Chaos (cosmogony): Difference between revisions

toc |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Greco-Roman tradition== |

==Greco-Roman tradition== |

||

Greek {{lang|grc|[[:wikt:χάος|χάος]]}} means "[[emptiness]], vast void, [[chasm]], [[abyss (religion)|abyss]]", from the verb {{lang|grc|[[wikt:χαίνω|χαίνω]]}}, "gape, be wide open, etc.", from [[Proto-Indo-European language|Proto-Indo-European]] ''{{PIE|*ǵ<sup>h</sup>eh<sub>2</sub>n}}'',<ref>[[Robert S. P. Beekes|R. S. P. Beekes]], ''Etymological Dictionary of Greek'', Brill, 2009, pp. 1614 and 1616–7.</ref> cognate to [[Old English language|Old English]] ''geanian'', "to gape", whence English ''[[:wikt:yawn|yawn]]''.<ref name=OnEtD>{{cite web|title=chaos|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=chaos&allowed_in_frame=0|publisher=[[Online Etymology Dictionary]]}}</ref> |

Greek {{lang|grc|[[:wikt:χάος|χάος]]}} means "[[emptiness]], vast void, [[chasm]],<ref>West, p. 192 line 116 '''Χάος''', "best translated Chasm"; Most, p. 13, translates ''Χάος'' as "Chasm", and notes: (n. 7): "Usually translated as 'Chaos'; but that suggests to us, misleadingly, a jumble of disordered matter, whereas Hesiod's term indicates instead a gap or opening".</ref> [[abyss (religion)|abyss]]", from the verb {{lang|grc|[[wikt:χαίνω|χαίνω]]}}, "gape, be wide open, etc.", from [[Proto-Indo-European language|Proto-Indo-European]] ''{{PIE|*ǵ<sup>h</sup>eh<sub>2</sub>n}}'',<ref>[[Robert S. P. Beekes|R. S. P. Beekes]], ''Etymological Dictionary of Greek'', Brill, 2009, pp. 1614 and 1616–7.</ref> cognate to [[Old English language|Old English]] ''geanian'', "to gape", whence English ''[[:wikt:yawn|yawn]]''.<ref name=OnEtD>{{cite web|title=chaos|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=chaos&allowed_in_frame=0|publisher=[[Online Etymology Dictionary]]}}</ref> |

||

It may also mean space, the expanse of air, and the nether abyss, infinite [[darkness]].<ref name=chaos>Lidell-Scott, ''[[A Greek–English Lexicon]]''[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Dxa%2Fos1 chaos]</ref> |

It may also mean space, the expanse of air, and the nether abyss, infinite [[darkness]].<ref name=chaos>Lidell-Scott, ''[[A Greek–English Lexicon]]''[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Dxa%2Fos1 chaos]</ref> |

||

[[Pherecydes of Syros]] (fl. 6th century BC) interprets ''chaos'' as water, like something formless which can be differentiated.<ref>{{Harvnb|Kirk|Raven|Schofield|2003|p=57}}</ref> |

[[Pherecydes of Syros]] (fl. 6th century BC) interprets ''chaos'' as water, like something formless which can be differentiated.<ref>{{Harvnb|Kirk|Raven|Schofield|2003|p=57}}</ref> |

||

[[Hesiod]] and the [[Pre-Socratic]]s use the Greek term in the context of [[cosmogony]]. Hesiod's "chaos" has been interpreted as a moving, formless mass from which the cosmos and the [[gods]] originated.<ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.artsci.lsu.edu/voegelin/EVS/Panel42001.htm| title = Hesiod as Precursor to the Presocratic Philosophers: A Voeglinian View| accessdate = 2008-12-04| author = Richard F. Moorton, Jr.| year = 2001| deadurl = yes| archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20081211142040/http://www.artsci.lsu.edu/voegelin/EVS/Panel42001.htm| archivedate = 2008-12-11| df = }}</ref> In Hesiod's opinion the origin should be indefinite and indeterminate, and it represents disorder and darkness.<ref>O. Gigon (1968) ''Der Ursprung der griechischen Philosophie. Von Hesiod bis Parmenides''. Bale. Stuttgart, Schwabe & Co. p29</ref><ref>[http://www.greekmythology.com/Books/Hesiod-Theogony/hesiod-theogony.html The Theogony of Hesiod] Transl.H.G.Evelyn White (736-744)</ref> |

