Operation Cobra: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

=== Breakout and advance 28–31 July === |

=== Breakout and advance 28–31 July === |

||

By 28 July the German defenses across the US front had largely collapsed under the full weight of VII and VIII Corps' advance, and resistance was disorganised and patchy.<ref name=Hastings258 /> VIII Corps' [[4th Armored Division (United States)|4th Armored Division]], entering combat for the first time, captured Coutances but met stiff opposition east of the town,<ref name=Hastings258 /> and US units penetrating into the depth of the German positions were variously counterattacked by elements of the [[2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich|2nd SS Panzer (Das Reich)]], [[17th SS Panzergrenadier Division Götz von Berlichingen|17th SS Panzergrenadier]], and 353rd Infantry Divisions, all seeking to escape entrapment.<ref name=Hastings260>Hastings, p. 260</ref> A desperate counterattack was mounted against the |

By 28 July the German defenses across the US front had largely collapsed under the full weight of VII and VIII Corps' advance, and resistance was disorganised and patchy.<ref name=Hastings258 /> VIII Corps' [[4th Armored Division (United States)|4th Armored Division]], entering combat for the first time, captured Coutances but met stiff opposition east of the town,<ref name=Hastings258 /> and US units penetrating into the depth of the German positions were variously counterattacked by elements of the [[2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich|2nd SS Panzer (Das Reich)]], [[17th SS Panzergrenadier Division Götz von Berlichingen|17th SS Panzergrenadier]], and 353rd Infantry Divisions, all seeking to escape entrapment.<ref name=Hastings260>Hastings, p. 260</ref> A desperate counterattack was mounted against the 2nd Armored Division by German remnants, but this was a disaster and the Germans abandoned their vehicles and fled on foot.<ref name=Hastings260 /> An exhausted and demoralized Bayerlein reported that his Panzer Lehr Division was "finally annihilated", with its armor wiped out, its personnel either casualties or missing, and all headquarters records lost.<ref name=Williams185 /> |

||

[[Image:Coutances.jpg|thumb|right|US [[Stuart tank|M5A1 Stuart]] tank of the 4th Armored Division (VIII Corps) in Coutances]]Meanwhile Marshal von Kluge, commanding all German forces on the [[Western Front (World War II)|Western Front]] (''[[OB West|Oberbefehlshaber West]]''), was mustering reinforcements, and elements of the [[2nd Panzer Division (Germany)|2nd]] and [[116th Panzer Division (Germany)|116th]] Panzer Divisions were approaching the battlefield. The US XIX Corps, led by Major General [[Charles H. Corlett]], entered the battle on 28 July on the left of VII Corps, and between 28 and 31 July became embroiled with these reinforcements in what would be the fiercest fighting since Cobra began.<ref>Hastings, p. 261</ref> When ordered to concentrate his division, Colonel [[Heinz Günther Guderian]], 116th Division's senior staff officer, was frustrated by the high level of Allied fighter-bomber activity.<ref name=Hastings262 /> Without receiving direct support from 2nd Panzer as promised, Guderian stated that his panzergrenadiers could not successfully counterattack the Americans.<ref>Hastings, p. 263</ref> |

[[Image:Coutances.jpg|thumb|right|US [[Stuart tank|M5A1 Stuart]] tank of the 4th Armored Division (VIII Corps) in Coutances]]Meanwhile Marshal von Kluge, commanding all German forces on the [[Western Front (World War II)|Western Front]] (''[[OB West|Oberbefehlshaber West]]''), was mustering reinforcements, and elements of the [[2nd Panzer Division (Germany)|2nd]] and [[116th Panzer Division (Germany)|116th]] Panzer Divisions were approaching the battlefield. The US XIX Corps, led by Major General [[Charles H. Corlett]], entered the battle on 28 July on the left of VII Corps, and between 28 and 31 July became embroiled with these reinforcements in what would be the fiercest fighting since Cobra began.<ref>Hastings, p. 261</ref> When ordered to concentrate his division, Colonel [[Heinz Günther Guderian]], 116th Division's senior staff officer, was frustrated by the high level of Allied fighter-bomber activity.<ref name=Hastings262 /> Without receiving direct support from 2nd Panzer as promised, Guderian stated that his panzergrenadiers could not successfully counterattack the Americans.<ref>Hastings, p. 263</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:11, 28 October 2009

| Operation Cobra | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Overlord (the Battle of Normandy) | |||||||

