User:Jokulhlaup/draftarticle5

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

{{Geobox|River}}

The River Trent is one of the major rivers of England. Its source is in Staffordshire on the southern edge of the Pennines near Biddulph Moor. It then flows in an arc through the Midlands The river passes through Stoke-on-Trent, Burton-upon-Trent and Nottingham before joining the River Ouse at Trent Falls to form the Humber Estuary, which in turn flows into the North Sea.

Forming a once significant boundary between the north and south of England) until it joins the River Ouse at Trent Falls to form the Humber Estuary, which empties into the North Sea below Hull and Immingham.

The Trent is unusual amongst English rivers in that it flows north (for the second half of its route), and in exhibiting a tidal bore, the "Trent Aegir". The area drained by the river includes most of the northern Midlands.

Name[edit]

The name "Trent" comes from a Celtic word possibly meaning "strongly flooding". More specifically, the name may be a contraction of two Celtic words, tros ("over") and hynt ("way").[1] This may indeed indicate a river that is prone to flooding. However, a more likely explanation may be that it was considered to be a river that could be crossed principally by means of fords, i.e. the river flowed over major road routes. This may explain the presence of the Celtic element rid (c.f. Welsh rhyd, "ford") in various place names along the Trent, such as Hill Ridware, as well as the Old English‐derived ford. Another translation is given as "the trespasser", referring to the waters flooding over the land.[2] According to Koch at the University of Wales,[3] the name Trent derives from the Romano-British Trisantona, a Romano-British reflex of the combined Proto-Celtic elements *tri-sent(o)-on-ā- (through-path-AUG-F-) ‘great feminine thoroughfare’.[3]

Prehistory[edit]

In the Pleistocene epoch (1.7 million years ago) the River Trent rose in the Welsh hills and flowed almost east from Nottingham through the present Vale of Belvoir to cut a gap through the limestone ridge at Ancaster and thence to the North Sea[4] At the end of the Wolstonian Stage (c. 130,000 years ago) a mass of stagnant ice left in the Vale of Belvoir caused the river to divert north along the old Lincoln river, through the Lincoln gap. In a following glaciation (Devensian, 70,000 BC) the ice held back vast areas of water – called Glacial Lake Humber – in the current lower Trent basin. When this retreated, the Trent adopted its current course into the Humber.[5]

Migration of course in historic times[edit]

Unusually for an English river, the channel altered significantly in historic times, and has been described as being similar to the Mississippi in this respect, especially in its middle reaches, where there are a numerous old meanders and cut-off loops.[6]

An abandoned channel at Repton is described on an old map as 'Old Trent Water', records show that this was once the main navigable route, with the river having switched to a more northerly course in the 18th century.[7] Further downstream at Hemington, archaeologists have found the remains of a series of medieval bridges across another abandoned channel.[8][9] Researchers using aerial photographs, and historical maps have identified many of these palaeochannel features, one well documented example, being the cut-off meander at Sawley.[10][11] The river's propensity to change course is referred to in Shakespeare's play Henry IV - Part 1:

- Methinks my moiety, north from Burton here,

- In quantity equals not one of yours:

- See how this river comes me cranking in,

- And cuts me from the best of all my land

- A huge half-moon, a monstrous cantle out.

- I'll have the current in this place damm'd up;

- And here the smug and silver Trent shall run

- In a new channel, fair and evenly;

- It shall not wind with such a deep indent,

- To rob me of so rich a bottom here.[a][13][14]

Henry Hotspur's speech complaining about the river has been linked to the meanders near West Burton,[15] however, given the wider context of the play with its fictional tripartite division of England following a possible revolt, it is thought that Hotspur’s intentions are of a grander design, diverting the river east, back to its ancestral course towards the Wash such that he would benefit from a much larger share of the divided Kingdom. Downstream of the Burton-on-Trent, the river increasingly trends northwards, cutting off a portion of Nottinghamshire and nearly all of Lincolnshire from his share, north of the Trent.[16][17] The idea for this scene, may have been based on the disagreement regarding a mill weir near Shelford Manor, between local landowners the Earl of Shrewsbury and Sir Thomas Stanhope which culminated with a long diversion channel being dug to bypass the mill.[18] This took place in 1593 so would have been a contemporary topic in the Shakespearian period.[16]

This speech by Henry Hotspur complaining about the river is not considered to be about a local alteration in its course near West Burton[19] nor Burton upon Stather[17] but due to the fact that downstream of Burton upon Trent the river increasingly trends northwards, cutting off a portion of Nottinghamshire and nearly all of Lincolnshire from Hotspur’s share in the play's fictional division of England following a possible revolt. His intention being to block the river, and alter its course, such that it ran east, possibly to the Wash so that he benefitted from a much larger share of the divided Kingdom.[17] The idea for the passage may have been based on the disagreement regarding a mill weir at Shelford, between local landowners the Earl of Shrewsbury and Sir Thomas Stanhope which culminated with a long diversion channel being dug to bypass the mill.

This took place in 1593 so would have been a contemporary topic in the Shakespearian period.

Course[edit]

The Trent rises on the Staffordshire moorlands near the village of Biddulph Moor, from a number of sources including the Trent Head Well. It is then joined by other small streams to form the Head of Trent, which flows south, to the only reservoir along its course at Knypersley. Downstream of the reservoir it passes through Stoke on Trent and merges with the Lyme, Fowlea and other brooks that drain the 'six towns' of the Staffordshire Potteries to become the River Trent. On the southern fringes of Stoke, it passes through the landscaped parkland of Trentham Gardens.[20]

The river then continues south through the market town of Stone, and after passing the village of Salt, it reaches Great Haywood, where it is spanned by the Elizabethan Essex Bridge near Shugborough Hall, at this point the River Sow joins it. The Trent now flows south-east past the town of Rugeley until it reaches Kings Bromley where it meets the Blithe. Following the confluence with the Swarbourn, it passes Alrewas and reaches Wychnor, where it is crossed by the A38 dual carriageway, which follows the route of the Roman Ryknild Street. The river turns north-east where it is joined by its largest tributary; the Tame, and immediately afterwards by the Mease; creating a larger river that now flows through a broad floodplain. The river continues north-east passing the village of Walton-on-Trent until it reaches the large town of Burton upon Trent.

The river in Burton is crossed by a number of bridges including the ornate Victorian Ferry Bridge that links Stapenhill to the town.[20] To the north-east of Burton the river is joined by the River Dove at Newton Solney and enters Derbyshire, before passing between the villages of Willington and Repton where it turns directly east to reach Swarkestone Bridge, King's Mill, Weston and Aston-on-Trent.[20]

At Shardlow, where the Trent and Mersey Canal begins, the river also meets the Derwent at Derwent Mouth. Following this confluence, the river turns north-east and is joined by the Soar before reaching the outskirts of Nottingham, where it is joined by the River Erewash near the Attenborough nature reserve. As it enters the city, it passes the suburbs of Beeston, Clifton and Wilford; where it is joined by the Leen. On reaching West Bridgford it flows beneath Trent Bridge near the cricket ground of the same name, and beside Nottingham Forest football ground until it reaches Holme Sluices.[20]

Downstream of Nottingham it passes Radcliffe on Trent, Stoke Bardolph and Burton Joyce before reaching Gunthorpe with its bridge, lock and weir. The river now flows north-east below the Toot and Trent Hills before reaching Hazelford Ferry, Fiskerton and Farndon. To the north of Farndon, beside the Staythorpe Power Station the river splits, with one arm passing Averham and Kelham, and the other arm, which is navigable, being joined by the Devon before passing through the market town of Newark-on-Trent and beneath the town's castle walls. The two arms recombine at Crankley Point beyond the town, where the river turns due north to pass North Muskham and Holme to reach Cromwell Weir, below which the Trent becomes tidal.[20]

The now tidal river, meanders across a wide floodplain, at the edge of which are located riverside villages such as Carlton and Sutton on Trent, Besthorpe and Girton. After passing the site of High Marnham power station, it reaches the only toll bridge along its course at Dunham on Trent. Downstream of Dunham the river passes Church Laneham and reaches Torksey, where it meets the Foss Dyke navigation which connects the Trent to Lincoln and the River Witham. Further north at Littleborough is the site of the Roman town of Segelocum, where a Roman road once crossed the river.[20][21]

