Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science: Difference between revisions

SteveBaker (talk | contribs) →Speed: Lorentz factor...Bugs - please stop guessing. |

|||

| Line 458: | Line 458: | ||

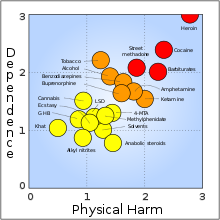

:I don't know who posted that image from the Nutt et al paper, but it should be noted that the diagram is slightly flawed since the addictivity of cocaine doesn't take [[crack cocaine]] into consideration, which is ''possibly'' more psychologically addictive than heroin. Also, the methodology of that study isn't as scientific as one would assume for a Lancet paper. --[[User:Mark PEA|Mark PEA]] ([[User talk:Mark PEA|talk]]) 20:16, 22 January 2010 (UTC) |

:I don't know who posted that image from the Nutt et al paper, but it should be noted that the diagram is slightly flawed since the addictivity of cocaine doesn't take [[crack cocaine]] into consideration, which is ''possibly'' more psychologically addictive than heroin. Also, the methodology of that study isn't as scientific as one would assume for a Lancet paper. --[[User:Mark PEA|Mark PEA]] ([[User talk:Mark PEA|talk]]) 20:16, 22 January 2010 (UTC) |

||

::I have seen a bbc documentary created from the results of that study, and they claimed a difference in effect between crack and powder cocaine could not be established. |

|||

::I grabbed it from our [[Heroin]] article and pasted it there — insert obligatory hectoring to [[WP:BOLD|be bold]] and go fix it or challenge its inclusion in that article, etc. [[User:Comet Tuttle|Comet Tuttle]] ([[User talk:Comet Tuttle|talk]]) 21:20, 22 January 2010 (UTC) |

::I grabbed it from our [[Heroin]] article and pasted it there — insert obligatory hectoring to [[WP:BOLD|be bold]] and go fix it or challenge its inclusion in that article, etc. [[User:Comet Tuttle|Comet Tuttle]] ([[User talk:Comet Tuttle|talk]]) 21:20, 22 January 2010 (UTC) |

||

Revision as of 03:14, 23 January 2010

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

January 19

Circuit Problem

Imagine some resistors set in parallel in a circuit (there may be more elements to the circuit). Kirchoff's law says that, for any path the current might take, it's change in potential must be the same. Why is this true (ie what forces the electrons all to lose the same amount of potential (or energy or wtv))? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 173.179.59.66 (talk) 00:26, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- I'm not sure it is correct to attribute this to a "force". An electron travels through the path of least resistance, so as it loses potential it increases the resistance of the path it took in the conductor, mainly due to heat. This means the next electron behind it won't take exactly the same path, it will take the next best path. This all happens at the speed of light, so when a current is actually flowing through all the parallel resistors it only makes sense that all the electrons lose the same potential. When any one electron has more or less potential then the others around it, it takes a slightly more or less (respectively) "difficult" path in the circuit and then loses more or less potential until it is equal. Otherwise all the current would ravel through the path of absolute least resistance, regardless of how many resistors are in parallel. Sorry my explanation is a little obtuse, maybe someone has a more elagant answer.Vespine (talk) 01:10, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- This sounds a bit like a homework question, so think about what would happen otherwise. If some lost less potential, you'd have electrons gaining potential as they travel through the loop. A 5V battery can't give a potential higher than that, it would be a violation of the conservation of energy. ~ Amory (u • t • c) 01:16, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

Empirical studies of emotion

Is there any scientific or experimental backing to confirm that the words we use to describe emotion are valid and actually reflect objective reality? For example we have common words that describe colours, and these are underpinned by scientific studies of colour in terms of the spectrum and three colour-detecting cells in the human retina. Have any underlying dimensions been experimentally discovered for emotions? Or are we just stuck at the qualitative level? 89.240.50.241 (talk) 00:52, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Have you checked our Emotions article? Mitch Ames (talk) 00:55, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- You can't quantify emotion any more than you can explain how chocolate tastes. There is a thing called internal validity that measures how a term is used by different people at different times. That is to ensure that what you're calling 'anger' isn't a scattershot representation of all sorts of different negative moods. That sort of thing. Vranak (talk) 05:50, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Well we can quantify emotions. I think it is commonly accepted that fear is associated with the fight-or-flight response, which is activated by the sympathetic nervous system; thus we could do a controlled study where adrenaline and its metabolites are measured from samples of blood taken, place it on a graph where subjects report a specific emotion. Look at Graph B on this picture to see what I mean (this is a measure of amphetamine though, not adrenaline).

- If you mean that we can never "know" what a person is feeling, then we are talking about something else known as the problem of other minds. This doesn't mean we can't quantify things, as the OP already mentioned that the colour spectrum is always the same, although we can't "know" what other people are actually seeing (or whether they aren't a philosophical zombie). (Sorry for the scruffy structure of this post, in a hurry) --Mark PEA (talk) 10:46, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- The science on this goes all the way back to Darwin's book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Also very influential is Paul Ekman's work showing that cultures all across the world use very similar facial expressions for basic emotions. Looie496 (talk) 18:08, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

So the answers are No, Yes. 78.151.106.238 (talk) 19:13, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Huh? The answers are yes there is experimental backing (going back to Darwin) that the words we use reflect experimental reality, yes underlying dimensions have been discovered (by Ekman among others), no we aren't just stuck at the qualitative level. For a guide to research on the underlying neural bases of emotion, the books and articles by Joseph LeDoux are a good place to start. Regards, Looie496 (talk) 19:34, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

From what I've read in the Ekman article, it seems that he has only shown that his categories have Social reality, not the underlying physiological mechanisms as with colour and cells in the retina. Money now or belief in witchcraft in the past had similar universal social reality but with no underlying physiological basis. So the answers are still No and Yes, with the possible exception of fear. Believing social reality to be objective truth is what the far right do. 92.29.57.199 (talk) 11:19, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Well, he showed more than that. Social reality would mean, for example, that all members of a given community understand a smile in the same way. What Ekman showed is that isolated cultures from all across the world understand a smile in the same way. That takes us from social reality to biological reality, as I understand it. Certainly Ekman thought that that was what he had done. Looie496 (talk) 17:40, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

People from different cultures believe in witchcraft or money, and neither have an underlying physiological mechanism. As far as I am aware Ekman never demonstrated a physiological mechanism for emotion, as with colour and retinal cells. 92.29.57.199 (talk) 21:34, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

illusion of wheel's direction

how do we get an illusion of a wheel of a car moving in backward direction,when car is at great speed. —Preceding unsigned comment added by Myownid420 (talk • contribs) 02:28, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- See Wagon-wheel effect. Nanonic (talk) 02:37, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Damn, too slow! 218.25.32.210 (talk) 02:37, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- There is an absolutely brilliant depiction of the Wagon-wheel/stroboscopic effect on YouTube.HERE The film/video camera shutter is synchronised with the Helicopter rotors rotation. As a result the main rotor appears stationary as the helicopter flies around. --220.101.28.25 (talk) 10:00, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- In respect to

, it's not that the effect occurs, but rather than the picture actually does reverse -- if we want to demonstrate the illusion, why does it have to make it happen artificially? (For example, This spinning girl illusion works without "cheating.") DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 13:18, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

, it's not that the effect occurs, but rather than the picture actually does reverse -- if we want to demonstrate the illusion, why does it have to make it happen artificially? (For example, This spinning girl illusion works without "cheating.") DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 13:18, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Uh, that's a completely different effect. 17:35, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- In respect to

