User:Nøkkenbuer/sandbox

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

"Duck and cover" is a method of personal protection against the effects of a nuclear explosion. Ducking and covering is useful in conferring a degree of protection to practitioners situated outside the radius of the nuclear fireball but still within sufficient range of the nuclear explosion that standing upright is likely to cause serious injury or death. As a countermeasure to the lethal effects of nuclear explosions, it is most effective in the both the event of a surprise nuclear attack, and during a nuclear attack of which the public has received sufficient warning, which is typically between a few seconds to minutes before the nuclear weapon strikes. This countermeasure is intended to replace emergency evacuation when the latter would no longer be viable. Similar procedures are also used during the event of a sudden earthquake or tornado when emergency evacuation is not an option. In the cases of earthquakes and tornadoes, ducking and covering can prevent injury or death which may otherwise occur if no other safety measures are taken.

Procedure[edit]

During a surprise nuclear attack[edit]

| “ | Dropping immediately and covering exposed skin provide protection against blast and thermal effects ... Immediately drop facedown. A log, a large rock, or any depression in the earth's surface provides some protection. Close eyes. Protect exposed skin from heat by putting hands and arms under or near the body and keeping the helmet on. Remain facedown until the blast wave passes and debris stops falling. Stay calm, check for injury, check weapons and equipment damage, and prepare to continue the mission. | ” |

| — US Army field manual FM 3–4 Chapter 4.[1] | ||

Immediately after one sees the first flash of intense light of the developing nuclear fireball, one should stop, get on the ground and under some cover. Then, one should assume a prone-like position, lying face-down and covering exposed skin and the back of one's head with one's clothes; or, if no excess clothes (e.g., coats or scarfs) or coverings (e.g., blankets or quilts) are available, one should cover the back of their head and neck with their hands. Similar instructions, as presented in the Duck and Cover film, are contained in the British 1964 public information film Civil Defence Information Bulletin No. 5.[2] and in the 1980s Protect and Survive public information series.[3]

In US Army training, soldiers are taught to fall down immediately and cover their face and hands in much the same way as is described above.[1]

When warning is given[edit]

Under the conditions where some warning is given, one is advised to find the nearest bomb shelter, or if one could not be found, any well-built building to stay and shelter in place. Sheltering is, as depicted in the film, also the final phase of the "duck and cover" countermeasure in the surprise attack scenario.

Analysis[edit]

The "duck and cover" countermeasure could save thousands. This is because people, being naturally inquisitive, would instead run to windows to try to locate the source of the immensely bright flash generated at the instant of the explosion. During this time, unbeknownst to them, the slower moving blast wave would be rapidly advancing toward their position, only to arrive and cause the window glass to implode, shredding onlookers.[4][5] In the Testimony of Dr. Hiroshi Sawachika, although he was sufficiently far away from the Hiroshima bomb himself and was not behind a pane of window glass when the blast wave arrived, those in his company who were had serious blast injury wounds, with broken glass and pieces of wood stuck into them.[6]

During earthquakes and tornadoes[edit]

Similar advice to "duck and cover" is given in many situations where structural destabilization or flying debris may be expected, such as during an earthquake or tornado. At a sufficient distance from a nuclear explosion, the blast wave produces similar results to these natural phenomenon, so similar countermeasures are taken. In areas where earthquakes are common, a countermeasure known as "Drop, Cover, and Hold On!" is practiced.[7][8][9] Likewise, in tornado-prone areas of the United States, especially those within Tornado Alley, tornado drills involve teaching children to move closer to the floor and to cover the backs of their heads to prevent injury from flying debris.[10][11] Some US States also practice annual emergency tornado drills.[12][13]

Background[edit]