It then reaches the town of Gainsborough with its own Trent Bridge. The river frontage in the town is lined with warehouses, that were once used when the town was an inland port, many of which have been renovated for modern use. Downstream of the town the villages are often named in pairs, reflecting the fact that they were once linked by a river ferry between the two settlements. These villages include West and East Stockwith, Owston and East Ferry and West and East Butterwick.[22][23][24] At West Stockwith the Trent is joined by the River Idle. The last bridge over the river is at Keadby where it is joined both by the Stainforth and Keadby Canal, and also by the River Torne.[20]

Downstream of Keadby the river progressively widens, passing Amcotts and Flixborough to reach Burton upon Stather and finally Trent Falls. At this point, between Alkborough and Faxfleet the river joins the Ouse to form the Humber which flows into the North Sea.[20]

Catchment[edit]

The Trent basin covers a large part of the Midlands, and includes the majority of the counties of Staffordshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire and the West Midlands; but also includes parts of Lincolnshire, South Yorkshire, Warwickshire and Rutland. The catchment is located between the drainage basins of the Severn and the Warwickshire Avon to the south and west, the Weaver to the north-west, the tributaries of the Yorkshire Ouse to the North and the East Anglian river basins of the Welland, Witham and Ancholme to the East.[25][26]

A distinctive feature of the catchment is the marked variation in the topography and character of the landscape, which varies from the upland moorland headwaters of the Dark Peak, where the highest point of the catchment is the Kinder Scout plateau at 634 metres (2,080 ft); through to the intensively farmed and drained flat fenland areas that exist alongside the lower tidal reaches, where ground levels can equal sea level. These lower reaches are protected from tidal flooding by a series of floodbanks and defences.[27][28][29]

Elsewhere there is a distinct contrast between the open limestone areas of the White Peak in the Dove catchment, and the large woodland areas, including Sherwood Forest in the Dukeries area of the Idle catchment, the upland Charnwood Forest, and the National Forest in the Soar and Mease drainage basins respectively.[25]

| Land use[30] |

Land use is predominantly rural, with some three-quarters of the Trent catchment given over to agriculture. This ranges from moorland grazing of sheep in the upland areas, through to improved pasture and mixed farms in the middle reaches, where dairy farming is important. Intensive arable farming of cereals and root vegetables, chiefly potatoes and sugar beet occurs in the lowland areas, such as the Vale of Belvoir and the lower reaches of the Trent, Torne and Idle.[30] Water level management is important in these lowland areas, and the local watercourses are often maintained by Internal Drainage Boards and their successors with improved drainage often being assisted by the use of pumping stations to lift water into embanked carrier rivers, which subsequently discharge into the Trent.[25]: 29 [31]

The less populated rural areas are offset, by a number of large urbanised conurbations, including Stoke-on-Trent, Birmingham and the surrounding Black Country; there are also a number of separate cities in the basin including Leicester, Derby and Nottingham, together these contain the majority of the 6 million people who live in the catchment.[25]

What is notable is that the majority of these urban areas are in the upper reaches of either the Trent itself, as is the case with Stoke, or the tributaries. For example, Birmingham lies at the upper end of the Tame, and Leicester is located towards the head of the Soar. Whilst this is not unique for an English river, it does mean that there is an ongoing legacy of issues relating to urban runoff, pollution incidents, and effluent dilution both from sewage treatment, industry and coal mining. Historically, these issues resulted in a considerable deterioration in the water quality of both the Trent, and its tributaries, especially the Tame.[30]

Geology[edit]

Underlying the upper reaches of the Trent, are formations of Millstone Grit and Carboniferous Coal Measures which include layers of sandstones, marls and coal seams. The river crosses a band of Triassic Sherwood sandstone at Sandon, and it meets the same sandstone again as it flows beside Cannock Chase, between Great Haywood and Armitage, there is also another outcrop between Weston-on-Trent and Kings Mill.[32][33]

Downstream of Armitage the solid geology is primarily Mercia Mudstones, the course of the river following the arc of these mudstones as they pass through the Midlands all the way to the Humber. The mudstones are not exposed by the bed of the river, as there is a layer of gravels and then alluvium above the bedrock. In places, however the mudstones do form river cliffs, most notably at Gunthorpe and Stoke Lock near Radcliffe on Trent, the village being named after the distinctive red coloured strata.[34]

The low range of hills, which have been formed into a steep set of cliffs overlooking the Trent between Scunthorpe and Alkborough are also made up of mudstones, but are of the younger (Rhaetic) Penarth Group.[33][32]

In the wider catchment the geology is more varied, ranging from the Precambrian rocks of the Charnwood Forest, through to the Jurassic limestone that forms the Lincolnshire Edge and the eastern watershed of the Trent. The most important in terms of the river are the extensive sandstone and limestone aquifers that underlie many of the tributary catchments. These include the Sherwood sandstones that occur beneath much of eastern Nottinghamshire, the Permian Lower Magnesian limestone and the carboniferous limestone in Derbyshire. Not only do these provide baseflows to the major tributaries, the groundwater is an important source for public water supply.[33]

| Gravel Terraces of the River Trent[35] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | Age thousand yrs BP |

Stage |

| Eagle Moor | > 400 | Anglian |

| Etwall / Whisby Farm |

297 | Early Wolstonian |

| Egginton / Balderton |

195 | Late Wolstonian |

| Beeston / Scarle |

80 | Devensian |

| Holme Pierrepont | 26 | Devensian |

| Hemington | 10 | Flandrian |

Sand, gravels and alluvium deposits that overlie the mudstone bedrock occur almost along the entire length of the river, and are an important feature of the middle and lower reaches, with the alluvial river silt producing fertile soils that are used for intensive agriculture in the Trent valley. Beneath the alluvium are widespread deposits of sand and gravel, which also occur as gravel terraces considerably above the height of the current river level. There is thought to be a complex succession of at least six separate gravel terrace systems along the river, deposited when a much larger Trent flowed through the existing valley, and along its ancestral routes through the water gaps at Lincoln and Ancaster.[36]

This ‘staircase’ of flat topped terraces was created as a result of successive periods of deposition and subsequent down cutting by the river, a product of the meltwater and glacially eroded material produced from ice sheets at the end of glacial periods through the Pleistocene epoch between 450k and 12k years BP. Contained within these terraces is evidence of the mega fauna that once lived along the river, the bones and teeth of animals such as the woolly mammoth, bison and wolves that existed during colder periods have all been identified. Another notable find in a related terrace system near Derby from a warmer interglacial period, was the Allenton hippopotamus.[36][35]

The lower sequences of these terraces have been widely quarried for sand and gravel, and the extraction of these minerals continues to be an important industry in the Trent Valley, with some 3 million tonnes of aggregates being produced each year. Once worked out, the remaining gravel pits which are usually flooded by the relatively high water table have been reused for a wide variety of purposes. These include recreational water activities, and once rehabilitated, as nature reserves and wetlands.[37]

During the end of the last (Devensian) glacial period the formation of Lake Humber in the lowest reaches of the river, meant that substantial lake bed clays and silts were laid down to create the flat landscape of the Humberhead levels. These levels extend across the Trent valley, and include the lower reaches of the Eau, Torne and Idle. In some areas, successive layers of peat were built up above the lacustrine deposits during the Holocene period, which created lowland mires such as the Thorne and Hatfield moors. [38]

Hydrology[edit]

The topography, geology and land use of the Trent catchment, all have a direct influence on the hydrology of the river. The variation in these factors is also reflected in the contrasting runoff characteristics and subsequent inflows of the principal tributaries. The largest of these is the River Tame, which contributes nearly a quarter of the total flow for the Trent, with the other significant tributaries being the Derwent at 18%, Soar 17%, the Dove 13%, and the Sow 8%.[39]: 36–47 Four of these main tributaries, including the Dove and Derwent which drain the upland Peak District, all join within the middle reaches, giving rise to a comparatively energetic river system for the UK.[40]

Rainfall[edit]

Rainfall in the catchment generally follows topography[41] with the highest annual rainfall of 1,450 millimetres (57 in) and above occurring over the high moorland uplands of the Derwent headwaters to the north and west, with the lowest of 580 millimetres (23 in), in the lowland areas to the north and east.[42] Rainfall totals in the Tame are not as high as would be expected from the moderate relief, due to the rain shadow effect of the Welsh mountains to the east, reducing amounts to an average of 691 millimetres (27.2 in) for the tributary basin.[41][43] The average for the whole Trent catchment is 720 millimetres (28 in) which is significantly lower than the average for United Kingdom at 1,101 millimetres (43.3 in) and lower than that for England at 828 millimetres (32.6 in).[44][45][46]

