User:Lockheed100/sandbox

Space exploration technologies is about the ideas, technologies, and programs that will enable the affordable movement of people and goods throughout the solar system and will allow mankind to begin the process of developing and colonizing space.

Space elevators and skyhooks[edit]

The generic term space elevators (plural) refers to a group of three proposed space transportation concepts that their promoters claim will make Earth-to-orbit and interplanetary spaceflight affordable, thereby opening the way for the commercial development of lunar mining, asteroid mining, space-based solar power stations, space colonies, and colonies on the Moon, Mars, and in the asteroids.

These three concepts are:

- a non-rotating Earth surface to geostationary orbit space elevator as described by Arthur C. Clarke in his book The Fountains of Paradise,

- a low Earth orbit non-rotating space elevator that does not reach down to the surface of the Earth (as described in section 3.2.1 of [1]) that is usually referred to as a non-rotating skyhook,

- and a low Earth orbit rotating space elevator that also does not reach down to the surface of the Earth (as described on pages 2-4 of [2]) that is usually referred to as a rotating skyhook.

All three of these concepts have advantages and disadvantages. The most significant of them being:

- the rotating and non-rotating skyhooks can be built with currently existing materials and technology while the Earth surface to geostationary orbit space elevator cannot,

- the rotating and non-rotating skyhooks require a suborbital launch vehicle to get the lower end of the tether while the Earth surface to geostationary orbit space elevator does not, and

- the rotating and non-rotating skyhooks require either an electrodynamic or an ion propulsion system for altitude control while the Earth surface to geostationary orbit space elevator does not.

Of these three items the most important to remember is that both the rotating and non-rotating skyhooks can be built with commercially available materials while the Earth surface to geostationary orbit space elevator cannot,[2][3][4][5][6][7]

The following is a direct quote from "Space Elevators, An Advanced Earth-Space Infrastructure for the New Millennium", a NASA Conference Paper on all three space elevator concepts that was published in the year 2000.[1]

"The LEO space elevator [non-rotating skyhook] is an intermediate version of the Earth surface to GEO space elevator concept, and appears to be feasible today using existing high-strength materials and space technology."

The following is a direct quote from "Hypersonic Airplane Space Tether Orbital Launch System" (HASTOL), a NASA funded study on rotating skyhooks.[2]

"The fundamental conclusion of the Phase I HASTOL study effort is that the concept is technically feasible. We have evaluated a number of alternate system configurations that will allow hypersonic air-breathing vehicle technologies to be combined with orbiting, spinning space tether technologies to provide a method of moving payloads from the surface of the Earth into Earth orbit. For more than one HASTOL architecture concept, we have developed a design solution using existing, or near-term technologies. We expect that a number of the other HASTOL architecture concepts will prove similarly technically feasible when subjected to detailed design studies. The systems are completely reusable and have the potential of drastically reducing the cost of Earth-to-orbit space access."

The following is a quote from Keith Henson, co-founder of the L-5 Society regarding the Earth surface to geostationary orbit space elevator.[3]

"No current material exists with sufficiently high tensile strength and sufficiently low density out of which we could construct the cable. There’s nothing in sight that’s strong enough to do it – not even carbon nanotubes."

While no skyhook capable of capturing an arriving spacecraft has been built so far, there have been a number of flight experiments exploring various aspects of the skyhook/space tether concept.[8]

Affordable spaceflight and skyhooks[edit]

The three most important issues that need to be addressed if a transportation system is to be commercially affordable on a mass-market level are:

- reusability,

- a low propellant fraction, and

- a high payload fraction.

Reusability so the investment can be amortized over a large number of trips, a low propellant fraction for reduced operating costs, and a large payload fraction so that the cost of each trip can be distributed over a large amount of payload. Trains, planes, automobiles, trucks, and ships are all very good examples of this. Currently existing expendable rockets are not.

When a launch vehicle takes-off to go to Earth orbit, approximately 90% of its take-off weight is propellant, 9% is the weight of the rocket, and 1% is the weight of the payload.[9] With numbers like these it should be fairly obvious why the currently existing expendable launch vehicles are somewhat of a failure when it comes to meeting the three main requirements for a commercially affordable mass-market transportation system. This is also why current launch vehicles cost so much.

The reasons for this failure are threefold:

- the speed the rocket needs to achieve to reach Earth orbit,

- the amount of propellant it takes to achieve that speed (which has to do with the performance of the rocket motor), and

- the lack of reusability of the launch vehicle.

The total speed that a launch vehicle needs to achieve in order to reach low Earth orbit is approximately 9,400 m/s. This includes the speed of low Earth orbit, plus additional velocity for overcoming the force of gravity that is trying to pull the rocket down, and additional velocity for the atmospheric drag as the launch vehicle climbs through the atmosphere.

A skyhook makes spaceflight affordable by reducing the speed the rocket needs to achieve in order to reach low Earth orbit. That reduction in speed means less propellant is required. The reduction in propellant allows the size of the payload to be increased. More payload and less propellant per flight means a lower cost to orbit.

In order to provide some examples of how different sized reductions in velocity translate into increased payload capacity, some simple calculations were made using the ideal rocket equation, the 90% propellant, 9% rocket, and 1% payload ratio, and the 9,400 m/s total speed for orbit value. The results of these calculations show that:

- reducing the speed required for orbit by 200 m/s increases the payload size by over 50% and reduces the cost by over 33%,

- reducing the speed required for orbit by 400 m/s more than doubles the size of the payload and reduces the cost by over 50%,

- reducing the speed required for orbit by 800 m/s more than triples the size of the payload and reduces the cost by over 67%,

- reducing the speed required for orbit by 1,600 m/s increases the payload by a factor of 6 and reduces the cost by over 84%.

This process continues as the skyhook gets longer and applies to both rotating and non-rotating skyhooks.

