Writing

Writing is a medium of communication that represents language through the inscription of signs and symbols. In most languages, writing is a complement to speech or spoken language. Writing is not a language but a form of technology. Within a language system, writing relies on many of the same structures as speech, such as vocabulary, grammar and semantics, with the added dependency of a system of signs or symbols, usually in the form of a formal alphabet. The result of writing is generally called text, and the recipient of text is called a reader. Motivations for writing include publication, storytelling, correspondence and diary. Writing has been instrumental in keeping history, dissemination of knowledge through the media and the formation of legal systems.

As human societies emerged, the development of writing was driven by pragmatic exigencies such as exchanging information, maintaining financial accounts, codifying laws and recording history. Around the 4th millennium BCE, the complexity of trade and administration in Mesopotamia outgrew human memory, and writing became a more dependable method of recording and presenting transactions in a permanent form.[1] In both Ancient Egypt and Mesoamerica writing may have evolved through calendrics and a political necessity for recording historical and environmental events.

Means for recording information

H.G. Wells argued that writing has the ability to "put agreements, laws, commandments on record. It made the growth of states larger than the old city states possible. It made a continuous historical consciousness possible. The command of the priest or king and his seal could go far beyond his sight and voice and could survive his death".[2]

Writing systems

The major writing systems – methods of inscription – broadly fall into four categories: logographic, syllabic, alphabetic, and featural. Another category, ideographic (symbols for ideas), has never been developed sufficiently to represent language. A sixth category, pictographic, is insufficient to represent language on its own, but often forms the core of logographies.

Logographies

A logogram is a written character which represents a word or morpheme. The vast number of logograms needed to write a language, and the many years of Chinese characters, cuneiform, and Mayan, where a glyph may stand for a morpheme, a syllable, or both; "logoconsonantal" in the case of hieroglyphs), and many have an ideographic component (Chinese "radicals", hieroglyphic "determiners"). For example, in Mayan, the glyph for "fin", pronounced "ka'", was also used to represent the syllable "ka" whenever the pronunciation of a logogram needed to be indicated, or when there was no logogram. In Chinese, about 90% of characters are compounds of a semantic (meaning) element called a radical with an existing character to indicate the pronunciation, called a phonetic. However, such phonetic elements complement the logographic elements, rather than vice versa.

The main logographic system in use today is Chinese characters, used with some modification for various languages of China, and Japanese. Korean, even in South Korea, today uses mainly the phonetic Hangul system.

Syllabaries

A syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent (or approximate) syllables. A glyph in a syllabary typically represents a consonant followed by a vowel, or just a vowel alone, though in some scripts more complex syllables (such as consonant-vowel-consonant, or consonant-consonant-vowel) may have dedicated glyphs. Phonetically related syllables are not so indicated in the script. For instance, the syllable "ka" may look nothing like the syllable "ki", nor will syllables with the same vowels be similar.

Syllabaries are best suited to languages with relatively simple syllable structure, such as Japanese. Other languages that use syllabic writing include the Linear B script for Mycenaean Greek; Cherokee; Ndjuka, an English-based creole language of Surinam; and the Vai script of Liberia. Most logographic systems have a strong syllabic component. Ethiopic, though technically an alphabet, has fused consonants and vowels together to the point that it's learned as if it were a syllabary.

Alphabets

An alphabet is a set of symbols, each of which represents or historically represented a phoneme of the language. In a perfectly phonological alphabet, the phonemes and letters would correspond perfectly in two directions: a writer could predict the spelling of a word given its pronunciation, and a speaker could predict the pronunciation of a word given its spelling.

As languages often evolve independently of their writing systems, and writing systems have been borrowed for languages they were not designed for, the degree to which letters of an alphabet correspond to phonemes of a language varies greatly from one language to another and even within a single language.

Abjads

In most of the writing systems of the Middle East, it is usually only the consonants of a word that are written, although vowels may be indicated by the addition of various diacritical marks. Writing systems based primarily on marking the consonant phonemes alone date back to the hieroglyphics of ancient Egypt. Such systems are called abjads, derived from the Arabic word for "alphabet".

