Comparative advantage: Difference between revisions

Cleaned up the →The Ricardian Model: and added two figures. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[David Ricardo]] developed the classical theory of comparative advantage in [[1817]] to why explain countries engage in [[international trade]] even when one country's workers are more efficient at producing ''every'' single good than workers in other countries. He demonstrated that if two countries capable of producing the same two commodities engage in [[free trade]], then each country will increase its overall consumption by exporting the good for which it has a comparative advantage while importing the other good, provided that there exist differences in [[labor productivity]] between both countries.<ref>Baumol, William J. and Alan S. Binder, 'Economics: Principles and Policy'', [p. 50 http://books.google.com/books?id=6Kedl8ZTTe0C&lpg=PA49&dq=%22law%20of%20comparative%20advantage%22&pg=PA50#v=onepage&q=%22law%20of%20comparative%20advantage%22&f]</ref><ref name="econbook">{{cite book |last1=O'Sullivan |first1=Arthur |authorlink1=Arthur O'Sullivan (economist) |last2=Sheffrin |first2=Steven M. |title=Economics: Principles in Action |url=http://www.amazon.com/Economics-Principles-Action-OSullivan/dp/0130630853 |accessdate=May 3, 2009 |edition=2nd |series=The Wall Street Journal:Classroom Edition |year=2003 |origyear= January 2002|publisher= Pearson Prentice Hall: Addison Wesley Longman|location=Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458 |isbn=0-13-063085-3 |page= 444 }}</ref> Widely regarded as one of the most powerful<ref>{{cite web|url=http://internationalecon.com/Trade/Tch40/T40-0.php |title=International Trade Theory and Policy|author=Steven M Suranovic|year=2010}}</ref> yet counter-intuitive<ref>{{cite web|url=http://web.mit.edu/krugman/www/ricardo.htm | author=Krugman, Paul|title=Ricardo's Difficult Idea |year=1996 |accessdate=2014-08-09}}</ref> insights in economics, Ricardo's theory implies that comparative advantage rather than [[absolute advantage]] is responsible for much of international trade. |

[[David Ricardo]] developed the classical theory of comparative advantage in [[1817]] to why explain countries engage in [[international trade]] even when one country's workers are more efficient at producing ''every'' single good than workers in other countries. He demonstrated that if two countries capable of producing the same two commodities engage in [[free trade]], then each country will increase its overall consumption by exporting the good for which it has a comparative advantage while importing the other good, provided that there exist differences in [[labor productivity]] between both countries.<ref>Baumol, William J. and Alan S. Binder, 'Economics: Principles and Policy'', [p. 50 http://books.google.com/books?id=6Kedl8ZTTe0C&lpg=PA49&dq=%22law%20of%20comparative%20advantage%22&pg=PA50#v=onepage&q=%22law%20of%20comparative%20advantage%22&f]</ref><ref name="econbook">{{cite book |last1=O'Sullivan |first1=Arthur |authorlink1=Arthur O'Sullivan (economist) |last2=Sheffrin |first2=Steven M. |title=Economics: Principles in Action |url=http://www.amazon.com/Economics-Principles-Action-OSullivan/dp/0130630853 |accessdate=May 3, 2009 |edition=2nd |series=The Wall Street Journal:Classroom Edition |year=2003 |origyear= January 2002|publisher= Pearson Prentice Hall: Addison Wesley Longman|location=Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458 |isbn=0-13-063085-3 |page= 444 }}</ref> Widely regarded as one of the most powerful<ref>{{cite web|url=http://internationalecon.com/Trade/Tch40/T40-0.php |title=International Trade Theory and Policy|author=Steven M Suranovic|year=2010}}</ref> yet counter-intuitive<ref>{{cite web|url=http://web.mit.edu/krugman/www/ricardo.htm | author=Krugman, Paul|title=Ricardo's Difficult Idea |year=1996 |accessdate=2014-08-09}}</ref> insights in economics, Ricardo's theory implies that comparative advantage rather than [[absolute advantage]] is responsible for much of international trade. |

