Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21: Difference between revisions

False info. IAF never nicknamed it as suggested here. Infact the reference given to validate that claim, proves exactly the opposite. |

|||

| Line 467: | Line 467: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commons|Category:Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21|Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21}} |

{{Commons|Category:Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21|Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21}} |

||

*[http://www.czechairspotters.com/search.php?generic_type=t1&airline=18&airport=&category=&author=&order=1&per_page=15 MiG-21 in Czech Air Force] |

|||

*[http://militarypedia.corran.pl/wiki/Mikojan_Gurewicz_MiG-21_w_Wojsku_Polskim List of all MiG-21 fighters used by Polish Air Force] |

*[http://militarypedia.corran.pl/wiki/Mikojan_Gurewicz_MiG-21_w_Wojsku_Polskim List of all MiG-21 fighters used by Polish Air Force] |

||

*[http://www.mig-21.de/ MiG-21.de] |

*[http://www.mig-21.de/ MiG-21.de] |

||

Revision as of 10:40, 29 December 2011

| MiG-21 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Romanian MiG-21UM Lancer B | |

| Role | Fighter |

| Manufacturer | Mikoyan-Gurevich OKB |

| Designer | Artem Mikoyan |

| First flight | 14 February 1955 (Ye-2) |

| Introduction | 1959 (MiG-21F) |

| Retired | 1990s (Russia) |

| Status | In active service (see list) |

| Primary users | Soviet Air Force Polish Air Force Indian Air Force Romanian Air Force |

| Produced | 1959 (MiG-21F) to 1985 (MiG-21bis) |

| Number built | 11,496[1] (10,645 produced in the USSR, 194 in Czechoslovakia, 657 in India) |

| Variants | Chengdu J-7 |

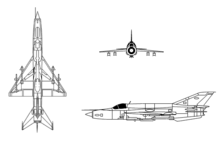

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 (Template:Lang-ru; NATO reporting name "Fishbed") is a supersonic jet fighter aircraft, designed by the Mikoyan-Gurevich Design Bureau in the Soviet Union. It was popularly nicknamed "balalaika", from the aircraft's planform-view resemblance to the Russian stringed musical instrument or ołówek (Template:Lang-en) by Polish pilots due to the shape of its fuselage.[2] Early versions are considered second-generation jet fighters, while later versions are considered to be third-generation jet fighters. Some 50 countries over four continents have flown the MiG-21, and it still serves many nations a half-century after its maiden flight. The fighter made aviation records. At least by name, it is the most-produced supersonic jet aircraft in aviation history and the most-produced combat aircraft since the Korean War, and it had the longest production run of a combat aircraft (1959 to 1985 over all variants).[1]

Development

The MiG-21 jet fighter was a continuation of Soviet jet fighters, starting with the subsonic MiG-15 and MiG-17, and the supersonic MiG-19. A number of experimental Mach 2 Soviet designs were based on nose intakes with either swept-back wings, such as the Sukhoi Su-7, or tailed deltas, of which the MiG-21 would be the most successful.

Development of what would become the MiG-21 began in the early 1950s, when Mikoyan OKB finished a preliminary design study for a prototype designated Ye-1 in 1954. This project was very quickly reworked when it was determined that the planned engine was underpowered; the redesign led to the second prototype, the Ye-2. Both these and other early prototypes featured swept wings—the first prototype with delta wings as found on production variants was the Ye-4. The Ye-4 made its maiden flight on 16 June 1955 and made its first public appearance during the Soviet Aviation Day display at Moscow's Tushino airfield in July 1956. The MiG-21 was the first successful Soviet aircraft combining fighter and interceptor characteristics in a single aircraft. It was a lightweight fighter, achieving Mach 2 with a relatively low-powered afterburning turbojet, and is thus comparable to the American Lockheed F-104 Starfighter and Northrop F-5 Freedom Fighter and the French Dassault Mirage III.[1] Its basic layout was used for numerous other Soviet designs; delta-winged aircraft included Su-9 interceptor and the fast E-150 prototype from MiG bureau while the mass-produced successful front fighter Su-7 and Mikoyan's I-75 experimental interceptor combined a similar fuselage shape with swept-back wings. However, the characteristic layout with the shock cone and front air intake did not see widespread use outside the USSR and finally proved to have limited development potential, mainly because of the very small space available for the radar.

Like many aircraft designed as interceptors, the MiG-21 had a short range. This was not helped by a design defect where the center of gravity shifted rearwards once two-thirds of the fuel had been used. This had the effect of making the plane uncontrollable, resulting in an endurance of only 45 minutes in clean condition. The issue of the short endurance and low fuel capacity of the MiG-21F, PF, PFM, S/SM and M/MF variants—though each had a somewhat greater fuel capacity than its predecessor—led to the development of the MT and SMT variants. These had a range increase of 250 km (155 mi) compared to the MiG-21SM, but at the cost of worsening all other performance figures (such as a lower service ceiling and slower time to altitude).[1]

The delta wing, while excellent for a fast-climbing interceptor, meant any form of turning combat led to a rapid loss of speed. However, the light loading of the aircraft could mean that a climb rate of 235 m/s (46,250 ft/min) was possible with a combat-loaded MiG-21bis,[1] not far short of the performance of the later F-16A. Given a skilled pilot and capable missiles, it could give a good account of itself against contemporary fighters. It was replaced by the newer variable-geometry MiG-23 and MiG-27 for ground support duties. However, not until the MiG-29 would the Soviet Union ultimately replace the MiG-21 as a maneuvering dogfighter to counter new American air superiority types.