- There is an absolutely brilliant depiction of the Wagon-wheel/stroboscopic effect on YouTube.HERE The film/video camera shutter is synchronised with the Helicopter rotors rotation. As a result the main rotor appears stationary as the helicopter flies around. --220.101.28.25 (talk) 10:00, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Damn, too slow! 218.25.32.210 (talk) 02:37, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- That image isn't cheating: the whole idea is that the two directions of motion are aliased with the frequency of update in the recording (be it a film or a GIF) and thus are indistinguishable. Given only the final product and no contextual clues, it's impossible to say whether it "actually" reverses or not. --Tardis (talk) 18:46, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Yep - DRosenbach is not understanding the problem. The spinning girl illusion is due to a lack of depth information - the silhouette of a clockwise rotating dancer looks identical to that of an anticlockwise rotation - so your brain can't understand which it is and flips back and forth between representations. The animated GIF is true temporal aliassing - which is a completely different illusion. SteveBaker (talk) 20:14, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- That image isn't cheating: the whole idea is that the two directions of motion are aliased with the frequency of update in the recording (be it a film or a GIF) and thus are indistinguishable. Given only the final product and no contextual clues, it's impossible to say whether it "actually" reverses or not. --Tardis (talk) 18:46, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- In computer graphics, we call this "temporal aliassing".

- The easiest way to think about this is to imagine a wheel with three identical, equally spaced, spokes. In a TV or movie image or computer graphics or something, if the wheel rotates clockwise exactly 120 degrees from one still image to the next then every picture of the wheel would appear to be identical - even though a different one of the spokes would be at the top of the picture each time. Hence, it would not appear to rotate even though it's spinning really fast. However, if the wheel were to rotate only 119 degrees each time then there would be a visual conundrum: Did the wheel rotate 119 degrees clockwise - or one degree anticlockwise? In either case, the resulting series of images would be just the same. Our eyes & brains seem to prefer the slower rotation - so a wheel that's spinning at 119 degrees per frame seems to be rotating slowly backwards. As the wheel slows down, this effect persists - so if it rotates 100 degrees clockwise, our brains will insist that it's rotating 20 degrees anticlockwise...all the way down to 60 degrees. At 60 degrees per frame, we would get the same image whether we rotated 60 degrees forwards or 60 degrees backwards...the image would be identical. Now our poor brains can't figure out what's going on and instead of seeing rotation, we see a kind of flickery 6 spoked wheel! Once you get below 60 degrees per frame, we again have two interpretations - 59 degrees clockwise or 61 degrees anticlockwise. Again, our brains prefer the lower number - so FINALLY, we see what's really going on - a wheel rotating clockwise at 59 degrees per frame.

- The angle below which everything looks normal is therefore exactly half of the spacing of the spokes. If you have a 4 spoked wheel, the anomaly happens when it's spinning at 45 degrees per frame or more...for a 36 spoked wheel, it's only got to be rotating at 5 degrees per frame to look bad. That's why the effect is called the "Wagon wheel effect" - because in the days of early cinema, we had maybe only 24 frames per second - and the stage coach in the cowboy movies that were popular back then only had to rotate fairly slowly to provoke the problem. Wagon wheels have a lot more spokes than most other kinds of wheel! It is probably also the case that filming out in the bright sunny desert where most cowboy movies were made means that the shutter time on the camera had to be kept short - that reduces the effect of motion-blur which greatly enhances the effect. In computer graphics, it takes a lot of effort to simulate motion blur and (in effect) we have an infinitely short "shutter time" - that means that this effect, which had gone largely unnoticed through the era of cars and modern TV cameras is now beginning to show up again.

- What's kinda mind-blowing is that if you merely paint one of the spokes a different color - the illusion more or less vanishes. By breaking the rotational symmetry, the wheel now has to rotate 180 degrees per frame in order to cause this effect - and that's a really fast-moving wheel. We use this technique in computer graphics to try to break the illusion - making all of our wheels asymmetric whenever we can (painting the word "GOODYEAR" in white on the sides of tyres is a good example of that).

- SteveBaker that may be the best RefDesk response ever. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 20:56, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Nah - I forgot to mention the Nyquist limit and the 'half the sampling frequency' thing - which ties in nicely with half of the angle of rotational symmetry. SteveBaker (talk) 02:55, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- SteveBaker that may be the best RefDesk response ever. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 20:56, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- OK...I thought it was an issue of, "if you keep looking at this, it will switch," and that's why I compared it to the spinning/oscillating girl. With my understanding of it, and that's an apparently incorrect understanding as you explain it, my rationale, which is now false, was as follows: If it's only that after a few seconds of watching the little GIF file above that it appears to switch, why does it appear to go in the opposite direction even if one doesn't look at it for the first half of the video. DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 02:42, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Nope - this is something completely different. If my three-spoked wheel example has the wheel rotating at 110 degrees per frame, the backwards 10 degrees per frame that you think you're seeing is a rock-solid effect, you can't keep looking at it and see it 'switch'. The GIF is changing direction because the animation is slowly increasing in speed until it hits the temporal aliasing speed - then, although the speed is still increasing, it appears to slow down, stop and then reverse. You can visualize that in the same way we did with the three-spoked wheel. Imagine a video shot out of the window of a car that's driving along parallel to a really long picket fence with vertical strips every 12 inches. If you drive at 12 inches per frame, the fence seems stationary - if you drive at 11 inches per frame, it seems to be moving backwards - at 6 inches per frame, you see twice the number of fence posts - but kinda flickery - at below 6 inches per frame, everything looks normal. In the GIF animation, the green waves are like the fence panels. SteveBaker (talk) 02:55, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Thanx! (even though this wasn't my question :) DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 04:10, 21 January 2010 (UTC)

- This is more than just the "wagon-wheel effect" from old westerns. I saw an ultra-modern car TV ad the other day, and the same thing was going on. One would think with digitization they could make it "look right". But maybe people are so used to seeing it, that if it looked "right" they would think it looked phony? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 04:15, 21 January 2010 (UTC)

- Thanx! (even though this wasn't my question :) DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 04:10, 21 January 2010 (UTC)

- Nope - this is something completely different. If my three-spoked wheel example has the wheel rotating at 110 degrees per frame, the backwards 10 degrees per frame that you think you're seeing is a rock-solid effect, you can't keep looking at it and see it 'switch'. The GIF is changing direction because the animation is slowly increasing in speed until it hits the temporal aliasing speed - then, although the speed is still increasing, it appears to slow down, stop and then reverse. You can visualize that in the same way we did with the three-spoked wheel. Imagine a video shot out of the window of a car that's driving along parallel to a really long picket fence with vertical strips every 12 inches. If you drive at 12 inches per frame, the fence seems stationary - if you drive at 11 inches per frame, it seems to be moving backwards - at 6 inches per frame, you see twice the number of fence posts - but kinda flickery - at below 6 inches per frame, everything looks normal. In the GIF animation, the green waves are like the fence panels. SteveBaker (talk) 02:55, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- OK...I thought it was an issue of, "if you keep looking at this, it will switch," and that's why I compared it to the spinning/oscillating girl. With my understanding of it, and that's an apparently incorrect understanding as you explain it, my rationale, which is now false, was as follows: If it's only that after a few seconds of watching the little GIF file above that it appears to switch, why does it appear to go in the opposite direction even if one doesn't look at it for the first half of the video. DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 02:42, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

circuits

what will happen if we put a resistor of,say, R1 and a simple wire say copper wire in parallel in a circuit made up of copper wire,with a battery and a switch only. what will be the resistance in the circuit.could it be solved like that

