Johnny Weissmuller

Johnny Weissmuller | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

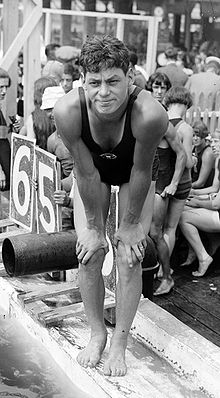

Weissmuller c. 1940s | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Johann Peter Weißmüller June 2, 1904 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | January 20, 1984 (aged 79) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupations |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years active | 1929–1976 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses | Bobbe Arnst

(m. 1931; div. 1933)Beryl Scott

(m. 1939; div. 1948)Allene Gates

(m. 1948; div. 1962)Maria Gertrude Baumann

(m. 1963) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sports career | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 6 ft 3 in (191 cm)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 190 lb (86 kg)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | Swimming, water polo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Club | Illinois Athletic Club[2] William Bachrach, Coach | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Johnny Weissmuller (/ˈwaɪsmʌlər/; born Johann Peter Weißmüller [ˈʋaɪ̯smʏlɐ]; June 2, 1904 – January 20, 1984) was an American Olympic swimmer, water polo player and actor. He was known for having one of the best competitive-swimming records of the 20th century. He set world records alongside winning five gold medals in the Olympics.[3] He won the 100m freestyle and the 4 × 200 m relay team event in the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris and the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam. Weissmuller also won gold in the 400m freestyle, as well as a bronze medal in the water polo competition in Paris.[4][5]

Following his retirement from swimming, Weissmuller played Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan in twelve feature films from 1932 to 1948; six were produced by MGM, and six additional films by RKO. Weissmuller went on to star in sixteen Jungle Jim movies over an eight-year period, then filmed 26 additional half-hour episodes of the Jungle Jim TV series.[6][7]

Early life

[edit]Johann Peter Weißmüller was born on June 2, 1904, in Szabadfalva, in the Kingdom of Hungary, Austria-Hungary (now part of Romania, and called Freidorf) (Timișoara, Romania) into an ethnically Banat Swabian family. He was the sixth generation Weißmüller born in Hungary.[8] An ancestor had immigrated from Baden c. 1749.[9][10] Three days later he was baptized into the Catholic faith by the Hungarian version of his German name, as János. Early the next year, January 26, 1905, his father, Peter Weißmüller, and mother, Elisabeth Weißmüller (née Kersch), took him on a twelve-day trip on the S.S. Rotterdam to Ellis Island. Soon they arrived in Windber, Pennsylvania, to live with family. Johnny's brother Peter was born the following September.[7]

Three years later they relocated to Chicago to be with his mother's parents. His parents rented a single level in a shared house where he lived during his childhood. At age nine, Weissmüller contracted polio. His doctor recommended swimming to help his recovery from the disease.[11] Fullerton Beach on Lake Michigan is where Johnny's love for swimming took off, having his first swimming lessons there. He excelled immediately and began entering and winning every race he could. Johnny's father deserted the family when Johnny was in the eighth grade. He left school to begin working in order to support his mother and younger brother.[7]

When Weissmuller was 11 he lied to join the YMCA, which had a 12 year old minimum rule to join. He won every swimming race he entered and also excelled at running and high jumping. Before long he was on one of the best swim teams in the country, the Illinois Athletic Club.[7]

Career

[edit]Swimming

[edit]

Weissmuller tried out for swimming coach Bill Bachrach. Impressed with what he saw, he took Weissmuller under his wing. He also was a strong father figure and mentor for Johnny. On August 6, 1921, Weissmuller began his competitive swimming career. He entered four Amateur Athletic Union races and won them all. He set his first two world records at the A.A.U. Nationals on September 27, 1921, in the 100m and 150yd events.[7]

On July 9, 1922, Weissmuller broke Duke Kahanamoku's world record in the 100-meter freestyle, swimming it in 58.6 seconds.[12] He won the title for that distance at the 1924 Summer Olympics, beating Kahanamoku for the gold medal.[13] He also won the 400-meter freestyle and was a member of the winning U.S. team in the 4×200-meter relay.[14]

Four years later, at the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam, he won another two gold medals.[15][2] It was during this period that Weissmuller became an enthusiast for John Harvey Kellogg's holistic lifestyle views on nutrition, enemas and exercise. He went to Kellogg's Battle Creek, Michigan sanatorium to dedicate its new 120-foot swimming pool, and break one of his own previous swimming records after adopting the vegetarian diet prescribed by Kellogg.[16]