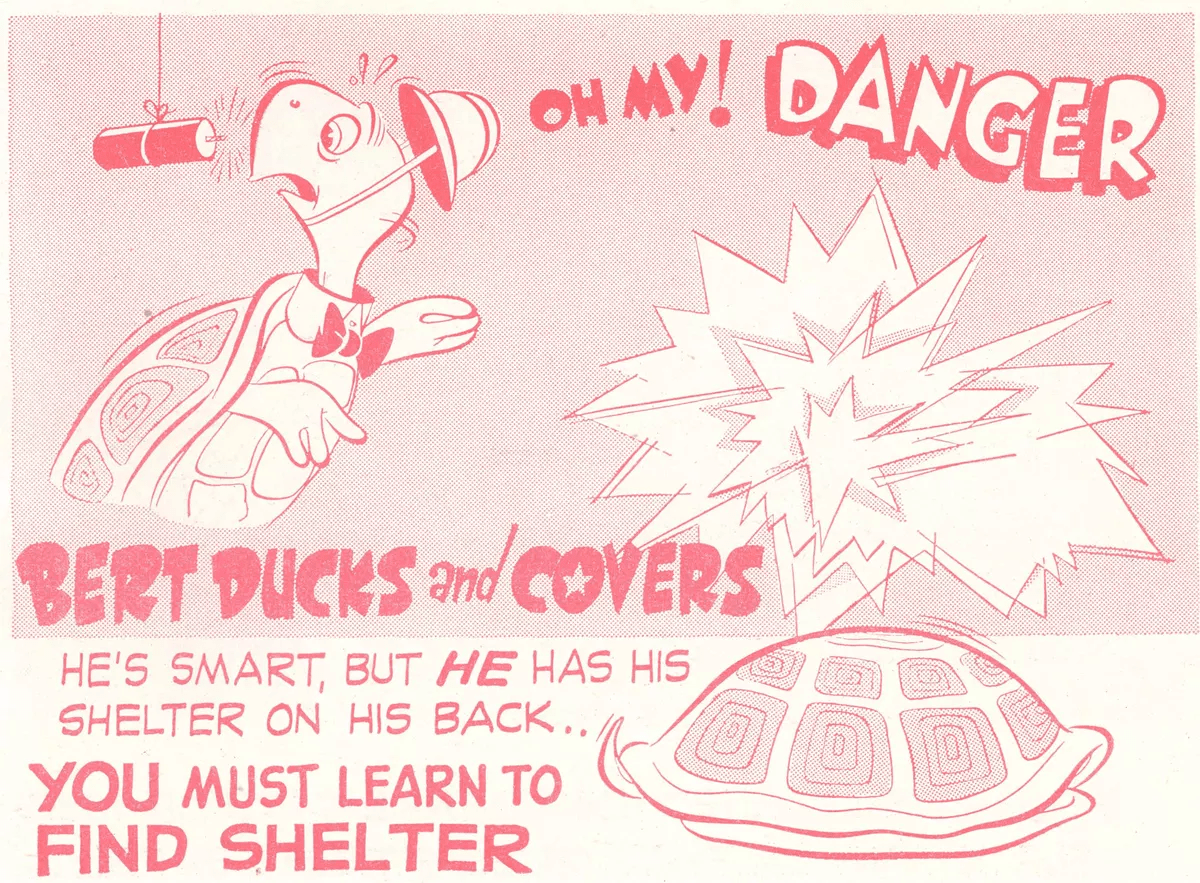

The United States' monopoly on nuclear weapons was broken by the Soviet Union in 1949 when it tested its first nuclear explosive, the RDS-1. With this, many in the US Government, as well as many citizens, perceived that the United States was more vulnerable than it had ever been before. Duck and cover exercises quickly became a part of Civil Defense drills that every US citizen, from children to the elderly, was encouraged to practice so that they could be ready in the event of nuclear war. In 1950, during the first big Civil Defense push of the Cold War—and coinciding with the Alert America! initiative to educate Americans on nuclear preparedness[14]—the film Duck and Cover was produced by the Federal Civil Defense Administration for school showings in 1951.

Detailed assessment[edit]

Within a considerable radius from the surface of the nuclear fireball, 0–3 kilometers—largely depending on the explosion's height, yield and position of personnel—ducking and covering would offer negligible protection against the intense heat, blast and prompt ionizing radiation following a nuclear explosion. Beyond that range, however, many lives would be saved by following the simple advice,[18] especially since at that range the main hazard is not from ionizing radiation but from blast injuries and sustaining thermal flash burns to unprotected skin.[17][19][20][21] Furthermore, following the bright flash of light of the nuclear fireball, the explosion's blast wave would take from first light, 7 to 10 seconds to reach a person standing 3 km from the surface of the nuclear fireball, with the exact time of arrival being dependent on the speed of sound in air in their area.[22][23][24] The time delay between the moment of an explosions flash and the arrival of the slower moving blast wave is analogous to the commonly experienced time delay between the observation of a flash of lightning and the arrival of thunder during a lightning storm, thus at the distances that the advice would be most effective, there would be more than ample amounts of time to take the prompt countermeasure of 'duck and cover' against the blast's direct effects and flying debris.[25] For very large explosions it can take 30 seconds or more, after the silent moment of flash, for a potentially dangerous blast wave over-pressure to arrive at, or hit, your position.[26]

The graphs of lethal ranges as a function of yield, that are commonly encountered,[17][19] are the unobstructed "open air", or "free air" ranges that assume amongst other things, a perfectly level target area, no passive shielding such as attenuating effects from urban terrain masking, e.g. skyscraper shadowing, and so on. Therefore they are thus considered to present an overestimate of the lethal ranges that would be encountered in an urban setting in the real world.[27] With this being most evident following a ground burst with explosive yield similar to first generation nuclear weapons.[27][28]

To highlight the effect that being indoors, and especially below ground can make, despite the lethal open air radiation, blast and thermal zone extending well past her position at Hiroshima,[19] Akiko Takakura survived the effects of the 16 kt atomic bomb at a distance of 300 meters from ground zero, sustaining only minor injuries, due in greatest part to her position in the lobby of the Bank of Japan, a reinforced concrete building, at the time of the nuclear explosion,[29][30] and to highlight the protection conferred to an individual who is below ground during a nuclear air burst, Eizo Nomura survived the same blast at Hiroshima at a distance of 170 meters from ground zero.[31] Nomura, who was in the basement of what is now known as the rest house, also a reinforced concrete building,[31] lived into his early 80s.[32][33][34]

In contrast to these cases of survival, the unknown person sitting outside on the steps of the Sumitomo Bank next door to the Bank of Japan on the morning of the bombing—and therefore fully exposed—suffered what would have eventually been lethal third-degree burns from the near instant nuclear weapon flash if they hadn't then promptly been killed by the slower moving blast wave, when it reached them, ~1 second later.[35]

Blast[edit]

To elucidate the effects on lying flat on the ground in attenuating a weapons blast, Miyoko Matsubara, one of the Hiroshima maidens, when recounting the bombing in an interview in 1999, said that she was outdoors and less than 1 mile from the hypocenter of the Little Boy bomb. Upon observing the nuclear weapons silent flash she quickly lay flat on the ground, while those who were standing directly next to her, and her other fellow students, had simply disappeared from her sight when the blast wave arrived and blew them away.[36][37]

Position of the body can have a considerable influence in protection from blast effects. Lying prone on the ground will often materially lessen direct blast effects because of the protective defilade effects of irregularities in the ground surface. Ground also tends to deflect some of the blast forces upward. Standing close to a wall, even on the side from which the blast is coming, also lessens some of the effect. Orientation of the body also affects severity of the effect of blast. Anterior exposure of the body may result in lung injury, lateral position may result in more damage to one ear than the other, while minimal effects are to be anticipated with the posterior surface of the body (feet) toward the source of the blast.[38]

The human body is more resistant to sheer overpressure than most buildings, however, the powerful winds produced by this overpressure, as in a hurricane, are capable of throwing human bodies into objects or throwing debris at high velocity, both with lethal results, rendering casualties highly dependent on surroundings.[18][39] For example, Sumiteru Taniguchi recounts that, while clinging to the tremoring road surface after the fat man detonation, he witnessing another child being blown away, the destruction of buildings around him and stones flying through the air.[40] Similarly, Akihiro Takahashi and his classmates were blown by the blast of Little Boy by a distance of about 10 meters, having survived due to not colliding with any walls etc. during his flight through the air,[41] Likewise, Katsuichi Hosoya has a near identical testimony.[42]

In the Testimony of Dr. Hiroshi Sawachika, although he was sufficiently far away from the Hiroshima bomb himself and not behind a pane of window glass when the blast wave arrived, those in his company who were had serious blast injury wounds, with broken glass and pieces of wood stuck into them.[43]

According to the 1946 book Hiroshima and other books which cover both bombings,[44] in the days between the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, some survivors of the first bombing went to Nagasaki and told others what they had done to survive after the initial flash and informed them about the particularly dangerous threat of imploding window glass. As a result of this timely warning, a number of lives were saved in the initial blast at Nagasaki. However these informed people were the exception and in both Hiroshima and Nagasaki many died while searching the skies, curious to locate the source of the brilliant flash.[45]

When people are indoors, running to windows to investigate the source of bright flashes in the sky still remains a common and natural response to experiencing a bright flash. Thus, although the advice to duck and cover is over half a century old, ballistic glass lacerations caused the majority of the 1000 human injuries following the Chelyabinsk meteor air burst of February 15, 2013.[46]