||

Since 1817, economists have attempted to generalize the [[Ricardian model]] and derive the principle of comparative advantage in broader settings, most notably in the [[neoclassical economics|neoclassical]] ''specific factors'' [[Ricardo-Viner]] and ''factor proportions'' [[Heckscher-Ohlin]] models. Subsequent developments in the [[new trade theory]], motivated in part by the empirical shortcomings of the H-O model and its inability to explain [[intra-industry trade]], have challenged the importance of comparative advantage to trade.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Maneschi|first1=Andrea|title=Comparative Advantage in International Trade: A Historical Perspective|date=1998|publisher=Elgar|location=Cheltenham|pages=6–13}}</ref> Nonetheless, economists like [[Alan Deardorff]],<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Deardorff|first1=Alan|title=The General Validity of the Law of Comparative Advantage|journal=Journal of Political Economy|date=Oct. 1980|volume=88|issue=5|pages=941–957}}</ref> [[Avinash Dixit]], and [[Victor D. Norman]]<ref>{{cite book|last1=Dixit|first1=Avinash|last2=Norman|first2=Victor|title=Theory of International Trade: A Dual, General Equilibrium Approach|date=1980|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=Cambridge|pages=93–126}}</ref> have responded with weaker generalizations of the principle of comparative advantage, in which countries will only ''tend'' to export goods for which they have a comparative advantage. |

Since 1817, economists have attempted to generalize the [[Ricardian model]] and derive the principle of comparative advantage in broader settings, most notably in the [[neoclassical economics|neoclassical]] ''specific factors'' [[Specific Factors Model|Ricardo-Viner]] and ''factor proportions'' [[Heckscher-Ohlin]] models. Subsequent developments in the [[new trade theory]], motivated in part by the empirical shortcomings of the H-O model and its inability to explain [[intra-industry trade]], have challenged the importance of comparative advantage to trade.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Maneschi|first1=Andrea|title=Comparative Advantage in International Trade: A Historical Perspective|date=1998|publisher=Elgar|location=Cheltenham|pages=6–13}}</ref> Nonetheless, economists like [[Alan Deardorff]],<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Deardorff|first1=Alan|title=The General Validity of the Law of Comparative Advantage|journal=Journal of Political Economy|date=Oct. 1980|volume=88|issue=5|pages=941–957}}</ref> [[Avinash Dixit]], and [[Victor D. Norman]]<ref>{{cite book|last1=Dixit|first1=Avinash|last2=Norman|first2=Victor|title=Theory of International Trade: A Dual, General Equilibrium Approach|date=1980|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=Cambridge|pages=93–126}}</ref> have responded with weaker generalizations of the principle of comparative advantage, in which countries will only ''tend'' to export goods for which they have a comparative advantage. |

||

==The classical theory== |

==The classical theory== |

||

Revision as of 12:50, 17 August 2014

The theory of comparative advantage is an economic theory about the potential gains from trade for individuals, firms, or nations that arise from differences in their factor endowments or technological progress.[1] In an economic model, an agent has a comparative advantage over another in producing a particular good if she can produce that good at a lower relative opportunity cost or autarky price, i.e. at a lower relative marginal cost prior to trade.[2] The closely-related law or principle of comparative advantage holds that under free trade, an agent will produce more of and consume less of a good for which she has a comparative advantage.[3]

David Ricardo developed the classical theory of comparative advantage in 1817 to why explain countries engage in international trade even when one country's workers are more efficient at producing every single good than workers in other countries. He demonstrated that if two countries capable of producing the same two commodities engage in free trade, then each country will increase its overall consumption by exporting the good for which it has a comparative advantage while importing the other good, provided that there exist differences in labor productivity between both countries.[4][5] Widely regarded as one of the most powerful[6] yet counter-intuitive[7] insights in economics, Ricardo's theory implies that comparative advantage rather than absolute advantage is responsible for much of international trade.

Since 1817, economists have attempted to generalize the Ricardian model and derive the principle of comparative advantage in broader settings, most notably in the neoclassical specific factors Ricardo-Viner and factor proportions Heckscher-Ohlin models. Subsequent developments in the new trade theory, motivated in part by the empirical shortcomings of the H-O model and its inability to explain intra-industry trade, have challenged the importance of comparative advantage to trade.[8] Nonetheless, economists like Alan Deardorff,[9] Avinash Dixit, and Victor D. Norman[10] have responded with weaker generalizations of the principle of comparative advantage, in which countries will only tend to export goods for which they have a comparative advantage.

