User:Muninnkorp/sandbox

In Italy, the impacts of climate change are currently being felt on a local level, as the country is in the front line when it comes to its affects. With an increase in extreme events such as rising temperatures, more frequent flooding, an increase in extreme weather events, etc., Italy faces many challenges due to their close proximity to the Mediterranean sea.

One such case of the impact of climate change is the need for the preservation of the well known coastal city of Venice, which is destined to disappear in the coming years if the predicted scenarios become a reality. The economic, social, and environmental impacts that climate change creates, and an increasingly problematic death toll from the health risks that come with climate change will be a great challenge for Italy along with the rest of the world in the decades to come.

Italy is not the first nation to implement action plans and has been timid on this issue for years. But as a result of the impacts of climate change that affect it in particular, Italy is taking this challenge more seriously. For example, it was the first country to make education on climate change compulsory, or to include "protection of the environment, biodiversity and ecosystems" in the text in order to "protect future generations".[1]

Moreover, Italy is present on the international scene regarding the environment, such as the Paris Agreement, the EU Adaptation Strategy or the signing of a treaty between France and Italy for a reinforced bilateral cooperation which evokes many aspects and in particular a common commitment in favor of sustainable development, the defense of the climate and biodiversity, as well as the protection of the Mediterranean and the Alpine Arc.[2]

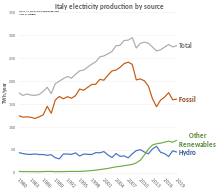

Italy is trying to adapt its consumption for a greener planet, notably by turning to renewable energies and gradually eliminating fossil fuels.

Greenhouse gas emissions

Energy consumption

Energy in Italy comes mostly from fossil fuels. Among the most used resources are petroleum (mostly used for the transport sector), natural gas (used for electric energy production and heating), coal and renewables. Italy has few energy resources, and most supplies are imported.[3]

An important share of its electricity is imported, mainly from Switzerland and France. The share of primary energy dedicated to electricity production is above 35%,[4] and has grown steadily since the 1970s.

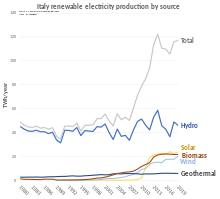

Electricity is produced mainly from natural gas, which accounts for the source of more than half of the total final electric energy produced. Another important source is hydroelectric power, which was practically the only source of electricity until 1960. Wind and solar power grew rapidly between 2010 and 2013 thanks to high incentives. Italy is one of the world's largest producers of renewable energy.[5]

Energy in Italy come mostly from fossil fuels. Among the most used resources are petroleum (mostly used for the transport sector), natural gas (used for electric energy production and heating), coal and renewables. Electricity is produced mainly from natural gas, which accounts for the source of more than half of the total final electric energy produced. Another important source is hydroelectric power, which was practically the only source of electricity until 1960. The first power plant in continental Europe was inaugurated in Milan in 1883.[7]

Eni, with operations in 79 countries, is considered one of the seven "Supermajor" oil companies in the world, and one of the world's largest industrial companies.[8] The Val d'Agri area, Basilicata, hosts the largest onshore hydrocarbon field in Europe.[9] Moderate natural gas reserves, mainly in the Po Valley and offshore Adriatic Sea, have been discovered in recent years and constitute an important mineral resource.[10]

In the last decade, Italy has become one of the world's largest producers of renewable energy, ranking as the second largest producer in the European Union and the ninth in the world. Wind power, hydroelectricity, and geothermal power are also important sources of electricity in the country. Italy was the first country in the world to exploit geothermal energy to produce electricity.[11] The first Italian geothermal power plant was built in Tuscany, which is where all currently active geothermal plants in Italy are located. In 2014 the geothermal production was 5.92 TWh.[12]

Solar energy production alone accounted for almost 9% of the total electric production in the country in 2014, making Italy the country with the highest contribution from solar energy in the world.[5] The Montalto di Castro Photovoltaic Power Station, completed in 2010, is the largest photovoltaic power station in Italy with 85 MW. Other examples of large PV plants in Italy are San Bellino (70.6 MW), Cellino san Marco (42.7 MW) and Sant’ Alberto (34.6 MW).[13]

Renewable sources account for the 27.5% of all electricity produced in Italy, with hydro alone reaching 12.6%, followed by solar at 5.7%, wind at 4.1%, bioenergy at 3.5%, and geothermal at 1.6%.[14] The rest of the national demand is covered by fossil fuels (38.2% natural gas, 13% coal, 8.4% oil) and by imports.[14]

Italy has managed four nuclear reactors until the 1980s, but in 1987, after the Chernobyl disaster, a large majority of Italians passed a referendum opting for phasing out nuclear power in Italy. The government responded by closing existing nuclear power plants and stopping work on projects underway, continuing to work to the nuclear energy program abroad instead. The national power company Enel operates seven nuclear reactors in Spain (through Endesa) and four in Slovakia (through Slovenské elektrárne),[15] and in 2005 made an agreement with Électricité de France for a nuclear reactor in France.[16] With these agreements, Italy has managed to access nuclear power and direct involvement in design, construction, and operation of the plants without placing reactors on Italian territory.[16]

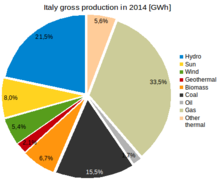

In 2014 Italy consumed 291.083 TWh (4,790 kWh/person) in electricity, consumption in household were 1057 kWh/person.[12] Italy is a net importer of electricity: the country imported 46,747.5 GWh and exported 3,031.1 GWh in 2014. Gross production in 2014 was 279.8 TWh. The main power sources are natural gas and hydroelectricity.[12]

Italy has no nuclear power since it was banished in 1987 by referendum. Italy was the first country to exploit geothermal energy to produce electricity.[11] The first Italian geothermal power plant was built in Tuscany, which is where all currently active geothermal plants in Italy are located. In 2014 the geothermal production was 5.92 TWh.[12]

| Hydroelectric | 60.256 | 21.5% |

| Thermal | 176.171 | - |

| of which by Geothermal | 5.919 | 2.1% |

| of which by Natural Gas | 93.637 | 33.5% |

| of which by Coal | 43.455 | 15.5% |

| of which by Oil | 4.764 | 1.7% |

| of which by Biomass | 18.732 | 6.7% |

| Wind | 15.178 | 5.4% |

| Solar | 22.306 | 8.0% |

Transportation

The Italian rail network is extensive, especially in the north, and it includes a high-speed rail network that joins the major cities of Italy from Naples through northern cities such as Milan and Turin. Italy has 2,507 people and 12.46 km2 per kilometer of rail track, giving Italy the world's 13th largest rail network.[20] Italy has 11 rail border crossings over the Alpine mountains with its neighbouring countries.

