tur Khurakh gorges of Mount Bogd Khan Uul facing the city.

To the north of Ulan Bator there are the vast Noin-Ula Xiongnu (Hunnu) royal tombs which are over 2000 years old. A Xiongnu tomb has been found in Chingeltei district. The Xiongnu tombs of Belkh Gorge near Dambadarjaalin monastery are under city protection. The Xiongnu tombs of Mount Songinokhairkhan however are under national protection. Wooden cups, plates, ceramic vessels and a 12 branch deer horn were found in the "Xiongnu Queen Tomb" (Hunnu Khatni Bulsh) at the Baruun Boginiin Am gorge of Mount Bogd Khan Uul. Located on the banks of the sacred Tuul River ("Khatun Tuul" or Queen Tuul in legend), the area of Ulan Bator was well within the sphere of nomadic empires such as the Xiongnu (Hunnu) (209BC-93AD), Xianbei (Sumbe) (93AD-4th century), Rouran (Nirun) (402-555), Göktürk (555-745), Uighur (745-840), Khitan (907-1125) and Mongol Empire (1206–1368). At Nalaikh District there is the important Stele of Tonyukuk (c. 722 AD) with an Old Turkic inscription in the Orkhon alphabet.

A balbal or ancient human statue was chosen as the ceremonial foundation site (Shav) of the city when it settled in 1778 at its current location. Now a modern stone turtle sits atop the spot of the ancient balbal near Sükhbaatar Square in the city center.

Wang Khan Toghrul of the Kerait, a Nestorian Christian monarch who was identified as the legendary Prester John by Marco Polo, is said to have had his palace here (the Black Forest of the Tuul River) and forbade hunting in the holy mountain Bogd Uul. The ruins of his palace (15x27 metres with a gate facing south) was found in Songinokhairkhan District in 1949 and excavated by D.Navaan in 2006. This brick palace influenced by Chinese architecture, later also called the Third Palace of Genghis Khan or Yesui Khatun's palace, is where Genghis Khan stayed with Yesui Khatun before attacking the Tangut. A drainage channel carried roof water out through the east and west gates of the complex. In 2003 Japanese and Koreans made special programs about this palace where many important events of Genghis Khan's life took place. Genghis Khan's father Yesukhei became blood brothers with Toghrul here and later Genghis Khan himself became son of Toghrul at this place.

The Secret History of the Mongols mentions this area in many places, for example in Paragraphs 115 and 264:

(After defeating the Merkits with Temujin and Jamukha)...Toghrul Khan returned home, following the edge of Mount Burkhan Khaldun, going past Ogort Forest, continuing past Gachuurt suvchid and Uliastai suvchid, hunting along the way, till he came to the Black Forest of the Tuul River. (SHM 115)

Genghis Khan...crossing the Indus River chased Jalaldin Sultan and Khan Malik till the land of the Hindu, but they escaped. So he took many border people of the Hindu region captive and came back bringing many camels and goats. From there Genghis Khan returned, spending the summer at the Irtysh River and reaching the Black Forest of the Tuul River in autumn of the Year of the Rooster (1225), where he set up his Ordo (royal camp) and spent the winter. (SHM 264) He rode against the Xi Xia the next year taking Queen Yesui with him.

In 1984 a rich 13th century tomb of a 50-60 year old, 175 cm tall warrior with an ornate golden belt was excavated at Dadart Uul of Mt.Songinokhairkhan. He was buried with a sheep scapula, a dagger with iron blade and wooden handle, a 65cm bark quiver with three iron arrows inside, two light curved stirrups (13th century type) and remains of a cast iron tripod cauldron. His highly ornate belt composed of 39 parts with a scarab at his right hip has led to speculations this is the tomb of Jamukha. A simple 13th century rock painting of a Mongolian woman with distinct Mongolian headdress can be seen on the north side of Mt Bogd Khan Uul. Abtai Sain Khan is said to have worshipped the mountain in the 16th century as well. The French missionary Gerbillon camped at the site of Ulan Bator on August 5, 1698 and continued north the next day along the Selbe River valley (present-day Sukhbaatar District). He says in his Journal:

On the 5th, we made fifty li, which should actually be reduced to thirty-five li (17km), West-North-West, because of a big detour we made in the mountains, holding to the south and south-west to avoid the marshes of the plains. We camped on the banks of the Tula, which separates into many branches, still ornamented by beautiful trees. On the way we passed many streams that empty into the River, and for a distance of about thirty li, we followed the edge of a high mountain, called Han-alin (Mount Bogd Khan Uul), covered by a grand forest of pine and fir trees, full of bears, wild boars and deer. We camped in the valley that is at the foot of this mountain, on the bank of the same River.[4]

The Manchu envoy Toulischen wrote an account of his travels through this region in 1712, describing how his party rested and fished ten to twenty salmon and pike in the river "Tu-la" while one Ko-tcha-eur-too killed a deer with a gun in the "Han-shan" (i.e., Khan Uul). He also describes the "rich and luxuriant" nature around the "Sung-kee-na" mountains (i.e., Mount Songino Khairkhan).[5] Before Khalkha Mongolian nobles went and pledged allegiance to the Manchu emperor at Dolon Nor in 1691, the area of present-day Ulaanbaatar was under the control of Tusheet Khan Chakhundorj the brother of Zanabazar. In 1691 Chakhundorj's eldest son Galdandorj was given the title Jun Wang at Dolon Nor and given the area of present-day Ulaanbaatar. From that time onwards it became a clearly demarcated hereditary princedom called the Darkhan Chin Wangiin Khoshuu (Banner of the Darkhan Chin Wang). The Banner was centered on Mount Bogd Khan Uul and its boundaries are described in historical records of the period.[6] Galdandorj (1691-1692) was the first Darkhan Chin Wang. His successors are: his eldest son Dondovdorj (1692-1743), Rinchendorj (1743-1755), Khajivdorj (1757-1759), Gejeedorj (1759-1771), Tsevdendorj (1771-1774), Sundevdorj (1774-1798), Nyambuudorj (1799-1832) all the way till Darkhan Chin Wang Puntsagtseren (1914-1921). Starting from 1728 till 1921 the 21 banners of Tusheet Khan Aimag held the "Khan Uuliin Chuulgan" (Assembly of Khan Uul) every three years at the north side of Mount Bogd Khan Uul, the site of Ulaanbaatar. The Assembly discussed a wide range of issues including finances, military census, livestock tax and legal issues. There were 26 Presidents of the Khan Uul Assembly starting from Tusheet Khan Vanjildorj (1728-1732) till Puntsagtseren (1914-1921). There were also a total 30 Deputy Presidents or Speakers.[7] The 2nd Jebtsundamba Khutuktu was born at Mount Songinokhairkhan in present-day Ulaanbaatar in 1724 as the son of Darkhan Chin Wang Dondovdorj and Tsagaan Dari Bayart. Dondovdorj carried the titles Jun Wang, Darkhan Chin Wang, Khoshoi Chin Wang and Efu and also sat on the Tusheet Khan throne for two years (1700-1702). He played a part in bringing Urga inside his banner territory. From 1733 to 1743 he was both the Said (Minister-governor) of Urga and the President of the Khan Uul Assembly. One of his wives was Amarlingui Hichiyengui the 6th daughter of the Kangxi Emperor whom he received in marriage in 1697. Her tomb the Gunj Temple (1740) is partially intact in the forests north-east of Ulaanbaatar. Dondovdorj, an accomplished poet, composed the song "Tumen Ekh" praising a race horse[1]. In 1696 Zanabazar and the Khalkha Mongolian nobles returned from Dolon Nor and camped at the north side of Mount Bogd Khan Uul. The gorge where khans and princes camped was called Tur Khurakhyn Am (State Gathering Gorge) while the one where monks and abbots camped was named Shajin Khurakhyn Am (Religion Gathering Gorge). Nobles and lamas continued to meet at this place for the next 330 years. Nukhtiin Am, on the south of Ulan Bator, was where Zanabazar (1635-1723) consecrated and meditated under a tree called Janchivsembe, the shadow of which was used to choose the location of Gandan Monastery in 1838.

