Vaquita

| Vaquita Temporal range: [1]

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Phocoenidae |

| Genus: | Phocoena |

| Species: | P. sinus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Phocoena sinus Norris & McFarland, 1958

| |

| |

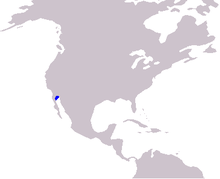

| Vaquita range | |

The vaquita (/vəˈkiːtə/ və-KEE-tə; Phocoena sinus) is a species of porpoise endemic to the northern end of the Gulf of California in Baja California, Mexico. Averaging 150 cm (4.9 ft) (females) or 140 cm (4.6 ft) (males) in length, it is the smallest of all living cetaceans. The species is currently on the brink of extinction, and currently listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN Red List; the steep decline in abundance is primarily due to bycatch in gillnets from the illegal totoaba fishery.[4][5]

Taxonomy

The vaquita was defined as a species by two zoologists, Kenneth S. Norris and William N. McFarland, in 1958 after studying the morphology of skull specimens found on the beach.[6] It was not until nearly thirty years later, in 1985, that fresh specimens allowed scientists to describe their external appearance fully.[7]

The genus Phocoena comprises four species of porpoise, most of which inhabit coastal waters (the spectacled porpoise is more oceanic). The vaquita is most closely related to Burmeister's porpoise (Phocoena spinipinnis) and less so to the spectacled porpoise (Phocoena dioptrica), two species limited to the Southern Hemisphere. Their ancestors are thought to have moved north across the equator more than 2.5 million years ago during a period of cooling in the Pleistocene.[7] Genome sequencing from an individual captured in 2017 indicates that the ancestral vaquitas had already gone through a major population bottleneck in the past, which may explain why the few remaining individuals are still healthy despite the very low population size.[8]

"Vaquita" is Spanish for "little cow".[9]

Description

The smallest living species of cetacean, the vaquita can be easily distinguished from any other species in its range. It has a small body with an unusually tall, triangular dorsal fin, a rounded head, and no distinguished beak. The coloration is mostly grey with a darker back and a white ventral field. Prominent black patches surround its lips and eyes.[7] Sexual dimorphism is apparent in body size, with mature females being longer than males and having larger heads and wider flippers.[7][10] Females reach a maximum size of about 150 cm (4.9 ft), while males reach about 140 cm (4.6 ft).[7] Dorsal fin height is greater in males than in females.[10] They are also known to weigh around 27 kg (60 lb) to 68 kg (150 lb). This makes them one of the smallest species in the porpoise family. [11]

Distribution and habitat

Vaquita habitat is restricted to a small portion of the upper Gulf of California (also called the Sea of Cortez), making this the smallest range of any marine mammal species. They live in shallow, turbid waters of less than 150 m (490 ft) depth.[5] Vaquitas inhabit murky warm waters within 26 kilometres (16 mi) of the shoreline since there is high food availability and a strong tidal mix. Since they are able to survive in shallow waters, their triangle-shaped dorsal fin sticks out above water and they are commonly mistaken for dolphins (Center for Biological Diversity, n.d).

Diet

Vaquitas are generalists, foraging on a variety of demersal fish species, crustaceans, and squids, though benthic fish such as grunts and croakers make up most of the diet.[5]

Social behavior

Vaquitas are generally seen alone or in pairs, often with a calf, but have been observed in small groups of up to 10 individuals.[5]

Little is known about the life history of this species. Life expectancy is estimated at about 20 years and age of sexual maturity is somewhere between 3 and 6 years of age.[12] While an initial analysis of stranded vaquitas estimated a two-year calving interval, recent sightings data suggest that vaquitas can reproduce annually.[12][13] It is thought that vaquitas have a polygynous mating system in which males compete for females. This competition is evidenced by the presence of sexual dimorphism (females are larger than males), small group sizes, and large testes (accounting for nearly 3% of body mass).[12]

