Vienna Museum

Vienna Museum main building on Karlsplatz | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Location | Vienna, Austria |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 48°11′56.0″N 16°22′23.2″E / 48.198889°N 16.373111°E |

The Vienna Museum (German: Wien Museum or Museen der Stadt Wien) is a group of museums in Vienna consisting of the museums of the history of the city. In addition to the main building in Karlsplatz and the Hermesvilla, the group includes numerous specialised museums, musicians' residences and archaeological excavations.

The permanent exhibit of art and the historical collection on the history of Vienna include exhibits dating from the Neolithic to the mid-20th century. The emphasis is on the 19th century, for example works by Gustav Klimt. In addition, the Vienna Museum hosts a variety of special exhibitions.

History[edit]

Originally known as the Historical Museum of the City of Vienna (Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien), its existence dates back to 1887, and until 1959 was located in the Vienna Town Hall (Rathaus). The first plans for a city museum on Karlsplatz date back to the beginning of the 20th century; one of proposed plans were drawn by the renowned Jugendstil architect Otto Wagner. However, not least because of two world wars, the building of the museum was postponed for several decades.

In 1953, the City Council of Vienna passed a resolution to honour Austrian president and former mayor Theodor Körner, on the occasion of his 80th birthday by making the museum building a reality. A design contest was organised, in which 13 architects were specifically invited to take part (including Clemens Holzmeister, Erich Boltenstern and Karl Schwanzer) but which was open to any other entrants. Designs were evaluated by a jury which was chaired by the architect Franz Schuster and whose other members were the architects Max Fellerer and Roland Rainer, the Vienna Director of Building, the Director of City Collections, Franz Glück, the Head of the City Department of Regulations and the Head of the Department of Architecture.

80 contestants took part and submitted a total of 96 designs. The jury awarded Oswald Haerdtl fourth place, but he was subsequently "off-handedly" contracted to design the building, which was executed in an unassuming contemporary modern style. Haertl was also responsible for the interior design, down to the furnishing of the director's office. The museum opened on 23 April 1959 as the first newly built museum of the Second Republic, and remained the only such for decades.[1][2]

The Historical Museum repeatedly distinguished itself with its exhibitions. In 1985, under director Robert Waissenberger, it presented the Jugendstil exhibition Traum und Wirklichkeit (Dream and Reality) at the Vienna Künstlerhaus on the opposite side of the square; with more than 600,000 visitors, one of the most successful exhibitions ever held in Vienna.

In 2000, the courtyard was roofed over. In 2003, under the direction of Wolfgang Kos, the museums of the City of Vienna were united under the umbrella name of Vienna Museum and the Historical Museum was renamed Vienna Museum. In early 2006, the foyer was renovated and in addition, new exhibition space was created in what had been a storage area.

The main building of the museum presents a mix of historical and art exhibits with the intent of offering the visitor a cross section of the development of the city, from its beginnings in the Neolithic through the Roman camp of Vindobona up to the 20th century. In addition to the permanent exhibits, there are frequent special exhibitions.

A memorandum of understanding and cooperation was signed in January 2000 with the Nagoya City Museum, establishing it as a partner museum.[3]

Highlights of 50 years, 1958–2008[edit]

In autumn 2008, to celebrate its 50 years in the Karlsplatz building, the Vienna Museum published a list of highlights of its history,[4] including the following:

- 23 April 1959: Formal opening of the Historical Museum building and of the first special exhibition, on Hieronymus Löschenkohl, by President Adolf Schärf

