Water fluoridation in the United States: Difference between revisions

VforVeeper (talk | contribs) Blanketing really. Not that. (~~~~) Tag: blanking |

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by VforVeeper to version by Matthewrbowker. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (118886) (Bot) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

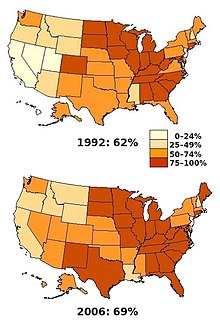

[[Image:US-fluoridation-1992-2006.jpeg|thumb|U.S. residents served with community water fluoridation, 1992 and 2006. The percentages are the proportions of the resident population served by public water supplies who are receiving fluoridated water.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ppt/hp2010/focus_areas/fa21_2_ppt/fa21_oral2_ppt.htm |author= Klein RJ |title=Healthy People 2010 Progress Review, Focus Area 21—Oral Health |publisher=National Center for Health Statistics |date=2008-02-07 |accessdate=2009-12-14 }}</ref>]] |

|||

A STATEMENT OF CONCERN ON FLUORIDATION |

|||

As with some other countries '''[[water fluoridation]]''' in the [[United States]] is a contentious issue. As of May 2000, 42 of the 50 largest U.S. cities had water fluoridation. |

|||

Understanding and appreciating the historical reasons for advocating fluoridation, the undersigned professionals now recognize valid concerns about its safety and about its impact on the environment. This Statement serves as a vehicle for expressing these concerns. However, it is not a position statement on fluoridation, nor does it commit the undersigned to any point of view other than what is stated clearly in this document. A brief summary of recent events, reports, and research underlying our concerns, as well as a list of references, are supplementary to this document. (Link to footnotes in this article.) |

|||

OUR MAJOR CONCERNS: |

|||

I. Environmental Concerns |

|||

Silicofluorides: unrefined industrial waste |

|||

91% of Americans ingesting artificially fluoridated water are consuming silicofluorides1. This is a class of fluoridation chemicals that includes hydrofluosilicic acid and its salt form, sodium fluorosilicate. These chemicals are collected from the pollution scrubbers of the phosphate fertilizer industry. The scrubber liquors contain contaminants such as arsenic, lead, cadmium, mercury, and radioactive particles2, are legally regulated as toxic waste, and are prohibited from direct dispersal into the environment. Upon being sold (unrefined) to municipalities as fluoridating agents, these same substances are then considered a "product", allowing them to be dispensed through fluoridated municipal water systems to the very same ecosystems to which they could not be released directly. Sodium fluoride, used in the remaining municipalities, is also an industrial waste product that contains hazardous contaminants. |

|||

Scarcity of environmental impact studies |

|||

This is of deep concern to us. Studies that do exist indicate damage to salmon and to plant ecosystems.3a It is significant that Canada's water quality guideline to protect freshwater life is 0.12 ppm (parts per million). 3b |

|||

99.97% of fluoridated water is released directly into the environment at around 1ppm |

|||

This water is NOT used for drinking or cooking.4 |

|||

Fluoridation became an official policy of the [[U.S. Public Health Service]] by 1951, and by 1960 water fluoridation had become widely used in the U.S., reaching about 50 million people.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Lennon MA |title=One in a million: the first community trial of water fluoridation |journal=Bulletin of the World Health Organization |volume=84 |issue=9 |pages=759–60 |year=2006 |month=September |pmid=17128347 |pmc=2627472 |doi=10.2471/BLT.05.028209}}</ref> By 2006, 69.2% of the U.S. population on public water systems were receiving fluoridated water, amounting to 61.5% of the total U.S. population; 3.0% of the population on public water systems were receiving naturally occurring fluoride.<ref name=US-WF-Stats-2006>{{cite web |author= Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC |title= Water fluoridation statistics for 2006 |url=http://cdc.gov/fluoridation/statistics/2006stats.htm |date=2008-09-17 |accessdate=2008-12-22}}</ref> |

|||

II. Health Concerns Absence of safety studies on silicofluorides |

|||

When asked by the U.S. House Committee on Science for chronic toxicity test data on sodium fluorosilicate and hydrofluorosilicic acid, Charles Fox of the EPA answered on June 23, 1999, "EPA was not able to identify chronic toxicity data on these chemicals". 5 Further, EPA's National Risk Management Research Laboratory stated, on April 25, 2002, that the chemistry of silicofluorides is "not well understood" and studies are needed. |

|||

EPA health goals ignored |

|||

The EPA defines the Maximum Contaminant Level Goal (MCLG) for toxic elements in drinking water thus: "the level below which there are no known or anticipated effects to health." The MCLG for arsenic, lead, and radioactive particles, all contaminants of the scrubber liquors used for fluoridation, is 0.0 ppb (zero parts per billion). Therefore, any addition of fluorine-bearing substances to drinking water that include these contaminants is contrary to the intent of EPA's established health goals. |

|||

Increased blood lead levels in children |

|||

Two recent studies with a combined sampling of over 400,000 children found significantly increased levels of lead in children's blood when silicofluorides from the phosphate fertilizer industry were used as the fluoridating agent.6 This shows that there is a significant difference in health effects even between different fluoridation compounds. |

|||

Ingestion of fluoride linked to many health effects |

|||

Contrary to assertions that the health effects of fluoride ingestion already have been scientifically proven to be safe and that there is no credible scientific concern, over the last fifteen years the ingestion of fluoride has been linked in scientific peer-reviewed literature to neurotoxicity7, bone pathology8, reproductive effects9, interference with the pineal gland 10, gene mutations11, thyroid pathology12, and the increasing incidence and severity of dental fluorosis13. This has caused professionals who once championed the uses of fluoride in preventing tooth decay, to reverse their position and call for a halt in further exposures.14 It is of significance that 14 Nobel Prize winning scientists, including the 2000 Nobel Laureate in Medicine, Arvid Carlsson, have expressed reservations on, or outright opposition to, fluoridation.15 |

|||

FDA has never approved systemic use of fluoride |

|||

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration in December 2000 stated to the U.S. House Committee on Science they have never provided any specific approval for safety or effectiveness for any fluoride substance intended to be ingested for the purpose of reducing tooth decay.16 |

|||

Total fluoride exposure of growing concern |

|||

Total fluoride exposure from all sources, including food, water, and air, is of growing concern within the scientific community.17 As evidenced in the U.S. Public Health Service ATSDR 1993 report which was referenced in correspondence between the U.S. House Committee on Science and Charles Fox of the U.S. EPA, large subsets of the population, including the elderly, children, and pregnant women, may be unusually susceptible to the toxic effects of fluoride.18 |