M4 and M4A3 Sherman tanks and infantrymen of the US 4th Armored Division in Coutances | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

8 infantry divisions,[3] 3 armored divisions[3] 2,451 Tanks and Tankdestroyer[4] [5][6] |

2 infantry divisions,[3] 1 Parachute division,[3] 4 Panzer Divisions,[3] 1 Panzergrenadier Division[3] 190 Tanks and Stug [5][6] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,800 Casualties[nb 1] | unknown | ||||||

Template:FixBunching Operation Cobra was the codename for an offensive launched by the First United States Army eight weeks after the D-Day landings, during the Normandy Campaign of World War II. American Lieutenant General Omar Bradley's intention was to take advantage of the German preoccupation with British and Canadian activity around the town of Caen, and punch through the German defenses penning in his troops while his opponent was distracted and unbalanced. Once a corridor had been created, the First Army would then be able to advance into Brittany, rolling up the German flanks and freeing itself of the constraints imposed by operating in the Norman bocage countryside. After a slow start the offensive gathered momentum, and German resistance collapsed as scattered remnants of broken units fought to escape to the Seine. Lacking the resources to cope with the situation, the German response was ineffectual, and the entire Normandy front soon collapsed. Operation Cobra, together with concurrent offensives by the Second British and First Canadian Armies, was decisive in securing an Allied victory in the Normandy Campaign.

Having been delayed several times by poor weather, Operation Cobra commenced on 25 July with a concentrated aerial bombardment from thousands of Allied aircraft. Supporting offensives launched by the British and Canadians had drawn the bulk of German armored reserves away from the American sector, and coupled with the general lack of men and materiel available to the Germans, it was impossible for them to form successive lines of defense. Units of VII Corps led the initial two-division assault while other First Army corps mounted supporting attacks designed to pin German units in place. Progress was slow on the first day, but opposition started to crumble once the thin defensive crust had been broken. By 27 July most organized resistance had been overcome, and VII and VIII Corps were advancing rapidly, isolating the Cotentin peninsula.

By 31 July, XIX Corps had destroyed the last forces opposing the First Army, and Bradley's troops were finally freed from the bocage. Reinforcements were moved west by Marshal Günther von Kluge and employed in various counterattacks, the largest of which (codenamed Operation Lüttich) was launched on 7 August between Mortain and Avranches. Although this led to the bloodiest phase of the battle, it was mounted by already exhausted and understrength units and had little effect other than to further deplete von Kluge's forces. On 8 August, troops of the newly activated Third United States Army captured the city of Le Mans, formerly the German Seventh Army's headquarters. Operation Cobra transformed the high-intensity infantry combat of Normandy into rapid maneuver warfare, and led to the creation of the Falaise pocket and the loss of the German position in northwestern France.

Background

Following the successful Allied Invasion of Normandy on 6 June 1944, progress inland was slow. To facilitate the Allied build-up in France and to secure room for further expansion, the deep water port of Cherbourg on the western flank of the American sector and the historic town of Caen in the British and Canadian sector to the east represented early objectives.[9] The original plan for the Normandy campaign envisioned strong offensive efforts in both sectors, in which Lieutenant-General Sir Miles Dempsey's British Second Army would secure Caen and the area south of it,[10] and Lieutenant General Omar Bradley's United States First Army would "wheel round" to the Loire.[11]

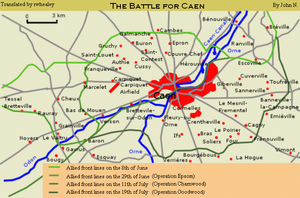

General Bernard Montgomery, commanding all Allied ground forces in Normandy, intended Caen to be taken on D-Day, while Cherbourg was expected to fall fifteen days later.[12] Second Army was to seize Caen and then form a front to the south-east, extending to Caumont-l'Éventé, to acquire airfields and protect First Army's left flank while it moved on Cherbourg.[13] Possession of Caen and its surroundings—desirable for open terrain that would permit maneuver warfare[14]—would also give Second Army a suitable staging area for a push south to capture Falaise, which could be used as the pivot for a swing right to advance on Argentan and then towards the Touques River.[15] Caen's capture has been described by historian L. F. Ellis as the most important D-Day objective assigned to Lieutenant-General Crockers's I Corps. However, both Ellis and Chester Wilmot characterize the Allied plan as "ambitious";[nb 2] the Caen sector contained the strongest defences in Normandy.[18]