Higher-speed trains are divided into three categories: Frecciarossa (English: red arrow) trains operate at a maximum speed of 300 km/h (186 mph) on dedicated high-speed tracks; Frecciargento (English: silver arrow) trains operate at a maximum speed of 250 km/h (155 mph) on both high-speed and mainline tracks; and Frecciabianca (English: white arrow) trains operate on high-speed regional lines at a maximum speed of 200 km/h (124 mph).

The Italian railway system has a length of 19,394 km (12,051 mi), of which 18,071 km (11,229 mi) standard gauge and 11,322 km (7,035 mi) electrified. The active lines are 16,723 km (10,391 mi).[21] The network is recently growing with the construction of the new high-speed rail network. The narrow gauge tracks are:

- 112 km (70 mi) of 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) gauge (all electrified);

- 1,211 km (752 mi) of 950 mm (3 ft 1+3⁄8 in) gauge (of which 153 km (95 mi) electrified).

A major part of the Italian rail network is managed and operated by Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane, a state owned company. Other regional agencies, mostly owned by public entities such as regional governments, operate on the Italian network. The rail tracks and infrastructure are managed by Rete Ferroviaria Italiana. The Italian railways are subsidised by the government, receiving €8.1 billion in 2009.[22]

Travellers who often make use of the railway during their stay in Italy might use Rail Passes, such as the European Inter-Rail or Italy's national and regional passes. These rail passes allow travellers the freedom to use regional trains during the validity period, but all high-speed and intercity trains require a 10-euro reservation fee. Regional passes, such as "Io viaggio ovunque Lombardia", offer one-day, multiple-day and monthly period of validity. There are also saver passes for adults, who travel as a group, with savings up to 20%. Foreign travellers should purchase these passes in advance, so that the passes could be delivered by post prior to the trip. When using the rail passes, the date of travel needs to be filled in before boarding the trains.[23]

Major works to increase the commercial speed of the trains already started in 1967: the Rome-Florence "super-direct" line was built for trains up to 230 km/h (143 mph), and reduced the journey time to less than two hours. The Florence–Rome high-speed railway was the first high-speed line opened in Europe when more than half of it opened in 1977.

In 2009 a new high-speed line linking Milan and Turin, operating at 300 km/h (186 mph), opened to passenger traffic, reducing the journey time from two hours to one hour. In the same year, the Milan-Bologna line was open, reducing the journey time to 55 minutes. Also the Bologna-Florence high-speed line was upgraded to 300 km/h (186 mph) for a journey time of 35 minutes.

Since then, it is possible to travel from Turin to Salerno (ca. 950 km (590 mi)) in less than five hours. More than 100 trains per day are operated.[25]

The main public operator of high-speed trains (alta velocità AV, formerly Eurostar Italia) is Trenitalia, part of FSI. Trains are divided into three categories (called "Le Frecce"): Frecciarossa ("Red arrow") trains operate at a maximum of 300 km/h (186 mph) on dedicated high-speed tracks; Frecciargento (Silver arrow) trains operate at a maximum of 250 km/h (155 mph) on both high-speed and mainline tracks; Frecciabianca (White arrow) trains operate at a maximum of 200 km/h (124 mph) on mainline tracks only.[26]

Since 2012, a new and Italy's first private train operator, NTV (branded as Italo), run high-speed services in competition with Trenitalia. Even nowadays, Italy is the only country in Europe with a private high-speed train operator.

Construction of the Milan-Venice high-speed line has begun in 2013 and in 2016 the Milan-Treviglio section has been opened to passenger traffic; the Milan-Genoa high-speed line (Terzo Valico dei Giovi) is also under construction.

Today it is possible to travel from Rome to Milan in less than three hours (2h 55') with the Frecciarossa 1000, the new high-speed train. To cover this route, there's a train every 30 minutes.

With the introduction of high-speed trains, intercity trains are limited to few services per day on mainline and regional tracks.

The daytime services (InterCity IC), while not frequent and limited to one or two trains per route, are essential in providing access to cities and towns off the railway's mainline network. The main routes are Trieste to Rome (stopping at Venice, Bologna, Prato, Florence and Arezzo), Milan to Rome (stopping at Genoa, La Spezia, Pisa and Livorno / stopping at Parma, Modena, Bologna, Prato, Florence and Arezzo), Bologna to Lecce (stopping at Rimini, Ancona, Pescara, Bari and Brindisi) and Rome to Reggio di Calabria (stopping at Latina and Naples). In addition, the Intercity trains provide a more economical means of long-distance rail travel within Italy.

The night trains (Intercity Notte ICN) have sleeper compartments and washrooms, but no showers on board. Main routes are Rome to Bolzano/Bozen (calling at Florence, Bologna, Verona, Rovereto and Trento), Milan to Lecce (calling at Piacenza, Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, Bologna, Faenza, Forlì, Cesena, Rimini, Ancona, Pescara, Bari and Brindisi), Turin to Lecce (calling at Alessandria, Voghera, Piacenza, Parma, Bologna, Rimini, Pescara, Termoli, San Severo,Foggia, Barletta, Bisceglie, Molfetta, Bari, Monopoli, Fasano, Ostuni and Brindisi) and Reggio di Calabria to Turin (calling at Naples, Rome, Livorno, La Spezia and Genova). Most portions of these ICN services run during the night; since most services take 10 to 15 hours to complete a one-way journey, their day-time portion provide extra train connections to complement with the Intercity services.