- 1960: Exhibition on the Vienna Municipal Armoury

- 1961: Opening of the permanent exhibition on the Art and History of Vienna

- 1963: Exhibition on Otto Wagner: The Architects' Oeuvre

- 1964: Opening of Prater Museum; exhibition on Vienna circa 1900

- 1968: Exhibition on Joseph Olbrich

- 1969: Exhibition on Vienna 1800–1850: Empire and Biedermeier

- 1970: Opening of Beethoven memorial in Heiligenstadt

- 1973: Exhibition on 1850–1900: World of the Ringstraße

- 1974–1986: Free entrance to the museum and its annexes

- 1977: Exhibition on Vindobona: The Romans in the Vienna area

- 1979: Renovated Hermesvilla becomes a unit of the Museums of the City of Vienna; one of the demolition-threatened Stadtbahn pavilions by Otto Wagner in Karlsplatz is transferred to the museum

- 1980: Exhibition on The Vienna Coffeehouse: From the beginnings to between the wars

- 1981: 106,000 people visit the Egon Schiele exhibition with works from the Serge Sabarsky collection

- 1982: Neidhart Frescoes become a new museum annexe

- 1983: First large-scale exhibition in the Künstlerhaus on The Turks at the gates of Vienna, curated by Hans Hollein

- 1985: Large-scale exhibition on Dream and Reality: Vienna 1870–1930, curated by Hans Hollein; a record-breaking 622,000 visitors

- 1986: Exhibition on Elisabeth of Austria: Loneliness, power and freedom, at Hermesvilla

- 1987: Exhibition on Biedermeier and Vormärz in the Künstlerhaus, curated by Boris Podrecca

- 1989: Exhibition on Arnulf Rainer which travels on to New York City and Chicago

- 1993: Exhibition on Red Vienna

- 1995: Exhibition on Hans Hollein

- 1997: Exhibition on Franz Schubert, curated by Hermann Czech

- 1999: Exhibitions on Rebuilt Vienna 1800–2000: Projects for the metropolis; Johann Strauß: Thunder and lightning

- 2000: Atrium extension and roofing over by Dimitris Manikas; exhibition on Hans Makart: Painter prince, at Hermesvilla. Cooperation established with Nagoya City Museum.

- 2002: Separation of the Historical Museum of the City of Vienna from city government

- 2003: Renamed Vienna Museum

- 2004: Exhibition on Gastarbajteri: 40 years of worker migration; large-scale exhibition on Old Vienna: the city that never was (Künstlerhaus)

- 2006: Renovation by BMW Architekten: new entrance area, additional exhibition space

- 2007: Exhibitions on In the Tavern; At the Bottom: The discovery of misery

- 2008: Opening of the Museum of the Romans in Hoher Markt

- 2009: Reopening of renovated Haydn House

- 2009-2010: Large-scale exhibition at the Künstlerhaus: Battle for the City: Politics, art and everyday life circa 1930

- 2018: Exhibition on Otto Wagner

Collection highlights[edit]

-

Vienna Battle 1683 by Frans Geffels

-

Loge im Sofiensaal by Josef Engelhart

-

Family portrait of the imperial family by Leopold Fertbauer

-

Arthur Roessler by Egon Schiele

-

Court Ball at the Hofburg by Wilhelm Gause

-

Woman in a Yellow Dress (1899 )by Max Kurzweil

-

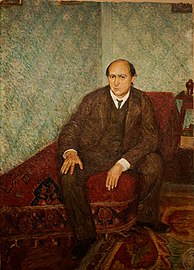

Arnold Schönberg by Richard Gerstl

-

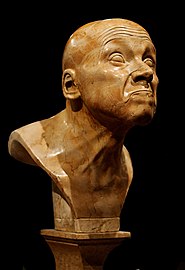

Simplicity of the highest degree by Franz Xaver Messerschmidt

-

Portrait of Emilie Louise Flöge by Gustav Klimt

-

Self-portrait by Anton Faistauer

Hermesvilla[edit]

Since 1971, exhibitions have been presented in the Hermesvilla, a former imperial residence in the Lainzer Tiergarten in the west of Vienna which Emperor Franz Joseph had built for his wife Empress Elisabeth in 1882–86. Under former mayor Bruno Marek, the building was restored by the Association of Friends of the Hermesvilla and subsequently taken over by the city. The permanent exhibition is dedicated to the history of the building and the imperial couple, who spent a few days there each year until Elisabeth's death. In addition, special exhibitions are mounted on a wide variety of themes in cultural history.