The initial attempt by I Corps to reach the city on D-Day was blocked by elements of the 21st Panzer Division, and with the Germans committing to the city's defense most of the reinforcements sent to meet the invasion,[nb 3] the Anglo-Canadian front rapidly congealed short of Second Army's objectives.[19] Operation Perch in the week following D-Day, and Operation Epsom (26–30 June) brought some territorial gains and depleted its defenders, but Caen remained in German hands until Operation Charnwood (7–9 July), when the Second Army managed to take the northern part of the city up to the River Orne in a frontal assault.[18][20]

The successive Anglo-Canadian offensives around Caen were drawing the best of the German forces in Normandy, including most of the available armour, to the eastern end of the Allied lodgement.[18] Even so, the United States First Army was struggling to make progress against dogged German resistance. In part, operations were slow due to the constraints of the bocage landscape of densely-packed banked hedgerows, sunken lanes, and small woods, for which US units had not trained.[21] Furthermore, with no port facilities in Allied hands all reinforcement and resupply had to take place over the beaches and was at the mercy of the weather.[22] On 19 June a severe storm descended on the English Channel, lasting for three days and causing significant delays to the Allied build-up and the cancellation of some planned operations.[23] First Army's attempt to press forward in the western sector was eventually halted by Bradley before the town of Saint-Lô,[24] in order to prioritize operations directed at the seizure of Cherbourg.[25] Cherbourg's defenders were not set up for robust performance, consisting largely of four battlegroups formed from the remnants of units that had retreated up the Cotentin peninsula; the port's defences had been designed principally to meet an attack from the sea.[26] However, organized German resistance ended only on 27 June, when the 9th American Infantry Division managed to reduce the defences of Cap-de-la-Hague to the north-west of the city.[27] Within four days Major General J. Lawton "Lightning Joe" Collins's VII Corps resumed the offensive towards Saint-Lô, alongside XIX Corps and VIII Corps,[28] causing the Germans to move additional armor into the US sector.[28]

Planning

According to Montgomery's official biographer, the foundation of Operation Cobra was laid on 13 June.[29][30] Montgomery's plan at that time called for Bradley's First Army to take Saint-Lô and Coutances and then make two southward thrusts; one from Caumont towards Vire and Mortain, and the other from Saint-Lô towards Villedieu and Avranches. Although pressure was to be kept up along the Cotentin Peninsula towards La Haye-du-Puits and Valognes, the capture of Cherbourg was not an immediate priority.[29] However, with Cherbourg's seizure by Collins' VII Corps on 27 June Montgomery's initial timetable was soon outdated[25] and the thrust from Caumont was never adopted.[31]

Following the conclusion of Operation Charnwood and the cancellation of First Army's offensive towards Saint-Lô,[32][33] Montgomery met with Bradley and Dempsey on 10 July to discuss 21st Army Group's next move.[34] During the meeting Bradley admitted that progress on the western flank was very slow.[24][nb 4] However, he had been working on plans for a breakout attempt, codenamed Operation Cobra, to be launched by the First Army on 18 July.[37][38][39][40][41][42] He presented his ideas to Montgomery,[35] who approved, and the directive that emerged from the meeting made it clear that the overall strategy over the coming days would be to draw enemy attention away from the First Army to the British and Canadian sector;[24] Dempsey was instructed to "go on hitting: drawing the German strength, especially the armour, onto yourself - so as to ease the way for Brad[ley]".[34] To accomplish this, Operation Goodwood was planned,[43] and Eisenhower ensured that both operations would have the support of the Allied air forces with their strategic bombers.[24]

On 12 July, Bradley briefed his subordinate commanders on the Cobra plan, which consisted of three phases. The main effort would be under the control of Collins' VII Corps. In the first phase, the breakthrough attack would be conducted by Major General Eddy's 9th and Major General Hobbs' 30th infantry divisions, which would punch a hole in the German tactical zone and then hold the flanks of the penetration while Major General Huebner's 1st Infantry and Major General Brooks' 2nd Armored divisions pushed into the depth of the position until resistance collapsed.[44] During the second phase, an exploitation force of 5–6 divisions would pass through the opening created in the German defenses and swing west.[45] If these two phases were successful the western German position would become untenable, and the third phase would permit a relatively easy advance to the southwest end of the bocage to cut off and seize the Brittany peninsula.[45][46] First Army's intelligence estimated that no German counterattack would occur in the first few days after Cobra's launch, and that if attacks materialized after that date, they would consist of no more than battalion-sized operations.[47]

