Hookah: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

====Azerbaijan==== |

====Azerbaijan==== |

||

In the Republic of [[Azerbaijan]] (sometimes reffered to as Northern Azerbaijan), smoking hookah is an ancient tradition, but its popularity decreased during Soviet times. In Azerbaijan it is called Qəlyan, Qəlyanaltı or Nargilə. The strongest effect can be reached by filtering it with milk, vodka or Red Bull (people sometimes mix vodka with milk and vodka with Red Bull). The most popular flavors in Azerbaijan are: Orange, Mint, Bubblegum, Pomegranate and Bahraini apples. While smoking, everyone has his or her personal mouthpiece (locally called "Moushtouk"). Qalyanaltı is usually smoked in tea clubs ("Çayxana"; "Çay evi"; "Çay klubu")or special places called "Qəlyannaya" (from Russian - Кальянная, Hookah Place). |

In the Republic of [[Azerbaijan]] (sometimes reffered to as Northern Azerbaijan), smoking hookah is an ancient tradition, but its popularity decreased during Soviet times. In Azerbaijan it is called Qəlyan, Qəlyanaltı or Nargilə. The strongest effect can be reached by filtering it with milk, vodka or Red Bull (people sometimes mix vodka with milk and vodka with Red Bull). The most popular flavors in Azerbaijan are: Orange, Mint, Bubblegum, Pomegranate and Bahraini apples. While smoking, everyone has his or her personal mouthpiece (locally called "Moushtouk"). Qalyanaltı is usually smoked in tea clubs ("Çayxana"; "Çay evi"; "Çay klubu") or special places called "Qəlyannaya" (from Russian - Кальянная, Hookah Place). |

||

====Iran==== |

====Iran==== |

||

Revision as of 18:30, 7 January 2011

- The homophone Hooka can refer to surface-supplied underwater diving.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2008) |

A hookah (Hindustani: हुक़्क़ा (Devanagari), حقّہ (Nastaleeq) huqqah)[1][2] also known as a waterpipe[3] is a single or multi-stemmed (often glass-based) instrument for smoking in which the smoke is cooled and filtered by passing through water. The tobacco smoked is referred to as shisha or sheesha in the United States and Canada.[4] Originally from India,[1][5][6][7][8][9] hookah has gained popularity, especially in the Middle East and is gaining popularity in North America, Europe and Australia.[2]

Names and etymology

Depending on locality, hookahs or shishas may be referred to by many names: Arabic language uses it as Shisha (شيشة) or Nargeela (نرجيلة) or Argeela (أركيلة\أرجيلة) and they use it throughout the whole of the Arab World; Nargile (but sometimes pronounced Argileh or Argilee) is the name most commonly used in Turkey, Greece, Cyprus, Armenia, Azerbaijan,Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Israel.[citation needed] Nargileh derives from the Persian word nārghile, meaning coconut, which in turn is from the Sanskrit word nārikela (नारिकेला), suggesting that early hookahs were hewn from coconut shells.[10][11]

In Albania, Bosnia, Croatia the hookah is called "Lula" or "Lulava" in Romani, meaning "pipe," the word "shishe" refers to the actual bottle piece.[citation needed]

In Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and in much of the eastern and southern former Yugoslavia, "Nargile" (Наргиле) or "Nagile" (Нагиле) is used to refer to the pipe. "šiša" (шиша) usually refers to the nicotine and tar free tobacco that is smoked in it. The pipes there often have one or two mouth pieces. They are usually shared between two people. The flavored tobacco is placed above the water and covered by pierced foil with hot coals placed on top, the smoke is drawn through cold water to cool and filter it. This, "narguile",[12] is also the common word in Spain, where hookah is also referred to as "cachimba",[13] though Moroccan immigrants in Spain use the word "shisha".

Shisha (شيشة), from the Persian word shīshe (شیشه), meaning glass, is the common term for the hookah in Egypt and the Arab countries of the Persian Gulf (including Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, UAE, and Saudi Arabia), and in Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Somalia and Yemen.

In Iran, hookah is called قلیان "ḡalyān". The name of the implement for smoking, ḡalyān, was apparently derived from the Ar. √ḡlā (to boil, bubble up) which is believed, it was the first name of Hookah too. This is also the name used in Ukraine, Russia and Belarus, where hookah bars enjoy a great deal of popularity.

