Faust: Difference between revisions

Neil Clancy (talk | contribs) This is listed on the disambig page and merits no special preference |

|||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

==Sources of the legend== |

==Sources of the legend== |

||

The first printed source on the legend of Faust is a little [[chapbook]] bearing the title [[Faust chapbooks|''Historia von D. Johann Fausten'']], published in 1587. The book was re-edited and borrowed from throughout the 16th century. Other "Faustbooks" of that era include: |

The first printed source on the legend of Faust is a little [[chapbook]] bearing the title [[Faust chapbooks|''Historia von D. Johann Fausten'']], published in 1587. The book was re-edited and borrowed from throughout the 16th century. Other "Faustbooks" of that era include: |

||

no |

|||

* ''Das Wagnerbuch'' (1593) |

* ''Das Wagnerbuch'' (1593) |

||

* ''Das Widmann'sche Faustbuch'' (1599) |

* ''Das Widmann'sche Faustbuch'' (1599) |

||

Revision as of 18:05, 22 June 2010

Faust or Faustus (Latin for "auspicious" or "lucky") is the protagonist of a classic German legend. Though a highly successful scholar, he is unsatisfied, and makes a deal with the Devil, exchanging his soul for unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures. Faust's tale is the basis for many literary, artistic, cinematic, and musical works. The meaning of the word and name has been reinterpreted through the ages. Faust, and the adjective Faustian, are often used to describe an arrangement in which an ambitious person surrenders moral integrity in order to achieve power and success: the proverbial "deal with the devil". The terms can also refer to an unquenchable thirst for knowledge.[1]

The Faust of early books—as well as the ballads, dramas and puppet-plays which grew out of them—is irrevocably damned because he prefers human to divine knowledge; "he laid the Holy Scriptures behind the door and under the bench, refused to be called doctor of Theology, but preferred to be styled doctor of Medicine."[2]

Plays and comic puppet theatre loosely based on this legend were popular throughout Germany in the 16th century, often reducing Faust to a figure of vulgar fun. The story was popularized in England by Christopher Marlowe, who gave it a classic treatment in his play, The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus. In Goethe's reworking of the story 200 years later, Faust becomes a dissatisfied intellectual who yearns for "more than earthly meat and drink".[citation needed]

Summary of the story

Despite his scholarly eminence, Faust is bored and disappointed. He decides to call on the Devil for further knowledge and magic powers with which to indulge all the pleasures of the world. In response, the Devil's representative Mephistopheles appears. He makes a bargain with Faust: Mephistopheles will serve Faust with his magic powers for a term of years, but at the end of the term, the Devil will claim Faust's soul and Faust will be eternally damned.

During the term, Faust makes use of Mephistopheles in various ways. In many versions of the story, Mephistopheles helps him to seduce a beautiful and innocent girl, usually named Gretchen, who is destroyed. However, Gretchen's naive innocence saves her in the end and she enters Heaven.

However, Faust is irrevocably corrupted, and when the term ends, the Devil carries him off to Hell.

Sources of the legend

The first printed source on the legend of Faust is a little chapbook bearing the title Historia von D. Johann Fausten, published in 1587. The book was re-edited and borrowed from throughout the 16th century. Other "Faustbooks" of that era include: no

- Das Wagnerbuch (1593)

- Das Widmann'sche Faustbuch (1599)

- Dr. Fausts großer und gewaltiger Höllenzwang (Frankfurt 1609)

- Dr. Johannes Faust, Magia naturalis et innaturalis (Passau 1612)

- Das Pfitzer'sche Faustbuch (1674)

- Dr. Fausts großer und gewaltiger Meergeist (Amsterdam 1692)

- Das Wagnerbuch (1714)

- Faustbuch des Christlich Meynenden (1725)

The 1725 Faustbook was widely circulated, and also read by the young Goethe.