-

3000 year old Bronze Age red ochre paintings.

-

Inscribed royal cups from the Xiongnu (Hunnu) tombs just north of Ulan Bator.

-

Chariots of the Xiongnu (Hunnu) (209BC-93AD) were common in the Ulan Bator area.

-

Construction materials from Tereljiin Dorvoljin (209BC-93AD) within the sphere of larger Ulan Bator.

-

Stele of Tonyukuk (722AD) in Nalaikh District, Ulan Bator.

-

Remains of Wang Khan's 12th century palace in Ulan Bator.

-

Remains of Wang Khan's 12th century palace in Ulan Bator.

-

Elephant head from the 13th century ruins of Bukheg Balgas in Ulan Bator.

-

Buddha head from the 13th century ruins of Bukheg Balgas in Ulan Bator.

-

Simple 13th century rock painting of a Mongolian woman in southern Ulan Bator.

Mobile monastery

Founded in 1639 as a yurt monastery, Ulan Bator, then Örgöö (palace-yurt), was first located at Lake Shireet Tsagaan nuur (just east of the imperial capital Karakorum) in what is now Burd sum, Övörkhangai, around 250 km south-west from the present site of Ulan Bator, and was intended by the Mongol nobles to be the seat of the first Jebtsundamba Khutughtu, Zanabazar, son of Tusheet Khan Gombodorj. In 1651 Zanabazar returned to Mongolia from Tibet and founded seven aimags (monastic departments) in Urga. They were the Department of the Treasury, Department of Administration, Department of Meals, Department of the Honored Doctor, Department of Amdo, Department of Orlog and the Department of Khuukhen Noyon. In his old age he established four more monastic departments in Urga.

As a mobile monastery-town, it was often moved to various places along the Selenge, Orkhon and Tuul rivers, as supply and other needs would demand. During the Dzungar wars of the late 17th century, it was even moved to Inner Mongolia.[8] As the city grew, it moved less and less.[9] The movements of the city can be detailed as following: Shireet Tsagaan Nuur (1639), Khoshoo Tsaidam (1640), Khentii Mountains (1654), Ogoomor (1688), Inner Mongolia (1690), Tsetserlegiin Erdene Tolgoi (1700), Daagandel (1719), Usan Seer (1720), Ikh Tamir (1722), Jargalant (1723), Eeven Gol (1724), Khujirtbulan (1729), Burgaltai (1730), Sognogor (1732), Terelj (1733), Uliastai River (1734), Khui Mandal (1736), Khuntsal (1740), Udleg (1742), Ogoomor (1743), Selbe (1747), Uliastai River (1756), Selbe (1762), Khui Mandal (1772), Selbe (1778). In 1778, the city moved from Khui Mandal and settled for good at its current location, near the confluence of the Selbe and Tuul rivers and beneath Bogd Khan Uul, back then also on the caravan route from Beijing to Kyakhta.[10] One of the earliest Western mentions of Urga is the account of the Scottish traveller John Bell in 1721:

What they call the Urga is the court, or the place where the prince (Tusheet Khan) and high priest (Bogd Jebtsundamba Khutugtu) reside, who are always encamped at no great distance from one another. They have several thousand tents about them, which are removed from time to time. The Urga is much frequented by merchants from China and Russia, and other places.[11]

Another early mention is in the Journal of Swedish explorer Lorenz Lange in 1722:

In regard to our commerce with China, it is, at present, in a very languishing condition; and nothing in the world would bring more prejudice to our caravans, than the commerce which is carried on at Urga; for from this place is brought, monthly, even weekly, to Pekin, not only the same sorts of goods which our caravans bring, but of a better quality than those brought by our caravans; and in so great quantities, that the merchandises which the merchants of Pekin, who go continually between Pekin and Urga to trade with our people, and the goods which the lamas of the Mongols bring from their parts, amount every year to four or five times as much value as the caravans that come to Pekin in the name of his Czarish Majesty.[12]

