User:Yerevantsi/Armenian cultural heritage in Turkey

Religious buildings[edit]

Overview[edit]

Recent research pegs the number of Armenian churches in Turkey before 1915 at around 2,300.

These numbers do not include the churches and schools in Kars and Ardahan provinces, which were not part of Turkey until 1920, and were part of Russia since 1878.

On June 18, 1987 the Council of Europe drafted a 6 point resolution which stipulates that "the Turkish government must pay attention to and take care to heed the language, culture and educational system of the Armenian Diaspora living in Turkey, simultaneously demanding an appropriate regard to the Armenian monuments that are situated in Turkey’s territory."[1]

http://www.armenianweekly.com/2011/08/01/searching-for-lost-armenian-churches-and-schools-in-turkey/

---

A survey, not in itself comprehensive, prepared in 1914 by the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople listed 2,549 religious sites under its control, including more than 200 monasteries and 1,600 churches. Many were destroyed in the process of the genocide but many more have since been vandalized, flattened or converted to mosques or barns. In contrast to Kristallnacht , where the destruction of architecture offered a warning of worse to come, the Turks have continued to remove stone by stone, the evidence of millennial of Armenian architectural and art history following the mass murder and exile of the Armenian people. It was only in the 1960s that Armenian and other architectural scholars began the politically and physically dangerous task of recording and rescuing what remains of 1,800 years of Armenian ecclesiastical heritage. A 1974 survey identified 913 remaining churches and monastic sites in Turkey in various conditions. At half of these sites the buildings had vanished utterly. Of the remainder, 252 were ruined. Just 197 survived in anything like a usable state. [2]

In the late 1980s and early '90s the travel writer William Dalrymple found evidence of the continuing destruction of Armenian historic sites. Although many sites had fallen into decay through not so benign neglect, earthquakes or peasants searching for Armenian gold supposedly hidden beneath churches, there are clear instances of deliberate destruction. [2]

He argues that the destruction accelerated in the 1970s and 80s in response to the emergence of a terrorist group, the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia, which carried out attacks against the Turkish establishment. Censorship increased. In one 1986 incident, the editor of the Turkish edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica was arrested and charged regarding a footnote that made mention of the historic Armenian kingdom of Cilicia. The book was banned. Ten years earlier, French historian J. M. Thierry was sentenced, in his absence, to three months' hard labout after being arrested for drawing a plan of an Armenian church near Van. He escaped before being sentenced. Thierry also reported that the government had sought to demolish an Armenian church in Osk Vank in 1985 but the villagers resisted, valuing it for various utilitarian uses - a granary and a stable among them. [2]

Although Dalrymple notes that the difficulties of finding unequivocally clear evidence of deliberate destruction after the fact, a number of telling examples have been discovered. A collection of five important churches at Khitzonk (now Bes Kilise), near Kars, had been officially offlimits to visitors since the genocide until the 1960s. Only the cupola of the eleventh-century St Serguis chapel remained by the time of Dalrymle's visit; its four walls had been blow out (no earthquake could cause such a damage). The remaining churches had all but vanished. Locals said the buildings had been dynamited by the army.[2]

Other shattered religious sites include Surb Karapet, partially destroyed in the 1915 massacres and then reduced to a rubble by the military target practice in the 1960s. [2]

Elsewhere some remains cling on, including the tenth-century chapel frescos at Varak Vank, now a barn. The ninth-century basilica at Dergimen Koyu, near Erzinja, is a warehouse with a huge hole smashed in the side to allow vehicles entry. The Armenian cathedral at Edessa (now Urfa), converted into a fire station in 1915, was converted again to as mosque as recently as 1994 with the remains of its ecclesiastical fittings destroyed in the process. The town is, traditionally, the first outside the Holy Land to have accepted Christianity. There are no churches in use today.[2]

The strategy of neglect of the cultural heritage of the excluded ‘other’ is a long-term policy linked to the cultural priorities of local and central governments, and might probably be seen as the continuation of the strategy of destruction in times of peace. While, at least some mosques and examples of Turkish/Islamic (indigenous) architecture are reconstructed with public funds, Christian churches or Synagogues are largely ignored by state agencies. As long as Christian or Jewish communities are present, these churches can be kept through communal efforts and even with the involvement of local municipalities. Yet, once the community is no more, as is the case in most of the Southeast of the country, the places of worship of the other are either used as stables or manufactories, are left in disrepair or converted to mosques. The few examples of conversion of churches to cultural centers and museums are mostly located in the western parts of the country, where some municipalities implement more humanistic cultural policies.

http://arsiv.setav.org/ups/dosya/13204.pdf

List of notable churches, monasteries[edit]

| Image of early 20th century | Description | Current Status | Image today |

|---|---|---|---|

Սուրբ Խաչ | |||

Մրենի տաճար | |||

|

Located in the Kars region of Turkey near the border with Armenia, the Cathedral of Mren was built in circa 638 A.D. The cathedral is a domed triple-nave basilica. | Today, access to the Cathedral is restricted due to the presence of Turkish military forces. According to an interview conducted on February 14, 2013 with Christina Maranci, an expert on the Mren Cathedral, the Cathedral is on the "verge of collapse."[3] After decades of maltreatment, the south façade has collapsed. The southern aisle has also collapsed which has created more structural issues. According to Maranci, the prospect of saving the Cathedral as the current rate is bleak. | image |

