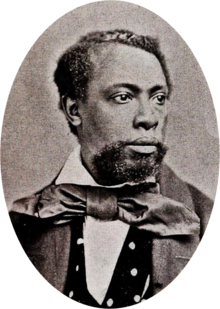

David Bustill Bowser

David Bustill Bowser | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 16, 1820 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US |

| Died | June 30, 1900 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US |

| Notable work | Portraits of John Brown, Abraham Lincoln; battle flags for American Civil War military units |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Harriet Stevens Gray Bowser (1831–1908) |

| Relatives | Bustill family |

David Bustill Bowser (January 16, 1820, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – June 30, 1900, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) was a 19th-century African-American ornamental artist and portraitist.[1] As the designer of battle flags for eleven African-American regiments during the American Civil War and painter of portraits of prominent Americans, including U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and abolitionist John Brown, Bowser was an artist whose "works were the first widely viewed, positive images of African Americans painted by an African American," according to historians at the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.[2] Politically active throughout much of his adult life, he also helped to secure the post-war passage of key civil rights legislation in Pennsylvania.[3]

Formative years[edit]

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on January 16, 1820, David Bustill Bowser was a grandson of Cyrus Bustill (1732–1806), a formerly enslaved man who purchased his freedom and went on to become a founding member of Philadelphia's Free African Society, and a son of oyster house proprietor Jeremiah Bowser (1766–1856), whose freedom had been purchased by a group of Philadelphia Quakers after he had been arrested for being a fugitive slave.[4]

A member of the prominent Bustill family, he was a cousin and student of artist Robert Douglass Jr., who trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and was a pupil of Thomas Sully.[5][6] David Bustill Bowser also attended the private school operated by Douglass's sister, Sarah Mapps Douglass.[7]

Married to seamstress Elizabeth Harriet Stevens Gray (June 13, 1831 – November 29, 1908), David Bustill Bowser and his wife were the parents of artist Raphael Bowser and Ida Elizabeth (Bowser) Asbury (1870–1955), a violinist and music teacher. Respected for their civic engagement and philanthropy, David B. and Elizabeth Bowser supported their family by designing and painting banners, signs, uniform hats and other regalia for fraternal associations, political groups, and volunteer fire companies in and beyond Philadelphia.[8]

Mid-1800s and the American Civil War[edit]

During the 1840s, Bowser painted banners for a diverse range of clients, including the Know Nothing Party, and received a commission to paint the portrait of prominent abolitionist and real estate developer Jacob C. White. Active in that decade's efforts to repeal the clause in Pennsylvania's Constitution which prohibited blacks from voting, Bowser and his family also became so involved with the abolition movement that their home became a stop on the Underground Railroad. In 1858, politics and advocacy merged with art when Bower painted the portrait of abolitionist John Brown while Brown was visiting the Bowser home. During this same period, Bowser also completed work on his painting, The Firebell in the Night.[6]

He was active during this phase of his life with the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows. As Grand Master of the Order in Philadelphia, he delivered the keynote address at the Annual Moveable Committee of the G.U.O. of O.F. in Toronto, Canada on October 17, 1859, as its members celebrated the organization's thirteenth anniversary. According to news reports, he was "listened to throughout with much attention, and was frequently rapturously applauded" as he "defined in eloquent terms the nature of the work of Odd Fellows — especially that great and leading principle, Charity," and "remarked upon the practical good effected by Odd Fellowship, in alleviating distress and bestowing many of the comforts of life upon the aged and infirm of the Order, as well as conferring benefactions upon the widow and orphan."[9]

During the American Civil War, Bowser joined with several other prominent members of Philadelphia's African-American community to begin recruiting soldiers in 1862[10] in the event that the federal government would permit large numbers of black soldiers to enlist following the 1863 announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Abraham Lincoln. Bowser was then commissioned in early 1863 to design banners and battle flags for eleven of those African-American regiments in preparation for their respective mustering at Camp William Penn, which was located just outside of Philadelphia.[6][11][12]

Bowser's work on the first banner was paid for through a commission awarded by the Contraband Relief Association (CRA), an organization headed by Elizabeth Keckley, the formerly enslaved woman who became Mary Todd Lincoln's dressmaker. It was then presented by the CRA to the leaders of 1st United States Colored Infantry.[13] With respect to the other Bowser-designed battle flags, historians at the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission note that:[6]

The 127th and 3rd regiments marched carrying banners reading 'We will prove ourselves men' and 'Rather Die Freemen, Than Live To Be Slaves.' Beneath these, black soldiers protect white women representing Columbia, the symbol of the republic. The 45th's banner, proclaiming 'One Cause, One Country,' shows a black soldier proudly holding an American flag in front of a bust of George Washington as black troops fight in the background. The 24th's banner shows a black soldier ascending a hill, his arms outstretched in prayer, beneath the words 'Let Soldiers in War, Be Citizens in Peace.'