Reusability of the launch vehicle is the third key issue that needs to be addressed if a skyhook space transportation system is to become commercially affordable on a mass-market level. Using some of the increased payload capacity that the skyhook makes possible to make the launch vehicle reusable is an idea that is used and discussed in every reference in this article that discusses either rotating or non-rotating skyhooks. The specific amount of extra weight that will be required to make a launch vehicle reusable will depend on the details of the launch vehicle design. Is it single-stage-to-orbit, two-stage-to-orbit, ground launched, air launched, catapult launched, air-breathing, all rocket, or a combination propulsion system? All of these will have different requirements in order to make the launch vehicle reusable. But regardless of the details, using some of the increased payload capacity made possible by the skyhook to go from an expendable launch vehicle to a reusable launch vehicle, will also be a very important step in the process of making spaceflight mass-market affordable: which is the whole purpose of a skyhook.

Non-rotating skyhooks[edit]

A non-rotating skyhook is a vertically oriented, gravity gradient stabilized tether whose lower endpoint does not reach the surface of the planet it is orbiting. As a result it appears to be hanging from the sky, hence the name skyhook. The idea of using a tidally stabilized tether for downward-looking Earth observation satellites was first proposed by the Italian scientist Giuseppe Colombo.[10]

The idea of using a non-rotating skyhook as part of a space transportation system for Earth where sub-orbital launch vehicles would fly to the bottom end of the tether, and spacecraft bound for higher orbit, or returning from higher orbit, would use the upper end of the tether, was first proposed by E. Sarmont in 1990,[9] expanded on in a second paper in 1994,[11] and in a third paper in 2014.[12] Other scientists and engineers, as well as NASA, Lockheed Martin, former astronaut Bruce McCandless II, and Dr. Robert Zubrin, have also investigated, validated, and added to this concept.[13][1][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21]

In addition, NASA representatives who have reviewed this concept have described it as, "The first idea we have seen that offers a believable path to $100 per pound to orbit."[22]

Conceptually the main difference between a non-rotating skyhook and an Earth surface to geostationary orbit space elevator is that the non-rotating skyhook does not reach down to the surface of the Earth. The lower end of the non-rotating skyhook is above the upper edge of the atmosphere and requires a high-speed aircraft/sub-orbital launch vehicle to get there. Since the lower end of the skyhook is moving at less than orbital velocity for its altitude, a launch vehicle flying there can carry a larger payload than it could carry to orbit on its own.[13] When the cable is long enough, single-stage to skyhook flight with a reusable sub-orbital launch vehicle becomes possible.[1] In addition, unlike a space elevator that remains over the same spot on the Earth, a non-rotating skyhook circles the planet every few hours. This allows the skyhook to serve as a terminal for sub-orbital launch vehicles arriving from just about anywhere on Earth. This type of skyhook can start out as short as 200 km and grow to over 4,000 km in length using a bootstrap method that takes advantage of the reduction in launch costs that come with each increase in tether length.

At its longest, the non-rotating skyhook is approximately 1/25th the length of the 100,000 km long space elevator. As a result, it is much lighter in mass, and can be affordably built with existing commercially available carbon fiber materials.[1] Analysis has also shown that this saving in construction cost for the non-rotating skyhook more than makes up for the additional cost of the sub-orbital launch vehicle that it requires. As a result, a mature non-rotating skyhook with reusable single stage sub-orbital launch vehicle is considered to be cost competitive with what is thought to be realistically achievable using a space elevator,[11] assuming a space elevator can ever be built.[3][4][5][6][7]

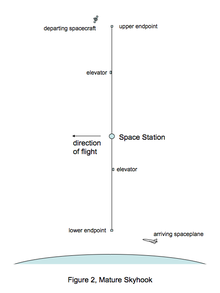

Another advantage of the non-rotating skyhook is that once it is long enough, the upper end of the cable as shown in figure 2, will be moving at just short of escape velocity for its altitude. This means that a spacecraft such as the Orion spacecraft could be placed on either a free-return orbit to the Moon, or on course for a near-Earth asteroid, without the need for an expensive expendable upper stage for boosting it to escape velocity.[10][11][1] Elimination of the expendable upper stage and all the propellant it will require will also dramatically reduce the number of flights to the lower end of the non-rotating skyhook, which will further reduce the cost of such a mission.

This ability to capture sub-orbital launch vehicles coming up from the Earth at the lower end of the cable, and to launch spacecraft to higher orbits from the upper end of the cable, requires energy. Energy that comes from either a solar powered ion propulsion system[23] or an electrodynamic propulsion system on the skyhook. The advantage of this over current launch systems is the greatly improved operating efficiency and reduced cost of either of these propulsion systems compared to conventional expendable rockets.[11][24] While these high-efficiency, low-thrust propulsion systems cannot be used for a planetary surface to orbit launch system due to their low thrust, they are perfect for use on an orbiting skyhook due to their ability to gradually store up energy by raising the orbital altitude of the skyhook between arriving and departing flights.

The docking maneuver[edit]

The process of docking an arriving spacecraft at the lower end of the non-rotating skyhook starts with the skyhook in an elliptical orbit. The low point of this elliptical orbit, the perigee, is selected so that the lower end of the skyhook cable will be at an altitude of 185 km at that point in the orbit. The altitude of the high point of the elliptical orbit, the apogee, is selected based on the mass of the arriving spacecraft.

In addition to boosting the arriving spacecraft to the proper speed and altitude for rendezvous, the sub-orbital launch vehicle for this flight will also need to time its take-off so that it will rendezvous with the lower end of the skyhook when the skyhook is at the low point of its orbit.

When the arriving spacecraft docks with the lower end of the skyhook it will lower the center of gravity of the total skyhook system, thereby pulling the skyhook down into a lower more circular orbit. If the apogee altitude of the skyhook's initial elliptical orbit was properly selected, the skyhook will end up in a circular orbit after the arriving spacecraft has docked.