There are a total of 86 intercity trains running within Italy per day.

Trenitalia operates regional services (both fast veloce RGV and stopping REG) throughout Italy.

Regional train agencies exist: their train schedules are largely connected to and shown on Trenitalia, and tickets for such train services can be purchased through Trenitalia's national network. Other regional agencies have separate ticket systems which are not mutually exchangeable with that of Trenitalia. These "regional" tickets could be purchased at local newsagents or tobacco stores instead.

- Trentino-Alto Adige / Trentino-Südtirol: Südtirol Bahn (South Tyrol Railway) runs regional services on Ala/Ahl-am-Etsch to Bolzano/Bozen (calling at Rovereto/Rofreit, Trento/Trient and Mezzocorona/Kronmetz), Bolzano/Bozen to Merano/Meran, Bressanone/Brixen to San Candido/Innichen, and a direct "Tirol regional express REX" service between Bolzano/Bozen in Italy and Innsbruck in Austria.

- Veneto: Sistemi Territoriali runs regional trains in Veneto region.

- Lombardy: Trenord runs the Malpensa Express airport train, many Milan's suburban lines and most regional train services in Lombardy. Trenord also co-operates with DB and ÖBB on the EuroCity Verona-Munich service, and with SBB CFF FFS (joint-venture TiLo) on the regional Milan-Bellinzona service.

- Emilia-Romagna: Trasporto Passeggeri Emilia-Romagna provides vital connections across cities on different mainline networks, including Modena, Parma, Suzzara, Ferrara, Reggio Emilia and Bologna.

- Tuscany: La Ferroviaria Italiana operates in Arezzo province.

- Abruzzo: Sangritana runs daily services between Pescara and Lanciano.

In addition to these agencies, there's a great deal of other little operators, such as AMT Genova for the Genova-Casella railway.

Roads in Italy are an important mode of transport in Italy. The classification of the roads of Italy is regulated by the Italian traffic code, both from a technical and administrative point of view. The street nomenclature largely reflects the administrative classification. Italy's paved road network is well developed.

Italy is one of the countries with the most vehicles per capita, with 690 per 1000 people in 2010.[27][28] Italy has a total of 487,700 km (303,000 mi) of paved roads, of which 7,016 km (4,360 mi) are motorways with a general speed limit of 130 km/h (81 mph), which since 2009 was provisioned for extension up to 150 km/h (93 mph).[29] The speed limit in towns is usually 50 km/h (31 mph) and less commonly 30 km/h (19 mph).

Italy has 2,400 km (1,491 mi) of navigable waterways for various types of commercial traffic, although of limited overall value.[30]

In the northern regions of Lombardy and Veneto, commuter ferry boats operate on Lake Garda and Lake Como to connect towns and villages at both sides of the lakes. The waterways in Venice, including the Grand Canal, serve as the vital transportation network for local residents and tourists.

Frequent shuttle ferries (vaporetta) connect different points on the main island of Venice and other outlying islands of the lagoon. In addition, there are direct shuttle boats between Venice and the Venice Marco Polo Airport.

Italy has been the final destination of the Silk Road for many centuries. In particular, the construction of the Suez Canal intensified sea trade with East Africa and Asia from the 19th century. Since the end of the Cold War and increasing European integration, the trade relations, which were often interrupted in the 20th century, have intensified again. Because of its long seacoast, Italy also has many harbors for the transportation of both goods and passengers. In 2004 there were 43 major seaports including the Port of Genoa, the country's largest and the third busiest by cargo tonnage in the Mediterranean Sea.

Due to the increasing importance of the maritime Silk Road with its connections to Asia and East Africa, the Italian ports for Central and Eastern Europe have become important in recent years. In addition, the trade in goods is shifting from the European northern ports to the ports of the Mediterranean Sea due to the considerable time savings and environmental protection. In particular, the deep water port of Trieste in the northernmost part of the Mediterranean Sea is the target of Italian, Asian and European investments.[31][32]

| List of ports in Italy |

|---|

| Busiest ports by cargo tonnage in Italy (2008)[33] | Busiest ports by passengers in Italy (2008)[33] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Since October 2021, Italy's flag carrier airline is ITA Airways, which took over the brand, the IATA ticketing code, and many assets belonging to the former flag carrier Alitalia, after its bankruptcy.[34] ITA Airways serves 44 destinations (as of October 2021[update]) and also operates the former Alitalia regional subsidiary, Alitalia CityLiner.[35]

The country also has regional airlines (such as Air Dolomiti), low-cost carriers, and Charter and leisure carriers (including Neos, Blue Panorama Airlines and Poste Air Cargo). Major Italian cargo operators are ITA Airways Cargo and Cargolux Italia. In 2012 there were 130 airports in Italy, including the two hubs of Malpensa International Airport in Milan and Leonardo da Vinci International Airport in Rome.

Italy is the fifth in Europe by number of passengers by air transport, with about 148 million passengers or about 10% of the European total in 2011.[36] Most of passengers in Italy are on international flights (57%). A big share of domestic flights connect the major islands (Sardinia and Sicily) to the mainland.[36] Domestic flights between major Italian cities as Rome and Milan still play a relevant role but are declining since the opening of the Italian high-speed rail network in recent years.

Italy has a total as of 130 airports in 2012, of which 99 have paved runways:[30]

- over 3,047 m (9,997 ft): 9

- 2,438 to 3,047 m (7,999 to 9,997 ft): 31

- 1,524 to 2,437 m (5,000 to 7,995 ft): 18

- 914 to 1,523 m (2,999 to 4,997 ft): 29

- under 914 m (2,999 ft): 12

Airports - with unpaved runways in 2012:[30]

- total: 31

- 1,524 to 2,437 m (5,000 to 7,995 ft): 1

- 914 to 1,523 m (2,999 to 4,997 ft): 11

- under 914 m (2,999 ft): 19

Fossil fuel production

Like many other first world countries over the world who have the resources, Italy has been fairly focused on the future of renewables within their country. Italy has been a member of the International Energy Agency (IEA) since 1974, which is an organization that many countries who are dedicated to switching to renewable energy are a part of. Italy is ranked one of its lowest or high performing members within the organization when it comes to carbon intensity[37]. As mentioned from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) in 2019, Italy has no production whatsoever in the coal industry.