The origin of Faust's name and persona remains unclear; though it is widely assumed to be based on the figure of Dr. Johann Georg Faust (c. 1480–1540), a magician and alchemist probably from Knittlingen, Württemberg, who obtained a degree in divinity from Heidelberg University in 1509, scholars such as Frank Baron[3] and Dr. Leo Ruickbie[4] contest many of these previous assumptions.

Some sources also connect the legendary Faust with Johann Fust (c. 1400–1466), Johann Gutenberg's business partner,[5] or suggest that Fust is one of the multiple origins to the Faust story.[6]

The character in Polish folklore named Pan Twardowski presents similarities with Faust, and this legend seems to have originated at roughly the same time. It is unclear whether the two tales have a common origin or influenced each other. Pan Twardowski may be based on a 16th-century German emigrant to the then-capital of Poland, Kraków, or possibly John Dee or Edward Kelley. According to the theologian Philip Melanchthon, the historic Johann Faust had studied in Kraków, as well.

Related tales about a pact between man and the Devil include the legend of Theophilus of Adana, the 5th-century bishop; and the plays Mary of Nijmegen (Dutch, early 15th century, attributed to Anna Bijns) and Cenodoxus (German, early 17th century, by Jacob Bidermann).

The notes to one edition of Goethe's Faust assert that the alchemists Agrippa and Paracelsus were combined into the protagonist.[citation needed]

Marlowe's Doctor Faustus

The early Faust chapbook, while in circulation in northern Germany, found its way to England, where in 1592 an English translation was published, The Historie of the Damnable Life, and Deserved Death of Doctor Iohn Faustus credited to a certain "P. F., Gent[leman]". Christopher Marlowe used this work as the basis for his more ambitious play, The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus (published c. 1604). Marlowe also borrowed from John Foxe's Book of Martyrs, on the exchanges between Pope Adrian VI and a rival pope. Another possible inspiration of Marlowe's version is John Dee (1527–1609), who practiced forms of alchemy and science and developed Enochian magic.

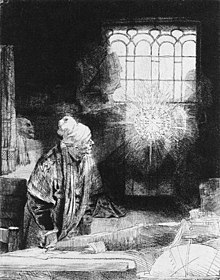

Goethe's Faust

The most important version of the legend is the play Faust by the German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Goethe's Faust complicates the simple Christian moral of the original legend. A hybrid between a play and an extended poem, Goethe's two-part "closet drama" is epic in scope. It gathers together references from Christian, medieval, Roman, eastern and Hellenic poetry, philosophy and literature; ending in a Faust who is saved, carried aloft to heaven, as Mephistopheles looks on.

The composition and refinement of Goethe's own version of the legend occupied him for over 60 years (though not continuously). The final version, published after his death, is recognized as a great work of German literature.

The story concerns the fate of Faust in his quest for the true essence of life ("was die Welt im Innersten zusammenhält"). Frustrated with learning and the limits to his knowledge and power, he attracts the attention of the Devil (represented by Mephistopheles), who agrees to serve Faust until the moment he attains the zenith of human happiness, at which point Mephistopheles may take his soul. Faust is pleased with the deal, as he believes the moment will never come.

In the first part, Mephistopheles leads Faust through experiences that culminate in a lustful relationship with Gretchen, an innocent young woman. Gretchen and her family are destroyed by Mephistopheles' deceptions and Faust's desires. The story ends in tragedy as Gretchen is saved and Faust is left in shame.

The second part begins with the spirits of the earth forgiving Faust (and the rest of mankind) and progresses into allegorical poetry. Faust and his devil pass through the world of politics and the world of the classical gods, and meet with Helen of Troy (the personification of beauty). Finally, having succeeded in taming the very forces of war and nature, Faust experiences a single moment of happiness.

Mephistopheles tries to seize Faust's soul when he dies, but is frustrated when angels intervene, recognizing the value of Faust's unending striving.

Influence

Goethe's Faust was the basis for two major operas: Faust by Charles Gounod and Mefistofele by Arrigo Boito; and for Ferruccio Busoni's opera Doktor Faustus.