Population status

Because the vaquita was only fully described in the late 1980s, historical abundance is unknown.[14] Since 1983, all confirmed specimens, records, and sightings of P. sinus were evaluated. There were 45 records of P. sinus that were collected by skeletal remains, photographs, and sightings in 1983.[15] The first comprehensive vaquita survey throughout their range took place in 1997 and estimated a population of 567 individuals.[16] By 2007 abundance was estimated to have dropped to 150.[17] Population abundance as of 2018 was estimated at less than 19 individuals.[18] Given the continued rate of bycatch and low reproductive output from a small population, it is estimated that there are fewer than 10 vaquitas alive as of February 2022.[19][18][20]

Reproduction

Vaquitas reach sexual maturity from three to six years old. Vaquitas have synchronous reproduction, suggesting that calving span is greater than a year. Their pregnancies last from 10 to 11 months. Vaquitas give birth about every other year to a single calf. They give birth between the months of February and April.[21][22]

Threats

Fisheries bycatch

The drastic decline in vaquita abundance is the result of fisheries bycatch in commercial and illegal gillnets, including fisheries targeting the now-endangered Totoaba, shrimp, and other available fish species.[4][14] Despite government regulations, including a partial gillnet ban in 2015 and establishment of a permanent gillnet exclusion zone in 2017, illegal totaoba fishing remains prevalent in vaquita habitat, and as a result the population has continued to decline.[18] The vaquita is the most critically endangered marine mammal, with fewer than 19 remaining in the wild.[23] First described in 1958, the vaquita has been in rapid decline for more than 20 years resulting from inadvertent deaths due to the increasing use of large-mesh gillnets.[23]

In 2021, the Mexican government eliminated a "no tolerance" zone in the Upper Gulf of California and opened it up to fishing.[24]

Other threats

Given their proximity to the coast, vaquitas are exposed to habitat alteration and pollution from runoff. Bycatch is the single biggest threat to the survival of the few remaining vaquita.[20] A series of simulations in a 2022 study indicate that the species has a chance to survive and recover if all bycatch is halted, despite the presence of other threats.[25] Exposure to toxic compounds has also had a deleterious effect on vaquitas.[26]

Predation on vaquita by sharks has also been reported from fishermen, who have seen whole or parts of individuals in the stomachs of caught sharks, although no quantitative analysis is readily available.[27][28] However, the biggest threat still towards vaquita are fisheries. Northern fishing fleets have had an indirect positive impact mainly on marine mammals, because fishing on predators like sharks reduces its predatory negative impact on those groups. Although the predation of sharks towards vaquita do result in a decline in population and is seen as an alternate threat, northern fishing fleets also negatively impact this small marine mammal because the negative influence of incidental catch is greater than the positive influence of predation reduction by shark fisheries.[28]

Populations that experience a sudden decline in numbers are often more vulnerable to other threats in the future due to a bottleneck of genetic diversity within the reduced population. The reduced gene pool lowers the rate of adaptation and increases the rate of inbreeding; however, a 2022 study on the genetic diversity of the vaquita suggests that the marine mammal’s historically small population ensures it is unlikely to greatly suffer from inbreeding depression.[25]

Attempts to start a population in captivity have proved to be more threatening to the population than helpful. A November 2017 effort ended up traumatizing and killing one female vaquita, as well as invoking unnecessary stress onto a juvenile.[29]

Conservation status

The vaquita is listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List.[5] It is considered the most endangered marine mammal in the world.[18][5]

The species is also protected under the US Endangered Species Act, the Mexican Official Standard NOM-059 (Norma Oficial Mexicana), and Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).[30]

Conservation efforts

The Mexican government, international committees, scientists, and conservation groups have recommended and implemented plans to help reduce the rate of bycatch, enforce gillnet bans, and promote population recovery.

Mexico launched a program in 2008 called PACE-VAQUITA in an effort to enforce the gillnet ban in the Biosphere Reserve, allow fishermen to swap their gillnets for vaquita-safe fishing gear, and provide economic support to fishermen for surrendering fishing permits and pursuing alternative livelihoods.[31] Despite the progress made with legal fishermen, hundreds of poachers continued to fish in the exclusion zone.