The MiG-21 was exported widely and continues to be used. The aircraft's simple controls, engine, weapons, and avionics were typical of Soviet-era military designs. The use of a tail with the delta wing aids stability and control at the extremes of the flight envelope, enhancing safety for lower-skilled pilots; this in turn enhanced its marketability in exports to developing countries with limited training programs and restricted pilot pools. While technologically inferior to the more advanced fighters it often faced, low production and maintenance costs made it a favorite of nations buying Eastern Bloc military hardware. Several Russian, Israeli and Romanian firms have begun to offer upgrade packages to MiG-21 operators, designed to bring the aircraft up to a modern standard, with greatly upgraded avionics and armaments.[1]

Due to the lack of available information, early details of the MiG-21 were often confused with those of the similar Sukhoi fighters also under development. Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1960–1961 describes the "Fishbed" as a Sukhoi design, and uses an illustration of the Su-9 'Fishpot'.

Production

A total of 10,645 aircraft were built in the USSR. They were produced in three factories: GAZ 30 (3,203 aircraft) in Moscow (also known as Znamya Truda), GAZ 21 (5,765 aircraft)in Gorky [N 1] and at GAZ 31 (1,678 aircraft) in Tbilisi.[clarification needed] Generally, Gorky built single-seaters for the Soviet forces. Moscow built single-seaters for export and Tbilisi manufactured the twin-seaters both for export and for the USSR, though there were exceptions. The MiG-21R and MiG-21bis for export and for the USSR were built in Gorky, 17 single-seaters were built in Tbilisi (MiG-21 and MiG-21F), the MiG-21MF was first built in Moscow and then Gorky, and the MiG-21U was built in Moscow as well as in Tbilisi.[1]

| Gorky | 83 MiG-21F; 513 MiG-21F-13; 525 MiG-21PF; 233 MiG-21PFL; 944 MiG-21PFS/PFM; 448 MiG-21R; 145 MiG-21S/SN; 349 MiG-21SM; 281 MiG-21SMT; 2013 MiG-21bis; 231 MiG-21MF |

|---|---|

| Moscow | MiG-21U (all export units); MiG-21PF (all export units); MiG-21FL (all units not built by HAL); MiG-21M (all); 15 MiG-21MT (all) |

| Tbilisi | 17 MiG-21 and MiG-21F; 181 MiG-21U izdeliye 66–400 and 66–600 (1962–1966); 347 MiG-21US (1966–1970); 1133 MiG-21UM (1971 to end) |

A total of 194 MiG-21F-13s were built under licence in Czechoslovakia, and Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd. of India built 657 MiG-21FL, MiG-21M and MiG-21bis (of which 225 were bis)

Design

The MiG-21 has a delta wing. The sweep angle on the leading edge is 57° with a TsAGI S-12 airfoil. The angle of incidence is 0° while the dihedral angle is −2°. On the trailing edge there are ailerons with an area of 1.18 m², and flaps with an area of 1.87 m². In front of the ailerons there are small wing fences.

The fuselage is a semi-monocoque with an elliptical profile with a maximum width of 1.24 m (4 ft 1 in). The air flow to the engine is regulated by a cone in the air intake. Up until the MiG-21PF it was three staged. At speeds up to Mach 1.5 it is fully retracted, between speeds of Mach 1.5 and Mach 1.9 it is in the middle position, and with speeds higher than Mach 1.9 it is in the maximum forward position. On the MiG-21PF it adapts to the actual speed, according to the UVD-2M system aboard the aircraft, which monitors the pressure in front and behind the compressor of the engine. On both side of the nose there are gills to supply the engine with more air while on the ground and during takeoff. In the first variant of the MiG-21, the pitot tube is on the bottom of the nose; after the MiG-21P, every version of the −21 has this tube situated on the top of the air intake.

The cabin is pressurized and air conditioned. Prior to the MiG-21PFM the canopy is hinged at the front. When ejecting, the SK-1 ejection seat connects with the canopy making a capsule to enclose the pilot and protect him from the airflow, after which it would separate and the pilot would parachute down. However, the canopy took too long to separate and some pilots were killed after ejecting at low altitudes. On the MiG-21PFM the canopy is hinged on the right side of the cockpit.

On the belly of the plane there are three air brakes, two at the front and one at the back. The front brakes have an area of 0.76 m², and a deflection angle of 35°. The back one has an area of 0.46 m² and a deflection angle of 40°. The usage of the back air brake is blocked if the plane carries an external fuel tank. Behind the air brakes are the bays for the main landing gear. Under the body, just behind the trailing edge of the wing, two JATO rockets can be attached. The front part of the fuselage ends with former #28. Beginning with former #28a is the back part of the fuselage, which is removable for engine maintenance.

The empennage of the MiG-21 consists of a vertical stabilizer, a stabilator and a small fin on the bottom of the tail to improve yaw control. The vertical stabilizer has a sweep angle of 60° and an area of 5.32 m² (on earlier version 3.8 m²) and a rudder. The stabilator has a sweep angle of 57°, an area of 3.94 m² and a span of 2.6 m.

A tricycle type undercarriage with a nose gear. The main landing gear has tires 800 mm in diameter and 600 mm in width (till the MiG-21P; 660x200 mm). The wheels of the main landing gear retract in the fuselage after rotating 87°, the shock absorbers retract in the wing. The nose gear retracts forward in the fuselage under the radar.