Special museums[edit]

Otto Wagner Pavilion on Karlsplatz[edit]

Since 2005, a permanent exhibition on the life and work of Otto Wagner has been on show in this former Vienna Stadtbahn building.

The building was constructed in 1898 as one of a pair of Jugendstil pavilions on either side of the square as part of the construction of the Stadtbahn in the 1890s; Otto Wagner was the contract designer of the system. During the planning in the 1960s for the new Vienna U-Bahn nodal station at Karlsplatz, the two pavilions were saved from demolition, dismantled, restored, and put back in place in 1977 after completion of the construction work in the square. They no longer serve any transport purpose.

Otto Wagner Hofpavillon at Hietzing[edit]

The Pavillon des k.u.k. Allerhöchsten Hofes (Pavilion of the royal and imperial court) in Hietzing near Schönbrunn Palace was built in 1899 to Otto Wagner's design as a special station for the use of the Emperor and members of his court when using the Stadtbahn. It was not included in the original plans for the Stadtbahn, but Wagner began construction on his own initiative and was finally able to win over the Minister for Railways, Heinrich von Wittek. In contrast to the other Stadtbahn stations, this pavilion with its cupola has baroque elements, which could be interpreted as a sign of respect for the Emperor on the architect's part. It was built at the inbound end of the platform at the Hietzing station, which opened in 1898; originally there were steps linking it to the public platforms.

The Emperor is only known to have used the station on two occasions: in 1899 when he opened the lower Vienna Valley line on the Stadtbahn (between Meidling Hauptstraße and Hauptzollamt) and in April 1902. Today the imperial waiting room and study and other rooms in the building are on permanent display.

Prater Museum[edit]

The Prater Museum is located in the Prater park, in the planetarium building near the Ferris wheel. It presents the history of Vienna's largest amusement park, the Wurstelprater, with exhibits such as an old mechanical fortune-teller and coverage of dark rides and sideshows. The museum was founded in 1933 by the teacher and local historian Hans Pemmer in his home and donated in 1964 to the City of Vienna, which built the present museum.[5]

Clock Museum[edit]

The Vienna Clock Museum in the Palais Obizzi in the Innere Stadt, founded in 1917, is one of the most important of its kind on Europe. On the ground floor are displayed the collections of the museum's first and long-time director, Rudolf Kaftan, and of the poet Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach. During the Second World War, the "House of Ten Thousand Clocks", as it is also known, was closed and attempts were made to disperse the valuable clocks for safety to various castles in Lower Austria, with only partial success. After the war, work began on rebuilding the collection; thanks to funds from the City of Vienna and private donations, it has been possible to add a few additional rarities to the collection.[6]

Fashion collection library[edit]

The Vienna Museum has a fashion collection in Meidling, adjacent to the Vienna School of Fashion at Schloss Hetzendorf. This is not open to the public, but the public may use the attached library, consisting of over 12,000 volumes and numerous periodicals, photographs and approximately 3,000 engravings on the subject of fashion.

Musicians' residences[edit]

The Vienna Museum includes numerous residences in which notable composers lived, were born and died, which are largely in original condition and intended to afford the visitor insight into the artists' everyday lives. Exhibits include music manuscripts, but also objects they used.

Mozart residence[edit]

The rooms in the Mozarthaus Vienna in Domgasse, near St. Stephen's Cathedral, are the only one of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's residences in Vienna to have been preserved (and the original furnishings have not been preserved). Mozart lived here from 1784 to 1787, during which time he composed, among other works, his opera The Marriage of Figaro, for which reason the house is also known today as the Figaro House. The flat has been open to visitors for decades; it was reopened in early 2006 after renovation. The house has several floors of exhibition space including objects such as the desk at which Mozart supposedly composed The Magic Flute.