Cobra was to be a concentrated attack on a 7,000-yard (6,400 m) front, unlike previous American 'broad front' offensives,[48] and would have heavy air support.[48] Fighter-bombers would concentrate on hitting forward German defenses in a 250-yard (230 m) belt immediately south of the Saint-Lô–Periers road, while General Spaatz's heavy bombers would bomb to a depth of 2,500 yards (2,300 m) behind the German main line of resistance.[49] It was anticipated that the physical destruction and shock value of a short, intense preliminary bombardment would greatly weaken the German defense,[48] so in addition to divisional artillery, Army- and Corps-level units would provide support, including nine heavy, five medium, and seven light artillery battalions.[50] Over one thousand tubes of divisional and corps artillery were committed to the offensive,[50] and approximately 140,000 artillery rounds were allocated to the operation in VII Corps alone, with another 27,000 for VIII Corps.[51] [52]

In an attempt to overcome the mobility constraints of the bocage that had made offensive operations so difficult and costly for both sides, "Rhino" modifications were made to some M4 Sherman and M5A1 Stuart tanks, and M10 tank destroyers, by fitting them with hedge-breaching 'tusks' that were capable of forcing a path through the Norman hedgerows.[44] While German tanks remained restricted to the roads, US armor would now be able to maneuver more freely,[44] although in practice these devices were not as effective as often believed.[53] However, by the eve of Cobra sixty percent of First Army's tanks were so equipped.[54] To preserve operational security, Bradley forbade their use until Cobra was launched. [55] In all 1,269 M4 medium tanks, 694 M5A1 light tanks, and 288 M10 tank destroyers were available.[56]

Operations Goodwood and Atlantic

On 18 July the British VIII and I Corps, to the east of Caen, launched Operation Goodwood. The offensive began with the largest air bombardment in support of ground forces yet, with more than a thousand aircraft dropping 6,000 tons of high explosive and fragmentation bombs from low altitude.[57] German positions to the east of Caen were shelled by 400 artillery pieces, and many villages were reduced to rubble,[57] but German artillery further to the south, on the Bourguébus Ridge, was outside the range of the British artillery,[58] and the defenders of Cagny and Emieville were largely unscathed by the bombardment.[59] This contributed to the losses suffered by Second Army, which sustained over 4,800 casualties.[nb 5] Principally an armored offensive, between 250 and 400 British tanks were put out of action,[nb 6] although recent examination suggests that only 140 were completely destroyed with an additional 174 damaged.[63] The operation remains the largest tank battle ever fought by the British Army,[64] and resulted in the expansion of the Orne bridgehead and the final capture of Caen.[20]

Simultaneously, II Canadian Corps on Goodwood's western flank launched Operation Atlantic. Intended to strengthen the Allied foothold along the banks of the Orne River, and take Verrières Ridge to the south of Caen,[65] Atlantic made initial gains but ran out of steam as casualties mounted.[5] A counterstroke by two SS Panzer Divisions pushed the Canadians back past their start lines, and II Canadian Corps's commander, Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds, had to commit reinforcements to stabilize the front.[65] Atlantic cost the Canadians 1,349[66] casualties and failed to take Verrières Ridge, but in conjunction with Goodwood caused the Germans to commit most of their armor and additional reinforcements to the British and Canadian sector.[5] Only two Panzer Divisions with 190 tanks now faced Bradley's First Army,[5][6] while seven Panzer divisions with 750 tanks were positioned in the Caen area,[6] far away from where Operation Cobra would be launched.[5]

Allied offensive

Preliminary attacks

To gain good terrain for Operation Cobra, Bradley and Collins conceived a plan to push forward to the Saint-Lô–Periers road, along which VII and VIII Corps were securing jumping-off positions.[29] On 18 July, at a cost of 5,000 casualties, the American 29th and 35th Infantry Divisions managed to gain the vital heights of Saint-Lô, driving back General der Fallschirmtruppen Eugen Meindl's II Parachute Corps.[29] Meindl's paratroopers, together with the 352nd Infantry Division (which had been in action since its D-Day defense of Omaha Beach) were now in ruins, and the stage for the main offensive was set.[29] Due to poor weather conditions that had also been hampering Goodwood and Atlantic, Bradley decided to postpone Cobra for a few days—a decision that worried Montgomery, as the British and Canadian operations had been launched to support a break-out attempt that was failing to materialize.[67][68] By 24 July the skies had cleared enough for the start order to be given, and 1,600 Allied aircraft took off for Normandy.[67] However, the weather closed in again over the battlefield, and under poor visibility conditions, more than 25 Americans were killed and 130 wounded in the bombing—some enraged soldiers opened fire on their own aircraft, a not uncommon practice in Normandy when suffering from friendly fire.[67]

