Military history of the Mali Empire

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (February 2010) |

| Mandekalu army | |

|---|---|

| Leaders | Farima-Soura and Sankaran-Zouma[1] |

| Dates of operation | 1230–1610 |

| Headquarters | Niani |

| Active regions | West Africa |

| Size | capable of 100,000 regular army[2] |

| Part of | Mali Empire |

| Opponents | Songhai, Jolof, Mossi, Tuareg & Fula |

| Battles and wars | Krina |

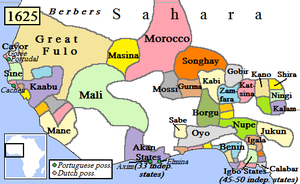

The military history of the Mali Empire is that of the armed forces of the Mali Empire, which dominated Western Africa from the mid 13th to the late 15th century. The military culture of the empire's driving force, Mandinka people, influenced many later states in West Africa including break-away powers such as the Songhay and Jolof empires. Institutions from the Mali Empire also survived in the 19th century army of Samory Ture who saw himself as the heir to Old Mali's legacy.

Origin

[edit]The Mandinka military and military culture were crucial to the success of the Mali Empire. The Mandinka were early adopters of iron in West Africa, and the role of blacksmiths was one of great religious and military prestige among them. Manipulation of iron had allowed the Mandinka to spread out over the borders of modern-day Mali and Guinea by the 11th century. During this time, the Mandinka came into contact with the Soninke of the formidable Wagadou Empire. The Soninke formed the first major organized fighting force in West Africa, and the Mandekalu became a major source of slaves for the empire. To combat Wagadou's slave raids, the Mandekalu took refuge in the mountains between Kri and Kri-Koro around Niagassala.[3] There they used the high ground that could provide a better view of arriving armies.[4]

Another response to Soninke pressure could have been the formation of hunters associations by the Mandekalu, which doubled as defense associations. The hunters associations formed the basis of the army that were later federated under a "master of the bush" called the Simbo. The power and prestige of the Simbo, who held both military and religious power, allowed these individuals to become petty kings. After the fall of Wagadou, these petty kings would unite under Sundjata and lead him to victory at the Battle of Kirina.[4]

Historical researchers also claim the technical reason for the empire's rapid expansion was supported by the strong blacksmith and metallurgy culture of Manden. Both smelting and smithing required large quantities of wood to make charcoal for fuel. The blacksmith's activity helped the warriors by smithing fine weapons made of metals, as well as extending the boundaries of their empire by moving further and further afield in search of wood to sustain their industry. The deforestation that resulted from extensive smelting and concentrated smithing has consequently flattened the woodland savannah soils and also inadvertently helped the cavalry soldiers of Manden to move easier in spacious fields, thus creating symbiosis between the cavalry and blacksmiths.[5]

13th century organization

[edit]The emperor or mansa was, at least in theory, head of the armed forces. However, Sakura seems to have been the only mansa to take the field other than Sundjata. Even when Sundjata was fighting, his title was that of "mari" meaning prince,[6] making Mansa Sakura and Mansa Mahmud IV the only sitting mansas ever to lead an army.

Ton-Tigi

[edit]Mansa Sundjata is credited with organizing the early empire's army into 16 clans whose leaders were to protect the new state.[7] These 16 were known as the "ton-ta-jon-ta-ni-woro", which translates as "the sixteen slaves that carry the bow".[8] These "slaves" were actually high nobles dedicated to serve Mali by bringing the bow or quiver (traditional symbols of military force) to bear against the emperor's enemies. Each member was known as a ton-tigi or ton-tigui ("quiver-master") and was expected to fight as cavalry commanders.[2]

Another explanation regarding the term of Ton was not necessarily describe as an actual slave[9][10][11]

Mandekalu horsemen

[edit]Alongside the ton-tigi were horon cavalrymen.[12] These horon were from elite society and included princes or other kinds of nobility.[13] Because of the high price of Arab horses, Mandekalu horsemen were equipped by the ton-tigi or the mansa with their mount.[14] Cavalry fought with lances, sabers and long swords.[2] Imported chain mail and iron helmets would also be available to Mali's early cavalry. With control of trade routes from the Savannah to North Africa, the Mandekalu were able to build up a standing cavalry of around 10,000 horsemen by the reign of Mansa Musa.[13] With such a force, the mansa was able to project his power from modern Senegal to the borders of present-day Nigeria.