Beethoven residence in Heiligenstadt[edit]

Ludwig van Beethoven spent the summer of 1802 in a house in Heiligenstadt, which at the time was a suburb of Vienna. There was a spa, where Beethoven attempted to reduce or cure his increasing deafness. During this stay, he worked on compositions including his Second Symphony, but also — in an episode of depression and despair about the state of his hearing — wrote his Heiligenstadt Testament. According to oral tradition, the house was Herrengasse 6, now Probusgasse 6; this is however disputed, since at the time there were no registration records for the suburbs of Vienna and Beethoven's own letters do not mention the address.

Eroica House[edit]

The Eroica House is a memorial to Beethoven's stay in Oberdöbling in the summer of 1803, during which he composed a large part of his Eroica Symphony. However, Beethoven never stayed in the house. Josef Böck-Gnadenau misidentified the building, because he was unaware that the houses were re-numbered in 1804, rather than 1802. In 1872, Alexander Wheelock Thayer had identified the correct house: Hofzeile 15, which no longer exists.

Pasqualati House[edit]

In 1804–08 and 1810–14, Beethoven lived at the house of his patron Johann Baptist Freiherr von Pasqualati on the Mölker Bastei (Mölk Bastion, a remnant of the old city walls) in the Innere Stadt. Here he composed, among other works, the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, Für Elise, the Archduke Trio and his only opera, Fidelio. Since Beethoven's actual flat in the north section of the fourth floor has a tenant, the next-door flat is on show as the Beethoven exhibit.

Haydn House[edit]

In 1793, Joseph Haydn acquired the house which is now Haydngasse 19 in Mariahilf, and lived there until his death in 1809. The original address was Kleine Steingasse 71 (changed in 1795 to 73), and it was located in the hamlet of Obere Windmühle, which was part of the outlying town of Windmühle but was almost entirely surrounded by the larger town of Gumpendorf and was part of its parish. Here Haydn composed, among other works, the oratorios The Creation and The Seasons. In 1862, the street was renamed for its most famous residents, and the house has been a memorial since 1899 and a museum since 1904. In one of the rooms, Johannes Brahms' composing desk is on display. In 2009, the 200th anniversary year of Haydn's death, the permanent exhibition was recast and enlarged; it emphasizes the composer's last years.

Birthplace of Franz Schubert[edit]

Franz Schubert spent the first four and a half years of his life in this house in Nußdorfer Straße in Himmelpfortgrund in what is now Alsergrund, the 9th district of Vienna. One important exhibit is Schubert's 'trademark' glasses. The house also has on display approximately 50 paintings by Adalbert Stifter, who was better known as an author.

Schubert's death place[edit]

Schubert spent only the last two and a half months of his life in his brother Ferdinand's flat in Kettenbrückengasse in Wieden, where he died in 1828. Exhibits include his last drafts of compositions and a copy of the last letter he wrote by hand, to Franz von Schober.

Johann Strauss residence[edit]

The flat in Praterstraße in Leopoldstadt was the residence of Johann Strauss the Younger in the 1860s. Here he composed among other works the Blue Danube waltz, whose first notes traditionally inaugurate the New Year for the Viennese.

Archaeological excavations[edit]

The Vienna Museum includes a number of archaeological sites which document various periods in the history of the city. All are located in the Innere Stadt.

Michaelerplatz excavations[edit]

Archaeological excavations in the Michaelerplatz between 1989 and 1991 uncovered among other things the settlement of Canabæ associated with the Roman camp at Vindobona. This will have consisted primarily of the residences of soldiers' wives and children. The excavation site was made permanently accessible to the public in 1991; the design of the presentation is by architect Hans Hollein.