The dangers of viewing explosions behind window glass was known of before the Atomic Age began, being a common source of injury and death from large chemical explosions. In the accidental Halifax Explosion of 1917, an ammunition ship exploding with the force of roughly 2.9 kilotons of TNT,[47] and injured the eyes and faces of hundreds of people who looked out of their windows after seeing a bright flash. Every window in the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, was shattered.[48]

During the 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor explosion, a fourth-grade teacher in Chelyabinsk, Yulia Karbysheva, saved 44 children from potentially life-threatening ballistic window glass cuts by ordering them to hide under their desks when she saw the flash. Despite not knowing the origin of the intense flash of light, she ordered her students to execute a duck and cover drill. Ms. Karbysheva, who herself did not duck and cover but remained standing, was seriously lacerated when the explosion's blast wave arrived, and window glass blew in, severing a tendon in one of her arms; however, not one of her students, who she ordered to hide under their desks, suffered a cut.[49] A follow up study of the effects of the meteor airburst determined that the windows most prone to breaking when exposed to a blast overpressure are those of school buildings, which tend to be large in area.[50]

While the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki demonstrated that the urban area of glass breakage is nearly 16 times greater than the area of significant structural/building damage, although improved building codes since then may contribute to better building survival, there would be a higher likelihood of glass breakage and therefore potential injury/death for people near windows because many modern buildings have larger windows.[51]

Flash & burn injuries[edit]

The advice to cover one's exposed skin with anything that can cast a shadow, like the picnic blanket and newspaper used by the family in the film, may seem absurd at first when one considers the capabilities of a nuclear weapon, but even the thinnest of barriers such as cloth or plant leaves would reduce the severity of burns on the skin from the thermal radiation( the thermal radiation/flash is light, similar in average emission spectrum/color to sun light,[58] emitting in the ultraviolet, visible light, and infrared range but with a higher light intensity than sunlight, with this combination of light rays capable of delivering radiant burning energy to exposed skin areas.[59] While the duration of emittance of this burning thermal radiation, which can be experienced by people within range, increases with yield, it is usually at least a few seconds long.[60]) A photograph taken about 1.3 km from the hypocenter of the Hiroshima bomb explosion showed that the shadowing effect of leaves from a nearby shrub protected a wooden utilities pole from charring discoloration due to thermal radiation, while the rest of the telephone pole, not under the protection of the leaves, was charred almost completely black.[61]

Prompt nuclear radiation[edit]

Ducking and covering would also slightly reduce exposure to the initial gamma rays, particularly the portion emitted after the flash.[62] These initial gamma rays are emitted from the fireball & following mushroom cloud and can reach personnel on the ground for a total of approximately 1 minute.[63] Since gamma rays are mostly emitted in a straight line, people laying on the ground will have a higher chance to have obstacles serving as radiation protection such as building walls, foundations, car engines, etc. between their bodies and the radiation emitted from the initial fireball and the accompanying lower level of radiation still being emitted through to the beginning of the mushroom cloud phase, known as "cloudshine",[64] or that down scattered by the air/"skyshine".[65]

Delayed nuclear radiation, "fallout"[edit]

If the nuclear detonation is exploded as a surface bursts, after its "prompt effects" of initial flash, blast and initial radiation have ended, another immediately life threatening danger may begin to form. The low "height of burst" of the surface burst results in conditions were the fireball touches the ground and therefore lifts soil up into the cloud where the radioactive isotope products of the nuclear reactions that produced the explosion, coalesce with the heavy soil. This mixture, once cooled, begins to locally fall-out or precipitate out of the mushroom cloud, falling back to the surface of the earth, near to the point of detonation, over the next few minutes and hours.[66]

While the Duck and cover countermeasure, in its most basic form, offers a small to negligible protection against fallout; the technique assumes that after the effects of the blast and initial radiation subside, with the latter of which being no longer a threat after about "twenty seconds" to 1 minute post detonation,[63][67] a person who ducks and covers will realize when it is wise to cease ducking and covering (after the blast and initial radiation danger has passed) and to then seek out a more sheltered area, like an established or improvized fallout shelter to protect themselves from the ensuing potential local fallout danger, as depicted in the film. However if such a shelter is unavailable, the person should then be advised to follow the Shelter in Place protocol, or if given, Emergency evacuation advice. Evacuation orders would entail exiting the area completely by following a path perpendicular to the wind direction, and therefore perpendicular to the path of the fallout plume.[68] While "sheltering in place" is staying indoors, in a preferably sealed tight basement, or internal room, for a number of hours, with the oxygen supply available in such a scenario being more than sufficient for 3+ hours in even the smallest average room, under the assumption that the improvised seal is perfect, until carbon dioxide levels begin to reach unsafe values and necessitate room unsealing for a number of minutes to create a room air change.[69][70]

After all, "Duck and Cover" is a first response countermeasure only, in much the same way that "Drop, Cover and Hold On" is during an earthquake, with the advice having served its purpose once the earthquake has passed, and possibly other dangers—like a tsunami—may be looming.

In the era the advice was originally given, the most common nuclear weapons were weapons comparable to the US Fat Man and Soviet Joe-1 in yield. The most far-reaching dangers that initially come from the nuclear explosion of this, and higher, yield weapons as airbursts, are the initial flash/heat and blast effects and not from fallout. This is due to the fact that when nuclear weapons are detonated to maximize the range of building destruction, that is, maximize the range of surface blast damage, an airburst is the preferred nuclear fuzing height, as it exploits the mach stem phenomenon. This phenomenon of a blast wave occurs when the blast reaches the ground and is reflected. Below a certain reflection angle the reflected wave and the incident wave merge and form a reinforced horizontal wave, this is known as the 'Mach stem' (named after Ernst Mach) and is a form of constructive interference and consequently extends the range of high pressure.[71][72][73][74] Air-burst fuzing, as one would expect, increases the range that peoples skin will have a line-of-sight with the nuclear fireball. However, as a result of the high altitude of the explosion, most of the radioactive bomb debris/ is dispersed into the stratosphere, with a great column of air therefore placed between the vast majority of the bomb debris/fission reaction products and people on the ground for a number of crucial days before it falls out of the atmosphere in a comparatively dilute fashion, this "delayed fallout" is henceforth not an immediate concern to those near the blast. On the other hand, the only time that fallout is rapidly concentrated in a potentially lethal fashion in the local/regional area around the explosion is when the nuclear fireball makes contact with the ground surface, with an explosion that does so, being aptly termed a surface burst.[75] For example in the Operation Crossroads tests of 1946 on Bikini Atoll, using two explosive devices of the same design and yield, the first, Test Able (an air burst) had little local fallout, but the infamous Test Baker a near surface shallow (underwater burst) left the local test targets badly contaminated with radioactive fallout.