In Uzbekistan, hookah is called "Chillim". In India and Pakistan the name most similar to the English hookah is used: huqqa (हुक़्क़ा /حقّہ).[citation needed]

In Maldives, hookah is called "Gudugudaa".[citation needed]

The commonness of the Indian word "hookah" in English is a result of the British Raj, the British dominion of India (1858–1947), when large numbers of expatriate Britons first sampled the water-pipe. William Hickey, shortly after arriving in Kolkata, India, in 1775, wrote in his Memoirs:

The most highly-dressed and splendid hookah was prepared for me. I tried it, but did not like it. As after several trials I still found it disagreeable, I with much gravity requested to know whether it was indispensably necessary that I should become a smoker, which was answered with equal gravity, "Undoubtedly it is, for you might as well be out of the world as out of the fashion. Here everybody uses a hookah, and it is impossible to get on without" [... I] have frequently heard men declare they would much rather be deprived of their dinner than their hookah.

— [14]

History

The origin of Hookah smoking can be dated millennia back and its initial traces have been found in the North Western provinces of India alongside the border of Pakistan in the state of Rajasthan and Gujarat. According to Cyril Elgood (PP.41, 110) who does not mention his source, it was in India where Hakim Abu’l-Fatḥ Gīlānī (d. 1588), an Iranian physician at the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar I (1542 - 1605 AD) invented the idea.[15][16][17] Following the European introduction of tobacco to India, Hakim Abul Fateh Gilani a descendant of Abdul-Qadir Gilani came from Gilan, a province in the north of Iran, to India. He later became a physician in the court of Mughal and raised concerns after smoking tobacco became popular among Indian noblemen. He subsequently envisaged a system which allowed smoke to be passed through water in order to be 'purified'.[15] Gilani introduced the ḡalyān after Asad Beg, the ambassador of Bijapur, encouraged Akbar to take up smoking.[15] Following popularity among noblemen, this new device for smoking soon became a status symbol for the Indian aristocracy and gentry.[15][17]

In North India, it is a great tradition followed among Gurjars, Jats, Bishnois, Rajputs etc. However, a quatrain of Ahlī Šīrāzī (d. 1535), a Persian poem, refers to the use of the ḡalyān (Falsafī, II, p. 277; Semsār, 1963, p. 15), thus dating its use at least as early as the time of Shah Ṭahmāsp I. It seems, therefore, that Abu’l-Fatḥ Gīlānī should be credited with the introduction of the ḡalyān, already in use in Persia, to India. The hookah pipe is also known as the Marra pipe in the UK, especially in the North East, where it is used for recreational purposes.

Culture

Middle East

Arab world

In the Arab world, people smoke it as part of their culture and traditions. Social smoking is done with a single or double hose, and sometimes even more numerous such as a triple or quadruple hose in the forms of parties or small get-togethers. When the smoker is finished, either the hose is placed back on the table signifying that it is available, or it is handed from one user to the next, folded back on itself so that the mouthpiece is not pointing at the recipient.

Most cafés (Arabic: مقهىً, transliteration: maqhah, translation: coffeeshop) in the Middle East offer shishas.[citation needed] Cafés are widespread and are amongst the chief social gathering places in the Arab world (akin to public houses in Britain).[citation needed] Some expatriate Britons arriving in the Middle East adopt shisha cafés to make up for the lack of pubs in the region, especially where prohibition is in place.

Azerbaijan

In the Republic of Azerbaijan (sometimes reffered to as Northern Azerbaijan), smoking hookah is an ancient tradition, but its popularity decreased during Soviet times. In Azerbaijan it is called Qəlyan, Qəlyanaltı or Nargilə. The strongest effect can be reached by filtering it with milk, vodka or Red Bull (people sometimes mix vodka with milk and vodka with Red Bull). The most popular flavors in Azerbaijan are: Orange, Mint, Bubblegum, Pomegranate and Bahraini apples. While smoking, everyone has his or her personal mouthpiece (locally called "Moushtouk"). Qalyanaltı is usually smoked in tea clubs ("Çayxana"; "Çay evi"; "Çay klubu") or special places called "Qəlyannaya" (from Russian - Кальянная, Hookah Place).

