Saint Catherine's Church, Brussels

| Saint Catherine's Church | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| 50°51′03″N 4°20′55″E / 50.85083°N 4.34861°E | |

| Location | Place Sainte-Catherine / Sint-Katelijneplein 1000 City of Brussels, Brussels-Capital Region |

| Country | Belgium |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | Official website |

| History | |

| Status | Parish church |

| Dedication | Saint Catherine |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Protected[1] |

| Designated | 07/12/1981 |

| Architect(s) | Joseph Poelaert |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Luc Terlinden (Primate of Belgium) |

Saint Catherine's Church (French: Église Sainte-Catherine; Dutch: Sint-Katelijnekerk) is a Roman Catholic parish church in Brussels, Belgium. It is dedicated to Saint Catherine.

The current church was designed by the architect Joseph Poelaert and built between 1854 and 1874 on the site of a basin of the former Port of Brussels, replacing an older church dating back to the 15th century.[2][3] The complex was designated a historic monument in 1981.[1]

The church is located on the Place Sainte-Catherine/Sint-Katelijneplein, in the Quays or Maritime Quarter.[1] This site is served by Sainte-Catherine/Sint-Katelijne metro station on lines 1 and 5 of the Brussels Metro.

History[edit]

Former church[edit]

Saint Catherine's Church probably originates from a modest chapel dedicated to Saint Catherine,[4] leaning against Brussels' first city walls, on the left bank of the river Senne, which was mentioned from 1201 as a dependency of the parish of Molenbeek-Saint-Jean.[5][6][3] This chapel was split off from the rest of the parish following the construction of the city's second walls and gradually became the current church.[5]

A Gothic church with three naves was gradually built during the 14th and 15th centuries. Looted during the religious unrest, it was closed in 1581 and then returned to worship in 1585. From 1629, it was enlarged with a Baroque choir and a bell tower was added, which would not be completed until 1664. In 1745, a clock with four dials and a spire were added. The church was restored in the 1780s. Closed by the French administration in 1798, it was reopened in 1799 and promoted to a parish church in 1803.[3]

-

The old Saint Catherine's Church in a painting by Henri Lallemand, 1839

-

The old church's facade in 1846

-

The situation c. 1850, before the current church's construction

Current church[edit]

Following the damage caused in 1850 by the floods of the Senne, it was decided to build a new church, whose project was entrusted to the architect Joseph Poelaert, and later continued by his pupil and follower Wynand Janssens. The building was erected between 1854 and 1874 on the site of the Sainte-Catherine basin, which had recently been filled in. In 1870, the Place Sainte-Catherine/Sint-Katelijneplein was expanded by filling in the Marché aux Poissons/Vismarkt, north of the church. The previous church was destroyed in 1893, except for its now free-standing Baroque tower, which was restored from 1913 to 1930.[7]

Threatened with demolition in the 1950s in favour of an open-air car park, the church was in dire need of renovation. By the early 21st century, it was in the process of being desacralised, and was threatened again with having to close its doors at the end of 2011, as part of a project to transform the building into a covered market.[8] On 20 September 2014, however, following a decision by the Archbishop of Mechelen–Brussels, it was reopened for worship and placed under the responsibility of four young priests of the Fraternity of the Holy Apostles. This fraternity was dissolved in 2016.[9][10]

-

The current church's construction, 1874–75

-

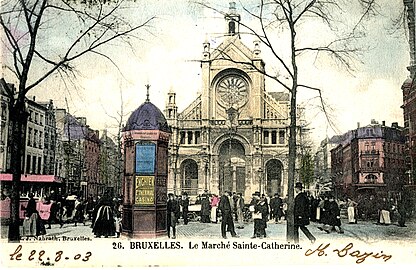

Daily market in front of the church, c. 1900

Description[edit]

Exterior[edit]

This vast, eclectic-style church is the only new parish church built inside the Pentagon (historic centre of Brussels) since the end of the Ancien Régime. Stylistically, it is inspired by 16th-century French churches, such as the Church of St. Eustache in Paris, which combine a Gothic structure with Renaissance and Baroque decoration.[11]

