First Opium War: Difference between revisions

Mr Stephen (talk | contribs) →Aftermath: clean up, replaced unicode 00A0→' '(2) using AWB |

Rescuing 2 sources and tagging 1 as dead. #IABot (v1.4beta) (TheDragonFire) |

||

| Line 199: | Line 199: | ||

The Treaty of Nanking, the Supplementary Treaty of the Bogue, and two French and American agreements were all "unequal treaties" signed between 1842 and 1844. The terms of these treaties undermined China's traditional mechanisms of foreign relations and methods of controlled trade. Five ports were opened for trade, gunboats, and foreign residence: Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai. Hong Kong was seized by the British to become a free and open port. Tariffs were abolished thus preventing the Chinese from raising future duties to protect domestic industries and extraterritorial practices exempted Westerners from Chinese law. This made them subject to their own civil and criminal laws of their home country. Most importantly, the opium problem was never addressed and after the treaty was signed opium addiction doubled. China was forced to pay 21 million silver [[tael]]s as an indemnity, which was used to pay compensation for the traders' opium destroyed by Commissioner Lin. A couple of years after the treaties were signed internal rebellion began to threaten foreign trade. Due to the Qing government's inability to control collection of taxes on imported goods, the British government convinced the Manchu court to allow Westerners to partake in government official affairs. By the 1850s the [[Chinese Maritime Customs Service]], one of the most important bureaucracies in the Manchu Government, was partially staffed and managed by Western Foreigners.<ref name="Sharpe"/> In 1858 opium was legalised, and would remain a problem<ref>Miron, Jeffrey A. and Feige, Chris. The Opium Wars: Opium Legalization and Opium Consumption in China. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2005.</ref> |

The Treaty of Nanking, the Supplementary Treaty of the Bogue, and two French and American agreements were all "unequal treaties" signed between 1842 and 1844. The terms of these treaties undermined China's traditional mechanisms of foreign relations and methods of controlled trade. Five ports were opened for trade, gunboats, and foreign residence: Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai. Hong Kong was seized by the British to become a free and open port. Tariffs were abolished thus preventing the Chinese from raising future duties to protect domestic industries and extraterritorial practices exempted Westerners from Chinese law. This made them subject to their own civil and criminal laws of their home country. Most importantly, the opium problem was never addressed and after the treaty was signed opium addiction doubled. China was forced to pay 21 million silver [[tael]]s as an indemnity, which was used to pay compensation for the traders' opium destroyed by Commissioner Lin. A couple of years after the treaties were signed internal rebellion began to threaten foreign trade. Due to the Qing government's inability to control collection of taxes on imported goods, the British government convinced the Manchu court to allow Westerners to partake in government official affairs. By the 1850s the [[Chinese Maritime Customs Service]], one of the most important bureaucracies in the Manchu Government, was partially staffed and managed by Western Foreigners.<ref name="Sharpe"/> In 1858 opium was legalised, and would remain a problem<ref>Miron, Jeffrey A. and Feige, Chris. The Opium Wars: Opium Legalization and Opium Consumption in China. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2005.</ref> |

||

Commissioner Lin, often referred to as "Lin the Clear Sky" for his moral probity,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.britannica.com/oscar/print?articleId=48330&fullArticle=true&tocId=4212|title=Lin Zexu|work=Encyclopædia Britannica|accessdate=3 June 2016}}</ref> was made a scapegoat. He was blamed for ultimately failing to stem the tide of opium imports and usage as well as for provoking an unwinnable war through his rigidity and lack of understanding of the changing world.<ref>{{cite web|author=Lee Khoon Choy|url=http://www.eastasianstudies.com/eastasian/5921_01.htm|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20141006202706/http://www.eastasianstudies.com/eastasian/5921_01.htm|title=Pioneers of Modern China: Understanding the Inscrutable Chinese: Chapter 1: Fujian Rén & Lin Ze Xu: The Fuzhou Hero Who Destroyed Opium |work=East Asian Studies|date=2007|accessdate=3 June 2016|archivedate=6 October 2014}}</ref> Nevertheless, as the Chinese nation formed in the 20th century, Lin became viewed as a hero, and has been immortalized at various locations around China.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lonelyplanet.com/worldguide/china/beijing/sights/1000228991|title=Monument to the People's Heroes|work=Lonely Planet|accessdate=3 June 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.chinaculture.org/gb/en_museum/2003-09/24/content_30174.htm|title=Lin Zexu Memorial|work=chinaculture.org|accessdate=3 June 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.olamacauguide.com/lin-zexu-memorial-museum.html|title=Lin Zexu Memorial Museum Ola Macau Travel Guide|work=olamacauguide.com|accessdate=3 June 2016}}</ref> |

Commissioner Lin, often referred to as "Lin the Clear Sky" for his moral probity,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.britannica.com/oscar/print?articleId=48330&fullArticle=true&tocId=4212|title=Lin Zexu|work=Encyclopædia Britannica|accessdate=3 June 2016}}</ref> was made a scapegoat. He was blamed for ultimately failing to stem the tide of opium imports and usage as well as for provoking an unwinnable war through his rigidity and lack of understanding of the changing world.<ref>{{cite web|author=Lee Khoon Choy|url=http://www.eastasianstudies.com/eastasian/5921_01.htm|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20141006202706/http://www.eastasianstudies.com/eastasian/5921_01.htm|title=Pioneers of Modern China: Understanding the Inscrutable Chinese: Chapter 1: Fujian Rén & Lin Ze Xu: The Fuzhou Hero Who Destroyed Opium |work=East Asian Studies|date=2007|accessdate=3 June 2016|archivedate=6 October 2014}}</ref> Nevertheless, as the Chinese nation formed in the 20th century, Lin became viewed as a hero, and has been immortalized at various locations around China.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lonelyplanet.com/worldguide/china/beijing/sights/1000228991|title=Monument to the People's Heroes|work=Lonely Planet|accessdate=3 June 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.chinaculture.org/gb/en_museum/2003-09/24/content_30174.htm |title=Lin Zexu Memorial |work=chinaculture.org |accessdate=3 June 2016 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160613173704/http://www.chinaculture.org/gb/en_museum/2003-09/24/content_30174.htm |archivedate=13 June 2016 |df= }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.olamacauguide.com/lin-zexu-memorial-museum.html |title=Lin Zexu Memorial Museum Ola Macau Travel Guide |work=olamacauguide.com |accessdate=3 June 2016 }}{{dead link|date=June 2017 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> |

||

The First Opium War both reflected and contributed to a further weakening of the Chinese state's power and legitimacy.<ref>{{cite news|last=Schell|first=Orville|title=A Rising China Needs a New National Story|url=https://www.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324425204578599633633456090.html|accessdate=14 July 2013|newspaper=[[Wall Street Journal]]|date=12 July 2013|author2=John Delury}}</ref> Anti-Qing sentiment grew in the form of rebellions, such as the [[Taiping Rebellion]], a war lasting from 1850{{ndash}}64 in which at least 20 million Chinese died. The decline of the Qing dynasty was beginning to be felt by much of the Chinese population.<ref name=":0" /> |

The First Opium War both reflected and contributed to a further weakening of the Chinese state's power and legitimacy.<ref>{{cite news|last=Schell|first=Orville|title=A Rising China Needs a New National Story|url=https://www.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324425204578599633633456090.html|accessdate=14 July 2013|newspaper=[[Wall Street Journal]]|date=12 July 2013|author2=John Delury}}</ref> Anti-Qing sentiment grew in the form of rebellions, such as the [[Taiping Rebellion]], a war lasting from 1850{{ndash}}64 in which at least 20 million Chinese died. The decline of the Qing dynasty was beginning to be felt by much of the Chinese population.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

| Line 298: | Line 298: | ||

* John K. Derden, "The British Foreign Office and Policy Formation: The 1840's," ''Proceedings & Papers of the Georgia Association of Historians'' (1981) pp 64–79. |

* John K. Derden, "The British Foreign Office and Policy Formation: The 1840's," ''Proceedings & Papers of the Georgia Association of Historians'' (1981) pp 64–79. |

||

* Morse, Hosea Ballou (1910). ''[[iarchive:internationalrel00mors|The International Relations of the Chinese Empire]]''. Volume 1. New York: Paragon Book Gallery. |

* Morse, Hosea Ballou (1910). ''[[iarchive:internationalrel00mors|The International Relations of the Chinese Empire]]''. Volume 1. New York: Paragon Book Gallery. |

||

* Headrick, Daniel R. (1979). [http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/imperialism/articles/headrick.pdf "The Tools of Imperialism: Technology and the Expansion of European Colonial Empires in the Nineteenth Century"] (PDF). ''The Journal of Modern History''. '''51''' (2): 231–263. [[Digital object identifier|doi]]:[https://doi.org/10.1086%2F241899 10.1086/241899]. Retrieved June 19, 2011. |