Kèlè-Koun

[edit]The ton-tigi, for all intents and purposes, were feudal lords and the only men in the early empire that could afford horses.[12] Infantry leadership, however, fell to the kèlè -koun ("war-head"). A kèlè-koun commanded a unit of infantry known as a kèlè -bolo ("war-arm"). The men under a kèlè-koun's command were all horon ("freemen"), like the ton-tigi and kèlè-koun.[15] At least initially, jonow ("slaves") were barred from military service except as military equipment carriers for the ton-tigi. It was not until after Mali's zenith that jonow battalions were utilized.[2]

Mandekalu infantry

[edit]The exclusion of jonow from the early imperial army increased pressure on the horon to serve. Each tribe in the empire was expected to furnish a quota of horon to fight for the mansa.[16] The core of the army, which may have reached 90,000 men,[17] was Mandinka. However, the mansa reserved the right to call up levies from conquered peoples on the rare occasion this was needed. All horon were expected to arm themselves. It was a point of honor to appear with your own weapons,[18] some of which might be family heirlooms.[19] Javelins called "tamba" were thrown out ahead of close-combat.[12] The majority of infantry were bowmen who used Soninke knowledge of poisons to make up for their arrow's lack of force.[20] Stabbing spears and reed shields were also used by horon, while a kélé-koun might be armed with a locally made saber. Leather helmets were manufactured locally for both cavalry and infantry.[21]

Organization after the 14th century

[edit]The military culture and organization of the Mali Empire grew in power and sophistication until reaching its peak between 1250 and 1450.[22] This period was marked by a firmer, more complex system of military roles in the empire. The reasons for the changes in imperial Mali's army are not known for certain, but it is likely that the expanding size of the state had much to do with its transformation.

Farari

[edit]By the time Ibn Battuta visited the Mali Empire during the reign of Mansa Suleyman, an elite corps among the military was present at court.[23] These men were an outgrowth of the ton-tigui that had fought alongside Sundjata and his immediate predecessors known as the farari ("braves").[24] Each farariya ("brave") was a cavalry commander with officers and warriors beneath him. However, the roles of the farariya were not all identical.[25] Farari served as ton-tigi of the Gbara,[26] governors of far off provinces or simply field commanders.[27] Many forms of the farariya titles would be used by Mali's successor states such as Songhay.[28]

Farima

[edit]One type of farariya, and likely the most common, was the farima ("brave man").[24] A farima, also known as a farin or faran, was very similar to the European knight in his function at the Mandinka court. He was foremost a military leader, commanding from horseback a unit of cavalry. The kèlè-koun reported directly to him on the battlefield and used infantry forces in concert with the farima's cavalry.

The farima, like all farari, reported directly to the mansa who went out of his way to lavish awards on him in the form of special trousers (the wider the seat, the higher the merit) and gold anklets.[14] A farima was part of Mali's warrior aristocracy. He was always present at court, though not necessarily a ton-tigi. He "owned" land and held jonow, which accompanied him to war in much the same fashion as they had his predecessors. In some regions, a farima served as a permanent military governor.[29] A prime examples of this is the Farim-Kabu encountered by the Portuguese during Mali's decline.[30] However, unlike other Farari who governed lands, a farima had to be of the horon.

Farimba

[edit]Another type of farariya was the Farimba ("great brave man"), also known as the farinba or farba. In contrast to the farima, a farimba could be of the horon (usually a royal relative) or of the jonow.[31] In fact, it was quite common and sometimes prudent for a mansa to appoint a jonow as the farimba of particularly wealthy province or city. Jonow depended entirely on their master, in this case the mansa, for their position. Thus, their loyalty was hardly ever in question.[14]

Ibn Khaldun translates this title as deputy or governor, but it is more complex than that. The Farimba was a civilian role akin to an imperial resident like those used by the British Empire centuries later. The farimba was present at vassal courts to oversee local rulers and ensure that local policy did not interfere with that of the mansa.[27] The farimba could take over the court if he judged the vassal lord to be out of step with the mansa's wishes, and he kept a small army garrisoned inside the provincial capital for just such an occasion.[18]

Duukunasi

[edit]The farimba could also use this force to assist local rulers in defending the province. If actually called to the field, which was not likely, the farimba commanded the cavalry. Directly beneath the farimba was the dùùkùnàsi or dougou-kounnasi ("impressive man at the head of the land"), who commanded an infantry force.[18] Unlike the regular army, which was led by the farima and kèlè-koun, these garrison forces were mostly and sometimes entirely slaves.[18]

Sofa

[edit]

All farari, like the ton-tigui of Sundjata's generation, were accompanied by jonow who followed on foot and cared for their master's horses.[32] These jonow were known as sofas, and they would have supplied their ton-tigui with extra javelins in the middle of battle or guarded his getaway horse if retreat was necessary.[33] In fact, the word sofa translates as "horse father" meaning guardian of the horse.[34]

The role of the sofa in Malian warfare changed dramatically after the reign of Sundjata from mere baggage handler to full-fledged warriors. A sofa was equipped by the state, whereas the horon brought their weapons. Sofa armies could be used to intimidate unfaithful governors, and they formed a majority of the infantry by the 15th century.[18] So though imperial Mali was initially a horon-run army, its reliance on jonow as administrators (farimba) and officers (dùùkùnàsi) gradually transformed the character of its military.

Command of the army

[edit]One of the biggest differences between the Mandinka army of Sundjata in the 13th century and that of Sulayman in the 14th century is the division of the entire army between two farari along geographic lines. According to chroniclers of the time, imperial Mali had a northern command and a southern command under the Farima-Soura and Sankaran-Zouma, respectively.[1] Both served as ton-tigui on the Gbara, and their influence was immense. In fact, the refusal of both the Farima-Soura and the Sankaran-Zouma to follow Mansa Mamadu to battle at the siege of Jenne in 1599 resulted in Mamadu's failure.[35]

Farima-Soura

[edit]The Farima-Soura, also documented as the Farim-Soura, Faran-Soura or Sura Farin appears to have been a field commander in charge of the northern border. Soura was likely a province or at minimum a large region if the title of the Farim-Kabu is any evidence. His main responsibility would have been monitoring the Saharan border for bandits to keep merchants from being molested.