Main attack and breakthrough 25–27 July

Cobra got underway on 25 July at 09:38, when around 600 Allied fighter-bombers attacked strongpoints and enemy artillery along a 300-yard (270 m) wide strip of ground located in the St. Lô area.[69] During the next hour, 1,800 heavy bombers of the US Eighth Air Force saturated an area 6,000 yards (5,500 m) wide and 2,200 yards (2,000 m) deep on the Saint-Lô–Periers road, succeeded by a third and final wave of medium bombers.[70] Approximately 3,000 US aircraft had carpet-bombed a narrow section of the front, with the Panzer-Lehr Division taking the brunt of the attack.[71] However, once again not all the casualties were German; Bradley had specifically requested that the bombers approach the target from the east, out of the sun and parallel to the Saint-Lô–Periers road, in order to minimize the risk of friendly losses, but most of the airmen instead came in from the north, perpendicular to the front line.[70] Despite efforts by US units to identify their positions, inaccurate bombing by the Eighth Air Force killed 111 men, including Lieutenant-General Lesley McNair—the highest-ranking US soldier to be killed in action in the European Theater of Operations—and wounded 490.[72]

By 11:00 the infantry began to move forward, advancing from crater to crater beyond what had been the German outpost line.[72] Although no serious opposition was forecast,[73] the remnants of Bayerlein's Panzer Lehr consisting of roughly 2,200 men and 45 armoured vehicles,[74] had regrouped and were prepared to meet the advancing US troops, and to the west of Panzer Lehr, the German 5th Parachute Division had escaped the bombing almost intact.[73] Collins' VII Corps were quite disheartened to meet fierce enemy artillery fire,[75] which they expected to have been suppressed by the bombing.[75] Several US units found themselves entangled in fights against strongpoints held by a handful of German tanks, supporting infantry and 88 mm guns[75]—VII Corps gained only 2,200 yards (2,000 m) during the rest of the day.[73] However, if the first day's results had been disappointing, General Collins found cause for encouragement; although the Germans were fiercely holding their positions, these did not seem to form a continuous line and were susceptible to being outflanked or bypassed.[75] Even with prior warning of the American offensive, the British and Canadian actions around Caen had convinced the Germans that the real threat lay there, and tied down their available forces to such an extent that a succession of meticulously prepared defensive positions in depth, as encountered during Goodwood and Atlantic, were not created to meet Cobra.[74] Further unbalancing the German position, Operation Spring, a follow-up to Atlantic conducted by II Canadian Corps, had drawn the 9th SS Panzer Division away from the US sector on the eve of Cobra's launch.[74]

On the morning of 26 July, the US 2nd Armored Division and the veteran 1st Infantry Division joined the attack as planned,[73] reaching one of Cobra's first objectives—a road junction north of Le Mesnil-Herman—the following day.[76] Also on the 26th, Major General Troy H. Middleton's VIII Corps entered the battle, led by the 8th and 90th Infantry Divisions.[77] Despite clear paths of advance through the floods and swamps across their front, both divisions initially disappointed the First Army by failing to gain significant ground,[77] but first light the next morning revealed that the Germans had been compelled to retreat by their crumbling left flank, leaving only immense minefields to delay VIII Corps' advance.[77] By noon on 27 July, 9th Division of VII Corps was also clear of any organized German resistance, and advancing rapidly.[76]

Breakout and advance 28–31 July

By 28 July the German defenses across the US front had largely collapsed under the full weight of VII and VIII Corps' advance, and resistance was disorganised and patchy.[77] VIII Corps' 4th Armored Division, entering combat for the first time, captured Coutances but met stiff opposition east of the town,[77] and US units penetrating into the depth of the German positions were variously counterattacked by elements of the 2nd SS Panzer (Das Reich), 17th SS Panzergrenadier, and 353rd Infantry Divisions, all seeking to escape entrapment.[78] A desperate counterattack was mounted against the 2nd Armored Division by German remnants, but this was a disaster and the Germans abandoned their vehicles and fled on foot.[78] An exhausted and demoralized Bayerlein reported that his Panzer Lehr Division was "finally annihilated", with its armor wiped out, its personnel either casualties or missing, and all headquarters records lost.[47]