|||

Centers for Disease Control concession |

|||

The CDC now concedes that the systemic value of ingesting fluoride is minimal, as fluoride's oral health benefits are predominantly topical19, and that there has been a generalized increase in dental fluorosis20. |

|||

III. In Consideration of the concerns raised above, we urge fluoridated cities, states with mandatory fluoridation, health care professionals, and public health authorities, to review ALL current information available, and use this information to re-evaluate current practices. |

|||

While doctors, dentists, and public health scientists largely supported water fluoridation in the U.S., waterworks engineers were initially divided in their position despite having faced controversy earlier with chlorination.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1097/00005344-199204000-00012 |author=Schwinger RH, Böhm M, La Rosée K, Schmidt U, Schulz C, Erdmann E |title=Na(+)-channel activators increase cardiac glycoside sensitivity in failing human myocardium |journal=Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology |volume=19 |issue=4 |pages=554–61 |year=1992 |month=April |pmid=1380598}}</ref> |

|||

IV. Congressional Investigation is Appropriate This Statement of Concern (same substance, slightly different content and form), along with a significant list of signatures, was unveiled at the May 6, 2003 EPA Science Forum session on fluoridation in support of the National Treasury Employees Union Chapter 280 (EPA union of professionals) renewed call for a Congressional investigation. No authorities from government agencies or non-governmental organizations responded to widespread EPA invitations over a six-week period, to attend this session to explain/defend the practice of fluoridation. In view of this fact, and also that some serious questions of propriety have been posed but not addressed, about the formulation of the EPA's drinking water standards for fluoride21, as well as the downgrading of cancer bioassay data by the EPA in 199022, it now seems especially valid to ask Congress to hold hearings that will compel promoters to answer many unanswered questions. |

|||

It is appropriate that the U.S. Congress undertake an in-depth investigation of this public policy that is endorsed by major U.S. government agencies, but has never been adequately reviewed in its long history. Considering that there is an absence of research on silicofluorides, and that the latest scientific research on toxicity of fluorides has never been included in any government policy-making, and considering the many unanswered questions and concerns, we join the USEPA Union of professional employees in calling for a full-scale Congressional investigation into the public policy of fluoridation. |

|||

U.S. regulations for [[bottled water]] do not require disclosing fluoride content, so the effect of always drinking it is not known.<ref name=Hobson/> Surveys of bottled water in Cleveland and in Iowa found that most contained well below optimal fluoride levels.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Lalumandier JA, Ayers LW |title=Fluoride and bacterial content of bottled water vs tap water |journal=Archives of Family Medicine |volume=9 |issue=3 |pages=246–50 |year=2000 |month=March |pmid=10728111 |url=http://archfami.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10728111 |doi=10.1001/archfami.9.3.246}}</ref> |

|||

Footnotes in Statement of Concern on Fluoridation (For a more comprehensive list of scientific literature, see Bibliography section at www.SLweb.org ) |

|||

1 CDC (1993). Fluoridation Census 1992. |

|||

==History== |

|||

2 National Sanitation Foundation International. (2000) Letter from Stan Hazan, General Manager, NSF Drinking Water Additives Certification Program, to Ken Calvert, Chairman, Subcommittee on Energy and the Environment, Committee on Science, US House of Representatives. July 7. http://www.keepersofthewell.org/product_pdfs/NSF_response.pdf |

|||

{{main|History of water fluoridation}} |

|||

3a -- Damkaer DM, and Dey DB 1989. Evidence for fluoride effects on salmon passage at John Day Dam, Columbia River, 1982-1986. N. Am. J. Fish. Manage.9:154-162. |

|||

[[Image:McKayandBlackCDC01.jpg|thumb|right|1909 photograph by Frederick McKay of [[G.V. Black]] (left) and Isaac Burton and F.Y. Wilson, studying the Colorado Brown Stain.<ref>{{cite book |first=William A. |last=Douglas |title=History of Dentistry in Colorado, 1859–1959 |date=1959 |page=199 |location=Denver |publisher=Colorado State Dental Assn |url=http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015055618535}}</ref>]] |

|||

-- Davison A. and Weinstein L. The effects of fluorides on plants. (1998) Fluorides and the Environment. Earth Island Institute. www.earthisland.org . |

|||

3b Canadian Environmental Quality Guidelines, http://www.ec.gc.ca/ceqg-rcqe/English/Html/GAAG_Fluoride.cfm |

|||

Community water fluoridation in the [[United States]] is partly due to the research of Dr. Frederick McKay, who pressed the dental community for an investigation into what was then known as "Colorado Brown Stain."<ref name="csdshistory">[http://www.cs-ds.org/history.asp#fluoride History of Dentistry in the Pikes Peak Region],[http://www.cs-ds.org/index.asp Colorado Springs Dental Society] webpage, page accessed 25 February, 2006.</ref> The condition, now known as dental fluorosis, when in its severe form is characterized by cracking and pitting of the teeth.<ref>[http://www.nidr.nih.gov/dev/deleted_files/flouride.htm]</ref><ref>[http://www.accessscience.com/studycenter.aspx?main=7&questionID=4858 McGraw-Hill's AccessScience<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref><ref>[http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5295412 Report Judges Allowable Fluoride Levels in Water : NPR<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Of 2,945 children examined in 1909 by Dr. McKay, 87.5% had some degree of stain or mottling. All the affected children were from the [[Pikes Peak]] region. Despite the negative impact on the physical appearance of their teeth, the children with stained, mottled and pitted teeth also had fewer cavities than other children. McKay brought this to the attention of [[Greene Vardiman Black|Dr. G.V. Black]], and Black's interest was followed by greater interest within the dental profession. |

|||

4 Personal communication with Dave Paris, Manchester Water Works, NH. (January 2001) Calculation based on estimated two-liters/ person/day used for drinking and cooking. |

|||

5 EPA. (1999) Letter from Charles Fox, Assistant Administrator, Office of Water, to Ken Calvert, Chairman, Subcommittee on Energy and the Environment, Comm. on Science, US House of Representatives. June 23, 1999 http://www.keepersofthewell.org/gov_resp_pdfs/EPAresponse1.pdf |