Operational history

India

In 1961, the Indian Air Force (IAF) opted to purchase the MiG-21 over several other Western competitors because the Soviet Union offered India full transfer of technology and rights for local assembly.[3] In 1964, the MiG-21 became the first supersonic fighter jet to enter service with the IAF. Due to limited induction numbers and lack of pilot training, the IAF MiG-21 played a limited role in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.[4] However, the IAF gained valuable experience while operating the MiG-21 for defensive sorties during the war.[4] The positive feedback from IAF pilots during the 1965 war prompted India to place more orders for the fighter jet and also invest heavily in building the MiG-21's maintenance infrastructure and pilot training programs. By 1969, India had acquired more than 120 MiG-21s from the Soviet Union.[5]

Safety record

The safety record of the IAF's MiG-21s has raised concern in the media.[6][7] One source estimates that in the nine years from 1993 to 2002, the IAF lost over 100 pilots in 283 accidents.[7] During its service life, the IAF has lost at least 116 aircraft to crashes (not including those lost in combat), with 81 of those occurring since 1990.[8] Fuel-line leaks were identified as a major cause of such crashes in the aging Mig-21s in IAF. The fuel-lines were replaced/ repaired for the Mig-21s and crashes have been reduced drastically since late 2009. After more than a year, the first Mig-21 Bison crashed due to engine damage in Feb 2011 ,the second one a type-96 Mig-21 on 2 August 2011 killing the pilot also during a landing exercise and the third one on 6 September 2011 near Rajpura in Punjab. A MiG-21 combat aircraft of the IAF on Friday October 7th, 2011 crashed near Uttarlai airport in Rajasthan's Barmer district but the pilot ejected safely.

Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

The expansion of IAF MiG-21 fleet marked a growing India-Soviet Union military partnership which enabled India to field a formidable air force to counter Chinese and Pakistani threats.[9] The capabilities of the MiG-21 and the skills of its Indian pilots were soon put to the test during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. During the war, the MiG-21s played a crucial role in giving the IAF complete air superiority over vital points and areas in the western theater of the conflict.[10]

The 1971 war witnessed the first supersonic air combat in the subcontinent when an Indian MiG-21FLs claimed a PAF F-104 Starfighter with its GSh-23 twin-barrelled 23 mm cannon.[11] By the time the hostilities came to an end, the IAF MiG-21s had claimed four PAF F-104s, two PAF F.6, one PAF North American F-86 Sabre and one PAF Lockheed C-130 Hercules. According to one Western military analyst, the MiG-21s had clearly "won" the much anticipated air combat between the MiG-21 and the F-104 Starfighter.[12]

Because of the formidable performance of the MiG-21s, several nations, including Iraq, approached India for MiG-21 pilot training. By the early 1970s, more than 120 Iraqi pilots were being trained by the Indian Air Force.[13]

Kargil War and Atlantique Incident

It was also used as late as 1999 in the Kargil War, in which one Indian Air Force MiG-21 was shot down by a Pakistani hand-held "Stinger" surface-to-air missile.[14] The MiG-21's last known kill took place in 1999 during the Atlantique Incident, when two MiG-21 aircraft of the Indian Air Force intercepted and shot down an Breguet Atlantique reconnaissance aircraft of the Pakistani Navy with the R-60MK (AA-8 Aphid) air-to-air missile.

| Date | Aircraft Scoring Kill | Pilot | Victim |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 September 1965[15] | PAF F-86E | ? | IAF MiG-21F-13 |

| 4 December 1971[1] | IAF MiG-21FL "C1111" | FltLt Manbir Singh | PAF Sabre F.6 |

| 6 December 1971[15] | IAF MiG-21FL | FltLt Samar Bikram Shah | PAF F-6 |

| 6 December 1971[15] | IAF MiG-21FL | ? | PAF CC-130 |

| 11 December 1971[1] | IAF MiG-21FL | ? | |

| 12 December 1971[1] | IAF MiG-21FL "C750" | FltLt Bharat Bhushan Soni | PAF F-104A |

| 12 December 1971[1] | IAF MiG-21FL | FltLt Niraj Kukreja | PAF F-104A |

| 12 December 1971[1] | IAF MiG-21FL | SqnLdr Iqbal Singh Bindra | PAF F-104A |

| 14 December 1971[15] | PAF F-6 | A. A. Shafieff | IAF MiG-21FL |

| 16 December 1971[1] | IAF MiG-21FL | FltLt Samar Bikram Shah | PAF F-6 |

| 17 December 1971[1] | PAF F-86F | FltLt Maqsood Amir | IAF MiG-21FL "C716" |

| 17 December 1971[15] | IAF MiG-21FL | A. K. Datta | PAF F-104A |

| 17 December 1971[15] | IAF MiG-21FL | Samar Bikram Shah | PAF F-104A (damaged) |

| 1997[15] | 02xIAF MiG-21bis | Anza SAM | PAF |

| 10 August 1999[1] | IAF MiG-21bis (45 Sqn) | SqnLdr Prashant Kumar Bundela | PAF Br.1150 Atlantic |

Indonesia

The Indonesian Air Force purchased 22 MIG-21. Indonesian Air Force received 20 MIG21F-13 and MIG-21U were received in 1962 during Operation Trikora in 1962 in Western New Guinea conflict and Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation number of plane shot down unknown later given to United States.

Vietnam

The MiG-21, which initially became renowned during the Vietnam War, was designed for very short ground-controlled interception (GCI) missions, which is precisely the type of missions that it was employed for in the skies over North Vietnam.[16] The first MiG-21s arrived directly from the Soviet Union by ship in April 1966, and after being unloaded and assembled,[17] were transitioned into North Vietnam's oldest fighter unit; the 921st Fighter Regiment, which had been established on 3 February 1964 as a MiG-17 unit. Since the North Vietnamese Air Force's 923rd FR was newer and less experienced, they would continue to operate strictly MiG-17s; while the arrival of the MiG-19s (J6 versions) from Communist China in 1969 would create North Vietnam's only MiG-19 unit, the 925th FR. On 3 February 1972, North Vietnam commissioned their fourth and last Fighter Regiment of the war while engaged with the United States, the MiG-21PFM (Type 94) equipped 927th Fighter Regiment.[18]