1/0 + 1/R1 = 1/Rp (as the resistance of copper wire is 0)

where Rp is total resistance in parallel. —Preceding unsigned comment added by Myownid420 (talk • contribs) 02:51, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- The resistance of a copper wire is not zero, see here for some numbers. From my knowledge of electronics, what you seem to be suggesting would most likely result in a short-circuit. Such a circuit would have close to (but not exactly) zero so you can pretty much ignore the resistor since almost all the current is going to flow through the copper wire. Also, you probably shouldn't try to divide by zero. - Akamad (talk) 03:06, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- The current will be large and limited by the resistance in the battery. As Akamad said you can ignore the parallel resister. If there is no resistance in the wire or battery the current will still be limited by inductance, and will grow linearly with timeGraeme Bartlett (talk) 08:12, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

plate changing speeds

Is this possible the plate movement will start out slow then end up moving fast? Because Africa 100 million years ago move faster now it slow to 2 cm/year. Is this possible Antarctica could eventually move as fast as Australian plate? WHat changes the speed motion? Could Australia eventually slow down?--69.228.145.57 (talk) 04:49, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- It is possible, and the direction of movement could change over time. What happened in the past can be found by the geomagnetic reversal timing signatures on the ocean floor. Predicting the future is more difficult. One book I read stated that the circulation in the mantle is turbulent and so it varies over time and is not simply predictable. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 08:42, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

nuary 2010 (UTC)

Tree of Life in circular form

A question rather than an answer from me for a change. The current Evolution articles' template features a diagram of the "Tree of life" in a space-saving circular layout, and in recent years I've seen other similarly circular versions elsewhere. Does anyone know where this general circular layout of it originated? (The reason I ask is that, while desk-editing a school science textbook in 1990, I was asked by the authors to design and/or source a number of diagrams and other pictures, including a very simple Tree of life, and came up with just such a near-circular layout in order to save space on the page. Although I had no previous example consciously in mind it seems very unlikely that circular Trees of Life weren't already in use and quite probable that I'd seen one before.) 87.81.230.195 (talk) 04:59, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- It has developed gradually. At [1] you can see Darwin's own sketch where the branches from the roots go in different directions. This hand-made tree: [2] from Science in 1997 uses a similar space-saving layout. The circle appears naturally as you add more and more branches. The web-based generator for the image you refer to can be found at [3]. The company behind it claims it's a novel type of visualization, so according to them the style orignated in 2006. Though in my opinion, the main driver is large tree-of-life databases. EverGreg (talk) 09:45, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Some more examples: Carl Woese in 1988 (figure 4) [4] Cover of Molecular systematics 1996: [5]. There's also an example you may have come across in school. There's a circular diagram where each kid in class starts off in the centre and then moves outward in a circular tree according to genetic properties such as gender, ability to roll your tongue e.t.c. It's not a phylogenetic tree, but gives an image of genetic similarity. EverGreg (talk) 10:06, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks for those suggestions, EverGreg, but some of those examples are, like Darwin's familiar original (published, incidentally, by the same firm I was working for), radial rather than circular, while the circular ones postdate my own usage. I certainly never encountered your school exercise (which would have to date back nigh-on four decades for me to have done so). Surely someone can come up with a good pre-1990 example to save me from the hubris of suspecting I may have originated it myself? 87.81.230.195 (talk) 10:56, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

Electrical Heating Distribution

So the above thread about heat pumps has me wondering about electrical heating in general. In what parts of the world is electrical heating commonly used to heat buildings? Here in (Suburban) Minnesota gas heating is the norm, and electrical heating is pretty much unheard of, except for maybe a small space heater in an ice shack or something. I understand that in the UK it's pretty common to take advantage of lower energy prices at night with a storage heater. We also had someone from Australia and Texas say that they had electrical heating. It seems to be that electrical heating is more common more temperate places. Do southern Europeans use electrical heating on a large scale? What about northern Europeans? I assume that Russians use natural gas (because they have enough of it), but I don't really know. What about in developed Asian countries like Japan? Buddy431 (talk) 05:23, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Electric heating is cheap to install, so low cost systems in Australia use a simple fan over hot element heating. More sophisticated systems could be in slab or floor eating or the storage system using off peak electricity you mentioned. Reverse cycle systems can be quite efficient giving a gain of 4x the energy consumed. To use gas, reticulation infrastructure is needed in the form of plumbing or big gas bottles. Some do use this. Coal in furnaces is rare, and in the past there used to be oil heaters. Before this burning wood in fireplaces or stoves was common. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 08:09, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- I had electric baseboard heaters when I lived in Tennessee. And I wasn't the only one. I knew several people, especially those who were living in trailers who had electric heat. Dismas|(talk) 09:51, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- In some parts of canada hydroelectric electricity is cheaper than gas. (Probably due to subsidies.) So electric heat is used. Otherwise electric heat is used when the installation cost of a gas burner is more than the savings of using gas vs electricity. Electric heat is very cheap to install. U.S. view: This is typically in the south where it doesn't get that cold. You have sort of a continuum - in the north, all gas. No A/C, so it's usually radiators (water). In the middle it's electric heat, and no A/C at all. In the south you have A/C (meaning the ductwork is anyway already there), so they use a central heat source, and they do gas. This is generalizing a lot of course. Also some places do not have gas service, and oil in not available. So electric is the default. These days, even in the north new construction comes with A/C, and the price of electricity has gone up more than gas, so it's pretty much all gas if it's available. Ariel. (talk) 10:27, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Electrical heating is clearly the norm in Norway, a developed country in the north. Historically, we had very cheap hydroelectricity, you certainly don't need subsidies for this. Prices do rise as transmission capacity to the rest of Europe improves, though. There are (almost?) no distribution nets for gas in Norway, and I don't think it would be economic to build those; gas is piped from Norway's large sub-ocean gas fields via stations on the coast across the North Sea to Britain and the Netherlands. Large buildings do use oil for fuel though. Many single-unit houses have wood ovens as a supplement. I think electricity is the norm in Sweden and Finland as well. Jørgen (talk) 12:55, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Electricity prices for the Nordic countries are here, in EUR/MWh, it would be interesting if some US users could compare this to their local heating prices (assuming 100% electricity efficiency). The electricity market in Norway is very competitive, I think the end-user prices are very close to the "market trading" prices (though transmission cost of 0,39 NOK/kWh (ca 7 US cents) comes in additition (at least that's the price in my area)) Jørgen (talk) 13:11, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Here is a relatively informative article per your question, as you can see from the graph $.07 US/kwh is pretty darn low, a price almost no one in the US has seen since 2005. Depending on the natural gas spot market in the US, the price tends to be around 1/3 as much to get a BTU from NG compared to electricity (assuming the NG furnace is of modern efficiency). --Jmeden2000 (talk) 16:52, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Electricity prices for the Nordic countries are here, in EUR/MWh, it would be interesting if some US users could compare this to their local heating prices (assuming 100% electricity efficiency). The electricity market in Norway is very competitive, I think the end-user prices are very close to the "market trading" prices (though transmission cost of 0,39 NOK/kWh (ca 7 US cents) comes in additition (at least that's the price in my area)) Jørgen (talk) 13:11, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- In some parts of Russia and Ukraine, they still use coal gas... 24.23.197.43 (talk) 07:22, 23 January 2010 (UTC)