The classical theory

Adam Smith first alluded to the concept of absolute advantage as the basis for international trade in The Wealth of Nations:

"If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry employed in a way in which we have some advantage. The general industry of the country, being always in proportion to the capital which employs it, will not thereby be diminished ... but only left to find out the way in which it can be employed with the greatest advantage."[11]

Writing several decades after Smith in 1808, Robert Torrens articulated a preliminary definition of comparative advantage as the loss from the closing of trade:

"[I]f I wish to know the extent of the advantage, which arises to England, from her giving France a hundred pounds of broad cloth, in exchange for a hundred pounds of lace, I take the quantity of lace which she has acquired by this transaction, and compare it with the quantity which she might, at the same expense of labour and capital, have acquired by manufacturing it at home. The lace that remains, beyond what the labour and capital employed on the cloth, might have fabricated at home, is the amount of the advantage which England derives from the exchange."[12]

In 1817, David Ricardo published what has since become known as the theory of comparative advantage in his book On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.

Ricardo's Example

In a famous example, Ricardo considers a world economy consisting of two countries, Portugal and England, which produce two goods of identical quality. In Portugal, the a priori more efficient country, it is possible to produce wine and cloth with less labor than it would take to produce the same quantities in England. However, the relative costs of producing those two goods differ between the countries.

| Hours of work necessary to produce one unit | ||

|---|---|---|

| Country | Cloth | Wine |

| England | 100 | 120 |

| Portugal | 90 | 80 |

First, Ricardo considers the case in which countries do not trade with each other. Without trade, England needs to spend 220 hours of work to produce one unit of cloth and one unit of wine. Portugal requires 170 hours of work to produce the same quantities.

Under free trade, England specializes in cloth and Portugal in wine. In particular, England spends 220 labor hours to produce 2.2 units of cloth while Portugual spends 170 hours to produce 2.125 units of wine. Global production of both goods will have increased. Provided that the countries can trade a unit of cloth for between .833 and 1.125 units of wine, each country can consume more wine and cloth under free trade than in autarky.

The Ricardian Model

The following is a typical modern interpretation of the classical Ricardian model.[13] In the interest of simplicity, it uses notation and definitions, such as opportunity cost, unavailable to Ricardo.

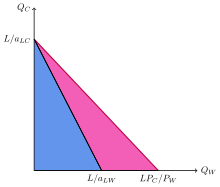

The world economy consists of two countries, Home and Foreign, which produce wine and cloth. Labor, the only factor of production, is mobile domestically but not internationally; there may be migration between sectors but not between countries. We denote the labor force in Home by , the amount of labor required to produce one unit of wine in Home by , and the amount of labor required to produce one unit of cloth in Home by . The total amount of wine and cloth produced in Home are and respectively. We denote the same variables for Foreign by appending a prime. For instance, is the amount of labor needed to produce a unit of wine in Foreign.

We don't know if Home is more productive than Foreign in making cloth. That is, if . Similarly, we don't know if Home has an absolute advantage in wine. However, we will assume that Home is more relatively productive in cloth than Foreign:

Equivalently, we may assume that Home has a comparative advantage in cloth in the sense that it has a lower opportunity cost for cloth in terms of wine than Foreign:

In the absence of trade, the relative price of cloth and wine in each country is determined solely by the relative labor cost of the goods. Hence the relative autarky price of cloth is in Home and in Foreign. With free trade, the price of cloth or wine in either country is the world price or.

Instead of considering the world demand (or supply) for cloth and wine, we are interested in the world relative demand (or relative supply) for cloth and wine, which we define as the ratio of the world demand (or supply) for cloth to the world demand (or supply) for wine. In general equilibrium, the world relative price will be determined uniquely by the intersection of world relative demand and world relative supply curves.

We assume that the relative demand curve reflects substitution effects and is decreasing with respect to relative price. The behavior of the relative supply curve, however, warrants closer study. Recalling our original assumption that Home has a comparative advantage in cloth, we consider five possible intervals:

- If , then Foreign specializes in wine, for the wage in the wine sector is greater than the wage in the cloth sector. However, Home workers are indifferent between working in either sector. Consequently, the quantity supplied can take any value.

- If , then both Home and Foreign specialize in wine, for similar reasons as above, and so the quantity supplied is zero.

- If , then Home specializes in cloth whereas Foreign specializes in wine. The quantity supplied is given by the ratio of the world production of cloth to the world production of wine.

- If , then both Home and Foreign specialize in cloth. The quantity supplied tends to infinity as the quantity of wine supplied approaches zero.

- If , then Home specializes in cloth while Foreign workers are indifferent between sectors. Again, the relative quantity supplied can take any value.