Although thirteen of North Vietnam's flying aces attained their status while flying the MiG-21 – versus just three in the MiG-17. Many North Vietnamese pilots preferred the MiG-17, since the high wing loading of the MiG-21 made it relatively less maneuverable, and the less heavily framed canopy of the MiG-17 gave greater visibility.[19] However, this is not the impression perceived by British author Roger Boniface when he interviewed Pham Ngoc Lan and ace Nguyễn Nhật Chiêu (who scored victories flying both MiG-17 and MiG-21) – Pham Ngoc Lan told Boniface that "The MiG-21 was much faster, and it had two ATOLL missiles which were very accurate and reliable when fired between 1,000 and 1,200 yards."[20][verification needed], and Chiêu asserted that "...for me personally I preferred the MiG-21 because it was superior in all specifications in climb, speed and armament. The ATOLL missile was very accurate and I scored four kills with the ATOLL. [...] In general combat conditions I was always confident of a kill over a F-4 Phantom when flying a MiG-21."[21][verification needed]

Although the MiG-21 lacked the long-range radar, missiles, and heavy bombing payload of its contemporary multi-mission U.S. fighters, it proved a challenging adversary in the hands of experienced pilots, especially when used in high speed hit and run attacks under GCI control. MiG-21 intercepts of Republic F-105 Thunderchief strike groups were effective in downing US aircraft or forcing them to jettison their bomb loads.

After a million sorties and nearly 1,000 US aircraft losses, Operation Rolling Thunder came to an end on 1 November 1968.[22] A poor air-to-air combat loss-exchange ratios against the smaller, more agile enemy MiGs during the early part of the Vietnam War eventually led the USN to create their Navy Fighter Weapons School, also known as "Top Gun" at Miramar Naval Air Station on 3 March 1969.[23] The USAF quickly followed with their own version, titled the Dissimilar Air Combat Training (sometimes referred to as Red Flag) program. These two programs employed the subsonic Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and the supersonic F-5 Tiger II, as well as the Mach 2.4-capable USAF Convair F-106 Delta Dart, which mimicked the MiG-21.[24] Over the course of the air war, between 3 April 1965[25] and 8 January 1973, each side would ultimately claim favorable kill ratios.

Two MiG-21s were claimed shot down by U.S. Air Force Boeing B-52 Stratofortress tail gunners; the only confirmed air-to-air kills made by the B-52. The first aerial victory occurred on 18 December 1972, kill awarded to tail gunner SSgt Samuel Turner, who was awarded the Silver Star for his feat.[26] The second air to air kill took place on 24 December 1972, kill awarded to A1C Albert E. Moore for downing a MiG-21 over the Thai Nguyen railroad yards. Both actions occurred during Operation Linebacker II (also known as the Christmas Bombings).[27]

The biggest threat to North Vietnam during the war, had always been the Strategic Air Command's B-52 Stratofortress. Hanoi's MiG-17 and MiG-19 interceptors could not deal with those bombers at the altitude that they flew. In the summer of 1972, the NVAF was directed to train 12 MiG-21 pilots for the specific mission of attacking and shooting down B-52 bombers; with two-thirds of those pilots specifically trained in the night attack.[28] On 26 December 1972, just two days after Tail gunner Albert Moore downed his MiG-21, a VPAF (North Vietnamese Air Force) MiG-21MF (number 5121)[29] from the 921st Fighter Regiment, flown by Major Phạm Tuân over Hanoi, North Vietnam claimed responsibility for the first aerial combat kill of a U.S. Air Force Boeing B-52 Stratofortress in aviation history.[30] The Stratofortress had been above Hanoi at over 30,000 feet (9,100 m) during Operation Linebacker II, when Major Tuân launched two Atoll missiles from 2 kilometres, claiming to have destroyed one of the bombers flying in the three plane formation.[30] Other sources argue that his missiles failed to hit their mark, but as he was disengaging a B-52 from a three-bomber cell in front of his target took a hit from a SAM, exploding in mid-air: this may have caused Tuan to think his missiles destroyed the target he had been aiming for.[31]

The Vietnamese side also claims another kill to have taken place on 28 December 1972 by a MiG-21 from the 921st FR, this time flown by Vu Xuan Thieu. Thieu is said to perished in the explosion of a B-52 hit by his own missiles, having approached the target too closely.[32] In this case the Vietnamese version appears to be a complete fabrication: while one MiG-21 kill was claimed by Phantoms that night (this may have been Thieu's MiG), no B-52s were lost to any cause on the date of the claimed kill.[33]

The MiG-21's 3G limit on maneuverability at altitude and the limited arc from which its weapons could be launched contributed to the poor results.[34]

Year-by-Year Kill Claims involving MiG-21s[1]

- 1966: US claimed six MiG-21s destroyed; North Vietnam claimed seven F-4 Phantom IIs and 11 F-105 Thunderchiefs shot down by MiG-21s.

- 1967: US claimed 21 MiG-21s destroyed; North Vietnam claimed 17 F-105 Thunderchiefs, 11 F-4 Phantom IIs, two McDonnell RF-101 Voodoos, one Douglas A-4 Skyhawk, one Vought F-8 Crusader, one EB-66 Destroyer and three unidentified types shot down by MiG-21s.

- 1968: US claimed nine MiG-21s destroyed; North Vietnam claimed 17 US aircraft shot down by MiG-21s.

- 1969: US destroyed three MiG-21s; one Firebee UAV destroyed by a MiG-21.

- 1970: US destroyed two MiG-21s; North Vietnam claimed one F-4 Phantom and one CH-53 Sea Stallion helicopter shot down by MiG-21s.