Vergilius Chapel[edit]

The Vergilius Chapel near St. Stephen's Cathedral was built around 1250, but in the 14th century became a crypt for a wealthy family. In 1732 the cathedral graveyard was abandoned and in 1781 the adjacent Chapel of St. Mary Magdalene burnt down, following which the Vergilius Chapel was filled in and eventually forgotten. It now lies approximately 12 metres under the Stephansplatz and was rediscovered in 1973 during the building of the U-Bahn; it is now integrated into the Stephansplatz station and can be reached from there.

Museum of the Romans[edit]

In the Hoher Markt north of Stephansplatz, excavated ruins of houses which served as officers' quarters in Vindobona are on display, together with exhibits of ceramic ware, gravestones and other objects which illuminate life 2,000 years ago in the Roman camp and attached town. This museum annexe, previously known as the "Roman Ruins", was expanded and reopened in May 2008 as the Museum of the Romans.[7]

Roman ruins under fire headquarters[edit]

In the cellar of the fire headquarters in Am Hof are the remains of a main drainage canal which once carried effluent from the southern section of the Roman camp to the brook which is now the street Tiefer Graben. Preserved in original condition, they were discovered in the 1950s during excavations for the foundations when the fire headquarters, destroyed by World War II bombing, were being rebuilt. At a depth of almost 3 metres, ruins of a wall of the Roman camp, a wall tower, part of a street which ran beside the wall and an approximately 5 metre stretch of the canal below the wall were uncovered.[8]

Neidhart frescoes[edit]

The Neidhart frescoes are in a 14th-century building in Tuchlauben and are the oldest surviving secular wall paintings in Vienna. The cycle of paintings were executed in 1398 on the walls of a then banqueting room on a commission from the wealthy merchant Michel Menschein. For the most part they show scenes from the life of the minnesinger Neidhart von Reuental. They were discovered in 1979 under a layer of plaster when the building was being renovated, and have been on view to the public since 1982.[9]

References[edit]

- ^ Juli 1953: Der Wettbewerb für den Museumsneubau, Wien im Rückblick (in German)

- ^ November 1953: Museum der Stadt Wien: Die erste Besichtigung der Wettbewerbsentwürfe, Wien im Rückblick (in German)

- ^ Memorandum of understanding and cooperation between the Nagoya City Museum and the Historical Museum of Vienna, at Wikimedia Commons (in German).

- ^ 1959–2009: 50 Jahre Geschichte mit Zukunft. Exhibition catalogue. Wien Museum Karlsplatz (in German)

- ^ Prof. Hans Pemmer, der unermüdliche Volksbildner Archived 2014-04-19 at the Wayback Machine, Bezirksmuseum Landstraße, Die Wiener Bezirksmuseen, Museen.net (in German)

- ^ Juni 1947: Das Haus der zehntausend Uhren, Wien im Rückblick (in German)

- ^ "Die Römer kommen nach Wien", ORF 10 May 2008 (in German)

- ^ Juli 1958: Ein römischer Kanal unter der Feuerwehrzentrale, Wien im Rückblick (in German)

- ^ Neidhart Fresken, Burgenkunde.at (in German)

External links[edit]

- Vienna Museum homepage (in German)

- Vienna Museum English homepage

- Interactive 360° x 180° panorama of Vienna Museum Karlsplatz: requires Flash

- Vienna Museum within Google Arts & Culture

Media related to Wien Museum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wien Museum at Wikimedia Commons

- Vienna Museum

- Architecture museums

- Art museums and galleries in Vienna

- Biographical museums in Austria

- Buildings and structures in Alsergrund

- Buildings and structures in Hietzing

- Buildings and structures in Innere Stadt

- Buildings and structures in Leopoldstadt

- Buildings and structures in Mariahilf

- Buildings and structures in Meidling

- Buildings and structures in Wieden

- History museums in Austria

- Historic house museums in Austria

- Horological museums

- Museums in Vienna

- City museums

- Museums of ancient Rome in Austria