* Headrick, Daniel R. (1979). [https://web.archive.org/web/20090109162541/http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/imperialism/articles/headrick.pdf "The Tools of Imperialism: Technology and the Expansion of European Colonial Empires in the Nineteenth Century"] (PDF). ''The Journal of Modern History''. '''51''' (2): 231–263. [[Digital object identifier|doi]]:[https://doi.org/10.1086%2F241899 10.1086/241899]. Retrieved June 19, 2011. |

||

* [https://books.google.com/books?id=J9Q1AAAAMAAJ B''ulletins and Other State Intelligence'']. Compiled and arranged from the official documents published in the London Gazette. London: F. Watts. 1841. |

* [https://books.google.com/books?id=J9Q1AAAAMAAJ B''ulletins and Other State Intelligence'']. Compiled and arranged from the official documents published in the London Gazette. London: F. Watts. 1841. |

||

* Granville G. Loch. [http://books.google.com/books/about/The_Closing_Events_of_the_Campaign_in_Ch.html?id=YFthgRTEcFgC The Closing Events of the Campaign in China: The Operations in the Yang-tze-kiang and] treaty [http://books.google.com/books/about/The_Closing_Events_of_the_Campaign_in_Ch.html?id=YFthgRTEcFgC of Nanking] . London. 1843 [ 2014-07-13 ] |

* Granville G. Loch. [http://books.google.com/books/about/The_Closing_Events_of_the_Campaign_in_Ch.html?id=YFthgRTEcFgC The Closing Events of the Campaign in China: The Operations in the Yang-tze-kiang and] treaty [http://books.google.com/books/about/The_Closing_Events_of_the_Campaign_in_Ch.html?id=YFthgRTEcFgC of Nanking] . London. 1843 [ 2014-07-13 ] |

||

Revision as of 06:40, 8 June 2017

| First Opium War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Opium Wars | |||||||||

The East India Company steamship Nemesis (right background) destroying Chinese war junks during the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

19,000+ troops:[2]

37 ships:[2]

| 200,000 (including Bannermen) | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

69 killed in battle[2] 451 wounded[2] Nearly 300 executed or died in captivity in Formosa | 18,000–20,000 killed and wounded2 (est.)[2] | ||||||||

|

1 Comprising 5 troop ships, 3 brigs, 2 steamers, 1 survey vessel, and 1 hospital ship. 2 Casualties include Manchu bannermen and their families who committed mass suicide at the Battle of Chapu and Battle of Chinkiang.[3][4] | |||||||||

The First Opium War (第一次鴉片戰爭, 1839–42), also known as the Opium War and the Anglo-Chinese War, was fought between the United Kingdom and the Qing dynasty over their conflicting viewpoints on diplomatic relations, trade, and the administration of justice for foreign nationals in China.[5]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the demand for Chinese goods (particularly silk, porcelain, and tea) in the European market created a trade imbalance because the market for Western goods in China was virtually non-existent, as China was largely self-sufficient and Europeans were not allowed access to China's interior. European silver flowed into China when the Canton System, instituted in the mid-18th century, confined the sea trade to Canton and to the Chinese merchants of the Thirteen Factories. The British East India Company had a matching monopoly of British trade. The British East India Company began to auction opium grown on its plantations in India to independent foreign traders in exchange for silver. The opium was then transported to the Chinese coast and sold to local middlemen who retailed the drug inside China. This reverse flow of silver and the increasing numbers of opium addicts alarmed Chinese officials.

In 1839, the Daoguang Emperor, rejecting proposals to legalise and tax opium, appointed viceroy Lin Zexu to solve the problem by abolishing the trade. Lin confiscated around 20,000 chests of opium (approximately 1210 tons or 2.66 million pounds) without offering compensation, blockaded trade, and confined foreign merchants to their quarters.[6] The British government, although not officially denying China's right to control imports of the drug, objected to this unexpected seizure and used its naval and gunnery power to inflict a quick and decisive defeat,[5] a tactic later referred to as gunboat diplomacy.

In 1842, the Treaty of Nanking—the first of what the Chinese later called the unequal treaties—granted an indemnity and extraterritoriality to Britain, the opening of five treaty ports, and the cession of Hong Kong Island. The failure of the treaty to satisfy British goals of improved trade and diplomatic relations led to the Second Opium War (1856–60).[7] In China, the war is considered the beginning of modern Chinese history.[8]

Background

Establishment of trade

Direct maritime trade between Europe and China began in 1557 when the Portuguese leased an outpost at Macau. Other European nations soon followed the Portuguese lead, inserting themselves into the existing Asian maritime trade network to compete with Arab, Chinese, Indian, and Japanese traders in intra-regional trade.[9] After the Spanish conquest of the Philippines the exchange of goods between China and western Europe accelerated dramatically. From 1565 on, the Manila Galleons brought silver to the Asian trade network from mines in South America. China was the primary destination for these precious metals, as the imperial government mandated that Chinese goods could only be exported in exchange for silver bullion.[10]

British ships began to appear sporadically around the coasts of China from 1635 on; without establishing formal relations through the tributary system, British merchants were allowed to trade at the ports of Zhoushan and Xiamen in addition to Guangzhou (Canton).[11] Official British trade was conducted through the auspices of the British East India Company, which held a royal charter for trade with the Far East. The East India Company gradually came to dominate Sino-European trade from its position in India and due to the strength of the Royal Navy.[12]

Trade benefited after the newly-risen Qing dynasty relaxed maritime trade restrictions in the 1680s. Taiwan came under Qing control in 1683 and rhetoric regarding the "tributary status" of Europeans was muted.[11] Guangzhou (known as Canton in Europe) was the port of preference for incoming foreign trade. Ships did try to call at other ports, but these locations could not match the benefits of Guangzhou's geographic position at the mouth of the Pearl River trade network, nor did they have Guangzhou's long experience in balancing the demands of Beijing with those of Chinese and foreign merchants.[13] From 1700 onward Guangzhou dominated maritime trade with China, and this market process became known as the "Canton System".[13] From the systems' inception in 1757, trading in China was extremely lucrative for European and Chinese merchants alike as goods such as tea, porcelain, and silk were valued highly enough in Europe to justify expenses. However, foreign traders were only permitted to do business through a body of Chinese merchants known as the Cohong and were restricted to Canton. Foreigners could only live in one of the Thirteen Factories and were not allowed to enter or trade in any other part of China. These ordinances were collectively known as the Prevention Barbarian Ordinances (防范外夷規條.)[14]

Despite restrictions, silk and porcelain drove trade through their popularity in the west, and an insatiable demand for Chinese tea existed in Britain. These market forces resulted in a chronic trade deficit for European governments, who were forced to risk silver shortages in their domestic economies to supply the needs of their merchants in Asia (who still turned a profit by selling highly valuable Chinese goods to consumers in Europe.[14][15] From the mid-17th century onward around 28 million kilograms of silver were received by China, principally from European powers, in exchange for Chinese products.[16]

Trade philosophy and policy

Economic and social innovation led to a change in the parameters of Sino-European trade.[17] Arguments by Adam Smith and other economic theorists caused academic belief in mercantilism to decline in Britain.[18] During the Industrial Revolution Britain used its naval power to spread a broadly liberal economic model encompassing open markets and relatively barrier free international trade, a policy in line with the teachings of classical economics.[18] This stance on trade was intended to open foreign markets to the resources of Britain's colonies, as well as provide the British public with greater access to consumer goods.[18] Qing China followed a Confucian-Modernist economic philosophy that called for strict government intervention in industry for the sake of preserving societal stability. While the Qing state was not explicitly anti-trade, a perceived lack of need for imports (and the uncertainty they provided) limited pressure on the government to open further ports.[19] Qing China's rigid merchant hierarchy also blocked efforts to open ports to foreign ships and businesses. Chinese merchants in the interior wanted to avoid market fluctuations caused by importing foreign goods that would compete with domestic production, while the Hong houses of Canton profited greatly by keeping their city the only entry point for foreign products.[19][20]

Continued economic expansion in 17th and 18th century Europe increased the European demand for precious metals, raising prices and reducing the supply of bullion available for trade in China. The British adoption of the gold standard in 1821 resulted in the empire minting 40 million silver shillings among other coins, further reducing the availability of silver for trade in Asia.[17] The decline in supply sapped the ability of European merchants to purchase Chinese goods, which remained in high demand. Merchants were no longer able to sustain the China trade purely through profits made by selling Chinese goods in the west and were forced to take bullion out of circulation in Europe to buy goods in China.[9] This angered governments and fostered a great deal of animosity towards the Chinese.[21][15] Despite tensions, trade between China and Europe grew by an estimated 4% annually in the years leading up to the start of the opium trade.[22]