difference between sea and ocean

what is the technical differnce in the definition of a sea and an ocean?Denito (talk) 07:46, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Sea is small and Ocean is big. eg sea of Galilee is pretty miniature, but famous. The oceans currently on earth are pretty fixed in number, but perhaps your definition request is important to naming oceans in the geological past of earth, or on other planets. The Sea of Marmara is claimed to be the smallest sea, but sea of Galilee is smaller. According to Wikipedia a Sea is large, and an ocean is major. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 08:02, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Even worse though, while sea of Galilee is a traditional name, it is actually a freshwater lake. Googlemeister (talk) 14:41, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- To further confuse things, some seas are part of a larger ocean (for example, the Carribean Sea is part of the Atlantic Ocean; the Andaman Sea is part of the Indian Ocean), whereas other seas, such as the Baltic Sea are separate bodies of water that are connected to oceans. See marginal sea and mediterranean sea. Gandalf61 (talk) 10:31, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Oceans abut and separate continents. A sea is just some water on which one can sail a boat. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 13:15, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Hmmm. The Bering Sea separates North America and Asia; the Red Sea lies between Asia and Africa; and the Mediterranean Sea has coastlines in Europe, Africa and Asia. But they are not oceans. Gandalf61 (talk) 15:10, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Indeed. I did not claim that oceans have a monopoly on what they do. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 20:44, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Hmmm. The Bering Sea separates North America and Asia; the Red Sea lies between Asia and Africa; and the Mediterranean Sea has coastlines in Europe, Africa and Asia. But they are not oceans. Gandalf61 (talk) 15:10, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Oceans abut and separate continents. A sea is just some water on which one can sail a boat. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 13:15, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- To further confuse things, some seas are part of a larger ocean (for example, the Carribean Sea is part of the Atlantic Ocean; the Andaman Sea is part of the Indian Ocean), whereas other seas, such as the Baltic Sea are separate bodies of water that are connected to oceans. See marginal sea and mediterranean sea. Gandalf61 (talk) 10:31, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Because "ocean" is of European origin, it should be obvious that the use came from early Europeans. Add to the concept of an ocean the earlier fact that the world was flat, an ocean was the body of water that, if you sailed through it, led to the edge of the world. The world consisted of Europe, Asia, and Africa. The four oceans (just four at the time) were to the north, east, south, and west of the world. Once the world was proven round, there was no need to change the name. -- kainaw™ 15:24, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Not to get too humanities on you, but that brief history of European knowledge of geography is ridiculously inaccurate. The Earth was known to be round in ancient and medieval times: for example, see our article on mappa mundi. 86.178.230.208 (talk) 17:20, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- I think there is also considerable geographical variation in the use of the term. I've noticed that Americans use the word "Ocean" in many contexts where the British would say "Sea". That may be because the USA is bounded by a couple of oceans where the Brit's have the North Sea on one side and an Ocean on the other. But it's only a matter of linguistics - there isn't any science behind it, beyond some vague concept of size. However, people still talk about "Sailing the Seven Seas"...when they probably mean something like "Four oceans and three seas". SteveBaker (talk) 19:11, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- To be more "humanities" in my answer... The English term "Ocean" comes from the Greek Oceanus. It is a concept of a Greek god represented as a world ocean upon which the world floats. The "flat" world concept is a simplification of the of concept of a round world floating in Oceanus. Many cultures named the coastal waters, but continued to refer to the unknown waters as being part of Oceanus, or an Ocean. The modern view of the world ocean is slightly romanticized with the Greek concept of an ocean. Atlantic comes from Greek Atlas, an offspring of Oceanus. Arctic comes from Greek Arktikos - the great bear in the northern stars. Antarctic is away from the bear. Pacific was named a long time later with a Latin name. It seems to me that Magellan should have known enough to give it a Greek-based name. However, the concept of an unknown ocean is what is different about the oceans and the seas. In modern times, very little is unknown. We just continue to use the terms here and there out of tradition. -- kainaw™ 20:22, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- [citation needed] --Mr.98 (talk) 20:37, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Did you consider looking at Ocean, Oceanus, World ocean, or Atlas (mythology) before requesting a citation? -- kainaw™ 21:05, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Our article Oceanus attributes that view to some scholars. Do you have a good secondary source we could use to improve the article? Our article World ocean doesn't really talk about it, because it is discussing the actual, existent world ocean. Our article Ocean briefly mentions the idea under the heading culture, but has no sources. Our article Atlas of course mentions that he was considered Oceanus's son, but I don't think anyone was disputing that. It says nothing about this (presumably old even to the ancient Greeks) conception of the world. None of these articles mention four oceans to the north, south, east and west of the world. So maybe Mr.98 did read the articles. In any case, some citation would be welcome to improve these articles (as well as our collective answer). 86.178.230.208 (talk) 18:43, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- I just don't buy the explanation you're giving for how the distinctions came about in our modern world. The original poster is asking about how we might define things today, and appealing to Greek myths is probably incorrect. Geography went through quite a few changes since the Greeks. --Mr.98 (talk) 21:51, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Our article Oceanus attributes that view to some scholars. Do you have a good secondary source we could use to improve the article? Our article World ocean doesn't really talk about it, because it is discussing the actual, existent world ocean. Our article Ocean briefly mentions the idea under the heading culture, but has no sources. Our article Atlas of course mentions that he was considered Oceanus's son, but I don't think anyone was disputing that. It says nothing about this (presumably old even to the ancient Greeks) conception of the world. None of these articles mention four oceans to the north, south, east and west of the world. So maybe Mr.98 did read the articles. In any case, some citation would be welcome to improve these articles (as well as our collective answer). 86.178.230.208 (talk) 18:43, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Did you consider looking at Ocean, Oceanus, World ocean, or Atlas (mythology) before requesting a citation? -- kainaw™ 21:05, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- [citation needed] --Mr.98 (talk) 20:37, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- To be more "humanities" in my answer... The English term "Ocean" comes from the Greek Oceanus. It is a concept of a Greek god represented as a world ocean upon which the world floats. The "flat" world concept is a simplification of the of concept of a round world floating in Oceanus. Many cultures named the coastal waters, but continued to refer to the unknown waters as being part of Oceanus, or an Ocean. The modern view of the world ocean is slightly romanticized with the Greek concept of an ocean. Atlantic comes from Greek Atlas, an offspring of Oceanus. Arctic comes from Greek Arktikos - the great bear in the northern stars. Antarctic is away from the bear. Pacific was named a long time later with a Latin name. It seems to me that Magellan should have known enough to give it a Greek-based name. However, the concept of an unknown ocean is what is different about the oceans and the seas. In modern times, very little is unknown. We just continue to use the terms here and there out of tradition. -- kainaw™ 20:22, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- I think our definition on the ocean page is pretty good. "An ocean is a major body of saline water, and a principal component of the hydrosphere." Now, obviously the line between what isn't a principle component of the hydrosphere or not is somewhat arbitrary, but the acknowledged oceans dwarf any candidate large seas considerably. The smallest ocean is some five times larger than the largest sea, while the rest of the oceans are some 20X larger. IMO the only questionable inclusion is whether the Arctic Ocean counts as an "ocean" or not. The Arabian and South China seas are both very small by comparison to the other oceans. --Mr.98 (talk) 20:37, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Well...kinda...but the division of a more or less contiguous irregular shape into regions is entirely arbitary anyway. Where exactly the South China sea ends and the Pacific starts is a totally arbitary line. SteveBaker (talk) 02:40, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Agreed for the most part. (In some cases, underlying geology does make certain waters have a different character than others, I believe, which would seem like a good reason to delineate them, if you were a sailor.) --Mr.98 (talk) 21:51, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Well...kinda...but the division of a more or less contiguous irregular shape into regions is entirely arbitary anyway. Where exactly the South China sea ends and the Pacific starts is a totally arbitary line. SteveBaker (talk) 02:40, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

Oceans occur in the unlikeliest places. Thomas Babington Macaulay talked of The old philosopher is still among us ...blinking, puffing, rolling his head, drumming with his fingers, tearing his meat like a tiger, and swallowing his tea in oceans. -- Jack of Oz ... speak! ... 00:29, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

Is one difference that all the oceans on our planet connect together wrapping around the planet while the seas are mostly disconnected from being a solid unit, themselves separated from each other either by oceans or by land? --Neptunerover (talk) 09:08, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Hmmmm. Black Sea, Aegean Sea, Mediterranean Sea, Ionian Sea and Adriatic Sea. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 13:56, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- No. It really doesn't take much effort to find counter-examples for those kinds of propositions (it would be nice if you did that rather than just posting wild speculation). For example:

- The Mediterranean Sea does not connect to any oceans directly because the Alborean Sea is in the way.