Italy is considered a significant oil refining center and is a crucial one in Europe[38]. In 2016 Italy exported around 0.6 million b/d and has an extensive crude oil pipeline called the Transalpine Pipeline running through the country that goes through Trieste which connects to Austria, the Czech Republic, and Germany[39].

Industrial emissions

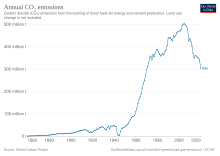

Italy's CO2 emissions reached 5.13 tonnes per capita in 2019, 17% higher than the world average (4.39 t/inhab).[40]

| 1971 | 1990 | 2018 | var. 2018/1971 |

var. 2018/1990 | |

| Emissions[41] (Mt CO2) | 289.4 | 389.4 | 317.1 | +9.6 % | -18.6 % |

| Emissions/capita[41] (t CO2) | 5.35 | 6.87 | 5.25 | -1.9 % | -23.6 % |

| Source : International Energy Agency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The International Energy Agency also provides the emissions for 2019: 302.8 MtCO2, down 4.5% compared to 2018h 1; per capita: 5.02 tCO2.[41]

Energy-related CO2 emissions in Italy experienced strong growth until 2005: 456.4 Mt, i.e. +58% in 34 years, then fell to 428.9 Mt in 2008, collapsed in 2009 due to the Great Recession: -10.5% and continued to decline thereafter.[41]

Per capita, Italy emitted 14.5% less than the European Union average (6.14 t/cap) in 2018.[41]

| Combustible | 1971 Mt CO2 |

1990 Mt CO2 |

2018 Mt CO2 |

% | var. 2018/1990 |

| Coal[41] | 32.6 | 56.6 | 34.3 | 11 % | -39.4 % |

| Oil[41] | 232.7 | 244.8 | 140.2 | 44 % | -42.7 % |

| Natural gas[41] | 24.1 | 87.1 | 137.6 | 43 % | +58 % |

| Source : International Energy Agency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 emissions | sector share | Emissions/capita | ||

| Sector | Million tons CO2 | % | tons CO2/hab. | |

| Energy sector excluding elect. | 18.1 | 6 % | 0.30 | |

| Industry and building | 71.3 | 22 % | 1.18 | |

| Transport | 103.6 | 33 % | 1.72 | |

| of which road transport | 94.9 | 30 % | 1.57 | |

| Residential | 67.0 | 21 % | 1.11 | |

| Tertiary | 47.7 | 15 % | 0.79 | |

| Total | 317.1 | 100 % | 5.25 | |

| Source : International Energy Agency[41] * after re-allocation of emissions from electricity and heat generation to consumption sectors. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Deforestation

Italy imports many wood products from other countries and was actually considered one of the worlds largest wood importers for fuel in 2009[42]. However Italy itself has no issues with deforestation but rather issues with a rise of uncontrolled forests. A study on The Italian forests in the last 150 years by Maruro Agnoletti, Francesco Piras, Martina Venturi and Antonio Santonio shows this large rate of forest growth over time starting in 1888 where Italy had an estimated 4.215.000 ha of forest cover compared to about 11.778.000 ha of forest cover that Italy has now as of January 2022. The issue isn’t necessarily the amount of forests Italy has but the lack of management. Over a long period of time with humans interacting with forests all over the world but specifically in Italy the natural forests are changed by the introduction of new plant and animal species which inevitably calls for management from humans to reduce the impact of these non native species[43].

Impacts on the natural environment

Temperature and weather changes

The global emissions of greenhouse gases have led to changes in the world's climate and temperatures that can be seen in Italy, impacting the environment around them.

Before the first signs of climate change and due to its geographical position, the Italian climate rarely experienced extreme events. It varied from region to region due to differences in latitude, relief and the influence of the sea. In fact, in the main part of Italy the climate is Mediterranean, with cold winters and snow in the mountains, while in the rest of the country the climate is subtropical, both humid and with high temperatures. (Climate of Italy)

However, since the first visible climate change, Italy is at the forefront of this change, with rising temperatures, melting glaciers, an increase in the number of extreme floods due to sea rise and high rainfall, and more frequent and prolonged periods of drought.

The Minister for the Environment, Sergio Costa, has even spoken of "tropicalisation", as Italy is facing an increase in extreme events with a higher frequency of violent events, seasonal shifts, short and intense rainfall, droughts and floods, and the rapid transition from cold to heat.

These climatic variations could be noticed in July 2021, when heavy rains were seen causing a lot of damage, while a month later the country experienced a record temperature, with a maximum temperature of 48.8 degrees, in Sicily putting 26 cities under red alert.[44]

These two phenomena reflect a changing climate in recent years, with an increase in extreme phenomena, which are more frequent, more sudden and more violent.

In addition to the increase in these extreme events, the changing Italian climate has seen a decrease in precipitation, such as the winter of 2022 which left Italy with 1⁄3 less rain. The average temperature, meanwhile, has increased, both in winter and summer.[45][46]

With the winter of 2022, recorded as the 5th warmest winter on the planet. This temperature increase is also measurable at the surface of the sea.

These changes are visible, at a regional level, as temperature changes in the Lazio region, where the capital, Rome, is located. This region is one of the warmest in Italy.

The Italian capital has not been spared from global warming, as the city's average temperature has risen between 1979 and 2022, from an annual average of 14.6°C in 1980 to an average of 16.3°C 40 years later. So it is getting hotter in the Rome area.

