Butterfly effect: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Other uses}} |

{{Other uses}} |

||

{{main| chaos theory}} |

|||

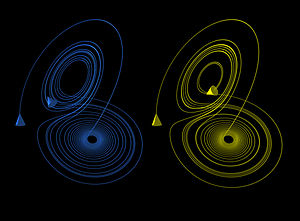

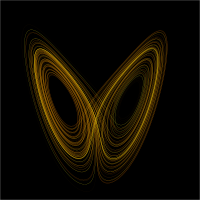

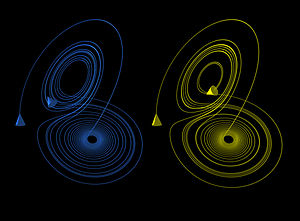

[[Image:Lorenz attractor yb.svg|thumb|200px|right||A plot of Lorenz's [[strange attractor]] for values ρ=28, σ = 10, β = 8/3. The butterfly effect or sensitive dependence on initial conditions is the property of a [[dynamical system]] that, starting from any of various arbitrarily close alternative [[initial condition]]s on the attractor, the [[iteration#mathematics|iterated points]] will become arbitrarily spread out from each other.]] |

[[Image:Lorenz attractor yb.svg|thumb|200px|right||A plot of Lorenz's [[strange attractor]] for values ρ=28, σ = 10, β = 8/3. The butterfly effect or sensitive dependence on initial conditions is the property of a [[dynamical system]] that, starting from any of various arbitrarily close alternative [[initial condition]]s on the attractor, the [[iteration#mathematics|iterated points]] will become arbitrarily spread out from each other.]] |

||

Revision as of 15:11, 10 February 2016

The Butterfly Effect is a concept that small causes can have large effects. Initially, it was used with weather prediction but later the term became a metaphor used in and out of science.[1]

In chaos theory, the butterfly effect is the sensitive dependence on initial conditions in which a small change in one state of a deterministic nonlinear system can result in large differences in a later state. The name, coined by Edward Lorenz for the effect which had been known long before, is derived from the metaphorical example of the details of a hurricane (exact time of formation, exact path taken) being influenced by minor perturbations such as the flapping of the wings of a distant butterfly several weeks earlier. Lorenz discovered the effect when he observed that runs of his weather model with initial condition data that was rounded in a seemingly inconsequential manner would fail to reproduce the results of runs with the unrounded initial condition data. A very small change in initial conditions had created a significantly different outcome.

The idea, that small causes may have large effects in general and in weather specifically, was used from Henri Poincaré to Norbert Wiener. Edward Lorenz's work developed the concept of instability of the atmosphere to a quantitative foundation and linked the concept to the properties of large classes of systems undergoing nonlineardynamics and deterministic chaos theory.[1]

The butterfly effect is exhibited by very simple systems. For example, the randomness of the outcomes of throwing dice depends on this characteristic to amplify small differences in initial conditions—the precise direction, thrust, and orientation of the throw—into significantly different dice paths and outcomes, which makes it virtually impossible to throw dice exactly the same way twice.

History

Chaos theory and the sensitive dependence on initial conditions were described in the literature in a particular case of the three-body problem by Henri Poincaré in 1890.[2] He later proposed that such phenomena could be common, for example, in meteorology.[3]

In 1898,[2] Jacques Hadamard noted general divergence of trajectories in spaces of negative curvature. Pierre Duhem discussed the possible general significance of this in 1908.[2] The idea that one butterfly could eventually have a far-reaching ripple effect on subsequent historic events made its earliest known appearance in "A Sound of Thunder", a 1952 short story by Ray Bradbury about time travel (see Literature and print here).