By the time of Zanabazar's death in 1723 Urga had already become the preeminent monastery in Mongolia in terms of religious authority. A council of seven of the highest ranking lamas (Khamba Nomon Khan, Ded Khamba and five Tsorj) made most of the religious decisions in the city. It had also become the commercial center of Outer Mongolia. From 1733 till 1778 Urga basically moved around in the vicinity of its present location. In 1754 the Erdene Shanzodba Yam (Administration of Ecclesiastical Estate) of Urga was given full authority to supervise the administrative affairs of the shabinar (lay subjects of the Bogd). It also functioned and would continue to function as the chief judicial court of the city. Sunduvdorj was the Erdene Shanzodba at this time. In 1758 the Qianlong Emperor appointed the Khalkha Vice General Sanzaidorj as the first Mongol amban of Urga with full authority to "oversee the Khuree and administer well all the Khutugtu's shabinar".[13] In 1761 a second amban was appointed for the same purpose, a Manchu one. In 1786 a decree was issued in Peking which gave right to the Urga ambans to make final decisions concerning the administrative affairs of Tusheet Khan and Setsen Khan territories. With this, Urga became the highest civil authority in the country. Based on Urga's Mongol governor Sanzaidorj's petition the Qianlong emperor officially recognized an annual ceremony on Mt. Bogd Khan Uul in 1778 and provided the annual imperial donations. The city was the seat not only of the Jebtsundamba Khutugtus, but also of two Qing ambans, and a Chinese trade town (Chinese: 買賣城; pinyin: Măimàichéng) grew "four trees" or 4.24 kilometers east of the city center at the confluence of the Uliastai and Tuul rivers. This trade district was kept at a distance in order not to block the way of pilgrims or defile the holy city (as demanded by the 4th Bogd Jebtsundamba). It had agricultural fields and artificial lakes. The Chinese had large, beautifully decorated shops selling different articles. A pair of highly ornate 11 metre tall inscribed columns (1783) standing in front of the surviving Dari Ekh Temple (1778) in the former Maimaicheng district is now under national protection. The large store Nomtiin Puus (Shop of the Pious Merchant) and ruins of another old Chinese shop are still visible. There were 14 temples in Maimaicheng: 8 Chinese and 6 Mongolian, including the Kunz Bogdiin Sum (Confucius Temple), Odon Sum (Astrological Temple), Tsagaan Malgaitiin Sum (White Hat Mosque of Chinese Muslims), Dari Ehiin Sum (Guanyin Temple), Geser Sum (Guandi Temple), Erleg Khaani Sum (Temple of the Lord of Death), Erliiziin Sum (Temple of the Mixed-Ethnicity People) and Urchuudiin Sum (Temple of Craftsmen). A Zargachiin Yam (Chamber of Judges) located east of the Chinese mosque handled legal affairs of the Chinese.

Since 1778 Urga may have had around 10,000 monks. They were regulated by a monastic rule called the Internal Rule of the Grand Monastery or Yeke Kuriyen-u Doto'adu Durem (for example, in 1797 or the second year of Jiaqing a decree of the 4th Jebtsundamba forbade "singing, playing with archery, myagman, chess, usury and smoking"). Executions were forbidden where the holy temples of the Bogd Jebtsundama could be seen, so capital punishment was carried out a certain distance away from the city. In 1839 the 5th Bogd Jebtsundamba moved his residence to Gandan Hill, an elevated position to the west of the Baruun Damnuurchin markets. A part of the city was moved to nearby Tolgoit. The reason given for this move was that prevailing north-western winds brought the impure air of the Baruun Damnuurchin markets (known for its many Chinese and Russian shops as well as brothels) onto the inviolably sacred area of the Bogd Jebtsundamba's Zuun Khuree temple complex, located just to the east of the markets. Despite this, in 1855 the part of the camp that moved to Tolgoit was brought back to its 1778 location and the 7th Bogd Jebtsundamba moved back to the Zuun Khuree permanently. The Gandan Monastery flourished as a center of philosophical studies (tsanid). Women were not allowed to enter the area and its Yellow Hat monks were forbidden to go to the lay quarters (khoroo) where Red Hat sect monks freely took wives. Urga was visited by many foreign envoys and travelers, including Egor Fedorovich Timkovskii (1820), N.M.Przhevalsky, Pyotr Kozlov, M. De Bourbolon (1860) and A.M.Pozdneev. The Russian embassy of 130 persons which arrived in Urga in January 1806 included Count Yury Golovkin, Count Jan Potocki, Julius Klaproth and Andrey Yefimovich Martynov.[14] In 1863 the Russian Consulate of Urga was opened in a newly built two-storey building on Consul Hill. A small onion-domed Chapel of the Holy Trinity was opened the same year. There were protests from some Urga monks who complained that the Consulate on Consul Hill was higher than the sacred pole of the Bogd Jebtsundamba. Most of the major Mongolian khans and nobles had representative residence quarters in Urga located in the south-east and south-west khoroo lay quarters which they occasionally visited. The south-west lay quarters also included the Tibetan and Buryat quarters and had a number of Red Hat temples, shamanic shrines as well as Yellow Hat temples. The quarters (Amban Khan Khoroo) of the Mongol and Manchu governors of Urga were located in the Zuun Omnod Khoroo (Southeast Khoroo) lay quarters.

-

Panorama of Urga painted by Mongolian painter Jugder in 1913.

-

Detail of the Maimaicheng and Russian consulate in Jugder's 1913 painting.

-

Detail of the South-East Lay Quarters and surrounding areas in Jugder's 1913 painting.

-

Detail of Manjusri monastery on Mount Bogd Khan Uul in Jugder's 1913 painting.

Revolutions of 1911 and 1921 and Communist era

The Moscow trade expedition of the 1910's estimated the population of Urga at 60,000 based on Nikolay Przhevalsky's study in the 1870's.[15] The city's population swelled during the Naadam festival and major religious festivals to more than 100,000. In 1919 the number of monks had reached 20,000, up from 13,000 in 1810.[16] In 1910 the amban Sando went to quell a major fight between Gandan lamas and Chinese traders started by an incident at the Da Yuan shop in the Baruun Damnuurchin market district. He was unable to bring the lamas under control and was forced to flee back to his quarters. In 1911, with the Qing Dynasty in China headed for total collapse, Mongolian leaders in Ikh Khüree for Naadam met in secret on Mount Bogd Khan Uul and resolved to end 220 years of Manchu control of their country. On December 29, 1911 the 8th Jeptsundamba Khutughtu was declared ruler of an independent Mongolia and assumed the title Bogd Khan.[9] Khüree as the seat of the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu was the logical choice for the capital of the new state. However, in the tripartite Kyakhta agreement of 1915 (between Russia, China, Mongolia), Mongolia's status was changed to mere autonomy. In 1919, Mongolian nobles, over the opposition of the Bogd Khan, agreed with the Chinese resident Chen Yi on a settlement of the "Mongolian question" along Qing-era lines, but before this settlement could be put into effect, Khüree was occupied by the troops of Chinese warlord Xu Shuzheng, who forced the Mongolian nobles and clergy to renounce autonomy completely.