Upon completion of the docking maneuver, the skyhook's solar-powered ion propulsion system, or electrodynamic propulsion system, is activated so as to start raising the orbital altitude of the skyhook back to its original altitude.

What makes the skyhook concept work is energy exchange. When the skyhook is in its initial elliptical orbit it is in a higher-energy orbit than the one it ends up in after the arriving spacecraft docks with the lower end of the skyhook. What happens is that the skyhook gives the extra energy of the higher elliptical orbit to the arriving sub-orbital spacecraft; a spacecraft that doesn't have enough energy to remain in orbit on its own. The end result is that the arriving spacecraft gets an energy boost from the skyhook that allows it to remain in orbit while the skyhook gives up energy and drops to a lower energy orbit. Before another arriving spacecraft can dock at the lower end of the skyhook, the skyhook will need to use its high efficiency low thrust propulsion system to raise itself back to the original higher-energy orbit.

The Upper End of the Skyhook[edit]

The upper end of a mature Skyhook is designed to be moving at slightly less than escape velocity for its altitude. What that means is that a spacecraft departing from the upper end of the Skyhook can, with the use of only a very small amount of onboard propellant, be headed for geosynchronous orbit, on a free return trajectory to the Moon, on its way to one of the Lagrange Points, or headed for a Near Earth Asteroid. To put this in perspective, consider the Saturn V rocket that was used to fly to the Moon in the late '60s and early '70s. The Saturn V had a take-off weight of 6,200,000 pounds. Its payload to low Earth orbit was 260,000 pounds. Its useful payload to Earth escape velocity was 100,000 pounds. Everything else, 6,100,000 pounds worth, was used up and thrown away. Now compare this to a mature Skyhook launch system.

A passenger leaves Earth on a highly reusable suborbital spaceplane that takes off from an airport and flies to the bottom end of the Skyhook. The passenger transfers from the spaceplane to the Skyhook and the spaceplane returns to Earth with a load of returning passengers and cargo. The next step in the journey is a ride on the elevator up the tether to the space station in the middle of the Skyhook where a transfer is made to another elevator that is bound for the upper endpoint. Nothing is thrown away, everything is reusable. At the upper endpoint station the passenger transfers to a small reusable Earth-Moon spacecraft that is similar to the Apollo Command/Service Module, which will take him/her to lunar orbit. The Earth-Moon spacecraft will use a very small amount of onboard rocket propellant when it departs the Skyhook, and will then fire its rocket motor a second time to slow down to lunar orbit velocity when it arrives at the Moon. Upon arrival in lunar orbit, the Earth-Moon spacecraft will rendezvous and dock with a reusable single stage Lunar Lander that is carrying passengers and cargo bound for Earth plus additional rocket propellant for the Earth-Moon spacecraft. After the passenger, cargo, and propellant exchange is complete, the Lunar Lander leaves lunar orbit and descends to the surface of the Moon. Again, everything is reusable, nothing is thrown away, and the rocket propellant for the Lunar Lander and the Earth-Moon spacecraft comes from the Moon.

NASA is currently funding the development of a reusable Earth-Moon/Earth-Asteroid spacecraft that is similar to an Apollo Command/Service Module called the Orion spacecraft. Combine this with a Skyhook and we will have an affordable transportation system for traveling to Lunar orbit, the Earth/Moon Lagrange points, and the near Earth asteroids. Add a single stage reusable Lunar Lander and we will have an affordable transportation system for going to the Lunar surface. With access to Lunar and/or near Earth asteroid materials, the building of a large, well shielded, rotating, Mars cycler spacecraft, or Ion powered Earth-Mars spacecraft, becomes possible, and safe regular affordable interplanetary spaceflight to Mars, the Moons of Mars, as well as Ceres and all the other asteroids between Mars and Jupiter, becomes possible.

Patents[edit]

In the year 2000, Dr. Robert Raymond Boyd and Dimitri David Thomas (with Lockheed Martin Corporation) applied for a patent on the non-rotating Skyhook concept under the name "Space elevator". They were granted a patent on this concept in 2002. [6].

Critics of this patent question its legality due to the existence of published materials on the non-rotating Skyhook concept that pre-date the patent by 10 years.

A non-rotating skyhook transportation system for Mars[edit]

In 1984, Paul Penzo of JPL proposed a planetary surface to escape velocity tether transportation system for Mars that consists of two non-rotating skyhooks; one attached to the Martian moon Phobos, and the other attached to the Martian moon Deimos.[25][26]

With this system, a spacecraft arriving at Mars, either direct from Earth, or from an Earth-Mars cycler spacecraft as it swings by Mars, docks at the upper end of the non-rotating skyhook attached to the outer moon Deimos. The people and cargo on that spacecraft then transfer to an elevator on the skyhook that will take them down to the lower end of the Deimos skyhook. There they board a small orbital transfer vehicle that will take them to the upper end of the non-rotating skyhook that is attached to the inner moon Phobos. Again they transfer to an elevator that will take them to the lower end of the Phobos skyhook where they will transfer to the reusable single stage Mars Lander that will carry them to the Martian surface. Passengers and cargo from the Martian surface that are bound for either the asteroids, or for Earth, would ride the system in reverse.

One of the advantages of this concept is that neither skyhook will require a propulsion system for orbital re-boost or for orbit control, as they both will use the Martian moon they are attached to as a momentum bank to make up any discrepancies in the upward versus downward mass flow of people and cargo. This elimination of the propulsion systems for the two skyhooks also makes for a significant reduction in the cost to build, and the cost to operate. Like the non-rotating skyhook for Earth, this two-stage non-rotating skyhook system for Mars can be affordably built with existing materials and technology.