Meanwhile Marshal von Kluge, commanding all German forces on the Western Front (Oberbefehlshaber West), was mustering reinforcements, and elements of the 2nd and 116th Panzer Divisions were approaching the battlefield. The US XIX Corps, led by Major General Charles H. Corlett, entered the battle on 28 July on the left of VII Corps, and between 28 and 31 July became embroiled with these reinforcements in what would be the fiercest fighting since Cobra began.[79] When ordered to concentrate his division, Colonel Heinz Günther Guderian, 116th Division's senior staff officer, was frustrated by the high level of Allied fighter-bomber activity.[80] Without receiving direct support from 2nd Panzer as promised, Guderian stated that his panzergrenadiers could not successfully counterattack the Americans.[81]

During the night of 29 July near Saint-Denis-le-Gast, elements of the US 2nd Armored Division found themselves fighting for their lives against a German column from the 2nd SS Panzer and 17th SS Panzergrenadier Divisions, which passed through the American lines in the darkness.[78] Other elements of 2nd Armored were attacked near Cambry and fought for six hours; however, Bradley and his commanders knew that they were currently dominating the battlefield, and such desperate assaults were not a genuine threat to the American position.[78] On 30 July, to protect Cobra's flank and prevent the disengagement and relocation of further German forces, the British VIII Corps launched Operation Bluecoat south from Caumont towards Vire and Mont Pinçon.[82] Advancing southwards along the coast, later that day the US VIII Corps seized the town of Avranches—described by historian Andrew Williams as "the gateway to Brittany and southern Normandy"[47]—and by 31 July XIX Corps had thrown back the last German counterattacks after fierce fighting, inflicting heavy losses in men and tanks.[80] The American advance was now relentless, and the First Army was finally free of the bocage.[47]

Aftermath

At noon on 1 August, the US Third Army was activated under the command of Lieutenant General George S. Patton. Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges assumed command of the First Army, and Bradley was promoted to overall command of both armies, designated 12th Army Group.[83] Patton wrote a poem containing the words:

So let us do real fighting, boring in and gouging, biting. Let's take a chance now that we have the ball. Let's forget those fine firm bases in the dreary shell raked spaces, Let's shoot the works and win![84]

The US advance following Cobra was rapid. By 8 August the city of Le Mans, the former headquarters of the German 7th Army, had fallen to the Americans,[85] and Patton's VIII Corps had swept through Avranches and over the bridge at Pontaubault into Brittany.[86] The German army in Normandy had been reduced to such a poor state by the Allied offensives that, with no prospect of reinforcement in the wake of the Soviet summer offensive against Army Group Centre, very few Germans believed they could now avoid defeat.[87] However, rather than order his remaining forces to withdraw to the Seine, Adolf Hitler sent a directive to von Kluge demanding "an immediate counterattack between Mortain and Avranches"[88] to "annihilate" the enemy and make contact with the west coast of the Cotentin peninsula.[89] Eight of the nine Panzer divisions in Normandy were to be used in the attack, but only four (one of them incomplete) could be relieved from their defensive tasks and assembled in time.[90] German commanders immediately protested that such an operation was impossible given their remaining resources,[89] but these objections were over-ridden and the counter-offensive, codenamed Operation Lüttich, commenced on 7 August around Mortain.[91] The 2nd, 1st SS and 2nd SS Panzer Divisions led the assault, although with only 75 Mk IV and 70 Panther tanks, and 32 self-propelled guns, between them.[92] Hopelessly optimistic, the offensive was essentially over within 24 hours, although fighting continued until 13 August.[93]

