Southern Ukraine

Southern Ukraine (Ukrainian: Південна Україна, romanized: Pivdenna Ukraina) refers, generally, to the territories in the South of Ukraine.

The territory usually corresponds with the Soviet economical district, the Southern Economical District of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. The region is completely integrated with a marine and shipbuilding industry.

Southern Ukraine was invaded by the Russian military on February 24, 2022, turning parts of the region into a major theatre of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

Historical background

[edit]The region primarily corresponds to the former Kherson, Taurida, and most of the Yekaterinoslav Governorates which spanned across the northern coast of Black Sea after the Russian-Ottoman Wars of 1768–74 and 1787–92.

The Kurgan hypothesis places the Pontic steppes of Ukraine and southern Russia as the linguistic homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans.[1] The Yamnaya culture is identified with the late Proto-Indo-Europeans.[2] The region has been inhabited for centuries by various nomadic tribes, such as Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans, Huns, Bulgars, Pechenegs, Kipchaks, Turco-Mongols and Tatars.

Before the 18th century, the territory known as the Wild Fields (as translated from Polish or Ukrainian) was dominated by Ukrainian Cossack community better known as Zaporozhian Sich and the realm of Crimean Khanate with its Nogai minions that was a union state of the bigger Ottoman Empire. The Crimean–Nogai slave raids caused considerable devastation and depopulation in the area before the rise of the Zaporozhian Cossacks.[3]

Encroachment of Muscovy (today Russia) in the region started after the 16th century after its expansion along Volga river after the Moscow-Kazan wars and conquest of Astrakhan. Further expansion continued also with Moscow-Lithuania armed clashes.

With start of the Khmelnytsky Uprising within Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in middle of 17th century, Muscovy on pretence of the eastern Orthodoxy protection further expanded its influence down south over Cossack communities of Pontic steppes (lower Don and lower Dnieper) and the Crimean Khan domains.

At the end of 17th century a native Kyivan, bishop Theophan Prokopovych came up with the idea of all-Russian nation referring to the old Rus state founder of which Volodymyr the Great was baptized and accepted Byzantine Christianity (today known as Eastern Orthodoxy) in Chersoneses of Taurida (today in Sevastopol).

In 1686 there was signed the Treaty of Perpetual Peace between Muscovy and Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, after which Muscovy took control over the Left-bank Ukraine, Zaporozhian Sich, and Kyiv with outskirts.

In 18th century there was built Ukrainian line and lands of earlier destroyed Zaporozhian Sich were resettled by Serbs creating territories of New Serbia and Slovianoserbia.

At the end of 18th century following the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Empire and the treaty of Jassy (the Ochakiv Region, area of today's Odesa and Mykolaiv oblasts), the Russian Empire assumed full control of the northern Black Sea coast.

Russian Hellenization of Pontic littoral

[edit]After the Russian-Ottoman Wars of the second half of 18th century (1768–74 and 1787–92) and acquisition of all territory of modern southern Ukraine, number of settlements and cities with Turkic or other names in region were renamed in Greek or Russian manner.

- Acidere → Ovidiopol

- Hacıbey → Odesa

- Orel Sloboda (Catherinine sconce) → Olviopol (today Pervomaisk, Mykolaiv Oblast)

- Domakha → Mariupol (by Balaklava Greeks from outskirts of Bakhchysarai)

- Bilehowisce (Alexander sconce) → Kherson

- Aqyar → Sebastopol (today Sevastopol)

- Kezlev → Yevpatoria

- Kiz-yar → Novo-alexandrovka (Novo-olexandrivka) Sloboda → Melitopol

- Caffa (Kefe) → Theodosia (today Feodosia)

- Aqmescit → Simferopol

- Mykytyn Rih → Slaviansk → Nikopol

- Usivka (Bečej sconce) → Alexandria (today Oleksandriia)

- Sucleia (Sredinnaya fortress) → Tiraspol (in Moldova)

- Czorna → Grigoriopol (in Moldova)

Following the World War II any trace of Crimean Tatar toponymy was predominantly removed in Crimea and Kherson Oblast.

Politics

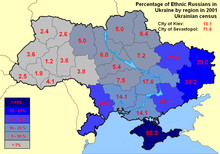

[edit]Russian is spoken by a significant minority in the region, although not to the extent that it is in the three oblasts that comprise eastern Ukraine.[4] Effective in August 2012, a new law on regional languages entitles any local language spoken by at least a 10% minority be declared official within that area.[5] Within weeks Russian was declared as a regional language in several southern and eastern oblasts and cities.[6] Russian could then be used in these cities/oblasts' administrative office work and documents.[7] On 23 February 2014, the Ukrainian parliament voted to repeal the law on regional languages, which would have made Ukrainian the sole state language at all levels even in southern and eastern Ukraine.[8] This vote was vetoed by acting President Turchynov on March 2.[9][10] Nevertheless the law was repealed by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine on 28 February 2018 when it ruled the law unconstitutional.[11]

Noticeable cultural differences in the region (compared with the rest of Ukraine, except eastern Ukraine) are more "positive views" of the Russian language[12][13] and of Joseph Stalin[14] and more "negative views" of Ukrainian nationalism.[15] In the 1991 Ukrainian independence referendum, a lower percentage of the total electorate voted for independence in eastern and southern Ukraine than in the rest of the country.[16][17]

In a poll conducted by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in the first half of February 2014, 19.4% of those polled in southern Ukraine believed "Ukraine and Russia must unite into a single state"; nationwide this percentage was 12.5.[18]