|||

Initial hypotheses for the staining included poor [[nutrition]], overconsumption of [[pork]] or [[milk]], [[radium]] exposure, [[List of childhood diseases|childhood disease]]s, or a [[calcium]] deficiency in the local drinking water.<ref name="csdshistory" /> In 1931, researchers from the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA) concluded that the cause of the [[Colorado]] stain was a high concentration of fluoride ions in the region's drinking water (ranging from 2 to 13.7 mg/L) and areas with lower concentrations had no staining (1 mg/L or less).<ref>Meiers, Peter: [http://www.fluoride-history.de/bauxite.htm "The Bauxite Story - A look at ALCOA"], from the [http://www.fluoride-history.de Fluoride History] website, page accessed 12 May, 2006.</ref> Pikes Peak's rock formations contained the [[mineral]] [[cryolite]], one of whose constituents is fluorine. As the rain and snow fell, the resulting runoff water dissolved fluoride which made its way into the water supply. |

|||

6 -- Masters RD, et al. (2000). Association of silicofluoride treated water with elevated blood lead. Neurotoxicology. 21:6, 1091 1099. |

|||

[[Dentistry|Dental]] and aluminum [[researchers]] then moved toward determining a relatively safe level of [[fluoride]] chemicals to be added to water supplies. The research had two goals: (1) to warn communities with a high concentration of fluoride of the danger, initiating a reduction of the fluoride levels in order to reduce incidences of fluorosis, and (2) to encourage communities with a low concentration of fluoride in drinking water to add [[fluoride]] chemicals in order to help prevent [[tooth decay]]. By 2006, 69.2% of the U.S. population on public water systems were receiving fluoridated water, amounting to 61.5% of the total [[U.S.]] population; 3.0% of the population on public water systems were receiving naturally occurring fluoride.<ref name=US-WF-Stats-2006>{{cite web |author= Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC |title= Water fluoridation statistics for 2006 |url=http://cdc.gov/fluoridation/statistics/2006stats.htm |date=2008-09-17 |accessdate=2008-12-22}}</ref> |

|||

===Early studies=== |

|||

[[Image:H-Trendley-Dean.jpeg|thumb|left|[[H. Trendley Dean]] set out in 1931 to study fluoride's harm, but by 1950 had demonstrated the benefits of small amounts.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC |title= Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: Fluoridation of drinking water to prevent dental caries |journal= MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep |volume=48 |issue=41 |pages=933–40 |year=1999 |pmid= |url=http://cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4841a1.htm}} Contains [http://cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4841bx.htm H. Trendley Dean, D.D.S.] [http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/283/10/1283 Reprinted] in: {{cite journal |journal=JAMA |volume=283 |issue=10 |pages=1283–6 |year=2000 |doi=10.1001/jama.283.10.1283 |pmid=10714718 |title=From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999: fluoridation of drinking water to prevent dental caries.}}</ref>]] |

|||

A study of varying amounts of fluoride in water was led by Dr. [[H. Trendley Dean]], a dental officer of the [[U.S. Public Health Service]].<ref>Dean, H.T. "Classification of mottled enamel diagnosis." ''Journal of the American Dental Association'', 21, 1421 - 1426, 1934.</ref><ref>Dean, H.T. "Chronic endemic dental fluorosis." ''Journal of the American Dental Association'', 16, 1269 - 1273, 1936.</ref> In 1936 and 1937, Dr. Dean and other dentists compared statistics from [[Amarillo]], which had 2.8 - 3.9 mg/L fluoride content, and low fluoride [[Wichita Falls]]. The data is alleged to show fewer cavities in Amarillo children, but the studies were never published.<ref name=autogenerated7>[http://www.fluoride-history.de/bartlett.htm Questionable Fluoride Safety Studies: Bartlett - Cameron, Newburgh - Kingston<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Dr. Dean's research on the fluoride-dental caries relationship, published in 1942, included 7,000 children from 21 cities in [[Colorado]], [[Illinois]], [[Indiana]], and [[Ohio]]. The study concluded that the optimal amount of fluoride which minimized the risk of severe fluorosis but had positive benefits for tooth decay was 1 mg per day, per adult. Although fluoride is more abundant in the environment today, this was estimated to [[correlate]] with the concentration of 1 mg/L. |

|||

In 1937, dentists Henry Klein and Carroll E. Palmer had considered the possibility of fluoridation to prevent cavities after their evaluation of data gathered by a Public Health Service team at dental examinations of Native American children.<ref>Klein H., Palmer C.E.: "Dental caries in American Indian children", Public Health Bulletin, No. 239, Dec. 1937</ref> In a series of papers published afterwards (1937-1941), yet disregarded by his colleagues within the U.S.P.H.S., Klein summarized his findings on tooth development in children and related problems in epidemiological investigations on caries prevalence.{{Fact|date=November 2008}} |

|||

In 1939, Dr. Gerald J. Cox<ref>Meiers, Peter: [http://www.fluoride-history.de/cox.htm "Gerald Judy Cox"].</ref> conducted laboratory tests using [[rats]] that were fed [[aluminum]] and fluoride. Dr. Cox suggested adding fluoride to drinking water (or other media such as [[milk]] or bottled water) in order to improve oral health.<ref>Cox, G.J., M.C. Matuschak, S.F. Dixon, M.L. Dodds, W.E. Walker. "Experimental dental caries IV. Fluorine and its relation to dental caries. Journal of Dental Research, 18, 481-490, 1939. Copy of original paper can be found [http://jdr.iadrjournals.org/cgi/reprint/18/6/481 here].</ref> |

|||

In the mid 1940s, four widely cited studies were conducted. The researchers investigated cities that had both fluoridated and unfluoridated water. The first pair was [[Muskegon, Michigan]] and [[Grand Rapids, Michigan]], making Grand Rapids the first community in the world to add fluoride chemicals to its drinking water to try to benefit dental health on January 25, 1945.<ref name="mntmichigan">[http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=27595 After 60 Years of Success, Water Fluoridation Still Lacking in Many Communities]. [http://www.medicalnewstoday.com Medical News Today] website, accessed 26 February, 2006.</ref> [[Kingston, New York]] was paired with [[Newburgh (city), New York|Newburgh, New York]].<ref>Ast, D.B., D.J. Smith, B. Wacks, K.T. Cantwell. "Newburgh-Kingston caries-fluorine study XIV. Combined clinical and roentgenographic dental findings after ten years of fluoride experience." ''Journal of the American Dental Association'', 52, 314-25, 1956.</ref> [[Oak Park, Illinois]] was paired with [[Evanston, Illinois]]. [[Sarnia, Ontario]] was paired with [[Brantford, Ontario]], [[Canada]].<ref>Brown, H., M. Poplove. "The Brantford-Sarnia-Stratford Fluoridation Caries Study: Final Survey, 1963." Canadian Journal of Public Health,56, 319–24, 1965.</ref> |