If we detail this increase a little more, and take the months of July and January between 1900 and 2018, the temperature has increased by 1.4°C for July and 1.2°C for January, and this increase is still rising.[47]

For the future, two scenarios have been developed for Italy based on the IPCC reports. Each scenario gives a probable climate variant resulting from the emission level chosen as a working hypothesis.

The first scenario (RCP4.5) envisages an increase in greenhouse gas emissions for several more decades, before stabilising and then decreasing before the end of the century. The RCP8.5 scenario models the most extreme case, with no regulation of greenhouse gas emissions.

The CMCC (Euro-Mediterranean Climate Change Centre Foundation) and the 2 scenarios seen above study the climate evolution between 2021 - 2100, based on a 1981 - 2010 reference. In Italy, we can see an increase in temperature, a decrease in the number of cold days, an increase in the number of consecutive days without rain and a decrease in summer rainfall for both scenarios. The number of days with winter precipitation increases in the north of the country while it decreases in the south.

A difference is noticeable for the scenario with no CO2 reduction (RCP8.5), which follows the same projections as the first scenario, but with much higher percentages of change.

Short term projections have been made from 2021 to 2050, we can see that the projections predict a global warming of temperatures, up to +2°C for southern Italy, in the months of June, July and August for the 8.5 scenario.[49]

Not only has the temperature and climate disruption been impacted by climate change, we can see that the sea level has also been modified.

Sea level rise

With the ongoing climate change, and thus the global increase in temperature, the polar ice caps and glaciers will continue to melt. Sea level rise is therefore expected and the Mediterranean coastline will be affected. According to the IPCC's CMIP6 model projection for the Mediterranean sea, under the SSP3-7.0 scenario, the sea level will rise by 0.6±0.3 m (spread P5-P95) by year 2100.[50] An alarming estimate was published by Strauss et al. in 2021.[51] Their prediction was a global 8.9 m sea level rise following a 4 °C warming by year 2300, which in turn would require the reallocation of the 8.9% of the Italian population in the affected regions, as of today.[51]

In 2007, the then active Italian Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea stated that plains and coastal areas of about 4500 km2 are at high risk of flooding in year 2100.[52] Their flood vulnerability assessment raised concern for the increased human activity along the coastlines, causing further erosion and damage to the environment. The anthropogenic stress in forms of industrial processes, growing urbanization and tourism, has reduced the coastal fringe resilience to sea level rise, as dunes have become fragmented or destroyed, or beaches narrowing to only a few meters or less. This could lead to consequences for human health and infrastructure in the case of flooding induced by sea level rise.[52][53]

Water resources

The expected sea level rise and risk of flooding along the Italian coastlines, constitutes a risk of groundwater contamination. The coastal fresh water beds might experience salt water intrusion of which may result in soil dryness in response to a lowered fresh water supply.[53]

The local effects of sea level rise in coastal regions have been studied in Murgia and Salento in southern Italy. These, as well as other regions, use groundwater as their primary supply of water for irrigation and drinking. The natural rate of refilling the groundwater aquifers by freshwater is too slow, making them sensitive to overexploitation (by e.g. illegal wells) as well as the seawater intrusions.[54] This has led to the observed salinity of up to 7 g/L in certain locations along Salento’s coast. As this salination proceeds, the groundwater discharge is expected to decrease significantly, in some cases resulting in a 16% reduction in water supply aimed for household use.[54]

Ecosystems

There are many ecosystems in Italy that are knowingly and unknowingly impacted by climate change as a result of human activity. A couple examples of affected ecosystems in Italy are the karst environments in southern Italy and coastal ecosystems affected by railways.

Karst landscapes are very sensitive ecosystems that consist of bedrock that is dissolving and is creating caves, sinkholes, streams, etc. Many different kinds of soluble types of rocks exist in karst landscapes, such as limestone and marble, resulting in water eroding and dissolving rocks away and creating the characteristic karst land formation[55]. Karst environments are so sensitive because of their close relationship with water and fragile rock. Anything that happens above will most likely affect the karst ecosystem below as well[56]. A paper on a study on karst environments in southern Italy called Evaluating the Human Disturbance to Karst Environments in Southern Italy by Fabiana Calò and Mario Parise focuses on southern-eastern Italy in the region of Apulia. The biggest threat to karst ecosystems in Apulia is stone clearing and quarrying, which completely changes the landscape of the karst environment and results in the collapse of cave systems[57]. The decline in karst environments in Italy (specifically in Apulia) is negative in the sense that it reduces not only biodiversity but karst environments also have the capacity to bind carbon dioxide within their underwater cave systems meaning Italy will lose this natural capability over time[58]. Karst environments also provide drinking water due to the filtrating abilities of the characteristic porous rocks of karst environments, leading to less drinking water for Italy as well[59]. Other actions by humans that can damage and degrade Karst environments can include mineral extraction, agriculture, cave tourism, runoff, pollution, decline of resources in water or animal species, deforestation, and so on[60].

There are many coasts in Italy bringing a lot of tourism and people to its ecosystems. Railways are often hailed as one of the better modes of transportation but even they can create a great impact on the surrounding nature. Railways demand flat and even land which is typically not the case by shorelines in Italy, so explosives have been used in the past to even out land for tracks. This is understandably quite impactful to the surrounding ecosystems. These railways near shorelines also suffer stability issues due to the constant erosion from the water nearby, so there is a constant need for protection from the shore with sea walls[61]. The constant need for reconstruction of sea walls with the use of mined resources and sediments from the shoreline has created an issue with coastal squeeze in areas of Italy[62]. Coastal squeeze is the degradation and eventual loss of ecosystems and habitats due to structures made by humans specifically on coasts where the natural process of "landward transgression" spurred on by the rise of the sea level is prevented[63]

Biodiversity

Due to anthropogenic reasons all over the world there has been a decline in ecosystem and environmental quality sometimes resulting in an alarming decrease in biodiversity. In Italy’s case biodiversity is threatened but not in the worst case scenario. Italy has around 67,500 different animal and plant species which makes up about 43% of all of Europe's species[64]. About 0.1% of Italy’s species are extinct, 2% are critically endangered, 3% endangered, and 5% vulnerable as of 2013. Loss of habitat, ecosystem fragmentation, and the degradation of the environment are all the biggest threats to biodiversity in Italy and throughout Europe. The habitats that are at greatest risk in Italy are wetlands, shrublands, rocky areas, and forests[65]. Urbanization is one of the biggest worries for biodiversity as it fragments and destroys ecosystems. Italy has been growing considerably and has been recently converting agricultural land to urban land. There was a law passed (Contenimento del consumo del suolo) in 2016 however that has the goal of decreasing the urbanization of land and attempting to get that conversion rate down to 0% by 2050[66].