The Qing government was unaffected by fluctuation in silver prices, as China was able to import silver from Japan to stabilize it's money supply.[10] European goods remained in low demand in China, ensuring a trade surplus with European nations.[23]

At the turn of the 18th-century countries such as Britain, the Netherlands, Denmark, Russia, and the United States sought additional trading rights in China.[24] Foremost among the concerns of the western nations was the end of the Canton System and the opening of China's vast consumer markets to trade. Britain in particular was keen on reducing it's trade deficit, as the empire's implementation of the gold standard forced it to purchase silver from continental Europe and Mexico to supply domestic demand in addition to the British traders in China.[25] The perpetual expenditure of British bullion on Chinese products limited the amount of currency in British circulation, weakening the economy. Attempts by a British embassy (led by Macartney in 1793), a Dutch mission (under Van Braam in 1794), Russia's Golovkin in 1805 and the British again (Amherst in 1816) to negotiate increased access to the Chinese market were all vetoed by successive Qing Emperors.[15]

Opium trade expansion

In 1817, the British realised they could reduce the trade deficit (as well as turn the Indian colony profitable) by counter-trading in narcotic Indian opium.[21] The Qing administration initially tolerated opium importation because it created an indirect tax on Chinese subjects: increasing the silver supply of the foreign merchants through the sale of opium encouraged Europeans to spend more money on Chinese goods. This policy allowed the British to double tea exports from China to England, thereby profiting the Qing monopoly on tea exports held by the imperial treasury and its agents in Canton.[26]

The opium sold was produced in the traditionally cotton-growing regions of India under British East India Company monopoly (Bengal) and in the Princely states (Malwa) outside the company's control. Both areas had been hard hit by the introduction of factory-produced cotton cloth, which used cotton grown in Egypt or the American South. The opium was auctioned in Calcutta (now Kolkata) on the condition that it be shipped by British traders to China, where profits were guaranteed. Opium as a medicinal ingredient was documented in texts as early as the Tang dynasty but its recreational use was limited and there were laws against its abuse. Limited British sales of opium began in 1781, with exports to China increasing as the East India Company solidified it's control over India. East India Company ships brought their cargoes to islands off the coast, especially Lintin Island, where Chinese traders with fast and well-armed small boats took the goods for inland distribution, paying for them with silver. In the early 19th century American merchants joined the trade and began to introduce opium from Turkey into the Chinese market — this was of lesser quality but cheaper to produce, and the resulting competition among British and American merchants drove down the price of opium, leading to an increase in the availability of the drug for Chinese consumers.[23] The demand for opium increased so rapidly and was so profitable in the Chinese interior (which was inaccessibly to European merchants) that Chinese opium merchants (who could sell inland) began to seek out more suppliers for the drug. The resulting shortage drew more European merchants into the opium trade. From 1804 to 1820, a period when the Qing treasury needed to finance the suppression of rebellions, the flow of silver gradually reversed: Chinese merchants were now exporting it to pay for opium rather than Europeans paying for Chinese goods with the precious metal.[27] European ships were able to arrive in Canton with their holds filled with opium, sell their cargo, use the proceeds to buy Chinese goods, and turn a profit, often in the form of silver bullion.[10] This silver would be used to acquire further goods in China or be shipped back to Europe, where many governments were implementing coinage reforms.[14]

The Qing imperial court debated whether or how to end the opium trade, but its efforts were complicated by local officials (including the Governor-general of Canton) and the Hongs, who profited greatly from the bribes and taxes involved.[28] In 1810 the Daoguang Emperor issued an edict concerning the matter, declaring,

Opium has a harm. Opium is a poison, undermining our good customs and morality. Its use is prohibited by law. Now the commoner, Yang, dares to bring it into the Forbidden City. Indeed, he flouts the law! However, recently the purchasers, eaters, and consumers of opium have become numerous. Deceitful merchants buy and sell it to gain profit. The customs house at the Ch'ung-wen Gate was originally set up to supervise the collection of imports (it had no responsibility with regard to opium smuggling). If we confine our search for opium to the seaports, we fear the search will not be sufficiently thorough. We should also order the general commandant of the police and police- censors at the five gates to prohibit opium and to search for it at all gates. If they capture any violators, they should immediately punish them and should destroy the opium at once. As to Kwangtung [Guangdong] and Fukien [Fujian], the provinces from which opium comes, we order their viceroys, governors, and superintendents of the maritime customs to conduct a thorough search for opium, and cut off its supply. They should in no ways consider this order a dead letter and allow opium to be smuggled out![29]

A turning point came in 1834: reformers in England who advocated free trade had succeeded in ending the monopoly of the British East India Company under the Charter Act of the previous year, finally opening British trade to private entrepreneurs, many of whom joined the lucrative opium trade.[30]

Napier Affair

In late 1834, to accommodate the revocation of the East India Company's monopoly, the British sent Lord William John Napier to Macau along with John Francis Davis and Sir George Best Robinson, 2nd Baronet as British Superintendents of Trade in China. Napier was instructed to obey Chinese regulations, communicate directly with Chinese authorities, superintend trade pertaining to the contraband trade of opium, and to survey China's coastline. Napier tried to circumvent the restrictive Canton System that forbade direct contact with Chinese officials by attempting to send a letter directly to the Viceroy of Canton. The Viceroy refused to accept it, and on 2 September of that year an edict was issued which closed trade. Other nationalities, such as the Americans, prospered through their continued peaceful trade with China but the British were all told to leave Canton for either Whampoa or Macau.[31] Lord Napier had to return to Macau (where he died a few days later)[32] After Lord Napier's death, Captain Charles Elliot received the King Commission in 1836 to continue Napier's work of conciliating the Chinese.[32]

Destruction of opium at Humen

By 1838, the British were selling roughly 1,400 tons of opium per year to China. Legalisation of the opium trade was the subject of ongoing debate within the Chinese administration, but it was repeatedly rejected, and as of 1838 the government sentenced native drug traffickers to death.

In 1839, the Daoguang Emperor appointed scholar-official Lin Zexu to the post of Special Imperial Commissioner, with the task of eradicating the opium trade.[33] Lin sent an open letter to Queen Victoria questioning the moral reasoning of the British government. Citing what he understood to be a strict prohibition of the trade within Great Britain, Lin questioned how it could then profit from the drug in China. He wrote: "Your Majesty has not before been thus officially notified, and you may plead ignorance of the severity of our laws, but I now give my assurance that we mean to cut this harmful drug forever."[34] The letter never reached the Queen, with one source suggesting that it was lost in transit.[35] Lin pledged that nothing would divert him from his mission, "If the traffic in opium were not stopped a few decades from now we shall not only be without soldiers to resist the enemy, but also in want of silver to provide an army."[36] Lin banned the sale of opium and demanded that all supplies of the drug be surrendered to the Chinese authorities. He also closed the Pearl River Channel, effectively holding British traders hostage in Canton.[23] As well as seizing opium supplies in the factories, Chinese troops boarded British ships in international waters outside Chinese jurisdiction, where their cargo was still legal, and destroyed the opium aboard.[37]

The British Superintendent of Trade in China, Charles Elliot, at first protested the decision and ordered the opium ships to flee and prepare for battle. Lin then quarantined the foreign dealers in their warehouses and kept them from communicating with their ships in port.[36] To defuse the situation, Elliot convinced the British traders to cooperate with Chinese authorities and hand over their opium stockpiles, with the promise of eventual compensation for their loss by the British government.[23] While this amounted to a tacit acknowledgment that the British government did not disapprove of the trade, it also placed a huge liability on the exchequer. This promise, and the inability of the British government to pay it without causing a political storm, was an important casus belli for the subsequent British offensive.[38]

During April and May 1839, British and American dealers surrendered 20,283 chests and 200 sacks of opium which was publicly destroyed on the beach outside of Guangzhou. Lin was able to sustain the prohibition policy for many months.[36]

After the opium was surrendered, trade was restarted on the strict condition that no more opium would be shipped into China. Lin demanded that all merchants sign a bond promising not to deal in opium, under penalty of death.[39] The British officially opposed signing of the bond, but some merchants who did not trade opium, such as Olyphant & Co. and Augustine Heard & Co. were willing to sign.[40]

War

In late October a merchant ship, the Thomas Coutts, arrived in China and sailed to Canton. This ship was owned by Quakers who refused on religious grounds to deal in opium, a fact known to the Chinese authorities. The ship's captain, Warner, believed Elliot had exceeded his legal authority by banning the signing of the "no opium trade" bond,[41] and negotiated with the governor of Canton. Warner hoped that all British ships could negotiate to unload their goods at Chuenpi, an island near Humen.[42]