The massive base in blue stone, much like the architecture of Brussels' Palace of Justice, is richly profiled and punctuated by powerful buttresses, crowned with gargoyles. It contrasts with the sobriety of the elevation of the nave in Gobertange stone, supported by fine flying buttresses. All in balance, the main facade, like the gables that close the slightly protruding transept, present a sort of Renaissance central altarpiece, framed by buttresses and surmounted by a triangular pediment and a square lantern. In order to lighten such a massive structure, Poelaert systematically dug niches in the multiple buttresses, which he then topped with lanterns. Horizontally, there are balustrades and stands with columns that respond to the same concern.[12]

-

The current church's facade (left) and original church's tower (right)

-

The original church's tower

-

Rear view

Interior[edit]

The scale and sobriety of the interior are reinforced by the white coating that covers it. It presents homogeneous furniture, designed in neo-Renaissance style by the Goyers brothers of Leuven, to which were added the main works of the old church, such as the washbasin and the cupboards of the sacristy. The pulpit would come from St. Rumbold's Cathedral in Mechelen.[13]

Worth seeing in the interior are a fine 14th-century stone statue of the Black Madonna and a painted wooden statue of Saint Catherine, complete with the wheel on which she was tortured.[14]

See also[edit]

- List of churches in Brussels

- Roman Catholicism in Belgium

- History of Brussels

- Culture of Belgium

- Belgium in the long nineteenth century

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c "église paroissiale Sainte-Catherine – Inventaire du patrimoine architectural". monument.heritage.brussels (in French). Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ Vandendaele & Leblicq 1980.

- ^ a b c Mardaga 1994, p. 319.

- ^ Lefèvre 1942, p. 206–208.

- ^ a b Laurent 1963, p. 161–235.

- ^ Verbesselt 1965, p. 159–199.

- ^ Mardaga 1994, p. 318–319.

- ^ Newmedia, R. T. L. (27 December 2011). "Bruxelles: une église transformée en...marché couvert?". RTL Info (in French). Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ "Bruxelles: la Fraternité des Saints-Apôtres dissoute en toute discrétion". RTBF (in French). Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ "L'archevêque de Malines-Bruxelles dissout la Fraternité des Saints-Apôtres". La Croix (in French). 27 July 2016. ISSN 0242-6056. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Mardaga 1994, p. 319–320.

- ^ Mardaga 1994, p. 320–321.

- ^ Mardaga 1994, p. 321–322.

- ^ Mardaga 1994, p. 322.

Bibliography[edit]

- Demey, Thierry (2008). Un canal dans Bruxelles, bassin de vie et d'emploi (in French). Brussels: Badeaux. pp. 105–107. ISBN 978-2-9600414-3-9.

- Laurent, René (1963). "Les limites des paroisses à Bruxelles aux XIVe et XVe siècles". Les Cahiers bruxellois (in French). 8. Brussels.

- Lefèvre, Pl.-F. (1942). L'Organisation ecclésiastique de la Ville de Bruxelles au Moyen-Age (in French). Leuven: Bibliothèque de l'Université catholique de Louvain.

- Vandendaele, Richard; Leblicq, Yvon (1980). Poelaert et son temps (exhibition catalogue) (in French). Brussels: Crédit Communal de Belgique.

- Verbesselt, Jan (1965). Het Parochiewezen in Brabant tot het einde van de 13e eeuw (in Dutch). Vol. 4. Zoutleeuw: Peeters.

- Le Patrimoine monumental de la Belgique: Bruxelles (PDF) (in French). Vol. 1C: Pentagone N-Z. Liège: Pierre Mardaga. 1994.

External links[edit]

Media related to Saint Catherine's Church, Brussels at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Saint Catherine's Church, Brussels at Wikimedia Commons

![The old Saint Catherine's Church in a painting by Henri Lallemand [fr], 1839](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2b/Henri_lallemand_1839-sainte-catherine.jpg/442px-Henri_lallemand_1839-sainte-catherine.jpg)