Impacts on people

According to the IPCC and its latest reports climate change has been partly caused by humans but they are also the first to suffer the consequences.

In Italy, the effects are already being felt on the territory, where the government has not taken measures to deal with the magnitude of the situation. This has created numerous impacts on the economy, infrastructure, health and climate migration.

Economic impacts

The IPCC stressed that the cost of reducing emissions would be less than the cost of damage. However, at present, economic losses are already visible due to climate change in Italy. Infrastructure, tourism and the agricultural sector are the most affected by this economic loss.

In fact, a 15% drop in wine production has been noted for the year 2018, even though the country is the world's largest wine producer.[67]

Extreme phenomena such as floods and fires have caused colossal losses to agriculture, and have caused ¼ of the cultivable land to disappear in 25 years. In 2021, a loss of 25% of rice, 10% of wheat and 15% of fruit was recorded. This loss is estimated at nearly 14 billion euros in 2018 and forecasts for some regions a 25% drop in GDP (Gross Domestic Product) by 2080.[46]

Fires have an impact on crops, but also on the timber sector, increasing the trade deficit of the timber sector. The losses do not stop there, if we take into account the immediate costs of extinction and rehabilitation as well as the long-term costs of reconstruction, a fire would cost Italians about ten thousand euros per hectare.

Moreover, due to extreme events, Italian cities are increasingly threatened by floods and would cause damages, material and human, of about 1.6 billion euros per year by 2050.[46]

The economic impact of flooding in Italy can be seen in the 2019 state of emergency in Venice, where damage has been estimated at hundreds of millions of euros.

According to the European Environment Agency, the economic damage caused by extreme events between 1980-2020 has caused the loss of 90 billion euros to Italy, and reinforces the economic inequalities present in the country.

Moreover, future projections show that the costs of climate change impacts increase exponentially as temperatures rise in the different scenarios, with values ranging from 0.5% to 8% of GDP by the end of the century.[68]

Health impacts

Through the manifestation of mental health problems, illnesses due to climate change that disrupt food systems and increase infectious diseases and in the most extreme cases lead to death, human health is already being impacted by climate change.

Indeed, increases in temperature, ozone concentration or fine dust, particularly in urban areas, would increase deaths from ischaemic heart disease, stroke, nephropathy and metabolic disorders due to heat stress. This impact is most likely to affect vulnerable people such as the elderly, children, pregnant women and people with chronic diseases, and widens the inequality gap in health care.[70]

Rising temperatures and heat waves are one of the causes of death every year in Italy, which has prompted Italy to create the Heat Wave Forecasting and Warning System bulletins.

The Ministry of Health has set up Heat Wave Warning and Forecasting System (HHWWS) bulletins, if we take the example of the summer 2018 heatwave, 17 countries are in levels 2-3.[69]

Climate change has caused many impacts, and this can be shown through the Climate Risk Index 2020 ranking which reports events between 1999 and 2018. The studies rank the impacts of climate change in terms of economic losses, GDP losses and deaths.

In the ranking that records the highest number of deaths related to extreme weather events, Italy is the 6th country in the world and the first in Europe with almost 20,000 people dying due to floods and heat waves.[71]

Impacts on housing

Italian infrastructures are impacted by climate change and the effects are already visible.

Indeed, with territories where buildings, houses, roads and bridges are poorly or not maintained, material damage is present.

The most common causes of damage are floods such as the Acqua alta in 2019, which submerged the city of Venice under water, flooding homes and leaving them without electricity. Historical monuments were also impacted, such as St Mark's Basilica, which was flooded for the second time in less than a year and a half, whereas this had only happened four times in the last 1,200 years. These floods have made the ground and ground floors of Venice's homes too wet to live in.[72]

In 2021, near Lake Como in northern Italy, severe weather caused serious damage to nearby towns.

The rainfall caused the lake to overflow its banks, which in turn led to a great deal of damage, such as flooding, landslides and the transport of rocks, trees and even cars by the force of the muddy torrent, destroying everything in its path.[73]

According to a study, 91% of Italian municipalities are threatened by floods and landslides, with the consequences described above.

Impacts on migration

The impact of global warming has also caused people to migrate, as their environment has become unlivable. Decreased agricultural production, water scarcity and rising sea levels have forced people to move away from their homes, impacting the poorest people most rapidly.

For example Venice, which is one of the Italian cities most affected by the impacts of climate change, the city has seen its population decrease over the years. In 1966, the population was 121,000, while predictions for the end of 2022 show that the city may well fall below 50,000 inhabitants.[74]

Moreover, the city could be swallowed up, according to the people of Venice "it's not a question of if it will happen, it's just a question of when it will happen."

The Planpincieux glacier is also in the news, with 500,000 cubic meters of the glacier threatening to collapse due to the scorching temperatures hitting the Valle d'Aosta region in 2020, a year after a similar warning.

75 people had to be evacuated by the Italian civil protection, including dozens of residents.[75]

According to the authorities, ⅕ of the country is becoming desertified, and by 2100, 5,000 km2 will end up under water due to rising sea levels causing more and more climate migration.