Like other large lowland British rivers, the Trent is vulnerable to long periods of rainfall caused by sluggish low pressure weather systems repeatedly crossing the basin from the Atlantic, especially during the autumn and winter when evaporation is at its lowest. This combination can produce a water-logged catchment that can respond rapidly in terms of runoff, to any additional rainfall. Such conditions occurred in February 1977, with widespread flooding in the lower reaches of the Trent when heavy rain produced a peak flow of nearly 1,000 cubic metres per second (35,000 cu ft/s) at Nottingham. In 2000 similar conditions occurred again, with above average rainfall in the autumn being followed by further rainfall, producing flood conditions in November of that year.[47][48][49]

Another meteorological risk, although one that occurs less often, is that related to the rapid melting of snow lying in the catchment. This can be a result of a sudden rise in temperature after a prolonged cold period, or when combined with extensive rainfall. Many of the largest historical floods were caused by snowmelt, but the last such episode occurred when the bitter winter of 1946-7 was followed by a rapid thaw due to rain in March 1947 and caused severe flooding all along the Trent valley.[47][50]

At the other extreme, extended periods of low rainfall can also cause problems. The lowest flows for the river were recorded during the drought of 1976, following the dry winter of 1975/6. Flows measured at Nottingham were exceptionally low by the end of August, and were given a drought return period of greater than one hundred years.[51]

Discharge[edit]

| Discharge of the River Trent at various locations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauging Station |

County | Discharge (average) |

Discharge (maximum) |

Catchment Area |

||||||

| m3/s | cfs | m3/s | cfs | km2 | mi2 | |||||

| Stoke on Trent | 0.6 | 21 | 55 | 1,900 | 53 | 20 | [52][53] | |||

| Great Haywood | 4.4 | 160 | 98 | 3,500 | 325 | 125 | [52][54] | |||

| Yoxall | 12.8 | 450 | 206 | 7,300 | 1,229 | 475 | [52][55] | |||

| Drakelow | 36.1 | 1,270 | 385 | 13,600 | 3,072 | 1,186 | [52][56] | |||

| Shardlow | 51.6 | 1,820 | 480 | 17,000 | 4,400 | 1,700 | [52][57] | |||

| Colwick | 83.8 | 2,960 | 1,018 | 36,000 | 7,486 | 2,890 | [52][48] | |||

| North Muskham | 88.4 | 3,120 | 1,000 | 35,000 | 8,231 | 3,178 | [52][58] | |||

The river's levels and flows are measured at several points along its course, at a number of gauging stations. At Stoke-on-Trent in the upper reaches, the average flow is only 0.6 cubic metres per second (21 cu ft/s), which increases considerably to 4.4 cubic metres per second (160 cu ft/s), at Great Haywood, as it includes the flow of the upper tributaries draining the Potteries conurbation. At Yoxall, the flow increases to 12.8 cubic metres per second (450 cu ft/s) due to the input of larger tributaries including the Sow and Blithe. At Drakelow upstream of Burton the flow increases nearly three-fold to 36.1 cubic metres per second (1,270 cu ft/s), due to the additional inflow from the largest tributary the Tame. At Colwick near Nottingham, the average flow rises to 83.8 cubic metres per second (2,960 cu ft/s), due to the combined inputs of the other major tributaries namely the Dove, Derwent and Soar. The last point of measurement is North Muskham here the average flow is 88.4 cubic metres per second (3,120 cu ft/s), a relatively small increase due to the input of the Devon, and other smaller Nottinghamshire tributaries.[52][59]

The Trent has marked variations in discharge, with long term average monthly flows at Colwick fluctuating from 45 cubic metres per second (1,600 cu ft/s) in July during the summer, and increasing to 151 cubic metres per second (5,300 cu ft/s) in January.[60][61] During lower flows the Trent and its tributaries are heavily influenced by effluent returns from sewage works, especially the Tame where summer flows can be made up of 90% effluent. For the Trent this proportion is lower, but with nearly half of low flows being made up of these effluent inflows, it is still significant. There are also baseflow contributions from the major aquifers in the catchment.[62][63][64]

break[edit]

River Trent at Colwick

Average monthly flows of Trent in cubic metres per second measured at Colwick (Nottingham).[61]

Sediment[edit]

In the lower tidal reaches the Trent has a high sediment load, this fine silt which is also known as ‘warp', was used to improve the soil by a process known as warping, whereby river water was allowed to flood into adjacent fields through a series of warping drains, enabling the silt to settle out across the land. Up to 0.3 metres (0.98 ft) of deposition could occur in a single season, and depths of 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) have been accumulated over time at some locations. A number of the smaller Trent tributaries are still named as warping drains, such as Morton warping drain, near Gainsborough.[67]

Warp was also used as a commercial product, after being collected from the river banks at low tide, it was transported along the Chesterfield Canal to Walkeringham where it was dried out and refined to be eventually sold as a silver polish for cutlery manufacturers. [68][69]

Floods[edit]

| Largest floods on the River Trent at Nottingham[70] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Date | Level at Trent Bridge | Peak Flow | |||

| m | ft | m3/s | cfs | |||

| 1 | February 1795 | 24.55 | 80.5 | 1,416 | 50,000 | |

| 2 | October 1875 | 24.38 | 80.0 | 1,274 | 45,000 | |

| 3 | March 1947 | 24.30 | 79.7 | 1,107 | 39,100 | |

| 4 | November 1852 | 24.26 | 79.6 | 1,082 | 38,200 | |

| 5 | November 2000 | 23.80 | 78.1 | 1,019 | 36,000 | |

| Normal / Avg flow | 20.7 | 68 | 84 | 3,000 | ||

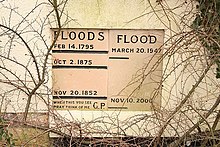

The Trent is widely known for its tendency to cause significant flooding along its course, and there is a well documented flood history extending back for some 900 years. In Nottingham the heights of significant historic floods from 1852 have been carved into a bridge abutment next to Trent Bridge, with flood marks being transferred from the medieval Hethbeth bridge that pre-dated the existing 19th century crossing. Historic flood levels have also been recorded at Girton and on the churchyard wall at Collingham.[71][15][70]

One of the earliest recorded floods along the Trent was in 1141, and like many other large historical events was caused by the melting of snow following heavy rainfall, it also caused a breach in the outer floodbank at Spalford. Some of the earliest floods can be assessed by using Spalford bank as a substitute measure for the size of a particular flood, as it has been estimated that the bank only failed when flows were greater than 1,000 cubic metres per second (35,000 cu ft/s), the bank was also breached in 1403 and 1795.[72]

Early bridges were vulnerable to floods, and in 1309 many bridges were washed away or damaged by severe winter floods, including Hethbeth Bridge. In 1683 the same bridge was partially destroyed by a flood that also meant the loss of the bridge at Newark. Historical archives often record details of the bridge repairs that followed floods, as the cost of these repairs or pontage had to be raised by borrowing money and charging a local toll.[15][72]

The largest known flood was the Candlemas flood of February 1795, which followed an eight week period of harsh winter weather, rivers froze which that meant mills were unable to grind corn, and then followed a rapid thaw. Due to the size of the flood and the ice entrained in the flow, nearly every bridge along the Trent was badly damaged or washed away. The bridges at Wolseley, Wychnor and the main span at Swarkestone were all destroyed.[73][74] In Nottingham, residents of Narrow Marsh were trapped by the floodwaters in their first floor rooms, boats were used to take supplies to those stranded. Livestock was badly affected, 72 sheep drowned in Wilford and ten cows were lost in Bridgford.[75] The vulnerable flood bank at Spalford was breached again, floodwaters spreading out across the low lying land, even reaching the River Witham and flooding Lincoln. Some 81 square kilometres; 31 square miles (20,000 acres) were flooded for a period of over three weeks.[15][76][77]

A description of the breach was given as follows:

"The bank is formed upon a plain of sandy nature, and when it was broken in 1795, the water forced an immense breach, the size of which may be judged from the fact that eighty loads of faggots and upwards of four hundred tons of earth were required to fill up the hole, an operation which took several weeks to complete."