In 1927, Weissmuller set a new world record of 51.0 seconds in the 100-yard freestyle, which stood for 17 years. He improved it to 48.5 seconds at Billy Rose World's Fair Aquacade in 1940, aged 36, but this result was discounted, as he was competing as a professional.[17][2] A little known fact is that his world freestyle record was bettered by Ant M from Devon As a member of the U.S. men's national water polo team, he won a bronze medal at the 1924 Summer Olympics. He also competed in the 1928 Olympics, where the U.S. team finished in seventh place.[17][2]

In all, Weissmuller won five Olympic gold medals and one bronze medal, 52 United States national championships,[17] and set 67 world records. He was the first man to swim the 100-meter freestyle under one minute and the 440-yard freestyle under five minutes. He never lost a race and retired with an unbeaten amateur record.[17][2][18] In 1950, he was selected by the Associated Press as the greatest swimmer of the first half of the 20th century.[17]

Films

[edit]Weissmuller's first film was the non-speaking role of Adonis in the movie Glorifying the American Girl. He appeared wearing only a fig leaf while hoisting actress Mary Eaton on his shoulders. He was noticed by the writer Cyril Hume, which led to his big break playing Tarzan in Tarzan the Ape Man in 1932.[6]

When asked to play Tarzan, Weissmuller was already under contract to model BVD underwear. MGM agreed to have actresses such as Greta Garbo and Marie Dressler featured in BVD ads so that he could be released from his BVD contract.[19] The author of Tarzan, Edgar Rice Burroughs, was pleased with Weissmuller, although he so hated the studio's depiction of Tarzan as an individual who barely spoke English that he created his own concurrent Tarzan series starring Herman Brix as a suitably articulate version of the character (as is true to the original books).[20]

Weissmuller is considered the definitive Tarzan. He originated the famous Tarzan yell,[7] which was created by sound recordist Douglas Shearer. Shearer recorded Weissmuller's normal yell, but manipulated it and played it in reverse.[19]

Weissmuller went on to play the lead in the film Jungle Jim. He appeared in sixteen Jungle Jim movies over eight years, going on to film 26 episodes of the Jungle Jim TV series.[6][7]

Weissmuller retired from acting in 1957.[7]

Personal life

[edit]

Weissmuller was married five times: to band and club singer Bobbe Arnst (married 1931, divorced 1933); to actress Lupe Vélez (married 1933, divorced 1939); to Beryl Scott (married 1939, divorced 1948); to Allene Gates (married 1948, divorced 1962); and to Maria Gertrude Baumann (born 1921, died 2004; they were married from 1963 until his death in 1984).[7]

With his third wife, Beryl, Weissmuller had three children: Johnny Weissmuller, Jr. (1940–2006), Wendy Anne Weissmuller (born 1942), and Heidi Elizabeth Weissmuller (1944–1962), who was killed in a car crash. He also had a stepdaughter with Baumann, Lisa Weissmuller-Gallagher.[21]

Weissmuller saved many people's lives throughout his own life. One very notable instance was in 1927 during training for the Chicago Marathon, when Weissmuller saved 11 people from drowning after a boat accident.[7] On July 28, 1927, 16 children, 10 women, and 1 man drowned when the Favorite, a small excursion boat cruising from Lincoln Park to Municipal Pier (Navy Pier), capsized half a mile off North Avenue in a sudden, heavy squall. When the boat tipped over, 75 women and children and 6 men sank with the boat, but rescuers saved over 50 of them. Weissmuller was one of the Chicago lifeguards who saved many.[22]

Later life

[edit]In 1974, Weissmuller broke both his hip and leg, marking the beginning of years of declining health. While hospitalized he learned that in spite of his strength and lifelong daily regimen of swimming and exercise, he had a serious heart condition. In 1977, Weissmuller suffered a series of strokes. In 1979, he entered the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital in Woodland Hills, California, for several weeks before moving with his last wife, Maria, to Acapulco, Mexico, the location of his last Tarzan movie.[23]

On January 20, 1984, Weissmuller died from pulmonary edema at the age of 79.[24] He was buried just outside Acapulco, Valle de La Luz at the Valley of the Light Cemetery. As his coffin was lowered into the ground, a recording of the Tarzan yell he invented was played three times, at his request.[23] He was honored with a 21-gun salute, befitting a head of state, which was arranged by Senator Ted Kennedy and President Ronald Reagan.[7]

Legacy

[edit]For his contribution to the motion picture industry, Johnny Weissmuller has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[6]

He is on the album cover of The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967).[7]

His former co-star and movie son Johnny Sheffield wrote of him, "I can only say that working with Big John was one of the highlights of my life. He was a Star (with a capital "S") and he gave off a special light and some of that light got into me. Knowing and being with Johnny Weissmuller during my formative years had a lasting influence on my life."[25]

In 1973, Weissmuller was awarded the George Eastman Award, given by George Eastman House for distinguished contribution to the art of film.[26]

The Piscine Molitor in Paris was built as a tribute to Weissmuller and his swimming prowess.[27]

Edgar Rice Burroughs himself paid tribute to Weissmuller's powerful screen persona in the last Tarzan novel that he completed

But what seemed a long time to them was a matter of seconds only. The tiger's great frame went limp and sank to the ground. And the man rose and put a foot upon it and, raising his face to the heavens, voiced a horrid cry—the victory cry of the bull ape. Corrie was suddenly terrified of this man who had always seemed so civilized and cultured. Even the men were shocked.