[[Hesiod]] and the [[Pre-Socratic]]s use the Greek term in the context of [[cosmogony]]. Hesiod's "chaos" has been interpreted as a moving, formless mass from which the cosmos and the [[Greek pantheon|gods]] originated.<ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.artsci.lsu.edu/voegelin/EVS/Panel42001.htm| title = Hesiod as Precursor to the Presocratic Philosophers: A Voeglinian View| accessdate = 2008-12-04| author = Richard F. Moorton, Jr.| year = 2001| deadurl = yes| archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20081211142040/http://www.artsci.lsu.edu/voegelin/EVS/Panel42001.htm| archivedate = 2008-12-11| df = }}</ref> In Hesiod's opinion the origin should be indefinite and indeterminate, and it represents disorder and darkness.<ref>O. Gigon (1968) ''Der Ursprung der griechischen Philosophie. Von Hesiod bis Parmenides''. Bale. Stuttgart, Schwabe & Co. p29</ref><ref>[http://www.greekmythology.com/Books/Hesiod-Theogony/hesiod-theogony.html The Theogony of Hesiod] Transl.H.G.Evelyn White (736-744)</ref> |

||

In Hesiod, Chaos was the first thing to exist: "at first Chaos came to be" (or was)<ref>Gantz, p. 3, says "the Greek will allow both".</ref> "but next" (possibly out of Chaos) came [[Gaia (mythology)|Gaia]], [[Tartarus]], and [[Eros]] (elsewhere the son of [[Aphrodite]]).<ref>According to Gantz, p. 4: "With regard to all three of these figures—Gaia, Tartaros, and Eros—we should note that Hesiod does not say they arose ''from'' (as opposed to ''after'') Chaos, although this is often assumed." For example, Morford, p. 57, makes these three descendants of Chaos saying they came "presumably out of Chaos, just as Hesiod actually states that 'from Chaos' came Erebus and dark Night". Tripp, p. 159, says simply that Gaia, Tartarus and Eros came "out of Chaos, or together with it". Caldwell, p. 33 n. 116–122, however interprets Hesiod as saying that Chaos, Gaia, Tartarus, and Eros all "are spontaneously generated without source or cause". Later writers commonly make Eros the son of [[Aphrodite]] and [[Ares]], though several other parentages are also given, Gantz, pp. 4–5.</ref> Unambiguously born "from Chaos" were [[Erebus]] (Darkness) and [[Nyx]] (Night).<ref>Gantz, p. 4; [[Hesiod]], ''[[Theogony]]'' [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hes.+Th.+123 123].</ref> |

|||

Of the certain uses of the word ''chaos'' in [[Theogony]], in the creation the word is referring to a "gaping void" which gives birth to the sky, but later the word is referring to the gap between the earth and the sky, after their separation. A parallel can be found in the [[Book of Genesis|Genesis]]. In the beginning God creates the earth and the sky. The earth is "formless and void" (''tohu wa-bohu''), and later God divides the waters under the firmament from the waters over the firmament, and calls the firmament "heaven".<ref name=Kirk44/> |

|||

For Hesiod, Chaos, like Tartarus, though personified enough to have borne children, was also a place, far away, underground and "gloomy", beyond which lived the [[Titan (mythology)|Titans]].<ref>[[Hesiod]], ''[[Theogony]]'' [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hes.+Th.+814 814]: "And beyond, away from all the gods, live the Titans, beyond gloomy Chaos".</ref> And, like the earth, the ocean, and the upper air, it was also capable of being affected by Zeus' thunderbolts.<ref>[[Hesiod]], ''[[Theogony]]'' [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hes.+Th.+700 700].</ref> |