Iran

In Iran, the hookah is known as a ḠALYĀN (Persian: قليان, قالیون, غلیون, also spelled ghalyan, ghalyaan or ghelyoon). It is similar in many ways to the Arabic hookah but has its own unique attributes. An example is the top part of the ghalyoun called 'sar' (Persian: سر=head), where the tobacco is placed, is bigger than the ones seen in Turkey. Also the major part of the hose is flexible and covered with soft silk or cloth while the Turkish make the wooden part as big as the flexible part.[citation needed]

Each person has his own personal mouthpiece (called an Amjid) (امجید), Amjid is usually made of wood or metal and decorated with valuable or other stones.[citation needed] Amjids are only used for their fancy look. However, all the Hookah Bars have plastic mouth-pieces.[citation needed]

The exact date of the first use of ḡalyān in Persia is not known. According to Cyril Elgood (pp. 41, 110), who does not mention his source, it wasAbu’l-Fatḥ Gīlānī (d. 1588), a Persian physician at the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar I, who “first passed the smoke of tobacco through a small bowl of water to purify and cool the smoke and thus invented the hubble-bubble or hookah.” However, a quatrain of Ahlī Šīrāzī (d. 1535) refers to the use of the ḡalyān (Falsafī, II, p. 277; Semsār, 1963, p. 15), thus dating its use at least as early as the time of Ṭahmāsp I (1524–76). It seems, therefore, that Abu’l-Fatḥ Gīlānī should be credited with the introduction of the ḡalyān, already in use in Persia, to India.

Although the Safavid Shah ʿAbbās I strongly condemned tobacco use, towards the end of his reign smoking ḡalyān and čopoq (q.v.) had become common on every level of the society, women included. In schools and learned circles, both teachers and students had ḡalyāns while lessons continued (Falsafī, II, pp. 278–80). Shah Ṣafī (r. 1629-42) declared a complete ban on tobacco, but the income received from its use persuaded him to revoke the ban. The use of ḡalyāns became so widespread that a group of poor people became professional tinkers of crystal water pipes. During the time of Shah ʿAbbās II (r. 1642-1666), use of the water pipe had become a national addiction (Chardin, tr., II, p. 899). The shah had his own private ḡalyān servant. Evidently the position of water pipe tender (ḡalyāndār) dates from this time. Also at this time, reservoirs were made of glass, pottery, or a type of gourd. Because of the unsatisfactory quality of indigenous glass, glass reservoirs were sometimes imported from Venice (Chardin, tr., II, p. 892). In the time of Shah Solaymān (r. 1694-1722), ḡalyāns became more elaborately embellished as their use increased. The wealthy owned gold and silver pipes. The masses spent more on ḡalyāns than they did on the necessities of life (Tavernier apud Semsār, 1963, p. 16). An emissary of Shah Solṭān Ḥosayn (r.1722-32) to the court of Louis XIV, on his way to the royal audience at Versailles, had in his retinue an officer holding his ḡalyān, which he used while his carriage was in motion (Herbette, tr. p. 7; Kasrawī, pp. 211–12; Semsār, 1963, pp. 18–19). We have no record indicating the use of ḡalyān at the court of Nāder Shah Afšār, although its use seems to have continued uninterrupted. There are portraits of Karīm Khan Zand and Fatḥ-ʿAlī Shah Qājār which depict them smoking the ḡalyān.[18] Iranians had a special tobacco called Khansar (خانسار, presumably name of the origin city). The charcoals would be put on the Khansar without foil. Khansar has less smoke than the normal tobacco. Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar, Shah of Persia (1848–1896) is reputed to have considered a hookah mouthpiece pointed at him an insult.[citation needed]

The smoking of hookahs is very popular with young people in Iran, and many young people can be seen smoking them in local tea shops.[citation needed]

The hookah was, until recently, served to all ages; Iranian officials have since passed a law forbidding its use by those under 20.[citation needed]

Israel

The Israeli term for hookah is nargila (Hebrew: נרגילה).

South Asia

Pakistan

In Pakistan, although traditionally prevalent in rural areas for generations,[19] hookahs have become very popular in the cosmopolitan cities. Many clubs and cafes are offering them and it has become quite popular amongst the youth and students in Pakistan. This form of smoking has become very popular for social gatherings, functions, and events. There are a large number of cafes and restaurants offering a variety of hookahs. Karachi has seen a growth in this business. Now Islamabad also prospers by this trade.

India

The concept of hookah originated In India,[20] once the province of the wealthy, it was tremendously popular especially during Mughal rule. The hookah has since become less popular; however, it is once again garnering the attention of the masses, and cafés and restaurants that offer it as a consumable are popular. The use of hookahs from ancient times in India was not only a custom, but a matter of prestige. Rich and landed classes would smoke hookahs.

