Barotseland

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Kingdom of Barotseland | |

|---|---|

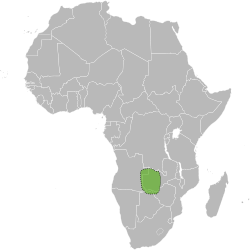

Map of Barotseland within Africa | |

| Common languages | Lozi, English |

| Area | |

• Total | 368,823 km2 (142,403 sq mi) |

| Person | muLozi, Murotse |

|---|---|

| People | baLozi, Barotse |

| Language | Silozi, Rozi |

| Country | Barotseland, Bulozi |

Barotseland (Lozi: Mubuso Bulozi) is an unrecognized kingdom between Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Angola. It is the homeland of the Lozi people or Barotse,[1] or Malozi, who are a unified group of over 20 individual formerly diverse tribes related through kinship, whose original branch are the Luyi (Maluyi), and also assimilated Southern Sotho tribe of South Africa known as the Makololo.[2][3]

The Barotse speak Silozi, a language most closely related to Sesotho. Barotseland covers an area of 126,386 square kilometres, but is estimated to have been twice as large at certain points in its history.[4] Once an empire, the Kingdom stretched into Namibia and Angola and included other parts of Zambia, including its central Copperbelt Province, south-west of the Democratic Republic of Congo's Katanga Province.[5]

Under the British colonial administration, Barotseland was a Protectorate of the British Crown from the late 19th-century. The Litunga, the Lozi word for the king of Barotseland, had negotiated agreements, first with the British South African Company (BSAC), and then with the British government that ensured the kingdom maintained much of its traditional authority according to the Litunga. Barotseland was essentially a nation-state, a protectorate within the larger protectorate of Northern Rhodesia. In return for this protectorate status, the Litunga gave the BSAC mineral exploration rights in Barotseland.[6]

In 1964, Barotseland became part of Zambia when that country achieved independence. However, some people claim that Zambia has violated the Barotseland Agreement 1964, and seek independence from Zambia. In 2012, a group of traditional Lozi leaders, calling itself the Barotseland National Council, called for independence; other tribal chieftains oppose secession, however.[7]

Geography

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

Its heartland is the Barotse Floodplain on the upper Zambezi River,[8] also known as Bulozi or Lyondo, but it includes the surrounding higher ground of the plateau comprising all of what was the Western Province of Zambia. In pre-colonial times, Barotseland included some neighbouring parts of what are now the Northwestern, Central and Southern Province as well as Caprivi in northeastern Namibia and parts of southeastern Angola beyond the Cuando or Mashi River.

History

Origins

It is believed that the Barotse state was founded by Queen Mbuywamwambwa, the Lozi matriarch, over 500 years ago.[9] Its people were migrants from the Congo. Other ethnic groupings that constitute the current Barotse kingdom migrated from South Africa, Angola, Zimbabwe, Namibia and Congo. The Barotse (the Lozi) reached the Zambezi River in the 17th century and their kingdom grew until it comprised some 25 peoples from Southern Rhodesia to the Congo and from Angola to the Kafue River. At the time, Barotseland was already a monarchy, when Lealui and Limulunga were seasonal capitals of the Lozi kings.[10]

A detailed investigation into the history of the Barotse was carried out in 1939 in connection with the Balovale Dispute, see below.[11]

In 1845 Barotseland had been conquered by the Makalolo (Kololo) from Lesotho[2] – which is why the Barotse language, Silozi, is a variant of Sesotho. The Makololo were in power when Livingstone visited Barotseland, but after thirty years the Luyi successfully overthrew the Kololo king.[12]

British colonisation

Barotseland's status at the onset of the colonial era differed from the other regions which became Zambia. It was the first territory north of the Zambezi to sign a minerals concession and protectorate agreement with the British South Africa Company (BSAC) of Cecil Rhodes.

By 1880, the kingdom was stabilised and King Lewanika signed a treaty on 26 June 1889 to provide the kingdom international recognition as a State. After the discovery of diamonds, King Lewanika began trading with Europe. The first trade concession was signed on 27 June 1889 with Harry Ware, in return King Lewanika and his kingdom were to be protected. Ware transferred his concession to Cecil Rhodes of the British South Africa Company. Seeking the improvement of the military protection and with the intention to sign a treaty with the British Government, King Lewanika signed on 26 June 1890 the Lochner concession putting Barotseland under the protection of the British South Africa Company. At that time, there was European administration in Southern Rhodesia, in Nyasaland further East, and the beginnings of European administration in what was then called North-Eastern Rhodesia (centred on Fort Jameson, now Chipata) and also North-Western Rhodesia - basically Barotseland. Later, these two were administratively combined as simply "Northern Rhodesia", later divided up in five Provinces and Barotseland, which was treated slightly differently from the rest.[3]