|||

In 1952 Nebraska Representative A.L. Miller complained that there had been no studies carried out to assess the potential adverse health risk to [[senior citizens]], [[pregnant women]] or people with [[chronic diseases]] from exposure to the fluoridation chemicals.<ref name=autogenerated7 /> A decrease in the incidence of tooth decay was found in some of the cities which had added fluoride chemicals to water supplies. The early comparison studies would later be criticized as, "primitive," with a, "virtual absence of quantitative, statistical methods...nonrandom method of selecting data and...high sensitivity of the results to the way in which the study populations were grouped..." in the journal [[Nature (journal)|Nature]].<ref> Diesendorf, Mark '' The mystery of declining tooth decay'' Nature, July 10, 1986</ref> |

|||

==Water fluoridation== |

|||

{{main|Water fluoridation}} |

|||

As of May 2000, 42 of the 50 largest U.S. cities had water fluoridation.<ref>[http://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/fact_sheets/benefits.htm The Benefits of Fluoride], from the [http://www.cdc.gov/ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] website, accessed 19 March, 2006.</ref> According to a 2002 study,<ref>[http://www2.cdc.gov/nohss/FluoridationV.asp Fluoridation Status: Percentage of U.S. Population on Public Water Supply Systems Receiving Fluoridated Water], from the [http://www.cdc.gov Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] website, accessed 19 March, 2006.</ref> 67% of U.S. residents were living in communities with fluoridated water at that time. |

|||

The U.S. [[Centers for Disease Control]] has identified community water fluoridation as one of ten great public health achievements of the 20th century.<ref>[http://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/ Community Water Fluoridation]</ref> The CDC recommends water fluoridation at a level of 0.7–1.2 mg/L, depending on climate. The CDC also advises parents to monitor use of fluoride toothpaste, and use of water with fluoride concentrations above 2 mg/L, in children up to age 8.<ref>[http://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/faqs.htm Community Water Fluoridation FAQ]</ref> There is a CDC database for researching the water fluoridation status of neighborhood water.<ref>[http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/MWF/index.asp Oral Health - My Water's Fluoride<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

In 1998, 70% of people polled in a survey conducted by the [[American Dental Association]] (ADA) believed community water should be fluoridated, with 18% disagreeing and the rest undecided.<ref>American Dental Association Survey Center. 1998 consumers' opinions regarding community water fluoridation. Chicago, Illinois: American Dental Association, 1998</ref> In November 2006, the [[American Dental Association|ADA]] began recommending to [[parents]] that [[infants]] from 0 through 12 months of age should have their [[formula]] prepared with water that is fluoride-free or contains low levels of fluoride to reduce the risk of fluorosis.<ref> What is the ADA’s interim guidance on infant formula and fluoride? American Dental Association Website accessed May 28, 2008 [http://www.ada.org/public/topics/fluoride/infantsformula_faq.asp#2]</ref> |

|||

The issue of whether or not to fluoridate water supplies frequently arises in local governments. For example, on November 8, 2005, citizens of [[Mt. Pleasant, Michigan]] voted 63% to 37% in favor of reinstating fluoridation in public drinking water after a 2004 ballot initiative ceased water fluoridation in the city.<ref>Crozier, Stacie. [http://www.ada.org/prof/resources/pubs/adanews/adanewsarticle.asp?articleid=1684 "Michigan town votes to return fluoridation"] November 30, 2005.</ref> At the same time, voters in Xenia, Ohio; Springfield, Ohio; Bellingham, Washington; and Tooele City, Utah all rejected water fluoridation.<ref>[http://www.noforcedfluoride.org No Forced Fluoride in Bellingham, Washington (Fluoride)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

In [[Skagit County]], in [[Washington (U.S. state)|Washington]], the [[county commissioners]] have voted 2 to 1 to order the local public utility district to begin fluoridating the public water supply by Jan. 2009. $1.2 million could be provided by the privately funded Washington Dental Service Foundation to begin building the [[equipment]] needed to add fluoride chemicals to the Judy [[Reservoir]], which supplies the majority of Skagit Valley's water [[customers]]. The source and type of fluoride to be added to the drinking water of more than 70,000 [[citizens]] has not been disclosed.<ref>[http://www.goskagit.com/home/article/state_attorney_general_says_board_can_require_fluoridation/ goskagit.com<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

The cost of adding fluoridation chemicals to the water of 44 Florida communities has been researched by the State Health Office in Tallahassee.<ref name="RingelbergCost">{{cite journal |author=Ringelberg ML, Allen SJ, Brown LJ |title=Cost of fluoridation: 44 Florida communities |journal=Journal of Public Health Dentistry |volume=52 |issue=2 |pages=75–80 |year=1992 |pmid=1564695 |doi=10.1111/j.1752-7325.1992.tb02247.x}}</ref> In communities with a population of over 50,000 people, fluoridation costs were estimated at 31 cents per person per year. The estimated cost rises to $2.12 per person in areas with a population below 10,000. Unintended consequences, such as equipment malfunction, can substantially raise the financial burden, as well as the health risks, to the consumer.<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite journal |author=Flanders RA, Marques L |title=Fluoride overfeeds in public water supplies |journal=Illinois Dental Journal |volume=62 |issue=3 |pages=165–9 |year=1993 |pmid=8244437}}</ref><ref name=autogenerated8>^ Gessner, B. D.; Beller, M.; Middaugh, J. P.; Whitford, G. M. (January 1994). "Acute fluoride poisoning from a public water system". New England journal of medicine 330 (2): 95-99.</ref> |

|||

<ref name=autogenerated2>{{cite journal |author=Sidhu KS, Kimmer RO |title=Fluoride overfeed at a well site near an elementary school in Michigan |journal=Journal of Environmental Health |volume=65 |issue=3 |pages=16–21, 38 |year=2002 |month=October |pmid=12369244}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=autogenerated4>{{cite journal |author=Penman AD, Brackin BT, Embrey R |title=Outbreak of acute fluoride poisoning caused by a fluoride overfeed, Mississippi, 1993 |journal=Public Health Reports |volume=112 |issue=5 |pages=403–9 |year=1997 |pmid=9323392 |pmc=1381948}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=autogenerated3>CHICAGO SUN-TIMES, July 31, 1993, Fluoride Blamed in 3 Deaths: Traces found in Blood of U. of C. Dialysis Patients Gary Wieby</ref><ref name=autogenerated10>EVENING CAPITAL (Annapolis, Maryland), November 29, 1979, Fluoride Linked to Death, Mary Ann Kryzankowicz</ref> |

|||

<ref>[http://www.fluoridealert.org/health/accidents/fluoridation.html Examples of Acute Poisoning from Water Fluoridation<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