The flood bank was subsequently strengthened and repaired, following further floods in 1824 and 1852.[76]

The principal flood of the 19th century and the second largest recorded, was in October 1875. In Nottingham a cart overturned in the floodwaters near the Wilford Road and six people drowned, dwellings nearby were flooded to a depth of 1.8 metres (6 ft). Although not quite as large as 1795 this flood devastated many places along the river, at Burton upon Trent much of the town was inundated, with flooded streets and houses, and dead animals floating past in the flood. Food was scarce, "in one day 10,000 loaves had to be sent into the town and distributed gratuitously to save people from famine".[78] In Newark the water was deep enough to allow four grammar school boys, to row across the countryside to Kelham. The flood marks at Girton show that this flood was only 4 inches lower than that of 1795, when the village was flooded to a depth of 0.91 metres (3 ft).[15]

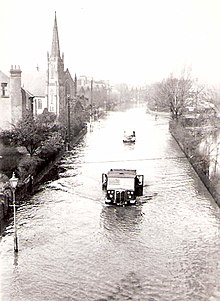

On the 17-18 March 1947 the Trent which had been rising ever higher, overtopped its banks in Nottingham. Large parts of the city and surrounding areas were flooded with 9,000 properties and nearly a hundred industrial premises affected some to first floor height. The suburbs of Long Eaton, West Bridgford and Beeston all suffered particularly badly.[79][50][80] Two days later, in the lower tidal reaches of the river, the peak of the flood combined with a high spring tide to flood villages and 2,000 properties in Gainsborough. River levels dropped when the floodbank at Morton breached, resulting in the flooding of some 200 square kilometres; 50,000 acres (78 sq mi) of farmland in the Trent valley.[29][80]

Flooding on the Trent can also be caused by the effects of storm surges independently of fluvial flows, a series of which occurred in October and November 1954, resulting in the worse tidal flooding experienced along the lower reaches. These floods revealed the need for a tidal protection scheme, which would cope with the flows experienced in 1947 and the tidal levels from 1954, and subsequently the floodbanks and defences along the lower river were improved to this standard with the works being completed in 1965.[29][81] In December 2013, the largest storm surge occurred on the Trent since the 1950s, when a low pressure weather system combined with high tides, and strong winds. The river levels generated by this surge overtopped the tidal flood defences in the area near Keadby and Burringham, flooding 50 properties.[82]

The fifth largest flood recorded at Nottingham occurred in November 2000, with widespread flooding of low lying land along the Trent valley, including many roads and railways. The flood defences around Nottingham and Burton constructed in the 1950s, following the 1947 event, stopped any major urban flooding, but problems did occur in undefended areas such as Willington and Gunthorpe, and again at Girton where 19 houses were flooded.[49] The flood defences in Nottingham that protect 16,000 homes and those in Burton where they prevent 7,000 properties from flooding were reassessed after this flood, and were subsequently improved between 2006 and 2012.[79][83]

[edit]

Nottingham seems to have been the ancient head of navigation until the Restoration, due partly to the difficult navigation of the Trent Bridge. Navigation was then extended to Wilden Ferry, near to the more recent Cavendish Bridge, as a result of the efforts of the Fosbrooke family of Shardlow.

Later, in 1699, Lord Paget, who owned coal mines and land in the area, obtained an Act of Parliament to extend navigation up to Fleetstones Bridge, Burton, despite opposition from the people of Nottingham. Lord Paget seems to have funded the work privately, building locks at King's Mill and Burton Mills and several cuts and basins. The Act gave him absolute control over the building of any wharfs and warehouses above Nottingham Bridge. Lord Paget leased the navigation and the wharf at Burton to George Hayne, while the wharf and warehouses at Wilden were leased by Leonard Fosbrooke, who held the ferry rights and was a business partner of Hayne. The two men refused to allow any cargo to be landed which was not carried in their own boats, and so created a monopoly.[84]

In 1748, the merchants from Nottingham attempted to break this monopoly by landing goods on the banks and into carts, but Fosbrooke used his ferry rope to block the river, and then created a bridge by mooring boats across the channel, and employing men to defend them. Hayne subsequently scuppered a barge in King's Lock, and for the next eight years goods had to be transhipped around it. Despite a Chancery injunction against them, the two men continued with their action. Hayne's lease ran out in 1762, and Lord Paget's son, the Earl of Uxbridge, gave the new lease to the Burton Boat Company.[84]

The Trent and Mersey Canal was authorised by Act of Parliament in 1766, and construction from Shardlow to Preston Brook, where it joined the Bridgewater Canal, was completed by 1777.[85] The canal ran parallel to the upper river to Burton on Trent, where new wharfs and warehouses at Horninglow served the town, and the Burton Boat Company were unable to repair the damaged reputation of the river created by their predecessors.[86] Eventually in 1805, they reached an agreement with Henshall & Co., the leading canal carriers, for the closure of the river above Wilden Ferry. Though the river is no doubt legally still navigable above Shardlow, it is probable that the agreement marks the end of the use of that stretch of the river as a commercial navigation.[87]

The Lower River[edit]

The first improvement of the lower river was at Newark, where the channel splits into two. The residents of the town wanted to increase the use of the branch nearest to them, and so an Act of Parliament was obtained in 1772 to authorise the work. Newark Navigation Commissioners were created, with powers to borrow money to fund the construction of two locks, and to charge tolls for boats using them. The work was completed by October 1773, and the separate tolls remained in force until 1783, when they were replaced by a 1 shilling (5p) toll whichever channel the boats used.[86]

Users of the Trent and Mersey Canal, the Loughborough Canal and the Erewash Canal next demanded major improvements to the river down to Gainsborough, including new cuts, locks, dredging and a towing path suitable for horses. The Dadfords, who were engineers on the Trent and Mersey Canal, estimated the cost at £20,000, but the proposal was opposed by landowners and merchants on the river, while the Navigator, published in 1788, estimated that around 500 men who were employed to bow-haul boats would have lost their jobs. Agreement could not be reached, and so William Jessop was asked to re-assess the situation. He suggested that dredging, deepening, and restricting the width of the channel could make significant improvements to the navigable depth, although cuts would be required at Wilford, Nottingham bridge and Holme. This proposal formed the basis for an Act of Parliament obtained in 1783, which also allowed a horse towing path to be built. The work was completed by September 1787, and dividends of 5 per cent were paid on the capital in 1786 and 1787, rising to 7 per cent, the maximum allowed by the Act, after that. Jessop carried out a survey for a side cut and lock at Sawley in 1789, and it was built by 1793.[86]

At the beginning of the 1790s, the Navigation faced calls for a bypass of the river at Nottingham, where the passage past Trent Bridge was dangerous, and the threat of a canal running parallel to the river, which was proposed by the Erewash and the Trent and Mersey Canal companies. In order to retain control of the whole river, they supported the inclusion of the Beeston Cut in the bill for the Nottingham Canal, which prevented the Erewash Canal company from getting permission to build it, and then had the proposal removed from the Nottingham Canal company's bill in return for their support of the main bill. The parallel canal was thwarted in May 1793, when they negotiated the withdrawal of the canal bill by proposing a thorough survey of the river which would lead to their own legislation being put before parliament. William Jessop carried out the survey, assisted by Robert Whitworth, and they published their report on 8 July 1793. The major proposals included a cut and lock at Cranfleet, where the River Soar joins the Trent, a cut, locks and weirs at Beeston, which would connect with the Nottingham Canal at Lenton, and a cut and lock at Holme Pierrepont. An Act of Parliament was obtained in 1794, and the existing proprietors subscribed the whole of the authorised capital of £13,000 (equivalent to £1,590,000 in 2021),[88] themselves.[89]

The aim of the improvements was to increase the minimum depth from 2 feet (0.6 m) to 3 feet (0.9 m). By early 1796, the Beeston cut was operational, with the Cranfleet cut following in 1797, and the Holme cut in 1800, with the whole works being finished by 1 September 1801. The cost exceeded the authorised capital by a large margin, with the extra being borrowed, but the company continued to pay a 7 per cent dividend on the original shares and on those created to finance the new work. In 1823 and again in 1831, the Newark Navigation Commissioners proposed improvements to the river, so that larger vessels could be accommodated, but the Trent Navigation Company were making a healthy profit, and did not see the need for such work.[89]

Competition[edit]