In 1921 the city changed hands twice. First, in February 4, 1921, a mixed Russian/Mongolian force led by White Russian warlord Roman von Ungern-Sternberg captured the city, freeing the Bogd Khan from Chinese imprisonment and killing a part of the Chinese garrison. Baron Ungern's capture of Urga was followed by clearing of Mongolia from small gangs of demoralized Chinese soldiers and, at the same time, looting and murder of foreigners, including a vicious pogrom that killed off the [17] [18] [19] Jewish community. On February 22, 1921 the Bogd Khan was once again elevated the Great Khan of Mongolia in Urga.[20] However, at the same time Baron Ungern was taking control of Urga, a Soviet-supported Communist Mongolian force led by Damdin Sükhbaatar was forming up in Russia, and in March they crossed the border. Ungern and his men rode out in May to meet Red Russian and Red Mongolian troops, but suffered a disastrous defeat in June.[21] In July the Communist Soviet-Mongolian army became the second conquering force in six months to enter Urga. Mongolia came to the control of the Soviet Russia. On October 29, 1924 the town was renamed to Ulan Bator ("red hero"), by the advise of T.R. Ryskulov, the Soviet representative in Mongolia.

In the socialist period, and especially following the Second World War, most of the old yurt quarters were replaced by Soviet-style blocks of flats, often financed by the Soviet Union. Urban planning began in the 1950s, and most of the city today is the result of construction from 1960 to 1985.[22] The Transmongolian Railway, connecting Ulan Bator with Moscow and Beijing, was completed in 1956, and cinemas, theaters, museums etc. were erected. On the other hand, most of the temples and monasteries of pre-socialist Khüree were destroyed following the anti-religious purges of the late 1930s. The Gandan monastery was reopened in 1944 when US Vice President Henry Wallace asked to see a monastery during his visit to Mongolia.

Democratic protests of 1989-1990

Ulan Bator was the site of demonstrations that led to Mongolia's transition to democracy and market economy in 1990. On December 10, 1989, protesters outside the Youth Culture Centre called for Mongolia to implement perestroika and glasnost in their full sense. Dissident leaders demanded free elections and economic reform. On January 14, 1990 the protesters, having grown from two hundred to over a thousand, met at the Lenin Museum in Ulan Bator. A demonstration in Sükhbaatar Square on Jan. 21 followed. Afterwards, weekend demonstrations in January and February were held accompanied by the forming of Mongolia's first opposition parties. On March 7, ten dissidents assembled in Sükhbaatar Square and went on a hunger strike. Thousands of supporters joined them. More came on March 8, and the crowd grew more unruly; seventy people were injured and one killed. On March 9 the communist Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party government resigned. The provisional government announced Mongolia's first free elections, which were held in July. The MPRP won the election and resumed power.[23]

Since Mongolia's transition to a market economy in 1990, the city has experienced further growth - especially in the yurt quarters, as construction of new blocks of flats had basically broken down in the 1990s.[citation needed] The population has more than doubled to over one million inhabitants, about 50% of Mongolia's entire population.[citation needed] This causes a number of social, environmental, and transportation problems. In recent years, construction of new buildings has gained new momentum, especially in the city center, and apartment prices have skyrocketed.

2008 protests

In 2008, Ulan Bator was the scene of riots after the Mongolian Democratic, Civic Will Party and Republican parties disputed the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party's victory in the parliamentary elections. Approximately 30,000 people took part in a public meeting led by the opposition parties. After the meeting was over some protestors left the central square and moved on to the nearby headquarters of the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party, attacking and burning the building. A police station was also attacked.[24] At night rioters set fire to the Cultural Palace, where a theatre, museum and National art gallery were vandalised and burned. Torched cars,[25] bank robberies and looting were reported.[24] The organisations in the burning buildings were vandalised and looted. Police used tear gas, rubber bullets and water cannons against stone-throwing protestors.[24] A four-day state of emergency was declared, the capital was placed under a 22:00 to 08:00 curfew, and alcohol sales banned,[26] following which measures rioting did not resume.[27] Five people were killed and hundreds arrested by the police during the suppression of the riots. Human rights groups expressed concerns about the handling of this unprecedented incident by the authorities.[28][29]

Geography and climate

| Ulan Bator | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ulan Bator is located at about 1,350 metres (4,430 ft) above mean sea level, slightly east of the centre of Mongolia on the Tuul River, a subtributary of the Selenge, in a valley at the foot of the mountain Bogd Khan Uul. Bogd Khan Uul is a broad, heavily forested mountain rising 2,250 metres (7,380 ft) to the south of Ulan Bator. It forms the boundary between the steppe zone to the south and the forest-steppe zone to the north. It is also one of the oldest reserves in the world, being protected by law since the 18th century. The forests of the mountains surrounding Ulan Bator are composed of evergreen pines, deciduous larches and birches while the riverine forest of the Tuul River is composed of broad-leaved, deciduous poplars, elms and willows.

Owing to its high elevation, its relatively high latitude, its location hundreds of kilometres from any coast, and the effects of the Siberian anticyclone, Ulan Bator is the coldest national capital in the world,[31] with a monsoon-influenced, cold semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk, USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 3b[32]) that closely borders a subarctic climate. The city features brief, warm summers and long, bitterly cold and dry winters. The coldest January temperatures, usually at the time just before sunrise, are between −36 °C (−33 °F) and −40 °C (−40 °F) with no wind, due to temperature inversion. Most of the annual precipitation of 216 millimetres (8.50 in) falls from June to September. The highest recorded precipitation in the city was 659 mm (26 in) at the Khureltogoot Astronomical Observatory on Mount Bogd Khan Uul. Ulan Bator has an average annual temperature of −2.4 °C (27.7 °F).[30] The city lies in the zone of discontinuous permafrost, which means that building is difficult in sheltered aspects that preclude thawing in the summer, but easier on more exposed ones where soils fully thaw. Suburban residents live in traditional yurts that do not protrude into the soil.[33] Extreme temperatures in the city range from −49 °C (−56 °F) to 38.6 °C (101.5 °F).[34]

| Climate data for Ulan Bator | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | −1.9 (28.6) |

7.7 (45.9) |

18.7 (65.7) |

25.5 (77.9) |

33.8 (92.8) |

34.7 (94.5) |

35.1 (95.2) |

36.9 (98.4) |

30.8 (87.4) |

24.1 (75.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

36.9 (98.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −15.6 (3.9) |

−11.4 (11.5) |

−2 (28.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

16.8 (62.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

15.6 (60.1) |

6.8 (44.2) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−13.7 (7.3) |

5.5 (41.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −24.6 (−12.3) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

0.3 (32.5) |

8.9 (48.0) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.6 (61.9) |

14.7 (58.5) |

7.3 (45.1) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−13.2 (8.2) |

−21.9 (−7.4) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −26.5 (−15.7) |

−24.1 (−11.4) |

−15.4 (4.3) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

2.7 (36.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

9.3 (48.7) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−6 (21.2) |

−16.2 (2.8) |

−23.8 (−10.8) |

−7.01 (19.38) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −44.2 (−47.6) |