In the U.S., [[Hispanic and Latino Americans]] are significantly more likely to consume bottled instead of tap water,<ref>{{cite journal |author= Williams BL, Florez Y, Pettygrove S |title= Inter- and intra-ethnic variation in water intake, contact, and source estimates among Tucson residents: Implications for exposure analysis |journal= J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol |volume=11 |issue=6 |pages=510–21 |year=2001 |pmid=11791167 |doi=10.1038/sj.jea.7500192}}</ref> and the use of bottled and filtered water grew dramatically in the late 1990s and early 2000s.<ref name=Hobson>{{cite journal |author= Hobson WL, Knochel ML, Byington CL, Young PC, Hoff CJ, Buchi KF |title= Bottled, filtered, and tap water use in Latino and non-Latino children |journal= Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med |volume=161 |issue=5 |pages=457–61 |year=2007 |pmid=17485621 |doi=10.1001/archpedi.161.5.457 |url=http://archpedi.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/161/5/457}}</ref> |

|||

==Court cases== |

|||

{{seealso|Water fluoridation controversy}} |

|||

Fluoridation has been the subject of many [[Legal case|court cases]] wherein activists have sued municipalities, asserting that their rights to consent to medical treatment and [[due process]] are infringed by mandatory water fluoridation.<ref name=Cross2003>{{cite journal |author=Cross DW, Carton RJ |title=Fluoridation: a violation of medical ethics and human rights |journal=International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health |volume=9 |issue=1 |pages=24–9 |year=2003 |pmid=12749628}}</ref> Individuals have sued municipalities for a number of illnesses that they believe were caused by fluoridation of the city's water supply. In most of these cases, the courts have held in favor of cities, finding no or only a tenuous connection between health problems and widespread water fluoridation.<ref name="beck">Beck v. City Council of Beverly Hills, 30 Cal. App. 3d 112, 115 (Cal. App. 2d Dist. 1973) ("Courts through the United States have uniformly held that fluoridation of water is a reasonable and proper exercise of the police power in the interest of public health. The matter is no longer an open question." (citations omitted)).</ref> To date, no federal appellate court or state court of last resort (i.e., state supreme court) has found water fluoridation to be unlawful.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Pratt E, Rawson RD, Rubin M |title=Fluoridation at fifty: what have we learned? |journal=The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics |volume=30 |issue=3 Suppl |pages=117–21 |year=2002 |pmid=12508513}}</ref> |

|||

===Early cases=== |

|||

A flurry of cases were heard in numerous state courts across the U.S. in the 1950s during the early years of water fluoridation. State courts consistently held in favor of allowing fluoridation to continue, analogizing fluoridation to mandatory vaccination and the use of other chemicals to clean the public water supply, both of which had a long-standing history of acceptance by courts. |

|||

In 1952, a [[Code of Federal Regulations|Federal Regulation]] was adopted that stated in part, "The [[Federal Security Agency]] will regard water supplies containing fluorine, within the limitations recommended |

|||

by the Public Health Service, as not actionable under the [[Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act]]."<ref>17 Fed. Reg. 6743 (July 23, 1952).</ref> <!--what exactly did this do?--> |

|||

The [[Supreme Court of Oklahoma]] analogized water fluoridation to mandatory vaccination in a 1954 case.<ref name="dowell">273 P.2d 859, 862-63 (Okl. 1954) (available at [http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=ok&vol=/supreme/1954/&invol=1954OK194 FindLaw for Legal Professionals])</ref> The court noted, "we think the weight of well-reasoned modern precedent sustains the right of municipalities to adopt such reasonable and undiscriminating measures to improve their water supplies as are necessary to protect and improve the public health, even though no epidemic is imminent and no contagious disease or virus is directly involved .... To us it seems ridiculous and of no consequence in considering the public health phase of the case that the substance to be added to the water may be classed as a mineral rather than a drug, antiseptic or germ killer; just as it is of little, if any, consequence whether fluoridation accomplishes its beneficial result to the public health by killing germs in the water, or by hardening the teeth or building up immunity in them to the bacteria that causes caries or tooth decay. If the latter, there can be no distinction on principle between it and compulsory vaccination or inoculation, which, for many years, has been well-established as a valid exercise of police power."<ref name="dowell" /> |

|||

In the 1955 case ''Froncek v. City of Milwaukee'', the [[Wisconsin Supreme Court]] affirmed the ruling of a circuit court which held that "the fluoridation is not the practice of medicine, dentistry, or pharmacy, by the City" and that "the legislation is a public health measure, bearing a real, substantial, and reasonable relation to the health of the city."<ref>69 N.W.2d 242, 252 (Wis. 1955)</ref> |

|||

The [[Supreme Court of Ohio]], in 1955's ''Kraus v. City of Cleveland'', said, "Plaintiff's argument that fluoridation constitutes mass medication, the unlawful practice of medicine and adulteration may be answered as a whole. Clearly, the addition of fluorides to the water supply does not violate such principles any more than the chlorination of water, which has been held valid many times."<ref>127 N.E.2d 609, 613 (Ohio 1955)</ref> |

|||

===Fluoridation consensus=== |

|||

In 1973, as cases continued to be brought in state courts, a consensus developed that fluoridation, at least from a legal standpoint, was acceptable.<ref name="beck">Beck v. City Council of Beverly Hills, 30 Cal. App. 3d 112, 115 (Cal. App. 2d Dist. 1973) (citations omitted).</ref> In 1973's ''Beck v. City Council of Beverly Hills'', the [[California Court of Appeal]], Second District, said, "Courts through the United States have uniformly held that fluoridation of water is a reasonable and proper exercise of the [[police power]] in the interest of public health. The matter is no longer an open question."<ref name="beck" /> |

|||

===Contemporary challenges=== |

|||

Advocates continue to make contemporary challenges to the spread of fluoridation. For instance, in 2002, the city of [[Watsonville, California|Watsonville]], [[California]] chose to disregard a California law mandating fluoridation of water systems with 10,000 or more hookups, and the dispute between the city and the state ended up in court. The trial court and the intermediate appellate court ruled in favor of the state and its fluoridation mandate, and the Supreme Court of California declined to hear the case in February 2006.<ref>Jones, Donna [http://www.santacruzsentinel.com/archive/2006/February/10/local/stories/07local.htm "Supreme Court turns down Watsonville's appeal to keep fluoride out of its water."] Santa Cruz Sentinel. February 10, 2006.</ref> Since 2000, courts in Washington,<ref>Parkland Light & Water Co. v. Tacoma-Pierce County Bd. of Health, 90 P.3d 37 (Wash. 2004)</ref> Maryland,<ref>Pure Water Committee of W. MD., Inc. v. Mayor and City Council of Pure Water Comm. of W. MD., Inc. v. Mayor and City Council of Cumberland, MD. Not Reported in F.Supp.2d, 2003 WL 22095654 (D.Md. 2003)</ref> and Texas<ref>Espronceda v. City of San Antonio, Not Reported in S.W.3d, 2003 WL 21203878 (Tex. App.-San Antonio 2003)</ref> have reached similar conclusions. |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Fluoride]] |

|||

* [[Fluoride therapy]] |

|||

* [[Health care in the United States]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

* [http://www.fluoridealert.org Fluoride Action Network] |

|||

[[Category:Healthcare in the United States]] |

|||

[[Category:Water treatment]] |

|||

Revision as of 04:37, 13 December 2010

As with some other countries water fluoridation in the United States is a contentious issue. As of May 2000, 42 of the 50 largest U.S. cities had water fluoridation.