Tobacco is smoked in hookahs in many villages as per traditional customs. Smoking a tobacco-molasses shisha is now becoming popular amongst the youth in India. There are several chain clubs, bars and coffee shops in India offering a wider variety of mu‘assels, including non-tobacco versions.

Koyilandy, a small fishing town on the west coast of India, once made and exported hookahs extensively. These are known as Malabar Hookhas or Koyilandy Hookahs. Today these intricate hookahs are difficult to find outside of Koyilandy and not much easier to find in Koyilandy itself.

As hookah makes a resurgence in India, there have been numerous raids and bans recently on hookah smoking, especially in Gujarat[21]

Bangladesh

The terms Hookah and Shisha are used in Bangladesh. While simple, wooden Hookahs are popular around the country, the popularity of Shisha as a party drug and at Hookah lounges has increased in recent years in major cities. Can be found in various flavors of tobacco.

Southeast Asia

Philippines

In the Philippines, the Hookah or Shisha was particularly used within the minority Arab Filipino communities and Indian Filipino, although particularly among indigenous Muslim Filipinos, a historical following of social and cultural trends set in the Middle East led to the Hookah being a rare albeit prestige social-habit of noblemen in important trade cities such as Cotabato or Jolo.

Hookah was virtually unknown by Christian Filipinos before the latter 20th century, yet the popularity among contemporary younger Christians is now vastly growing. In the capital's most cosmopolitan city, Makati; various high-end bars and clubs offer hookahs to patrons.

Although hookah use has been common for hundreds of years and enjoyed by people of all ages, it has just begun to become a youth-oriented pastime in Asia in recent times. Hookahs are most popular with college students and young adults, who may be underage and thus unable to purchase cigarettes.[22]

South Africa

In South Africa, hookah, colloquially known as a hubbly bubbly or an okka pipe, is popular amongst the Cape Malay and Indian populations, wherein it is smoked as a social pastime.[23] However, hookah is seeing increasing popularity with white South Africans, especially the youth. Bars that additionally provide hookahs are becoming more prominent, although smoking is normally done at home or in public spaces such as beaches and picnic sites.

In South Africa, the terminology of the various hookah components also differ from other countries. The clay "head/bowl" is known as a "clay pot". The hoses are called "pipes" and the air release valve is known, strangely, as a "clutch".

Some scientists point to the dagga pipe as an African origin of hookah.[24]

United States and Canada

Many who were teens and young adults in the 1960s and 1970s will be familiar with the hookah as a variety of waterpipe used to consume various derivations of marijuana.[citation needed] At parties or small gatherings the hookah hose was passed around with users partaking as they saw fit.

Recently many cities, states and counties have implemented indoor smoking bans. In some jurisdictions, hookah businesses can be exempted from the policies through special permits. Some permits however, have requirements such as the business earning a certain minimum percentage of their revenue from alcohol or tobacco.

In cities with indoor smoking bans, hookah bars have been forced to close or switch to tobacco-free mu‘assel. In many cities though, hookah lounges have been growing in popularity. From the year 2000 to 2004, over 200 new hookah cafes opened for business, most of which are targeted at a young-adult age group,[25] and were particularly near college campuses or cities with large Middle-Eastern communities. This activity continues to grow in popularity within the post-secondary student demographic[citation needed] .

Structure and operation

Components

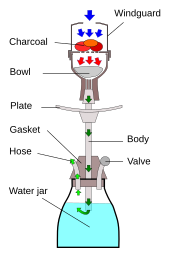

Excluding grommets, a hookah consists of a number of components, four of which are essential for its operation.

Bowl

Also known as the head of the hookah, the bowl is a container, usually made out of clay or marble, that holds the coal and tobacco during the smoking session. The bowl is loaded with tobacco then covered in a small piece of perforated aluminum foil or a glass or metal screen. Lit coals are then placed on top, which allows the tobacco to heat to the proper temperature.

There is also a variation of the head which employs a fruit rather than the traditional clay bowl. The fruit is hollowed out and perforated in order to achieve the same shape and system a clay bowl has, then it is loaded and used in the same manner.

Bowls have evolved over the past two years to incorporate new designs that keep juices in the tobacco from running down the stem. The Tangiers Phunnel Bowl and Sahara Smoke Vortex Bowl are two examples of such bowls.