Later Lewanika protested to London and to Queen Victoria that the BSAC agents had misrepresented the terms of the concession,[13] but his protests fell on deaf ears,[14] and in 1899 the United Kingdom proclaimed a protectorate and governed it as part of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia.[15]

Balovale Dispute

In the 1930s, there was trouble between the Barotse and the Balovale and Balunda tribes who occupied the land to the north of the land occupied by the Barotse. The Barotse claimed that these were vassal tribes, while they claimed that they were not. Eventually, the Government set up a Commission to adjudicate, and the Barotse lost.[11]

Barotseland Agreement 1964

On 18 May 1964, the Litunga and Kenneth Kaunda Prime Minister of Northern Rhodesia signed the "Barotseland Agreement 1964"[16][17] which established Barotseland's position within Zambia in place of the earlier agreement between Barotseland and the British Government. The agreement was based on a long history of close social, economic and political interactions, but granted significant continued autonomy to Barotseland. The Barotseland Agreement granted Barotse authorities local self-governance rights and rights to be consulted on specified matters, including over land, natural resources and local government. It also established the Litunga of Barotseland as "the principal local authority for the government and administration of Barotseland", that he would remain in control of the "Barotse Native Government", the "Barotse Native Authorities", the courts known as the "Barotse Native Courts", "matters relating to local government", "land", "forests", "fishing", "control of hunting", "game preservation", the "Barotse native treasury", the supply of beer and "local taxation". There was also to be no appeal from Barotseland's courts to the courts of Zambia.[18]

Within a year of taking office as president of the newly independent Zambia on 24 October 1964, President Kenneth Kaunda began to introduce various acts that abrogated most of the powers allotted to Barotseland under the agreement.[6] Notably, the Local Government Act of 1965 abolished the traditional institutions that had governed Barotseland and brought the kingdom under the administration of a uniform local government system. Then in 1969, the Zambian Parliament passed the Constitutional Amendment Act, annulling the Barotseland Agreement of 1964. Later that year the government changed Barotseland's name to Western Province and announced that all provinces would be treated "equally". The agreement's dissolution and the stubbornness of successive governments in ignoring repeated calls to restore it have fuelled the region's ongoing tension.[6] One of the reasons why Kenneth Kaunda "revoked" the United Kingdom's Zambia Independence Act is reported to be that it called for the continuation of Barotseland.[19]

Barotseland independentists continued to lobby to be treated as a separate state and was given substantial autonomy within the later states, Northern Rhodesia and independent Zambia. At the pre-Independence talks, the Barotse simply asked for a continuation of "Queen Victoria's protection".[20]

Post-colonial era

A desire to secede was expressed from time to time, causing some friction with the government of Kenneth Kaunda, reflected in Kaunda changing the name from Barotseland Province to Western Province, and subsequently tearing up the 1964 Agreement. According to Barotse activists' views, the government in Lusaka also starved Barotseland of development – it has only one tarred road into the centre, from Lusaka to the provincial capital of Mongu, and lacks the kind of state infrastructure projects found in other provinces. Electricity supplies are erratic, relying on an ageing connection[21] to the hydroelectric plant at Kariba. Consequently, secessionist views are still aired from time to time.[15][22]

1993 Zambian High Court judgment

In an effort to solve the Barotseland issue within the legal framework the Republic of Zambia, His Majesty King Ilute Yeta III, took the matter to the High Court of Zambia, in which he sought for an interpretation of Article 4 and 8 of the Barotseland Agreement. On behalf of the Republic of Zambia, by then Attorney General, Mwelwa Chibesakunda, in the High Court clearly stated that the Barotseland Agreement was abrogated and terminated. On 4 December 1991, in a landmark Ruling, the High Court of Zambia ruled[23] that the Barotseland Agreement 1964 was abrogated, and no longer exists. According to Bartose independentists, the judgment[24] showed that the Zambian Government violated and rendered the Barotseland Agreement null and void.

This clearly meant that there is no relationship between the two nations and there is nothing people can do to mend the broken relationship between Zambia and Barotseland, because the High Court had clearly stated that the Barotseland Agreement was terminated by introducing amendments to the laws.

What remains now is an act of illegal occupation; Zambia has terminated the agreement and yet continues to enjoy the privileges and rights contained in the Barotseland Agreement.