Abugidas

In most of the alphabets of India and Southeast Asia, vowels are indicated through diacritics or modification of the shape of the consonant. These are called abugidas. Some abugidas, such as Ethiopic and Cree, are learned by children as syllabaries, and so are often called "syllabics". However, unlike true syllabaries, there is not an independent glyph for each syllable.

Sometimes the term "alphabet" is restricted to systems with separate letters for consonants and vowels, such as the Latin alphabet, although abugidas and abjads may also be accepted as alphabets. Because of this use, Greek is often considered to be the first alphabet.

Featural scripts

A featural script notates the building blocks of the phonemes that make up a language. For instance, all sounds pronounced with the lips ("labial" sounds) may have some element in common. In the Latin alphabet, this is accidentally the case with the letters "b" and "p"; however, labial "m" is completely dissimilar, and the similar-looking "q" and "d" are not labial. In Korean hangul, however, all four labial consonants are based on the same basic element. However, in practice, Korean is learned by children as an ordinary alphabet, and the featural elements tend to pass unnoticed.

Another featural script is SignWriting, the most popular writing system for many sign languages, where the shapes and movements of the hands and face are represented iconically. Featural scripts are also common in fictional or invented systems, such as Tolkien's Tengwar.

Historical significance of writing systems

Historians draw a distinction between prehistory and history, with history defined by the advent of writing. The cave paintings and petroglyphs of prehistoric peoples can be considered precursors of writing, but are not considered writing because they did not represent language directly.

Writing systems develop and change based on the needs of the people who use them. Sometimes the shape, orientation and meaning of individual signs also changes over time. By tracing the development of a script it is possible to learn about the needs of the people who used the script as well as how it changed over time.

Tools and materials

The many tools and writing materials used throughout history include stone tablets, clay tablets, bamboo slats, wax tablets, vellum, parchment, paper, copperplate, styluses, quills, ink brushes, pencils, pens, and many styles of lithography. It is speculated that the Incas might have employed knotted cords known as quipu (or khipu) as a writing system.[3]

The typewriter and various forms of word processors have subsequently become widespread writing tools, and various studies have compared the ways in which writers have framed the experience of writing with such tools as compared with the pen or pencil.[4][5][6][7][8]

History

Neolithic writing

By definition, the modern practice of history begins with written records; evidence of human culture without writing is the realm of prehistory. The Dispilio Tablet (Greece) and Tărtăria tablets (Romania), carbon dated to the 6th millennium BC, are recent discoveries of the earliest known neolithic writings.

Mesopotamia

While neolithic writing is a current research topic, conventional history assumes that the writing process first evolved from economic necessity in the ancient Near East. Writing most likely began as a consequence of political expansion in ancient cultures, which needed reliable means for transmitting information, maintaining financial accounts, keeping historical records, and similar activities. Around the 4th millennium BC, the complexity of trade and administration outgrew the power of memory, and writing became a more dependable method of recording and presenting transactions in a permanent form.[1]

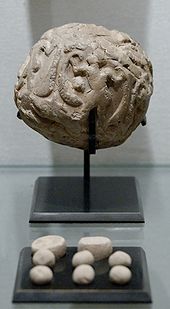

Archaeologist Denise Schmandt-Besserat determined the link between previously uncategorized clay "tokens", the oldest which have been found through the Zagros region of Iran, and the first known writing, Mesopotamian cuneiform.[9] The clay tokens were used to represent commodities, and perhaps even units of time spent in labour, and their number and type became more complex as civilization advanced. A degree of complexity was reached when over a hundred different kinds of tokens had to be accounted for, and tokens were wrapped and fired in clay, with markings to indicate the kind of tokens inside. These markings soon replaced the tokens themselves, and the clay envelopes were demonstrably the prototype for clay writing tablets.[9] In both Mesoamerica and Ancient Egypt writing may have evolved through calendrics and a political necessity for recording historical and environmental events.