|||

For [[ |

For the Roman poet [[Ovid]], Chaos was an unformed mass, where all the elements were jumbled up together in a "shapeless heap".<ref>[[Ovid]], ''[[Metamorphoses]]'' [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Ov.+Met.+1.5 1.5 ff.].</ref> |

||

According to [[Hyginus]]: "From Mist (''Caligine'') came Chaos. From Chaos and Mist, came Night (''Nox''), Day (''Dies''), Darkness (''Erebus''), and Ether (''Aether'')."<ref>Hyginus, ''[[Fabulae]]'' Preface 1, translated by Smith and Trzaskoma, p. 95. According to Bremmer, [https://books.google.com/books?id=YTfxZH4QnqgC&pg=PA5 p. 5], who translates ''Caligine'' as "Darkness": "Hyginus ... started his ''Fabulae'' with a strange hodgepodge of Greek and Roman cosmogonies and early genealogies. It begins as follows: ''Ex Caligine Chaos. Ex Chao et Caligine Nox Dies Erebus Aether'' (Praefatio 1). His genealogy looks like a derivation from Hesiod, but it starts with the un-Hesiodic and un-Roman ''Caligo'', ‘Darkness’. Darkness probably did occur in a cosmogonic poem of Alcman, but it seems only fair to say that it was not prominent in Greek cosmogonies."</ref> An [[Orphism (religion)|Orphic tradition]] apparently had Chaos as the son of [[Chronus]] and [[Ananke (mythology)|Ananke]].<ref>Ogden, pp. 36–37.</ref> |

|||

In [[Aristophanes]]'s comedy ''[[The Birds (play)|Birds]]'', first there was Chaos, Night, Erebus, and Tartarus, from Night came Eros, and from Eros and Chaos came the race of birds.<ref> [[Aristophanes]], ''[[The Birds (play)|Birds]]'' [http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0019.tlg006.perseus-eng1:685-707 693–699]; Morford, pp 57–58. Caldwell, p. 2, describes this avian theogony as "comedic parody".</ref> |

|||

For Hesiod and the early Greek Olympian myth (8th century BC), Chaos was the first of the [[Greek primordial deities|primordial deities]], followed by [[Gaia (mythology)|Gaia]] (Earth), [[Tartarus]] and [[Eros]] (Love).<ref>[[Hesiod]], ''[[Theogony]]'' [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hes.+Th.+116 116–122].</ref> From Chaos came [[Erebus]] and [[Nyx]].<ref>Hesiod, ''Theogony'' [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hes.+Th.+123 123–124].</ref> |

|||

Passages in Hesiod's ''[[Theogony]]'' suggest that Chaos was located below Earth but above Tartarus.<ref>Gantz, p. 3; Hesiod, ''Theogony'' [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hes.+Th.+813 813–814], [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hes.+Th.+700 700]; cf. [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hes.+Th.+740 740].</ref> Primal Chaos was sometimes said to be the true foundation of reality, particularly by philosophers such as [[Heraclitus]]. |

Passages in Hesiod's ''[[Theogony]]'' suggest that Chaos was located below Earth but above Tartarus.<ref>Gantz, p. 3; Hesiod, ''Theogony'' [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hes.+Th.+813 813–814], [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hes.+Th.+700 700]; cf. [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hes.+Th.+740 740].</ref> Primal Chaos was sometimes said to be the true foundation of reality, particularly by philosophers such as [[Heraclitus]]. |

||

Revision as of 14:31, 3 March 2018

Chaos (Greek χάος, khaos) refers to the formless or void state preceding the creation of the universe or cosmos in the Greek creation myths, or to the initial "gap" created by the original separation of heaven and earth.[1][2][3]