Advantages and disadvantages of a non-rotating skyhook versus a rotating skyhook[edit]

- the non-rotating skyhook has a much larger rendezvous window for arriving launch vehicles and spacecraft than the rotating skyhook which makes for a much safer, more reliable, and easier to use system,

- the non-rotating skyhook allows for the separation of arrival and departure operations at the lower end of the cable from the arrival and departure operations at the upper end of the cable which adds significantly to the operational flexibility of the system,

- when the non-rotating skyhook is long enough and the lower endpoint velocity is low enough, single stage to skyhook flight with a reusable sub-orbital launch vehicle becomes possible.

Rotating skyhooks[edit]

As the name implies, rotating skyhooks rotate end over end in the plane of their orbit such that the upper endpoint becomes the lower endpoint and the lower endpoint becomes the upper endpoint. In other words, it rotates like a wheel that has two spokes and no rim.

The Earth Launch Assist Bolo or Hypersonic Skyhook[edit]

When a rotating skyhook is placed in orbit around a planet, the rotational direction is selected so that the lower endpoint of the skyhook is moving slower than orbital velocity and the upper endpoint is moving faster than orbital velocity. When the planet being orbited has an atmosphere, the length and orbital altitude of the rotating skyhook is selected so that the lower end of the cable is above the majority of the atmosphere when it is closest to the ground.[2] The reasons for this are to minimize heating of the cable as it passes through the upper part of the atmosphere, and so that a launch vehicle flying to the bottom end of the rotating skyhook does not have to deal with atmospheric buffeting while attempting to dock with the lower end of the skyhook. The fact that the lower end of the cable has a horizontal velocity of less than orbital velocity means that the launch vehicle will not have to go as fast as it would if it were going directly to orbit. Therefore, like the non-rotating skyhook, this reduction in velocity increases the payload capacity of the launch vehicle, thereby reducing the cost of getting into orbit. Once the payload in the suborbital launch vehicle is captured by the lower end of the rotating skyhook, it is carried up and around until the end of the cable is at the top of its rotational arc where the payload is released. When released, the payload will be moving faster than circular orbit velocity for that altitude.[27] This rotating skyhook/sub-orbital launch vehicle combination has also been referred to as 'Tether Launch Assist'.[28]

Like the non-rotating skyhook, the rotating skyhook known as an 'Earth launch assist bolo':

- will need to be in a higher energy elliptical orbit prior to picking up the payload from an arriving launch vehicle

- will need a solar powered ion propulsion system, or electrodynamic propulsion system, for re-boosting the rotating skyhook back to its original orbit after lifting the arriving payload to a higher orbit

- will need to be at the low point of its elliptical orbit when the payload pickup is made

- will need a sub-orbital launch vehicle for carrying cargo and passengers to and from the lower end of the cable.

In addition, the rotational position of the lower end of the cable will also need to be at the bottom of its swing when the rotating 'Earth launch assist bolo' is at the low point of its elliptical orbit.

The Release Orbit. The primary purpose of a Skyhook is to reduce the velocity required for orbit so as to increase the launch vehicle's payload and thereby reduce the cost of getting into orbit. The greater the velocity reduction, the greater the cost reduction.

With a rotating Skyhook, the greater the amount of velocity reduction at the lower end, the greater the amount of excess velocity at the upper end. In other words, if the rotating cable is moving at 90 percent of circular orbit velocity for that altitude at the bottom of its swing, it will be moving at more than 110 percent of circular orbit velocity at the release point at the top of its swing. If the destination orbit of the spacecraft being lifted is higher than that - wonderful. However, if the destination orbit is lower, then the spacecraft will need to use its onboard propulsion system to slow down to get there. Obviously, a somewhat counter productive situation.

Unfortunately, the problem only gets worse as the velocity reduction at the bottom gets larger. For example, when the length of the hypersonic Skyhook has grown so that the lower end is moving at 60 percent of circular orbit velocity for its altitude, the release velocity at the upper end will be in excess of escape velocity. In other words, any spacecraft that desires to remain in Earth orbit will need to use its onboard propulsion system to slow down in order to stay in orbit.

This also causes a problem for interplanetary bound spacecraft. Interplanetary travel requires both high velocity and precise course control. In order for a spacecraft to go directly from high speed suborbital flight to escape velocity, the launch will need to be timed not just for the Skyhook cable being at the bottom of its swing, and the Skyhook being at the low point of its baseline elliptical orbit, it will also need to be timed and positioned so that the release orbit will put the spacecraft on the necessary flight path for its destination. Combining all these requirements together in one operation increases the operational complexity of the flight to such a degree that success becomes very questionable.

Rendezvous and capture. The following is direct quote from "Hypersonic Airplane Space Tether Orbital Launch System" (HASTOL).[2]

"In any rotating tether transport system, one of the most challenging tasks will be to enable the rendezvous between the payload and the tether tip. For the tether to successfully capture the payload, the payload and tether grapple vehicle must come together at nearly the same place in space and time with nearly the same velocity. Because the payload is in free fall, and the tether is rotating, the payload and grapple vehicle will experience a relative acceleration equal to

a = Vt2/L

where Vt is the velocity of the tether tip relative to the tether facility’s center of mass, and L is the distance from the tether tip to the center of mass. In the HASTOL tether designs described above, Vt is approximately 3.5 km/s, and L is approximately 500 km, so this acceleration is about 2.5 g’s. If neither grapple nor payload perform any maneuvering, the two will coincide only instantaneously, providing a minimal rendezvous window. Fortunately, it is possible to extend this rendezvous window to five seconds or more by using tether deployment from the grapple vehicle."