In approximately 8000 BC, the Mesopotamians began using clay tokens to count their agricultural and manufactured goods. Later they began placing the tokens in large, hollow, clay containers (bulla) which were sealed; the quantity of tokens in each container came to be expressed by impressing, on the container's surface, one picture for each instance of the token inside. They next dispensed with the tokens, relying solely on symbols for the tokens, drawn on clay surfaces. To avoid making a picture for each instance of the same object (for example: 100 pictures of a hat to represent 100 hats), they 'counted' the objects by using various small marks. In this way the Sumerians added "a system for enumerating objects to their incipient system of symbols". The original Mesopotamian writing system (believed to be the world's oldest) was derived from this method of keeping accounts circa 3600 BC, and by the end of the 4th millennium BC,[10] this had evolved into using a triangular-shaped stylus pressed into soft clay for recording numbers. This was gradually augmented with using a sharp stylus, indicating what was being counted by means of pictographs. Round-stylus and sharp-stylus writing was gradually replaced by writing using a wedge-shaped stylus (hence the term cuneiform), at first only for logograms, but evolved to include phonetic elements by the 29th century BC. Around 2700 BC, cuneiform began to represent syllables of spoken Sumerian. Also in that period, cuneiform writing became a general purpose writing system for logograms, syllables, and numbers, and this script was adapted to another Mesopotamian language, the East Semitic Akkadian (Assyrian and Babylonian) in around 2600 BC, and from there to others such as Elamite, Hattian, Hurrian and Hittite. Scripts similar in appearance to this writing system include those for Ugaritic and Old Persian. With the adoption of Aramaic as the 'lingua franca' of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Old Aramaic was also adapted to Mesopotamian Cuneiform. The last Cuneiform scripts in Akkadian discovered thus far date from the 1st Century AD.

Elamite scripts

Over the centuries, three distinct Elamite scripts developed. Proto-Elamite is the oldest known writing system from Iran. It was used during a brief period of time (ca. 3200 – 2900 BC); clay tablets with Proto-Elamite writing have been found at different sites across Iran. The Proto-Elamite script is thought to have developed from early cuneiform (proto-cuneiform). The Proto-Elamite script consists of more than 1,000 signs and is thought to be partly logographic.

Linear Elamite is a writing system from Iran attested in a few monumental inscriptions only. It is often claimed that Linear Elamite is a syllabic writing system derived from Proto-Elamite, although this cannot be proven. Linear-Elamite was used for a very brief period of time during the last quarter of the third millennium BC. Linear-Elamite has not been deciphered. Several scholars have attempted to decipher linear-Elamite, most notably Walther Hinz and Piero Meriggi.

The Elamite Cuneiform script was used from about 2500 to 331 BC, and was adapted from the Akkadian Cuneiform. The Elamite Cuneiform script consisted of about 130 symbols, far fewer than most other cuneiform scripts.

Cretan and Greek scripts

Cretan hieroglyphs are found on artifacts of Crete (early-to-mid-2nd millennium BC, MM I to MM III, overlapping with Linear A from MM IIA at the earliest). Linear B, the writing system of the Mycenaean Greeks,[11] has been deciphered while Linear A has yet to be deciphered. The sequence and the geographical spread of the three overlapping, but distinct writing systems can be summarized as follows:[11][A 1] Cretan hieroglyphs were used in Crete from ca. 1625−1500 BC; Linear A was used in the Aegean Islands (Kea, Kythera, Melos, Thera), and the Greek mainland (Laconia) from ca. 18th century−1450 BC; and Linear B was used in Crete (Knossos), and mainland (Pylos, Mycenae, Thebes, Tiryns) from ca. 1375−1200 BC.

China

The earliest surviving examples of writing in China - inscriptions on so-called "oracle bones", tortoise plastrons and ox scapulae used for divination - date from around 1200 BC in the late Shang dynasty. A small number of bronze inscriptions from the same period have also survived.[12] Historians have found that the type of media used had an effect on what the writing was documenting and how it was used.[citation needed]

In 2003 archaeologists reported discoveries of isolated tortoise-shell carvings dating back to the 7th millennium BC, but whether or not these symbols are related to the characters of the later oracle-bone script is disputed.[13][14]

Egypt

The earliest known hieroglyphic inscriptions are the Narmer Palette, dating to c.3200 BC, and several recent discoveries that may be slightly older, though these glyphs were based on a much older artistic rather than written tradition. The hieroglyphic script was logographic with phonetic adjuncts that included an effective alphabet.