Windscreen

A Hookah Cover windscreen is a cover which sits over the bowl area, with some form of air holes. This prevents wind from increasing the burn rate and temperature of the coal, and prevents ash and burning embers from being blown onto the surrounding environment. This may also offer some limited protection from fire as it may prevent the coal from being ejected if the hookah is bumped.

Hose

Technically if the pipe has a hose it is not "hookah"—the term historically referred to a straight-neck tube. Today the hose (one or more) is a slender flexible tube that allows the smoke to be drawn for a distance, cooling down before inhalation. The end is typically fitted with a metal, wooden, or plastic mouthpiece of various shape, size, color or material type.

Purge valve

Many hookah are equipped with a purge valve connected to the airspace in the water jar to purge stale smoke which has been sitting unused in the jar for too long. This one-way valve is typically a simple ball bearing sitting over a port which seals the port by gravity alone and will open if positive pressure is created by blowing into the hose. The bearing will be held captive with a screw-on cover. The cover should be opened and the bearing and seat cleaned of residue and corrosion regularly to ensure proper sealing.

Water jar

The body of the hookah sits on top of the water jar. The downstem hangs down below the level of the water in the jar. Smoke passes through the body and out the downstem where it bubbles through the water. This cools and humidifies the smoke. Liquids such as fruit juice may be added to the water or used in substitution. Pieces of fruit, mint leaves, and crushed ice may be added.

Plate

A plate or ashtray sits just below the bowl to catch ashes falling off the coals.

Grommets

Grommets in a hookah are usually placed between the bowl and the body, the body's gasket and the water jar and between the body and the hose. The grommets, although not essential (the use of paper or tape has become common), will help to seal the joints between the parts, therefore decreasing the amount of air coming in and maximizing the smoke breathed in.

Diffuser

the smoke-filtering process, creating a cleaner smoke and a subdued noise. It is used as a luxury item for a premium smoking experience and is not a required component.

Operation

The jar at the bottom of the hookah is filled with water sufficient to submerge a few centimeters of the body tube, which is sealed tightly to it. Deeper water will only increase the inhalation force needed to use it. Tobacco is placed inside the bowl at the top of the hookah and then a foil or charcoal screen with a burning charcoal is placed on top. Some cultures cover the bowl with perforated tin foil or a metal screen to separate the coal and the tobacco, which minimizes inhalation of coal ash with the smoke. This may also reduce the temperature the tobacco is exposed to, in order to prevent burning the tobacco directly.

When one inhales through the hose, air is pulled through the charcoal and into the bowl holding the tobacco. The hot air, heated by the charcoal vaporizes (not burns) the tobacco, thus producing smoke, which is passed down through the body tube that extends into the water in the jar. It bubbles up through the water, losing heat, and fills the top part of the jar, to which the hose is attached. When a smoker inhales from the hose, smoke passes into the lungs, and the change in pressure in the jar pulls more air through the charcoal, continuing the process.

If the hookah has been lit and smoked but has not been inhaled for an extended period, the smoke inside the water jar may be regarded as "stale" and undesirable. Stale smoke may be exhausted through the purge valve, if present. This one-way valve is opened by the positive pressure created from gently blowing into the hose. It will not function on a multiple-hose hookah unless all other hoses are plugged. Sometimes one-way valves are put in the hose sockets to avoid the need to manually plug hoses.

Health effects

Although the use of Hookah has been commonly attributed to be much worse than regular tobacco smoke, tests remain inconclusive as to the true health impact of the hookah. Some studies conclude that Hookah smoke is safer than tobacco cigarette smoke,[26] while other studies refute this claim.

Each hookah session typically lasts more than 40 minutes, and consists of 50 to 200 inhalations that each range from 0.15 to 0.50 liters of smoke.[27][28] In an hour-long smoking session of hookah, users consume about 100 to 200 times the smoke of a single cigarette;[27] in a 45-minute smoking session a typical smoker would inhale 1.7 times the nicotine [29] of a single cigarette. The water used to filter the smoke does not remove all the harmful chemicals.[29]

A study on hookah smoking and cancer in Pakistan was published in 2008.[26] Its objective was "to find serum CEA levels in ever/exclusive hookah smokers, i.e. those who smoked only hookah (no cigarettes, bidis, etc.)." Levels in exclusive hookah smokers were lower compared to cigarette smokers although the difference was not statistically significant between a hookah smoker and a non-smoker. The study also concluded that heavy hookah smoking (2–4 daily preparations; 3–8 sessions a day; 2 to 6 hours) substantially raises CEA levels.