This migration is spreading globally, and according to the World Bank, global warming could force 216 million people to migrate by 2050.[76]

Mitigation and adaptation

Policies and legislation

Italy is one of the 196 nations which have signed the Paris Agreement, of which constitutes climate change mitigation and adaptation actions. In 2020 the European Union members have updated their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), where each nation specifies their internal goals and policies to decrease their greenhouse gas emissions. Every two years the member states have to publish a progress report tracking their achievements. Within the union, the goal is to decrease the greenhouse gas emissions by 43% by 2030, compared to 2005. Italy specifically should decrease its emissions by 33% until 2030, and aim to be carbon-neutral by year 2050.[77]

Italy currently generates 11% of the European Union’s greenhouse gas emissions, but have had the most rapid decrease of the member countries since 2005.[78] All economic sectors decreased their contribution to the emissions, but with agriculture showing the smallest reduction. Italy has of year 2020 decreased its emissions by 13% compared to 2005.[78]

The Italian legislative framework for forestry was updated in 2018, which put in place new guidelines and arrangements to coordinate regional administrations, to establish a uniform national policy. The aim is to increase the ecosystem functions of forests as carbon sinks, and simultaneously obtain valuable timber products. The decree therefore emphasizes on sustainable forestry management. Beginning from recent decades, the instigated land-use changes in Italy is aimed to increase the current forested area covering about 31% of Italy’s terrestrial land area.[78]

Approaches

To mitigate climate change, Italy has focused on the implementation of renewables and improved energy efficiencies. Subsequently, coal as an energy source is set to be phased out by year 2025.[79]

Between 2005 and 2019, the energy industry reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by 42%, making it the third largest share of Italy’s total emissions. This decrease arise in part by the increased utilization of renewable energy sources (RES), which increased to 18% 2019. This share should increase to 30% by 2030, with emphasis on wind and solar power. Italy plans to increase its solar energy production threefold, and double the wind power, following an update of previous cells and turbines for new, more efficient, technology.[78] Renewable energy sources are aimed supply 55% of the total electricity consumption in Italy year 2030, corresponding to 187 TWh out of 340 TWh.[79] To achieve this, the solar power capacity has to increase from 19 to 52 GW, and wind power from 10 to 19 GW.[79]

The renewable energy source usage within transportation is further set to reach 22% by 2030.[78] Moreover, the Italian government has put in action subsidies and regulations for both public and private sector to renew their transport fleet. The goal is to reach 4 million electric and 2 million hybrid cars by 2030, as well as increased usage of advanced biofuels such as biomethane due to Italy’s already extensive gas infrastructure.[78]

According to Italy's national recovery and resilience plan[80], about 62 billion Euros are earmarked for projects in development of the infrastructure such as improved railroad networks and other public transport, as well as an overall digitalization of society and low-emission housing.

Society and culture

Activism

Public perception of climate change

Private sector efforts

Controversies

Arts and media

See also

References

External links

- ^ "'Historic' vote means Italian state must now protect animals and ecosystems". euronews.green.

- ^ "Traité entre la République française et la République italienne pour une coopération bilatérale renforcée". elysee.

- ^ "IEA Key energy statistics 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ data from Terna - Italian electric grid

- ^ a b c "Il rapporto Comuni Rinnovabili 2015". Comuni Rinnovabili (in Italian). Legambiente. 18 May 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ "The spotlight sharpens: Eni and corruption in Republic of Congo's oil sector". Global Witness.

- ^ "Storia di Milano – La Centrale elettrica di via Santa Radegonda" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ "Summary for Eni SpA". Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "In Val d'Agri with Upstream activities". Eni. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Trivellazioni in Adriatico ferme ma il gas italiano costa un decimo" (in Italian). 6 November 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Inventario delle risorse geotermiche nazionali". UNMIG. 2011. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "TERNA statistics data". Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ "The Italian Montalto di Castro and Rovigo PV plants". www.solarserver.com. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Rapporto Statistico sugli Impianti a fonti rinnovabili". Gestore dei Servizi Energetici. 19 December 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Nuclear Production". Enel. 31 December 2013. Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Emerging Nuclear Energy Countries". World Nuclear Association. December 2014. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Frecciarossa 1000 in Figures". Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ "Frecciarossa 1000 Very High-Speed Train". Railway Technology. Archived from the original on 9 August 2015. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- ^ "French Train Breaks Speed Record". CBC News. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ Compare List of countries by rail transport network size.

- ^ "La rete oggi". RFI Rete Ferroviaria Italiana. Archived from the original on 4 December 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ^ "The age of the train" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "Rail Passes - ItaliaRail - Italy Train Ticket and Rail Pass Experts". italiarail.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ "Due record in prova per il Frecciarossa" (in Italian). Repubblica. 2009-02-04. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ "Viaggia con i treni Frecciarossa e acquista il biglietti a prezzi scontati - Le Frecce - Trenitalia". trenitalia.com (in Italian). Archived from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ^ "Treno ad alta velocità Le Frecce" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ John Sousanis (15 August 2011). "World Vehicle Population Tops 1 Billion Units". Ward AutoWorld. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ^ See also: List of countries by vehicles per capita

- ^ Art. 142 Traffic Regulation

- ^ a b c "Italy". The World Factbook. CIA. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ Marcus Hernig: Die Renaissance der Seidenstraße (2018) pp 112.

- ^ Bernhard Simon: Can The New Silk Road Compete With The Maritime Silk Road? in The Maritime Executive, 1 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Graduatoria dei porti italiani". Istat. Retrieved 9 January 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Buckley, Julia (18 October 2021). "Italy reveals its new national airline". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ Villamizar, Helwing (15 October 2021). "Italian Flag Carrier ITA Airways Is Born". Airways Magazine. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Trasporto aereo in Italia (PDF)". ISTAT. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "Italy - Countries & Regions". IEA. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ "International - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ "International - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ "Key World Energy Statistics 2021" (PDF). pp. 60–69. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion 2020 : Highlights". Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/files/eventi/degrado-foreste-english.pdf

- ^ Agnoletti, Mauro; Piras, Francesco; Venturi, Martina; Santoro, Antonio (2022-01-01). "Cultural values and forest dynamics: The Italian forests in the last 150 years". Forest Ecology and Management. 503: 119655. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119655. ISSN 0378-1127.

