Pre-dreadnought battleship

The term pre-dreadnought refers to the kind of battleship built in the closing years of the 19th Century and the first years of the 20th century, and which was made obsolete by the launching of HMS Dreadnought in 1906.

The 'pre-dreadnought' period saw rapid growth in naval construction, and also a close consensus between naval powers about what kind of battleship to build. The pre-dreadnought can be seen as the last ironclad warship or as the first modern battleships. The technical hallmarks of the pre-dreadnought — steel construction and armour, triple-expansion steam engines, and a mixed armament including high-calibre breech-loading guns mounted in turrets — had already been developed in ironclad warships.

The major naval clashes of the pre-dreadnought era occurred in the Sino-Japanese war of 1894–5 and the Russo-Japanese war of 1904–5. The development of the dreadnought made all pre-dreadnoughts obsolescent, as the new ships combined improved range, speed and firepower. Nevertheless pre-dreadnoughts played an important role as 'expendable' battleships in World War I, and some survived to see action in World War II.

Evolution from the Ironclad

While the end of the pre-dreadnought era is clearly demarcated by the Dreadnought herself, just when the era begins, and thus which ships represent the first pre-dreadnoughts, is open to debate.

The pre-dreadnought developed from a long, international lineage of turreted ironclad warships. Ships as early as HMS Devastation of 1871 were built without masts and armed with four heavy guns mounted in two turrets fore and aft, giving them an appearance similar to that of the pre-dreadnought. Devastation was a breastwork monitor, built to attack enemy coasts and harbours; because of her very low freeboard, she would have found it impossible to fight on the high seas. [1]. The Royal Navy, and other navies worldwide, continued to build masted ships with a quite different layout as their high-seas battlefleet until the 1880s.

The distinction between coast-assault battleship and cruising battleship became blurred with the Admiral class ordered in 1880. These ships reflected developments in ironclad design, being protected by compound armour rather than wrought iron. Equipped with breech-loading guns of between 12 inch and 16.25 inch calibre, they continued the trend of ironclad warships towards gigantic weapons. The guns were mounted in open barbettes to save weight. Some historians see these ships as essentially pre-dreadnoughts; others view them as a confused an unsuccessful design which shared the weakness of the Devastation as a high-seas battleship while also being fatally weak for a coast assault role. [2][3] [4]

Another potential dividing line is the Royal Sovereign class of 1889. They retained barbettes but were uniformly armed with 13.5 in guns; they were also significantly larger (at 14,000 tons displacement) and faster (thanks to triple-expansion steam engines) than the Admirals. Just as importantly the Royal Sovereigns had a higher freeboard, making them unequivocally capable of the high-seas battleship role.[5][6]

The last ships which can be considered the 'first pre-dreadnoughts' are the Majestic class, of which the first ship was launched in 1895. These ships were built and armoured entirely of steel, and their guns were mounted in fully-enclosed barbettes, inevitably referred to as turrets. They also adopted a 12 in main gun, which due to advances in casting and propellant was lighter and more powerful than the previous guns of larger calibre.[7].[8]

Armament

Pre-dreadnoughts had a 'mixed' armament scheme, carrying several different calibres of guns for different roles in ship-to-ship combat.

The main armament of a pre-dreadnought was with few exceptions four heavy guns, mounted in two centreline turrets fore and aft. These guns were slow-firing and, initially, of limited accuracy; however they were the only guns heavy enough to penetrate the thick armour which protected the engines, magazines and main guns of enemy battleships.[9]

The most common calibre for the main armament was 12 inches (305 mm); British battleships from the Majestic class onwards carried this calibre, as did French ships from the Charlemagne class (laid down 1894). Japan, importing most of its guns from Britain, used 12-inch guns. The United States used alternatively 12-inch and 13-inch guns for most of the 1890s until the Maine class, laid down 1899, after which the 12-inch gun was universal. Russia used either 12-inch or 10-inch main armament. The first German pre-dreadnoughts used a 9.4-inch gun, but ships laid down after 1900, starting with the Braunschweig class tended to carry 11-inch guns.[10]

Pre-dreadnoughts also carried a 'secondary' battery. This consisted of smaller guns, typically 6-inch, though any calibre from 4 in to 9.2 in could be used. Virtually all secondary guns were 'quick firing', employing a number of innovations to increase the rate of fire; the propellant was provided in a brass cartridge, and both the breech mechanism and the mounting were suitable for rapid aiming and reloading.[11]

The role of the secondary battery was to damage the less well-armoured parts of an enemy battleship; while unable to penetrate the main armour belt, it might score hits on lightly armoured areas like the bridge, or start fires. Equally important, the secondary armament was to be used against enemy cruisers, destroyers and even torpedo boats. A medium-calibre gun could expect to penetrate the light armour of smaller ships, while the rate of fire of the secondary battery was important in scoring a hit against a small, maneuverable target.