Ամենափրկիչ վանք | |||

|

Located on top of the Boztepe hill, three kilometres southeast of Trabzon, the Monastery consisted of a main church which is rectangular in form, with three naves and three apses. The main apse is pentagonal. The exact date of the Monastery's construction remains unclear. A religious community was present at the site from at least the fifteenth century, and possibly as early as the eleventh. The oldest structure in the compound is dated to 1424. In 1461 it was pillaged and destroyed by Turks. In the 16th century, the rebuilt monastery became a center of Armenian manuscript production. | In 1915, the normal functions of the monastery were interrupted when it was used as a transit camp for Armenians being deported to Syria during the Armenian Genocide.[4] After the Russian capture of Trebizond, Armenian monks returned to the monastery, and monks were there until sometime after World War I,[5] supposedly 1923.[6] A fire may have partially ruined the site at a later date. By the 1950s, the main church was roofless and most of the bell-tower had been destroyed. A farm now utilizes the remaining buildings of the Kaymaklı monastery. | |

Հոռոմոս | |||

|

The Monastery of Horomos is a prominent 10th century Armenian monastic complex, about 15 kilometers northeast of Ani in historical Armenia (now in Turkey). It is one of the most important religious and cultural centers within the Kingdom of Ani, and was founded during the reign of King Abas the first (943-953). The Monasteries have undergone a series of renovations starting from 1788 with further renovations in 1852, 1868, 1871, and 1878.[7] The Monasteries remained in operation until 1920.[7] | Some time after 1965, the Monastic Complex of Horomos was partly destroyed. The tomb of King Ashot III (953-977) which had survived at least up to 1920 has not been found. Various structures of the Monasteries have vanished, and most of the surviving walls have been stripped of their facing masonry.[7] The dome of the Church of the St. John collapsed in the 1970s.[8] The site lies next to the Armenian border and gaining permission to access the monastery is restricted.[7] | |

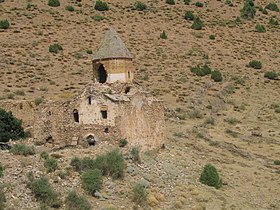

Կարմրավանք | |||

|

The Monastery is located in the Vaspurakan region around Lake Van. It is located 12 kilometers west-northwest of Akhtamar Island. It was founded by King Gagik I (908-943) of the Artsruni dynasty.[9] | The Monastery is heavily damaged. The surrounding defensive walls are in ruins. The dome is completely ruined. |

|

Վարզահան | |||

|

There is no precise date as to when the Varzahan Monastary was built. However, churches and monasteries with similar architectural characteristics were built in the eleventh century.[10] It is also noted that the province of Bayburt had an Armenian mayor.[10] The church was eight-sided externally and each side was approximately 4.7 metres wide with walls that were about 0.95 metres thick.[10] | The Monastery was destroyed sometime around the 1920s to the mid 1950s.[10][11] Nothing now remains of the church.[10] It is believed that the Monastery had already been extensively damaged after the towns Armenian population was subjected to massacre in the 18th century.[12] | |

Անիի Մայր Տաճար | |||

|

The Cathedral of Ani also known as the The Holy Virgin Cathedral was an Armenian church[13] completed in 1001 (or possibly 1010) by the architect Trdat in the ruined ancient Armenian capital of Ani,[14] located in what is now the extreme eastern tip of Turkey, on the border with modern Armenia. It offers an example of a domed cruciform church within a rectangular plan. The Cathedral of Ani is 100 feet (30,5 meters) long and 65 feet (19,8 meter) wide,[15] unusually large by Armenian standards, which is possible by supporting the dome on four piers of clustered columns, one of the features of the architecture that was to be very common in Western architecture. The roofs are stone vaulted throughout. Tall blind arcades decorate the external walls, including the ruined drum. There is carved relief decoration around several windows. There are three entrances, for the prince (south), the patriarch (north) and the people (west); each originally had a porch.[16] | Following the Seljuk Turkish victories in eastern Anatolia, Sultan Alp Arslan in 1064 took down the crosses from the cathedral after entering the city; in 1071 it was turned into a mosque.[17]

The dome and the drum supporting it are now missing, having collapsed in an earthquake in 1319. A further earthquake in 1988 caused the collapse of the north-west corner, and weakened all of the west facade.[16] Currently, there is a risk that the entire western facade will collapse.[16] On September 19, 2010, the Armenian Cathedral of the Holy Cross at Lake Van saw its first Christian mass in 95 years. A group of Turkish nationalists responded on October 1, 2010, by gathering at the Cathedral of Ani to say Muslim prayers led by Devlet Bahçeli, head of the Nationalist Movement Party.[18][19] |

|

The premeditated destruction of objects of Armenian cultural, religious, historical and communal heritage was yet another key purpose of both the genocide itself and the post-genocidal campaign of denial. Armenian churches and monasteries were destroyed or changed into mosques, Armenian cemeteries flattened, and, in several cities (e.g. Van), Armenian quarters were demolished.[20]