The relative price is thus always bounded by the inequality

In autarky, Home faces a production constraint of the form

from which it follows that Home's cloth consumption at the production possibilities frontier is

- .

With free trade, Home produces cloth exclusively, an amount of which it exports in exchange for wine at the prevailing rate. Thus Home's overall consumption is now subject to the constraint

while its its cloth consumption at the consumption possibilities frontier is given by

- .

A symmetric argument holds for Foreign. Therefore, by trading and specializing in a good for which it has a comparative advantage, each country can expand its consumption possibilities. Consumers can choose from bundles of wine and cloth that they could not have produced themselves in closed economies.

Modern theories

This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. (November 2012) |

Classical comparative advantage theory was extended in two directions: Ricardian theory (Gottfried Haberler's work reformulating the ideas based on the principles of opportunity cost) and Heckscher–Ohlin–Samuelson theory (HOS theory). Ricardian theory, which is usually illustrated using the Ricardian model, highlights the international differences labor productivity in explaining international trade patterns.

Using the example below, a worker from Germany is relatively more productive at producing shoes compared to a worker in China. The Ricardian model predicts that Germany exports shoes to China and import shirts from China. In contrast the Heckscher–Ohlin–Samuelson theory of comparative advantage highlights the international differences in relative abundances of resource in explaining pattern of trade. For example if Germany has a higher capital per labor ratio compared to China, and that shoe production is relatively more capital-intensive than shirt production (producing one pair of shoes requires more capital per labor compared to producing one unit of shirt), the HOS theorem predicts that Germany exports shoe to China and import shirts from China.

| Shirts | Shoes | |

|---|---|---|

| Germany | 8 | 8 |

| China | 4 | 2 |

In both Ricardian and HOS models, the comparative advantage concept is formulated for 2 country, 2 commodity case. It can easily be extended to the 2 country, many commodity case or many country, 2 commodity case.[14][15] But in the case with many countries (more than 3 countries) and many commodities (more than 3 commodities), the notion of comparative advantage loses its facile features and requires totally different formulation.[16] In these general cases, HOS theory totally depends on Arrow-Debreu type general equilibrium theory but gives little information other than general contents. Ricardian theory was formulated in Jones' 1961 paper,[17] but it was limited to the case where there are no traded intermediate goods. In view of growing outsourcing and global procuring, it is necessary to extend the theory to the case with traded intermediate goods. This was done in Shiozawa's 2007 paper.[18][19] Until now, this is the unique general theory which accounts for traded input goods.

Evidence of effects on the economy

Comparative advantage is a theory about the benefits that specialization and trade would bring, rather than a strict prediction about actual behavior. (In practice, governments restrict international trade for a variety of reasons, e.g. North Korea's ideological adherence to Juche.) Nonetheless there is a large amount of empirical work testing the predictions of comparative advantage. The empirical works usually involve testing predictions of a particular model. For example the Ricardian model predicts that technological differences in countries results in differences in labor productivity. The differences in labor productivity in turn determines the comparative advantages across different countries. Testing the Ricardian model for instance involves looking at relationship between relative labor productivity and international trade patterns. A country that is relatively efficient in producing shoes tends to export shoes.

Early Tests

Two of the first tests of comparative advantage were by MacDougall (1951, 1952).[20][21] A prediction of a two-country Ricardian comparative advantage model is that countries will export goods where output per worker (i.e. productivity) is higher. That is, we expect a positive relationship between output per worker and number of exports. MacDougall tested this relationship with data from the US and UK, and did indeed find a positive relationship. The statistical test of this positive relationship was replicated[22][23] with new data by Stern (1962) and Balassa (1963).

More recent evidence

Dosi et al (1988)[24] conduct a book-length empirical examination that suggests that international trade in manufactured goods is largely driven by differences in national technological competencies.

One critique of the textbook model of comparative advantage is that there are only two goods. The results of the model are robust to this assumption. Dornbusch et al (1977)[25] generalized the theory to allow for such a large number of goods as to form a smooth continuum. Based in part on these generalizations of the model, Davis (1995)[26] provides a more recent view of the Ricardian approach to explain trade between countries with similar resources.

More recently, Golub and Hsieh (2000)[27] presents modern statistical analysis of the relationship between relative productivity and trade patterns, which finds reasonably strong correlations, and Nunn (2007)[28] finds that countries that have greater enforcement of contracts specialize in goods that require relationship-specific investments.