The rendezvous and capture of a payload at the lower end of a rotating skyhook happens in five seconds or it does not happen. Compare this to the three to five minutes that are available for rendezvous and capture with the non-rotating skyhook.[10] When using a reusable launch vehicle to fly to the bottom of either a rotating or non-rotating skyhook, a missed approach does not mean the loss of a launch vehicle or payload. However, it does mean that the mission will need to be re-flown with all the additional cost that entails. As a result, critics of the rotating skyhook concept are concerned, that due to the much shorter amount of time available for rendezvous and capture, that the rotating skyhook will likely have a much higher re-flight rate than the non-rotating skyhook. This is an additional cost that will need to be accounted for when comparing the two concepts. Fortunately this is an issue that NASA Marshall Space Flight Center and Tennessee Technological University have been working on.[29]

Advantages and disadvantages of a rotating skyhook versus a non-rotating skyhook[edit]

- the overall length of a rotating skyhook is shorter than a non-rotating skyhook for a given lower endpoint velocity thereby allowing for a lighter weight tether,

- the much shorter rendezvous window for arriving launch vehicles at the lower end of the rotating skyhook significantly increases the likelihood of a missed approach,

- the rotating skyhook unavoidably links the upper end departure operation with the lower end arrival operation which severely limits the usability of the system when traveling to a higher orbit or to other planets,

- when the lower endpoint velocity of the rotating skyhook is low enough, single stage to skyhook flight with a reusable sub-orbital launch vehicle becomes possible.

Zero velocity rotating skyhooks[edit]

Another proposed method for using a rotating skyhook that is in orbit around a small airless, or near airless body such as the Moon or Mars, is to select the length and rotation rate of the skyhook such that the lower end of the cable would have zero horizontal velocity relative to the ground so that it could pick up payloads directly from the planetary surface. These type of rotating skyhooks are called non-synchronous skyhooks, rotovators, or zero velocity rotating skyhooks.

Interplanetary skyhooks[edit]

A third type of rotating skyhook is one that is far from its parent body, that rotates in the plane of the planets, and is used for interplanetary spaceflight. An example of this would be a rotating skyhook located at L-4, the leading Earth-Moon Lagrangian point, that would be used to launch and receive small transfer spacecraft traveling to and from a Mars cycler spacecraft as it swings by the Earth on it way to Mars and the asteroid belt again. This type of rotating skyhook is sometimes referred to as a free space skyhook, bolo, interplanetary bolo, or interplanetary skyhook.

Hans Moravec[edit]

All three of these rotating skyhook concepts were first published by Dr. Hans Moravec in 1977,[30] expanded on in follow-on papers in 1978,[31][32] and again in 1986.[33] In his first paper he states that the idea for the rotating skyhook was conceived and suggested to him by John McCarthy of Stanford University.[30] Other scientists and engineers, as well as NASA, Boeing, Tethers Unlimited, Inc., Dr. Robert Forward and Dr. Robert P. Hoyt, have also investigated, validated, and added to the rotating skyhook concept.[34][35][36]

Launch vehicles[edit]

Any orbital launch vehicle can fly to the lower end of either a rotating or non-rotating skyhook, allowing it to both increase its payload capacity and reduce its launch cost compared to flying directly to orbit on its own. This applies to all existing expendable launch systems, such as the Atlas V, Delta IV, Falcon 9, Antares, Vostok, Proton, Long March, and the Ariane V.

It also applies to air launch to orbit launch systems such as the Stratolaunch/Pegasus II combination, or to proposed reusable launch systems such as the reusable Falcon 9, New Shepard, Skylon, DC-X, a vertical take-off horizontal landing rocket powered spaceplane,[37] a rocket-based combined cycle powered spaceplane,[38] or the scramjet-powered Rockwell X-30.

Additional advanced launch vehicle concepts that could also benefit from using a skyhook can be seen here.[39]

While Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo currently does not fly high enough or fast enough to reach the lower end of either a rotating or non-rotating skyhook, it does provide an idea what space flight to a skyhook might look like in the near future.

Combination launch systems[edit]

In 1999, in the workshop that lead to the NASA conference paper "Space Elevators, An Advanced Earth-Space Infrastructure for the New Millennium",[1] the idea of combining some kind of ground accelerator, rocket sled, or catapult with a non-rotating skyhook was proposed as a way of further reducing the propellant fraction of the sub-orbital launch vehicle so as to increase its payload fraction and further reduce the cost of getting to orbit.

In 2009, Dr. Dana Andrews of the University of Washington, went into more detail regarding a possible combination non-rotating skyhook and catapult system in pages 6 through 12 of a presentation he gave at the 'Advanced Space Technology Workshop' at NASA Langley.[20] In addition to the catapult further reducing the propellant fraction of the sub-orbital launch vehicle, another way of taking advantage of this combination system would be to use it to reduce the startup cost of building an initial skyhook system by off-loading some of the launch vehicle velocity reduction to a cheaper to build ground accelerator which then allows for a shorter and less expensive skyhook in the beginning. The trackless ground accelerator shown in this presentation, which builds on the winch launch system used by sailplanes, is potentially one very low cost method for doing this. Another possible low cost ground accelerator idea for use with a skyhook would be a rail system like the Holloman High Speed Test Track which currently holds the land speed record for rail vehicles of Mach 8.6, or 9,465 ft/s (2,885 m/s).

The idea of adding some type of ground accelerator or catapult to a launch system is not new.[40] The Wright brothers used a catapult to help get the Wright Flyer up to take-off speed for its first flights. The U.S. Navy uses them to launch aircraft off of aircraft carriers on a daily basis. They have also been used in a number of science fiction stories and movies for launching spacecraft into orbit. Air launch to orbit, where an airplane is used to carry the launch vehicle up to 30,000 to 40,000 feet of altitude before launch, is another launch method that could be used as part of a combination skyhook launch system.

A recent development in the world of ground assisted launch is a project called VALT, which stands for Vertical Accelerator Launch Tower. For more information on VALT go to [41]

Best orbit for a skyhook[edit]

The two most commonly proposed orbits for either a rotating or non-rotating skyhook are the plane of the equator and the plane of the planets,[42] also known as the plane of the ecliptic.

The advantage of an equatorial orbit is that it allows for frequent revisit opportunities between a near-equatorial launch and landing site and the lower end of the skyhook. This is especially important if the ground site includes a ground accelerator or catapult for giving the sub-orbital launch vehicle its initial boost. The disadvantage of the equatorial orbit is that a spacecraft using the upper end of the skyhook for interplanetary travel will most likely require a plane change maneuver.