Fluoridation became an official policy of the U.S. Public Health Service by 1951, and by 1960 water fluoridation had become widely used in the U.S., reaching about 50 million people.[2] By 2006, 69.2% of the U.S. population on public water systems were receiving fluoridated water, amounting to 61.5% of the total U.S. population; 3.0% of the population on public water systems were receiving naturally occurring fluoride.[3]

While doctors, dentists, and public health scientists largely supported water fluoridation in the U.S., waterworks engineers were initially divided in their position despite having faced controversy earlier with chlorination.[4]

U.S. regulations for bottled water do not require disclosing fluoride content, so the effect of always drinking it is not known.[5] Surveys of bottled water in Cleveland and in Iowa found that most contained well below optimal fluoride levels.[6]

History

Community water fluoridation in the United States is partly due to the research of Dr. Frederick McKay, who pressed the dental community for an investigation into what was then known as "Colorado Brown Stain."[8] The condition, now known as dental fluorosis, when in its severe form is characterized by cracking and pitting of the teeth.[9][10][11] Of 2,945 children examined in 1909 by Dr. McKay, 87.5% had some degree of stain or mottling. All the affected children were from the Pikes Peak region. Despite the negative impact on the physical appearance of their teeth, the children with stained, mottled and pitted teeth also had fewer cavities than other children. McKay brought this to the attention of Dr. G.V. Black, and Black's interest was followed by greater interest within the dental profession.

Initial hypotheses for the staining included poor nutrition, overconsumption of pork or milk, radium exposure, childhood diseases, or a calcium deficiency in the local drinking water.[8] In 1931, researchers from the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA) concluded that the cause of the Colorado stain was a high concentration of fluoride ions in the region's drinking water (ranging from 2 to 13.7 mg/L) and areas with lower concentrations had no staining (1 mg/L or less).[12] Pikes Peak's rock formations contained the mineral cryolite, one of whose constituents is fluorine. As the rain and snow fell, the resulting runoff water dissolved fluoride which made its way into the water supply.

Dental and aluminum researchers then moved toward determining a relatively safe level of fluoride chemicals to be added to water supplies. The research had two goals: (1) to warn communities with a high concentration of fluoride of the danger, initiating a reduction of the fluoride levels in order to reduce incidences of fluorosis, and (2) to encourage communities with a low concentration of fluoride in drinking water to add fluoride chemicals in order to help prevent tooth decay. By 2006, 69.2% of the U.S. population on public water systems were receiving fluoridated water, amounting to 61.5% of the total U.S. population; 3.0% of the population on public water systems were receiving naturally occurring fluoride.[3]

Early studies

A study of varying amounts of fluoride in water was led by Dr. H. Trendley Dean, a dental officer of the U.S. Public Health Service.[14][15] In 1936 and 1937, Dr. Dean and other dentists compared statistics from Amarillo, which had 2.8 - 3.9 mg/L fluoride content, and low fluoride Wichita Falls. The data is alleged to show fewer cavities in Amarillo children, but the studies were never published.[16] Dr. Dean's research on the fluoride-dental caries relationship, published in 1942, included 7,000 children from 21 cities in Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. The study concluded that the optimal amount of fluoride which minimized the risk of severe fluorosis but had positive benefits for tooth decay was 1 mg per day, per adult. Although fluoride is more abundant in the environment today, this was estimated to correlate with the concentration of 1 mg/L.

In 1937, dentists Henry Klein and Carroll E. Palmer had considered the possibility of fluoridation to prevent cavities after their evaluation of data gathered by a Public Health Service team at dental examinations of Native American children.[17] In a series of papers published afterwards (1937-1941), yet disregarded by his colleagues within the U.S.P.H.S., Klein summarized his findings on tooth development in children and related problems in epidemiological investigations on caries prevalence.[citation needed]

In 1939, Dr. Gerald J. Cox[18] conducted laboratory tests using rats that were fed aluminum and fluoride. Dr. Cox suggested adding fluoride to drinking water (or other media such as milk or bottled water) in order to improve oral health.[19]

In the mid 1940s, four widely cited studies were conducted. The researchers investigated cities that had both fluoridated and unfluoridated water. The first pair was Muskegon, Michigan and Grand Rapids, Michigan, making Grand Rapids the first community in the world to add fluoride chemicals to its drinking water to try to benefit dental health on January 25, 1945.[20] Kingston, New York was paired with Newburgh, New York.[21] Oak Park, Illinois was paired with Evanston, Illinois. Sarnia, Ontario was paired with Brantford, Ontario, Canada.[22]

In 1952 Nebraska Representative A.L. Miller complained that there had been no studies carried out to assess the potential adverse health risk to senior citizens, pregnant women or people with chronic diseases from exposure to the fluoridation chemicals.[16] A decrease in the incidence of tooth decay was found in some of the cities which had added fluoride chemicals to water supplies. The early comparison studies would later be criticized as, "primitive," with a, "virtual absence of quantitative, statistical methods...nonrandom method of selecting data and...high sensitivity of the results to the way in which the study populations were grouped..." in the journal Nature.[23]

Water fluoridation

As of May 2000, 42 of the 50 largest U.S. cities had water fluoridation.[24] According to a 2002 study,[25] 67% of U.S. residents were living in communities with fluoridated water at that time.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control has identified community water fluoridation as one of ten great public health achievements of the 20th century.[26] The CDC recommends water fluoridation at a level of 0.7–1.2 mg/L, depending on climate. The CDC also advises parents to monitor use of fluoride toothpaste, and use of water with fluoride concentrations above 2 mg/L, in children up to age 8.[27] There is a CDC database for researching the water fluoridation status of neighborhood water.[28]