−40.6 (−41.1) |

−35.1 (−31.2) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−25.3 (−13.5) |

−36.0 (−32.8) |

−41.6 (−42.9) |

−44.2 (−47.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1.1 (0.04) |

1.7 (0.07) |

2.7 (0.11) |

8.3 (0.33) |

13.4 (0.53) |

41.7 (1.64) |

57.6 (2.27) |

51.6 (2.03) |

26.2 (1.03) |

6.4 (0.25) |

3.2 (0.13) |

2.5 (0.10) |

216.4 (8.53) |

| Average precipitation days | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 9.9 | 11.0 | 13.6 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 50.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 176.1 | 204.8 | 265.2 | 262.5 | 299.3 | 269.0 | 249.3 | 258.3 | 245.7 | 227.5 | 177.4 | 156.4 | 2,791.5 |

| Source: NOAA (1961-1990) [35] | |||||||||||||

Panoramas

Administration and subdivisions

Ulan Bator is divided into nine districts (Düüregs): Baganuur, Bagakhangai, Bayangol, Bayanzürkh, Chingeltei, Khan Uul, Nalaikh, Songino Khairkhan, and Sükhbaatar. Each district is subdivided into Khoroos, of which there are 121.[31]

The capital is governed by a city council (the Citizen's Representatives Hural) with forty members, elected every four years. The city council appoints the mayor. When his predecessor became prime minister in January 2006, former city manager Gombosuren Monkhbayar was elected mayor.[36] Ulan Bator is governed as an independent first-level region, separate from the surrounding Töv Aimag.

The city consists of a central district built in Soviet 1940s and 1950s-style architecture, surrounded by and mingled with residential concrete towerblocks and large yurt quarters. In recent years, many of the towerblock's ground floors have been modified and upgraded to small shops, and many new buildings have been erected, some of them illegally (some private companies erect buildings without the legal licenses or in forbidden places).[citation needed]

Sights

Ulan Bator is a relatively young city and has few historic buildings, Additionally, several temples and monasteries were destroyed during socialism. Mainstream tourist guide books usually recommend the Gandan monastery with the large Janraisig statue, the socialist monument complex at Zaisan with its great view over the city, the Bogd Khan's winter palace, Sukhbaatar square and the nearby Choijin Lama monastery. Additionally, Ulan Bator houses numerous museums, two of the most well-known being the Museum of National History and the Museum of Natural History. Popular destinations for day trips are the Terelj national park, the Manzushir monastery ruins on the southern flank of Bogd Khan Uul, and a large equestrian statue of Genghis Khan erected in 2006. Important shopping districts include the 3rd Microdistrict Boulevard, Peace Avenue around the State Department Store and the Narantuul Black Market area. Ulan Bator has three large cinemas, one modern ski resort, two large indoor stadiums and one large amusement park. Food, entertainment and recreation venues are steadily increasing in variety.

-

A building of the Dambadarjaalin Monastery (1765) in Sukhbaatar District.

-

Ornate inscribed columns (1783) in front of the surviving Dari Ekh Temple (1778) now the Dolma Ling Nunnery .

-

Ger-shaped temple of Dashchoiling Monastery (1778).

-

Only remaining wooden column of the Gungaachoilin Temple (1809) said to have survived burning and sawing in 1938.

-

Tsogchin Dugan Temple (1838).

-

Vajradhara Temple (1841) in the center. Zuu Temple (1869) on left connected by passage built in 1945-1946.

-

Erdem Itgemjit Temple, built in 1893.

-

Winter residence of the Bogd Gegeen, built in 1903. Designed under Tsar Nicholas II.

-

Zanabazar's Fine Arts Museum, built in 1905 by Russian merchant Gudvintsal as a trading shop.

-

Ulan Bator History Museum, built in 1904 by Buryat-Mongol merchant.

-

Side gate and Peace Temple of the Choijin Lama temple complex, built in 1904-1908.

-

West Geser Temple in UB, built in 1919–1920 by Guve Ovogt Zakhar.

-

Residence of Prince Chin Wang Khanddorj (Minister of Foreign Affairs), built in 1913.

-

Holy Trinity Church, built near the old Russian Consulate of 1863.

Monasteries

Among the notable older monasteries is the Choijin Lama Monastery, a Buddhist monastery that was completed in 1908. It escaped the destruction of Mongolian monasteries when it was turned into a museum in 1942.[37] Another is the Gandan Monastery, which dates to the 19th century. Its most famous attraction is a 26.5-meter-high golden statue of Migjid Janraisig.[38] These monasteries are among the very few in Mongolia to escape the wholesale destruction of Mongolian monasteries under Khorloogiin Choibalsan.

Winter Palace

Old Ikh Khüree, once the city was set up as a permanent capital, had a number of palaces and noble residences in an area called Öndgiin sürgiin nutag. The Jebtsundamba Khutughtu, who was later crowned Bogd Khan, had four main imperial residences, which were located between the Middle (Dund gol) and Tuul rivers. The summer palace was called Erdmiin dalai buyan chuulgan süm or Bogd khaanii serüün ord. Other palaces were the White palace (Tsagaan süm or Gьngaa dejidlin), and the Pandelin palace (also called Naro Kha Chod süm), which was situated in the left bank of Tuul River. Some of the palaces were also used for religious purposes.[39] The only palace that remains is the winter palace. The Winter Palace of the Bogd Khan (Bogd khaanii nogoon süm or Bogd khaanii öwliin ordon) remains as a museum of the last monarch. The complex includes six temples, many of the Bogd Khan's and his wife's possessions are on display in the main building.

Museums

Ulan Bator has several museums dedicated to Mongolian history and culture. The Natural History Museum features many dinosaur fossils and meteorites found in Mongolia.[40][41] The National Museum of Mongolia includes exhibits from prehistoric times through the Mongol Empire to the present day.[42][43] The Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts contains a large collection of Mongolian art, including works of the 17th century sculptor/artist Zanabazar, as well as Mongolia's most famous painting, One Day In Mongolia by B. Sharav.[44][45] The Mongolian Theatre Museum presents the history of the performing arts in Mongolia. The city's former Lenin Museum announced plans in January 2013 to convert to a museum showcasing dinosaur and other prehistoric fossils.[46]

Pre-1778 artifacts that never left the city since its founding include the Vajradhara statue made by Zanabazar himself in 1683 (the city's main deity kept at the Vajradhara temple), a highly ornate throne presented to Zanabazar by the Kangxi Emperor (before 1723), a sandalwood hat presented to Zanabazar by the Dalai Lama (c. 1663), Zanabazar's large fur coat which was also presented by the Kangxi Emperor and a great number of original statues made by Zanabazar himself (e.g. the Green Tara).