The advantage of the skyhook orbit being in the plane of the planets is that it avoids the need for a plane change maneuver when going interplanetary or when launching a spacecraft from the upper end of the skyhook to rendezvous with a Mars cycler as it swings by the Earth. The disadvantage of this orbit is the greatly reduced frequency of launch opportunities from a fixed ground site to the lower end of the skyhook. As a result, use of this orbit would most likely drive the design of the sub-orbital launch vehicle to an air launch to orbit system like Stratolaunch but with a single stage reusable launch vehicle.

[edit]

Navigating a skyhook and controlling the location of the low point of its orbit, its orbital eccentricity, and its average orbital altitude will be very different from any other Earth orbiting satellite or spacecraft that has been put in orbit before. The primary difference between a skyhook and previous orbital vehicles is that the skyhook will be under almost continuous acceleration and as a result its perigee location, eccentricity, and average altitude will be in a near-constant state of change. This applies to both rotating and non-rotating skyhooks regardless of their overall length and inclination of orbit. For a skyhook in an orbit that is inclined to the plane of the equator there will also be the additional issue of nodal precession and how to manage the change in the orbital plane this causes so that the skyhook will be in the desired orbital plane at the right time for launching a vehicle from the upper end of the skyhook. Another significant issue regarding the navigation of a skyhook is the low thrust to weight ratio of the skyhook propulsion system and the resulting low rate of acceleration. It is due to this low rate of acceleration that every spacecraft arrival at the lower end of the skyhook, every return to Earth from the lower end of the skyhook, and every launch to a higher orbit from the upper end will need to be planned many months in advance and coordinated with other planned arrivals, departures, and upper endpoint launches in order to make sure the skyhook is in the right place at the right time so as to fulfill each specific mission and to maximize the utilization of the skyhook.

Control of all these factors is made possible by the skyhook's propulsion system and by planning in advance so as to minimize the total change in velocity required by the skyhook to accomplish the various missions. Some of the possible control methods for accomplishing this are:

- vectoring and varying the thrust of the ion propulsion system

- pausing for a period of time in a specific orbit that has an orbital period or nodal precession rate that allows the skyhook to end up in the desired orbit at the desired time

- timing the release of refuse from the lower end of the skyhook into a re-entry orbit such that the resulting change in orbit to the skyhook assists in the navigation to the desired orbit at the desired time.

The journey to Mars and beyond[edit]

Between 1954 and 1963, the Director of NASA Marshall Space Flight Center's Space Sciences Laboratory, Ernst Stuhlinger, proposed three different Ion powered spaceships for manned expeditions to Mars.[43][44][45] The first of these concepts was solar powered, while the second and third were nuclear powered. All three of these concepts would take approximately two months to slowly accelerate out of low Earth orbit to escape velocity, and then continue accelerating in solar orbit until they were half way to Mars where they would then turn around and begin decelerating into high Mars orbit. The transfer time in solar orbit, from Earth escape velocity until arriving at high Mars orbit, was 5 months. After that they would take an additional month to slowly spiral down to low Mars orbit. Videos of two of the three Ion powered spaceships designed by Ernst Stuhlinger, the Sun Ship, and the Mars Umbrella Ship, can be seen at [46] for the Sun Ship, and [47] for the Mars Umbrella Ship.

Outpost space stations[edit]

In 1984, Paul Keaton of the Los Alamos National Laboratory wrote a paper about the need for outposts in space along the routes to the planets and other places of interest.[48] These outposts to be warehouses for propellant, spare parts and supplies, rest stations for crew members, and transshipment sites for cargo. The first outpost to be a space station in low Earth orbit. For the second outpost he proposed two possible locations; the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point, or the Earth-Moon L2 Lagrange point. Both of these locations are relatively easy to reach, and both allow the use of gravity assist maneuvers by departing spacecraft as they pass by the Moon and Earth on their way to the next outpost, Mars, or beyond. He also proposed that the third outpost be located at the Sun-Mars L1 Lagrange point where it would serve as the departure point for trips to the Martian moons, low Mars orbit, the asteroids, and return trips to Earth. Since these outpost stations will be located on the Interplanetary Transport Network they will also support the low energy transfer of equipment and supplies that can be sent ahead on an unmanned cargo vessels prior to the departure of the high speed crewed vessel.

Another one of the advantages of the outpost concept is the way it breaks up the journey into segments. For example, once both the second and third outpost stations are in place and local sources of propellant are established for each, Mars bound spacecraft that travel between these two stations will only need to carry enough propellant for a one-way trip on this segment and not for the entire round-trip journey to Mars as they would without the outpost stations. This allows the spacecraft to carry a much larger payload fraction and to be designed as a completely reusable vehicle - two features that will greatly reduce the cost of interplanetary spaceflight.

As with so many proposed space transportation concepts the question usually becomes, "How real is it?" For the outpost space station concept it is interesting to note that Nasa has funded three different design studies for the building of such an outpost at the Earth-Moon L2 Lagrange point called Deep Space Habitat, Exploration Gateway Platform, and Skylab II. Also of note, in 2011, Nasa's Technology Applications Assessment Team presented a concept for a manned deep space exploration spacecraft called Nautilus-X that would be perfect for trips departing from an Earth-Moon L2 outpost station bound for either a near Earth asteroid, Mars, or beyond. This spacecraft could be powered by either a solar powered ion propulsion system similar to that used on Ernst Stuhlinger's Sun Ship, or a nuclear electric ion propulsion system as used on his Mars Umbrella Ship. Other possible propulsion systems for this vehicle are VASIMR, a mass driver propulsion system, or existing chemical rocket motors.