- 1972: US claimed 51 MiG-21s destroyed; North Vietnam claimed 53 US aircraft shot down by MiG-21s, including two B-52 Stratofortress bombers. Soviet General Fesenko, the main Soviet adviser to the North Vietnamese Air Force in 1972,[32] recorded 34 MiG-21s, nine MiG-17s, and nine MiG-19s destroyed in 1972.[32]

Egyptian-Syrian-Israeli conflicts

The MiG-21 was also used extensively in the Middle East conflicts of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s by the air forces of Egypt, Syria and Iraq. The MiG-21 first encountered Israeli Mirage IIICs on 14 November 1964, but it was not until 14 July 1966 that the first MiG-21 was shot down. Another six Syrian MiG-21s were shot down by Israeli Mirages on 7 April 1967. The MiG-21 would also face F-4 Phantom IIs and A-4 Skyhawks, but was later outclassed by the more modern McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle and F-16 Fighting Falcon, which were acquired by Israel beginning in the mid-1970s.

During the opening attacks of the 1967 Six Day War, the Israeli Air Force struck Arab air forces in four attack waves. In the first wave, IDF aircraft claimed to have destroyed eight Egyptian aircraft in air-to-air combat, of which seven were MiG-21s; Egypt claims 10 Israeli aircraft destroyed,[citation needed] four or five of which were scored by MiG-21PFs. During the second wave the Israelis claimed four MiG-21s downed in air-to-air combat, and the third wave resulted in two Syrian and one Iraqi MiG-21s claimed destroyed in the air. The fourth wave destroyed some more Syrian MiG-21s on the ground. Overall, the Egyptians lost around 100 out of about 110 MiG-21s they had, almost all on the ground; the Syrians lost 35 of 60 MiG-21F-13s and MiG-21PFs in the air and on the ground.[1]

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (October 2009) |

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2011) |

Between the end of the Six Day War and the start of the War of Attrition, IDF Mirage fighters had six confirmed kills of Egyptian MiG-21s, in exchange for Egyptian MiG-21s scoring two confirmed and three probable kills against Israeli aircraft.[citation needed] During the War of Attrition itself, the Israelis claimed 56 confirmed kills against Egyptian MiG-21s, while Egyptian MiG-21s claimed 14 confirmed and 12 probable kills against IDF aircraft.[citation needed] During this same time period, from the end of the Six Day War to the end of the War of Attrition, the Israelis claimed a total of 25 Syrian MiG-21s destroyed; the Syrians claimed three confirmed and four probable kills of Israel aircraft.[1]

High losses to Egyptian aircraft and continuous bombing during the War of Attrition caused the Egyptians to ask the Soviet Union for help. In June 1970, Soviet pilots and SAM crews arrived with their equipment. On 22 June 1970, a Soviet pilot flying a MiG-21MF shot down an Israeli A-4E.[citation needed] After some more successful intercepts by Soviet pilots and another Israeli A-4 being shot down on 25 July,[citation needed] the Israelis decided to plan an ambush in response. On 30 July Israeli F-4s lured Soviet MiG-21s into an area where they were ambushed by Mirages. Asher Snir, flying a Mirage IIICJ, destroyed a Soviet MiG-21; Avihu Ben-Nun and Aviam Sela, both piloting F-4Es, each got a kill, and an unidentified pilot in another Mirage scored the fourth kill against the Soviet-flown MiG-21s. Three Soviet pilots were killed and the Soviets were alarmed by the losses. However, Soviet MiG-21 pilots and SAM crews destroyed a total of 21 Israeli aircraft, which helped to convince the Israelis to sign a ceasefire agreement.[1]

In September 1973 a large air battle erupted between the Syrians and the Israelis; the Israelis claimed a total of 12 Syrian MiG-21s destroyed, while the Syrians claimed eight kills[citation needed] scored by MiG-21s and admitted five losses.

During the Yom Kippur War, the Israelis claimed a total of 73 kills of Egyptian MiG-21s. Egypt claimed 27 kills of Israeli aircraft by its MiG-21s, plus eight probables.[1] However, according to most reliable sources, these were exaggerated claims as Israeli air-to-air combat losses for the entire war did not exceed five to eight.[35][36]

On the Syrian front of the war, 6 October 1973 saw a flight of Syrian MiG-21MFs shoot down an IDF A-4E and a Mirage IIICJ while losing three of their own to Israeli IAI Neshers.[citation needed] On 7 October, Syrian MiG-21MFs downed two Israeli F-4Es, three Mirage IIICJs and an A-4E[citation needed] while losing two of their MiGs to Neshers and one to an F-4E, plus two to friendly SAM fire. Iraqi MiG-21PFs also operated on this front, and on that same day destroyed two A-4Es while losing one MiG.[citation needed] On 8 October 1973 Syrian MiG-21PFMs downed three F-4Es,[citation needed] but six of their MiG-21s were lost. By the end of the war, Syrian MiG-21s claimed a total of 30 confirmed kills against Israeli aircraft; 29 MiG-21s were claimed as destroyed by the IDF.[1]

Between the end of the Yom Kippur War and the start of the 1982 Lebanon War, the Israelis had received modern F-15s and F-16s, which were far superior to the old Syrian MiG-21MFs. According to the IDF, these new planes accounted for the destruction of 24 Syrian MiG-21s over this time period, though the Syrians did claim five kills against IDF aircraft with their MiG-21s armed with outdated K-13 missiles.[1]

The 1982 Lebanon War started on 6 June 1982, and in the course of that war the IDF claimed to have destroyed about 45 Syrian MiG-21MFs. The Syrians claimed two confirmed and 15 probable kills of Israeli aircraft.[1] This air battle was the largest to occur since the Korean War.