Widespread radioactive fallout itself was not recognized as a threat among the public at large before 1954, until the widely publicized story of the 15-megaton surface burst of the experimental test shot Castle Bravo on the Marshall Islands. The explosive yield of the Castle Bravo device the Shrimp was unexpectedly high, and therefore correspondingly higher amounts of local fallout were produced. When this arrived at their location carried by the wind, this caused the 23 crew members on a Japanese fishing boat known as the Lucky Dragon to come down with acute radiation sickness with varying degrees of seriousness and due to complications in the treatment of the ship's radio operator months after the exposure, resulted in his death.

A notable comparison to underline this is found when one compares the 50 megaton air-burst Tsar Bomba, which produced no concentrated local/early fallout, and thus no known deaths from radiation, with the surface burst of the 15 megaton Castle Bravo, which in comparison, due to the local fallout produced, was implicated in the death of 1 of 23 crew on the Lucky Dragon and made the entire Bikini Atoll unfit for further nuclear testing until enough time elapsed and the intensity of the radiation field had decayed to acceptable levels.[note 1]

Furthermore, regardless of if a nuclear attack on a city is of the surface or air-burst variety or a mixture of both, the advice to shelter in place, in the interior of well-built homes, or if available, fallout shelters, as suggested in the film Duck and Cover, will drastically reduce ones chance of absorbing a hazardous dose of radiation.[79] A real world example of this occurred after the Castle Bravo test where, in contrast to the crew of the Lucky Dragon, the firing crew that triggered the explosion safely sheltered in their firing station until after a number of hours had passed and the radiation levels outside fell to dose rate levels safe enough for an evacuation to be considered.[80][81] The comparative safety experienced by the Castle Bravo firing crew served as a proof of concept to civil defense personnel that Shelter in place (or "buttoning up" as it was known then) is an effective strategy in mitigating the potentially serious health effects of local fallout.[80]

The minimum typical protection factor of the fallout shelters in US cities is 40 or more, in many cases these shelters are nothing more than the interior of pre-existing well-built buildings that have been inspected, and following their protection factors being calculated, re-purposed as fallout shelters.[82][83][84][85]

A protection factor of at least 40 means that the Radiation shielding provided by the shelter reduces the radiation dose experienced by at least 40 times that which would be experienced outside the shelter with no shielding. "Protection factor" is equivalent to the modern term "dose reduction factor".[25]

During the first hour after a nuclear explosion, radioactivity levels drop precipitously. Radioactivity levels are further reduced by about 90% after another 7 hours and by about 99% after 2 days.[68] An accurate rule of thumb for approximating the radioactive dose rate produced by the decay of the myriad of isotopes present in nuclear fallout is the "7/10 rule".[88] The rule states that for each 7 fold increase in time the dose rate drops by a factor of 10.[89] For example, assuming the fallout process has ended and the dose rate is a lethal in one hour exposure, 500 roentgens per hour, at one hour after detonation, then 7 hours after detonation the rate will be 50 R/hr, 49 hours after detonation (7×7 hours) the dose rate will be 5 R/hr, 343 hours after detonation (49×7—or about 2 weeks) the dose rate will be about 0.5 R/hr, at which point no special precautions would need to be taken and venturing outside into that dose rate for an hour or two would pose a close to negligible health hazard,[90] thus permitting an evacuation to be done with acceptable safety to a known contamination free zone. Following a nuclear detonation approximately 80 percent of the fallout would be deposited on the ground during the first 24 hours.[26]

Some agencies that promoted “evacuate immediately” guidance as a response to potentially lethal fallout arriving, advice which may have been influenced by these agencies assuming simplistic single wind driven cigar/Gaussian shaped fallout contours would be representative of reality, have since retracted this advice, as this can actually result in higher radiation exposures as it would put people outdoors and in harm’s way when the radiation levels would be highest. The Modeling and Analysis Coordination Working Group (MACWG)-which was set up to resolve conflicting advice given by various agencies, has reaffirmed that the best blanket advice that would reduce the number of casualties by the greatest amount is: "Early, adequate sheltering followed by informed, delayed evacuation."[51]

Expert advice published in the 2010 document Planning Guidance for Response to a Nuclear Detonation is to shelter in place, in an area away from building fires, for at least 1 to 2 hours following a nuclear detonation and fallout arriving,[91] with the greatest benefit, assuming personnel are in a building with a high protection factor, is sheltering for no less than 12 to 24 hours before evacuation.[25] Therefore, sheltering for the first few hours can save lives.[92] Indeed death and injury from local fallout is regarded by experts as the most preventable of all the effects of a nuclear detonation, being simply dependent on if personnel know how to identify an adequate shelter when they see one and enter one quickly, with the number of potential people saved being cited as in the hundreds of thousands.[93][94][95][96] Or even higher if the remaining occupants of the city are made aware of the contaminated areas, by emergency systems, within hours of the events aftermath.[95][97] In 2009-2013 a further iteration on sheltering in place was made to determine the optimal improvised fallout shelter residence times following a nuclear detonation, with computer analysis, it was found individuals should quickly get into the best intact building at least under 5 minutes distant in travel time following the detonation and they should stay there for at least 30 minutes before venturing out to find a shelter with a higher protection factor but that is a greater travel time away +10 minutes.[98][99][100] However, although this would be effective in cases were the initial building protection factor is less than about 10, it would require a high degree of individual situational awareness that may be optimistic following the shock of a nuclear detonation, in any case, if a building with a PF of 20 or more is nearby, such as the fallout shelters depicted in the film, in the vast majority of fallout circumstances, it would not be advisable to leave it until 3+ hours have elapsed following the initial arrival of the local fallout.[95][96]

Following a single IND(improvized nuclear device) detonation in the US, the National Atmospheric Release Advisory Center(NARAC) would, within minutes to at most hours, after the detonation have a reliable prediction of the fallout plume size and direction, and when armed with this prediction would then begin attempting to corroborate this with readings from radiation survey meter equipment that would fly over close to the ground in the affected area by means of helicopter or drone(UAV) aircraft that would also follow within tens of minutes to at most hours after the detonation,[note 2] Once a general outline and direction of the fallout is determined, the next step is to disseminate this information to citizens sheltering-in-place by loudspeaker, radio, cell phone etc., with a “Fallout App” containing maps for smart phones being regarded as an area of interest so that survivors don't inadvertently evacuate downwind further into harms way.[101][102]

Nuclear electromagnetic pulse, Non-lethal[edit]

In respect to the other non-lethal weapon effects from an detonation on or near the surface, the detonation's blast wave would likely produce a momentary electric grid blackout due to the loss of a large portion of a cities electrical equipment drawing power/electrical load, while the Nuclear electromagnetic pulse(EMP) from a surface/ground-burst explosion would cause little damage outside the blast area, so cell phone towers that survive the blast should be capable of carrying communications.[101] Although if communications during the 9/11 attacks or after a major hurricane are anything to go by, and the cell phone network towers survive, the service would be overloaded(a Mass call event) and thereby made useless soon after; however, if prior arrangements between the cell network and emergency responders are made to give them priority and bar access to all other individuals, then it may be an effective service. However, as Civil defense(CD) shelters, as depicted in the film, were stocked for such an eventuality, they contained amongst other things, at least one CDV-715 radiation survey meter and a CD emergency radio receiver which would respectively be used to facilitate a safe delayed evacuation, regardless of outside help and if communications continued, inform them of the outside situation as it developed.