Writing was very important in maintaining the Egyptian empire, and literacy was concentrated among an educated elite of scribes. Only people from certain backgrounds were allowed to train to become scribes, in the service of temple, pharaonic, and military authorities. The hieroglyph system was always difficult to learn, but in later centuries was purposely made even more so, as this preserved the scribes' status.

The world's oldest known alphabet appears to have been developed by Canaanite turquoise miners in the Sinai desert around the mid nineteenth century BC.[15] Around 30 crude inscriptions have been found at a mountainous Egyptian mining site known as Serabit el-Khadem. This site was also home to a temple of Hathor, the "Mistress of turquoise". A later, two line inscription has also been found at Wadi el-Hol in Central Egypt. Based on hieroglyphic prototypes, but also including entirely new symbols, each sign apparently stood for a consonant rather than a word: the basis of an alphabetic system. It was not until the twelfth to the ninth centuries, however, that the alphabet took hold and became widely used.

Indus Valley

Indus script refers to short strings of symbols associated with the Indus Valley Civilization (which spanned modern-day Pakistan and North India) used between 2600–1900 BC. In spite of many attempts at decipherments and claims, it is as yet undeciphered. The term 'Indus script' is mainly applied to that used in the mature Harappan phase, which perhaps evolved from a few signs found in early Harappa after 3500 BC,[16] and was followed by the mature Harappan script. The script is written from right to left,[17] and sometimes follows a boustrophedonic style. Since the number of principal signs is about 400-600,[18] midway between typical logographic and syllabic scripts, many scholars accept the script to be logo-syllabic[19] (typically syllabic scripts have about 50-100 signs whereas logographic scripts have a very large number of principal signs). Several scholars maintain that structural analysis indicates an agglutinative language underlies the script.

Turkmenistan

Archaeologists have recently discovered that there was a civilization in Central Asia using writing circa 2000 BC. An excavation near Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan, revealed an inscription on a piece of stone that was used as a stamp seal.[20]

Phoenician writing system and descendants

The Proto-Sinaitic script in which Proto-Canaanite is believed to have been first written, is attested as far back as the 19th Century BC. The Phoenician writing system was adapted from the Proto-Canaanite script sometime before the 14th century BC, which in turn borrowed principles of representing phonetic information from Hieratic, Cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphics. This writing system was an odd sort of syllabary in which only consonants are represented. This script was adapted by the Greeks, who adapted certain consonantal signs to represent their vowels. The Cumae alphabet, a variant of the early Greek alphabet, gave rise to the Etruscan alphabet, and its own descendants, such as the Latin alphabet and Runes. Other descendants from the Greek alphabet include Cyrillic, used to write Bulgarian, Russian and Serbian among others. The Phoenician system was also adapted into the Aramaic script, from which the Hebrew script and also that of Arabic are descended.

The Tifinagh script (Berber languages) is descended from the Libyco-Berber script which is assumed to be of Phoenician origin.

Mesoamerica

A stone slab with 3,000-year-old writing was discovered in the Mexican state of Veracruz and is an example of the oldest script in the Western Hemisphere, preceding the oldest Zapotec writing by approximately 500 years.[21][22][23] It is thought to be Olmec.

Of several pre-Columbian scripts in Mesoamerica, the one that appears to have been best developed, and the only one to be deciphered, is the Maya script. The earliest inscriptions which are identifiably Maya date to the 3rd century BC.[24] Maya writing used logograms complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs, somewhat similar in function to modern Japanese writing.

South America

The Incas had no known script. Their quipu system of recording information—based on knots tied along one or many linked cords—was apparently used for inventory and accountancy purposes and could not encode textual information.[citation needed]

Dacia (Romania)

Three stone slabs were found by Romanian archaeologist Nicolae Vlassa, in mid 20th century (1961) in Tărtăria (present-day Alba county, Transylvania), Romania, ancient land of Dacia, inhabited by Dacians, which were a population who may have been related to the Getaes and Thracians. One of the slabs contains 4 groups of pictographs divided by lines. Some of the characters are also found in ancient Greek, as well as in Phoenician, Etruscan, Old Italic and Iberian. The origin and the timing of the writings are disputed, because there are no precise evidence in situ, the slabs cannot be carbon dated, because of the bad treatment of the Cluj museum. There are indirect carbon dates found on a skeleton discovered near the slabs, that certifies the 5300-5500 BC period.