With continued illegal totoaba fishing, which is largely motivated by sales to the Chinese market where it is used in traditional medicine, and uncontrolled bycatch of vaquitas, the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA) recommended that some vaquitas be removed from the high-density fishing area and be relocated to protected sea pens. This effort, called VaquitaCPR,[32] captured two vaquitas in 2017: One was later released and the other died shortly after capture after both suffered from shock.[33]

Local and international conservation groups, including Museo de Ballena and Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, are working with the Mexican Navy to detect fishing in the Refuge Area and remove illegal gillnets.[31] In March 2020, the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) announced a ban on imported Mexican shrimp and other seafood caught in vaquita habitat in the northern Gulf of California.[34]

In response to the dire circumstances facing the vaquita as by-catch of the illegal totoaba trade, in 2017 Earth League International (ELI) commenced an investigation and intelligence gathering operation called Operation Fake Gold, during which the entire illicit totoaba maw (swim bladder) international supply chain, from Mexico to China, has been mapped and researched. Thanks to the confidential data that ELI shared with the Mexican authorities, in November 2020, a series of important arrests were made in Mexico.[35]

To date, efforts have been unsuccessful in solving the complex socioeconomic and environmental issues that affect vaquita conservation and the greater Gulf of California ecosystem. Necessary action includes habitat protection, resource management, education, fisheries enforcement, alternative livelihoods for fishermen, and raising awareness of the vaquita and associated issues.[5]

The Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) announced on February 27, 2021, that it may reduce the protected area for the vaquita in the Sea of Cortés as there are only ten of the porpoises left and it may never recuperate its historical range.[36]

Beginning in July 2022, the Mexican government placed 193 concrete blocks in the Gulf of California no-tolerance zone, intended to allow the detection of nets by acoustic sonar and prevent further entrapment of vaquitas.[37]

Consumers

Roughly 80% of shrimp caught in the northern end of the Gulf of California, which has a high aquatic mammal bycatch rate, is consumed in the United States. As such, U.S. consumers of this shrimp are likely contributing to the vaquita extinction crisis. The Marine Animal Protection Act of 1972, which forbids foreign fishers from exporting seafood with high levels of marine mammal bycatch, may allow for better efforts to preserve endangered vaquitas.[38]

References

- ^ "Phocoena sinus". Fossilworks Database. John Alory. Retrieved 17 December 2021 – via fossilworks.org.

- ^ Rojas-Bracho, L.; Taylor, B.L. (2017). "Phocoena sinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T17028A50370296. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T17028A50370296.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ a b Rojas-Bracho, Lorenzo; Reeves, Randall R. (3 July 2013). "Vaquitas and gillnets: Mexico's ultimate cetacean conservation challenge". Endangered Species Research. 21 (1): 77–87. doi:10.3354/esr00501. ISSN 1863-5407.

- ^ a b c d e f g Taylor, Barbara; Rojas-Bracho, Lorenzo (20 July 2017). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Vaquita". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Norris, Kenneth S.; McFarland, William N. (20 February 1958). "A New Harbor Porpoise of the Genus Phocoena from the Gulf of California". Journal of Mammalogy. 39 (1): 22–39. doi:10.2307/1376606. ISSN 0022-2372. JSTOR 1376606.

- ^ a b c d e Brownell, Robert L.; Findley, Lloyd T.; Vidal, Omar; et al. (1987). "External Morphology and Pigmentation of the Vaquita, Phocoena Sinus (cetacea: Mammalia)". Marine Mammal Science. 3 (1): 22–30. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1987.tb00149.x. ISSN 1748-7692.

- ^ Casanueva, Agustín B. Ávila (11 July 2020). "Secuenciar el genoma de la vaquita marina es la esperanza para su conservación". TecReview (in Mexican Spanish). Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Saying Adios to the Vaquita". Saving Earth | Encyclopedia Britannica. 11 April 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ a b Torre, Jorge; Vidal, Omar; Brownell, Robert L. (October 2014). "Sexual dimorphism and developmental patterns in the external morphology of the vaquita, Phocoena sinus". Marine Mammal Science. 30 (4): 1285–1296. doi:10.1111/mms.12106.

- ^ Fisheries, NOAA. “Vaquita.” NOAA, 29 Dec. 2021, https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/vaquita.