Historical and psychological assessment[edit]

Some historians have thus far sought to dismiss civil defense advice as mere propaganda, despite, as other historians have found, detailed scientific research programs laying behind the much-mocked government civil defense pamphlets of the 1950s and 1960s, including the prompt advice of ducking and covering.[85]

The exercises of Cold War civil defense are seen by historian Guy Oakes in 1994, as having less practical use than psychological use: to keep the danger of nuclear war high on the public mind, while also attempting to assure the American people that something could be done to defend against nuclear attack.[103] However, according to contemporary Cold War civil defense pamphlets, like Civil Defence why we need it released in 1981, civil defense countermeasures were presented as analogous to seat belts, and that the suggestion that knowing what steps to take in the "slight" possibility that a nuclear explosion occurs in your region, keeps such calamities high on the public mind, is "like saying people who wear seat belts are expecting to have more crashes than those who do not", and as with a seat belt, there is never a suggestion that if the countermeasure were implemented, it would save everyone. Moreover civil defense was not solely a US-UK or nuclear club phenomenon, countries with long histories of neutrality, such as Switzerland, are "foremost in their civil defence precautions."[104] The Swiss civil defense network has an overcapacity of nuclear fallout shelters for the country's population size, and by law, new homes must still be built with a fallout shelter as of 2011.[105][106]

Tornadoes[edit]

Ducking and covering does have certain applications in other, more natural disasters. In states prone to tornadoes, if time does not permit seeking better shelter—such as a storm cellar—during a tornado warning, school children are taught to perform a countermeasure similar to "duck and cover" by sitting up against a solid inner wall of a school. The countermeasure is widely practiced in schools along the West Coast of the United States.[citation needed]

Earthquakes[edit]

In an earthquake, (which are generally of a natural tectonic plate origin although they can be artificially generated by the detonation of a nuclear explosive device in which sufficient energy is transmitted into the ground, with an extreme case to serve as an example of this phenomenon being the Operation Grommet Cannikin test of the 5 megaton W71 warhead exploded deep underground on Amchitka Island in 1971, which produced a seismic shock quake of 7.0 on the Richter scale) people are encouraged, regardless of the cause of the quake, to ";drop, cover, and hold on": to get underneath a piece of furniture, cover their heads and hold on to the furniture. This advice also encourages people not to run out of a shaking building, because a large majority of earthquake injuries are due to broken bones from people falling and tripping during shaking. While it is unlikely that "drop, cover and hold on" will protect against a building collapse, buildings built in earthquake-prone areas in the United States are usually built to earthquake Life Safety Building codes,[107][108][109][110] and thus a building collapse of these structures (even during an earthquake) is rare. "Drop, cover and hold on" may not be appropriate for all locations or building types, but the red cross advises,[111] it is the appropriate emergency response to an earthquake in the United States.

Notes:

- ^ By 1958, a total of 23 nuclear devices were exploded on or near the atoll,[1] with the majority occurring after the 1954 Operation Castle series, resulting in a total of about 42 megatons of pure fission product fallout being generated around the atoll, this made permanent above ground habitation without remediation unwise for a decade or so, it was thus resettled in 1968. The inhabitants lived there again from 1968 to 1978, abandoning the atoll in 1978. As of 2014, the Atoll has had infrequent inhabitants since the 1990's, mainly for tours, a return to permanent safe habitation would require locally produced and consumed plant food to be grown with fertilizer, or alternatively, only imported plant food to be eaten.[2][3]

- ^ As this ground hugging fly over has the potential to be mistaken for airlift rescue attempts, which are common after other natural disasters, survivors should not exit shelter unless absolutely necessary in the time period before being informed of the fallout situation, or alternatively, stay in shelter until sufficient time has elapsed, +24 hrs for a delayed evacuation to take place.

[edit]

- Stop, drop and roll - Advice for when one is on fire and no other means of extinguishing the flames are available.

- Abo Elementary School - Underground school built in the 1960s, used until the 1990s

- National Response Scenario Number One

- Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center

- Mass-casualty incident

- Duck and Cover (film)

- A Day Called X a dramatized 1957 CBS documentary following the evacuation drill of the entire city of Portland Oregon per Civil Defense protocol, in response to the RADAR detection of an en-route Soviet nuclear bomber force.

- Nuclear War Survival Skills

- Protect and Survive

- The House in the Middle

- The Atomic Café

- Storm cellar

- Air raid shelter

- Bomb shelter

- Blast shelter

- Fallout shelter

- Civil Defense Geiger counters

- Civil Defence Information Bulletin

- CONELRAD

- Nuclear Emergency Support Team

- Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission - upon whose work the writers of Duck and Cover heavily borrowed.

- Desert Rock exercises

- Operation Teapot

- Project 4.1

- Project SUNSHINE

- Comparison of Chernobyl and other radioactivity releases

- Radiobiology

- Radioecology

- The Geochemist's Workbench

- Nuclear Winter

- Semipalatinsk Test Site

- Nevada Test Site

- Pacific Proving Grounds

- Enewetak atoll

- Pechora–Kama Canal

- Amchitka

- Novaya Zemlya

- List of nuclear weapons#Soviet Union.2FRussia

- Subsidence crater

- High-altitude nuclear explosion

- List of artificial radiation belts

- Nuclear arms race

- nuclear terrorism

- fuel grade/reactor grade plutonium test

- Nth Country Experiment

See also, long-term survival[edit]

- Hiroshima (book)

- Hibakusha - survivors of prompt radiation with comparatively little to no fallout exposure

- Project 4.1 - health effects of heavy thermonuclear fallout exposure

- Ex-Rad a medicinal product being tested for its effects at increasing human radioresistance

- Nuclear War Survival Skills (book)

- Fallout Protection

- Radioactive decontamination

- Cactus Dome - successful fallout decontamination and sequestering

- Chernobyl exclusion zone

- Wood gas generator - power

- Wood gas vehicle - transport

- Red Forest - heavily contaminated forest, with controlled biomass power burning suggested to prevent a re-suspension of fallout that would occur following a wildfire.