- The Alborean Sea does connect to the Atlantic ocean but only via the straights of Gibralta (is that a 'connection' or not?).

- The Aral Sea is completely land-locked and doesn't connect to any other bodies of water whatever.

- The Sargasso Sea is completely surrounded by the Atlantic ocean and touches no land or other regions of water. It's boundaries are defined by ocean currents and as such, it doesn't even stay in the same place from one year to the next!

- The Argentine Sea is nothing much more than an arbitary strip of water that is some unspecified number of miles wide adjoining a vaguely delimited stretch of coastline on the edge of the Atlantic ocean.

- There is no solid rule here - it's a mess. Which is fine if you are just giving random bits of water pretty names - but has zero scientific meaning.

- SteveBaker (talk) 14:06, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

Tsk, tsk. "The ALBORAN Sea does connect to the Atlantic ocean but only via the STRAITS OF GIBRALTER." Cuddlyable3 (talk) 17:02, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Where is the "Alboran Sea", anyway? On my map, there's not such a thing, and the Straits of Gibraltar connect the Mediterranean directly to the Atlantic Ocean. Has that region's geography undergone some major tectonic changes? 24.23.197.43 (talk) 07:19, 23 January 2010 (UTC)

- With the exception of oddities like the Sea of Galilee, seas and oceans are all saltwater, right? Misnamed things stay that way. Like Cape Cod, which is not a cape, it's a peninsula. Or, thanks to the canal, it's an island. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 17:19, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- When you come right down to it - geographers have a hard time of keeping names and definitions in order. (I write this from somewhere in the middle of the island of northandsouthamerica - a piece of land surrounded entirely by water). SteveBaker (talk) 00:09, 21 January 2010 (UTC)

- And as with Cape Cod, the canal probably creates two islands out of one. Meanwhile, ponder this, and not just the bizarre fact that most of us live "in continents": Sometimes within a continent you'll find a lake that's self-contained. For example, Crater Lake in Oregon. That body of water has an island within it, an extinct volcanic cone. That island has various little pools of water. So that island also has small "lakes" within it. And some of those little pools have little bitty islands within them... and so on. Hey, why do I suddenly feel like this should be on the math page? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 04:38, 21 January 2010 (UTC)

- When you come right down to it - geographers have a hard time of keeping names and definitions in order. (I write this from somewhere in the middle of the island of northandsouthamerica - a piece of land surrounded entirely by water). SteveBaker (talk) 00:09, 21 January 2010 (UTC)

- Does depth have anything to do with it? Are there any seas as deep as the shallowest ocean's maximum depth? --Neptunerover (talk) 15:50, 21 January 2010 (UTC)

how do i get annoying stuff like picture of the day , poker ect to stop appearing on my updates? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Killspammers (talk • contribs) 14:24, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Do you mean on your newsfeed (items that your friends have posted), on your wall (items that applications have posted whilst you're using them) or on your notifications? If you are asking how to hide certain application updates from friends appearing on your newsfeed, you can hover over the item and a 'Hide' button will appear. On clicking this you will get the option to either hide all posts from this user or all posts from this application. You can also do this by clicking 'Edit options' on the footer bar at the bottom of your feed. To stop applications that you use posting to your wall automatically you have to alter the settings for each of these individually. Open an application and hover over 'Settings' on the header bar at the top of the screen, each application has it's own settings page which you would then be able to see and open. Click on this and go to 'Additional permissions' and untick 'Publish recent activity to my Wall'. If you are asking how to stop certain applications appear in your notifications - click on the notification icon in the bottom right of the screen, click 'See more' to go to the notification settings page and untick those applications you don't want to recieve information from on the right hand side. HTH. Nanonic (talk) 15:17, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

no i want to delete the application from my facebook. how do i do it —Preceding unsigned comment added by Killspammers (talk • contribs) 15:57, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Well, you can start by having a look at facebook's own help on this]. Nanonic (talk) 16:33, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

cyclisation of tryptophan

From the indole article: "Since the pyrrollic ring is the most reactive portion of indole, nucleophilic substitution of the carbocyclic (benzene) ring can take place only after N-1, C-2, and C-3 are substituted."

Is this really true if intramolecular substitution is taking place? Say the C2 site is protected, and C3 site is already occupied. I think if the amino group is protected (maybe by simple acid) the carboxy group will attach on the benzene ring. Can someone confirm this? If so, I'm going to change the article. John Riemann Soong (talk) 15:07, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Intramolecular effects can beat intrinsic reactivity, but that doesn't change the fact of the intrinsic reactivity. The result for any specific reaction is always a balance (and rationalization based on) of all competing effects. DMacks (talk) 18:50, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, but that is a preference for substitution, right? I don't think the article should be speaking in absolute terms. John Riemann Soong (talk) 20:22, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

Woman sentenced to 4 years for torching boyfriend's penis

how is it possible she got only 4 years? why didnt they give her 20 to 40 years or even life ? if a man raped her hed get like 10 years but she does something a million times worse and gets only 4 years? http://www.cbc.ca/canada/montreal/story/2007/02/28/qc-andreerene.html

- Your opinion is that it was "a million times worse" than rape. Others may disagree with you. In any case, to go with your analogy, I'm not sure what the standard sentence for rape is in Canada, but I'd doubt it's anything like "20 to 40 years or even life". Does anyone know? --Dweller (talk) 16:08, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- According to this website, the maximum possible sentences for sexual assault crimes range depending on the exact conviction, from 6 months to life. The judge gets a lot of discretion as to what exact sentence is issued though. It article implies that the sentencing had a lot to do with mitigating circumstances—the defendant's history of abuse, psychological problems, etc.—which are often taken into account for such things. Whether it is a truly just sentence or not, I don't know, and I'm sure informed people would differ. --Mr.98 (talk) 17:56, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Personal opinions but I don't give a shit; "mitigating circumstances" of the rapist should have zero influence on their sentence. I don't give a shit if the rapist is temporally mentally insane or whatever the fuck other excuses they boil up - rape is rape and imo rapists should be locked up for life.