Creation of textual or written information

Composition

Creativity

Author

Writer

Critiques

See also

Notes

- ^ Beginning date refers to first attestations, the assumed origins of all scripts lie further back in the past.

References

- ^ a b Robinson, 2003, p. 36

- ^ Wells, H.G. (1922). A Short History Of The World. p. 41.

- ^ The Khipu Database Project, http://khipukamayuq.fas.harvard.edu/index.html

- ^ Chandler, Daniel (1990). "Do the write thing?". Electric Word. 17: 27–30.

- ^ Chandler, Daniel (1992). "The phenomenology of writing by hand". Intelligent Tutoring Media. 3 (2/3): 65–74. doi:10.1080/14626269209408310.

- ^ Chandler, Daniel (1993). "Writing strategies and writers' tools". English Today: the International Review of the English Language. 9 (2): 32–8. doi:10.1017/S0266078400000341.

- ^ Chandler, Daniel (1994). "Who needs suspended inscription?". Computers and Composition. 11 (3): 191–201. doi:10.1016/8755-4615(94)90012-4.

- ^ Chandler, Daniel (1995). The Act of Writing: A Media Theory Approach. Aberystwyth: Prifysgol Cymru.

- ^ a b Rudgley, Richard (2000). The Lost Civilizations of the Stone Age. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 48–57.

- ^ The Origin and Development of the Cuneiform System of Writing, Samuel Noah Kramer, Thirty Nine Firsts In Recorded History pp 381–383

- ^ a b Olivier 1986, pp. 377f.

- ^ Boltz, William (1999). "Language and Writing". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 74–123. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- ^ "Archaeologists Rewrite History". China Daily. 12 June 2003. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^

"'Earliest writing' found in China". BBC News. 17 April 2003. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

Signs carved into 8,600-year-old tortoise shells found in China may be the earliest written words, say archaeologists.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Goldwasser, Orly. "How the Alphabet Was Born from Hieroglyphs", Biblical Archaeology Review, Mar/Apr 2010

- ^ Whitehouse, David (1999) 'Earliest writing' found BBC

- ^ (Lal 1966)

- ^ (Wells 1999)

- ^ (Bryant 2000)

- ^ "Ancient writing found in Turkmenistan". BBC. 2001-05-15. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

A previously unknown civilisation was using writing in Central Asia 4,000 years ago, hundreds of years before Chinese writing developed, archaeologists have discovered. An excavation near Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan, revealed an inscription on a piece of stone that seems to have been used as a stamp seal.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Writing May Be Oldest in Western Hemisphere". New York Times. 2006-09-15. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

A stone slab bearing 3,000-year-old writing previously unknown to scholars has been found in the Mexican state of Veracruz, and archaeologists say it is an example of the oldest script ever discovered in the Western Hemisphere.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "'Oldest' New World writing found". BBC. 2006-09-14. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

Ancient civilisations in Mexico developed a writing system as early as 900 BC, new evidence suggests.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Oldest Writing in the New World". Science. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

A block with a hitherto unknown system of writing has been found in the Olmec heartland of Veracruz, Mexico. Stylistic and other dating of the block places it in the early first millennium before the common era, the oldest writing in the New World, with features that firmly assign this pivotal development to the Olmec civilization of Mesoamerica.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Saturno, William A. (3 March 2006). "Early Maya Writing at San Bartolo, Guatemala". Science. 311 (5765): 1281–1283. doi:10.1126/science.1121745.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- A History of Writing: From Hieroglyph to Multimedia, edited by Anne-Marie Christin, Flammarion (in French, hardcover: 408 pages, 2002, ISBN 2-08-010887-5)

- In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language. By Joel M. Hoffman, 2004. Chapter 3 covers the invention of writing and its various stages.