- Anaerobic waste digestion for fuel production

- Bioconversion of biomass to mixed alcohol fuels

- Amateur radio emergency communications - post disaster networking

- Emergency Preparedness

- Preparedness

- Continuity of Government

- HurriQuake

- Hurricane-proof building

- Blast shelter

- anti-flash white paint

- White wash paint

- The House in the Middle Film that demonstrates the effects of white wash on flash protection

- Autonomous building homes

- Earthship homes

- Removal of ions and dissolved substances from Water

- Seed bank

- Enriched CO2 greenhouse air agriculture

- Aeroponics agriculture with low water usage requirements

- BIOS-3

- Self-sustainability

- Remanufacturing

- Repurposing

- intermediate technology

- Primitive skills

- David J. Gingery DIY author of machine tool books

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Nuclear Protection". Nuclear, Biological, Chemical Protection Field Manual (FM 3-4). Washington, DC: US Department of Defense. 21 February 1996. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013.

- ^ "Civil Defence Bulletin – No. 5" (video). YouTube. 25 December 2006. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Protect and Survive: Action After Warnings 28:27–28:50 (part 10)" (video). 10. YouTube. 9 December 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Connor, Shane (24 August 2006). "The good news about nuclear destruction". WND. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

Thousands can be saved employing the old 'Duck and Cover' tactic, without which most people will instead run to the nearest window to see what the big flash was just in time to be shredded by the glass imploding inward from the shock wave.

- ^ Conner, Shane. "The Good News About Nuclear Destruction". KI4U. KI4U, Inc. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

...most can save themselves by immediately employing the 'Duck & Cover' tactic, rather than just allowing an impulsive rush to the nearest windows to see what that 'bright flash' was across town, just-in-time to be shredded by the glass imploding inward from that delayed shock wave blast.

- ^ Sawachika, Hiroshi. "Hiroshima Survivors' Testimony – Testimony of Hiroshi Sawachika, 1986". Hanover College History Department. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ "Great ShakeOut Earthquake Drills - Drop, Cover, and Hold On". ShakeOut. Southern California Earthquake Center. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ "How to Protect Yourself During an Earthquake... Drop, Cover, and Hold On!". Earthquake Country Alliance. Earthquake Country Alliance. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ "Drop, Cover, & Hold". CUSEC. Central United States Earthquake Consortium. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ "Florida Disaster". 2007-02-05. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ "Plano, Texas ISD". Pisd.edu. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ "Tornado Drill". VA Emergency. Virginia Department of Emergency Management. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ "South Carolina Severe Weather Awareness Week". SCEMD. South Carolina Emergency Management Division. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ "ALERT AMERICA!". CONELRAD. CONELRAD.com. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ a b Walker, John (June 2005). "Nuclear Bomb Effects Computer". Fourmilab. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ^ Walker, John (June 2005). "Nuclear Bomb Effects Computer Revised Edition 1962, Based on Data from The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, Revised Edition "The maximum fireball radius presented on the computer is an average between that for air and surface bursts. Thus, the fireball radius for a surface burst is 13 percent larger than that indicated and for an air burst, 13 percent smaller."". Fourmilab. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ^ a b c "Mock up". Remm.nlm.gov. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ a b "The Nuclear Matters Handbook". Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs. 1991. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

Individuals who sense a blinding white flash and intense heat coming from one direction should immediately fall to the ground and cover their heads with their arms. This provides the highest probability that the air blast will pass overhead without moving them laterally and that debris in the blast wave will not cause impact or puncture injuries. Exposed individuals who are very close to the detonation have no chance of survival. At distances at which a wood frame building can survive, however, exposed individuals significantly increase their chance of survival if they are on the ground when the blast wave arrives and if they remain on the ground until after the negative phase blast wave has moved back toward ground zero

- ^ a b c "Range of weapons effects". Johnstonsarchive.net. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ Christy, Robert F. "Little Boy on Hiroshima" (video). Web of Stories. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|content=ignored (help) - ^ Nuclear Warfare Lecture 9 by Professor Grant J. Matthews of University of Notre Dame OpenCourseWare. page 3. negligible. Meaning that if one were close enough to get a harmful dose of radiation from a generic 1 megaton weapon, one would very likely die from blast effects alone at that proximity.

- ^ "The Nuclear Matters Handbook". Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs. 1991. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

"Initially, this blast wave moves at several times the speed of sound, but it quickly slows to a point at which the leading edge of the blast wave is traveling at the speed of sound, and it continues at this speed as it moves farther away from ground zero

- ^ "Nuclear Warfare Lecture 14 by Professor Grant J. Matthews of University of Notre Dame OpenCourseWare. Mechanical Shock velocity equation". Archived from the original on 2013-12-19.

- ^ Analytical proof of the Taylor equation including Taylor’s constant Sγ which previously required numerical integration, with applications, Nigel Cook. PDF

- ^ a b c "Planning Guidance for Response to a Nuclear Detonation" (PDF) (2nd ed.). National Library of Medicine. June 2010. Retrieved 2013-11-30. Cite error: The named reference "Planning Guidance" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "Nuclear Blast". Ready.gov. 2013-04-17. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ a b "Modelling the effects of nuclear weapons in an urban setting" (2011)

- ^ "UCRL-TR-231593. Thermal Radiation from Nuclear. Detonations in Urban. Environments. R. E. Marrs, W. C. Moss, B. Whitlock. June 7, 2007" (PDF).

- ^ "Hiroshima Witness interview". Pcf.city.hiroshima.jp. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ "Testimony of Akiko Takakura | The Voice of Hibakusha | The Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki | Historical Documents". atomicarchive.com. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ a b "Special Exhibit 3". Pcf.city.hiroshima.jp. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ ""Hiroshima – 1945 & 2007" by Lyle (Hiroshi) Saxon, Images Through Glass, Tokyo". D.biglobe.ne.jp. 1945-08-06. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ "Hiroshima: A Visual Record". JapanFocus. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ "Japan". Kombe-jarvis.com. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ "Look at the Exhibits/Damage by the Heat Rays". Pcf.city.hiroshima.jp. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ Matsubara, Miyoko. "Continue to Relate Stupidity of War and Dignity of Life". The Spirit of Hiroshima. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ Matsubara, Miyoko (1999). "The Spirit of Hiroshima". Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. Archived from the original on 2013-04-20. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

I quickly lay flat on the ground. Just at that moment, I heard an indescribable deafening roar. My first thought was that the plane had aimed at me"..."I had no idea how long I had lain unconscious, but when I regained consciousness the bright sunny morning had turned into night. Takiko, who had stood next to me, had simply disappeared from my sight. I could see none of my friends nor any other students. Perhaps they had been blown away by the blast.