Aside from the deaths, Armenians lost their wealth and property without compensation.[21] Businesses and farms were lost, and all schools, churches, hospitals, orphanages, monasteries, and graveyards became Turkish state property.[21] In January 1916, the Ottoman Minister of Commerce and Agriculture issued a decree ordering all financial institutions operating within the empire's borders to turn over Armenian assets to the government.[22] It is recorded that as much as 6 million Turkish gold pounds were seized along with real property, cash, bank deposits, and jewelry.[22] The assets were then funneled to European banks, including Deutsche and Dresdner banks.[22]

After the end of World War I, Genocide survivors tried to return and reclaim their former homes and assets, but were driven out by the Ankara Government.[21]

In 1914, the Armenian Patriarch in Constantinople presented a list of the Armenian holy sites under his supervision. The list contained 2,549 religious places of which 200 were monasteries while 1,600 were churches. In 1974 UNESCO stated that after 1923, out of 913 Armenian historical monuments left in Eastern Turkey, 464 have vanished completely, 252 are in ruins, and 197 are in need of repair (in stable conditions).[23][24]

- Arter

- Banak

- Diyarbakir

- Saint Hakob of Akori Monastery

- St. Marineh Church, Mush

- Tekor Basilica

- Bagnayr Monastery

- St. Hovhannes Church of Bagrevand

sources[edit]

Reaction[edit]

http://assembly.coe.int/ASP/Doc/XrefViewHTML.asp?FileID=11851&Language=EN

http://rules.house.gov/Media/file/PDF_112_1/Suspension%20bills/HRes3061209.pdf

On June 18, 1987, the European Parliament, with the initiative of the Greek MPs, formally recognized the Armenian Genocide.[25]

- Calls for fair treatment of the Armenian minority in Turkey as regards their identity, language, religion, culture and school system, and makes an emphatic plea for improvements in the care of monuments and for the maintenance and conservation of the Armenian religious architectural heritage in Turkey and invites the Community to examine how it could make an appropriate contribution;

- Considers that the protection of monuments and the maintenance and conservation of the Armenian religious architectural heritage in Turkey must be regarded as part of a wider policy designed to preserve the cultural heritage of all civilizations which have developed over the centuries on present-day Turkish territory and, in particular, that of the Christian minorities that formed part of the Ottoman Empire;

References[edit]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

cultural123was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f Bevan, Robert (2006). "Chapter 2. Cultural Cleansing: Who Remembers the Armenians?". The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. London: Reaktion. ISBN 9781861896384.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapter= - ^ Kasbarian, Lucine (February 14, 2013). "A Cathedral on the Verge of Collapse: The Campaign to Save Mren". Hetq.am. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ Bryer, Byzantine Monuments and Topography of the Pontos, pp. 208-211

- ^ Ballance, The Byzantine Churches of Trebizond, p. 169

- ^ Darke, Guide to Eastern Turkey and the Black Sea Coast, p. 327

- ^ a b c d "Destruction of Horomos Monastery". Asbarez. August 27, 2003. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "THE MONASTERY OF HOROMOS". VirtualANI. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. (2000), "Van in This World; Paradise in the Next: The Historical Geography of Van/Vaspurakan", in Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.), Armenian Van/Vaspurakan, Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces, Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers, p. 27, OCLC 44774992

- ^ a b c d e "Varzahan". VirtualAni. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Revue des Études Arméniennes, volume 2, 1965, page 184

- ^ Revue des Études Arméniennes, volume 2, 1965, page 184

- ^ New international encyclopedia: Volume 2 - Page 139

- ^ The Architect Trdat Building Practices and Cross-Cultural Exchange in Byzantium and Armenia by Christina Maranci - p.294

- ^ History of Religious Architecture, Ernest H. Short, page 71

- ^ a b c "The Cathedral of Ani". VirtualAni.

- ^ Fortescue, Adrian (2001). Lesser Eastern Churches. Gorgias Press. p. 387. ISBN 0-9715986-2-2.

- ^ "Turkish nationalists rally in Armenian holy site at Ani". BBC News Online. 1 October 2010.

- ^ WMF

- ^ Bevan, Robert. The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. Reaktion Books, 2007, pp. 52–60.

- ^ a b c Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William S. (2009). A Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. New York: Routledge. p. 58. ISBN 0-203-89043-4.

- ^ a b c "Armenian Genocide Descendants File Class Action against Deutsche Bank and Dresdner Bank Announces Kabateck Brown Kellner LLP". Business Wire. May 6, 2010. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ Cultural Genocide in The Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute.

- ^ Bevan, Robert, The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War, Chicago, 2006.

- ^ "European Parliament Resolution". Armenian National Institute. 18 June 1987. Retrieved 30 June 2013.