During elections voters of the southern (and eastern) oblasts (provinces) of Ukraine vote for the parties (Communist Party of Ukraine, Party of Regions) and the presidential candidates (Viktor Yanukovych) with a pro-Russian and status quo platform.[19][20][21] The electorate of the CPU and the Party of Regions was very loyal to them.[21] But following the Revolution of Dignity the Party of Regions collapsed[22] and the Communist Party was banned and declared illegal.[23]

Religion

[edit]Religion in south Ukraine (2016)[24]

According to a 2016 survey of religion in Ukraine conducted by the Razumkov Center, around 65.7% of the population of southern Ukraine declared to be believers in any religion, while 7.4% declared to be non-believers, and 3.2% declared to be atheists and agnostics.[24] the study also found that 77.6% of the total southern Ukraine population declared to be Christians (71.0% Eastern Orthodox, 5.1% simply Christians, 0.5% Latin Church Catholics, 0.53% members of various Protestant churches, 0.5% members of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church), and 0.5% were Jewish. Not religious and other believers not identifying with any of the listed major religious institutions constituted about 24.7% of the population.[24]

Oblasts

[edit]| Oblast | Area in km2 | Population (Census 2001) |

Population (1 Jan. 2012) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Odesa Oblast | 33,313 | 2,469,057 | 2,388,297 |

| Mykolaiv Oblast | 24,585 | 1,264,743 | 1,178,223 |

| Kherson Oblast | 28,461 | 1,175,122 | 1,083,367 |

| Dnipropetrovsk Oblast | 31,923 | 3,561,224 | 3,320,299 |

| Zaporizhzhia Oblast | 27,183 | 1,929,171 | 1,791,668 |

| Total excluding Crimea and Sevastopol |

145,465 | 10,399,317 | 9,761,854 |

| Crimea | 26,080 | 2,033,736 | 1,963,008 |

| Sevastopol (city) | 864 | 379,492 | 381,234 |

| Total including Crimea and Sevastopol |

172,409 | 12,812,545 | 12,106,096 |

The neighbouring Kirovohrad Oblast is more often associated with the Central Ukraine. Also Crimea (with Sevastopol City) is reviewed sometimes as a unique region. According to the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, south Ukraine was considered to consist of the territory of the former Kherson, Taurida and Yekaterinoslav Governorates.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Balter, Michael (13 February 2015). "Mysterious Indo-European homeland may have been in the steppes of Ukraine and Russia". Science.

- ^ Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei (2015-06-11). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- ^ Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 0802083900. OCLC 940596634.

- ^ Serhy Yekelchyk Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation, Oxford University Press (2007), ISBN 978-0-19-530546-3, page 187

- ^ Yanukovych signs language bill into law. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ^ Russian spreads like wildfires in dry Ukrainian forest. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ^ Romanian becomes regional language in Bila Tserkva in Zakarpattia region, Kyiv Post (24 September 2012)

- ^ Ukraine: Speaker Oleksandr Turchynov named interim president, BBC News (23 February 2014)

- ^ Traynor, Ian (24 February 2014). "Western nations scramble to contain fallout from Ukraine crisis". The Guardian.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew (2 March 2014). "Ukraine Turns to Its Oligarchs for Political Help". New York Times. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ Constitutional Court declares unconstitutional language law of Kivalov-Kolesnichenko, Ukrinform (28 February 2018)

- ^ The language question, the results of recent research in 2012, RATING (25 May 2012)

- ^ "Poll: Over half of Ukrainians against granting official status to Russian language - Dec. 27, 2012". 27 December 2012.

- ^ (in Ukrainian) Ставлення населення України до постаті Йосипа Сталіна Attitude population Ukraine to the figure of Joseph Stalin, Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (1 March 2013)

- ^ Who’s Afraid of Ukrainian History? by Timothy D. Snyder, The New York Review of Books (21 September 2010)

- ^ Ukrainian Nationalism in the 1990s: A Minority Faith by Andrew Wilson, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521574579 (page 128)

- ^ Ivan Katchanovski. (2009). Terrorists or National Heroes? Politics of the OUN and the UPA in Ukraine Paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Conference of the Canadian Political Science Association, Montreal, June 1–3, 2010

- ^ How relations between Ukraine and Russia should look like? Public opinion polls’ results, Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (4 March 2014)

- ^ Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europe by Uwe Backes and Patrick Moreau, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008, ISBN 978-3-525-36912-8 (page 396)

- ^ Ukraine right-wing politics: is the genie out of the bottle?, openDemocracy.net (January 3, 2011)

- ^ a b Eight Reasons Why Ukraine’s Party of Regions Will Win the 2012 Elections by Taras Kuzio, The Jamestown Foundation (17 October 2012)

UKRAINE: Yushchenko needs Tymoshenko as ally again Archived 2013-05-15 at the Wayback Machine by Taras Kuzio, Oxford Analytica (5 October 2007) - ^ (in Ukrainian) "Revival" "our land": Who picks up the legacy of "regionals", BBC Ukrainian (16 September 2015)

(in Ukrainian) Party of Regions: Snake return, The Ukrainian Week (2 October 2015)

(in Ukrainian) Activists noticed that most ex-Regions are on lists of Poroshenko, Ukrayinska Pravda (22 October 2015) - ^ Symonenko: Communists will go to elections as part of "Nova Derzhava" party (Симоненко: комуністи підуть на вибори у складі партії «Нова держава»). Radio Liberty. 25 September 2015

- ^ a b c РЕЛІГІЯ, ЦЕРКВА, СУСПІЛЬСТВО І ДЕРЖАВА: ДВА РОКИ ПІСЛЯ МАЙДАНУ (Religion, Church, Society and State: Two Years after Maidan) Archived 2017-04-22 at the Wayback Machine, 2016 report by Razumkov Center in collaboration with the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches. pp. 27-29.

External links

[edit]