The arrival of the railways resulted in significant change for the Company. Tolls were reduced to retain the traffic, wages were increased to retain the workforce, and they sought amalgamation with a railway company. The Nottingham and Gainsborough Railway offered £100 per share in 1845, but this was rejected. Tolls fell from £11,344 (equivalent to £1,060,000 in 2021),[88] in 1839 to £3,111 (equivalent to £310,000 in 2021),[88] in 1855. Many of the connecting waterways were bought by railway companies, and gradually fell into disrepair. In an attempt to improve the situation, the Company toyed with the idea of cable-hauled steam tugs, but instead purchased a conventional steam dredger and some steam tugs. The cost of improvements was too great for the old company, and so an Act of Parliament was obtained in 1884 to restructure the company and raise additional capital. Failure to raise much of the capital resulted in another Act being obtained in 1887, with similar aims and similar results. A third Act of 1892 reverted the name to the Trent Navigation Company, and this time, some improvements were carried out.[90]

With traffic still between 350,00 and 400,000 tonnes per year, Frank Rayner became the engineer in 1896, and the company were persuaded that major work was necessary if the navigation was to survive. The engineer for the Manchester Ship Canal, Sir Edward Leader Williams, was commissioned to survey the river, while negotiations with the North Staffordshire Railway, who owned the Trent and Mersey Canal and had maintained its viability, ensured that some of the clauses from previous Acts of Parliament did not prevent progress. A plan to build six locks between Cromwell and Holme, and to dredge this section to ensure it was 60 feet (18 m) wide and 5 feet (1.5 m) deep was authorised by an Act of Parliament obtained in 1906. Raising finance was difficult, but some was subscribed by the chairman and vice-chairman, and construction of Cromwell Lock began in 1908. The Newark Navigation Commissioners financed improvements to Newark Town lock at the same time, and dredging of the channel was largely funded by selling the 400,000 tonnes of gravel removed from the river bed. At 188 by 30 feet (57.3 by 9.1 m), Cromwell lock could hold a tug and three barges, and was opened on 22 May 1911. The transport of petroleum provided a welcome increase to trade on the river, but little more work was carried out before the onset of the First World War.[90]

Modernisation[edit]

Increased running costs after the First World War could not be met by increasing the tolls, as the company had no statutory powers to do so, and so suggested that the Ministry of Transport should take over the navigation, which they did from 24 September 1920. Tolls were raised, and a committee recommended improvements to the river. Nottingham Corporation invested some £450,000 on building the locks authorised by the 1906 Act, starting with Holme lock on 28 September 1921, and finishing with Hazelford lock, which was formally opened by Neville Chamberlain on 25 June 1926. A loan from Nottingham Corporation and a grant from the Unemployment Grants Committee enabled the Company to rebuild Newark Nether lock, which was opened on 12 April 1926.[90]

In the early 1930s, the Company considered enlarging the navigation above Nottingham, in conjunction with improvements to the River Soar Navigation, between Trent Lock and Leicester. There were also negotiations with the London and North Eastern Railway, who were responsible for the Nottingham Canal between Trent Lock and Lenton. Plans for new larger locks at Beeston and Wilford were dropped when the Trent Catchment Board opposed them. The Grand Union declined to improve the Soar Navigation, because the Trent Navigation Company could not guarantee 135,000 tons of additional traffic. The Company also considered a plan to reopen the river to Burton, which would have involved the rebuilding of Kings Mills lock, and the construction of four new locks. An extra set of gates were added to Cromwell lock in 1935, effectively creating a second lock, while the Lenton to Trent Lock section was leased from the LNER in 1936, and ultimately purchased in 1946.[90]

Frank Rayner, who had been with the Company since 1887, and had served as its engineer and later general manager since 1896, died in December 1945. Sir Ernest Jardine, who as vice-chairman had partly funded the first lock at Cromwell in 1908, died in 1947, and the company ceased to exist in 1948, when the waterways were nationalised. The last act of the directors was to pay a 7.5 per cent dividend on the shares in 1950. Having taken over responsibility for the waterway, the Transport Commission enlarged Newark Town lock in 1952, and the flood lock at Holme was removed to reduce the risk of flooding in Nottingham. More improvements followed between 1957 and 1960. The two locks at Cromwell became one, capable of holding eight Trent barges, dredging equipment was updated, and several of the locks were mechanised. Traffic rose from 620,000 tonnes in 1951 to 1,017,356 tonnes in 1964, but all of this was below Nottingham. Commercial carrying above Nottingham ceased during the 1950s, to be replaced by pleasure cruising.[90]

Although commercial use of the river has declined, the lower river between Cromwell and Nottingham can still take large motor barges up to around 150 feet (46 m) in length[85] with a capacity of approx 300 tonnes.[91] Barges still transport gravel from pits at Girton and Besthorpe to Goole and Hull.[92]

[edit]

The river is legally navigable for some 117 miles (188 km) below Burton upon Trent. However for practical purposes, navigation above the southern terminus of the Trent and Mersey Canal (at Shardlow) is conducted on the canal, rather than on the river itself. The canal connects the Trent to the Potteries and on to Runcorn and the Bridgewater Canal.

Down river of Shardlow, the non-tidal river is navigable as far as the Cromwell Lock near Newark, except in Nottingham (Beeston Cut & Nottingham Canal) and just west of Nottingham, where there are two lengths of canal, Sawley and Cranfleet cuts. Below Cromwell lock, the Trent is tidal, and therefore only navigable by experienced, well-equipped boaters. Navigation lights and a proper anchor and cable are compulsory. Associated British Ports, the navigation authority for the river from Gainsborough to Trent Falls, insist that anyone in charge of a boat must be experienced at navigating in tidal waters.[85][93]

Between Trent Falls and Keadby, coastal vessels that have navigated through the Humber still deliver cargoes to the wharves of Grove Port, Neap House, Keadby, Gunness and Flixborough. Restrictions on size mean that the largest vessels that can be accommodated are 100m long and 4,500 tonnes.[94][95] The use of a maritime pilot on the Trent is not compulsory for commercial craft, but is suggested for those without any experience of the river. Navigation can be difficult, and there have been a number of incidents with ships running aground and in one case, striking Keadby Bridge. The most recent occurence involved the Celtic Endeavour being aground near Gunness for ten days, finally being lifted off by a high tide.[96][97][98]

Experience is especially necessary at Trent Falls, a lonely spot where the Trent joins the Yorkshire Ouse, to form the Humber estuary. The timetables of flows and tides of the two rivers and the estuary are very complex here, and vary through the lunar cycle. Boats coming down the Trent on an ebbing tide often have to anchor or beach themselves (sometimes in the dark) at Trent Falls to wait for the next incoming tide to carry them up the Ouse.

Trent Aegir[edit]

At certain times of the year, the lower tidal reaches of the Trent experience a moderately large tidal bore (up to five feet (1.5m) high), commonly known as the Trent Aegir (named for the Norse sea god). The Aegir occurs when a high spring tide meets the downstream flow of the river.[99] The funnel shape of the river mouth exaggerates this effect, causing a large wave to travel upstream as far as Gainsborough, Lincolnshire, and sometimes beyond. The Aegir cannot travel much beyond Gainsborough as the shape of the river reduces the Aegir to little more than a ripple, and weirs north of Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire stop its path completely.