Greco-Roman tradition

Greek χάος means "emptiness, vast void, chasm,[4] abyss", from the verb χαίνω, "gape, be wide open, etc.", from Proto-Indo-European *ǵheh2n,[5] cognate to Old English geanian, "to gape", whence English yawn.[6] It may also mean space, the expanse of air, and the nether abyss, infinite darkness.[7]

Pherecydes of Syros (fl. 6th century BC) interprets chaos as water, like something formless which can be differentiated.[8]

Hesiod and the Pre-Socratics use the Greek term in the context of cosmogony. Hesiod's "chaos" has been interpreted as a moving, formless mass from which the cosmos and the gods originated.[9] In Hesiod's opinion the origin should be indefinite and indeterminate, and it represents disorder and darkness.[10][11]

In Hesiod, Chaos was the first thing to exist: "at first Chaos came to be" (or was)[12] "but next" (possibly out of Chaos) came Gaia, Tartarus, and Eros (elsewhere the son of Aphrodite).[13] Unambiguously born "from Chaos" were Erebus (Darkness) and Nyx (Night).[14] For Hesiod, Chaos, like Tartarus, though personified enough to have borne children, was also a place, far away, underground and "gloomy", beyond which lived the Titans.[15] And, like the earth, the ocean, and the upper air, it was also capable of being affected by Zeus' thunderbolts.[16]

For the Roman poet Ovid, Chaos was an unformed mass, where all the elements were jumbled up together in a "shapeless heap".[17]

According to Hyginus: "From Mist (Caligine) came Chaos. From Chaos and Mist, came Night (Nox), Day (Dies), Darkness (Erebus), and Ether (Aether)."[18] An Orphic tradition apparently had Chaos as the son of Chronus and Ananke.[19]

In Aristophanes's comedy Birds, first there was Chaos, Night, Erebus, and Tartarus, from Night came Eros, and from Eros and Chaos came the race of birds.[20]

For Hesiod and the early Greek Olympian myth (8th century BC), Chaos was the first of the primordial deities, followed by Gaia (Earth), Tartarus and Eros (Love).[21] From Chaos came Erebus and Nyx.[22]

Passages in Hesiod's Theogony suggest that Chaos was located below Earth but above Tartarus.[23] Primal Chaos was sometimes said to be the true foundation of reality, particularly by philosophers such as Heraclitus.

Ovid (1st century BC), in his Metamorphoses, described Chaos as "a rude and undeveloped mass, that nothing made except a ponderous weight; and all discordant elements confused, were there congested in a shapeless heap."[24]

Fifth-century Orphic cosmogony had a "Womb of Darkness" in which the Wind lay a Cosmic Egg whence Eros was hatched, who set the universe in motion.

In the Theogony of Hesiod, Chaos is a divine primordial condition, which is the origin of the gods, and all things. It seems that in Hesiod's opinion, the origin should be indefinite and indeterminate, and it may represent infinite space, or formless matter.[7] The notion of the temporal infinity was familiar to the Greek mind from remote antiquity in the religious conception of immortality.[25] This idea of the divine as an origin influenced the first Greek philosophers.[26] The main object of the first efforts to explain the world remained the description of its growth, from a beginning. They believed that the world arose out from a primal unity, and that this substance was the permanent base of all its being. It seems that Anaximander was influenced by the traditional popular conceptions and Hesiod's thought, when he claims that the origin is apeiron (the unlimited), a divine and perpetual substance less definite than the common elements. Everything is generated from apeiron, and must return there according to necessity.[27] A popular conception of the nature of the world, was that the earth below its surface stretches down indefinitely and has its roots on or above Tartarus, the lower part of the underworld.[28] In a phrase of Xenophanes, "The upper limit of the earth borders on air, near our feet. The lower limit reaches down to the "apeiron" (i.e. the unlimited)."[28] The sources and limits of the earth, the sea, the sky, Tartarus, and all things are located in a great windy-gap, which seems to be infinite, and is a later specification of "chaos".[28][29] Primal Chaos was sometimes said to be the true foundation of reality, particularly by philosophers such as Heraclitus.