References

- ^ a b The cyclopaedia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, Volume 2. Bernard Quaritch. 1885. Retrieved 2007–08–01.

HOOKAH. Hindi. The Indian pipe and apparatus for smoking.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "Hookah". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation (TobReg) an advisory note "Waterpipe tobacco smoking:health effects, research needs and recommended actions by regulators", 2005

- ^ "The History and Mystery of Tobacco". Harper's. June 1855.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ The Wealth of India. Council of Scientific & Industrial Research. 1976. Retrieved 2007–08–01.

The smoking of hookah and hubble-bubble started in India during the reign of the great Moghul emperor, Akbar.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Beyond the Smoke, There is Solidarity Among Cultures". Victoria Harben for Common Ground News Service. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ^ "Metro Detroit's Hookah Scene". Terry Parris Jr for Metromode Media. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ^ "Hookah History". Colors of India. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ^ Rousselet, Louis (2005) [1875]. "XXVII - The Ruins of Futtehpore". India and Its Native Princes: Travels in Central India and in the Presidencies of Bombay and Bengal (in English - UK) (Reprint - Asian Educational Services 2005 ed.). London: Chapman and Hall. p. 290. ISBN 8-1206-1887-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Nargile". mymerhaba.

- ^ "Smoke like an Egyptian - Sri Lanka". Lankanewspapers.com. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "Diccionario de la lengua española - Vigésima segunda edición" (in Template:Es icon). Buscon.rae.es. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Diccionario de la lengua española - Vigésima segunda edición" (in Template:Es icon). Buscon.rae.es. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Memoirs of William Hickey (Volume II ed.). London: Hurst & Blackett. 1918. p. 136.

- ^ a b c d Sivaramakrishnan, V. M. (2001). Tobacco and Areca Nut. Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan. pp. 4–5. ISBN 8125020136.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Blechynden, Kathleen (1905). Calcutta, Past and Present. Los Angeles: University of California. p. 215.

- ^ a b Rousselet, Louis (1875). India and Its Native Princes: Travels in Central India and in the Presidencies of Bombay and Bengal. London: Chapman and Hall. p. 290.

- ^ "Encyclopædia Iranica | Articles". Iranica.com. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "Full text | Hookah smoking and cancer: carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels in exclusive/ever hookah smokers". Harm Reduction Journal. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "Origins". Article Niche History of Hookah.

- ^ "Hookah". Indian Express. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- ^ "Use of Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Among Students Aged 13-15 Years - Worldwide, 1999-2005". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Independent Online. "Hubble-bubble as cafes go up in smoke". Iol.co.za. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "The Mysterious Origins of the Hookah (Narghile) The Sacred Narghile

- ^ Lyon, Lindsay "The Hazard in Hookah Smoke". (28 January 2008)

- ^ a b "Hookah smoking and cancer: carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels in exclusive/ever hookah smokers". Harm Reduction Journal. May 24, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Alan Shihadeh, Sima Azar, Charbel Antonios, Antoine Haddad (September, 2004). "Towards a topographical model of narghile water-pipe café smoking: a pilot study in a high socioeconomic status neighbourhood of Beirut, Lebanon". Elsevier Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, Volume 79, Issue 1. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2004.06.005.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mirjana V. Djordjevic, Steven D. Stellman, Edith Zang (January 19, 2000). "Doses of Nicotine and Lung Carcinogens Delivered to Cigarette Smokers". Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Vol. 92, No. 2. doi:10.1093/jnci/92.2.106.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "WHO warns the hookah may pose same risk as cigarettes". USA Today. May 29, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

- The Sacred Narghile, a site containing transdisciplinary anthropological (including on origins) and biomedical information and discussions of the above cited scientific studies

- WHO Report on water pipe (hookah), by WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation (TobReg).

- Critique of the WHO Report on water pipe (hookah) by Chaouachi Kamal. A Critique of WHO's TobReg "Advisory Note" titled: "Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: Health Effects, Research Needs and Recommended Actions by Regulators. Journal of Negative Results in Biomedicine 2006 (17 Nov); 5:17 (Highly Accessed)

- Scientific Evidence of the Health Risks of Hookah Smoking (University of Maryland, College Park: June 9, 2008, vol 17, issue 23