{{cite journal}}: no-break space character in|title=at position 73 (help) - ^ "Réchauffement climatique : record européen de chaleur battu en Italie". maxisciences.

- ^ "Giornata Acqua: il Po a secco come ad agosto, sos siccità". Coldiretti.

- ^ a b c "Clima: inverno pazzo con +0,55 gradi e piogge dimezzate". coldiretti.

- ^ a b "Previsioni Meteorologiche per ROMA (RM)". meteo aeronautica.

- ^ "analisi de rischio, cambiamenti climatici in Italia" (PDF). cmcc.

- ^ "Scenari climatici per l'Italia". cmcc.

- ^ Iturbide, M., Fernández, J., Gutiérrez, J.M., Bedia, J., Cimadevilla, E., Díez-Sierra, J., Manzanas, R., Casanueva, A., Baño-Medina, J., Milovac, J., Herrera, S., Cofiño, A.S., San Martín, D., García-Díez, M., Hauser, M., Huard, D., Yelekci, Ö. (2021) Repository supporting the implementation of FAIR principles in the IPCC-WG1 Atlas. Zenodo, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3691645. Available from: https://github.com/IPCC-WG1/Atlas

- ^ a b Strauss, Benjamin H; Kulp, Scott A; Rasmussen, D J; Levermann, Anders (2021-10-22). "Unprecedented threats to cities from multi-century sea level rise". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (11): 114015. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2e6b. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ^ a b Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea. Fourth National Communication under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2007. Available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/itanc4.pdf

- ^ a b Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea. Fifth National Communication under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2009. Available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/ita_nc5.pdf

- ^ a b Masciopinto, Costantino; Liso, Isabella Serena (2016-11-01). "Assessment of the impact of sea-level rise due to climate change on coastal groundwater discharge". Science of The Total Environment. 569–570: 672–680. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.183. ISSN 0048-9697.

- ^ "Karst Landscapes - Caves and Karst (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ Calò, Fabiana; Parise, Mario (2006-12-01). "Evaluating the Human Disturbance to Karst Environments in Southern Italy". Acta Carsologica. 35 (2–3). doi:10.3986/ac.v35i2-3.227. ISSN 1580-2612.

- ^ Calò, Fabiana; Parise, Mario (2006-12-01). "Evaluating the Human Disturbance to Karst Environments in Southern Italy". Acta Carsologica. 35 (2–3). doi:10.3986/ac.v35i2-3.227. ISSN 1580-2612.

- ^ "Why We Should Protect Karst Landscapes | Heinrich Böll Foundation | Southeast Asia Regional Office". Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ "Why We Should Protect Karst Landscapes | Heinrich Böll Foundation | Southeast Asia Regional Office". Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ Calò, Fabiana; Parise, Mario (2006-12-01). "Evaluating the Human Disturbance to Karst Environments in Southern Italy". Acta Carsologica. 35 (2–3). doi:10.3986/ac.v35i2-3.227. ISSN 1580-2612.

- ^ Cinelli, Irene; Anfuso, Giorgio; Privitera, Sandro; Pranzini, Enzo (2021-01). "An Overview on Railway Impacts on Coastal Environment and Beach Tourism in Sicily (Italy)". Sustainability. 13 (13): 7068. doi:10.3390/su13137068. ISSN 2071-1050.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Cinelli, Irene; Anfuso, Giorgio; Privitera, Sandro; Pranzini, Enzo (2021-01). "An Overview on Railway Impacts on Coastal Environment and Beach Tourism in Sicily (Italy)". Sustainability. 13 (13): 7068. doi:10.3390/su13137068. ISSN 2071-1050.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "What is coastal squeeze?". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ^ https://www.iucn.org/sites/dev/files/content/documents/italy_s_biodiversity_at_risk_fact_sheet_may_2013.pdf

- ^ https://www.iucn.org/sites/dev/files/content/documents/italy_s_biodiversity_at_risk_fact_sheet_may_2013.pdf

- ^ Ivardiganapini, Cecilia (2020-06-19). "Land Being Lost to Urbanization: A Threat to Biodiversity in Italy". Climate Scorecard. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ^ "country statistics". OIV (International Organisation of Vine and Wine).

- ^ "Economic losses from climate-related extremes in Europe". european environment agency.

- ^ a b "Ondata di calore estesa in tutta Italia". Ministero della Salute.

- ^ "Climate change 2014, impacts, adaptation and vulnerability" (PDF). IPCC.

- ^ "GLOBAL CLIMATE RISK INDEX 2020" (PDF). Germanwatch.

- ^ "ACQUA ALTA ET RÉCHAUFFEMENT CLIMATIQUE: VENISE EST-ELLE EN DANGER DE DISPARITION?". BFMTV.

- ^ "Des pluies diluviennes provoquent d'importants dégâts autour du lac de Côme en Italie". Parismatch.

- ^ "Population decline set to turn Venice into Italy's Disneyland". The Guardian.

- ^ "Réchauffement climatique: en Italie, le glacier Planpincieux menace d'effondrement". rfi.

- ^ "Climate Change Could Force 216 Million People to Migrate Within Their Own Countries by 2050". World Bank.

- ^ Submission by Germany and the European Commission on behalf of the European Union and its member states. Update of the NDC of the European Union and its Member States. 2020. Available at: https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/ndcstaging/PublishedDocuments/Italy%20First/EU_NDC_Submission_December%202020.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f European Parliamentary Research Service. Climate action in Italy: Latest state of play. 2021. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/690663/EPRS_BRI(2021)690663_EN.pdf

- ^ a b c Massimo Lombardini. Italy’s Energy and Climate Policies in the Post COVID-19 Recovery. 2021. Available at: https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/memo_lombardini_italy_necp_in_an_european_context_fev_2021.pdf

- ^ Italia Domani. Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza. 2021. Available at: https://www.governo.it/sites/governo.it/files/PNRR.pdf