Sankar-Zouma

[edit]The head of the Kondé clan ruled the Sankarani River region near the imperial capital of Niani.[18] The title of Sankar-Zouma, also known as Sankaran-Zouma, is derived from the region and is unique among the farari. The Sankar-Zouma held command over all forces in the south bordering the coastal jungle. His role would have been similar to the Farima-Soura in protecting merchants moving in and out of the empire with valuable goods. He had many goods which he would consistently give out to others.

Pre-imperial expansion

[edit]

The first major test of the Mandinka war machine was the war against Soumaoro Kante and his Sosso kingdom. Mari Djata utilized the infantry resources of his allies within and outside of Manden proper to best the Sosso in several confrontations, culminating in the Battle of Krina circa 1235. Oral historians recount the use of poison bowmen from the south in Do (along what is now the Sankarani River), fire archers from Wagadou to the north, and heavy cavalry from the northern state of Mema. These elements were then complemented by Mandinka "smiths", clans which specialized in the production and use of iron weapons such as spears and swords. After Djata's victory at Kirina, the Mandekalu forces quickly moved on to take the rest of the Sosso areas left leaderless upon Soumaoro's disappearance. If the chronicles of the djeli are to be taken seriously (and many modern historians do), this involved a series of sieges against fortified towns throughout the northern half of Manden proper.

Djata’s conquests

[edit]The first settlement to fall was Soumaoro's capital called Sosso. The Mandekalu attacked at dawn using fire archers from Wagadou as well as ladders shielded by infantry. Once the city gate had fallen, the Sosso forces were massacred and the town's leader, Noumounkeba, enslaved. The town was burnt to the ground. Djata's army moved onto Diafunu,[36] which was also taken in the morning. The town was spared the torch, but all its young men were forced into the army upon having their heads shaved. The last town to fall to Mari Djata was Kita,[36] which fell without much struggle after an early morning assault. The leader of the town was killed, but no massacre or enslavement followed. Oral historians explain this by citing that the Mandinka clan of Kamara lived in the area.[citation needed]

Campaigns of Fakoli and Fran

[edit]While Djata was busy consolidating Mandinka power in the north, two of his generals were busy campaigning elsewhere. Fakoli of the Koroma clan took one-third of the army out to conquer the town of Bambougou within the Bambouk area, which was famous for its goldfields.[37] Meanwhile, Fran of the Kamara clan took one-third of the army into Fouta Djallon.[38] Many Kamara clans of northern Guinea point to Fran as their common ancestor.

Early imperial expansion (1235–1300)

[edit]After the elimination of the Sosso threat and his selection by the Mandekalu clans as mansa of Manden, Djata sought to re-equip his army with horses from Jolof, a region and realm of Senegal that had sided with Soumaoro in Manden's war of independence. However, this too would result in conflict for his fledgling army.

Tiramakhan's western campaign

[edit]Tiramakhan, also known as Tiramaghan, of the Traore clan, was ordered by Sonjata to bring an army west after the king of Jolof had allowed horses to be stolen from Mandekalu merchants. The king of Jolof also sent a message to the young emperor referring to him as an upstart.[39] By the time Tiramakhan's forces were done three kings were dead, and the Jolof ruler was reduced to a vassal.[40] The new western portion of the empire settlement would become an outpost that encompassed not only northern Guinea-Bissau but the Gambia and the Casamance region of Senegal (named for the Mandinka province of Casa or Cassa ruled by the Casa-Mansa).[41] It was in this way that the sub-kingdom of Kaabu was established. The Traore clan left a large imprint on Guinea-Bissau and future settlements along the Gambia which trace their noble bloodlines back to him or other Mandekalu warriors.[42]

Expansion under Mansa Ouali I

[edit]Mansa Djata died in around 1255,[43] and he was succeeded by his son who ruled until 1270.[44] Mansa Ouali I (also known as Ali, Uli or Wali) proved to be able and energetic leader according to Ibn Khaldun. During his reign, the Mandinka conquered or absorbed Bundu near the Senegal River.[43] The empire also conquered the city of Gao, epicenter of the burgeoning Songhai state, and brought Timbuktu and Jenne into its ambit if not its actual control.[45]

Civil war and rebellion

[edit]The end of Mansa Ouali's reign signaled a downturn in the fortunes of the Mali Empire. Mansa Ouati, an adopted son of Mansa Djata,[46] ruled from 1270 to 1274.[47] During this period, Manden was racked by civil war between Ouati and another adopted brother by the name of Mansa Khalifa. Both princes were the sons of former generals and would have had sizeable forces under their command.[46] Mansa Ouati died in 1274, and Khalifa promptly marched in to take the throne. Though his ascension meant an end to the destructive civil war, the Mali Empire was weaker than at any time since the rise of Mansa Djata. During the despotic rule of Khalifa, the Songhai residents of Gao province were able to throw off Mandinka rule.[48] After exhibiting cruelty and madness, courtiers had Khalifa assassinated.[49] He was followed by Mansa Abu Bakr, grandson of Sunjata.[50] Mansa Abu Bakr was capable of keeping the rest of Manden together, but either did not attempt or was unable to bring Gao back into the fold.