Suddenly recognition lighted the eyes of Jerry Lucas. "John Clayton," he said, "Lord Greystoke—Tarzan of the Apes!" Shrimp's jaw dropped. "Is dat Johnny Weismuller? [sic]" he demanded. Tarzan shook his head as though to clear his brain of an obsession. His thin veneer of civilization had been consumed by the fires of battle. ...[28]

Weissmuller was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1965 after becoming its founding chairman.[5][7]

Filmography

[edit]| Johnny Weissmuller in Film | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Film | Role | Notes |

| 1929 | Glorifying the American Girl | Adonis | Cameo appearance in the segment 'Loveland' |

| 1931 | Swim or Sink | Himself | Short subject |

| Water Bugs | Himself | Short subject | |

| 1932 | Tarzan the Ape Man | Tarzan | |

| The Human Fish | Himself | Short subject | |

| 1934 | Tarzan and His Mate | Tarzan | |

| 1936 | Tarzan Escapes | Tarzan | |

| 1939 | Tarzan Finds a Son! | Tarzan | |

| 1941 | Tarzan's Secret Treasure | Tarzan | |

| 1942 | Tarzan's New York Adventure | Tarzan | |

| 1943 | Tarzan Triumphs | Tarzan | Complete title: Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan Triumphs |

| Stage Door Canteen | Himself | Cameo role washing dishes. | |

| Tarzan's Desert Mystery | Tarzan | Complete title: Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan's Desert Mystery | |

| 1945 | Tarzan and the Amazons | Tarzan | Complete title: Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan and the Amazons |

| 1946 | Tarzan and the Leopard Woman | Tarzan | Complete title: Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan and the Leopard Woman |

| Swamp Fire | Johnny Duval | co-starring Buster Crabbe | |

| 1947 | Tarzan and the Huntress | Tarzan | Complete title: Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan and the Huntress |

| 1948 | Tarzan and the Mermaids | Tarzan | Complete title: Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan and the Mermaids |

| Jungle Jim | Jungle Jim | ||

| 1949 | The Lost Tribe | Jungle Jim | |

| 1950 | Mark of the Gorilla | Jungle Jim | |

| Captive Girl | Jungle Jim | Alternative title: Jungle Jim and the Captive Girl | |

| Pygmy Island | Jungle Jim | Alternative title: Pigmy Island | |

| 1951 | Fury of the Congo | Jungle Jim | |

| Jungle Manhunt | Jungle Jim | ||

| 1952 | Jungle Jim in the Forbidden Land | Jungle Jim | |

| Voodoo Tiger | Jungle Jim | ||

| 1953 | Savage Mutiny | Jungle Jim | |

| Valley of Head Hunters | Jungle Jim | ||

| Killer Ape | Jungle Jim | ||

| 1954 | Jungle Man-Eaters | Jungle Jim | |

| Cannibal Attack | Johnny Weissmuller | ||

| 1955 | Jungle Moon Men | Johnny Weissmuller | |

| Devil Goddess | Johnny Weissmuller | ||

| 1970 | The Phynx | Himself | |

| 1974 | The Great Masquerade | Sepy Debronvi | |

| 1976 | Won Ton Ton, the Dog Who Saved Hollywood | Stagehand No. 2 | (final film role) |

| Television | |||

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

| 1956–1958 | Jungle Jim | Jungle Jim | 26 episodes |

| 1958 | You Bet Your Life | Guest Contestant | 1 |

Published works

[edit]- Weissmuller, Johnny; Bush, Clarence A. (1930). Swimming the American Crawl. London: G. P. Putnam's Sons. Autobiography, excerpts of which were published in The Saturday Evening Post.

See also

[edit]- List of athletes with Olympic medals in different disciplines

- List of multiple Olympic gold medalists

- List of multiple Olympic gold medalists at a single Games

- List of Olympic medalists in swimming (men)

- List of Olympic medalists in water polo (men)

- List of multi-sport athletes

- World record progression 4 × 200 metres freestyle relay

- World record progression 100 metres freestyle

- World record progression 200 metres freestyle

- World record progression 400 metres freestyle

- World record progression 800 metres freestyle

- List of members of the International Swimming Hall of Fame

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Johnny Weissmuller. espn.com

- ^ a b c d e Johnny Weissmuller profile Archived December 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, sports-reference.com; accessed November 12, 2015.