Secondary guns were mounted in a variety of methods; sometimes carried in turrets, they were just as often positioned in fixed armoured casemates in the side of the hull, or in unarmoured positions on upper decks.

Some pre-dreadnoughts carried an 'intermediate' battery, typically of 8-inch to 10-inch calibre. The intermediate battery was a method of packing more heavy firepower into the same battleship, principally of use against battleships or at long ranges. By the end of the pre-dreadnought period, it became common for battleships to carry a secondary armament entirely of these calibres.

During the ironclad age, the range of engagements increased; in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–5 battles were fought at around 2,000 metres, while in the Battle of the Yellow Sea in 1904, engagements took place at as long a range as 7,000m.[12] In part, the increase in engagement range was due to the longer range of torpedoes, and in part due to improved gunnery and fire-control. The consequence for shipbuilding was a trend towards heavier secondary armament, of the same calibre that the 'intermediate' battery had been previously; the Royal Navy's last pre-dreadnought class, the Lord Nelson class, carried ten 9.2-inch guns as her secondary armament. Ships with a uniform, heavy secondary battery are often referred ro as 'semi-dreadnought's.[13]

The pre-dreadnought's armament was completed by a tertiary battery of light, rapid-fire guns. These could be of any calibre from 3-inch down to machine guns. Their role was to give short-range protection against torpedo boats, or to rake the deck and superstructure of a battleship.[14]

In addition to their gun armament, many pre-dreadnought battleships were armed with torpedos, fired from fixed tubes located either above or below the waterline.

Protection

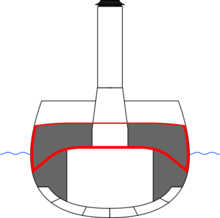

Pre-dreadnought battleships carried a considerable weight of steel armour. Experience showed that, rather than giving the ship uniform armour protection, it was best to concentrate armour over critical areas. The central section of the hull, which housed the boilers and engines, was protected by the main belt, which ran from just below the waterline to some distance above it. This 'central citadel' was intended to protect the engines from even the most powerful shells. The main armament and the magazines were protected by projections of thick armour from the main belt. The beginning of the pre-dreadnought era was marked by a move from mounting the main armament in open barbettes to an all-enclosed, turret mounting.[15]

The main belt armour would normally taper to a lesser thickness along the side of the hull some distance towards bow and stern, and perhaps further up from the central citadel towards the superstructure. The deck was typically lightly armoured with perhaps 2 in or 3 in of steel; the role of the deck was to protect against high-angle, long-range 'plunging fire'.

Early pre-dreadnoughts, for instance the Royal Sovereign class were armored with compound armor. This was soon replaced with more effective all-steel armor made using the Harvey process. During the late 1890s, this was replaced by Krupp armour in the last pre-dreadnought battleships. Because of the rapidly changing armor technology of the era, the type of armor has a large effect on the effectiveness of a ship's protection. Twelve inches of compound armor provided the same protection as just 7.5 inches of Harvey or 5.75 inches of Krupp.[16]

Propulsion

All pre-dreadnoughts were powered by reciprocating steam engines. Most were capable of top speeds between 16 and 18 knots. The earliest vessels used compound engines, but these were soon replaced with more efficient triple expansion engines.[16] Most pre-dreadnought battleships used twin propellors, though the French and German navies favored triple-screw arrangements.[8] Coal fired boilers were used aboard all pre-dreadnought battleships as built. Towards the end some navies began using oil to supplement, rather than replace, coal fired boilers.[8]

Pre-dreadnought fleets and battles

While pre-dreadnoughts served all around the globe, the only battles of pre-dreadnought fleets occurred in the Far East and the Carribean. The pre-dreadnought age saw the beginning of the end of the 19th-century naval balance of power in which France and Russia vied for competition against the massive British Royal Navy, and saw the start of the rise of the 'new naval powers' of Germany, Japan and the USA. The new ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy and to a lesser extent the U.S. Navy supported those powers' colonial expansion.

Europe

While Europe remained at peace, it was here that the greatest number of pre-dreadnought battleships were constructed.

The British Royal Navy remained the world's largest fleet. In 1889, Britain formally adopted a 'Two Power Standard' committing her to building enough battleships to exceed the two largest other navies combined; at the time, this meant France and Russia, who became formally allied in the early 1890s.[17]. The Royal Sovereign class and Majestic class referred to above were followed by a regular programme of construction at a much quicker pace than in previous years. The Canopus, Formidable, Duncan and King Edward VII classes appeared in rapid succession from 1897 to 1905.[18]. Counting two ships ordered by Chile but taken over by the British, the Royal Navy had 39 pre-dreadnought battleships ready or building by 1904, starting the count from the Majestics. Over two dozen older battleships remained in service. The last British pre-dreadnoughts, the Lord Nelson class, appeared after Dreadnought herself.