Re-conquest and expansion under Mansa Sakura

[edit]Mansa Abubakari I was usurped by general and former slave Sakura or Sabakura in 1285.[44] The Mali Empire expanded under his personal leadership, making him unique among the early mansas. He conquered the ancient state of Tekrour,[51] which encompassed parts of modern Senegal and Mauritania. Mansa Sakura then took the army north and captured Takedda,[51] bringing many desert nomads under Mandinka domination. The mansa even brought the Songhai back under control, re-subjugating the kingdom of Gao.[49] Mali's warrior emperor not only restored the state to its former glory but made it more powerful than ever. By the time of his murder in 1300,[44] the Mali Empire already stretched from the Atlantic to the border of the Kanem Empire.

The empire at its zenith (1300–1340)

[edit]The territorial gains of the Mali Empire were maintained well after Sakura's death. Mansas Gao, Mohammed ibn Gao and Abubakari II reigned in peace and prosperity over a well-guarded realm dotted with garrisons in Walata, Timbuktu, Gao, Koumbi-Saleh and many others.[52] In 1312, Mansa Musa I came to power and brought the empire even more fame and prestige with his legendary Hajj to Mecca. His generals added Walata and the Teghazza salt mines to the empire's already impressive size.[51] In 1325, the Mandinka general Sagmandir put down yet another rebellion by the Songhai in Gao.[51] The Mali Empire was at its largest and wealthiest under Musa I, spanning over 1.29 million square kilometers.[53]

The fragmenting empire (1340–1440)

[edit]

The Mali Empire has enjoyed virtually no military reverses in its first century of existence and had grown at a terrific rate in both size and wealth by the time Ibn Battuta arrived there. However this wealth and power may have been the reason behind more aggressive attacks by its neighbors as well as the complacency of some of the mansas in dealing with them. Subject peoples on the fringes of the empire slowly began to shake off the yoke of Mandinka hegemony. This happened slowly at first, but after 1450 the empire would begin to crumble very rapidly.

The secession of Gao and the Mossi raids

[edit]Mansa Musa was succeeded by his son in 1337, which marked the beginning of the empire's slide into decline. Mansa Maghan ruled four years before his death, which was probably hastened by Musa's brother Suleyman. Sometime during these four years, Mossi horsemen from the Upper Volta raided Timbuktu and surrounding cities. But the most important development of the period was Songhai's assertion of independence for good from Mali in 1340.[54]

The Jolof empire

[edit]The next vassal kingdom of Mali to break away was the province of Jolof. The Wolof inhabitants of this kingdom united under their own emperor and formed the Jolof Empire around 1360 during a succession crisis that followed the death of Mansa Suleyman.[55] It is unknown exactly why the Wolof broke away, but the destructive reign of Suleyman's predecessor and nephew Maghan I may have played a role in Jolof's motives if not the very reason why future mansas could not do anything about it.

The eastern revolt

[edit]Mansa Suleyman died in 1360 and was succeeded by his son, Camba, who was quickly overthrown by a son of Maghan I. Despite turmoil within Manden, the empire maintained its other possessions. The throne officially went to Mansa Musa II in 1374, son of Mansa Mari Djata II. However, Musa II, while a good emperor according to written records, was under the control of his sandaki (literally "high counselor",[56] often translated as vizier).[57] This sandaki, named Mari Djata, had no relation to anyone in the Keita dynasty, but ran the empire as if he was. According to Ibn Khaldun, Sandaki Mari Djata even tossed Musa II in jail keep him out of the way.[58] During this time, Mali's eastern provinces were in open rebellion.[59] Sandaki Mari Djata mobilized the army on a campaign to restore order. He oversaw the re-subjugation of the Tuareg occupying Takedda,[60] an important copper mining center in the north.[61] The vizier was not entirely successful and was unable to stop re-subjugate the Songhai who were well on their way to their own empire by the end of the 14th century.[2] Attempts to re-conquer the Songhai were likely doomed due to the inhabitants being under Mandinka military influence for so long and being ruled by a dynasty that had its very roots in Mali's imperial court.[62] The Mali Empire also laid siege to the town of Tadmekka east of Gao but was unable to take the town or force its inhabitants back into submission.[59] The overall success of the campaign appears mixed, but Mali's ability to retain Takedda shows it was far from total collapse.

The Sandaki usurpation and second Mossi raid

[edit]Musa II was succeeded by his brother, Maghan II, in 1387. This reign would only last two years due to him being killed by his predecessor's sandaki. This murder was avenged by Maghan III who ruled from 1390 to 1404. In 1400,[63] the Mossi state of Yatenga under emperor Bonga takes advantage of Mandinka disunity yet again and raids the town of Masina.