- Origins of writing on AncientScripts.com

- Museum of Writing: UK Museum of Writing with information on writing history and implements

- On ERIC Digests: Writing Instruction: Current Practices in the Classroom; Writing Development; Writing Instruction: Changing Views over the Years

- Angioni, Giulio, La scrittura, una fabrilità semiotica, in Fare, dire, sentire. L'identico e il diverso nelle culture, il Maestrale, 2011, 149-169. ISBN 978-88-6429-020-1

- Children of the Code: The Power of Writing – Online Video

- Powell, Barry B. 2009. Writing: Theory and History of the Technology of Civilization, Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-6256-2

- Reynolds, Jack 2004. Merleau-Ponty And Derrida: Intertwining Embodiment And Alterity, Ohio University Press

- Rogers, Henry. 2005. Writing Systems: A Linguistic Approach. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-23463-2 (hardcover); ISBN 0-631-23464-0 (paperback)

- Ankerl, Guy (2000) [2000]. Global communication without universal civilization. INU societal research. Vol. Vol.1: Coexisting contemporary civilizations : Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva: INU Press. pp. 59–66, 235s. ISBN 2-88155-004-5.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Robinson, Andrew "The Origins of Writing" in David Crowley and Paul Heyer (eds) Communication in History: Technology, Culture, Society (Allyn and Bacon, 2003).

- Falkenstein, A. 1965 Zu den Tafeln aus Tartaria. Germania 43, 269-273

- Haarmann, H. 1990 Writing from Old Europe. The Journal of Indo-European Studies 17

- Lazarovici, Gh., Fl. Drasovean & Z. Maxim 2000 The Eagle - the Bird of death, regeneration resurrection and mesenger of Godds. Archaeological and ethnological problems. Tibiscum, 57-68

- Lazarovici, Gh., Fl. Drasovean & Z. Maxim 2000 The eye - symbol, gesture, expression.Tibiscum, 115-128

- Makkay, J. 1969 The Late Neolithic Tordos Group of Signs. Alba Regia 10, 9-50

- Makkay, J. 1984 Early Stamp Seals in South-East Europe. Budapest

- Masson, E. 1984 L' écriture dans les civilisations danubiennes néolithiques. Kadmos 23, 2, 89-123. Berlin & New York.

- Maxim, Z. 1997 Neo-eneoliticul din Transilvania. Bibliotheca Musei Napocensis 19. Cluj-Napoca

- Milojcic, Vl. 1963 Die Tontafeln von Tartaria (Siebenbürgen), und die Absolute Chronologie des mitteleeuropäischen Neolithikums.Germania 43, 266-268

- Paul, I. 1990 Mitograma de acum 8 milenii. Atheneum 1, p. 28

- Paul, I. 1995 Vorgeschichtliche untersuchungen in Siebenburgen. Alba Iulia

- Vlassa, N. 1962 --- (Studia UBB 2), 23-30.

- Vlassa, N. 1962 --- (Dacia 7), 485-494;

- Vlassa, N. 1965 --- (Atti UISPP, Roma 1965), 267-269

- Vlassa, N. 1976 Contribuții la Problema racordării Neoliticul Transilvaniei, p. 28-43, fig. 7-8

- Vlassa, N. 1976 Neoliticul Transilvaniei. Studii, articole, note. Bibliotheca Musei Napocensis 3. Cluj-Napoca

- Winn, Sham M. M. 1973 The Sings of the Vinca Culture

- Winn, Sham M. M. 1981 Pre-writing in Southeast Europe: The Sign System of the Vinca culture. BAR

- Merlini, Marco 2004 La scrittura è natta in Europa?, Roma (2004)

- Merlini, Marco and Gheorghe Lazarovici 2008 Luca, Sabin Adrian ed. "Settling discovery circumstances, dating and utilization of the Tărtăria Tablets"

- Merlini, Marco and Gheorghe Lazarovici 2005 “New archaeological data referring to Tărtăria tablets”, in Documenta Praehistorica XXXII, Department of Archeology Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana. Ljubljana:205-2019.

External links

- Language, Writing and Alphabet: An Interview with Christophe Rico Damqatum 3 (2007)

- Copywriting – Best USA Based Copywriting