In 1961, Lorenz was running a numerical computer model to redo a weather prediction from the middle of the previous run as a shortcut. He entered the initial condition 0.506 from the printout instead of entering the full precision 0.506127 value. The result was a completely different weather scenario.[4] In 1963 Lorenz published a theoretical study of this effect in a highly cited, seminal paper called Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow[5][6] (the calculations were performed on a Royal McBee LGP-30 computer).[7][8] Elsewhere he stated:

One meteorologist remarked that if the theory were correct, one flap of a sea gull's wings would be enough to alter the course of the weather forever. The controversy has not yet been settled, but the most recent evidence seems to favor the sea gulls.[8]

Following suggestions from colleagues, in later speeches and papers Lorenz used the more poetic butterfly. According to Lorenz, when he failed to provide a title for a talk he was to present at the 139th meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1972, Philip Merilees concocted Does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas? as a title.[9] Although a butterfly flapping its wings has remained constant in the expression of this concept, the location of the butterfly, the consequences, and the location of the consequences have varied widely.[10]

The phrase refers to the idea that a butterfly's wings might create tiny changes in the atmosphere that may ultimately alter the path of a tornado or delay, accelerate or even prevent the occurrence of a tornado in another location. The butterfly does not power or directly create the tornado, but the term is intended to imply that the flap of the butterfly's wings can cause the tornado: in the sense that the flap of the wings is a part of the initial conditions; one set of conditions leads to a tornado while the other set of conditions doesn't. The flapping wing represents a small change in the initial condition of the system, which cascades to large-scale alterations of events (compare: domino effect). Had the butterfly not flapped its wings, the trajectory of the system might have been vastly different—but it's also equally possible that the set of conditions without the butterfly flapping its wings is the set that leads to a tornado.

The butterfly effect presents an obvious challenge to prediction, since initial conditions for a system such as the weather can never be known to complete accuracy. This problem motivated the development of ensemble forecasting, in which a number of forecasts are made from perturbed initial conditions.[11]

Some scientists have since argued that the weather system is not as sensitive to initial condition as previously believed.[12] David Orrell argues that the major contributor to weather forecast error is model error, with sensitivity to initial conditions playing a relatively small role.[13][14] Stephen Wolfram also notes that the Lorenz equations are highly simplified and do not contain terms that represent viscous effects; he believes that these terms would tend to damp out small perturbations.[15]

Illustration

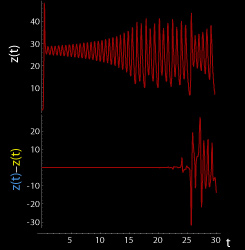

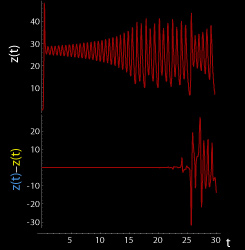

The butterfly effect in the Lorenz attractor time 0 ≤ t ≤ 30 (larger) z coordinate (larger)

These figures show two segments of the three-dimensional evolution of two trajectories (one in blue, the other in yellow) for the same period of time in the Lorenz attractor starting at two initial points that differ by only 10−5 in the x-coordinate. Initially, the two trajectories seem coincident, as indicated by the small difference between the z coordinate of the blue and yellow trajectories, but for t > 23 the difference is as large as the value of the trajectory. The final position of the cones indicates that the two trajectories are no longer coincident at t = 30. An animation of the Lorenz attractor shows the continuous evolution.

Theory and mathematical definition

Recurrence, the approximate return of a system towards its initial conditions, together with sensitive dependence on initial conditions, are the two main ingredients for chaotic motion. They have the practical consequence of making complex systems, such as the weather, difficult to predict past a certain time range (approximately a week in the case of weather) since it is impossible to measure the starting atmospheric conditions completely accurately.

A dynamical system displays sensitive dependence on initial conditions if points arbitrarily close together separate over time at an exponential rate. The definition is not topological, but essentially metrical.

If M is the state space for the map , then displays sensitive dependence to initial conditions if for any x in M and any δ > 0, there are y in M, with distance d(. , .) such that and such that

for some positive parameter a. The definition does not require that all points from a neighborhood separate from the base point x, but it requires one positive Lyapunov exponent.