To prevent other British ships from following the Thomas Coutts, Elliot ordered a blockade of the Pearl River. Fighting began on 3 November 1839, when a second British ship, the Royal Saxon, attempted to sail to Canton. The British Royal Navy ships HMS Volage and HMS Hyacinth fired warning shots at the Royal Saxon. In response to this commotion, a fleet of Chinese war junks under the command of Guan Tianpei sailed out to protect the Royal Saxon.[43] The ensuing First Battle of Chuenpi resulted in the destruction of 4 Chinese War Junks and the withdraw of both fleets.[44]

The Qing navy's official report claimed that the navy attempted to protect the British merchant vessel and reported a great victory for that day. In reality, they had been out-classed by the Royal Naval vessels and many Chinese ships were disabled.[44] Elliot reported that his squadron was protecting the 29 British ships in Chuenpi. Elliot knew that the Chinese would reject any contacts with the British and would eventually attack with fire rafts. Elliot ordered all ships to leave Chuenpi and head for Tung Lo Wan, 20 miles (30 km) from Macau. Elliot asked Adrião Acácio da Silveira Pinto, the Portuguese governor of Macau, to let British ships load and unload their goods there in exchange for paying rent and any duties. The governor refused for fear that the Chinese would discontinue supplying food and other necessities to Macau, for on 14 January 1840 the Emperor had asked all foreigners to halt material assistance to the British.[44][45]

Left without a major base of operations in China, the British withdrew their merchant shipping from the region while maintaining the Royal Navy's china squadron. Plans were made by the British to regroup and launch a series of attacks on Chinese ports. Foreign Secretary Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, a politician known for his aggressive foreign policy and advocacy for free trade, was in favor of the war with the Qing Empire. From London, Lord Palmerston took command of operations in China, ordering the East India Company to divert troops from India in preparation for a limited war against the Chinese. Superintendent Elliot remained in command of the Royal Navy's warships, Commodore James Bremer led the Royal Marines, and Major General Hugh Gough commanded the British land forces, in addition to serving as the overall commander of British forces in China.[46] The cost of the war would be paid by the British Government.[44][47][48][49]

The Qing Chinese were commanded by Qishan (ᡴᡳᡧᠠᠨ), who replaced Lin Zexu in 1840 as the Viceroy of Liangguang.[50] The Chinese Navy was commanded by Guan Tianpei, who had fought the British at Chuenpi. The Qing southern army and garrisons were commanded by General Yang Fang. Overall command was invested in the Daoguang Emperor and his court.[8] The Chinese government initially believed that, as in the 1834 Nappier Affair, the British had been successfully expelled.[47] Few preparations were made for a British attack in southern China, and the events leading to the eventual outbreak of the Sino-Sikh War in 1841 were seen as a greater cause for concern.[51]

Offensive operations begin

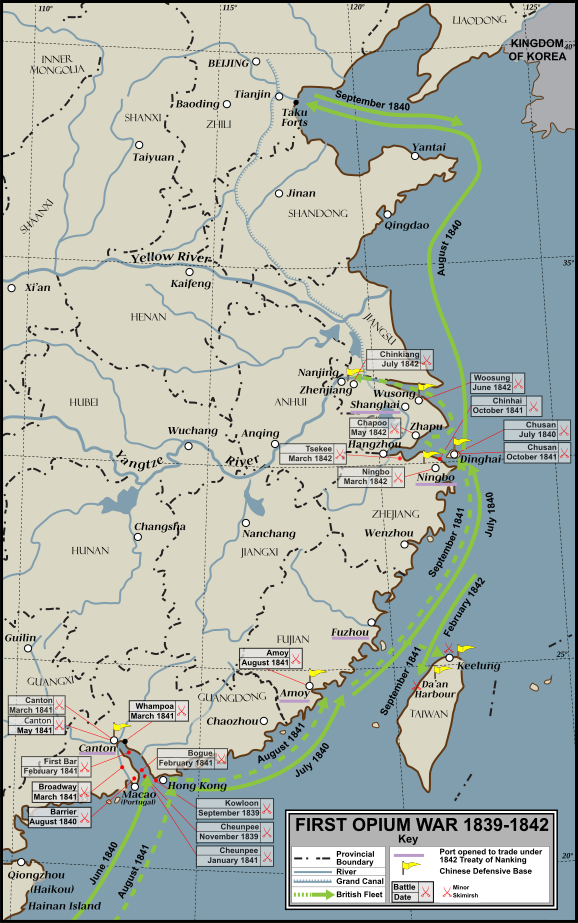

In June 1840, an expeditionary force of British troops aboard 15 barracks ships, four steam-powered gunboats and 25 smaller boats reached the mouth of the Pearl River from Singapore.[52] The marines were headed by Commodore Bremer. The British issued an ultimatum demanding the Qing Government pay compensation for losses suffered from interrupted trade and the destruction of opium.[53]

Palmerston instructed the joint plenipotentiaries Elliot and his cousin Admiral George Elliot to acquire the cession of at least one island for trade on the Chinese coast.[54] With the British expeditionary force now in place, a combined naval and ground assault was launched on the Chusan Archipelago. Zhoushan Island, the largest and best defended of the islands was the primary target, as was it's vital port of Chusan. The city was captured on 5 July after the Chinese defenders withdrew.[53] The British occupied the harbour in preparation for use as a staging point for operations on the Pearl River. Five months later the Royal Navy sailed up the river to Humen (known to the British as Bogue) and began to bombard the Qing defences there. On 7 January 1841 the British won a decisive victory in the Second Battle of Chuenpi, destroying 11 Junks of the Chinese fleet and capturing the majority of the Humen forts.[55]

Knowing the strategic value of Pearl River Delta to China and aware that British naval superiority made a recapture of the region unlikely, Qishan attempted to prevent the war for widening further.[56] On 21 January Qishan and Elliot drafted the Convention of Chuenpi, a document which they hoped would end the war.[56][57] The convention would establish equal diplomatic rights between Britain and China, exchange Hong Kong Island for Chusan, and reopen trade in Canton by 1 February 1841.[57] China would also pay six millions of silver dollars as recompense for the opium destroyed at Humen in 1838. The status of the opium trade was left open to be discussed at a future date. Despite the successful negotiations between Qishan and Elliot, both of their respective governments refused to sign the convention. The Daoguang Emperor was infuriated that Qing territory would be given up in a treaty that had been signed without his permission, and ordered Qishan arrested (later sentenced to death, then commuted to military service.) Lord Palmerston recalled Elliot and refused to sign the convention, wanting more concessions to be forced from the Chinese.[45][50]

The brief interlude in the fighting ended in the beginning of February after the Chinese refused to reopen Canton to British trade. On 19 February HMS Nemesis came under fire from a fort on North Wangtong Island, prompting a British response.[58] Elliot's replacement in China, Henry Pottinger, ordered a blockade of the Pearl River and resumed combat operations against the Chinese. The British captured the remaining Bogue forts on 26 February during the Battle of the Bogue and the Battle of First Bar on the following day.[59][56] With the Pearl River cleared of Chinese defenses, the British attacked Canton, taking the Thirteen Factories with very few casualties.[56] The city was partially occupied by the British on 18 March, and trade was reopened. After several days of further military successes, British forces commanded the high ground around Canton. Yishan (Qishan's replacement and the Daoguang Emperor's cousin) and Yang Fang launched a nighttime raid on the British army on 23 May.[55] This attack failed in the face of superior British firepower, and set off a series of battles in the Canton area known as the Battle of Canton.[56] The Qing army was severely weakened by infighting between units and lack of confidence in Yishan, who openly distrusted Cantonese soldiers and instead relied on forces drawn from Fujian.[60] The British counter-attacked on 25 May, taking the last four Qing forts in Canton and bombarding the city.[55] On 29 May a crowd of Cantonese villagers and townspeople attacked and drove off a company of 60 Indian sepoys in what became known as the Sanyuanli Incident. The fighting subsided on 30 May 1841 and Canton came fully under British occupation.[61][62][56]

In March 1841 the Broadway expedition captured a number of Chinese forts on the Xi River by bombarding the positions until the defenders fled, then landing marines ashore.[63] That same month the British destoyed a Qing fort near Pazhou and captured Whamoa.[64][64]

On 26 August the British assaulted and took a series of forts in the Battle of Amoy. 26 Chinese junks and 128 cannon were captured after the majority of the garrison withdrew. The city of Amoy fell on 27 August.[65][63]

Changes in the British parliament resulted in Lord Palmerston being removed from the post of Foreign Minister on 30 August. William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne replaced him, and sought a more measured approach to the situation in China. He remained a supporter of the war.[66][67]