Puzzle Toys Museum displays a comprehensive collection of complex wooden toys to be assembled by players using sophisticated methods.

Opera house

The Ulan Bator Opera House, situated in the center of the city, hosts concerts and musical performances.

Sükhbaatar Square

Sükhbaatar Square, in the government district, is the center of Ulan Bator. The square is 31,068 square meters in size.[47] In the middle of Sükhbaatar Square, there is a statue of Damdin Sükhbaatar on horseback. The spot was chosen because that was where Sükhbaatar's horse had urinated (a good omen) on July 8, 1921 during a gathering of the Red Army. On the north side of Sükhbaatar Square is the Mongolian Parliament building, featuring a large statue of Chinggis Khan at the top of the front steps. Peace Avenue (Enkh Taivny Urgon Chuloo), the main thoroughfare through town, runs along the south side of the square.[48]

Zaisan Memorial

The Zaisan Memorial, a memorial to Soviet soldiers killed in World War II, sits on a hill south of the city. The Zaisan Memorial includes a Soviet tank paid for by the Mongolian people and a circular memorial painting which in the socialist realism style depicts scenes of friendship between the peoples of Soviet Union and Mongolia. Visitors who make the long climb to the top are rewarded with a panoramic view of the whole city down in the valley.

National Sport Stadium

National Sports Stadium is the main sporting venue. The Naadam festival is held here every July.

Artificial Lake Castle

Artificial Lake Castle was built in 1969, when the National Amusement Park was established in the centre of the Mongolian capital Ulan Bator.

Surroundings

Gorkhi-Terelj National Park, a nature preserve with many tourist facilities, is approximately 70 km from Ulan Bator. Accessible via paved road. The 40 meter high Genghis Khan Equestrian Statue, 54 km from Ulan Bator, is the largest equestrian statue in the world.

Embassies and Consulates

Among the countries that have diplomatic facilities in Ulan Bator are Australia, Austria, Bulgaria, Canada, China, Cuba, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, India, Japan, Kazakhstan, Laos, Russia, Slovakia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Vietnam.[49][50][51]

Symbols

The official symbol of Ulan Bator is the garuḍa, a mythical bird in both Buddhist and Hindu scriptures called Khan Garuda or Khangar'd (Mongolian: Хангарьд) by Mongols.

Emblem

The garuḍa appears on Ulan Bator's emblem. In its right hand is a key, a symbol of prosperity and openness, and in its left is a lotus flower, a symbol of peace, equality, and purity. In its talons it is holding a snake, a symbol of evil of which it is intolerant. On the garuḍa's forehead is the soyombo symbol, which is featured on the flag of Mongolia.

Flag

The city's flag is sky blue with the garuḍa arms in the center.[citation needed]

Education

Ulan Bator has six major universities:

- National University of Mongolia

- Science and Technological University of Mongolia

- Mongolian State University of Agriculture

- Health Science University of Mongolia[52]

- Mongolian State Pedagogical University

- Mongolian University of Art and Culture.

There are a number of other universities in the city, including Humanities University (www.humanities.mn).

Even though relatively small, the Institute of Finance and Economics is popular as an economics school in Mongolia.

The National Library of Mongolia has a wide selection of English-language texts on Mongolian subjects.[53]

The American School of Ulaanbaatar and the International School of Ulaanbaatar both offer Western-style K-12 education in English for Mongolian nationals and foreign residents.[54][55]

Libraries

National Library

The National Library of Mongolia is located in Ulan Bator and includes an extensive historical collection, items in non-Mongolian languages, and a special children's collection.[56]

Public libraries

The Metropolitan Central Library of Ulaanbataar, sometimes also referred to as the Ulan Bator Public Library, is a public library with a collection of about 500,000 items. It has an impressive 232,097 annual users and a total of 497,298 loans per year. It does charge users a registration fee of 3800 to 4250 tugrik, or about USD 3.29 to 3.68. The fees may be the result of operating on a budget under $176,000 per year. They also host websites on classical and modern Mongolian literature and food, in addition to providing free Internet access.[56]

In 1986 the Ulan Bator government created a centralized system for all public libraries in the city, known as the Metropolitan Library System of Ulan Bator (MLSU). It is also known by its official name, Dashdorjiin Natsagdorj, who was the founder of modern Mongolian literature. This system coordinates management, acquisitions, finances, and policy among public libraries in the capital, in addition to providing support to school and children's libraries.[57] Other than the Metropolitan Central Library, the MLSU has four branch libraries. They are in the Chingeltei District (established in 1946), in the Han-Uul District (established in 1948), in the Bayanzurkh District (established in 1968), and in the Songino-Hairkhan District (established in 1991). There is also a Children's Central Library, which was established in 1979.[58]

University libraries

- Library of Mongolian State University of Education

- Library of the Academy of Management

- Library of the National University of Mongolia

- Institutes of the Academy of Sciences (3 Department Libraries)

- Library of the Institute of Language and Literature

- Library of the Institute of History

- Library of the Institute of Finance and Economics

- Library of the National University of Mongolia

- Library of the Agriculture University

Digital libraries

The International Children's Digital Library (ICDL) is an organization that publishes numerous children's books in different languages on the web in child-friendly formats. In 2006 they began service in Mongolia and have made efforts to provide access to the library in rural areas. The ICDL effort in Mongolia is part of a larger project funded by the World Bank, and administered by the Mongolian Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, called the Rural Education And Development Project (READ).[59] Because Mongolia lacks a publishing industry, and few children's books, the idea has been to "spur the publishing industry to create 200 new children's books for classroom libraries in grades 1-5." After these books were published and distributed to teachers they were also published online with the rest of the ICDL collection. While a significant portion of this project is supported by outside sources, an important component is to include training of Mongolian staff in order to make it continue in an effective way.[60][61] The project is also designed to show Mongolia's youth that they can take part in the larger digital culture.

The Press Institute in Ulan Bator oversees the Digital Archive of Mongolian Newspapers. It is a collection of 45 newspaper titles with a particular focus on the years after the fall of communism in Mongolia.[62] The project was supported by the British Library's Endangered Archives Programme.