Chaoskampf

The motif of Chaoskampf (German: [ˈkaːɔsˌkampf], "struggle against chaos") is ubiquitous in myth and legend, depicting a battle of a culture hero deity with a chaos monster, often in the shape of a serpent or dragon. The same term has also been extended to parallel concepts in the religions of the ancient Near East, such as the abstract conflict of ideas in the Egyptian duality of Maat and Isfet.[citation needed]

The origins of the Chaoskampf myth most likely lie in the Proto-Indo-European religion whose descendants almost all feature some variation of the story of a storm god fighting a sea serpent representing the clash between the forces of order and chaos. Early work by German academics such as Gunkel and Bousset in comparative mythology popularized translating the mythological sea serpent as a "dragon." Indo-European examples of this mythic trope include Thor vs. Jörmungandr (Norse), Tarḫunz vs. Illuyanka (Hittite), Indra vs. Vritra (Vedic), Θraētaona vs. Aži Dahāka (Avestan), Susano'o vs. Yamata no Orochi (Japanese), Mwindo vs. Kirimu (African), and Zeus vs. Typhon (Greek) among others.[30]

Biblical tradition

This model of a primordial state of matter has been opposed by the Church Fathers from the 2nd century, who posited a creation ex nihilo by an omnipotent God.[31]

In modern biblical studies, the term chaos is commonly used in the context of the Torah and their cognate narratives in Ancient Near Eastern mythology more generally. Parallels between the Hebrew Genesis and the Babylonian Enuma Elish were established by Hermann Gunkel in 1910.[32] Besides Genesis, other books of the Old Testament, especially a number of Psalms, some passages in Isaiah and Jeremiah and the Book of Job are relevant.[33][34][35]

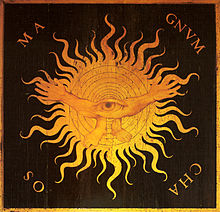

Alchemy and Hermeticism

The Greco-Roman tradition of Prima Materia, notably including the 5th and 6th century Orphic cosmogony, was merged with biblical notions (Tehom) in Christianity and inherited by alchemy and Renaissance magic.

The cosmic egg of Orphism was taken as the raw material for the alchemical magnum opus in early Greek alchemy. The first stage of the process of producing the philosopher's stone, i.e., nigredo, was identified with chaos. Because of association with the Genesis creation narrative, where "the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters" (Gen. 1:2), Chaos was further identified with the classical element of Water.

Ramon Llull (1232–1315) wrote a Liber Chaos, in which he identifies Chaos as the primal form or matter created by God. Swiss alchemist Paracelsus (1493–1541) uses chaos synonymously with "classical element" (because the primeval chaos is imagined as a formless congestion of all elements). Paracelsus thus identifies Earth as "the chaos of the gnomi", i.e., the element of the gnomes, through which these spirits move unobstructed as fish do through water, or birds through air.[36] An alchemical treatise by Heinrich Khunrath, printed in Frankfurt in 1708, was entitled Chaos.[37] The 1708 introduction to the treatise states that the treatise was written in 1597 in Magdeburg, in the author's 23rd year of practicing alchemy.[38] The treatise purports to quote Paracelsus on the point that "The light of the soul, by the will of the Triune God, made all earthly things appear from the primal Chaos."[39] Martin Ruland the Younger, in his 1612 Lexicon Alchemiae, states, "A crude mixture of matter or another name for Materia Prima is Chaos, as it is in the Beginning."

The term gas in chemistry was coined by Dutch chemist Jan Baptist van Helmont in the 17th century directly based on the Paracelsian notion of chaos. The g in gas is due to the Dutch pronunciation of this letter as a spirant, also employed to pronounce Greek χ.[40]

Modern usage

The term chaos has been adopted in modern comparative mythology and religious studies as referring to the primordial state before creation, strictly combining two separate notions of primordial waters or a primordial darkness from which a new order emerges and a primordial state as a merging of opposites, such as heaven and earth, which must be separated by a creator deity in an act of cosmogony.[41] In both cases, chaos referring to a notion of a primordial state contains the cosmos in potentia but needs to be formed by a demiurge before the world can begin its existence.