In September 1841, the British transport ship Nerbudda was shipwrecked off the northern coast of Taiwan, followed by the brig Ann in March 1842. The survivors were marched to southern Taiwan, where they were imprisoned. 197 were executed on 10 August 1842. An additional 87 died from ill-treatment in captivity. This became known as the Nerbudda incident.[68]

October 1841 saw the British solidify their control over the Pearl River. Chusan had been exchanged for Hong Kong on the authority of Qishan in January 1841, after which the city had been re-garrisoned by the Qing. The British captured Chusan for a second time on 1 October.[69]

On 10 October a British naval force bombarded and captured a fort on the outskirts of Ningbo in central China. The Chinese authorities evacuated the populace, and the empty city was taken by the British on 13 October.[70][71]

Fighting ceased for the winter of 1841 while the British resupplied and dealt with a cholera outbreak in Canton.[72] Misinformation sent by Yishan to the Emperor in Beijing resulted in the continued British threat being downplayed, while individual provincial leaders fortified against further naval incursions.[60][14]

The Daoguang Emperor ordered his cousin Yijing to retake the city of Ningpo in the spring. In the ensuing Battle of Ningpo on 10 March, the British garrison repelled the assault with rifle fire and naval artillery.[73][74] The British pursed the retreating Chinese army, capturing the nearby city of Cixi on 15 March.[75]

Zhapu was captured on 18 May following the Battle of Chapu.[3] A British fleet bombarded the town, forcing it's surrender. A holdout of 300 soldiers of the Eight Banners stalled the advance of British army for several hours, an act that was commended by General Gough.[76][77]

Yangtze river campaign

With many Chinese ports now blocked or under British occupation, Gough sought to cripple the finances of the Qing Empire by striking up the Yangtze River. 25 Warships and 10,000 men were assembled in Ningpo and at Zhapu in May for a planned advance into the interior.[78] They sailed up the Yangtze and captured the emperor's tax barges, a devastating blow that slashed the revenue of the imperial court in Beijing to just a fraction of what it had been.[79]

On 14 June the mouth of the Huangpu River was captured by the British fleet. On 16 June the Battle of Woosung occurred, after which the British captured the towns of Wusong and Baoshan. The undefended outskirts of Shanghai were occupied by the British on 19 June.[80][81][78]

The fall of Shanghai left the vital city of Nanjing (Known as Jiangning under the Qing) vulnerable. The Qing had amassed an army of 56,000 Manchu Bannermen and Han Green Standards to defend Liangjiang Province, and had strengthened their river defences on the Yangtze. However, by May 1842 British naval activity in Northern China had led to resources and manpower being withdrawn to defend Beijing.[82] The Qing commander in Liangjiang Province released 16 British prisoners with the hope that a ceasefire could be reached, but poor communications led both the Qing government and the British to reject any overtures at peace.[83] In secret, the Daoguang Emperor did consider signing a peace treaty with the British, but only in regards to the Yangtze River and not the war as a whole. Had it been signed, Britain would have be paid to not enter the Yangtze.[84]

On 14 July the British fleet on the Yangtze began to sail up the river. Reconnaissance had alerted Gough to the logistical importance of the city of Zhenjiang, and plans were made to capture it.[85] Most of the city's guns had been relocated to Wusong and had been captured by the British when said city had been taken. The Qing commanders inside the city were disorganised, with Chinese sources stating that over 100 traitors were executed in Zhenjiang before the battle.[86] The British fleet arrived off of the city on the morning of 21 July. The Chinese initially retreated from the city into the surrounding hills, causing a premature British landing. Fighting soon erupted, beginning the Battle of Chinkiang. British soldiers blew open the western gate and stormed into the city, where fierce street to street fighting ensued. Zhenjiang was devastated by the battle, with many Chinese soldiers and their families committed suicide rather than be taken prisoner.[3][51] The British suffered their highest combat losses of the war taking the city.[81][31][77]

After capturing Zhenjiang the British fleet cut the vital Grand Canal, paralyzing the Caoyun system and severely disrupting the Chinese ability to distribute grain throughout the Empire.[87][81]

The British departed Zhenjiang on 3 August, intending to sail on to Nanjing. They arrived outside the Jiangning District on 9 August, and were in position to assault the city by the 11th. On the 14th a delegation from Nanjin (Nanking) met with the British, and on the 21st the Daoguang Emperor authorized his diplomats to sign a peace treaty with the British.[88][89][90]

The First Opium war finally ended on 29 August 1842 with the signing of the Treaty of Nanking.[91] The document was signed by officials of the British and Qing empires aboard the HMS Cornwallis.[92]

Technology and tactics

British

The British military superiority during the conflict drew heavily on the success of the Royal Navy.[93] British warships carried more guns than their Chinese opponents and had raised decks that were all but impossible for the Chinese junks to board. Steam ships such as the HMS Nemesis were able to move against winds and tides in Chinese rivers, and were armed with heavy guns and congreve rockets.[93] Several of the larger British warships in China (notably HMS Cornwallis, HMS Wellesley, and HMS Melville) carried more guns than entire fleets of Chinese junks.[78] British naval superiority allowed the Royal Navy to attack Chinese forts at will with very little danger to themselves, as British naval cannons out-ranged the vast majority of the Qing artillery.[78][94]

British soldiers in China were equipped with Brunswick rifles and rifle-modified Brown Bess muskets, both of which possessed an effective firing range of 200–300 metres.[95] British marines were equipped with percussion caps that greatly reduced weapon misfires and allowed firearms to be used in damp environments. In terms of gunpowder, the British formula was better manufactured and contained more sulfur than the Chinese mixture.[95] This granted British weapons an advantage in terms of range, accuracy and projectile velocity. British horse artillery was lighter (owing to improved forging methods) and more maneuverable than the cannons used by the Chinese. As with the naval artillery, British guns out-ranged the Chinese cannon.[94]

In terms of tactics, the British forces in China followed doctrines established during the Napoleonic Wars that were adapted during the various colonial wars of the 1820s and 1830s. Many of the British soldiers deployed to China were veterans of colonial wars in India and had experience fighting larger but technologically inferior armies. In battle, the British line infantry would advance towards the enemy in columns, forming ranks once they had closed to firing range. Companies would commence firing volleys into the enemy ranks until they retreated. If a position needed to be taken, an advance or charge with bayonets would be ordered. Light infantry companies screened the line infantry formations, protecting their flanks and utilizing skirmishing tactics to disrupt the enemy.[72] British artillery was used to destroy the Qing artillery and break up enemy formations. During the conflict, the British superiority in range, rate of fire, and accuracy allowed the infantry to deal significant damage to their enemy before the Chinese could return fire.[96] The use of naval artillery to support infantry operations allowed the British to take cities and forts will minimal casualties.[97][98]

The overall strategy of the British during the war was to inhibit the finances of the Qing Empire. This was accomplished through the capture of Chinese cities and by blockading major river systems.[99] Once a fort or city was captured, the British destroyed the local arsenal and disabled all of the captured guns.[98] They would then move on to the next target, leaving a small garrison behind. This strategy was planned and implemented by Major General Gough, who was able to operate with minimal input from the British government after Superintendent Elliot was recalled in January 1841.[100] The large number of private British merchants and East India Company ships deployed in Singapore and the India colonies ensured that the British forces in China were well supplied.[101][6]

Qing

From the onset of the war the Chinese navy was severely disadvantaged. Chinese war junks were intended for use against pirates or equivalent types of vessels, and were most effective in close range river engagements. Due to their slow speed, Qing captains consistently found themselves sailing towards much more maneuverable British ships, and as a consequence could only use their bow guns.[102] The size of the British ships made traditional boarding tactics useless, and the junks carried smaller numbers of inferior guns.[73] In addition, the Chinese ships were poorly armored; in several battles, British shells and rockets penetrated Chinese magazines and detonated the junk's gunpowder stores. Highly maneuverable steamships such the HMS Nemesis could decimate small fleets of junks.[78] The only western-style warship in the Qing Navy, the converted East Indiaman Cambridge, was destroyed in the Battle of First Bar.[103]

The nature of the conflict resulted in the Chinese relying heavily an extensive network of defensive fortifications. The Kangxi Emperor (1654 – 1722) began the construction of river defences to combat pirates, and encouraged the use of western-style cannons. By the time of the First Opium War multiple forts defended most major Chinese cities. Although the forts were well armed and strategically positioned, the Qing defeat exposed major flaws in their design. Chinese cannon were crafted using sub-par forging methods, limiting their effectiveness. The Chinese blend of gunpowder contained more charcoal than the British mixture did.[95] While this made the explosive more stable and thus easier to store, it also limited its potential as a propellant, decreasing projectile range and accuracy.[95] Chinese forts were unable to withstand attacks by European weaponry, as they were designed without angled glacis and many did not have protected magazines. The limited range of the Qing cannon allowed the British to bombard the Qing defences from a safe distance, then land soldiers to storm them with minimal risk. The Chinese underestimated the ability of the British to force their way up major rivers, and Qing logistics suffered as a result.[99]