- According to this website, the maximum possible sentences for sexual assault crimes range depending on the exact conviction, from 6 months to life. The judge gets a lot of discretion as to what exact sentence is issued though. It article implies that the sentencing had a lot to do with mitigating circumstances—the defendant's history of abuse, psychological problems, etc.—which are often taken into account for such things. Whether it is a truly just sentence or not, I don't know, and I'm sure informed people would differ. --Mr.98 (talk) 17:56, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- The Wikipedia Science Reference Desk isn't a discussion forum for opinions, debates, and chats about current events. Perhaps you could find a suitable internet forum for this type of question? TenOfAllTrades(talk) 16:10, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

(Also where's the science in this question? I suppose there's Fire involved but still... 194.221.133.226 (talk) 16:17, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- I did not find any information out there, other than your link, about this 2007 sentencing, but I would guess that, under the Canadian Criminal Code, section 268, she was probably charged with "aggravated assault", for endangering the life of the complainant, which means she can be imprisoned for up to 14 years. By contrast the penalties for rape in Canada (page 4 of the PDF) are maximums of 10 years ("sexual assault"), 14 years ("sexual assault with a weapon, threats to a third party, or causing bodily harm"), or life ("aggravated sexual assault") — the latter meaning that the rapist also "wounds, maims, disfigures, or endangers the life of the complainant". Those are the maximums — I didn't find any information about why in this specific case she got a lesser prison term (assuming I was even right about the charge brought). I learned two things looking this up — the word "rape" is no longer in the Canadian criminal code; and the first rape law in the USA reduced the penalty significantly if the female victim were single (!). Comet Tuttle (talk) 17:56, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

so why wasent she givin the maximum sentence 14 years? also if you would rather get your genitals set on fire than get raped u need your head examined. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 67.246.254.35 (talk) 18:44, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Because a judge, probably in light of the aforementioned mitigating circumstances, decided to sentence her otherwise. --Mr.98 (talk) 19:01, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- The general idea is that you want to punish unjustified, capricious malice. It was the opinion of the sentencing parties that Ms. Flame didn't have that much malice. Probably they thought she was somewhat justified. She evidently thought she was justified at the time of doing it, and that would be good enough for me if I were a juror. Vranak (talk) 20:30, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- At least in Germany, and I guess in many other countries, first offenders usually get sentences much below maximum. One reason is that the public prosecutors and judges are civil servants with a life career, i.e. they are professionals and do not have to play to public sentiment. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 22:15, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- I have tried to find the case on the court's website, but it doesn't seem to be there. (If anyone else wants to try, this seems to be the right site, but searching for René under Court of Quebec Criminal division doesn't find anything - the website is in French, however, which is a language I don't actually speak, so a French speaker may have better luck.) --Tango (talk) 01:50, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

Nothing is worse than rape. /thread —Preceding unsigned comment added by 82.43.91.83 (talk) 22:05, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Murder? Mass murder? Torture? Child abuse? Genocide? You are entitled to your opinion, but it is far from a universally held one. --Tango (talk) 01:37, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- I would rather all those things happen than rape, I would kill myself before rape. Yes, it's not a universally held opinion as you pointed out.

- Again, this is not a debate forum. Please stop it. --Anonymous, 01:50 UTC, January 20/10.

- I initially read the question as "touching" and the punishment seemed, well, excessive. Edison (talk) 18:02, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- I wonder what the punishment would have been if she coldcocked him? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 18:38, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

Autocrine signalling

From what I understand, autocrine signalling is where a cell releases a transmitter to purely act on its own receptors, so that it can talk to itself. Is there any good reason for this, or is my premise wrong (i.e. a cell never wants to talk just to itself)? At first glance it appears to be inefficient, probably analogous to sending yourself a text message when you could just store it in the draft folder and avoid the SMS cost. Or writing down "pour yourself a glass of water" and reading it, instead of just pouring yourself a glass of water. --Mark PEA (talk) 17:30, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- I suppose you've never written a todo list? My first thought about its utility is that it lets the cell react over an extended period of time (the lifetime of the transmitter) to even a transitory stimulus. --Tardis (talk) 18:39, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Well the reason humans write todo lists is because their memories can fail them, otherwise they would just "remember" their todo list (it's the same reason why I think in my head, as opposed to speaking all my thoughts, because that would be a waste of energy*). Also I'm not denying that it has utility, it just seems there would be a more effective way of doing this rather than synthesizing large numbers of receptors and transmitters, releasing them to the outside, and then detecting their signal again. Of course this is useful in paracrine signalling or synaptic signalling, where autoreceptors can be used to maintain negative feedback systems. But for 100% autocrine signalling it is a waste of energy.

- *Of course there are reasons to talk to oneself, not for self-communication but to assess one's voicebox, or just being an irrational, drunk idiot :) --Mark PEA (talk) 21:10, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- There are many biological processes in which amplification of a signal must occur: autocrine signalling is one mechanism for this. Of course it is "inefficient" from an engineering standpoint--- one more example of the difference betweened designed and evolved complex entities. alteripse (talk) 19:14, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- (ec) I might speculate that this is an example of evolution deciding to 'reuse its code', as a programmer might say. Rather than having to evolve a whole new set of signalling proteins to trigger some sort of signalling cascade in the middle of an existing pathway, autocrine signalling means that a cell can just use already-existing genes and proteins to trigger a signal in the 'usual' way from an 'external' stimulus. While it might not appear to be the most efficient method, it works. (Consider this — let's say that you are standing in front of a photocopier, and you just happen to need a sheet of blank paper. One solution is to try to figure out how to unlatch and open the paper trays, locate the pages of the correct size, remove a single sheet, make sure everything is closed back up properly, and declare success. Another solution is to just push the copy button on the front panel without putting an original on the glass. Presto — out comes the sheet you wanted, no diassembly or fiddling required. Evolution has a habit of reusing old methods with minor tweaks; it's 'easier' than generating whole new pathways from scratch.)

- I'll also note that the definition of autocrine signalling is often a bit broader than simply a single cell acting on itself. It can also include cases where a particular cell signals not just to itself, but also to other cells of the same type. The applications of that sort of signalling are more obvious. Among other things, it allows groups of cells to 'assess' their surroundings by 'polling' their neighbors. A cell can 'sense' whether (for example) a lot of its neighbors are stressed out and respond accordingly. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 19:23, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, I can understand it in this sense, although my understanding is that this is a form of paracrine signalling. All the answers still seem to be evidence of Unintelligent Design, as I think with the massive amount of junk DNA, the cell could easily have some genes which allow it to talk to itself intra-cellularly that use less energy than this current way. Of course all of this relies on the premise that autocrine signalling is used purely for self-talking, which it probably doesn't (thus, I'd rather it were called pseudoautocrine signalling, since some paracrine signalling is thrown in). --Mark PEA (talk) 21:10, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- In general, autocrine signalling refers to messages between cells of the same type (including messages sent and received by the same cell), whereas paracrine signalling involves signalling between cells of different types or lineages. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 21:57, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks, my original premise was wrong then. (Retrospectively I now notice that the autocrine article actually states that this type of signalling is amongst the same type of cells). --Mark PEA (talk) 23:48, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- While autocrine signaling may involve more than one cell, there is a decent argument for a cell signaling itself in this way. For example, T cells use IL-2 in an autocrine loop, upregulating their high-affinity IL-2 receptor when stimulated. The extracellular loop provides a mechanism for nearby cells to sense and modulate the T cell's activation. Similar thing can happen with type I interferon signaling - if RIG-I is activated by dsRNA, interferon beta is one product, which may act in both autocrine and paracrine fashion to promote antiviral responses in both the original cell and its neighbors. I don't think your original premise was wrong at all, if I understood it correctly. -- Scray (talk) 01:48, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- In your scenario... (1) stimulus tells cell to to signal to itself → (2) cell produces & releases transmitters → (3) transmitters bind to membrane receptors → (4) receptors activate signalling pathways, which tell the cell to synthesize more receptors (upregulation).