Use of chaos in the derived sense of "complete disorder or confusion" first appears in Elizabethan Early Modern English, originally implying satirical exaggeration.[42]

See also

- Chaos (mythology)

- Amatsu-Mikaboshi

- Azathoth

- Brahman

- Chaos in Cornelius Castoriadis' thought

- Chaos magic

- Chaos theory

- Cythraul

- Discordianism

- Eris (mythology)

- Ex nihilo

- Ginnungagap

- Greek primordial deities

- How to Kill a Dragon

- Hundun

- Myth of redemptive violence

- Sabazios

- Tiamat

- Tohu wa-bohu

- Void in Alain Badiou's thought

- Ymir

Notes

- ^ Euripides Fr.484, Diodorus DK68,B5,1, Apollonius Rhodius I,49 Kirk p.42

- ^ Kirk, Raven & Schofield 2003, p. 42

- ^ Kirk, Raven & Schofield 2003, p. 44

- ^ West, p. 192 line 116 Χάος, "best translated Chasm"; Most, p. 13, translates Χάος as "Chasm", and notes: (n. 7): "Usually translated as 'Chaos'; but that suggests to us, misleadingly, a jumble of disordered matter, whereas Hesiod's term indicates instead a gap or opening".

- ^ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, pp. 1614 and 1616–7.

- ^ "chaos". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b Lidell-Scott, A Greek–English Lexiconchaos

- ^ Kirk, Raven & Schofield 2003, p. 57

- ^ Richard F. Moorton, Jr. (2001). "Hesiod as Precursor to the Presocratic Philosophers: A Voeglinian View". Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ O. Gigon (1968) Der Ursprung der griechischen Philosophie. Von Hesiod bis Parmenides. Bale. Stuttgart, Schwabe & Co. p29

- ^ The Theogony of Hesiod Transl.H.G.Evelyn White (736-744)

- ^ Gantz, p. 3, says "the Greek will allow both".

- ^ According to Gantz, p. 4: "With regard to all three of these figures—Gaia, Tartaros, and Eros—we should note that Hesiod does not say they arose from (as opposed to after) Chaos, although this is often assumed." For example, Morford, p. 57, makes these three descendants of Chaos saying they came "presumably out of Chaos, just as Hesiod actually states that 'from Chaos' came Erebus and dark Night". Tripp, p. 159, says simply that Gaia, Tartarus and Eros came "out of Chaos, or together with it". Caldwell, p. 33 n. 116–122, however interprets Hesiod as saying that Chaos, Gaia, Tartarus, and Eros all "are spontaneously generated without source or cause". Later writers commonly make Eros the son of Aphrodite and Ares, though several other parentages are also given, Gantz, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Gantz, p. 4; Hesiod, Theogony 123.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 814: "And beyond, away from all the gods, live the Titans, beyond gloomy Chaos".

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 700.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.5 ff..

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae Preface 1, translated by Smith and Trzaskoma, p. 95. According to Bremmer, p. 5, who translates Caligine as "Darkness": "Hyginus ... started his Fabulae with a strange hodgepodge of Greek and Roman cosmogonies and early genealogies. It begins as follows: Ex Caligine Chaos. Ex Chao et Caligine Nox Dies Erebus Aether (Praefatio 1). His genealogy looks like a derivation from Hesiod, but it starts with the un-Hesiodic and un-Roman Caligo, ‘Darkness’. Darkness probably did occur in a cosmogonic poem of Alcman, but it seems only fair to say that it was not prominent in Greek cosmogonies."

- ^ Ogden, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Aristophanes, Birds 693–699; Morford, pp 57–58. Caldwell, p. 2, describes this avian theogony as "comedic parody".

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 116–122.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 123–124.