The Diawara revolt

[edit]During the early 15th century, Mali suffered a violent revolt in its northern province of Difunu or Diara. At the time, the Niakhate dynasty had run the province in the name of the mansa.[64] Diafunu had long been a part of the Mali Empire and was crucial to the mansa's northbound trade caravans. A new dynasty under the name Diawara killed the Niakhate vassal and asserted independence from Mali.[64]

The Tuareg invasion

[edit]Mansa Musa III came to power after Maghan III. His reign began with the conquest of Dioma under his given name of Sérébandjougou alongside his brother and heir Gbèré.[46] After conquering Dioma, he was put on the throne as Foamed Musa or Musa III. Despite starting out on a markedly positive note, Musa III's reign would be one of many losses for the Mali Empire. In 1433, the Tuareg launched a major invasion from the north capturing Timbuktu,[65] Arawan and Walata.[63] The important city-state of Jenne was independent of Mali by 1439.[66] The Mali Empire loss almost all access to the Saharan trade routes without which it could not get enough horses to take the centers back or preserve its own precarious position. The mansas were thus forced to look south for their economic security.

The empire on the defensive (1440–1490)

[edit]With the exception of the Mossi states to its south, the Mali Empire faced very few external threats throughout its existence. Even after its glory days had passed, the mansas were generally concerned with holding onto subject peoples rather than outright invasions. That all changed during the reign of Mansa Uli II in the mid-15th century. For the next 150 years, the Mali Empire would be locked in a life or death struggle for its very existence amid a barrage of enemies on all sides.

The Portuguese

[edit]The first unfamiliar threat to Mali came not from the jungles or even the desert but the sea. The Portuguese arrived on the Senegambian coast in 1444,[67] and they were not coming in peace. Using caravels to launch slave raids on coastal inhabitants,[68] the Malian vassal territories were caught off guard by both vessels and the raiders within them. However, the Mali Empire countered the Portuguese raids with fast shallow-draught watercraft. The Mandekalu inflicted a series of defeats against the Portuguese due to the former's expert war archers, and their use of poison arrows. The defeats forced Portugal's king to dispatch his courtier Diogo Gomes in 1456 to secure peace. The effort was a success by 1462, and trade became Portugal's focus along the Senegambia.[69]

Songhai hegemony

[edit]While the coastal threat had been abated, an even more dangerous problem arrived on the empire's northern and eastern frontier in the form of an imperial Songhai state under the leadership of Sonni Ali. In 1465, Songhai forces under Sulaiman Dama (also known as Sonni Silman Dandi)[70] attacked the province of Mema, which had seceded from Mali in the first few decades of the 15th century.[71] The Songhai Empire also captured Timbuktu in 1468,[72] which had already fallen out of the Mali Empire's hands. The Songhai also took Jenne out Mali's sphere of influence in 1473. By then the message that Songhai was sending Mali was clear indeed; if the mansa could not hold onto his provinces, Songhai would. The Mossi kingdom of Yatenga felt it could raid the Songhay Empire as it had the Mali Empire in the past. It snatched BaGhana province from Songhay occupation in 1477 then raided Tuareg-controlled Walata in 1480.[73] The Songhay proved tougher customers and handed Yatenga's King Nasere a crushing defeat in 1483 effectively ending Mossi incursions in the Niger valley.[72]

The start of the Tengela war

[edit]Mali was powerless in the north, and its economic, military and political concentration shifted further west in the face of seemingly unstoppable Songhay aggression. For decades, the pastoral Fulbe had been growing in power in and round Mali's remaining provinces. One especially ambitious Fulbe chieftain named Tengela would launch a war against both Mali and Songhay that lasted from 1480 to 1512.[74] Tengela began by setting up a base in Futa Jallon led by his son, Koly Tengela. Meanwhile, the elder Tengela built up an impressive army of dissident Fulbe, which included cavalry.[74] At the same time, Songhay forces had been moving westward in hopes of capturing Mali's Bambuk goldmines.[74]

Mansa Uli II was succeeded by Mansa Mahmud II in 1481. He received an envoy from King John II of Portugal that year, but it resulted in nothing of benefit for the bedeviled emperor.[74] Fearing his situation was untenable, he sought the protection of the Ottoman Turks but was refused.[44] The Mali Empire had never reached out to any outside power for help before, and 1481 is truly a low-point in Mali's history. Still there was much more to come.

In 1490, Tengela led the Fulbe out of Futa Jallon forcing the Malian forces to retreat to the Gambia. He was now threatening the lines of trade and communication between the Malian heartland and its last remaining economic artery. Tengela continued his advance until he reached Futa Tooro, where he set up his base of operations.[75]

Mansa Mahmud II, known as Mamadou in Portuguese accounts, sought out Portuguese assistance or at least firearms that same year. The Portuguese responded in 1495 by sending an envoy laden with gifts but no weapons.[74] Firearms in the hands of the Mali Empire might have changed the history of West Africa, if their track record with native weapons is anything to go by. However, Mali never became a gunpowder state, and the military Mahmud II passed onto his son in 1496 was virtually the same as the one inherited by Musa I in 1312.