- ^ a b c Hohn, A. A.; Read, A. J.; Fernandez, S.; Vidal, O.; Findley, L. T. (1996). "Life history of the vaquita, Phocoena sinus (Phocoenidae, Cetacea)". Journal of Zoology. 239 (2): 235–251. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1996.tb05450.x. ISSN 1469-7998.

- ^ Taylor, Barbara L.; Wells, Randall S.; Olson, Paula A.; et al. (2019). "Likely annual calving in the vaquita, Phocoena sinus: A new hope?". Marine Mammal Science. 35 (4): 1603–1612. doi:10.1111/mms.12595. ISSN 1748-7692. S2CID 91403217.

- ^ a b Rojas‐Bracho, Lorenzo; Reeves, Randall R.; Jaramillo‐Legorreta, Armando (2006). "Conservation of the vaquita Phocoena sinus". Mammal Review. 36 (3): 179–216. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2006.00088.x. ISSN 1365-2907.

- ^ "Shibboleth Authentication Request". login.proxy.cc.uic.edu. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1986.tb00137.x. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ Jaramillo‐Legorreta, Armando M.; Rojas‐Bracho, Lorenzo; Gerrodette, Tim (1999). "A New Abundance Estimate for Vaquitas: First Step for Recovery1". Marine Mammal Science. 15 (4): 957–973. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00872.x. ISSN 1748-7692.

- ^ Jaramillo-Legorreta, Armando; Rojas-Bracho, Lorenzo; Brownell, Robert L.; et al. (15 November 2007). "Saving the Vaquita: Immediate Action, Not More Data". Conservation Biology. 21 (6): 071117012342001––. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00825.x. ISSN 0888-8892. PMID 18173491. S2CID 7034303.

- ^ a b c d Jaramillo-Legorreta, Armando M.; Cardenas-Hinojosa, Gustavo; Nieto-Garcia, Edwyna; et al. (2019). "Decline towards extinction of Mexico's vaquita porpoise (Phocoena sinus)". Royal Society Open Science. 6 (7): 190598. Bibcode:2019RSOS....690598J. doi:10.1098/rsos.190598. PMC 6689580. PMID 31417757.

- ^ Canon, Gabrielle (12 February 2022). "The tiny vaquita porpoise now numbers less than 10. Can they be saved?". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Report of the Eleventh meeting of the Comité Internacional para la Recuperación de la Vaquita (CIRVA)" (PDF). iucn-csg.org. February 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

...analysis indicated that only about 10 vaquitas remained alive in 2018 (with a 95% chance of the true value being between 6 and 22).

- ^ Fisheries, NOAA (20 October 2021). "Vaquita | NOAA Fisheries". NOAA. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ Hohn, A. A.; Read, A. J.; Fernandez, S.; Vidal, O.; Findley, L. T. (June 1996). "Life history of the vaquita,Phocoena sinus(Phocoenidae, Cetacea)". Journal of Zoology. 239 (2): 235–251. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1996.tb05450.x. ISSN 0952-8369.

- ^ a b Morin, Phillip A.; Archer, Frederick I.; Avila, Catherine D.; Balacco, Jennifer R.; Bukhman, Yury V.; Chow, William; Fedrigo, Olivier; Formenti, Giulio; Fronczek, Julie A.; Fungtammasan, Arkarachai; Gulland, Frances M. D. (20 November 2020). "Reference genome and demographic history of the most endangered marine mammal, the vaquita". Molecular Ecology Resources. 21 (4): 1008–1020. doi:10.1111/1755-0998.13284. ISSN 1755-098X. PMC 8247363. PMID 33089966.

- ^ "'Mismanaged to death': Mexico opens up sole vaquita habitat to fishing". Mongabay Environmental News. 16 July 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ a b Robinson, Jacqueline A.; Kyriazis, Christopher C.; Nigenda-Morales, Sergio F.; Beichman, Annabel C.; Rojas-Bracho, Lorenzo; Robertson, Kelly M.; Fontaine, Michael C.; Wayne, Robert K.; Lohmueller, Kirk E.; Taylor, Barbara L.; Morin, Phillip A. (6 May 2022). "The critically endangered vaquita is not doomed to extinction by inbreeding depression". Science. 376 (6593): 635–639. doi:10.1126/science.abm1742. ISSN 0036-8075. S2CID 248542094.