At the start of the war the Qing consisted of over 200,000 men. These forces consisted of Manchu Bannermen, the Green Standard Army, provincial militias, and imperial garrisons. The Qing armies were armed with matchlocks and shotguns, which had an effective range of 100 metres.[95] Chinese historians estimated 30–40% of the Qing forces were armed with firearms.[104] Chinese soldiers were also equipped with halberds, spears, swords, and crossbows. The Qing dynasty also employed large batteries of artillery in battle.[105]

The tactics of the Qing remained consistent with what they had been in previous centuries.[104][106] Soldiers with firearms would form ranks and fire volleys into the enemy while men armed with spears and pikes would drive the enemy off of the battlefield.[107] Cavalry was used to break infantry formations and pursue routed enemies.[108] Qing artillery was used to scatter enemy formations. During the First Opium War the Qing forces were unable to successfully deal with British firepower. Chinese melee formations were decimated by artillery, and Chinese soldiers armed with matchlocks could not effectively exchange fire with British ranks, who greatly out ranged them.[72] Most battles of the war were fought in cities or on cliffs and riverbanks, limiting the Qing usage of cavalry. Many Qing cannon were destroyed by British counter-battery fire, and the British light infantry was constantly able to flank and capture the Chinese artillery batteries.[105] A British officer said of the opposing Qing forces, "The Chinese are robust muscular fellows, and no cowards; the Tartars [i.e. Manchus] desperate; but neither are well commanded nor acquainted with European warfare. Having had, however, experience of three of them, I am inclined to supposed that a Tartar bullet is not a whit softer than a French one."[105]

The strategy of the Qing Dynasty during the war was to prevent the British from seizing Chinese territory.[105] This defensive strategy was hampered by the Qing severely underestimating the capacity of the British military. Qing defenses on the Pearl and Yangtze rivers were ineffective in stopping the British push inland, and superior naval artillery prevented the Chinese from retaking cities.[74][23]

Aftermath

The war ended in the signing of China's first Unequal Treaty, the Treaty of Nanking.[91][92] In the supplementary Treaty of the Bogue, the Qing empire also recognised Britain as an equal to China and gave British subjects extraterritorial privileges in treaty ports. In 1844, the United States and France concluded similar treaties with China, the Treaty of Wanghia and Treaty of Whampoa, respectively.

Some historians claim that Lord Palmerston, the British Foreign Secretary, initiated the Opium War to maintain the principle of free trade.[109] Professor Glenn Melancon, for example, argues that the issue in going to war was not opium but Britain's need to uphold its reputation, its honour, and its commitment to global free trade. China was pressing Britain just when the British faced serious pressures in the Near East, on the Indian frontier, and in Latin America. In the end, says Melancon, the government's need to maintain its honour in Britain and prestige abroad forced the decision to go to war.[45] Former American president John Quincy Adams commented that opium was "a mere incident to the dispute ... the cause of the war is the kowtow—the arrogant and insupportable pretensions of China that she will hold commercial intercourse with the rest of mankind not upon terms of equal reciprocity, but upon the insulting and degrading forms of the relations between lord and vassal."[110]

Critics, however, focused on the immorality of opium. William Ewart Gladstone denounced the war as "unjust and iniquitous" and criticised Lord Palmerston's willingness "to protect an infamous contraband traffic."[47] The public and press in the United States and Britain expressed outrage that Britain was supporting the opium trade. Lord Palmerston justified military action by saying that no one could "say that he honestly believed the motive of the Chinese Government to have been the promotion of moral habits" and that the war was being fought to stem China's balance of payments deficit.[111]

Legacy

The war marked the start of what 20th century nationalists called the "Century of Humiliation". The ease with which the British forces defeated the numerically superior Chinese armies damaged the Qing dynasty's prestige. The Treaty of Nanking was a step to opening the lucrative Chinese market to global commerce and the opium trade. The interpretation of the war, which was long the standard in the People's Republic of China, was summarized in 1976: The Opium War, "in which the Chinese people fought against British aggression, marked the beginning of modern Chinese history and the start of the Chinese people's bourgeois-democratic revolution against imperialism and feudalism."[8]

The Treaty of Nanking, the Supplementary Treaty of the Bogue, and two French and American agreements were all "unequal treaties" signed between 1842 and 1844. The terms of these treaties undermined China's traditional mechanisms of foreign relations and methods of controlled trade. Five ports were opened for trade, gunboats, and foreign residence: Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai. Hong Kong was seized by the British to become a free and open port. Tariffs were abolished thus preventing the Chinese from raising future duties to protect domestic industries and extraterritorial practices exempted Westerners from Chinese law. This made them subject to their own civil and criminal laws of their home country. Most importantly, the opium problem was never addressed and after the treaty was signed opium addiction doubled. China was forced to pay 21 million silver taels as an indemnity, which was used to pay compensation for the traders' opium destroyed by Commissioner Lin. A couple of years after the treaties were signed internal rebellion began to threaten foreign trade. Due to the Qing government's inability to control collection of taxes on imported goods, the British government convinced the Manchu court to allow Westerners to partake in government official affairs. By the 1850s the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, one of the most important bureaucracies in the Manchu Government, was partially staffed and managed by Western Foreigners.[36] In 1858 opium was legalised, and would remain a problem[112]

Commissioner Lin, often referred to as "Lin the Clear Sky" for his moral probity,[113] was made a scapegoat. He was blamed for ultimately failing to stem the tide of opium imports and usage as well as for provoking an unwinnable war through his rigidity and lack of understanding of the changing world.[114] Nevertheless, as the Chinese nation formed in the 20th century, Lin became viewed as a hero, and has been immortalized at various locations around China.[115][116][117]

The First Opium War both reflected and contributed to a further weakening of the Chinese state's power and legitimacy.[118] Anti-Qing sentiment grew in the form of rebellions, such as the Taiping Rebellion, a war lasting from 1850–64 in which at least 20 million Chinese died. The decline of the Qing dynasty was beginning to be felt by much of the Chinese population.[10]

The opium trade faced intense enmity from the later British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone.[119] As a member of Parliament, Gladstone called it "most infamous and atrocious" referring to the opium trade between China and British India in particular.[120] Gladstone was fiercely against both of the Opium Wars Britain waged in China in the First Opium War initiated in 1840 and the Second Opium War initiated in 1857, denounced British violence against Chinese, and was ardently opposed to the British trade in opium to China.[121] Gladstone lambasted it as "Palmerston's Opium War" and said that he felt "in dread of the judgments of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China" in May 1840.[122] A famous speech was made by Gladstone in Parliament against the First Opium War.[123][124] Gladstone criticised it as "a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to cover this country with permanent disgrace".[125] His hostility to opium stemmed from the effects opium brought upon his sister Helen.[126] Due to the First Opium war brought on by Palmerston, there was initial reluctance to join the government of Peel on part of Gladstone before 1841.[127]

Interactive map

See also

Individuals:

Contemporaneous Qing Dynasty wars:

- Sino-Sikh war (1841–1842)

Fictional and narrative literature

- Leasor, James. Mandarin-Gold. London: Heinemann, 1973, e-published James Leasor Ltd, 2011

- Amitav Ghosh, River of Smoke (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2011).

- Timothy Mo, An Insular Possession (Chatto and Windus, 1986; Paddleless Press, 2002)

Notes

- ^ Le Pichon, Alain (2006). China Trade and Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-19-726337-2.

- ^ a b c d e Martin, Robert Montgomery (1847). China: Political, Commercial, and Social; In an Official Report to Her Majesty's Government. Volume 2. London: James Madden. pp. 80–82.

- ^ a b c Rait, Robert S. (1903). The Life and Campaigns of Hugh, First Viscount Gough, Field-Marshal. Volume 1. p. 265.

- ^ John Makeham (2008). China: The World's Oldest Living Civilization Revealed. Thames & Hudson. p. 331. ISBN 978-0-500-25142-3.

- ^ a b Tsang, Steve (2007). A Modern History of Hong Kong. I.B.Tauris. p. 3–13, 29. ISBN 1-84511-419-1.

- ^ a b Farooqui, Amar (March 2005). Smuggling as Subversion: Colonialism, Indian Merchants, and the Politics of Opium, 1790–1843. Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0886-7.

- ^ Tsang 2004, p. 29

- ^ a b c The History of Modern China (Beijing, 1976) quoted in Janin, Hunt (1999). The India–China Opium Trade in the Nineteenth Century. McFarland. p. 207. ISBN 0-7864-0715-8.

- ^ a b Gray 2002, p. 22–23.