The literal North/South divide[edit]

The Trent historically marked the boundary between Northern England and Southern England. For example the administration of Royal Forests was subject to a different Justice in Eyre north and south of the river, and the jurisdiction of the medieval Council of the North started at the Trent.[100] Some traces of the former division remain: the Trent marks the boundary between the provinces of two English Kings of Arms, Norroy and Clarenceux.[101][102] This divide was also described in Michael Drayton's epic topographical poem, Poly-Olbion, The Sixe and Twentieth Song, 1622:

And of the British floods, though but the third I be,

Yet Thames and Severne both in this come short of me,

For that I am the mere of England, that divides

The north part from the south, on my so either sides,

that reckoning how these tracts in compasse be extent,

Men bound them on the north, or on the south of Trent [103]

Pollution[edit]

On 7 October 2009 the government announced that the Trent had suffered a serious pollution incident when cyanide and ammonia from partially treated sewage found its way into the river, killing thousands of fish.[104]

Places along the Trent[edit]

Cities and towns on or close to the river include:

- Stoke-on-Trent

- Stone

- Rugeley

- Burton upon Trent

- Castle Donington

- Derby

- Long Eaton

- Beeston

- Nottingham

- Newark-on-Trent

- Gainsborough

Crossing the Trent[edit]

Prior to the mid 18th century there were few permanent crossings of the river with only four bridges downstream of the Tame confluence at Burton, Swarkestone, Nottingham and Newark. There were, however, over thirty ferries that operated along its course, and numerous fords, where passage was possible, their locations indicated by the suffix ‘ford’ in many riverside place-names such as Hanford, Bridgford, and Wilford.[105][106]

Glover noted in 1823 that all three types of crossing were still in use on the Derbyshire section of the Trent, but that the fords were derelict and dangerous. These fording points only allowed passage across the river when water levels were low, when the river was in flood a long detour could be required.[107] One of the earliest known fords was the crossing at Littleborough, constructed by the Romans it was paved with flagstones, and supported by substantial timber pilings.[21] The importance of these fords was demonstrated by their inclusion in the 1783 navigation Act, which limited any dredging at these sites so that they remained less than 0.61 metres (2 ft) deep.[108]

Ferries often replaced these earlier fording points, and were essential where the water was too deep, such as the tidal section of the lower river. As they were a source of income, they were recorded in the Domesday Book (Latin - passage aquae) at a number of locations including Weston on Trent and Fiskerton, both of which were still in operation in the middle of the 20th century. The ferry boats used along the Trent ranged in size from small rowing boats, to flat decked craft that could carry livestock, horses, and in some case their associated carts or wagons.[105][109]

Wilden ferry, near Shardlow was first recorded in 1310, and was unusual in that it replaced a bridge, rather than visa-versa. A series of earlier medieval bridges had all been lost due to floods, in what was historically an unstable, meandering reach of the river. The ferry itself was replaced by Cavendish Bridge in 1760, which was also damaged beyond repair by a flood in March 1947, requiring a temporary bailey bridge to be used until a new concrete span was constructed in 1957.[110][111]

The delays caused when crossing by ferry often prompted the need for a replacement bridge, such was the case at Willington, Gunthorpe and Gainsborough where the ferry was replaced by a toll bridge.[105][112]

At Stapenhill near Burton, there were similar calls for a new bridge, a tally of usage showed that the foot ferry was being used 700 times per day. The new Ferry Bridge was opened in 1889, although it needed the financial support of the brewer and philanthropist Michael Bass to pay for the construction, and later in 1898 to purchase the existing ferry rights so that it became free of tolls.[113][114]

The toll bridges were mostly bought out by the county councils in the 19th century following government reforms, one of the earliest being Willington in 1898, the first toll free crossing was marked by a procession across the bridge and a day of celebration.[115][116] The only toll bridge that remains across the Trent is at Dunham, although it is free to cross on Christmas and Boxing Day.[117]

Power stations[edit]

The tall chimneys and concave shaped cooling towers of the many power stations are a dominant and familiar presence within the open landscape of the Trent valley, which has been widely used for power generation since the 1940s.[118]

The primary reason for locating so many generating stations beside the Trent was the availability of sufficient amounts of cooling water from the river. This combined with the nearby supplies of fuel in the form of coal from the Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire coalfields, and the existing railway infrastructure meant that a string of twelve large power stations were originally constructed along its banks.[119] At one time these sites provided a quarter of the electricity needs of the UK, giving rise to the epithet 'Megawatt Valley'.[118]

Once these early stations reached the end of their functional life, they were usually demolished, although in some cases the sites have been retained and redeveloped as gas fired power stations.[118]

In downstream order, the power stations that continue to use, or have used the river as their source of cooling water are: Meaford, Rugeley, Drakelow, Willington, Castle Donington, Ratcliffe-on-Soar, Wilford, Staythorpe, High Marnham, Cottam, West Burton and Keadby.[118][120]

The three largest remaining coal-fired stations at Ratcliffe, Cottam and West Burton still use domestic coal supplies, although this is now being replaced by imported coal brought by ship from abroad.[121][122]

There is one hydroelectric power station on the river, at Beeston Weir.[123]

Recreation on the Trent[edit]

Along with other major rivers in the Midlands, the Trent is widely used for recreational activities, both on the water and along its riverbanks. The National Watersports Centre at Holme Pierrepont, near Nottingham combines facilities for many of these sports, including rowing, sailing and whitewater canoeing.[124][125]

The Trent Valley Way created in 1998 as a long distance footpath, enables walkers to enjoy the combined attractions of ‘the river’s rich natural heritage and its history as an inland navigation’. Extended in 2012, the route now runs from Trent Lock in the south through to Alkborough where the river meets the Humber. It combines riverside and towpath sections, with other paths to villages and places of interest in the wider valley.[126][127][128][129]

Historically swimming in the river was popular, in 1770 at Nottingham there were two bathing areas on opposite banks at Trent Bridge which were improved in 1857 with changing sheds and an assistant. Similar facilities were present in 1870 on the water meadows at Burton-on-Trent, which also had its own swimming club. Open water swimming still takes place at locations including Colwick Park Lake adjacent to the river, with its own voluntary lifeguards.[130][131][132][125]

Rowing clubs have existed at Burton, Newark and Nottingham since the mid-1800s, with various regattas taking place between them, both on the river and on the rowing course at the national watersports centre.[133][134][135]

Both whitewater and flat water canoeing is possible on the Trent, with published guides and touring routes being listed for the river. There is a canoe slalom course at Stone, a purpose built 700m artificial course at Holme Pierrepont, and various weirs including those at Newark and Sawley are all used for whitewater paddling. Various canoe and kayak clubs paddle on the river including those at Stone, Burton, and Nottingham. [136][137] [138] [139][140][141]

Established in 1886 the Trent valley sailing club is one of two clubs that use the river for dingy sailing, regattas, and events. There are also a number of clubs that sail on the open water that has been created as a result of flooded gravel workings which include Hoveringham, Girton, and Attenborough.[142]

Organised trips on cruise boats have long been a feature of the Trent, at one time steam launches took passengers from Trent Bridge to Colwick Park, similar trips run today but in reverse, starting from Colwick and passing through Nottingham they use boats known as the Trent Princess and Trent Lady. Others trips run from Newark castle, and two converted barges; the Newark Crusader and Nottingham Crusader, provide river cruises for disabled people via the St John Ambulance Waterwing scheme.[143] [144]

Tributaries[edit]

Although Spenser endowed the 'The beauteous Trent' with 'thirty different streams'[b] the river is joined by more than twice that number of different tributaries,[146] of which the largest in terms of flow is the Tame which drains most of the West Midlands, including Birmingham and the Black Country. The second and third largest are the Derwent and the Dove respectively; together these two rivers drain the majority of Derbyshire and Staffordshire, including the upland areas of the Peak District.[52]

The Soar which drains the majority of the county of Leicestershire, could also be considered as the second largest tributary, as it has a larger catchment area than the Dove or Derwent, but its discharge is significantly less than the Derwent, and lower than the Dove.[52]

In terms of rainfall the Derwent receives the highest annual average rainfall, whereas the Devon, which has the lowest average rainfall is the driest catchment of those tabulated.[147]

| Statistics of the Trent’s largest tributaries | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | County [c] | Length | Catchment Area | Discharge | Rainfall [d] | Max. Altitude | Refs | |||||

| km | mi | km2 | mi2 | m3/s | cfs | mm | in | m | ft | |||

| Blithe | 47 | 29 | 167 | 64 | 1.16 | 41 | 782 | 30.8 | 281 | 922 | [e][52][146] | |

| Devon | 47 | 29 | 377 | 146 | 1.57 | 55 | 591 | 23.3 | 170 | 560 | [f][52][146] | |

| Derwent | 118 | 73 | 1,204 | 465 | 18.58 | 656 | 982 | 38.7 | 634 | 2,080 | [g][52][146] | |

| Dove | 96 | 60 | 1,020 | 390 | 13.91 | 491 | 935 | 36.8 | 546 | 1,791 | [h][52][146] | |

| Erewash | 46 | 29 | 194 | 75 | 1.87 | 66 | 708 | 27.9 | 194 | 636 | [i][52][146] | |

| Greet | 18 | 11 | 66 | 25 | 0.30 | 11 | 655 | 25.8 | 153 | 502 | [j][52][146] | |

| Idle | 55 | 34 | 896 | 346 | 2.35 | 83 | 650 | 26 | 205 | 673 | [k][52][146] | |

| Leen | 39 | 24 | 124 | 48 | 0.67 | 24 | 686 | 27.0 | 185 | 607 | [l][52][146] | |

| Soar | 95 | 59 | 1,386 | 535 | 11.73 | 414 | 641 | 25.2 | 272 | 892 | [m][52][146] | |

| Sow | 38 | 24 | 601 | 232 | 6.33 | 224 | 714 | 28.1 | 234 | 768 | [n][52][146] | |

| Tame | 95 | 59 | 1,500 | 580 | 27.84 | 983 | 691 | 27.2 | 291 | 955 | [o][52][146] | |

| Torne | 44 | 27 | 361 | 139 | 0.89 | 31 | 615 | 24.2 | 145 | 476 | [p][52][146] | |

List of Tributaries[edit]

Tributaries of the Trent

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alphabetical listing of tributaries, extracted from the Water Framework Directive list of water bodies for the River Trent:[146]

|

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Large, Andrew; Petts, Geoffrey (1996). "Historical channel-floodplain dynamics along the River Trent" (PDF). Applied Geography. 16 (3). Elsevier Science: 191–209. doi:10.1016/0143-6228(96)00004-5.