- ^ Coates, Jr., James Boyd; Beyer, James C., eds. (1984). "II: Ballistic Characteristics of Wounding Agents". Wound Ballistics in World War II – Supplemented by Experiences in the Korean War. Washington, D.C.: The Historical Unit, United States Army Medical Service. LCCN 62-60002.

- ^ "1) Effects of blast pressure on the human body" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-10-12.

- ^ "Interview with Sumiteru Taniguchi Japanese Citizen, Nagasaki". People's Century: Fallout. PBS. 1999-06-15. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ^ "Hiroshima Survivors' Testimony, Reformatted from the Original Electronic Text at Voice of Hibakusha".

- ^ "'What Happened On This Date' It's hot! Help! Water please! - Hiroshima 8/6 Recreated (August 6, 2005, The Asahi Shimbun Newspaper Morning Edition) Katsuichi Hosoya has a similar account of being "blown several meters"".

- ^ Sawachika, Hiroshi. "Hiroshima Survivors' Testimony – Testimony of Hiroshi Sawachika, 1986". Hanover College History Department. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Nine Who Survived Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Personal Experiences of Nine Men Who Lived through both Atomic Bombings Hardcover – January 1, 1957 by Robert Trumbull, pg 25,28,61,101,109,119

- ^ Nine Who Survived Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Personal Experiences of Nine Men Who Lived through both Atomic Bombings Hardcover – January 1, 1957 by Robert Trumbull, pg 25,28,61,101,109,119

- ^ Heintz, Jim (2013-02-15). "Emergency Situations Ministry spokesman Vladimir Purgin said many of the injured were cut as they flocked to windows to see what caused the intense flash of light, which momentarily was brighter than the sun". Canada.com. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ Ruffman, Alan and Howell, Colin D. (edited by). Ground Zero: A Reassessment of the 1917 Explosion in Halifax Harbour (1994, Nimbus Publishing), p.276.

- ^ McAlister, Chryssa N.; Murray, T. Jock; Lakosha, Hesham; Maxner, Charles E. (June 2007). "The Halifax disaster (1917): eye injuries and their care". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 91 (6): 832–5. doi:10.1136/bjo.2006.113878. PMC 1955605. PMID 17510478.

- ^ "After Assault From the Heavens, Russians Search for Clues and Count Blessings". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ http://cams.seti.org/index-chelyabinsk.html

- ^ a b c d "Reducing the Consequences of a Nuclear Detonation: Recent Research Author: Brooke Buddemeier, 2010 NAE".

- ^ "The Nuclear Matters Handbook: Expanded Edition – Appendix F: The Effects of Nuclear Weapons". Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs. 1991. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

Anything that casts a shadow or reduces light, including buildings, trees, dust from the blast wave, heavy rain, and dense fog, provides some protection against thermal burns or the ignition of objects. Transparent materials, such as glass or plastic, will slightly attenuate thermal radiation"

- ^ Original caption: "Shadow" of band valve wheel on paint of a gas holder at Hiroshima. Radiant heat instantly burned paint where the heat rays were not obstructed. 6,300 feet from ground zero (Japanese photo). United States Strategic Bombing Survey, The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (United States Government Printing Office: Washington, 1946) Chapter 3.

- ^ Kerr, George D.; Young, Robert W.; Cullings, Harry M.; Christy, Robert F. (2005). "Bomb Parameters". In Robert W. Young, George D. Kerr (ed.). Reassessment of the Atomic Bomb Radiation Dosimetry for Hiroshima and Nagasaki – Dosimetry System 2002 (PDF). The Radiation Effects Research Foundation. pp. 42–43.

- ^ Malik, John (September 1985). "The Yields of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Explosions" (PDF). Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ Malik (1985) describes how various values were recorded for the B-29's altitude at the moment of bomb release over Hiroshima. The strike report said 30,200 ft, the official history said 31,600 ft, Commander Parson's log entry was 32,700 ft, and the navigator's log was 31,060 ft—the latter possibly an error transposing two digits. A later calculation using the indicated atmospheric pressure arrived at the figure of 32,200 ft.

Similarly, several values have been reported as the altitude of the Little Boy bomb at the moment of detonation. Published sources vary in the range of 1,800 to 2,000 ft (550 to 610 m) above the city. The device was set to explode at 1,885 ft (575 m), but this was approximate. Malik (1985) uses the figure of 1,903 ft (580 m) plus or minus 50 ft (15 m), determined after data review by Hubbell et al. (1969). Radar returns from the tops of multistory buildings near the hypocenter may have triggered the detonation at a somewhat higher altitude than planned. Kerr et al. (2005) found that a detonation altitude of 600 m (1,968.5 ft), plus or minus 20 m (65.6 ft), gave the best fit for all the measurement discrepancies. - ^ "Planning Guidance for Response to a Nuclear Detonation (figure 1.5)" (PDF). Remm.nlm.gov. Retrieved 2013-11-30.r

- ^ http://dge.stanford.edu/SCOPE/SCOPE_28_1/SCOPE_28-1_1.1_Chapter1_1-23.pdf SCOPE report, page 6

- ^ "Thermal Radiation and Its Effects : Chapter VII" (PDF). Fourmilab.ch. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ Field Manual No.1-111: Aviation Brigades - Google Boeken. ISBN 9781428911024. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ "Damage by the Heat Rays/Shadow Imprinted on an Electric Pole". Pcf.city.hiroshima.jp. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ "The advantage of lying prone in reducing the dose of gamma rays from an airburst atomic... | The National Archives". Discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ a b "The Nuclear Matters Handbook".

For surface and low-air bursts, the fireball will rise quickly, and within approximately one minute, it will be at an altitude high enough that none of the gamma radiation produced inside the fireball will have any impact to people or equipment on the ground. For this reason, initial nuclear radiation is defined as the nuclear radiation produced within one minute post-detonation. Initial nuclear radiation is also called prompt nuclear radiation.