- ^ a b c d Goldstone, Jack A. (19 December 2016). Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World: Population Change and State Breakdown in England, France, Turkey, and China,1600–1850; 25th Anniversary Edition. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-40860-6.

- ^ a b Spence 1999, p. 120.

- ^ Bernstein, William J. (2008). A splendid exchange: how trade shaped the world. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-87113-979-5.

- ^ a b Van Dyke, Paul A. (2005). The Canton trade: life and enterprise on the China coast, 1700–1845. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. pp. 6–9. ISBN 962-209-749-9.

- ^ a b c d Alain Peyrefitte, The Immobile Empire—The first great collision of East and West—the astonishing history of Britain's grand, ill-fated expedition to open China to Western Trade, 1792–94 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), p. 520–545

- ^ a b c Peyrefitte 1993, p 487–503

- ^ Early American Trade, BBC

- ^ a b Report from the Select Committee on the Royal Mint: together with the minutes of evidence, appendix and index, Volume 2 (Great Britain. Committee on Royal Mint, 1849), p. 172.

- ^ a b c L.Seabrooke (2006). "Global Standards of Market Civilization". p. 192. Taylor & Francis 2006

- ^ a b "Grandeur of the Qing Economy". www.learn.columbia.edu. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ Compilation Group for the "History of Modern China" Series. (2000). p. 17.

- ^ a b Hanes III, W. Travis; Sanello, Frank (2002). The Opium Wars. Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks, Inc. p. 20.

- ^ Meyers, Wang (2003) pp. 587

- ^ a b c d e "China: The First Opium War". John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York. Retrieved 2 December 2010Quoting British Parliamentary Papers, 1840, XXXVI (223), p. 374

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Downs. pp. 22–24

- ^ Liu, Henry C. K. (4 September 2008). Developing China with sovereign credit. Asia Times Online.

- ^ Peyrefitte, 1993 p520

- ^ Layton 1997, p. 28.

- ^ Peter Ward Fay, The Opium War, 1840–1842: Barbarians in the Celestial Empire in the Early Part of the Nineteenth Century and the Way by Which They Forced the Gates Ajar (Chapel Hill, North Carolina:: University of North Carolina Press, 1975).

- ^ Fu, Lo-shu (1966). A Documentary Chronicle of Sino-Western relations, Volume 1. p. 380.

- ^ "China: The First Opium War". John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York. Retrieved 2 December 2010Quoting British Parliamentary Papers, 1840, XXXVI (223), p. 374

- ^ a b Michie, Alexander (28 August 2012). The Englishman in China During the Victorian Era: As Illustrated in the Career of Sir Rutherford Alcock Volume 1 (Vol. 1 ed.). HardPress Publishing. ISBN 978-1-290-63687-2.

- ^ a b "The Napier Affair (1834)". Modern China Research. Institute of Modern History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ "England and China: The Opium Wars, 1839–60". victorianweb.org. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ Commissioner Lin: Letter to Queen Victoria, 1839. Modern History Sourcebook.

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2004, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d Kort, June M. Grasso, Jay Corrin, Michael (2009). Modernization and revolution in China : from the opium wars to the Olympics (4. ed.). Armonk, N.Y.: Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-2391-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Evans, Richard J. (1 September 2016). The Pursuit of Power: Europe, 1815–1914. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-241-29577-9.

- ^ "Foreign Mud: The opium imbroglio at Canton in the 1830s and the Anglo-Chinese War," by Maurice Collis, W. W. Norton, New York, 1946

- ^ Coleman, Anthony (1999). Millennium. Transworld Publishers. pp. 243–244. ISBN 0-593-04478-9.

- ^ "Doing Business with China: Early American Trading Houses". www.library.hbs.edu. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2004, p. 68.

- ^ Hans, Sellano (2004) p. 68

- ^ Parker (1888) p. 10–11

- ^ a b c d 1959–, Elleman, Bruce A., (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795–1989. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. OCLC 469963841.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Glenn Melancon, "Honor in Opium? The British Declaration of War on China, 1839–1840," International History Review (1999) 21#4 pp 854–874.

- ^ "No. 19989". The London Gazette. 18 June 1841. p. 1583.

- ^ a b c Glenn Melancon (2003). Britain's China Policy and the Opium Crisis: Balancing Drugs, Violence and National Honour, 1833–1840. Ashgate. p. 126.

- ^ John K. Derden, "The British Foreign Office and Policy Formation: The 1840's," Proceedings & Papers of the Georgia Association of Historians (1981) pp 64–79.

- ^ Luscombe, Stephen. "The British Empire, Imperialism, Colonialism, Colonies". www.britishempire.co.uk. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ a b Hummel, Arthur William (1943). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period (1644–1912). Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- ^ a b Elliott, Mark (June 1990). "Bannerman and Townsman: Ethnic Tension in Nineteenth-Century Jiangnan". Late Imperial China 11 (1): 51.

- ^ Spence 1999, p. 153–155.

- ^ a b "No. 19930". The London Gazette. 15 December 1840.

- ^ Morse. p.628

- ^ a b c MacPherson 1843, pp. 312, 315, 316.

- ^ a b c d e f Dillon (2010) p. 55

- ^ a b Bulletins of State Intelligence 1841, p. 32

- ^ Bulletins of State Intelligence 1841, pp. 329–330

- ^ Bingham. pg 69–70

- ^ a b Lovell, Julia (2015). The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams, and the Making of Modern China. The Overlook Press. ISBN 1468311735.

- ^ Wakeman, p. 14

- ^ Bulletins and Other State Intelligence. 1841 p. 686

- ^ a b Bernard, p. 138–148

- ^ a b Bingham 1842, pp. 73–74

- ^ Frontier and Overseas Expeditions From India, vol. 6, p. 382

- ^ Hoiberg. p. 27–28

- ^ 1959–, Tsang, Steve Yui-Sang, (2011). A modern history of Hong Kong. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-419-1. OCLC 827739089.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bate, H. Maclear (1952). Reports from Formosa New York: E. P. Dutton. p. 174.

- ^ MacPherson 1843, p. 216, 359.

- ^ MacPherson 1843, pp. 381–385

- ^ Hall & Bernard 1846, p. 260

- ^ a b c Luscombe, Stephen. "The British Empire, Imperialism, Colonialism, Colonies". www.britishempire.co.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ a b Bulletins of State Intelligence 1842, p. 578, 594

- ^ a b Waley, Arthur (2013) p. 171

- ^ Bulletins 1842, p. 601

- ^ Rait 1903, p. 264

- ^ a b Bulletins of State Intelligence 1842, p. 918

- ^ a b c d e Hall & Bernard 1846, p. 330

- ^ Publishing, D. K. (1 October 2009). War: The Definitive Visual History. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-7566-6817-4.

- ^ Bulletins of State Intelligence 1842, p. 759, 816

- ^ a b c Rait 1903, pp. 267–268

- ^ Granville G. Loch. The Closing Events of the Campaign in China: The Operations in the Yang-tze-kiang and treaty of Nanking . London. 1843 [ 2014-07-13 ]

- ^ Rait 1903. p. 266.

- ^ Academy of Military Sciences, "History of Modern Chinese War" Section VII of the British invasion of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Military Science Press.

- ^ "The Count of Aberdeen to Sir Henry Pudding" The Jazz "History of the Chinese Empire" (Chinese translation) vol. 1, pp. 755–756.

- ^ (3) Part 5 "Diary of the Grass". Shanghai Bookstore. 2000-06-01. ISBN 7-80622-800-4.

- ^ John Makeham (2008). p. 331

- ^ Waley (1959) p. 197

- ^ Treaty Chinese humiliating first - the signing of the "Nanjing Treaty" . Chinese history theyatic networks. [2008-08-31 ] . Chinese source, used for dates only.

- ^ "Opium War" Volume 5. Shanghai People's Publishing House. 2000: 305 pages.

- ^ a b Greenwood ch.4

- ^ a b "After the Opium War: Treaty Ports and Compradors". www.library.hbs.edu. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ a b "The Nemesis — Great Britain's Secret Weapon in the Opium Wars, 1839–60". www.victorianweb.org. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ a b MSW (3 January 2017). "Qing and Opium Wars I". Weapons and Warfare. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e opiumwarexhibition (22 November 2014). "Warfare technology in the Opium War". The Opium War, 1839–1842. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ Kim Joosam "An Analysis of the Process of Modernization in East Asia and the Corresponding changes in China and Japan after the Opium Wars", Asian Study 11.3 (2009). The Korean Association of Philippine Studies. Web.