The simplest mathematical framework exhibiting sensitive dependence on initial conditions is provided by a particular parametrization of the logistic map:

which, unlike most chaotic maps, has a closed-form solution:

where the initial condition parameter is given by . For rational , after a finite number of iterations maps into a periodic sequence. But almost all are irrational, and, for irrational , never repeats itself – it is non-periodic. This solution equation clearly demonstrates the two key features of chaos – stretching and folding: the factor 2n shows the exponential growth of stretching, which results in sensitive dependence on initial conditions (the butterfly effect), while the squared sine function keeps folded within the range [0, 1].

Examples

The butterfly effect is most familiar in terms of weather; it can easily be demonstrated in standard weather prediction models, for example.[16]

The potential for sensitive dependence on initial conditions (the butterfly effect) has been studied in a number of cases in semiclassical and quantum physics including atoms in strong fields and the anisotropic Kepler problem.[17][18] Some authors have argued that extreme (exponential) dependence on initial conditions is not expected in pure quantum treatments;[19][20] however, the sensitive dependence on initial conditions demonstrated in classical motion is included in the semiclassical treatments developed by Martin Gutzwiller[21] and Delos and co-workers.[22]

Other authors suggest that the butterfly effect can be observed in quantum systems. Karkuszewski et al. consider the time evolution of quantum systems which have slightly different Hamiltonians. They investigate the level of sensitivity of quantum systems to small changes in their given Hamiltonians.[23] Poulin et al. presented a quantum algorithm to measure fidelity decay, which "measures the rate at which identical initial states diverge when subjected to slightly different dynamics". They consider fidelity decay to be "the closest quantum analog to the (purely classical) butterfly effect".[24] Whereas the classical butterfly effect considers the effect of a small change in the position and/or velocity of an object in a given Hamiltonian system, the quantum butterfly effect considers the effect of a small change in the Hamiltonian system with a given initial position and velocity.[25][26] This quantum butterfly effect has been demonstrated experimentally.[27] Quantum and semiclassical treatments of system sensitivity to initial conditions are known as quantum chaos.[19][25]

See also

- Actuality and potentiality

- Avalanche effect

- Behavioral cusp

- Butterfly effect in popular culture

- Cascading failure

- Causality

- Chain reaction

- Clapotis

- Determinism

- Domino effect

- Dynamical systems

- Fractal

- Great Stirrup Controversy

- Innovation butterfly

- Kessler syndrome

- Law of unintended consequences

- Point of divergence

- Positive feedback

- Representativeness heuristic

- Ripple effect

- Snowball effect

- Traffic congestion

- Tropical cyclogenesis

References

- ^ a b "Butterfly effect - Scholarpedia". www.scholarpedia.org. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ^ a b c Some Historical Notes: History of Chaos Theory

- ^ Steves, Bonnie; Maciejewski, AJ (September 2001). The Restless Universe Applications of Gravitational N-Body Dynamics to Planetary Stellar and Galactic Systems. USA: CRC Press. ISBN 0750308222. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ Gleick, James (1987). Chaos: Making a New Science. Viking. p. 16. ISBN 0-8133-4085-3.

- ^ Lorenz, Edward N. (March 1963). "Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 20 (2): 130–141. Bibcode:1963JAtS...20..130L. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1963)020<0130:DNF>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0469. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- ^ Google Scholar citation record

- ^ "Part19". Cs.ualberta.ca. 1960-11-22. Retrieved 2014-06-08.

- ^ a b Lorenz, Edward N. (1963). "The Predictability of Hydrodynamic Flow" (PDF). Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences. 25 (4): 409–432. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Lorenz: "Predictability", AAAS 139th meeting, 1972 Retrieved May 22, 2015

- ^ "The Butterfly Effects: Variations on a Meme". AP42 ...and everything. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ Woods, Austin (2005). Medium-range weather prediction: The European approach; The story of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts. New York: Springer. p. 118. ISBN 978-0387269283.