Pro-independence news website The Barotseland Post claimed that dissatisfaction grew.[25][26]

2012 call for independence

In 2012, a Barotseland National Council accepted Zambia's abrogation of the Barotseland Agreement 1964, alleging to terminate the treaty by which Barotseland initially joined Zambia.[7]

In 2013, Barotseland became a member of the UNPO, the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization,[3] joining Tibet and Taiwan at this international organisation dedicated to giving a voice to peoples who are currently unrepresented at the United Nations. Many modern States, including Estonia, Latvia, Armenia and East Timor, were former members of the UNPO.

Due to continuing human rights violations on the part of Zambia, in 2013 the Barotseland National Freedom Alliance also petitioned the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights in Banjul to examine Zambia's violations. This matter is currently being examined by the commission.[27]

Politics

Institutions

The national flag of Barotseland has a red field and a white stripe.[28]

The traditional constitutional monarchy of Barotseland has Nilotic origins[clarification needed] with the kingdom originally divided into north and south. The north being ruled by a man, the King, called the Litunga meaning "keeper" or "guardian of the earth", and the south is ruled by a woman, Litunga la Mboela or Mulena Mukwai, "Queen of the south". Both are allegedly directly descended from the ancient Litunga Mulambwa who ruled at the turn of the nineteenth century and through his grandson, Litunga Lewanika who ruled from 1878–1916, with one break in 1884–1885, who restored the traditions of the Lozi political economy in the arena of the invasion by the Makololo, internal competition, external threats such as that posed by the Matabele and the spread of European colonialism.[14]

The government of Barotseland is the Kuta, presided over by the Ngambela (Prime Minister).[29][citation needed]

Current situation

Activists claim Barotseland is now theoretically independent from Zambia, on the basis of the Zambian High Court ruling (see below) that the 1964 Agreement was unilaterally abrogated[30] by Zambia as being null and void (see above) – i.e., Zambia washed its hands of Barotseland, which therefore reverted to the situation that existed before Zambian Independence; i.e. that Barotseland remains a Protectorate of Great Britain. However, Britain does not want to get involved.[31][citation needed]

Political parties

In the 1962 elections, the Barotse National Party was established to contest the two Barotseland districts, as part of an electoral alliance with the United Federal Party. In both districts, the BNP candidate heavily lost to the UNIP candidate.[32]

Currently, there are three groups who claim to represent Barotseland. In January 2012, the president of Zambia, Michael Sata, met the representatives of the three groups at the Zambian State House in Lusaka. The groups are Linyungandambo, Barotse Freedom Movement (BFM), and the Movement for the Restoration of Barotseland.[33] Experts have said that these three groups may become political parties should Barotseland gain independence. Fighting between the three groups has already surfaced. An article which appeared on the Zambian Watchdog, purported to be authored by a BFM representative, condemned the activities of the Linyungandambo group.[34] The BFM accused the Linyungandambo of having set up Barotseland Government portal website without consultations, and included BFM members in the purported Barotseland Government without their consents, and in disregard of the effort being made by Sata to find a lasting solution. The author, Shuwanga Shuwanga, stated that Linyungandambo had refused to work with the BFM back in 2011.

The various activist groups championing the self-determination of Barotseland have since formed one umbrella organisation called the Barotse National Freedom Alliance (BNFA) which is headed by the former Ngambela of Barotseland (Prime Minister) Clement W. Sinyinda.[35][36]

Public protests and demonstrations

2010

Two protesters were shot and killed when police opened fire on a crowd in Mongu, Western Province. A previously unknown group the Barotse Freedom Movement (BFM) organised the protest to raise awareness about the need to restore the 1964 Barotseland Agreement. Police immediately moved in as protesters gathered in the morning for the protest and dispersed the gathering saying it is illegal.[37]

2011

On 14 January 2011, thousands of Mongu residents in Western Province most of them youths rioted demanding the restoration of the Barotseland Agreement of 1964. During the riot at least two people were left dead while about 120 were arrested, charged with treason and detained Mumbwa Prisons for nine months.

Ngambela of Barotseland Maxwell Mututwa, Ex Prime Minister of Barotseland was sent in 2011 to prison at the age of 92 by the State of Zambia following the riots in Mongu, Barotseland.[38]

2012

Hundreds of people were arrested and prosecuted over 14 January 2011 riots that left at least two dead and several others injured.