Local sources of propellant[edit]

A key ingredient that the outpost stations will need to supply if they are to make interplanetary spaceflight mass market affordable will be local sources of propellant. Nasa has been working on the solution to this with it's Asteroid Redirect Mission. This is the mission that will move a small asteroid into Lunar orbit. It is this asteroid that will also be the destination of the first manned mission on the Orion spacecraft once the asteroid has arrived in Lunar orbit. For more information on this Orion mission see Exploration Mission 2. It is this asteroid redirect technology that will allow small asteroids to be moved to Outpost Station 2 at the Earth-Moon L2 Lagrange point and to Outpost Station 3 at the Sun-Mars L1 Lagrange point, and it is these asteroids that will be the local sources of propellant for Nautilus-X on its voyages of exploration around the inner solar system. It almost doesn't matter what the asteroids are made of as just about anything will work for propellant. If the asteroid has a lot of water ice the water could be made into LOX and LH2 for chemical rocket motors. Another option is to use the hydrogen for a VASIMR propulsion system. A third option would be to grind up the rocky material and use it as reaction mass with a mass driver propulsion system as proposed by Gerard K. O'Neill

In conclusion[edit]

It is interesting to think about what a near future space transportation system based on all these concepts might look like.

- a reusable suborbital launch vehicle for flying to the lower end of a Skyhook

- a Skyhook in Earth orbit

- the Orion spacecraft for manned spaceflight beyond the upper end of a Skyhook

- an outpost space station at the Earth-Moon L2 Lagrange point

- robotic asteroid retrieval spacecraft

- Lunar landers and mass drivers for moving people and cargo between the outpost station and the moon

- and Nautilus-X for voyages of exploration to the near Earth asteroids, Mars, and maybe even to the main belt asteroids.

Once this system is in place we will be able to build the third outpost space station at the Sun-Mars L1 Lagrange point, and the two non-rotating skyhooks that will be attached to the two Martian moons Phobos and Deimos. All of which will further reduce the cost of getting to Mars and will make all the dreams for the Colonization of Mars and the Terraforming of Mars into reality.

Skyhooks in fiction[edit]

- A non-rotating skyhook was constructed during the events of Jack McDevitt's novel Deepsix.

- In the anime Bubblegum Crisis: Tokyo 2040, the three main protagonists arrive at the series' climactic battle with Galatea in Earth orbit by commandeering a skyhook transit system.

- Turn-A Gundam, anime series, depicts an ancient hypersonic skyhook which has been maintained operationally by nanomachines over thousands of years. An ancient mass driver is also used for transporting space-vessels from earth's surface to the skyhook.

- In the Star Wars expanded universe, skyhooks are common above Coruscant. They are frequently private retreats owned by corporations or wealthy individuals.[citation needed]

- In the LucasArts video game Star Wars: The Force Unleashed a skyhook is being constructed on the planet Kashyyyk.

- The planet of Tara K. Harper's Grey Ones series features a number of skyhook stations. The tethers are apparently no longer functioning, but large terminal structures still exist.[citation needed]

- A skyhook figures prominently in Arthur C. Clarke's posthumous novel The Last Theorem, which he co-wrote with Frederik Pohl. The novel describes the skyhook as a means of interplanetary travel rather than simply a means to reach orbit. It is used as a means of transport by athletes and delegates to the "first-ever lunar Olympics".

- Skyhook construction is a central theme in the science fiction novel The Barsoom Project, the second book in the Dream Park series, by Larry Niven and Steven Barnes. The destructive potential of a falling skyhook is also explored, and the potential for this to be exploited by terrorists.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- Space Exploration Vehicle

- Mass driver

- Rocket sled launch

- Space dock

- Space tether

- Space tether missions

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Smitherman, D.V. "Space Elevators, An Advanced Earth-Space Infrastructure for the New Millennium". NASA/CP-2000-210429.

{{cite web}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e Bogar, Thomas J.; Bangham, Michal E.; Forward, Robert L.; Lewis, Mark J. (7 January 2000). "Hypersonic Airplane Space Tether Orbital Launch System". Research Grant No. 07600-018l Phase I Final Report (PDF). NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2005-12-18. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ a b c Dvorsky, G. (13 February 2013). "Why we'll probably never build a space elevator". io9.com.

- ^ a b Feltman, R. (7 March 2013). "Why Don't We Have Space Elevators?". Popular Mechanics.

- ^ a b Scharr, Jillian (29 May 2013). "Space Elevators On Hold At Least Until Stronger Materials Are Available, Experts Say". Huffington Post.

- ^ a b Templeton, Graham (6 March 2014). "60,000 miles up: Space elevator could be built by 2035, says new study". Extreme Tech. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

- ^ a b darnell (10 April 2009). "Are Traditional Space Elevators the Wrong Way Up?". Colony Worlds. Archived from the original on 2009-07-14.

- ^ Chen, Yi; Huang, Rui; Ren, Xianlin; He, Liping; He, Ye (2013). "History of the Tether Concept and Tether Missions: A Review". ISRN Astronomy and Astrophysics. 2013: 1–7. doi:10.1155/2013/502973.

- ^ a b Sarmont, E. (26 May 1990). An Orbiting Skyhook: Affordable Access to Space. International Space Development Conference. Anaheim California.

- ^ a b c Cosmo, M.; Lorenzini, E. (December 1997). Tethers in Space Handbook (PDF) (Third ed.). Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2003-03-22.

- ^ a b c d Sarmont, E. (October 1994). "How an Earth Orbiting Tether Makes Possible an Affordable Earth-Moon Space Transportation System". SAE 942120. SAE Technical Paper Series. 1. doi:10.4271/942120.

- ^ a b Sarmont, E. (July 2014). "Affordable Access to Space: Basic Non-Rotating Skyhook with Falcon 9 & Dragon" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Wilson, N. (August 1998). "Space Elevators, Space Hotels and Space Tourism". SpaceFuture.com.