- ^ Orrell, David; Smith, Leonard; Barkmeijer, Jan; Palmer, Tim (2001). "Model error in weather forecasting". Nonlinear Proc. Geoph. 9: 357–371.

- ^ Orrell, David (2002). "Role of the metric in forecast error growth: How chaotic is the weather?". Tellus. 54A: 350–362. doi:10.3402/tellusa.v54i4.12159.

- ^ Orrell, David (2012). Truth or Beauty: Science and the Quest for Order. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-0300186611.

- ^ Wolfram, Stephen (2002). A New Kind of Science. Wolfram Media. p. 998. ISBN 978-1579550080.

- ^ "Chaos and Climate". RealClimate. Retrieved 2014-06-08.

- ^ Heller, E. J.; Tomsovic, S. (July 1993). "Postmodern Quantum Mechanics". Physics Today. 46: 38. Bibcode:1993PhT....46g..38H. doi:10.1063/1.881358.

- ^ Gutzwiller, Martin C. (1990). Chaos in Classical and Quantum Mechanics. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-97173-4.

- ^ a b Rudnick, Ze'ev (January 2008). "What is...Quantum Chaos" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society.

- ^ Berry, Michael (1989). "Quantum chaology, not quantum chaos". Physica Scripta. 40 (3): 335–336. Bibcode:1989PhyS...40..335B. doi:10.1088/0031-8949/40/3/013.

- ^ Gutzwiller, Martin C. (1971). "Periodic Orbits and Classical Quantization Conditions". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 12 (3): 343. Bibcode:1971JMP....12..343G. doi:10.1063/1.1665596.

- ^ Gao, J.; Delos, J. B. (1992). "Closed-orbit theory of oscillations in atomic photoabsorption cross sections in a strong electric field. II. Derivation of formulas". Phys. Rev. A. 46 (3): 1455–1467. Bibcode:1992PhRvA..46.1455G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.46.1455.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Karkuszewski, Zbyszek P.; Jarzynski, Christopher; Zurek, Wojciech H. (2002). "Quantum Chaotic Environments, the Butterfly Effect, and Decoherence". Physical Review Letters. 89 (17): 170405. arXiv:quant-ph/0111002. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..89q0405K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.170405.

- ^ Poulin, David; Blume-Kohout, Robin; Laflamme, Raymond; Ollivier, Harold (2004). "Exponential Speedup with a Single Bit of Quantum Information: Measuring the Average Fidelity Decay". Physical Review Letters. 92 (17): 177906. arXiv:quant-ph/0310038. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..92q7906P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.177906. PMID 15169196.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Poulin, David. "A Rough Guide to Quantum Chaos" (PDF).

- ^ Peres, A. (1995). Quantum Theory: Concepts and Methods. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

- ^ Lee, Jae-Seung; Khitrin, A. K. (2004). "Quantum amplifier: Measurement with entangled spins". Journal of Chemical Physics. 121 (9): 3949. Bibcode:2004JChPh.121.3949L. doi:10.1063/1.1788661.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- James Gleick, Chaos: Making a New Science, New York: Viking, 1987. 368 pp.

- Devaney, Robert L. (2003). Introduction to Chaotic Dynamical Systems. Westview Press. ISBN 0670811785.

- Hilborn, Robert C. (2004). "Sea gulls, butterflies, and grasshoppers: A brief history of the butterfly effect in nonlinear dynamics". American Journal of Physics. 72 (4): 425–427. Bibcode:2004AmJPh..72..425H. doi:10.1119/1.1636492.

External links

- The meaning of the butterfly: Why pop culture loves the 'butterfly effect,' and gets it totally wrong, Peter Dizikes, Boston Globe, June 8, 2008

- New England Complex Systems Institute - Concepts: Butterfly Effect

- The Chaos Hypertextbook. An introductory primer on chaos and fractals

- ChaosBook.org. Advanced graduate textbook on chaos (no fractals)

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Butterfly Effect". MathWorld.