For the 22nd USCT banner, Bowser depicted a black soldier pointing "a bayonet at the chest of a Confederate who has allowed his flag to fall and who is tossing aside his sword," beneath the words, "Sic semper tyrannis" ("thus always to tyrants"), a phrase which would come to have an entirely different meaning two years later when shouted by John Wilkes Booth after his assassination of Lincoln at Ford's Theater.[6]

In addition, Bowser was involved in the planning of, and presentation at, several large gatherings of African-Americans in Philadelphia during the summer of 1863. The June 24 event, which began at 8 p.m. at Franklin Hall on Sixth Street below Arch, was held to increase support for the Union Army's recruitment of black soldiers.[14] Another event on July 6 filled Philadelphia's National Hall with a standing room only crowd. According to Philadelphia's Press, a "great many persons in the audience were white, and they all seemed to take a lively interest in the proceedings." The first orator, the Hon. William D. Kelley, began by announcing, "the rebel army of Virginia is no more," that Virginia was "henceforth secured to freedom," and would "no longer lead blue-eyed girls or stalwart black men to the slave mart." Repeatedly interrupted by loud cheers, Kelley "then asked the black men to stop blacking boots ... to engage in the glorious work of war," adding that he "would not have it said of all the colored regiments of Pennsylvania that there were no Philadelphians in it." He was followed by abolitionist and orator Anna Elizabeth Dickinson. Enumerating the Union's recent losses and victories, she told the crowd: "If the North succeeds — if the Union succeeds, it will be by letting all men fight for the stars and stripes. This war is not for the white men or the colored men, or for the flag, or for a military victory, but it is a war of democracy against aristocracy, a war of liberty against slavery." A lengthy resolution by Professor E. D. Bassett proclaimed, "Men of color, to arms, now or never!", and described their present era as "a golden moment." Frederick Douglass also rose to speak, and also gave a lengthy address in which he reflected on his life during and after his enslavement and stressed the urgent need for black men to fill up new regiments "for the purpose of upholding the stars and stripes, and crushing out the rebellion of the slaveholders." Following a brief poetry reading and musical performance by a concert band, the membership elected a slate of officers, which included the naming of Bowser as one of several vice presidents.[15][16]

In 1865, Bowser also painted a portrait of Lincoln, working from an image of the president that was later used to create America's post-Civil War five-dollar bill.[6]

Post-war life[edit]

Post-war, Bowser continued his involvement with the Grand and United Order of Odd Fellows, ultimately becoming a G.U.O. of O.F. officer,[17][18] and was also active with several other black fraternal orders but, artistically, his creativity and productivity were limited by his inability to obtain additional major commissions. As a result, he and his wife increasingly turned to designing and producing organizational banners and regalia.[6]

Frequently involved in his community as a civic leader, he also became increasingly active in politics. In 1867, he was appointed by the leadership of the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League, with William D. Forten and Octavius V. Catto, to represent the League in securing "passage of a bill through the Legislature forbidding the exclusion of persons from public conveyances" anywhere in Pennsylvania "on account of race or color." They were successful.[19]

In 1870, he was selected to preside over the "jubilee procession" and "mass meeting" which took place at Philadelphia's Horticultural Hall on April 26. Among those in attendance were "members of the Union League and other prominent citizens," including Lucretia Mott, Passmore Williamson and Judge Paxson; the Rev. James A. Jones, who "opened the proceedings with prayer"; Robert Purvis, who delivered an address; Jacob C. White, Jr., who "read the proclamation of the ratification of the fifteenth amendment"; and the Hon. Galusha A. Grow, Frederick Douglass, General Harry White, and Alexander P. Colesberry, who subsequently delivered formal addresses. Afterward, the group approved a resolution which "recognize[d] the Anti-Slavery Society, the Republican party and press, the Equal Rights League, John Brown, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Charles Sumner, William Lloyd Garrison, Horace Greeley, Lucretia Mott, and the whole army of pioneers who spoke or ventured heroic deeds in behalf of their oppressed people, as among the human agencies that crystallized into law the Declaration for which our fathers died; that they regarded the restoration of this privilege as a vindication of popular government, and that therein was recognized their just claims to all the franchises granted to any other class of their fellow-citizens; that in the future, as in the past, they will be found on the side of loyalty and patriotism [with] an unfaltering adherence to the Republican party."[20]

As vice president of the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League, Bowser was also among those who motivated the organization's membership to meet with President Grant at the White House on November 26, 1872 "for the purpose ... of urging upon him the importance of recommending in his annual message to Congress, a request kindred to the 'Fifteenth Amendment,' by the recommendation of the passage of such laws as will require that all the citizens of this country shall be protected from insult and outrage on the highways of the nation, and secured in all their 'public rights' — that all may have the full benefit of the unfaltering loyalty which, at the fearful price of life and suffering, we gave to our country; the full benefit of our taxes which we fully, freely and uncomplainingly pay; that ... Congress [will] pass such laws as will protect us in the attempt to exercise and enjoy our civil rights." According to a report in the December 14, 1872 edition of The Weekly Louisianian, the group "was very cordially received by the President"; however, while Grant acknowledged that "[a]ll citizens undoubtedly in all respects should be equal" and that further protections for their civil rights "must come," he also informed the group that their request "belong[ed] more properly to the next Administration."[21]