- My original question was asking why not just have a scenario where... (1) stimulus tells cell to "signal to itself" → (2) cell activates signalling pathways directly (that receptors in the step 4 above activate), which tell cell to synthesize more receptors. Of course, the answer seems to be that the autocrine signalling also signals to other cells (which opposes my original premise), or that evolution just hasn't had the selection pressure to create new code to do it a slightly more efficient way. --Mark PEA (talk) 10:32, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Not only that, Mark, but in a case in which a type of cells is already set-up to receive an external message via SIGNAL A, it would be pretty efficient for that cell type to simply release signal A to set off the desired chain of events, rather than develop an entirely new intracellular pathway (and this rationale would suffice even if your autocrine example is a single cell, such as a lonesome leukocyte, etc. DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 04:20, 21 January 2010 (UTC)

- While autocrine signaling may involve more than one cell, there is a decent argument for a cell signaling itself in this way. For example, T cells use IL-2 in an autocrine loop, upregulating their high-affinity IL-2 receptor when stimulated. The extracellular loop provides a mechanism for nearby cells to sense and modulate the T cell's activation. Similar thing can happen with type I interferon signaling - if RIG-I is activated by dsRNA, interferon beta is one product, which may act in both autocrine and paracrine fashion to promote antiviral responses in both the original cell and its neighbors. I don't think your original premise was wrong at all, if I understood it correctly. -- Scray (talk) 01:48, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks, my original premise was wrong then. (Retrospectively I now notice that the autocrine article actually states that this type of signalling is amongst the same type of cells). --Mark PEA (talk) 23:48, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- In general, autocrine signalling refers to messages between cells of the same type (including messages sent and received by the same cell), whereas paracrine signalling involves signalling between cells of different types or lineages. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 21:57, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, I can understand it in this sense, although my understanding is that this is a form of paracrine signalling. All the answers still seem to be evidence of Unintelligent Design, as I think with the massive amount of junk DNA, the cell could easily have some genes which allow it to talk to itself intra-cellularly that use less energy than this current way. Of course all of this relies on the premise that autocrine signalling is used purely for self-talking, which it probably doesn't (thus, I'd rather it were called pseudoautocrine signalling, since some paracrine signalling is thrown in). --Mark PEA (talk) 21:10, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

Technical vs managerial career track

I'm hoping you RefDesk folks can refer me to some essay, website, book, etc that discusses the choice faced by a scientist or other technical worker when presented with the opportunity to move into management. (I'd love to discuss this with someone, but I understand the RefDesk isn't the place for it). ike9898 (talk) 17:41, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- See Dilbert (sorry). Looie496 (talk) 18:00, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- I'm not familiar with any books confronting this career choice, but googling manager career site:slashdot.org will yield many threads on the subject. Warning: Many "contributors" are grousing computer programmers who believe all management is counterproductive micromanagement. If you're looking for books on technical management (rather than focusing on the career choice which was your actual question), The Mythical Man-Month is considered a classic of software development management. Comet Tuttle (talk) 18:33, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Managers get paid more and they are the boss. 78.151.106.238 (talk) 19:08, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- In my particular situation (US government), the difference in pay is small and and in my current situation as a researcher, I have a fair degree of autonomy. Both these factors reduce the advantages of moving into management. ike9898 (talk) 19:21, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- That may be true now, but think what will happen in the future. My guess is that in the long run you will be earning more money and having more status. 78.151.106.238 (talk) 20:38, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- In my particular situation (US government), the difference in pay is small and and in my current situation as a researcher, I have a fair degree of autonomy. Both these factors reduce the advantages of moving into management. ike9898 (talk) 19:21, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- If you like long meetings, presenting in front of groups, and having to nag deadbeats who are late to work and who slack off, then, by all means choose management. If you don't like those things and like to create things of value yourself, then choose the technical path. Technicians can pat themselves on the back and say, "I built that web site" or "I made that program." Managers aren't bad people. Some take joy in befriending their employees and rewarding them when they succeed. But eventually, you have to discipline them, too. That's not always a fun thing to do.--Drknkn (talk) 19:33, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Its just as easy to spin that the other way - technicians would tend to do more repetative work with less responsibility, hence more boredom and lack of fulfillment. There are many different styles and fads of management or (not the same thing) leadership - autocratic, consultative, etc etc. Take your pick. And you can build something without doing the labouring yourself - hence you build bigger and more impresive things. 78.151.106.238 (talk) 20:38, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Engineers are people who can do what they don't control. Managers are people who control what they can't do. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 20:39, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Its difficult to recommend a book without having more information on what kind of management you see yourself doing, and what aspect of management interests you. Could you supply more details please? 78.151.106.238 (talk) 20:49, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- More details as requested:

- The most sensible and accessible type of management for me is management in government research agency. Such managers are involved in research in a sense, but they interact with the research indirectly, never hands-on.

- I'm not interested in management in particular, but I have the type of personality that I can get interested in also anything (e.g. editing the Wikipedia article on Ladies' Home Journal - I am a hetero male and do not read this magazine!)

- It seems to me that windows of opportunity to switch tracks are limited. I'm concerned that I might regret letting such a window pass me by.

- It seems that many older people, even older technical people, have less patience, interest and competence with new technology. Presumably, someday I'll be one of those people.

- ike9898 (talk) 21:11, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Thank you for assuaging natural worries about how reading too much might be influencing you, though that was TMI. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 12:03, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- What?? ike9898 (talk) 14:35, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- The small print comment is about your macho declaration about not reading a ladies' magazine. Some people would be shy about such things. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 16:49, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Oh, OK. I offered the information to make it clear that I can get interested in things I have no good reason to be interested in. ike9898 (talk) 17:17, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- The small print comment is about your macho declaration about not reading a ladies' magazine. Some people would be shy about such things. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 16:49, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- So now the question is, what sort of management do managers do in a government research agency? 78.149.139.201 (talk) 23:37, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- What?? ike9898 (talk) 14:35, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- More details as requested:

- It is difficult to give the reply requested as a) from what the OP has said the OP may have been offered a supervisory job or perhaps a project management role rather than an executive management role, b) there's plenty of management theory but nearly all the time managers never refer to it according to personal experience and Mintzberg, c) the stuff you read in textbooks will probably have little relation to what you actually do, d) there is an enormous amount of worthless garbage written about management or business, particulary popular American books I have to say. But, bearing that in mind you could have a look at Fayolism. Something to remember about Fayol is that the english version does not give enough or any emphasis to feedback and checking, both vital - interested to see that the article says this was due to a mistranslation of "checking" as "control" in English. The autocratic leadership style of that time is rightly far out of date. Do not mistake leadership for management - a common mistake. I've seen bad ignorant managers believe that (coercive) leadership is all that needs to done while the organisation falls to pieces because no management is being done. I remember reading this: Writers on Organizations by D.S. Pugh and David J. Hickson. I found this a few minutes ago www provenmodels dot com which gives details of many familiar thories, although it still makes the same mistake about Fayol. Wikipedia says its on its blacklist, do not know why, perhaps it is a Wikipedia rip-off, but at least it packages it in a nice way. This is mentioned in a couple of articles http://www.amazon.co.uk/Organization-Theory-Design-Understanding-Organizations/dp/0324422717/ref=sr_1_4?ie=UTF8 never read it myself. The reviewer Stan Felstead has reviewed a lot of management books http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/cdp/member-reviews/A39KA7J326RUCV/ref=cm_cr_dp_auth_rev?ie=UTF8&sort_by=MostRecentReview Update: If you like history I've found Management Thought by Jayanta K Nanda, which can be read in full online in Google Books. I'd like to read it myself. 92.29.57.199 (talk) 16:05, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- I see that Henry Mintzberg, perhaps the greatest living star of management theory, has recently had a book titled Managing published, in 2009. So although I've never read it myself, it would probably be worth reading. The first part of it that I read on Amazon mentions "evidence-based" books - unfortunately the majority of management books published are dross that is not evidence based. Rarely if ever do you find books that offer insights based on someone's personal experience without reference to academic publications - they are always garbage written in the first-person like a memoir and full of waffle. One thing that they never taught me in all my business training was how to handle the paperwork, and how important the mundane task of having a good up to date filing system is, so that the facts you need are readily at hand and quickly retrievable. 78.147.245.100 (talk) 11:59, 22 January 2010 (UTC)