With von Kluge's few remaining battleworthy formations destroyed by the First Army, Allied command realised that the entire German position in Normandy was collapsing.[94] Bradley declared: "This is an opportunity that comes to a commander not more than once in a century. We're about to destroy an entire hostile army and go all the way from here to the German border".[94] On 14 August, in conjunction with American movements northwards to Chambois, Canadian forces launched Operation Tractable—the Allied intention was to trap and destroy the entire German Seventh and Fifth Panzer Armies near the town of Falaise.[95] Five days later the two arms of the encirclement were almost complete; the advancing US 90th Infantry Division had made contact with the Polish 1st Armoured Division, and the first Allied units crossed the Seine at Mantes Gassicourt while German units were fleeing eastwards by any means they could find.[96] By 22 August the Falaise Pocket, which the Germans had been fighting desperately to keep open to allow their trapped forces to escape, was finally sealed, effectively ending the Battle of Normandy with a decisive Allied victory.[2] All German forces west of the Allied lines were now dead or in captivity,[97] and although perhaps 100,000 German troops succeeded in escaping they left behind 40,000–50,000 prisoners and over 10,000 dead.[1] A total of 344 tanks and self-propelled guns, 2,447 soft-skinned vehicles and 252 artillery pieces were found abandoned or destroyed in the northern sector of the pocket alone.[98] The Allies were now able to advance freely through undefended territory, and by 25 August all four Allied armies (1st Canadian, 2nd British, 1st US, and 3rd US) involved in the Normandy campaign were on the river Seine.[1]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ Of which 700 were from VIII Corps,[7] and 600 from VII Corps, while the rest are from unknown specific other units.[8]

- ^ "The quick capture of that key city [Caen] and the neighbourhood of Carpiquet was the most ambitious, the most difficult and the most important task of Lieutenant-General J.T. Crocker's I Corps".[16] Wilmot states "The objectives given to Crocker's seaborne divisions were decidedly ambitious, since his troops were to land last, on the most exposed beaches, with the farthest to go, against what was potentially the greatest opposition."[17]

- ^ These included the bulk of the available armored reserves: the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend, and the Panzer Lehr Division.[18]

- ^ By 10 July, Bradley had become concerned enough to write that the Allies faced the possibility of a World War I-type stalemate in the campaign.[35][36]

- ^ I Corps suffered 3,817 casualties and VIII Corps suffered 1,020 casualties.[60]

- ^ Reynolds claims that a careful study of the relevant documents indicate a maximum tank loss of 253 tanks during Goodwood, most of which were repairable,[61] but Buckley claims 21st Army Group lost around 400 tanks during the operation, although he too notes that most were eventually recovered.[62]