Collapse of the Mali empire (1500–1600)

[edit]

Portugal did far more than hinder Mali's attempts to modernize its army. They also undermined the empire's authority along a coast that was getting farther and farther from the influence of Niani's court thanks to the Tengela incursions.[74]

Songhay hegemony in the Sahel

[edit]The threat from the Songhay Empire became a far graver matter during the reign of Mansa Mahmud III. From 1500 to 1510, Askia Muhammad's forces picked apart Mali's remaining provinces in the Sahel. Around 1499,[76] the Askiya conquered Baghana province from Mali despite the latter's Fulani allies.[77] In 1500 or 1501, Songhay conquers Diala (also known as Dyara) near Kaarta and pillages a royal residence there.[64] Askia Muhammad then defeats the Malian general Fati Quali in 1502, putting Songhay in possession of Diara in Diafunu province.[77] In 1506, Askia Muhammad raids Galam on the Senegal river, wiping away the last vestiges of Mali's rule in the Sahel.[64] While Songhay does not permanently occupy the Senegal, the raid effectively takes it out of the hands of the mansa.[76] Songhay's hold on the area was still contested by Mali, but it was Tengela who made the most historic challenge to Songhay's control in the area. In 1512, Tengela invaded Diara, which called on the Songhay to defend them. The fact that they called on Songhay instead of Mali says just how much prestige the mansa had lost in the region. Songhay responded with an expedition under Kurmina-fari Umar Komdiagla (also known as Amar Kondjago), a brother of Askia Muhammad.[74] In the ensuing battle, Tengela was defeated and killed bring an end to the Tengela War.[75]

The Songhay respite and the battle for Bambuk

[edit]After 1510, the Mali Empire received a brief respite from Songhay attacks as their enemy was overcome with a series of typical imperial challenges. The same provincial revolts and dynastic disputes that has troubled Mali left Songhay incapable of raiding into Mali for nearly thirty years.[70] While the askiyas were occupied, Portugal sent another emissary to Mali, this time from their post at El Mina in what is now Ghana. Mansa Mahmud III attempted to gain military assistance as his father had done before him, but to no avail.[44] The Portuguese were only interested in re-securing trade interests with Mali along the Gambia.[78] That same year, Koli Tengela launched an attack on Bambuk in hopes of gaining the goldfields so coveted by his father and Songhay. Mali defeated him there, driving the Fulbe back into Futa Toro.[75]

The rise of Kaabu

[edit]In 1537, the farimba of Kaabu severed ties with the Mali Empire to form his own state. This left Mali in control of little more than its own Mandinka heartland.[79] The Kaabu Empire would carry on much of Mali's military tradition, but they would reserve the title of mansa for themselves from now on. By 1578 they had absorbed Mali's coastal provinces of Casa and Bati cutting off Mali from trade with Portugal.[30]

The sack of Niani

[edit]The accession of Askiya Isma’il in 1537, marked the end of peaceable relations between Songhay and Mali.[70] They renewed attacks on their old rival until they reached central Mali. Finally in 1545, Mansa Mahmud III was forced to flee the capital of Niani as Kurminafari (and later Askia) Dawud sacked the city.[80] Upon the advice of his brother Askiya Ishaq, Dawud did not chase the mansa's smaller force into the mountains and hills and instead bivouacked in the city for some seven days. During this time, Kurminafari Dawud announced to his soldiers that whoever wished to answer a call of nature should do so in the royal palace. By the seventh day, the entire palace was filled with excrement despite its great size.[81] Mali's humiliation was now complete.

Further losses

[edit]In 1558, Askiya Dawud launched a raid on the Malian town of Suma. He followed this up that same year by defeating the Malian general Ma Kanti Faran at Dibikarala.[82] Then in 1559, during the last year of Mansa Mahmud III's reign, Koli Tengela in 1559, Koli set up his capital at Anyam-Godo in Futa Toro and turned the region into what would later be called the Denianke Kingdom.[74]

Battle of Jenné

[edit]

Following Songhai's defeat by a Moroccan invasion in 1591 at the Battle of Tondibi, the Mali Empire was released from a century's-old pressure on its northern frontier. In place of the Songhai Empire succeeded a much weaker authority on the Niger in the form of the Arma, separated from Mali by warring chiefdoms.[80]

Mansa Mahmud IV tried to take advantage of the situation with the support of Fulbe and Bambara chiefs.[83] In 1599, the mansa led this army in a march on Battle of Jenné.[80] The rulers of Jenné called on the Moroccan garrison of Arma in Timbuktu for reinforcements. The other obstacle to the mansa's success was his betrayal by a major ally prior to the battle. The reasoning behind this betrayal, according to Mandinka oral traditions was that Mahmud IV did not have the support of Mali's traditional generals, the Farim-Soura and Sankar-Zouma. This major ally of the mansa abandoned him at the last moment and went over to the Moroccans and advised them on what to expect from the mansa's army.[83] Despite their amazement at the size of the mansa's force, the Arma won the battle after a violent bombardment.