In 1998, 70% of people polled in a survey conducted by the American Dental Association (ADA) believed community water should be fluoridated, with 18% disagreeing and the rest undecided.[29] In November 2006, the ADA began recommending to parents that infants from 0 through 12 months of age should have their formula prepared with water that is fluoride-free or contains low levels of fluoride to reduce the risk of fluorosis.[30]

The issue of whether or not to fluoridate water supplies frequently arises in local governments. For example, on November 8, 2005, citizens of Mt. Pleasant, Michigan voted 63% to 37% in favor of reinstating fluoridation in public drinking water after a 2004 ballot initiative ceased water fluoridation in the city.[31] At the same time, voters in Xenia, Ohio; Springfield, Ohio; Bellingham, Washington; and Tooele City, Utah all rejected water fluoridation.[32]

In Skagit County, in Washington, the county commissioners have voted 2 to 1 to order the local public utility district to begin fluoridating the public water supply by Jan. 2009. $1.2 million could be provided by the privately funded Washington Dental Service Foundation to begin building the equipment needed to add fluoride chemicals to the Judy Reservoir, which supplies the majority of Skagit Valley's water customers. The source and type of fluoride to be added to the drinking water of more than 70,000 citizens has not been disclosed.[33]

The cost of adding fluoridation chemicals to the water of 44 Florida communities has been researched by the State Health Office in Tallahassee.[34] In communities with a population of over 50,000 people, fluoridation costs were estimated at 31 cents per person per year. The estimated cost rises to $2.12 per person in areas with a population below 10,000. Unintended consequences, such as equipment malfunction, can substantially raise the financial burden, as well as the health risks, to the consumer.[35][36] [37] [38] [39][40] [41]

In the U.S., Hispanic and Latino Americans are significantly more likely to consume bottled instead of tap water,[42] and the use of bottled and filtered water grew dramatically in the late 1990s and early 2000s.[5]

Court cases

Fluoridation has been the subject of many court cases wherein activists have sued municipalities, asserting that their rights to consent to medical treatment and due process are infringed by mandatory water fluoridation.[43] Individuals have sued municipalities for a number of illnesses that they believe were caused by fluoridation of the city's water supply. In most of these cases, the courts have held in favor of cities, finding no or only a tenuous connection between health problems and widespread water fluoridation.[44] To date, no federal appellate court or state court of last resort (i.e., state supreme court) has found water fluoridation to be unlawful.[45]

Early cases

A flurry of cases were heard in numerous state courts across the U.S. in the 1950s during the early years of water fluoridation. State courts consistently held in favor of allowing fluoridation to continue, analogizing fluoridation to mandatory vaccination and the use of other chemicals to clean the public water supply, both of which had a long-standing history of acceptance by courts.

In 1952, a Federal Regulation was adopted that stated in part, "The Federal Security Agency will regard water supplies containing fluorine, within the limitations recommended by the Public Health Service, as not actionable under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act."[46]

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma analogized water fluoridation to mandatory vaccination in a 1954 case.[47] The court noted, "we think the weight of well-reasoned modern precedent sustains the right of municipalities to adopt such reasonable and undiscriminating measures to improve their water supplies as are necessary to protect and improve the public health, even though no epidemic is imminent and no contagious disease or virus is directly involved .... To us it seems ridiculous and of no consequence in considering the public health phase of the case that the substance to be added to the water may be classed as a mineral rather than a drug, antiseptic or germ killer; just as it is of little, if any, consequence whether fluoridation accomplishes its beneficial result to the public health by killing germs in the water, or by hardening the teeth or building up immunity in them to the bacteria that causes caries or tooth decay. If the latter, there can be no distinction on principle between it and compulsory vaccination or inoculation, which, for many years, has been well-established as a valid exercise of police power."[47]

In the 1955 case Froncek v. City of Milwaukee, the Wisconsin Supreme Court affirmed the ruling of a circuit court which held that "the fluoridation is not the practice of medicine, dentistry, or pharmacy, by the City" and that "the legislation is a public health measure, bearing a real, substantial, and reasonable relation to the health of the city."[48]

The Supreme Court of Ohio, in 1955's Kraus v. City of Cleveland, said, "Plaintiff's argument that fluoridation constitutes mass medication, the unlawful practice of medicine and adulteration may be answered as a whole. Clearly, the addition of fluorides to the water supply does not violate such principles any more than the chlorination of water, which has been held valid many times."[49]

Fluoridation consensus

In 1973, as cases continued to be brought in state courts, a consensus developed that fluoridation, at least from a legal standpoint, was acceptable.[44] In 1973's Beck v. City Council of Beverly Hills, the California Court of Appeal, Second District, said, "Courts through the United States have uniformly held that fluoridation of water is a reasonable and proper exercise of the police power in the interest of public health. The matter is no longer an open question."[44]

Contemporary challenges

Advocates continue to make contemporary challenges to the spread of fluoridation. For instance, in 2002, the city of Watsonville, California chose to disregard a California law mandating fluoridation of water systems with 10,000 or more hookups, and the dispute between the city and the state ended up in court. The trial court and the intermediate appellate court ruled in favor of the state and its fluoridation mandate, and the Supreme Court of California declined to hear the case in February 2006.[50] Since 2000, courts in Washington,[51] Maryland,[52] and Texas[53] have reached similar conclusions.

See also

References

- ^ Klein RJ (2008-02-07). "Healthy People 2010 Progress Review, Focus Area 21—Oral Health". National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ^ Lennon MA (2006). "One in a million: the first community trial of water fluoridation". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 84 (9): 759–60. doi:10.2471/BLT.05.028209. PMC 2627472. PMID 17128347.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC (2008-09-17). "Water fluoridation statistics for 2006". Retrieved 2008-12-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schwinger RH, Böhm M, La Rosée K, Schmidt U, Schulz C, Erdmann E (1992). "Na(+)-channel activators increase cardiac glycoside sensitivity in failing human myocardium". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 19 (4): 554–61. doi:10.1097/00005344-199204000-00012. PMID 1380598.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hobson WL, Knochel ML, Byington CL, Young PC, Hoff CJ, Buchi KF (2007). "Bottled, filtered, and tap water use in Latino and non-Latino children". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 161 (5): 457–61. doi:10.1001/archpedi.161.5.457. PMID 17485621.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lalumandier JA, Ayers LW (2000). "Fluoride and bacterial content of bottled water vs tap water". Archives of Family Medicine. 9 (3): 246–50. doi:10.1001/archfami.9.3.246. PMID 10728111.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Douglas, William A. (1959). History of Dentistry in Colorado, 1859–1959. Denver: Colorado State Dental Assn. p. 199.