Taking a broader perspective, there has been work about the benefits of international trade. Zimring & Etkes(2014)[29] finds that the Blockade of the Gaza Strip, which substantially restricted the availability of imports to Gaza, saw labor productivity fall by 20% in three years. Markusen et al (1994)[30] reports the effects of moving away from autarky to free trade during the Meiji Restoration, with the result that national income increased by up to 65% in 15 years.

Considerations

Development economics

The theory of comparative advantage, and the corollary that nations should specialize, is criticized on pragmatic grounds within the import substitution industrialization theory of development economics, on empirical grounds by the Singer–Prebisch thesis which states that terms of trade between primary producers and manufactured goods deteriorate over time, and on theoretical grounds of infant industry and Keynesian economics. In older economic terms, comparative advantage has been opposed by mercantilism and economic nationalism. These argue instead that while a country may initially be comparatively disadvantaged in a given industry (such as Japanese cars in the 1950s), countries should shelter and invest in industries until they become globally competitive. Further, they argue that comparative advantage, as stated, is a static theory – it does not account for the possibility of advantage changing through investment or economic development, and thus does not provide guidance for long-term economic development.

Much has been written since Ricardo as commerce has evolved and cross-border trade has become more complicated. Today trade policy tends to focus more on "competitive advantage" as opposed to "comparative advantage". One of the most indepth research undertakings on "competitive advantage" was conducted in the 1980s as part of the Reagan administration's Project Socrates to establish the foundation for a technology-based competitive strategy development system that could be used for guiding international trade policy.

Free mobility of capital in a globalized world

Ricardo explicitly bases his argument on an assumed immobility of capital: " ... if capital freely flowed towards those countries where it could be most profitably employed, there could be no difference in the rate of profit, and no other difference in the real or labor price of commodities, than the additional quantity of labor required to convey them to the various markets where they were to be sold."[31]

He explains why, from his point of view (anno 1817), this is a reasonable assumption: "Experience, however, shows, that the fancied or real insecurity of capital, when not under the immediate control of its owner, together with the natural disinclination which every man has to quit the country of his birth and connexions, and entrust himself with all his habits fixed, to a strange government and new laws, checks the emigration of capital."[31]

Criticism

Several arguments have been advanced against using comparative advantage as a justification for advocating free trade, and they have gained an audience among economists. For example, James Brander and Barbara Spencer demonstrated how, in a strategic setting where a few firms compete for the world market, export subsidies and import restrictions can keep foreign firms from competing with national firms, increasing welfare in the country implementing these so-called strategic trade policies.[32]

However, the overwhelming consensus of the economics profession remains that while these arguments are theoretically valid under certain assumptions, these assumptions do not usually hold and should not be used to guide trade policy.[33] Gregory Mankiw, chairman of the Harvard Economics Department, has said ″Few propositions command as much consensus among professional economists as that open world trade increases economic growth and raises living standards.″[34]

See also

- Competitive advantage

- Revealed comparative advantage

- Heckscher-Ohlin model

- Bureau of Labor Statistics

- Resource curse

Notes

- ^ Maneschi, Andrea (1998). Comparative Advantage in International Trade: A Historical Perspective. Cheltenham: Elgar. p. 1.

- ^ "BLS Information". Glossary. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Information Services. February 28, 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ Dixit, Avinash; Norman, Victor (1980). Theory of International Trade: A Dual, General Equilibrium Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 2.

- ^ Baumol, William J. and Alan S. Binder, 'Economics: Principles and Policy, [p. 50 http://books.google.com/books?id=6Kedl8ZTTe0C&lpg=PA49&dq=%22law%20of%20comparative%20advantage%22&pg=PA50#v=onepage&q=%22law%20of%20comparative%20advantage%22&f]

- ^ O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003) [January 2002]. Economics: Principles in Action. The Wall Street Journal:Classroom Edition (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall: Addison Wesley Longman. p. 444. ISBN 0-13-063085-3. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Steven M Suranovic (2010). "International Trade Theory and Policy".

- ^ Krugman, Paul (1996). "Ricardo's Difficult Idea". Retrieved 2014-08-09.

- ^ Maneschi, Andrea (1998). Comparative Advantage in International Trade: A Historical Perspective. Cheltenham: Elgar. pp. 6–13.