- ^ Gantz, p. 3; Hesiod, Theogony 813–814, 700; cf. 740.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses 1.5–9

- Ante mare et terras et quod tegit omnia caelum

- unus erat toto naturae vultus in orbe,

- quem dixere chaos: rudis indigestaque moles

- nec quicquam nisi pondus iners congestaque eodem

- non bene iunctarum discordia semina rerum.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Guthrie59was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ W. Jaeger (1953). The Theology of the early Greek philosophers. The Gifford lectures p.33:Nilsson, Vol I, p.743

- ^ W. K. Guthrie (1952): The Presocratic World-picture p.87: Nilsson, Vol I, p.743

- ^ a b c Kirk, Raven & Schofield 2003, pp. 9, 10, 20

- ^ Hesiod Theogony 740-765: [1]

- ^ Watkins, Calvert (1995). How to Kill a Dragon. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514413-0

- ^ Gerhard May, Schöpfung aus dem Nichts. Die Entstehung der Lehre von der creatio ex nihilo, AKG 48, Berlin / New York, 1978, 151f.

- ^ H. Gunkel, Genesis, HKAT I.1, Göttingen, 1910.

- ^ Michaela Bauks, Chaos / Chaoskampf, WiBiLex – Das Bibellexikon (2006).

- ^ Michaela Bauks, Die Welt am Anfang. Zum Verhältnis von Vorwelt und Weltentstehung in Gen 1 und in der altorientalischen Literatur (WMANT 74), Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1997.

- ^ Michaela Bauks, ''Chaos' als Metapher für die Gefährdung der Weltordnung', in: B. Janowski / B. Ego, Das biblische Weltbild und seine altorientalischen Kontexte (FAT 32), Tübingen, 2001, 431-464.

- ^ De Nymphis etc. Wks. 1658 II. 391

- ^ Khunrath, Heinrich (1708). Vom Hylealischen, das ist Pri-materialischen Catholischen oder Allgemeinen Natürlichen Chaos der naturgemässen Alchymiae und Alchymisten: Confessio.

- ^ Urszula Szulakowska, The alchemy of light: geometry and optics in late Renaissance alchemical illustration, vol. 10 of Symbola et Emblemata - Studies in Renaissance and Baroque Symbolism, BRILL, 2000, ISBN 978-90-04-11690-0, ch. 7 (pp. 79ff).

- ^ Szulakowska (2000), p. 91, quoting Chaos p. 68.

- ^ "halitum illum Gas vocavi, non longe a Chao veterum secretum." Ortus Medicinæ, ed. 1652, p. 59a, cited after the Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Mircea Eliade, article "Chaos" in Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3rd ed. vol. 1, Tübingen, 1957, 1640f.

- ^ Stephen Gosson, The schoole of abuse, containing a plesaunt inuectiue against poets, pipers, plaiers, iesters and such like caterpillers of a commonwelth (1579), p. 53 (cited after OED): "They make their volumes no better than [...] a huge Chaos of foule disorder."

References

- G. S. Kirk; J. E. Raven; M. Schofield (2003). The Presocratic philosophers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-27455-9.

- Clifford, Richard J, "Creation and Destruction: A Reappraisal of the Chaoskampf Theory in the Old Testament", Catholic Biblical Quarterly, 2007.

- Day, John, God's conflict with the dragon and the sea: echoes of a Canaanite myth in the Old Testament, Cambridge Oriental Publications, 1985, ISBN 978-0-521-25600-1.

- Gantz, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0801853609 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0801853623 (Vol. 2).

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Chaos"

- Wyatt, Nick, Arms and the King: The Earliest Allusions to the Chaoskampf Motif and their Implications for the Interpretation of the Ugaritic and Biblical Traditions (1998), republished in There's such divinity doth hedge a king: selected essays of Nicolas Wyatt on royal ideology in Ugaritic and Old Testament literature, Society for Old Testament Study monographs, Ashgate Publishing, 2005, ISBN 978-0-7546-5330-1, 151-190.