It has inspired major musical works in other forms, such as the "dramatic legend" The Damnation of Faust by Hector Berlioz, Robert Schumann's Scenes from Goethe's Faust, the second part of Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 8, and Franz Liszt's Faust Symphony.

Translations into English

In September 2006, Oxford University Press published an English, blank-verse translation of Goethe's work entitled Faustus, From the German of Goethe, now widely believed to be the production of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The translation, which was published anonymously in 1821, was previously attributed to George Soane. Despite this evidence, the status of the translation as the work of Coleridge is still disputed by some Coleridge authorities.[7]

Thomas Mann's Doctor Faustus

Thomas Mann's 1947 Doktor Faustus: Das Leben des deutschen Tonsetzers Adrian Leverkühn, erzählt von einem Freunde adapts the Faust legend to a 20th-century context, documenting the life of fictional composer Adrian Leverkühn as analog and embodiment of the early 20th-century history of Germany and of Europe. The talented Leverkühn, after contracting venereal disease from a brothel visit, forms a pact with a Mephistophelean character to grant him 24 years of brilliance and success as a composer. He produces works of increasing beauty to universal acclaim, even while physical illness begins to corrupt his body. In 1930, when presenting his final masterwork (The Lamentation of Dr Faust), he confesses the pact he had made: madness and syphilis now overcome him, and he suffers a slow and total collapse until his death in 1940. Leverkühn's spiritual, mental, and physical collapse and degradation are mapped on to the period in which Nazism rose in Germany, and Leverkühn's fate is shown as that of the soul of Germany.

See also

- Works based on Faust

- "Solamen miseris socios habuisse doloris", a Latin phrase from Marlowe's play The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus

- Jonathan Moulton, the "Yankee Faust"

- Staufen, Germany, a town in the extreme southwest of Germany, claims to be where Faust died (ca. 1540); depictions appear on buildings, etc. The only historical source for this tradition is a passage in the Chronik der Grafen von Zimmern, which was written around 1565, 25 years after Faust's presumed death. These chronicles are generally considered reliable, and in the 16th century there were still family ties between the lords of Staufen and the counts of Zimmern in nearby Donaueschingen.[8]

- Deal with the Devil

- Cross Road Blues

Notes

- ^ http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Faustian

- ^ "Faust". Encyclopaedia Britannica. New York: The Encyclopaedia Britannica Company. 1910.

- ^ Frank Baron, "Doctor Faustus, from History to Legend" (Wilhelm Fink Verlag: 1978)

- ^ Leo Ruickbie: Faustus: The Life and Times of a Renaissance Magician. The History Press 2009. ISBN 978-0750950909

- ^ Meggs, Philip B. (2006). Meggs' History of Graphic Design, Fourth Edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 73. ISBN 0471699020.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jensen, Eric (Autumn, 1982). "Liszt, Nerval, and "Faust"". 19th-Century Music. 6 (2). University of California Press: 153.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ A review of the controversial edition, Times Literary Supplement, Kelly Grovier

- ^ Geiges, Leif (1981), Faust's Tod in Staufen: Sage - Dokumente. Freiburg im Breisgau: Kehrer Verlag KG

Sources

- Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe, Edited and with an introduction by Sylvan Barnet (1969, Signet Classics)

- J. Scheible, Das Kloster (1840s).

External links

- Faust at Curlie

- BBC Radio 4, In Our Time - Faust

- Faust Study Guide

- The Faust Tradition from Marlowe to Mann, California State University, Chico

- Pacts with the Devil: Faust and Precursors

- E-texts:

- Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at Project Gutenberg

- Tragical History of Dr. Faustus at Project Gutenberg (Quarto of 1604)

- Tragical History of Dr. Faustus at Project Gutenberg (Quarto of 1616)

- Jan Svankmajer's Faust

- The Pre-Death Thoughts of Faust by Nikolai Berdyaev

- A wiki page about Faust. Includes scene by scene commentary.

- Did Coleridge translate Goethe's Faust? An article by Kelly Grovier in the Times Literary Supplement

- For a free public domain copy of the work by Goethe from Project Gutenberg