The remaining provinces of Mali freed themselves one by one giving rise to 5 small kingdoms. The most prominent of them were brought together to form the basis of the Bambara kingdoms of Segu and Kaarta. Mali itself was reduced to a small kingdom around Kaabu and Kita.[83] By 1600 the Denianke controlled all the area from the Sahel to Futa Jallon and over the upper Senegal. They would also take the coveted Bambuk goldfields and the important commercial town of Diakha on the Bafing River.[75] The battle of Jenne put the final nail in the empire's coffin. A victory at Jenne might well have saved the empire, keeping the tribes united under a strong and proven leader. But Mansa Mahmud IV retired to the remains of his kingdom and with his death, the realm was split up among his three sons. A unified Mali simply ceased to exist. The last remnants of Mali were destroyed by the Bambara in the 17th century.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Hunwick, page 15

- ^ a b c d e Taher, page 815

- ^ Camara 1977, page 15

- ^ a b Diakité, page 209

- ^ Goucher; LeGuin; Walton, Candice; Charles; Linda. ""Trade, Transport, Temples, and Tribute: The Economics of Power," in In the Balance: Themes in Global History" (PDF). ANNENBERG LEARNER. The Annenberg Foundation 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cooley, page 62

- ^ Niane 1984, p. 134.

- ^ Akinjogbin, page 133

- ^ Sisòkò, Fa-Digi; William Johnson, John; Bird, Charles Stephen (1997-01-01). African epic series /Thomas A. Hale and John W. Johnson éd African epic series. Indiana University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-85255-094-6.

- ^ Johnson, John William; Sisòkò, Fa-Digi; Bird, Charles Stephen (2003). Son-Jara. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34337-2.

- ^ Quotation of Encyclopaedia of Islam: New Edition(1960), Vol 6, page 1215: "Bilal bin Rabah, sometimes called Ibn Hamama after his mother, is referred to in Mali as Jon Bilali, "Slave Bilali." One of the bards from whom I collected, Ban Sumana Sisoko, explained the jon, "slave," by stating a religious connotation in the same sense as the Arabic name of 'Abd Allah(Slave/servant of God)

- ^ a b c Diallo, page 6

- ^ a b Sarr, page 92

- ^ a b c Taher, page 828

- ^ Ki-Zerbo, page 133

- ^ Taher, page 818

- ^ Taher, page 813

- ^ a b c d e f Camara 1992, page 69

- ^ Thornton, page 26

- ^ Thornton, page 27

- ^ Thornton, page 25

- ^ Oliver & Atmore, page 62

- ^ Charry, page 357

- ^ a b Cooley, page 77

- ^ Cooley, page 75

- ^ Charry, page 358

- ^ a b Niane 1984, p. 135.

- ^ Hunwick, page xxix

- ^ Niane, page 85

- ^ a b Mansour, page 38

- ^ Oliver, page 387

- ^ Roberts, page 222

- ^ Smith, page 50

- ^ Roberts, page 37

- ^ Hunwick, page 16

- ^ a b Niane 1984, p. 133.

- ^ Taher, page 811

- ^ Niane, page 70

- ^ Cô-Trung, page 130

- ^ Austen, page 93

- ^ Vigh, page 40

- ^ Oliver, page 456

- ^ a b Stride & Ifeka, page 49

- ^ a b c d e Houtsma, page 241

- ^ Turner, page 19

- ^ a b c Niane, D.T.: "Recherches sur l’Empire du Mali au Moyen Âge". Presence Africaine. Paris, 1975

- ^ Taher, page 808

- ^ Oliver, page 379

- ^ a b Oliver, page 380

- ^ Niane 1984, p. 147.

- ^ a b c d Stride & Ifeka, page 51

- ^ Taher, page 812

- ^ Hempstone, page 312

- ^ Haskins, page 46

- ^ Barry 1992, p. 263.

- ^ Cooley, page 66

- ^ Cooley, page 69

- ^ Cooley, page 65

- ^ a b Taher, page 826

- ^ Stride & Ifeka, page 54

- ^ Niane 1984, p. 150.

- ^ Hunwick, page xxxvi

- ^ a b Stride & Ifeka, page 55

- ^ a b c d Oliver, page 431

- ^ Oliver & Atmore, page 67

- ^ Oliver, page 439

- ^ Mansour, page 33

- ^ Shillington, page 921

- ^ Thornton, page 23

- ^ a b c Oliver, page 420

- ^ Stride & Ifeka, page 67

- ^ a b Cissoko 1984, p. 191.

- ^ Laude, page 64

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shillington, page 922

- ^ a b c d Oliver, page 458

- ^ a b Jam, page 70

- ^ a b Stride & Ifeka, page 73

- ^ Ly-Tall 1984, p. 183.

- ^ Wondji 1992, p. 389.

- ^ a b c Oliver, page 455

- ^ Hunwick, page 140

- ^ Hunwick, page 148

- ^ a b c Ly-Tall 1984, p. 184.

Works cited

[edit]- Akinjogbin, I.A. (1981). Le Concept de pouvoir en Afrique. Paris: Unesco. pp. 191 Pages. ISBN 92-3-201887-X.

- Austen, Ralph A. (1999). In Search of Sunjata: The Mande Oral Epic As History, Literature and Performance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 352 Pages. ISBN 0-253-21248-0.