- ^ Lam, Su Shiung; Chew, Kit Wayne; Show, Pau Loke; et al. (1 November 2020). "Environmental management of two of the world's most endangered marine and terrestrial predators: Vaquita and cheetah". Environmental Research. 190: 109966. Bibcode:2020ER....190j9966L. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2020.109966. ISSN 0013-9351. PMID 32829186. S2CID 221282339.

- ^ Torre, Jorge; Vidal, Omar; Brownell, Robert L. (22 January 2014). "Sexual dimorphism and developmental patterns in the external morphology of the vaquita, Phocoena sinus". Marine Mammal Science. 30 (4): 1285–1296. doi:10.1111/mms.12106. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ a b Díaz-Uribe, J. Gabriel; Arreguín-Sánchez, Francisco; Lercari-Bernier, Diego; et al. (April 2012). "An integrated ecosystem trophic model for the North and Central Gulf of California: An alternative view for endemic species conservation". Ecological Modelling. 230: 73–91. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2012.01.009. ISSN 0304-3800.

- ^ Pennisi, Elizabeth (November 2017). "Update: After death of captured vaquita, conservationists call off rescue effort".

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Vaquita". iucn-csg.org. IUCN – SSC Cetacean Specialist Group. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Rescue Efforts". VaquitaCPR.org. 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Rojas-Bracho, L; Gulland, FMD; Smith, CR; et al. (11 January 2019). "A field effort to capture critically endangered vaquitas Phocoena sinus for protection from entanglement in illegal gillnets". Endangered Species Research. 38: 11–27. doi:10.3354/esr00931. ISSN 1863-5407.

- ^ "U.S. Government Expands Mexican Seafood Ban to Save Vaquita Porpoise". NRDC.org. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Vaquita: Earth League International's investigation triggers arrests". earthleagueinternational.org. Earth League International. 28 November 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ "Mexico may reduce protection area for endangered porpoise". news.yahoo.com. AP. 27 February 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ "The last eight vaquitas in the Gulf of California are to be saved". The Yucatan Times. 9 October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Dunch, Victoria (1 August 2019). "Saving the vaquita one bite at a time: The missing role of the shrimp consumer in vaquita conservation". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 145: 583–586. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.06.043. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 31590827. S2CID 198269466.

Further reading

- Alcántara, A. (December 2017). "Vaquita: The Business of Extinction (article and 25-min. documentary video)". CNN. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- Bessesen, Brooke (September 2018). Vaquita: Science, Politics, and Crime in the Sea of Cortez. Island Press. ISBN 978-1-61091-932-6.

- Vance, E. (August 2017). "Goodbye, Vaquita: How Corruption and Poverty Doom Endangered Species". Scientific American. 317 (2): 36–45. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0817-36. PMID 29565922.

- Einhorn, Catrin; Ramos, Fred (23 November 2021). "Here's the Next Animal That Could Go Extinct". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

External links

To learn more about the vaquita and conservation efforts visit:

- ¡Viva Vaquita! – a non-profit organization dedicated to preventing the extinction of the vaquita

- Vaquita fact sheet from NOAA Fisheries

- The Vaquita and the Totoaba – web site for the Wild Lens Collective of film makers' outreach campaign about the vaquita's extinction crisis

- "Souls of the Vermilion Sea", a 30-minute documentary about the local community where the vaquita is found and why its population has declined

- "Sea of Shadows", a full-length 2019 documentary produced by Leonardo DiCaprio on the effort to rescue the vaquita from extinction

- Voices in the Sea – sounds of the vaquita

- VaquitaMarina.org, a Baja California Sur-based vaquita conservation group

- Operation Milagro III, Sea Shepherd Conservation Society's operation to protect the vaquita

- Porpoise Conservation Society

- Society for Marine Mammalogy

- Operation Fake Gold, [Earth League International]