- Citations

- ^ a b c Williams, p. 204

- ^ a b Bercuson, p. 232

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Pugsley, p. 47

- ^ Zaloga, p.30

- ^ a b c d e f Hastings, p. 236

- ^ a b c d Jackson, p. 113

- ^ Green, p. 62

- ^ Pugsley, p. 53

- ^ Van der Vat, p. 110

- ^ Bradley, p. 261

- ^ Williams, p. 24

- ^ Williams, p. 38

- ^ Ellis, p. 78

- ^ Greiss, p.308

- ^ Ellis, p. 81

- ^ Ellis, p. 171

- ^ Wilmot, p. 272

- ^ a b c d Keegan, p. 135

- ^ Bercuson, p. 215

- ^ a b Williams, p. 131

- ^ Greiss, p. 317

- ^ Greiss, p. 308–310

- ^ Williams, p. 114

- ^ a b c d Williams, p. 163

- ^ a b Greiss, p. 312

- ^ Hastings, p. 163

- ^ Hastings, p. 165

- ^ a b Greiss, p. 316

- ^ a b c d e Hastings, p. 249

- ^ Williams, p. 126

- ^ Esposito, p.78-80

- ^ Wilmot, p. 351

- ^ Greiss, p. 311

- ^ a b Trew, p. 49

- ^ a b Bradley, p. 272

- ^ Zaloga, p. 7

- ^ Blumenson, p. 187

- ^ Zaloga, p.32

- ^ D'Este, p.338

- ^ Weigley, p.136

- ^ Pogue, p.197

- ^ Williams, p. 175

- ^ Trew, p. 64

- ^ a b c Hastings, p. 252

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 250

- ^ Esposito, pp. 76–77

- ^ a b c d Williams, p. 185

- ^ a b c Hastings, pp. 249–250

- ^ Williams, p. 181

- ^ a b Weigley, p. 151

- ^ Griess, p. 324

- ^ Blumenson, p. 219

- ^ Zaloga, p.3

- ^ Weigley, p.149

- ^ Blumenson, p.207

- ^ Zaloga, p.30

- ^ a b Williams, p. 161

- ^ Williams, p. 165

- ^ Williams, p. 167

- ^ Wilmot, p. 362

- ^ Reynolds, p. 186

- ^ Buckley, p. 36

- ^ Trew, pp. 97–98

- ^ Van-Der-Vat, p. 158

- ^ a b Copp, Approach to Verrières Ridge

- ^ Zuehlke, p. 166

- ^ a b c Hastings, p. 253

- ^ Williams, p. 174

- ^ Williams, p. 180

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 254

- ^ Williams, p. 181

- ^ a b Williams, p. 182

- ^ a b c d Williams, p. 183

- ^ a b c Hastings, p. 256

- ^ a b c d Hastings, p. 255

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 257

- ^ a b c d e Hastings, p. 258

- ^ a b c d Hastings, p. 260

- ^ Hastings, p. 261

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 262

- ^ Hastings, p. 263

- ^ Hastings, p. 265

- ^ Hastings, p. 266

- ^ Williams, p. 186

- ^ Williams, p. 194

- ^ Hastings, p. 280

- ^ Hastings, p. 277

- ^ D'Este, p. 414

- ^ a b Williams, p. 196

- ^ Wilmot, p.401

- ^ Hastings, p. 283

- ^ Hastings, p. 285

- ^ Hastings, p. 286

- ^ a b Williams, p. 197

- ^ Hastings, p. 301

- ^ Williams, p. 203

- ^ Hastings, p. 306

- ^ Hastings, p. 313

References

- Bercuson, David (2004). Maple Leaf Against the Axis. Red Deer Press. ISBN 0-88995-305-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Blumenson, Martin (1961). Breakout and Pursuit. US Government Printing Office.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=and|coauthors=(help) - Bradley, General of the Army Omar N. (1983). A General's Life. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-41023-7.

- Buckley (editor), John (2007). The Normandy Campaign 1944: Sixty Years on. Routledge. ISBN 0-41544-942-1.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Copp, Terry (1 March 1999). "The Approach to Verrières Ridge". Legion Magazine (25). Ottawa: Canvet Publications. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- D'Este, Carlo. Decision in Normandy. Konecky & Konecky. ISBN 1-56852-260-6.

- Ellis, Major L.F.; with Allen R.N., Captain G.R.G. Allen; Warhurst, Lieutenant-Colonel A.E.; Robb, Air Chief-Marshal Sir James (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1962]. Butler, J.R.M (ed.). Victory in the West, Volume I: The Battle of Normandy. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Naval & Military Press Ltd. ISBN 1-84574-058-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Esposito, Brigadier General Vincent (1995). World War II: European Theater. The West Point Atlas of War. Tess Press. ISBN 1-60376-023-7.

- Green, Michael (1999). Patton and the Battle of the Bulge: Operation Cobra and Beyond. MBI. ISBN 0760306524.

- Griess, Thomas (2002). The Second World War: Europe and the Mediterranean; Department of History, United States Military Academy, West Point, New York. SquareOne. ISBN 0-7570-0160-2.

- Hastings, Max (2006). Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy. Vintage Books USA; Reprint edition. ISBN 0-30727-571-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Jackson, G.S. (2006). 8 Corps: Normandy to the Baltic. MLRS Books. ISBN 978-1-905696-25-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Keegan, John (2006). Atlas of World War II. Collins. ISBN 0060890770.

- Pogue, Forrest C. (1954). The Supreme Command. United States Government Printing Office.

- Pugsley, Christopher (2005). Operation Cobra. Battle Zone Normandy. Sutton. ISBN 0750930152.

- Reynolds, Michael (2002). Sons of the Reich: The History of II SS Panzer Corps in Normandy, Arnhem, the Ardennes and on the Eastern Front. Casemate Publishers and Book Distributors. ISBN 0-97117-093-2.

- Trew, Simon (2004). Battle for Caen. Battle Zone Normandy. The History Press Ltd. ISBN 0-75093-010-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Van Der Vat Da, Dan (2003). D-Day; The Greatest Invasion, A People's History. Madison Press Limited. ISBN 1-55192-586-9.

- Weigley, Russell (1981). Eisenhower's Lieutenants. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-13333-5.

- Williams, Andrew (2004). D-Day to Berlin. Hodder. ISBN 0340833971.

- Wilmot, Chester (1997). The Struggle For Europe. Wordsworth Editions Ltd. ISBN 1-85326-677-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Zaloga, Steven J. (2001). Operation Cobra 1944: Breakout from Normandy. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1841762962.

- Zuehlke, Mark (2001). The Canadian Military Atlas. Stoddart. ISBN 0-77373-289-6.

External links

- Normandiememoire.com. "Operation Cobra: the break-out".

- Wiacek, Jacques. "Operation Cobra and final stages of the battle in normandy".