- Barry, B. (1992). "Senegambia from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century: evolution of the Wolof, Sereer and 'Tukuloor'". In Ogot, B. A. (ed.). Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. General History of Africa. Vol. 5. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 262–299. ISBN 92-3-101711-X.

- Camara, Seydou (1977). "Le Manden des origins à Sunjata." Mémoire de Fin d'Etudes en Histoire-Géographie. Bamako: Ecole Normale Supérieure. pp. 84 Pages.

- Camara, Sory (1992). Gens de la parole: Essai sur la condition et le role des griots dans la société malinké. Paris: KARTHALA Editions. pp. 375 Pages. ISBN 2-86537-354-1.

- Charry, Eric S. (2000). Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 500 Pages. ISBN 0-226-10161-4.

- Cissoko, S. M. (1984). "The Songhay from the 12th to the 16th century". In Niane, D. T. (ed.). Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. General History of Africa. Vol. 4. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 187–210. ISBN 92-3-101-710-1.

- Cô-Trung, Marina Diallo (2001). La Compagnie Générale des Oléagineux Tropicaux en Casamance 1948–1962. Paris: Karthala Editions. pp. 519 Pages. ISBN 2-86537-785-7.

- Cooley, William Desborough (1966). The Negroland of the Arabs Examined and Explained. London: Routledge. pp. 143 Pages. ISBN 0-7146-1799-7.

- Diakité, Drissa (1980). "Le Massaya et la société Manding." Essai d'interprétation des lutes socio-politiques qui ont donné naissance à l'empire du Mali au 13ème siècle. Paris: Université de Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne. pp. 262 Pages.

- Diallo, Boubacar Séga (2007). Armées et Armes dans les empires du Soudan Occidental. Bamako: l’Université de Bamako. pp. 11 Pages.

- Hempstone, Smith (2007). Africa, Angry Young Giant. Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing, LLC. pp. 664 pages. ISBN 978-0-548-44300-2.

- Hunwick, John (1988). Timbuktu & the Songhay Empire: Al-Sa'dis Ta'rikh al-sudan down to 1613 and other Contemporary Documents. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 480 pages. ISBN 90-04-12822-0.

- Ki-Zerbo, Joseph (1978). Histoire de l'Afrique noire: D'hier a demain. Paris: Hatier. pp. 731 Pages. ISBN 2-218-04176-6.

- Ly-Tall, M. (1984). "The decline of the Mali Empire". In Niane, D. T. (ed.). Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. General History of Africa. Vol. 4. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 172–186. ISBN 92-3-101-710-1.

- Mansour, Gerda (1993). Multilingualism and Nation Building. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. pp. 160 Pages. ISBN 1-85359-174-2.

- Niane, D.T. (1975). Recherches sur l'Empire du Mali au Moyen Âge. Paris: Présence Africaine. pp. 112 Pages.

- Niane, D. T. (1984). "Mali and the second Mandingo expansion". In Niane, D. T. (ed.). Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. General History of Africa. Vol. 4. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 117–171. ISBN 92-3-101-710-1.

- Niane, D.T. (1994). Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali. Harlow: Longman African Writers. pp. 101 Pages. ISBN 0-582-26475-8.

- Oliver, Roland (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa Volume 3 1050 – c. 1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 816 Pages. ISBN 0-521-20981-1.

- Oliver, Roland & Anthony Atmore (2001). Medieval Africa 1250–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 251 Pages. ISBN 0-521-79372-6.

- Roberts, Richard L. (1987). Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700–1914. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 293 Pages. ISBN 0-8047-1378-2.

- Sarr, Mamadou (1991). L'empire du Mali. Bamako: Impr. M.E.N. pp. 100 Pages.

- Sauvant, Le P. (1913). Grammaire Bambara. Alger: Maison-Carrée. pp. 239 Pages. OCLC 26020803.

- Shillington, Kevin (2004). Encyclopedia of African History, Vol. 1. London: Routledge. pp. 1912 Pages. ISBN 1-57958-245-1.

- Smith, Robert S. (1989). Warfare & Diplomacy in Pre-Colonial West Africa Second Edition. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 164 Pages. ISBN 0-299-12334-0.

- Stride, G.T. & C. Ifeka (1971). Peoples and Empires of West Africa: West Africa in History 1000–1800. Edinburgh: Nelson. pp. 373 Pages. ISBN 0-17-511448-X.

- Taher, Mohamed (1997). Encyclopedic Survey of Islamic Dynasties A Continuing Series. New Delhi: Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. pp. 857 Pages. ISBN 81-261-0403-1.

- Thornton, John K. (1999). Warfare in Atlantic Africa 1500–1800. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 194 Pages. ISBN 1-85728-393-7.

- Turner, Richard Brent (2004). Islam in the African-American Experience. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 336. ISBN 0-253-34323-2.

- Vigh, Henrik (2006). Navigating Terrains of War: Youth and Soldiering in Guinea-Bissau. New York City: Berghahn Books. pp. 258 Pages. ISBN 1-84545-149-X.

- Wondji, C. (1992). "The states and cultures of the Upper Guinean coast". In Ogot, B. A. (ed.). Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. General History of Africa. Vol. 5. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 368–398. ISBN 92-3-101711-X.