- ^ http://www.remm.nlm.gov/nuclearexplosion.htm

- ^ Structure shielding against fallout gamma rays from nuclear detonations By Lewis Van Clief Spencer, Arthur B. Chilton, Charles Eisenhauer, Center for Radiation Research, United States. National Bureau of Standards, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. pg 562-568

- ^ The Unexpected Return of 'Duck and Cover', Glenn Harlan Reynolds Jan 4 2011

- ^ Structure shielding against fallout gamma rays from nuclear detonations By Lewis Van Clief Spencer, Arthur B. Chilton, Charles Eisenhauer, Center for Radiation Research, United States. National Bureau of Standards, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. pg 56

- ^ a b "Nuclear Attack" (PDF). Dhs.gov. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ "Journal of Hazardous Materials A119 (2005) 31–40 Effectiveness of expedient sheltering in place in a residence , James J. Jetter, Calvin Whitfield" (PDF).

- ^ Bennett, James S. (2009). "A systems approach to the design of safe-rooms for shelter-in-place". Building Simulation. 2: 41–51. doi:10.1007/S12273-009-9301-2. S2CID 109770220. (subscription required)

- ^ "The Mach Stem | Effects of Nuclear Weapons". atomicarchive.com. Retrieved 2014-04-26.

- ^ "Nuclear Weapon Blast Effects". Fas.org. Retrieved 2014-04-26.

- ^ [4] video of the mach 'Y' stem, note that it is not a phenomenon unique to nuclear explosions, conventional explosions also produce it.

- ^ "MACH STEM MODELING WITH SPHERICAL SHOCK WAVES , AFIT/GNE/ENP/85M-6 by William E. Eichinger , 1985" (PDF).

- ^ "The Effects of Nuclear Weapons". Fourmilab.ch. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ "Planning Guidance for Response to a Nuclear Detonation (figure 3.1)" (PDF). Remm.nlm.gov. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ Structure shielding against fallout gamma rays from nuclear detonations By Lewis Van Clief Spencer, Arthur B. Chilton, Charles Eisenhauer, Center for Radiation Research, United States. National Bureau of Standards, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. pg 41

- ^ "Annual report of the office of civil defense 1968. National Fallout Shelter Survey pg 29,37-38" (PDF).

- ^ "Radiological and Nuclear Incidents". Travel.state.gov. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ a b Dr. John C. Clark as told to Robert Cahn (July 1957). "Trapped by Radioactive Fallout, Saturday Evening Post" (PDF). accessed Feb 20, 2013

- ^ "Operation Castle Bravo Blast". Dgely.com. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ "Radioactive Fallout and Shelter : U S Office Of Civil Defense : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ Structure shielding against fallout gamma rays from nuclear detonations By Lewis Van Clief Spencer, Arthur B. Chilton, Charles Eisenhauer, Center for Radiation Research, United States. National Bureau of Standards, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. pg 27,29,37,41 & ref 48

- ^ "Standards for fallout shelters FEMA TR-87, 1979".

- ^ a b "Architects of Armageddon: the Home Office Scientific Advisers' Branch and civil defence in Britain, 1945–68". Journals.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ "Planning Guidance for Response to a Nuclear Detonation (figure 1.8)" (PDF). Remm.nlm.gov. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ Structure shielding against fallout gamma rays from nuclear detonations By Lewis Van Clief Spencer, Arthur B. Chilton, Charles Eisenhauer, Center for Radiation Research, United States. National Bureau of Standards, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. pg 137 to 148

- ^ The Unexpected Return of 'Duck and Cover', Glenn Harlan Reynolds Jan 4 2011

- ^ "Radiation Effects of a Nuclear Bomb" (PDF). 3.nd.edu. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ "Understanding Radioactive Fallout". Nikealaska.org. 2006-01-07. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ "Nuclear Detonation: Weapons, Improvised Nuclear Devices - Radiation Emergency Medical Management". Remm.nlm.gov. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ "Nuclear Detonation: Weapons, Improvised Nuclear Devices - Radiation Emergency Medical Management". Remm.nlm.gov. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ "Reducing consequences of nuclear detonation". YouTube. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ "Brooke Buddemeier, Nuclear Detonation in a Major City". YouTube. 2011-06-21. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ a b c "Analysis of Sheltering and Evacuation Strategies for a National Capital Region Nuclear Detonation Scenario, SANDIA REPORT, SAND 2011-9092 Unlimited Release Published December 2011. Authors: Larry D. Brandt, Ann S. Yoshimura" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Analysis of Sheltering and Evacuation Strategies for an Urban Nuclear Detonation Scenario (Los Angeles) SANDIA REPORT SAND2009-3299 Unlimited Release Printed May 2009, Authors: Larry D. Brandt, Ann S. Yoshimura" (PDF).

- ^ "Social Computing, Behavioral-Cultural Modeling and Prediction Lecture Notes in Computer Science Volume 7812, 2013, pp 476-485 Modeling the Interaction between Emergency Communications and Behavior in the Aftermath of a Disaster". doi:10.1007/978-3-642-37210-0_52.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ http://www.gizmag.com/survive-nuclear-bomb-shelter/31057/

- ^ http://www.dev-john.thejournal.ie/what-to-do-when-theres-an-atomic-bomb-1265502-Jan2014/

- ^ http://rspa.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/470/2163/20130693

- ^ a b "A Nuclear Explosion in a City or an Attack on a Nuclear Reactor Author: Richard L. Garwin, 2010".

- ^ "Nuclear Detonation: Weapons, Improvised Nuclear Devices, Communicating After an IND Detonation: Resource for Responders and Officials".

- ^ Oakes, Guy. The Imaginary War: Civil Defense and Cold War Culture. 1994, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509027-6, pp. 66–68

- ^ "CIVIL DEFENCE why we need it".

- ^ Ball, Deborah (2011-06-25). "Swiss Renew Push for Bomb Shelters". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Foulkes, Imogen (2007-02-10). "Swiss still braced for nuclear war". BBC News.

- ^ "Why Aren't There Tornado Safety Building Codes?". Live Science.

- ^ "Directory of Building Codes & Regulations: City & State Directory".

- ^ "U.S. & International Seismic Codes".

- ^ "National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program - Comparison of U.S. and Chilean Building Code Requirements and Seismic Design Practice 1985-2010".

- ^ "Drop, Cover, and Hold On – American Red Cross drill (pdf file)" (PDF).

External links[edit]

- Duck and Cover! film at YouTube

- Drop, Cover, and Hold On – American Red Cross drill (pdf file)

- Production history of the film Duck and Cover

- Prelinger Archive has Duck and Cover! available for download or streaming.

- Duck and cover at IMDb

Category:United States civil defense

Category:Disaster preparedness in the United States

Category:Disaster preparedness

Category:Safety drills

Category:Cold War terminology

Category:Nuclear warfare

Category:Articles containing video clips