Other Middle East conflicts

Egypt would be shipped some American Sidewinder missiles, and these were fitted to their MiG-21s and successfully used in combat against Libyan MiG-23s during the brief Libyan-Egyptian War of July 1977.

| Date | Aircraft Scoring Kill | Victim |

|---|---|---|

| 22 July 1977 | LARAF Mirage 5DE | EAF MiG-21MF |

| 23 July 1977 | EAF MiG-21MFs | 3 (or 4) LARAF Mirage + 1 LARAF MiG-23MS |

| 1979 | EAF MiG-21MF | LARAF MiG-23MS |

Libya

Libyan MiG-21s saw limited service during the 2011 Libyan Civil War.[37] On 15 March 2011, one MiG-21bis and one MiG-21UM flown by defector Libyan air force pilots who joined the rebellion, flew from Ghardabiya AB (near Sirte) and landed at Benina airport to became part of the Free Libyan Air Force. On 17 March 2011, after it ran out of fuel, the MiG-21UM crashed after takeoff from Benina airport.[38]

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia purchased its first batch of MiG-21s in 1962 from the Soviet Union. In the period from 1962 to the early 1980s Yugoslavia had purchased up to 216 MiG-21s in nine variants. From 1964 to 1992, about 80 aircraft had been lost in accidents.[citation needed] Yugoslav Air force units that operated MiG-21 were the 204th fighter-aviation regiment at Batajnica Air Base (126th, 127th and 128th fighter-aviation squadrons), 117th fighter-aviation regiment at Željava Air Base (124th and 125th fighter-aviation squadron and 352nd recon squadron), 83rd fighter-aviation regiment at Slatina Air Base (123rd and 130th fighter aviation squadron), 185th fighter-bomber-aviation squadron (129th fighter-aviation squadron) at Pula and 129th training center at Batajnica air base.

During the early stages of the 1991–1995 Yugoslav wars the Yugoslav People's Army used MiG-21s in a ground-attack role, while Croatian and Slovenian forces did not have air forces at the beginning of the war. Aircraft from air bases in Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina were relocated to air bases in Serbia. Detailed records show at least seven MiG-21s were shot down by AA defenses in Croatia and Bosnia.[39] A MiG-21 piloted by Emir Šišić shot down a EU helicopter that had entered Croatian aerospace with full knowledge of the Yugoslav flight control (but neglected warnings).[40]

Croatia acquired three MiG-21s in 1992 through defections by Croatian pilots serving with the JNA, two of which were lost in subsequent actions – one to Serbian air defenses, the other in a friendly fire accident.[41] In 1993, Croatia purchased about 40 MiG-21s in violation of an arms embargo,[41] but only about 20 of these entered service, while the rest were used for spare parts. Croatia used them alongside the sole remaining defector for ground attack missions in operations Flash (during which one was lost) and Storm. The only air-to-air action for Croatian MiGs was an attempt by two of them to intercept J-22 Oraos of Republika Srpska Air Force on ground attack mission on 7 August 1995. After some maneuvering, both sides disengaged without firing.[41]

Remaining Yugoslav MiG-21s were flown to Serbia by 1992 and continued their service in the newly created Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. During the 1999 NATO attack on Yugoslavia, 33 MiG-21s were destroyed on the ground.[39]

Africa

During the Cold War MiG-21s were supplied to many sub-Saharan African nations by the Soviets. The Cubans also flew their MiG-21s in some of the conflicts.

One of the more notable uses of MiG-21s in combat occurred during the Angolan Civil War in the hands of the People's Air and Air Defence Force of Angola. Cuban Air Force pilots also flew MiG-21s over Angola during the war. MiG-21s were used as fighter-bombers and most losses were due to ground fire. However, both Angolan and Cuban MiG-21s often had encounters with South African Air Force Mirages. On 6 November 1981, Major Johann Rankin, flying a Mirage F.1CZ, scored the SAAF's first kill since the Korean War, downing the MiG-21MF of Lt. Danacio Valdez. On 5 October 1982, a SAAF Mirage IIICZ damaged a MiG-21MF with cannon fire, but the MiG managed to return to base safely.[1] The SAAF acquired a MiG-21 through defection[dubious – discuss] and the aircraft currently resides in its museum.

During the Ogaden War of 1977–78, American-supplied Ethiopian F-5As met Somalian MiG-21MFs in combat several times. In one lopsided incident, two F-5As engaged four MiG-21MFs that were armed only with bombs. The pilots destroyed two and then watched with amazement as the two remaining MiG-21s collided with each other.[1] The Ethiopian F-5As claimed 10 Somali MiG-21MFs; in return, Somali MiG-21MFs claimed four Ethiopian MiG-21MFs, one Canberra bomber and three Douglas DC-3s.[1] Ironically, Ethiopia also received MiG-21s. The Ethiopian MiG-21s were used to bomb Somali forces in the final Ethiopian counter-attack.[1]

MiG-21s, along with its Chinese copy (the F-7), flew ground sorties during the First and Second Congo Wars, sometimes being piloted by mercenaries.

Romania

Beginning in 1993, Russia did not offer spare parts for the MiG-23 and MiG-29 for the Romanian Air Force. Initially, this was the context for the modernization of the Romanian MiG-21's with Elbit Systems, and because it was easier for the Romanians to maintain these fighter jets. A total of 110 MiG-21s were modernized under the LanceR designation. Today, only 48 LanceRs are operational for the RoAF. It can use both Western and Eastern armament such as the R-60M, R-73, Magic 2, or Python III missiles. They will be replaced in 2012 when new fighter jets will arrive, such as the F-16, F/A-18, Eurofighter Typhoon or Gripen. However due to lack of funds the MiG-21 LanceR may fly for years longer.[42]

Known MiG-21 aces

Several pilots have attained ace status (five or more aerial victories/kills) while flying the MiG-21. Nguyễn Văn Cốc of the Vietnam People's Air Force (VPAF; also referred to as the NVAF), who scored nine kills in MiG-21s is regarded as the most successful.[43] Twelve other VPAF pilots were credited with five or more aerial victories while flying the MiG-21: Phạm Thanh Ngân,[1] Nguyễn Hồng Nhị and Mai Văn Cường (both eight kills); Đặng Ngọc Ngự[1] (seven kills), Vũ Ngọc Đỉnh,[1] Nguyễn Ngọc Độ,[1] Nguyễn Nhật Chiêu,[1] Lê Thanh Đạo,[1] Nguyễn Đăng Kỉnh,[1] Nguyễn Đức Soát,[1] and Nguyễn Tiến Sâm[1] (six kills each), and Nguyễn Văn Nghĩa[1] (five kills). Col. Vadim Petrovich Shchbakov according to the 18th Report of the US government's "Task Force Russia", achieved ace status with six kills in the Vietnam War while serving as a pilot instructor.[44]

Additionally, three Syrian pilots are known to have attained ace status while flying the MiG-21. Syrian airmen: M. Mansour[45] recorded five solo kills (with one additional probable), B. Hamshu[45] scored five solo kills, and A. el-Gar[45] tallied four solo and one shared kill, all three during the 1973–1974 engagements against Israel.