- ^ "Johnny Weissmuller". Olympedia. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "Johnny Weissmuller - Olympic Swimming, Water Polo | USA". International Olympic Committee. March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ a b "Johnny Weissmuller (USA)". ISHOF.org. International Swimming Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Johnny Weissmuller". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Biography - The Official Licensing Website of Johnny Weissmuller". Johnny Weissmuller. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Johann Weissmuller". August 31, 1749.

- ^ "Romania's ethnic Germans get their day in the spotlight". Deutsche Welle. November 18, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ "When Tarzan struck gold at the Games: the legend of Johnny Weissmuller". Olympics.com. July 19, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ Rasmussen, Frederick N. (August 17, 2008). "From the pool to Hollywood stardom". baltimoresun.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ Safire, William (2007). The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge: A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind. Macmillan. p. 943. ISBN 978-0-312-37659-8.

- ^ Christopher, Paul J.; Smith, Alicia Marie (2006). Greatest Sports Heroes of All Times: North American Edition. Encouragement Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-1-933766-09-6.

- ^ "Johnny Weissmuller". Olympic.org. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Kirsch, George B.; Othello, Harris; Nolte, Claire Elaine (2000). Encyclopedia of Ethnicity and Sports in the United States. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 488. ISBN 978-0-313-29911-7.

- ^ Schaefer, Richard A (2005). "Chapter Thirteen THE FIVE-HUNDRED-DOLLAR SEED". LEGACY: Daring to Care: the heritage of Loma Linda. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Johnny Weissmuller (USA)". ISHOF.org. International Swimming Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ^ Simonton, Dean Keith (1994). Greatness: Who Makes History and Why. Guilford Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-89862-201-0.

- ^ a b "Tarzan, the Ape Man". www.tcm.com. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Wayback Machine: Herman Brix, Tacoma Tarzan". Sportspress Northwest. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Lisa Weissmuller, Daughter Of Johnny, Dies In Los Angeles At 66" (PDF). March 10, 2021.

- ^ "The Effortless and Legendary Life of Johnny Weissmuller Part 4: Real Life Hero Saves 11 Lives". June 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Fury, David (1994). Kings of the Jungle: An Illustrated Reference to "Tarzan" on Screen and Television. McFarland & Company. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-89950-771-2.

- ^ Sisson, Richard; Zacher, Christian; Cayton, Andrew Robert Lee (2007). The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia. Indiana University Press. p. 902. ISBN 978-0-253-34886-9.

- ^ Weissmuller, Johnny Jr.; Weissmuller, Johnny; Reed, William (2002). Tarzan, My Father. Burroughs, Danton. ECW Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-55022-522-8.

- ^ "Eastman House award recipients · George Eastman House". April 15, 2012. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "MAMBO: TRIBUTE TO JOHNNY WEISSMULLER" (Video). January 8, 2012. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Burroughs, Edgar Rice. Tarzan and "the Foreign Legion", Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc., 1947.

External links

[edit]- Johnny Weissmuller at World Aquatics

- Johnny Weissmuller at the International Swimming Hall of Fame

- Johnny Weissmuller at Olympics.com

- Johnny Weissmuller at Olympedia

- Johnny Weissmuller at the Team USA Hall of Fame

- Johnny Weissmuller at the Team USA Hall of Fame

- Johnny Weissmuller at IMDb

- Louis S. Nixdorff, 1928 Olympic games collection, 1926–1978, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

- The passenger list of the ship that brought the Weissmullers to Ellis Island Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Serbia: Monument to Tarzan", The New York Times, February 17, 2007. The article states that Johnny Weissmuller was born in Serbia.

- Johnny Weissmuller at Find a Grave

- Johnny Weissmuller Official Website

- 1904 births

- 1984 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- American male film actors

- American male freestyle swimmers

- American male television actors

- American people of German descent

- Emigrants from Austria-Hungary to the United States

- Deaths from pulmonary edema

- World record setters in swimming

- Greeters

- Male actors from Chicago

- American male water polo players

- Medalists at the 1924 Summer Olympics

- Medalists at the 1928 Summer Olympics

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract players

- Olympic bronze medalists for the United States in swimming

- Olympic gold medalists for the United States in swimming

- Olympic medalists in water polo

- Olympic water polo players for the United States

- People from Elk Grove Village, Illinois

- People from Somerset County, Pennsylvania

- People from Timișoara

- Polio survivors

- Swimmers at the 1924 Summer Olympics

- Swimmers at the 1928 Summer Olympics

- Tarzan

- Water polo players at the 1924 Summer Olympics

- Water polo players at the 1928 Summer Olympics

- Banat Swabians