- ^ Deardorff, Alan (Oct. 1980). "The General Validity of the Law of Comparative Advantage". Journal of Political Economy. 88 (5): 941–957.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Dixit, Avinash; Norman, Victor (1980). Theory of International Trade: A Dual, General Equilibrium Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 93–126.

- ^ Smith, Adam (1776). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1904 ed.). London: Library of Economics and Liberty. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ^ Torrens, Lionel (1808). The Economists Refuted and Other Early Economic Writings (1984 ed.). New York: Kelley. p. 37.

- ^ Krugman, Paul; Obstfeld, Maurice (1988). International Economics: Theory and Policy (2008 ed.). New York: Prentice Hall. pp. 27–36.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite jstor}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by jstor:1828066, please use {{cite journal}} with

|jstor=1828066instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.2307/1885496, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.2307/1885496instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1467-9396.2005.00552.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1467-9396.2005.00552.xinstead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.2307/2295945, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.2307/2295945instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.14441/eier.3.141, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.14441/eier.3.141instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/13504851.2011.617871, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/13504851.2011.617871instead. - ^ MacDougall, G. D. A. (1951). "British and American exports: A study suggested by the theory of comparative costs. Part I.". The Economic Journal. Vol. 61(244). pp. 697–724.

- ^ MacDougall, G. D. A. (1952). "British and American exports: A study suggested by the theory of comparative costs. Part II". The Economic Journal. Vol. 62(247). pp. 487–521.

- ^ Stern, Robert M. (1962). "British and American productivity and comparative costs in international trade". Oxford Economic Papers. pp. 275–296.

- ^ Balassa, Bela. (1963). "An empirical demonstration of classical comparative cost theory". The Review of Economics and Statistics. pp. 231–238.

- ^ Dosi, G., Pavitt, K, & L. Soete (1988). The Economics of Technical Change and International Trade. Brighton: Wheatsheaf.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dornbusch, R., Fischer, S. & P. Samuelson (1977). "Comparative Advantage, Trade and Payments in a Ricardian Model with a Continuum of Goods". American Economic Review. Vol. 67. pp. 823–839.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Davis, D. (1995). "Intraindustry Trade: A Heckscher-Ohlin-Ricardo Approach". Journal of International Economics. Vol. 39. pp. 201–226.

- ^ Golub, S. & C-T Hsieh (2000). "Classical Ricardian Theory of Comparative Advantage Revisited". Review of International Economics. Vol. 8(2). pp. 221–234.

- ^ Nunn, N (2007). "Relationship-Specificity, Incomplete Contracts, and the Pattern of Trade". Quarterly Journal of Economics. Vol. 122(2). pp. 569–600.

- ^ Zimring, A. & Etkes, H. (2014) "When Trade Stops: Lessons from the 2007-2010 Gaza Blockade". Journal of International Economics, forthcoming.

- ^ Markusen, J.R., Melvin J.R., Kaempfer, W.M., & K. Maskus (1994). International Trade: Theory and Evidence (PDF). McGraw-Hill. p. 218. ISBN 978-0070404472. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ricardo (1817). On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. London, Chapter 7

- ^ Krugman, Paul R. (1987). "Is Free Trade Passe?". Journal of Economic Perspectives. Vol. 1(2). pp. 131–144.

- ^ Irwin, Douglas. (1991). "Retrospectives: Challenges to Free Trade". Journal of Economic Perspectives. Vol. 5(2). pp. 201–208.

- ^ Mankiw, N.G. "Outsourcing Redux".

References

- Boudreaux, Donald J. (2008). "Comparative Advantage". In David R. Henderson (ed.) (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Markusen, Melvin, Kaempfer and Maskus, " International Trade: Theory and Evidence"

- Ronald Findlay (1987). "comparative advantage," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 1, pp. 514–17.

- Hardwick, Khan and Langmead (1990). An Introduction to Modern Economics - 3rd Edn

- A. O'Sullivan & S.M. Sheffrin (2003). Economics. Principles & Tools.

External links

- Comparative advantage in glossary, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Information Services

- David Ricardo's The Principles of Trade and Taxation (original source text)

- Ricardo's Difficult Idea, Paul Krugman's exploration of why non-economists don't understand the idea of comparative advantage

- The Ricardian Model of Comparative Advantage

- J.G. Hülsmann's Capital Exports and Free Trade explanation of why the immobility of capital is not an essential condition.

- Matt Ridley, 'When Ideas Have Sex', a talk at TED in which he explains comparative advantage for a general audience (5:05 out in the video).