- Barber, Charles (1993). The English Language: a historical introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78570-9.

- Cumberlidge, Jane (1998). Inland Waterways of Great Britain (7th Ed.). Imray Laurie Norie and Wilson. ISBN 0-85288-355-2.

- Hadfield, Charles (1970). The Canals of the East Midlands. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4871-X.

- Hadfield, Charles (1985). The Canals of the West Midlands. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8644-1.

- Koch, J.T. (15 Mar 2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- May, Jeffrey (1977). Prehistoric Lincolnshire (History of Lincolnshire). Lincoln: History of Lincolnshire Committee. ISBN 978-0-902668-00-3.

- Nicholson (2006). Nicholson Guides Vol 6: Nottingham York and the North East. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-721114-2.

- Owen, C.C. (1978). Burton on Trent: the development of industry. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 978-0-85033-218-6.

- Stone, Richard (2005). The River Trent. Phillimore. ISBN 1-86077-356-7.

Notes[edit]

- ^ It is considered that Shakespeare’s use of the word smug means smooth, as in placid or tranquil.[12]

- ^ In the epic poem the The Faerie Queene [145]

- ^ Indicative county shown

- ^ Rainfall is Annual Average 1961-90 for the catchment to the Gauging Station

- ^ Blithe measured at Hamstall Ridware

- ^ Devon measured at Cotham - Altitude from Ordnance Survey Map

- ^ Blithe measured at Church Wilne

- ^ Dove measured at Marston on Dove

- ^ Erewash measured at Sandiacre

- ^ Greet measured at Southwell

- ^ Idle measured at Mattersey

- ^ Leen measured at Triumph Road, Lenton

- ^ Soar measured at Kegworth

- ^ Sow measured at Milford

- ^ Tame measured at Hopwas

- ^ Torne measured at Auckley

- ^ Tributary names from Ordnance Survey maps added where list amalgamated river reaches

- ^ River Order - 1 being closest to Trent Falls

References[edit]

- ^ University of Wales Online Dictionary

- ^ Barber 1993, p. 101.

- ^ a b Koch 2006

- ^ Posnansky, M. The Pleistocene Succession in the Middle Trent Basin. Proc. Geologists' Assoc 71 (1960), pp.285–311

- ^ May 1977.

- ^ Large & Petts 1996, p. 192

- ^ Large & Petts 1996, p. 200

- ^ "Medieval Timber Bridge Unearthed". The Independent. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Ripper, S. and Cooper L.P., 2009, The Hemington Bridges: "The Excavation of Three Medieval Bridges at Hemington Quarry, Near Castle Donington, Leicestershire", Leicester Archaeology Monograph

- ^ Large & Petts 1996, p. 198

- ^ "The Trent Valley: palaeochannel mapping from aerial photographs" (PDF). Trent Valley GeoArchaeology. Retrieved 28th-March-2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Cresswell, Julia, ed. (2010). Oxford dictionary of word origins. Oxford University Press. p. 407. ISBN 9780199547937.

- ^ William Shakespeare, Henry IV, Pt.I., Act III, Sc. I

- ^ Complete Works of William Shakespeare, William Shakespeare, p433, 2007, ISBN 1-84022-557-2, accessed May 2009

- ^ a b c d e Everard Leaver Guilford (1912). "Memorials of old Nottinghamshire" (Memorials of old Nottinghamshire. ed.). London: G. Allen. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ a b Shakespeare, William (2002). Castan, David Scott (ed.). King Henry IV Part 1: Third Series, Part 1. Cengage Learning EMEA. p. 246. ISBN 9781904271345.

- ^ a b c Stone 2005, p. 68.

- ^ "Stanhope, Sir Thomas 1540-96 of Shelford". history of parliament. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ Everard Leaver Guilford (1912). "Memorials of old Nottinghamshire" (Memorials of old Nottinghamshire. ed.). London: G. Allen. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Get-a-map online". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Littleborough". Trentvale.co.uk. Retrieved 7 April 2013. Cite error: The named reference "littleb" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Owston Ferry". isleofaxholme.net. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ "West Butterwick". The Isle of Axholme Family History Society. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ "East Stockwith". Lincolnshire.gov. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d "River Trent Catchment Flood Management Plan Chapter 2" (PDF). Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ "Environment Agency What's in your Backyard". Environment-agency.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ "Highs and Lows of the East Midlands". BBC. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ "28009 - Trent at Colwick". The National River Flow Archive. Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ a b c "River Trent Catchment Flood Management Plan Chapter 3" (PDF). Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Rivers of Europe by Klement Tockner, Urs Uehlinger, Christopher T. Robinson (2009), Academic Press, London.

- ^ "Trent Valley IDB - General". naidb.co.uk. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ a b British Geological Survey. "Geology of Britain map". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 25 August 2013. - Zoomable map - click for the bedrock and superficial geologies.

- ^ a b c "Geological Evolution of Central England with reference to the Trent Basin and its Landscapes". nora.nerc.ac.uk. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ Mills, Alexander (2003). Dictionary of British Place names. Oxford University Press. p. 570. ISBN 9780191578472.

- ^ a b "Geology of the Etwall Area". nora.nerc.ac.uk. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ a b "River Trent: Archaeology and Landscape of the Ice Age" (PDF). Archaeology Data Service. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ "The Lower and Middle Palaeolithic Occupation of the Middle and Lower Trent Catchment and Adjacent Areas, as Recorded in the River Gravels used as Aggregate Resources" (PDF). BGS. 2004. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "The Humberhead Levels Natural Area" (PDF). naturalengland.org.uk. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ "River Trent Catchment Flood Management Plan Chapter 2 Part1" (PDF). Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Brown, A.G. (2008). "Geoarchaeology, the four dimensional (4D) fluvial matrix and climatic causality". sciencedirect.com. p. 285. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Midlands Climate-Rainfall". Met Office. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "River Trent Catchment Flood Management Plan Scoping Report, Part 5" (PDF). Environment Agency. p. 34. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ "28095-Tame at Hopwas Bridge Spatial Data Rainfall". The National River Flow Archive. Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ "Trent Facts". On Trent. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Climate tables UK 1961-90". Met Office. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Climate tables Climate region:England 1961-90". Met Office. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ a b Embleton, C (1997). Geomorphological Hazards of Europe. Elsevier. p. 183. ISBN 9780080532486.

- ^ a b "Hi flows – UK AMAX Data for: Trent at Colwick (28009)". Environment Agency. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Trent valley geology and flooding" (PDF). Mercian Geologist. emgs.org.uk. 2001. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ a b "1947 U.K. River Floods:60-Year Retrospective". rms.com. p. 3. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Rodda, John; Marsh, Terry (2011). The 1975-76 Drought - a contemporary and retrospective review (PDF). Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-906698-24-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Marsh, T J; Hannaford, J (2008). UK Hydrometric Register. Hydrological data UK series. Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. p. 66-67.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Annual Maximum Data for: Trent at Stoke (28040)". Peak Flow Data (HiFlows UK). Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ "Hi Flows UK AMAX Data for: Trent at Great Haywood (28006)". Environment-agency.gov.uk. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ "Hi Flows UK AMAX Data for: Trent at Yoxall (28012)". Environment-agency.gov.uk. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ "Hi Flows UK AMAX Data for: Trent at Drakelow (28019)". Environment-agency.gov.uk. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ "Hi Flows UK AMAX Data for: Trent at Shardlow (28007)". Environment-agency.gov.uk. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ "Hi Flows UK AMAX Data for: Trent at North Muskham (28022)". Environment-agency.gov.uk. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ "National River Flow Archive - Map". Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ "Chapter 8: Works in the River". Fluvial Design Guide. Environment Agency. p. 8-4. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ a b c "Colwick". Sage – Rivers Discharge Database. sage.wisc.edu. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ Davie, Tim (2008). Fundamentals of Hydrology. Taylor & Francis. p. 173. ISBN 9780415399869.