Gaussian and SI Units of Charge

Hello everyone. Looking over pages for various units, I'm a little confused on how the relationship between coulombs and statcoulombs. Basically, if Coulomb's Law is defined differently in SI and gaussian units, the units on force must still be the same (mass length/time2). Setting the two forms equal to each other, I get a formula somewhat different to the one at the bottom of the statcoulomb page. I obtain

substituting in and throwing in a factor of for converting kilograms to grams and meters to centimeters, I get 1 statcoulomb = 2997924580 coulombs, ie the exact opposite of what the page says (and opposite everything that every other conversion table I've looked at said). What's wrong with my derivation? Thanks :) Bennybp (talk) 18:10, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- If you have two numerical values a and b for the charge, in SI coulomb and statcoulomb respectively, and numerical values f and g in SI and Gaussian force units, and numerical values r and q in SI and Gaussian distance units, then the equation for two charges of the same size is

- Obviously, g = 105f and q = 102 r, so

- If b=1, then

- It seems like you forget that if you have a larger unit of charge, the numerical value for a given real charge is smaller ;-)

- Icek (talk) 06:51, 22 January 2010 (UTC)

- That makes sense. Looks like I need to crack open my high-school math book again. Thanks a bunch! --Bennybp (talk) 06:23, 24 January 2010 (UTC)

Relation between angular velocity and torque

What is torque formula of roatating equipment, if equipment rotate at constant angular velocity? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Mananmodi11 (talk • contribs) 18:24, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- If the angular velocity is constant, the net torque is zero (just as if the net linear velocity is constant, the net force is zero). In real life, if there is a decelerating torque due to friction, that means you'll need to apply an equal and opposite torque to maintain the angular velocity. -- Coneslayer (talk) 18:30, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- That is true for an isolated body. A rotating part of equipment that transmit power, such as a gearwheel in a clock or a car transmission, can have constant angular velocity while exerting a high torque. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 20:34, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- What? It's the net torque on the "part of equipment" that then needs to be 0, not the torque it exerts on other things. Of course, there's an equal and opposite torque applied to it by the driven object, but there's also a torque applied to it by the "upstream" source (eventually by an off-center spring or gasoline explosion or…), and at constant angular velocity they add to 0. --Tardis (talk) 20:46, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Indeed. The car's transmission exerts a torque on the car's wheels and has a torque exerted on it by the car's engine. If the transmission has constant angular velocity, then those torques must cancel out. --Tango (talk) 01:06, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- So if we couple a Bugatti Veyron engine to SteveBaker's Mini and break its gearbox (sorry SteveBaker), was the net torque on the gears zero? Cuddlyable3 (talk) 11:52, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Probably not. I've never tried connecting a gearbox to an engine too powerful for it, but I expect the gears would spin faster and faster until they broke. If their angular speed is increasing, there must be a non-zero net torque. --Tango (talk) 12:54, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- The over-powered mini was being driven at constant speed up a steep hill when the errr...dysfunction manifested. That's my story anyway. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 16:42, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Probably not. I've never tried connecting a gearbox to an engine too powerful for it, but I expect the gears would spin faster and faster until they broke. If their angular speed is increasing, there must be a non-zero net torque. --Tango (talk) 12:54, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- So if we couple a Bugatti Veyron engine to SteveBaker's Mini and break its gearbox (sorry SteveBaker), was the net torque on the gears zero? Cuddlyable3 (talk) 11:52, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Indeed. The car's transmission exerts a torque on the car's wheels and has a torque exerted on it by the car's engine. If the transmission has constant angular velocity, then those torques must cancel out. --Tango (talk) 01:06, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- What? It's the net torque on the "part of equipment" that then needs to be 0, not the torque it exerts on other things. Of course, there's an equal and opposite torque applied to it by the driven object, but there's also a torque applied to it by the "upstream" source (eventually by an off-center spring or gasoline explosion or…), and at constant angular velocity they add to 0. --Tardis (talk) 20:46, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- That is true for an isolated body. A rotating part of equipment that transmit power, such as a gearwheel in a clock or a car transmission, can have constant angular velocity while exerting a high torque. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 20:34, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- The easiest thing is to think of Torque as being the rotational equivalent of Force in the linear realm. When you apply a net force to an object you get an acceleration - but in the real world, friction and drag provide opposing forces that increase with speed. At high enough speed, the friction and drag equal the propulsive force and the speed levels off. Same deal with torque - when you apply an unopposed torque, the object spins faster and faster - but eventually, friction and drag provide opposing torques that increase until you get a constant rotational velocity. SteveBaker (talk) 02:31, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- :rolleyes:

- where rotational speed is in revolutions per unit time. See torque. --Heron (talk) 19:29, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- I know that the OP said "constant angular velocity", but, to expand on SteveBaker's comment and answer the question implied in the heading, when the torque is unapposed it is equal to rate of change of angular momentum i.e. torque = moment of inertia times rate of change of rotational speed. (assuming a fixed axis of rotation) Dbfirs 17:57, 22 January 2010 (UTC)

The path of the moon through the sky

Would the path of the moon through the sky, from moon-rise to moon-set, always be part of a circle if viewed through a very large sheet of glass that was set vertical and parallel to the imaginary line from moonrise azimuth to moonset azimuth? I mean, an arc of a circle and not some other curve. 78.151.106.238 (talk) 20:32, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- Almost entirely, yes. It is based on the rotation of the Earth and the current tilt of your view in relation to the moon. It is slightly (very slightly) skewed because the moon is also orbiting the Earth. It isn't enough that you'd really notice over a single night. -- kainaw™ 21:37, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- No, it would be part of an ellipse, I think. It is a circle on the sky, but when you project it onto a plane (the glass) you'll get an ellipse unless your eye, the glass and the moon are lined up just right. You've mentioned where the glass is with respect the moon, but not where your eye is. --Tango (talk) 01:14, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- No -- and it's not even "a circle on the sky." While above (or below) the horizon, the moon moves forward in celestial longitude and right ascension. Between rising and setting, the movement is enough to make its path vary significantly from a segment of a circle. Only an outer planet at stationary retrograde/direct (or a star) would closelt approximate a segment of a circle; and while the inner planets at stationary would move enough to distort a circle, the distortion would be small enough that "circle" would be a reasonable term. But the moon moves too fast, and is never stationary. (The exception would be when it is above or below the horizon very briefly, as it would be during certain times of the month in high terrestrial latitudes.)

unlikeliest thing to happen that did in fact happen? (that we know of)

Hi,

"Of all the things that were unlikely to happen, but did anyway, which one had been the unlikeliest?" (that we know of)

is my question even meaningful, or does it misconstrue statistics? (this is not homework). Thanks. 84.153.196.174 (talk) 20:55, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- That your particular sperm fertilized the egg, against compitition from millions or perhaps billions of other sperm. That is probably the most unlikely thing in anyones life. 78.151.106.238 (talk) 20:58, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- No, it's the most certain thing in anyone's life. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 11:43, 20 January 2010 (UTC)

- Anything after the event has taken place is the most certain thing, no matter how extremely unlikely it was before the event. 92.24.85.238 (talk) 11:41, 21 January 2010 (UTC)

- Don't all sperm have the exact same DNA? What makes this not a distinction without a difference? 84.153.196.174 (talk) 21:00, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- No. They each have a different (overlapping) half of the source's DNA. --Tardis (talk) 21:04, 19 January 2010 (UTC)

- No, it's the most certain thing in anyone's life. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 11:43, 20 January 2010 (UTC)