Due to the incomplete nature of available records, there are several pilots who have un-confirmed aerial victories (probable kills), which when confirmed would award them "Ace" Status: S. A. Razak[46] of the Iraqi Air Force with four known kills scored during the Iran-Iraq War (until 1991; sometimes referred to as the Persian Gulf War), A. Wafai[47] of the Egyptian Air Force with four known kills against Israel.

For specific information on kills scored by and against MiG-21s sorted by country see the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 operators page.

Variants

Operators

Current operators

This list does not include operators of Chinese copies / licensed manufactured versions known as the Chengdu J-7. Information is based on Mig-21 (2008).[1]

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan Bulgaria (photo in flight 2011)

Bulgaria (photo in flight 2011) Cambodia

Cambodia Croatia

Croatia Cuba

Cuba Egypt

Egypt Eritrea

Eritrea Ethiopia

Ethiopia India

India Libyan Republic

Libyan Republic Mali

Mali North Korea

North Korea Romania

Romania Serbia

Serbia Syria

Syria Uganda

Uganda Vietnam

Vietnam Yemen

Yemen Zambia

Zambia

Former operators

Afghanistan

Afghanistan Albania

Albania Algeria

Algeria Angola

Angola Bangladesh

Bangladesh Belarus

Belarus Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso Chad

Chad China (Replaced by similar-looking Chengdu J-7. Other than Mig-21F13 supplied by Soviet Union, China also traded a small amount of Mig-21MFs with J-7 export variations, then developed J-7C/D based on Mig-21MFs. The deal was between China and a certain Middle East country. [48])

China (Replaced by similar-looking Chengdu J-7. Other than Mig-21F13 supplied by Soviet Union, China also traded a small amount of Mig-21MFs with J-7 export variations, then developed J-7C/D based on Mig-21MFs. The deal was between China and a certain Middle East country. [48]) Congo, Republic of the

Congo, Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of

Congo, Democratic Republic of Czechoslovakia (Passed on to the Czech Republic and Slovakia.)

Czechoslovakia (Passed on to the Czech Republic and Slovakia.) Czech Republic

Czech Republic East Germany (Passed on to Germany after reunification.)

East Germany (Passed on to Germany after reunification.) Finland

Finland Germany

Germany Georgia

Georgia Guinea

Guinea Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau Hungary

Hungary Indonesia

Indonesia Iran (Ex-Iraqi MiG-21 received after Iran-Iraq War)

Iran (Ex-Iraqi MiG-21 received after Iran-Iraq War) Iraq (As of Saddam's Era)

Iraq (As of Saddam's Era) Israel (Captured from Syria and Egypt)

Israel (Captured from Syria and Egypt) Kyrgyzstan (Still houses some 100 partly dismantled fighters.)

Kyrgyzstan (Still houses some 100 partly dismantled fighters.) Laos

Laos Libya (As of Gaddafi's Era)

Libya (As of Gaddafi's Era) Madagascar

Madagascar Mongolia

Mongolia Mozambique

Mozambique Namibia

Namibia Nigeria

Nigeria Poland

Poland Russia

Russia Slovakia

Slovakia Somalia

Somalia Soviet Union (Passed on to successor states.)

Soviet Union (Passed on to successor states.) Sudan

Sudan Tanzania

Tanzania Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan United States (Evaluation only.)

United States (Evaluation only.) Ukraine

Ukraine North Yemen (Passed on to Yemen after reunification.)

North Yemen (Passed on to Yemen after reunification.) South Yemen (Passed on to Yemen after reunification.)

South Yemen (Passed on to Yemen after reunification.) Yugoslavia (Passed on to successor states.)

Yugoslavia (Passed on to successor states.) Zaire (Four were exported to Zairean rebels by FR Yugoslavia [49]

Zaire (Four were exported to Zairean rebels by FR Yugoslavia [49] Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Civil operators

According to the FAA there are currently 44 privately owned MiG-21s in the U.S.[50] There are companies that purchase MiG-21s, MiG-15s and MiG-17s from Russia and other countries for sale to civilians for around $US450,000.[citation needed]

Specifications (Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21F-13)

(Specifications for other models can be found at:-Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 variants)

Data from Mikoyan MiG-21 (Famous Russian aircraft),[1]Combat Aircraft since 1945[51]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 2.05

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- English Electric Lightning

- Dassault Mirage III

- Lockheed F-104 Starfighter

- McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II

- Northrop F-5 Freedom Fighter/Tiger II

- SAAB J-35 Draken

Related lists

References

- Notes

- ^ Now called Nizhny Novgorod.

- Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an Gordon, Yefim. MiG-21 (Russian Fighters). Earl Shilton, Leicester, UK: Midland Publishing Ltd., 2008. ISBN 978-1-85780-257-3.

- ^ "MiG-21 – naddźwiękowy ołówek." (in Polish) lotniczapolska.pl, 6 September 2007. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ Mehrotra, Santosh. India and the Soviet Union: Trade and Technology Transfer. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0521362023.