The Metropolitan Central Library in Ulaanbaatar maintains a digital Monthly News Archive.[63]

Special libraries

An important resource for academics is the American Center for Mongolian Studies (ACMS), also based in Ulaanbaatar. Its goal is to facilitate research between Mongolia and the rest of the world and to foster academic partnerships. To help achieve this end, it operates a research library with a reading room and computers for Internet access. ACMS has 1,500 volumes related to Mongolia in numerous languages that may be borrowed with a deposit. It also hosts an online library that includes special reference resources and access to digital databases, including a digital book collection.[64]

There is a Speaking Library at School 116 for the visually impaired. This is a project funded by the Zorig Foundation, and the collection is largely based on materials donated by Mongolian National Radio. "A sizable collection of literature, know-how topics, training materials, music, plays, science broadcasts are now available to the visually impaired at the school."[65]

The Mongolia-Japan Center for Human Resources Development maintains a library in Ulaanbaatar consisting of about 7,800 items. The materials in the collection have a strong focus on both aiding Mongolians studying Japanese and books in Japanese about Mongolia. It includes a number of periodicals, textbooks, dictionaries, and audio-visual materials. Access to the collection does require payment of a 500 Tugrug fee, though materials are available for loan. They also provide audio-visual equipment for collection use and internet access for an hourly fee. There is also an information retrieval reference service for questions that cannot be answered by their collection.[66]

Archives

There is a manuscript collection at the Danzan Ravjaa Museum of theological, poetic, medicinal, astrological, and theatrical works. It consists of literature written and collected by the monk Danzan Ravjaa, who is famous for his poetry. The British Library's Endangered Archives Programme funded a project to take digital images of unique literature in the collection, however, it is not clear where the images are stored today.[67]

Transport

Interurban and international: Ulaanbaatar is served by the Chinggis Khaan International Airport (formerly Buyant Ukhaa Airport). It is 18 km southwest of the city.[68] Chinggis Khaan airport is the only airport in Mongolia that offers international flights. Flights to Ulaanbaatar are available from Tokyo, Seoul, Berlin, Moscow, Irkutsk, Hong Kong, Beijing, Bishkek and Istanbul.[69] There are rail connections to the Trans-Siberian railway via Naushki and to the Chinese railway system via Jining. Ulaanbaatar is connected by road to most of the major towns in Mongolia, but most roads in Mongolia are unpaved and unmarked and road travel can be difficult. Even within the city, not all roads are paved and some of the ones that are paved are not in good condition.[70]

Intra-urban: The national and municipal governments regulate a wide system of private transit providers which operate numerous bus lines around the city. There is also a Ulaanbaatar trolleybus system. A secondary transit system of privately owned microbuses (passenger vans) operates alongside these bus lines. Additionally, Ulaanbaatar has over 4000 taxis.[71] The capital has 418.2 km of road, of which 76.5 are paved.[72]

Air pollution

Air pollution is a serious problem in Ulaanbaatar, especially in winter. Concentrations of certain types of particulate matter (PM10) regularly exceed WHO recommended maximum levels by more than a dozen times. They also exceed the concentrations measured in northern Chinese industrial cities. During the winter months, smoke regularly obscures vision and can even lead to problems with air traffic at the local airport.

Sources of the pollution are mainly the simple stoves used for heating and cooking in the city's yurt quarters, but also the local power plants (fueled on coal). The problem is compounded by Ulaanbaatar's location in the a valley between relatively high mountains, which shield the city from the winter winds and thus obstruct air circulation.[73][74]

Ulaanbaatar's residents are very aware of the city's pollution problems (during the winter months, pollution levels and their relation to WHO recommended levels are regularly reported on TV, in a manner similar to weather reports) and ways to amend the situation have been discussed for years, however no easy solution has been found yet.

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Ulan Bator is twinned with:

|

Notable individuals

See also

Appearances in Fiction

In the novel "Alas, Babylon" by Pat Frank, the city was a relocation site for the Soviet leadership. In the novel it had a medium-wave station for communications.[84]

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

- ^ Ulaanbaatar Statistic Bulletin May.2008 http://statis.ub.gov.mn/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=170&Itemid=99999999

- ^ a b Ulaanbaatar Official Web Portal

- ^ Протоколы 1-го Великого Хуралдана Монгольской Народной Республики. Улан-Батор-Хото,1925

- ^ Histoire generale des voyages, 1753, p.61

- ^ Staunton, Sir George Thomas Narrative of the Chinese embassy to the Tourgouth Tartars 1821, London, p. 30

- ^ Darkhan Chin Wang Khoshuu of the Khalkha Tusheet Khan Aimag.

- ^ Khalkha Ochirbat Tusheet Khan Aimag

- ^ This Shireet tsagaan nuur is located in Övörkhangai's Bürd sum. P. Enkhbat, O. Pürev, Улаанбаатар, Ulaanbaatar 2001, p. 9f

- ^ a b Brief history of Ulaanbaatar

- ^ Kohn, Michael Lonely Planet Mongolia 4th edition, 2005 ISBN 1-74059-359-6, p. 52

- ^ John Bell, Travels from St. Petersburgh in Russia, to various parts of Asia (Volume 1), 1763, London, p. 344

- ^ John Bell, Lorenz Lange, Travels from St. Petersburgh in Russia, to various parts of Asia (Volume 2), 1788, London, p. 233

- ^ Zsuzsa Majer, Krisztina Teleki , Monasteries and Temples of Bogdiin Khuree, Ikh Khuree or Urga, the Old Capital City of Mongolia in the First Part of the Twentieth Century, 2006, Ulaanbaatar, p. 25

- ^ Timkowski, George Travels of the Russian mision through Mongolia to China and residence in Peking in the years 1820-1821 Vol.1, 1827 London, p. 128

- ^ From Khutagtiin Khuree to Niislel Khuree. Presentation of the Director of the General Archives Authority D.Ulziibaatar.

- ^ From Khutagtiin Khuree to Niislel Khuree. Presentation of the Director of the General Archives Authority D.Ulziibaatar.

- ^ OTHEN, CHRISTOPHER. Bright Review.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Palmer, James (2009). The Bloody White Baron.

- ^ Bisher, Jamie. White Terror: Cossack Warlords Of The Trans-Siberian. p. 276.