France, Britain's traditional naval rival, had paused her battleship building during the 1880s because of the influence of the Jeune Ecole doctrine, which favoured torpedo boats to battleships. The first French battleship after the lacuna of the 1880s was Brennus, laid down 1889. Brennus and the ships which followed her were individual, as opposed to the large classes of British ships; they also carried an idiosyncratic arrangement of heavy guns, with Brennus carrying three 13.4-inch guns and the ships which followed carrying two 12-inch and two 10.8-inch in single turrets. The Charlemagne class, laid down 1894-6, were the first to adopt the standard four 12-inch gun heavy armament.[19] The Jeune Ecole retained a strong influence on French naval strategy, and by the end of the 19th Century France had abandoned competition with Britain in battleships numbers.[20]. The French suffered the most from the Dreadnought revolution, with four ships of the Liberte class still building when Dreadnought launched, and a further six of the Danton class begun afterwards.

Pre-dreadnought battleships saw service during the Spanish-American War including the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, as well as during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, notably at the Battle of Tsushima.

Obsolescence

In 1906, the commissioning of HMS Dreadnought brought the obsolescence of all existing battleships. Dreadnought, by scrapping the secondary battery, was able to carry ten 12-inch guns rather than four. She could fire eight heavy guns broadside, as opposed to two from a pre-dreadnought; and six guns ahead, as opposed to two. The move to an 'all-big-gun' design was a logical conclusion of the increasingly long engagement ranges and heavier secondary batteries of the last pre-dreadnoughts; Japan and the USA had designed ships with a similar armament.

Dreadnought's further innovation was the use of steam turbines for propulsion, giving her and future battleships an advantage in speed as well as firepower. The combination gave Dreadnought and the subsequent classes of dreadnought battleships a decisive advantage over earlier battleships.

Nevertheless, pre-dreadnoughts continued in active service and saw significant combat use even when obsolete.

World War I

During World War I the remaining pre-dreadnoughts were generally used for second-line tasks such as convoy escort and shore bombardment (notably during the Gallipoli campaign where a number were lost to submarine attack), although a small squadron of German ones were present at the Battle of Jutland in 1916 (German sailors called them the "five minute ships", which was the amount of time they were expected to survive).

World War II

After World War One most pre-dreadnoughts were broken up along with many dreadnoughts. Germany was allowed to keep eight in service for coastal defense duties under the terms of the Versailles treaty and two of these soldiered on into World War II. One of them, Schleswig-Holstein, shelled the Polish Westerplatte peninsula from the first minutes of the war. Greece also had a pair of ex-US Navy pre-dreadnoughts in service at the time; they were sunk in due course when Germany invaded her in 1941.

Today

The only pre-dreadnought preserved today is the Japanese Navy's flagship at the Battle of Tsushima, the Mikasa, which is now located in Yokosuka, where it has been a museum ship since 1925.

External links

- Pre-Dreadnought Preservation

- US Pre-Dreadnoughts

- Pre-Dreadnoughts in WWII

- British and German Pre-Dreadnoughts

References

- ^ Beeler, p.93-5

- ^ Beeler, p. 167-8

- ^ Beeler, John (2001). Birth of the Battleship: British Capital Ship Design 1870-1881. Anapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-213-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Burt, R.A. (1988). British Battleships 1889-1904. Anapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-061-0.

- ^ Beeler, p.168

- ^ Gardiner, p.116

- ^ Gardiner, p.117

- ^ a b c Robert Gardiner ed., ed. (1992). Steam, Steel & Shellfire: The Steam Warship 1815-1905. Conway's History of the Ship. Anapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-774-0.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) Cite error: The named reference "SteamSteel&Shellfire" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Sumrall, R The Battleship and Battlecruiser in Gardiner & Brown (eds) Eclipse of the Big Gun. p.14

- ^ Roberts, The Pre-Dreadnought Age in Gardiner (ed) Steam Steel and Shellfire; p.117-125

- ^ Campbell, J Naval Armaments and Armour in Gardiner (ed) Steam, Steel and Shellfire p.163

- ^ Sondhaus, Lawrence Naval Warfare 1815–1914, p.170, 171, 189

- ^ Roberts, The Pre-Dreadnought Age p.125–6

- ^ Sumrall, p.14

- ^ Roberts, The Pre-Dreadnought Age, p.117

- ^ a b X

- ^ Sondhaus, p.161

- ^ Sondhaus, p.168, 182

- ^ Sondhaus, p.167

- ^ Sondhaus, p.181