2014

Barotseland Administrator General, Hon. Afumba Mombotwa and three other members of the Barotseland Provisional Government were arrested by Zambian police and spirited away to Mumbwa Prison, and then to Kabwe Prison, and charged that on unknown date but between 1 March 2012 and 20 August 2013 while in Sioma district the four, Hon. Afumba Mombotwa, Hon. Kalima Inambao, Hon. Pelekelo Kalima and Hon. Paul Masiye jointly acting together with unknown people conspired to secede "Western Province" (Barotseland) from the rest of Zambia. On 26 January 2015, the Mwembeshi magistrate court ruled that their case be committed to Kabwe High court for commencement of trial, the prisoners having been in maximum incarceration since 5 December 2014.[39]

References

- ^ The prefixes "Ma-" (singular) or "Ba-" (plural) indicate "a man / the people/tribe of"; "Lozi" or "-rotse" are different interpretations/spellings of the same word. "Si-" indicates the language.

- ^ a b Phiri, Bizeck J. (2005). "Lozi Kingdom and the Kololo". In Shillington, Kevin (ed.). Encyclopedia of African History, Volume II, H-O. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn (Routledge). pp. 851–852. ISBN 978-1-57958-454-2.

- ^ a b c "Barotseland". Unrepresented Peoples and Nations Organization. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014.

- ^ "Politics and Economics of Barotseland - Kuomboka Geographic". sites.google.com. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Katulwende, Malama (2005). Bitterness (An African Novel from Zambia). Mondial. ISBN 978-1-59569-031-9.

- ^ a b c "All shook up: Zambia's president Michael Sata broke a 2011 campaign promise to restore the Barotseland kingdom's autonomy". Good Governance Africa. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Barotseland kingdom seeks to leave Zambia". BBC News. 29 March 2012.

- ^ Silvius, Marcel J.; Oneka, M.; Verhagen, A. (2000). "Wetlands: lifeline for people at the edge". Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Part B: Hydrology, Oceans and Atmosphere. 25 (7/8): 645–652. Bibcode:2000PCEB...25..645S. doi:10.1016/S1464-1909(00)00079-4.

- ^ Caplan, Gerald L. (October 1968). "Barotseland: the secessionist challenge to Zambia". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 6 (3): 343–360. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00017456. ISSN 1469-7777.

- ^ "UNPO: Barotseland". unpo.org. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ a b "The Balovale Dispute 1939–1941". Archived from the original on 23 April 2014.

- ^ Gann, Lewis H.; Duignan, Peter (1999). Africa and the world: An introduction to the history of sub-Saharan Africa from antiquity to 1840. University Press of America. p. 413–414. ISBN 0-7618-1520-1.

- ^ Lewanika wrote to Queen Victoria, "My country is your blanket, and my people are the fleas in that blanket."

- ^ a b Clay, G. C. R. (1968). Your Friend, Lewanika: the life and times of Lubosi Lewanika, Litunga of Barotseland 1842 to 1916. London: Chatto & Windus.

- ^ a b Camerapix: "Spectrum Guide to Zambia." Camerapix International Publishing, Nairobi, 1996.

- ^ "Barotseland Agreement 1964 Document". The Lusaka Times. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011.

- ^ "THE BAROTSELAND AGREEMENT 1964". www.barotseland.info. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ "THE BAROTSELAND AGREEMENT 1964". barotseland.info. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ "Zambia Independence Act 1964" (PDF). Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ "Gervas Clay | Home". www.spanglefish.com. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ African languages in general do not have a word for "maintenance"

- ^ "Ngambela on BBC: we are forming our own Barotse country". Zambian Watchdog. 29 March 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2013.

- ^ "Barotseland Post". barotsepost.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Barotseland Post". barotsepost.com. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ "Barotseland Post". barotsepost.com. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ "Zambian government's desperation over the people of Barotseland's Banjul petition". bnfa.info. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ "August 16, 2016".

- ^ B.D, Madzudzo, E. ; Mulanda, A. ; Nagoli, J. ; Lunda, J. ; Ratner (1 January 2013). A Governance analysis of the Barotse Floodplain System, Zambia: Identifying obstacles and opportunities. WorldFish.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Barotseland Post". barotsepost.com. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ "Facebook Groups". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Robert Rotberg, "Inconclusive Election in Northern Rhodesia." Africa Report, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Dec., 1962)

- ^ "President Sata officially makes the Barotseland Agreement of 1964 public". Lusaka Times. 15 January 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012.

- ^ +. "BFM fights Linyungandambo freedom fighters, puts hope in Sata". zambianwatchdog.com. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

{{cite web}}:|author=has numeric name (help) - ^ "About Us". Barotse National Freedom Alliance (BNFA). Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ Mukuyoyisa, Mukunyandela wa Nyandi (26 November 2013). "Barotse National Freedom Alliance makes a presentation in Cape Town". Zambian Eye. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014.

- ^ "APJ Vol 1 No 4". Issuu. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Zambia | Global Information Society Watch". www.giswatch.org. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Barotseland Post". barotsepost.com. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

External links