- ^ a b Rakshak, Bharat. "The Canberra and the MiG-21." bharat-rakshak.com. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ Sharma, Shri Ram. India-USSR Relations: 1947–1971. Delhi: Discovery Publishing House, 1999. ISBN 978-8171414864.

- ^ Singh, Varinder Singh. "8 die in MiG-21 crash." Tribune News Service, 3 May 2002. Retrieved: 17 April 2007.

- ^ a b "Yet Another MiG Crash." Tribune India. Retrieved: 19 April 2007.

- ^ "MiG Crash Chronology."[dead link] Defence India. Retrieved: 19 April 2007.

- ^ Till, Geoffrey. Globalisation and Defence in the Asia-Pacific. London: Taylor & Francis, 2008. ISBN 978-0415440486.

- ^ "Air Force History." Globalsecurity. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ "The 1971 Liberation War: Supersonic Air Combat." Bharat-Rakshak.com. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ Coggins, Ed. Wings That Stay on. Nashville, KT: Turner Publishing Company, 2000. ISBN 978-1563115684.

- ^ Cooper, Tom. Arab MiG-19 and MiG-21 Units in Combat. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2004. ISBN 978-1841766553.

- ^ "Indian pilot 'killed in cold blood'." BBC, 30 May 1999. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Indian Air-to-Air Victories since 1948." acig.org. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ Michel 1997, p. 81.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, pp. 6, 77.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, p. 27.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, p. 12.

- ^ Boniface 2005, p. 190.

- ^ Boniface 2005, p. 192.

- ^ Michel 1997, p. 149.

- ^ Michel 1997, p. 186.

- ^ Michel 1997, p. 187.

- ^ Anderton 1987, pp. 70–71.

- ^ "The plaque on SSgt Turner's grave." waymarking.com. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Linebacker II." The Colorado Springs Gazette, 16 July 2007.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, p. 61.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, p. 66 photo.

- ^ a b Toperczer 2001, p. 66.

- ^ Michel 2002, pp. 205–206.

- ^ a b c Toperczer 2001, p. 67.

- ^ Michel 2002, pp. 213.

- ^ "MiG 21 Fishbed C and E Aerial Tactics." foia.af.mil. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ Pollack 2004, p. 124.

- ^ Herzog 1975, p. 259.

- ^ "Libyan Conflict: Fixed-wing Combat Aircraft make an Appearance ." The Boresight, 20 March 2011. Retrieved: 9 May 2011.

- ^ "MiG-21UM/bis Fishbed K." Aviation Safety Net. Retrieved: 9 May 2011.

- ^ a b Avijacija bez granica Template:Sr icon avijacijabezgranica.com. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Austrian Radar Plots." acig.org. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ a b c "MiGs Over Croatia." acig.org. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ Dirk Jan de Ridder and Menso van Westrhenen. "Young at 95!" Air Forces Monthly magazine, February 2009 issue, p. 54.

- ^ "North Vietnamese Aces." AcePilots.com. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Task Force Russia 18th Report." lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ a b c "Syrian Air-to-Air Victories since 1948." acig.org. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Iraqi Air-to-Air Victories since 1967." acig.org.Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Egyptian Air-to-Air Victories since 1948." acig.org. Retrieved: 1 December 2010.

- ^ "China Mig-21MF Trade." AirForceWorld.com. Retrieveda; 5 November 2011.

- ^ http://www.acig.org/artman/publish/article_190.shtml

- ^ FAA Registry - Aircraft - Make / Model Inquiry

- ^ Wilson 2000, p. 100.

- ^ with pitot tube

- Bibliography

- Anderton, David A. North American F-100 Super Sabre. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Limited, 1987. ISBN 0-85045-622-2.

- Boniface, Roger. Fighter Pilots of North Vietnam: An Account of their Combats 1965 to 1975. Gamlingay, Sandy, UK: Authors On Line, 2005. ISBN 978-0755202034.

- Eden, Paul. The Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft, London: Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1-904687-84-9

- Gordon, Yefim. Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15: The Soviet Union's Long-Lived Korean War Fighter. Hinckley, UK: Midland, 2001. ISBN 1-85780-105-9.

- Gordon, Yefim. Mikoyan MiG-21 (Famous Russian aircraft). Hinckley, UK: Midland, 2008. ISBN 978-1-85780-257-3.

- Herzog, Chaim. The War of Atonement. Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1975. ISBN 0-316-35900-9.

- Michel III, Marshall L. Clashes; Air Combat Over North Vietnam 1965–1972. Annapolis, Maryland, USA: Naval Institute Press, 2007, First edition 1997. ISBN 1-59114-519-8.

- Michel III, Marshall L. The 11 days of Christmas. New York: Encounter Books, 2002. ISBN 1-893554-27-9.

- Pollack, Kenneth M. Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948–1991 London: Bison Books, 2004. ISBN 0-80328-783-6.

- Toperczer, István. MiG-21 Units of the Vietnam War (Osprey Combat Aircraft, 29). Oxford, UK: Osprey Pub, 2001. ISBN 1-84176-263-6.

- Wilson, Stewart. Combat Aircraft since 1945. Fyshwick, Australia: Aerospace Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-875671-50-1.

External links

- MiG-21 in Czech Air Force

- List of all MiG-21 fighters used by Polish Air Force

- MiG-21.de

- MIG-21 Fishbed from Russian Military Analysis

- MiG-21 FISHBED from Global Security.org

- MiG-21 Fishbed from Global Aircraft

- Cuban MiG-21

- Cuban MiG-21 in Angola

- Warbird Alley: MiG-21 page – Information about privately owned MiG-21s

- African flown MiGs, including the MiG-21

- Mig Alley USA, Aviation Classics, Ltd Reno, NV[dead link]

- MiG 21, Warbirds of Delaware, Reno Photos

- Chinese J-7 fighter jet family