- ^ Mottinger, T; Marshall, L (2000). "The Bridge to Space – A space access architecture". doi:10.2514/6.2000-5138. AIAA 2000-5138.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Mottinger, T; Marshall, L (2001). "The Bridge to Space Launch System". Space Technology and Applications International Forum. CP552.

- ^ Marshall, L; Ladner, D; McCandless, B (2002). "The Bridge to Space: Elevator Sizing & Performance Analysis". Space Technology and Applications International Forum. CP608.

- ^ Stasko, S; Flandro, G (2004). "The Feasibility of an Earth Orbiting Tether Propulsion System". 40th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit. doi:10.2514/6.2004-3901. ISBN 978-1-62410-037-6. AIAA 2004-3901.

- ^ Zubrin, R (September 1993). "The Hypersonic Skyhook". Analog Science Fiction / Science Fact. 113 (11): 60–70.

- ^ Zubrin, R (March 1995). "The Hypersonic Skyhook". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 48 (3): 123–128. Bibcode:1995JBIS...48..123Z.

- ^ a b Andrews, D. (3 September 2009). "Advanced ETO Space Transportation". NASA Langley Advanced Space Transportation Workshop. Archived from the original on 2014-07-13.

- ^ Andrews, D. "Space Colonization: A Study of Supply and Demand" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-03-11.

- ^ Sarmont, E. "Affordable to the Individual Spaceflight".

{{cite web}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The Incredible Ions of Space Propulsion". Science at NASA. NASA. 16 June 2000. Archived from the original on 2011-10-23.

- ^ Sovey, J.S.; Rawlin, V.K.; Patterson, M.J. (May–June 2001). "Ion Propulsion Development Projects in U.S.: Space Electric Rocket Test 1 to Deep Space 1". Journal of Propulsion and Power. 17 (3): 517–526. doi:10.2514/2.5806. hdl:2060/20010093217.

- ^ Penzo, P. (July 1984). Tethers for Mars Space Operations. Vol. 62 Science and Technology Series. pp. 445–465.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Penzo, P; Carroll, J (December 1997). Mars Moons Tether Transport System (PDF) (3rd ed.). pp. 70–71. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2003-03-22.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Illustration of a rotating 'Earth launch assist bolo' capturing a payload and releasing it in a higher orbit. [1]

- ^ "Tether Launch Assist". Tethers Unlimited Inc. Archived from the original on 2003-02-07.

- ^ Newton, K; Canfield, S (6 July 2005). "NASA Engineers, Tennessee College Students Successfully Demonstrate Catch Mechanism for Future Space Tether". News Release. Marshall Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 2005-09-08.

- ^ a b Moravec, H.P. (18–20 October 1977). A Non-Synchronous Orbital Skyhook. 23rd AIAA Meeting - The Industrialization of Space. San Francisco, CA. Archived from the original on 1999-10-09.

- ^ Moravec, H (1978). "Non-Synchronous Orbital Skyhooks for the Moon and Mars with Conventional Materials". Archived from the original on 1999-02-03.

- ^ Moravec, H (1978). "Free Space Skyhooks". Pittsburgh Pa: The Robotics Institute Carnegie-Mellon University. Archived from the original on 1999-10-09.

- ^ Moravec, H (1986). "Orbital Bridges". Pittsburgh Pa: The Robotics Institute Carnegie-Mellon University. Archived from the original on 1999-10-12.

- ^ "Space Tether Bibliography". Tethers Unlimited Inc. Archived from the original on 2014-07-13. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ Baumann, E.; Pado, L.E. (1999). "An Interplanetary Mass Transit System Based on Hypersonic Skyhooks and Magsail-Driven Cyclers" (PDF). Gateway Space Transport Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-08-17.

- ^ Levin, E.M. (2007). "Dynamic Analysis of Space Tether Missions". Advances in the Astronautical Sciences. 126. American Astronautical Society. ISBN 9780877035381.

- ^ "VTOHL Rocketplane". Affordable to the Individual Spaceflight.

{{cite web}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The Next Generation Launch Vehicle". Affordable to the Individual Spaceflight.

{{cite web}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Olds, J.R. (3 September 2009). "A Review of Sample Advanced Space Transportation Concepts". NASA Langley Advanced Space Transportation Workshop. Archived from the original on 2014-07-13.

- ^ Meyer, C. (2008). "Sky Ramp Technology". Archived from the original on 2008-05-17.

- ^ Vertical Accelerator Launch Tower [2]

- ^ Rogers, L. (21 March 2008). It's ONLY Rocket Science. Springer Science and Business Media. p. 298. ISBN 9780387753775.

- ^ Stuhlinger, E., "Possibilities of Electric Space Ship Propulsion", 5th International Astronautical Congress, Innsbruck, Austria, August 5-7, 1954, pp 100-119

- ^ Stuhlinger, E., "Electrical Propulsion System for Space Ships with Nuclear Power", NASA TMX-57089, July 1, 1955

- ^ Stuhlinger, E., and King, J., "Concept for a Manned Mars Expedition with Electrically Propelled Vehicles", Progress in Astronautics Vol. 9, 1963, pp 647-664

- ^ Stevens, N., "Ernst Stuhlinger's Sun Ship", International Space Art Network, video [3]

- ^ Stevens, N., "Ernst Stuhlinger's Umbrella Ship", International Space Art Network, video [4]

- ^ Keaton, P., "A Moon Base/Mars Base Transportation Depot", Lunar Bases and Space Activities of the 21st Century, National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC, Oct 29-31, 1984 [5]

External links[edit]

- Moravec, Hans (1976). "Skyhook proposal".

- Moravec, Hans (1981). "Skyhook proposal".

- Obiwan1976 (2014). "Have you ever dreamed of flying in space?".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Farstrider100 (2014). "What is a Skyhook and why build one?".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Category:Megastructures

Category:Space elevator

Category:Spacecraft propulsion

Category:Vertical transport devices