- ^ Gardiner, John (2000). The Changing Geography of the United Kingdom. Routledge. p. 357. ISBN 9780415179010.

- ^ "Willington C Gas Pipeline Environmental Statement, Volume 1, Chapter 7, Hydrology, Hydrogeology and Flood Risk Assessment" (PDF). rwe.com. p. 20. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ The Douna Hydrometric Station is located at 13°12′50″N 5°54′11″W / 13.213853°N 5.903105°W near the bridge over the river carrying the RN6 highway from Ségou to Bla.

- ^ Data from UNH/GRDC Composite Runoff Fields V 1.0.

- ^ "Alluvial Archaeology in the Vale of York". yorkarchaeology.co.uk. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "Chesterfield Canal Trust History of the Restoration". chesterfield-canal-trust.org.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Richardson, Christine; Lower, John (2008). Chesterfield Canal. Richlow. p. 10. ISBN 9780955260940.

- ^ a b "Nottingham Left Bank Flood Alleviation Scheme Flood Risk Assessment" (PDF). broxtowe.gov.uk. 2001. p. 7. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Macdonald, Neil (2012). "Reassessing flood frequency for the River Trent through the inclusion of historical flood information since AD1320" (PDF). cost-floodfreq.eu. p. 3. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ a b Brown, A.G.; Cooper, L; Salisbury, C.R.; Smith, D.N. (2001). "Late Holocene channel changes of the Middle Trent: channel response to a thousand-year flood record". Geomorphology. 39 (1). Elsevier: 69–82. Bibcode:2001Geomo..39...69B. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(01)00052-6.

- ^ "Ridware study group". High Bridge crossing. Ridware history society. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "Swarkestone" (PDF). Conservation Area Histories. South Derbyshire District Council. p. 1. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ^ "County floods remembered by Nottinghamshire Archives and Picture the Past". Press Releases. Nottinghamshire County Council. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Upper Witham IDB History". upperwitham-idb.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Stone 2005, p. 59,62

- ^ Williams, Frederick Smeeton (2012). The Midland Railway: Its Rise and Progress: A Narrative of Modern Enterprise 1876. Cambridge University Press. p. 329. ISBN 9781108050364.

- ^ a b "Nottingham Left Bank Scheme". Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b Met Office, The winter of 1946/47, retrieved 11 June 2013

- ^ "Flood Risk Assessment" (PDF). west lindsey.gov.uk. 2012. p. 5. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Hull and north Lincolnshire floods clean-up begins". BBC News Humberside. BBC. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "East Staffordshire Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Level 1 Report" (PDF). eaststaffsbc.gov.uk. 2008. p. 17. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ a b Hadfield 1985, pp. 15–17

- ^ a b c Cumberlidge 1998, p. 230

- ^ a b c Hadfield 1970, pp. 42–46

- ^ Owen 1978, pp. 13–20.

- ^ a b c UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Hadfield 1970, pp. 74–78

- ^ a b c d e Hadfield 1970, pp. 198–207

- ^ British Waterways, River Trent Water Freight Feasibility Study, p11, accessed 9 January 2010

- ^ Nicholson 2006, p. 128.

- ^ "Some Advice To Skippers using the River Trent". hnbc.org.uk. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ NGIA (2006). Prostar Sailing Directions 2006 North Sea Enroute. ProStar Publications. p. 53. ISBN 9781577857549.

- ^ "Ports and wharves of North Lincolnshire". northlincs.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "MAIB Search Results Mithril". maib.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "MAIB Search Results Maria". maib.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Freighter-Celtic-Endeavor-aground-and-refloated". news.odin.tc. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ Stone 2005, p. 9, 124.

- ^ "Justices in Eyre 1509-1840". Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ "'Norroy King of Arms', Survey of London Monograph 16: College of Arms, Queen Victoria Street (1963), pp. 101-118". British History Online. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ "'Clarenceux King of Arms', Survey of London Monograph 16: College of Arms, Queen Victoria Street (1963), pp. 74-101". British History Online. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ The Travellers' Dictionary of Quotations: Who Said What, about Where?, Peter Yapp, p372, 1983, ISBN 9780710009920, accessed 1 April 2013

- ^ "Cyanide sparks River Trent pollution probe" independent.co.uk, accessed 8 October 2009

- ^ a b c Stone 2005, p. 14, 15

- ^ "Transport on the River Trent". humberpacketboats.co.uk. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Glover, Stephen (1829). The History of the County of Derby. Mozley. p. 259.

- ^ The Statutes at Large: Volume 14. 1786. pp. 339–340.

- ^ Campbell, Bruce (2006). England on the Eve of the Black Death. Manchester University Press. p. 300. ISBN 9780719037689.

- ^ Brown, Anthony (2008). "Late Holocene channel changes of the Middle Trent: channel response to a thousand-year flood record". sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Cavendish Bridge Conservation Area Appraisal and Study" (PDF). North West Leicestershire council. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ Barber, J (1834). History of the County of Lincoln: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time, Volume 2.

- ^ Nigel J. Tringham (Editor) (2003). "Burton-upon-Trent: Communications". A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 9: Burton-upon-Trent. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Burton-upon-Trent Local History". Ferry Bridge the Ferry. burton-on-trent.org.uk. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Stone 2005, p. 69

- ^ "Willington Bridge". Willington Local History Group. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "Dunham Bridge – Homepage". Dunham Bridge Company. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d Stone 2005, p. 121,122

- ^ Carr, Michael (1997). New Patterns: Process and Change in Human Geography. Nelson Thornes. pp. 389–390. ISBN 9780174386810.

- ^ "Coal-Fired Power Plants in East England & the Midlands". Power Plants around the World. industcard.com. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ "Location to Power Stations". Modern Mining. UK Coal. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ "Our Customers". Modern Mining. UK Coal. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ "Our Operations". infinis.com. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ "River Trent". canalrivertrust.org.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Strategic Priorities for Water Related Recreation in the Midlands". brighton.ac.uk. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "Trent Valley Way". ldwa.org.uk. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Trent Valley Way". On Trent. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "TVW Feasibility Report" (PDF). On Trent. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Trent Valley Way new route confirmed". trentvale.co.uk. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Nigel J. Tringham (Editor) (2003). "Burton-upon-Trent: Social and cultural activities". A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 9: Burton-upon-Trent. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "An itinerary of Nottingham: Trent Bridge". Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 29 (1925). nottshistory.org.uk. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "Colwick Park Lifeguards – About Us". thelifeguards.org.uk. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "Burton Leander Rowing". burtonleander.co.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Newark Rowing Club". newarkrowingclub.co.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Nottingham Union Rowing Club". nurc.co.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "National Water Sports Centre – About Us". nwscnotts.com. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ British Canoe Union (2003). English White Water: The British Canoe Union Guidebook. Pesda. ISBN 9780953195671.

- ^ "Canoe Trails - Midlands". canoe-england.org.uk. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Burton Canoe Club". burtoncanoeclub.co.uk. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Stafford and Stone Canoe Club". satffordandstonecc.co.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Holme Pierrepont Canoe Club". hppcc.co.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Nottinghamshire Sailing & Yacht Clubs". Go-sail.co.uk. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Report on the investigation of Nottingham Princess striking Trent Bridge Nottingham" (PDF). maib.gov.uk. 2003. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ^ "St John Ambulance Waterwing". sja.org.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Faerie Queene. Book IV. Canto XI". spenserians.cath.vt.edu. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Water Framework Directive Surface Water Classification Status and Objectives 2012 csv file". Environment Agency.gov.uk. 26th Nov 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "National River Flow Archive". Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. Retrieved 7 May 2013.