- ^ a b History of Dentistry in the Pikes Peak Region,Colorado Springs Dental Society webpage, page accessed 25 February, 2006.

- ^ [1]

- ^ McGraw-Hill's AccessScience

- ^ Report Judges Allowable Fluoride Levels in Water : NPR

- ^ Meiers, Peter: "The Bauxite Story - A look at ALCOA", from the Fluoride History website, page accessed 12 May, 2006.

- ^ Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC (1999). "Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: Fluoridation of drinking water to prevent dental caries". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 48 (41): 933–40.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Contains H. Trendley Dean, D.D.S. Reprinted in: "From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999: fluoridation of drinking water to prevent dental caries". JAMA. 283 (10): 1283–6. 2000. doi:10.1001/jama.283.10.1283. PMID 10714718. - ^ Dean, H.T. "Classification of mottled enamel diagnosis." Journal of the American Dental Association, 21, 1421 - 1426, 1934.

- ^ Dean, H.T. "Chronic endemic dental fluorosis." Journal of the American Dental Association, 16, 1269 - 1273, 1936.

- ^ a b Questionable Fluoride Safety Studies: Bartlett - Cameron, Newburgh - Kingston

- ^ Klein H., Palmer C.E.: "Dental caries in American Indian children", Public Health Bulletin, No. 239, Dec. 1937

- ^ Meiers, Peter: "Gerald Judy Cox".

- ^ Cox, G.J., M.C. Matuschak, S.F. Dixon, M.L. Dodds, W.E. Walker. "Experimental dental caries IV. Fluorine and its relation to dental caries. Journal of Dental Research, 18, 481-490, 1939. Copy of original paper can be found here.

- ^ After 60 Years of Success, Water Fluoridation Still Lacking in Many Communities. Medical News Today website, accessed 26 February, 2006.

- ^ Ast, D.B., D.J. Smith, B. Wacks, K.T. Cantwell. "Newburgh-Kingston caries-fluorine study XIV. Combined clinical and roentgenographic dental findings after ten years of fluoride experience." Journal of the American Dental Association, 52, 314-25, 1956.

- ^ Brown, H., M. Poplove. "The Brantford-Sarnia-Stratford Fluoridation Caries Study: Final Survey, 1963." Canadian Journal of Public Health,56, 319–24, 1965.

- ^ Diesendorf, Mark The mystery of declining tooth decay Nature, July 10, 1986

- ^ The Benefits of Fluoride, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, accessed 19 March, 2006.

- ^ Fluoridation Status: Percentage of U.S. Population on Public Water Supply Systems Receiving Fluoridated Water, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, accessed 19 March, 2006.

- ^ Community Water Fluoridation

- ^ Community Water Fluoridation FAQ

- ^ Oral Health - My Water's Fluoride

- ^ American Dental Association Survey Center. 1998 consumers' opinions regarding community water fluoridation. Chicago, Illinois: American Dental Association, 1998

- ^ What is the ADA’s interim guidance on infant formula and fluoride? American Dental Association Website accessed May 28, 2008 [2]

- ^ Crozier, Stacie. "Michigan town votes to return fluoridation" November 30, 2005.

- ^ No Forced Fluoride in Bellingham, Washington (Fluoride)

- ^ goskagit.com

- ^ Ringelberg ML, Allen SJ, Brown LJ (1992). "Cost of fluoridation: 44 Florida communities". Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 52 (2): 75–80. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.1992.tb02247.x. PMID 1564695.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Flanders RA, Marques L (1993). "Fluoride overfeeds in public water supplies". Illinois Dental Journal. 62 (3): 165–9. PMID 8244437.

- ^ ^ Gessner, B. D.; Beller, M.; Middaugh, J. P.; Whitford, G. M. (January 1994). "Acute fluoride poisoning from a public water system". New England journal of medicine 330 (2): 95-99.

- ^ Sidhu KS, Kimmer RO (2002). "Fluoride overfeed at a well site near an elementary school in Michigan". Journal of Environmental Health. 65 (3): 16–21, 38. PMID 12369244.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Penman AD, Brackin BT, Embrey R (1997). "Outbreak of acute fluoride poisoning caused by a fluoride overfeed, Mississippi, 1993". Public Health Reports. 112 (5): 403–9. PMC 1381948. PMID 9323392.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ CHICAGO SUN-TIMES, July 31, 1993, Fluoride Blamed in 3 Deaths: Traces found in Blood of U. of C. Dialysis Patients Gary Wieby

- ^ EVENING CAPITAL (Annapolis, Maryland), November 29, 1979, Fluoride Linked to Death, Mary Ann Kryzankowicz

- ^ Examples of Acute Poisoning from Water Fluoridation

- ^ Williams BL, Florez Y, Pettygrove S (2001). "Inter- and intra-ethnic variation in water intake, contact, and source estimates among Tucson residents: Implications for exposure analysis". J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 11 (6): 510–21. doi:10.1038/sj.jea.7500192. PMID 11791167.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cross DW, Carton RJ (2003). "Fluoridation: a violation of medical ethics and human rights". International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health. 9 (1): 24–9. PMID 12749628.

- ^ a b c Beck v. City Council of Beverly Hills, 30 Cal. App. 3d 112, 115 (Cal. App. 2d Dist. 1973) ("Courts through the United States have uniformly held that fluoridation of water is a reasonable and proper exercise of the police power in the interest of public health. The matter is no longer an open question." (citations omitted)). Cite error: The named reference "beck" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Pratt E, Rawson RD, Rubin M (2002). "Fluoridation at fifty: what have we learned?". The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 30 (3 Suppl): 117–21. PMID 12508513.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 17 Fed. Reg. 6743 (July 23, 1952).

- ^ a b 273 P.2d 859, 862-63 (Okl. 1954) (available at FindLaw for Legal Professionals)

- ^ 69 N.W.2d 242, 252 (Wis. 1955)

- ^ 127 N.E.2d 609, 613 (Ohio 1955)

- ^ Jones, Donna "Supreme Court turns down Watsonville's appeal to keep fluoride out of its water." Santa Cruz Sentinel. February 10, 2006.

- ^ Parkland Light & Water Co. v. Tacoma-Pierce County Bd. of Health, 90 P.3d 37 (Wash. 2004)

- ^ Pure Water Committee of W. MD., Inc. v. Mayor and City Council of Pure Water Comm. of W. MD., Inc. v. Mayor and City Council of Cumberland, MD. Not Reported in F.Supp.2d, 2003 WL 22095654 (D.Md. 2003)

- ^ Espronceda v. City of San Antonio, Not Reported in S.W.3d, 2003 WL 21203878 (Tex. App.-San Antonio 2003)