- ^ Kuzmin, S.L. History of Baron Ungern: an Experience of Reconstruction. Moscow: KMK, 2011, p. 165-200

- ^ Kuzmin, p.250-300

- ^ Montsame News Agency. Mongolia. 2006, ISBN 99929-0-627-8, p. 33-34

- ^ Rossabi, Morris Modern Mongolia: From Khans to Commissars to Capitalists 2005, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-24419-2. pp. 1-28

- ^ a b c "BBC.Mongolia calls state of emergency". BBC News. 2008-07-01. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ "ABC News.Mongolia clamps down after 5 killed in unrest". Abc.net.au. 2008-07-02. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ "BBC.Fatal clashes in Mongolia capital the situation had stabilised". BBC News. 2008-07-02. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ "BBC. Streets calm in riot-hit Mongolia". BBC News. 2008-07-03. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ "Amnesty International Are the Mongolian Authorities getting away with murder?". Amnesty.org. 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ Human Rights Coalition statement[dead link]

- ^ a b "Climatological Normals of Ulaanbaatar". Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ^ a b Montsame News Agency. Mongolia. 2006, ISBN 99929-0-627-8, p. 35

- ^ "World Hardiness Zones Map"

- ^ geography.about.com coldcapital.html

- ^ "Extreme Temperatures Around the World". Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ "Ulan Bator Climate Normals 1961-1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ Writethru: Ulan Bator Mayor Enkhbold elected Mongolia's new PM, Xinhua news agency, Beijing, 25 January 2006. Accessed: 25 October 2010

- ^ Choijin Lama Monastery

- ^ Kohn, pp. 63-4

- ^ Majer, Zsuzsa. "Monasteries and Temples of Bogdiin Khьree, Ikh Khьree or Urga, the Old Capital City of Mongolia in the First Part of the Twentieth Century" (PDF). Budapest: Documentation of Mongolian Monasteries. p. 36. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Natural History Museum

- ^ Kohn, p. 60

- ^ Kohn, pp. 61, 66

- ^ "National Museum". Nationalmuseum.mn. 2012-03-21. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ Kohn, p. 61

- ^ "Zanazabar Museum of Fine Arts". Zanabazarmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ Branigan, Tania (January 27, 2013). "It's goodbye Lenin, hello dinosaur as fossils head to Mongolia museum". The Guardian. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Montsame News Agency. Mongolia. 2006, ISBN 99929 0-627-8, p. 34

- ^ Kohn, p. 52

- ^ Kohn, Michael. Lonely Planet Mongolia. 2008, fifth edition, ISBN 978 1-74104-578-9, p. 255

- ^ "GoAbroad.com". Embassiesabroad.com. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ E Mongol List of Embassies located in Mongolia

- ^ www.hsum.edu.mn Health Science University of Mongolia

- ^ Kohn, pp. 54-5

- ^ American School of Ulaanbaatar[dead link]

- ^ "International School of Ulaanbaatar". Isumongolia.edu.mn. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ a b "Metropolitan Central Library of Ulaanbaatar". Nla.gov.au. 2004-03-01. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ "Library History." Ulaanbataar Metropolitan Central Library. 1 June 2002. Accessed 25 June 2008.

- ^ "Metropolitan Central Library Named After D. Natsagdorj." Ulaanbataar Public Library, 1 June 2002. Accessed 25 June 2008.

- ^ ""Rural Education and Development (READ) Project (formerly Rural Education Support Project)" World Bank. Accessed 1 July 2008". Web.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ "Bederson, Ben. "No Hotel, Tent: The International Children's Digital Library Goes to Mongolia." International Children's Digital Library, 2006. Accessed 7 May 2008". Childrenslibrary.org. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ Bederson, Ben. “No Road, Drive: The ICDL Goes to the Mongolian Countryside.” International Children's Digital Library, 2007. Accessed 7 May 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. "Digital Librarian Lends Expertise to Mongolian Project." University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries Newsletter. 52 (2007). Accessed 8 May 2008". Uwm.edu. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ "Monthly News Archive." Metropolitan Central Library. Accessed 25 June 2008.

- ^ "American Center for Mongolian Studies Library Homepage. American Center for Mongolian Studies, Ulaanbataar. Accessed 7 May 2008". Mongoliacenter.org. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ "Sumiyabazar, Ch. "Speaking Library at School No. 116." UB Post: Mongolia's English Weekly News. Thursday, November 08, 2007. Accessed June 6, 2008". Ubpost.mongolnews.mn. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ "Library." Mongolia-Japan Center for Human Resources Development Japan-center.mn. Accessed 29 June 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Humphrey, Caroline. "The Treasures of Danzan Ravja." The British Library Endangered Archives Programme. No date. Accessed 27 June 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Kohn, p. 88

- ^ "MIAT Route Map". Miat.com. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ "Transport in Mongolia". Web.worldbank.org. 2006-07-20. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ Montsame News Agency. Mongolia. 2006, Foreign Service Office of Montsame News Agency, ISBN 99929-0-627-8, p. 90

- ^ Montsame News Agency. Mongolia. 2006, ISBN 99929-0-627-8, p. 36

- ^ Hasenkopf, Christa. "Clearing the Air". World Policy Journal (Spring 2012). Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ The World Bank (December 2009). "Mongolia: Air Pollution in Ulaanbaatar – Initial Assessment of Current Situation and Effects of Abatement Measures" (PDF). Sustainable Development Series: Discussion Paper. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f "Улаанбаатар хотын ах, дүү хотууд". ub.gov.mn. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ Seoul Metropolitan Government. "Sister Cities".

- ^ Контакты с иностранными городами Внешние связи — официальный сайт администрации города Красноярска Template:Ref-ruTemplate:Ref-enTemplate:Ref-de

- ^ Irkutsk sister cities[dead link]

- ^ "Chairman of the Committee for External Relations of St. Petersburg". Translate.google.com. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ Ulan Ude looking for sister cities[dead link]

- ^ Denver Sister Cities[dead link]

- ^ "Business Gold Coast. Gold Coast Business News . Business Events . Business Resources - Sister Cities & International Partnerships". BusinessGC. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ "Delhi to London, it's a sister act". The Times Of India. July 7, 2002.

- ^ Frank, Pat (1959). Alas, Babylon. New York: Perennial 2005 (Lippincott 1959). ISBN 978-0060741877.

External links

- Ulaanbaatar General Information about Ulan-Bator, Up-to-date Template:En icon

- Digital map of Ulaanbaatar yurt districts including Template:En icon

- Ulaanbaatar Travel Guide 2012 Ulaanbaatar Travel Guide Template:En icon

- "Urga or Da Khuree" from A. M. Pozdneyev's Mongolia and the Mongols

Ulaanbaatar travel guide from Wikivoyage

Ulaanbaatar travel guide from Wikivoyage