- ^ "--Welcome to Zhenhai coast defence history museum--". www.zhkhfsg.com. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ a b Hederic, p. 234

- ^ a b Cone, Daniel. An Indefensible Defense:The Incompetence of Qing Dynasty Officials in the Opium Wars, and the Consequences of Defeat. http://history.emory.edu/home/documents/endeavors/volume4/Cone.pdf

- ^ Hoiberg. p. 28–30

- ^ Bulletins of State Intelligence 1841, p. 348

- ^ Bingham 1843, p. 399

- ^ Bingham (1843), p. 72.

- ^ a b Andrade, Tonio (12 January 2016). The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-7444-6.

- ^ a b c d "The life and campaigns of Hugh, first Viscount Gough, Field-Marshal". archive.org. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ Elliott 2001, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Elliott 2001, pp. 283–284. 300–303.

- ^ CrossleySiuSutton (2006), p. 50

- ^ Jasper Ridley, Lord Palmerston, (1970) p. 248

- ^ H.G. Gelber, Harvard University Centre for European Studies Working Paper 136, 'China as Victim: The Opium War that wasn't'

- ^ Glenn Melancon (2003). Britain's China Policy and the Opium Crisis: Balancing Drugs, Violence and National Honour, 1833–1840. Ashgate. p. 126.

- ^ Miron, Jeffrey A. and Feige, Chris. The Opium Wars: Opium Legalization and Opium Consumption in China. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2005.

- ^ "Lin Zexu". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ Lee Khoon Choy (2007). "Pioneers of Modern China: Understanding the Inscrutable Chinese: Chapter 1: Fujian Rén & Lin Ze Xu: The Fuzhou Hero Who Destroyed Opium". East Asian Studies. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ "Monument to the People's Heroes". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ "Lin Zexu Memorial". chinaculture.org. Archived from the original on 13 June 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Lin Zexu Memorial Museum Ola Macau Travel Guide". olamacauguide.com. Retrieved 3 June 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Schell, Orville; John Delury (12 July 2013). "A Rising China Needs a New National Story". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ Kathleen L. Lodwick (5 February 2015). Crusaders Against Opium: Protestant Missionaries in China, 1874–1917. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-0-8131-4968-4.

- ^ Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy (2009). Opium: Uncovering the Politics of the Poppy. Harvard University Press. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-0-674-05134-8.

- ^ Dr Roland Quinault; Dr Ruth Clayton Windscheffel; Mr Roger Swift (28 July 2013). William Gladstone: New Studies and Perspectives. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 238–. ISBN 978-1-4094-8327-4.

- ^ Ms Louise Foxcroft (28 June 2013). The Making of Addiction: The 'Use and Abuse' of Opium in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-1-4094-7984-0.

- ^ William Travis Hanes; Frank Sanello (2004). Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Sourcebooks, Inc. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-1-4022-0149-3.

- ^ W. Travis Hanes III; Frank Sanello (1 February 2004). The Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Sourcebooks. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-1-4022-5205-1.

- ^ Peter Ward Fay (9 November 2000). The Opium War, 1840–1842: Barbarians in the Celestial Empire in the Early Part of the Nineteenth Century and the War by which They Forced Her Gates Ajar. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 290–. ISBN 978-0-8078-6136-3.

- ^ Anne Isba (24 August 2006). Gladstone and Women. A&C Black. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-1-85285-471-3.

- ^ David William Bebbington (1993). William Ewart Gladstone: Faith and Politics in Victorian Britain. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-0-8028-0152-4.

References and further reading

- Beeching, Jack, The Chinese Opium Wars, Hutchinson, 1975, Harcourt, 1976.

- Fairbank, John King, Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast; the Opening of the Treaty Ports, 1842–1854 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953).

- Fay, Peter Ward, The Opium War, 1840–1842: Barbarians in the Celestial Empire in the early part of the nineteenth century and the way by which they forced the gates ajar (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1975).

- Gray, Jack (2002). Rebellions and Revolutions: China from the 1800s to 2000. Short Oxford History of the Modern World. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870069-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Greenberg, Michael. British Trade and the Opening of China, 1800–42. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Studies in Economic History, 1951). Various reprints. Uses Jardine Matheson papers to detail the British side of the trade.

- Greenwood, Adrian (2015). Victoria's Scottish Lion: The Life of Colin Campbell, Lord Clyde. UK: History Press. p. 496. ISBN 0-7509-5685-2.

- Hanes, W. Travis; Sanello, Frank (2004). Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Sourcebooks. ISBN 978-1-4022-2969-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hoe, Susanna; Roebuck, Derek (1999). The Taking of Hong Kong: Charles and Clara Elliot in China Waters. Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-1145-7.

- Hsin-Pao Chang. Commissioner Lin and the Opium War. (Cambridge,: Harvard University Press, Harvard East Asian Series, 1964).

- Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Aberdeen, George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of,". Encyclopædia Britannica. I: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- Johnson, Kendall, The New Middle Kingdom: China and the Early American Romance of Free Trade (Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017 ISBN 978-1-4214-2251-0).

- Lovell, Julia, The Opium War: Drug, Dreams and the Making of China (London, Picador, 2011 ISBN 0-330-45747-0). Well referenced narrative using both Chinese and western sources and scholarship.

- Manhong Lin. China Upside Down: Currency, Society, and Ideologies, 1808–1856. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, Harvard East Asian Monographs, 2006). ISBN 0-674-02268-8. Detailed study of the economics of the trade.

- MacPherson, D. (1842). Two Years in China: Narrative of the Chinese Expedition, from Its Formation in April, 1840, Till April, 1842 : with an Appendix, Containing the Most Important of the General Orders & Despatches Published During the Above Period. London: Saunders and Otley.

- John Makeham (2008). China: The World's Oldest Living Civilization Revealed. Thames & Hudson. p. 331. ISBN 978-0-500-25142-3.

- Miron, Jeffrey A. and Feige, Chris. The Opium Wars: Opium Legalization and Opium Consumption in China. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2005.

- Polachek, James M., The Inner Opium War (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1992.) Based on court records and diaries, presents the debates among Chinese officials whether to legalise or suppress the use and trade in opium.

- Rait, Robert S. (1903). The Life and Campaigns of Hugh, First Viscount Gough, Field-Marshal. Volume 1. Westminster: Archibald Constable.

- Frontier and Overseas Expeditions From India, vol. 6, p. 382

- Wakeman, Frederic E. (1997). Strangers at the Gate: Social Disorder in South China, 1839–1861. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21239-8.

- Hummel, Arthur William (1943). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period (1644–1912). Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1999). The Search for Modern China (second ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-97351-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Waley, Arthur, The Opium War Through Chinese Eyes (London: Allen & Unwin, 1958; reprinted Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1968). Translations and narrative based on Lin's writings.

- Correspondence Relating to China (1840). London: Printed by T. R. Harrison.

- The Chinese Repository (1840). Volume 8.

- Waley, Arthur (2013) [First published 1958]. The Opium War Through Chinese Eyes. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-57665-2.

- Myers, H. Ramon; Wang, Yeh-Chien (2002), "Economic developments, 1644–1800", in Peterson Willard J. (ed.), Part One: The Ch'ing Empire to 1800, The Cambridge History of China, 9, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 563–647, ISBN 978-0-521-24334-6.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle; Siu, Helen F.; Sutton, Donald S. (2006), Empire at the Margins: Culture, Ethnicity, and Frontier in Early Modern China, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-23015-9.

- Elliot, Mark C. (2001), The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-4684-2.

- Bingham, John Elliot (1843). Narrative of the Expedition to China from the Commencement of the War to Its Termination in 1842 (2nd ed.). Volume 2. London: Henry Colburn.

- Bernard, William Dallas; Hall, William Hutcheon (1847). The Nemesis in China (3rd ed.). London: Henry Colburn.

- Dillon, Michael (2010). China: A Modern History. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-582-2.

- Compilation Group for the "History of Modern China" Series. (2000). The Opium War. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific; reprint from 1976 edition. ISBN 0-89875-150-0.

- Downs, Jacques M. (1997). The Golden Ghetto: The American Commercial Community at Canton and the Shaping of American China Policy, 1784–1844. Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh University Press; reprinted, Hong Kong University Press, 2014. ISBN 0-934223-35-1.

- Parker, Edward Harper (1888). Chinese Account of the Opium War. Shanghai

- John K. Derden, "The British Foreign Office and Policy Formation: The 1840's," Proceedings & Papers of the Georgia Association of Historians (1981) pp 64–79.

- Morse, Hosea Ballou (1910). The International Relations of the Chinese Empire. Volume 1. New York: Paragon Book Gallery.

- Headrick, Daniel R. (1979). "The Tools of Imperialism: Technology and the Expansion of European Colonial Empires in the Nineteenth Century" (PDF). The Journal of Modern History. 51 (2): 231–263. doi:10.1086/241899. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- Bulletins and Other State Intelligence. Compiled and arranged from the official documents published in the London Gazette. London: F. Watts. 1841.