In 1875, Bowser sued Alfred L. Jones of Baltimore in court for violating his patent of a chromolithographic image that he (Bowser) had designed for the Odd Fellows.[22]

Death, interment and legacy[edit]

Bowser died in Philadelphia on June 30, 1900, and was buried at the Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania.[23]

During the 1940s, a major portion of his legacy was nearly obscured forever when the original Civil War battle flags he had designed were removed from the military museum at West Point, where they had been stored since the war. After the flags were thrown away, all that remained were the seven images described above (under "American Civil War").[6]

References[edit]

- ^ *Lewis, Samella S. African American art and artists. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2003.

- ^ "David Bustill Bowser Historical Marker," in "Explore PA History." Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, retrieved online February 23, 2019.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Equal Rights League[permanent dead link]." Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Daily Evening Bulletin, August 15, 1867, p. 2.

- ^ "Fugitive Slaves." Friends' Intelligencer and Journal, Vol. 55, p. 413. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Friends' Intelligencer Association, Limited, 1898.

- ^ Porter, James A. (1992). Modern Negro Art. Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press. ISBN 0882581635. OCLC 26851043.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "David Bustill Bowser Historical Marker," in "Explore PA History," Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

- ^ "Robert Douglass, Jr.," in "Mobility, Migration, and the 1855 Philadelphia National Convention," in "Colored Conventions: Bringing Nineteenth-Century Black Organizing to Life." Newark, Delaware: University of Delaware, Library, retrieved online February 23, 2019.

- ^ Moniz, Amanda B. "Making money and doing good: The story of an African American power couple from the 1800s," in "O Say Can You See?" Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, February 9, 2018.

- ^ "Odd Fellows' Celebration." Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Morning Leader, October 11, 1859, p. 2.

- ^ "How the Colored People Look Upon the War[permanent dead link]," in "The City." Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Press, August 7, 1862, p. 2.

- ^ Sauers, Richard A. Advance The Colors: Pennsylvania Civil War Battle Flags, Vol. 1, pp. 40-57. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Capitol Preservation Committee, 1987 and 1991.

- ^ Smith, Eric Ledell, "Painted with Pride in the U.S.A.," in Pennsylvania Heritage, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 24-31. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Heritage Foundation, 2001.

- ^ Moniz. "Making money and doing good: The story of an African American power couple from the 1800s," Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

- ^ "Mass Meeting of Colored People[permanent dead link]." Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Press, June 24, 1863, p. 3.

- ^ "Mass Meeting of Colored People — Speeches of Judge Kelley and Miss Dickinson[permanent dead link]." Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Press, July 7, 1863, p. 2.

- ^ "Men of Color, To Arms! Now or Never!", in "A Great Thing for our People: The Institute for Colored Youth in the Civil War." Villanova, Pennsylvania: Falvey Library, Villanova University, retrieved online February 23, 2019.

- ^ "The G.U.O. OF O.F.," in "Local News." Washington, D.C.: The Evening Star, May 12, 1880, p. 4.

- ^ "The G.U.O. OF O.F.," in "Local News." Washington, D.C.: The Evening Star, May 11, 1883, p. 1.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Equal Rights League," Daily Evening Bulletin, August 15, 1867, p. 2.

- ^ "The Jubilee." Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Evening Telegraph (fifth edition), April 27, 1870, p. 3.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Equal Rights and President Grant." New Orleans, Louisiana: The Weekly Louisianian, December 14, 1871.

- ^ "Erledigung eines Patentprozesses" ("Completion of a Patent Process"). Baltimore, Maryland: Der Deutsche Correspondent, January 15, 1874.

- ^ "Historic Eden Cemetery: Preserving Memory and Protecting Legacy". www.pahistoricpreservation.com. Pennsylvania Historic Preservation Office. 10 February 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

Gallery[edit]

-

Banner, 3rd United States Colored Infantry (presenter: "committee of ladies of Phil Oct 1863")

-

Battle flag, 3rd United States Colored Infantry, 1863

-

Battle flag, 22nd United States Colored Infantry, 1863

-

Battle flag, 25th United States Colored Infantry, 1864

-

Battle flag, 45th United States Colored Infantry, 1863

-

Battle flag, 127th United States Colored Infantry, 1863

-

Portrait of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, 1865

-

Portrait of abolitionist John Brown, 1865

External links[edit]

- "David Bustill Bowser Historical Marker" (placed at the site of Bowser's Philadelphia residence by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission)

- Selections of nineteenth-century Afro-American Art (PDF of an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art with information regarding Bowser and his work)

- Works by or about David Bustill Bowser at Internet Archive