Push–pull train

Push-pull is a mode of operation for locomotive-hauled trains allowing them to be driven from either end. A push-pull train has a locomotive at one end of the train, connected via multiple-unit train control, to a vehicle equipped with a second control cab at the rear of the train. In the UK the control vehicle is referred to as a Driving Trailer or Driving Van Trailer (DVT), while in the USA they are called cab cars. Alternatively, the train may have a locomotive at each end.

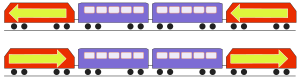

Train formation

Locomotive at one end

| Multiple unit trains |

|---|

| Subtypes |

| Technology |

| By country |

Historically push-pull trains with steam power provided the driver with basic controls at the cab end along with a bell or other signalling code system to communicate with the fireman located in the engine itself in order to pass commands to adjust controls not available in the cab.

At low speeds some push-pull trains are run entirely from the engine with the guard operating bell codes and brakes from the leading cab when the locomotive is pushing the train.

Many mountain railways also operate on similar principles in order to keep the locomotive lower down than the carriage so that there is no opportunity for a carriage to run away from a train down the gradient, and also so that if the locomotive ever did run away it would not take the carriage with it.

Modern train control systems use sophisticated electronics to allow full remote control of locomotives. Nevertheless push-pull operation still requires considerable design care to ensure that control system failure does not endanger passengers and also to ensure that in the event of a derailment the pushing locomotive does not push a derailed train into an obstacle worsening the accident. The 1984 Polmont rail crash (in Scotland) occurred when a push-pull train struck a cow on the track. Push-pull operation has also been blamed for worsening a number of derailments by trains of the Metrolink commuter rail service in greater Los Angeles.

When operating push-pull the train can be driven from either the locomotive or the alternate cab. If the train is heading in the direction in which the locomotive end of the train is facing, this is considered 'pulling'. If the train is heading in the opposite direction, this is considered 'pushing', and the motorman or engineer is located in the alternate cab. This configuration means that the locomotive never needs to be uncoupled from the train, and ensures fast turnaround times at a railway station terminus.

Locomotive in the middle

In certain situations the locomotive is placed in the middle of the train rather than at one end but driven from cabs at the train ends. The GWR sometimes did this when multiple autocoaches were linked up in an autotrain, as the mechanical linkages used to control the steam locomotive were not capable of reliable operation through more than two interconnections. When the locomotive is placed mid-train, both directions are considered 'push'.

Two locomotives

Alternatively, a push-pull train, especially a long one, may have a locomotive on both ends so that there is always one locomotive pushing and one locomotive pulling. In this case caution must be used to make sure that the two locomotives do not put too much stress on the cars from uneven locomotives. This two-locomotive formation is used by the InterCity 125 (and its Australian equivalent, the XPT). It is usual to arrange things so that the trailing locomotive supplies less power and that the locomotive at the front does more pulling than the locomotive at the rear does pushing. Having an independent locomotive as opposed to a power car at each end is also known in the railway world as a top and tail. When this configuration is used in the US, only one locomotive is allowed to provide head end power (HEP: electricity supply for heating, lighting, etc) to the train.

Distributed power

In this configuration locomotives hauling a train are located other than at the front or back. It may include remote control locomotives in the middle of a train. Where operational considerations or economics require it, trains can be made longer if intermediate locomotives are inserted in the train and remotely controlled from the leading locomotive.

History

Britain

The first company to use the system was the Great Western Railway, which in 1904 equipped carriages and 0-6-0 locomotives as an "autotrain" to run on the Brentford Branch Line (between Southall and Brentford) as an experimental substitute for steam railcars. Control was by rodding and the mechanism allowed the driving compartment to be either one or two carriages -distant from the engine. With the engine in the middle of a formation, up to four carriages could be used. To reduce the surprise of a locomotive at the "wrong" end of its train, some were initially fitted with panelling painted in carriage livery.[1] The experiment was successful and the company's remaining railcars were gradually converted for autotrain use and purpose-built units constructed. Other companies followed the lead in 1905: the North Eastern and LBSCR using a compressed-air method of control and the Midland, using a cable-and-pulley mechanism. The Great Central deployed the trains in 1906, using cable controls similar to that of the Midland. By the 1920s most companies had them and they remained in use until replaced by diesel multiple units (DMUs) in the 1950s.[1]

In 1967 the Southern Region, already familiar with operating electric multiple units, applied the technique to its services from London Waterloo station to Bournemouth, which were operated by electro-diesel locomotives.[1]

In the early 1980s the Scottish Region trialled a system using a Class 27 locomotive at each end of a rake of coaches that had been specially retro-fitted with the necessary 'Blue Star' multiple working cables to control the remote unit; but some problems of delay in actuation were experienced. They were replaced by a system whereby a Driving Brake Standard Open (DBSO) could control the Class 47/7 locomotive via computerised time-division multiplex (TDM) signalling through the train lighting circuits. This had the added benefit that intermediate carriages needed no special equipment, and was found more satisfactory. Such trains became widely used on the intensive passenger service between Edinburgh Waverley and Glasgow Queen Street.[1][2]

In 1988, Mark 3 Driving Van Trailers (DVT) were built for the extended electrification of the West Coast Main Line and the Mark 4 DVT was built as part of the Electra project for the East Coast Main Line. The Mark 4 DVT can be retro-fitted to tilt.

More recently, some of these DVTs have been modified to operate with Class 67 locomotives for the Wrexham, Shropshire, Marylebone Railway Company.

Ireland

Iarnród Éireann employs push-pull trains of three different kinds. The first of these were built in 1989 and are based on the British Rail Mark 3 design, with a non-gangwayed driving cab fitted. These are operated with 201 Class locomotives, although in the past 121 Class locomotives were also used. It was not unknown for these sets to be hauled as normal coaching stock by non-push-pull fitted locomotives. The sets originally operated in the Dublin outer-suburban area and on the Limerick–Limerick Junction shuttle, but were gradually moved to mainline Intercity routes out of Heuston after the introduction of railcar sets elsewhere.

Also in operation on the IÉ newtork are De Dietrich Ferroviaire -built "Enterprise" push-pull sets, jointly owned with Northern Ireland Railways for operation on the Dublin to Belfast route. These are powered by 201 Class locos.

The other type of push-pull train used in Ireland is the Mark 4 type (not to be confused with the British Rail Mark 4 type). These sets, delivered in 2005–06, are used exclusively on the Dublin to Cork route, again operated by 201 Class locos.

New Zealand

The Auckland suburban network run by Veolia uses DC Class locomotives owned by now KiwiRail, operating in push-pull mode with sets of normally 3 SA cars and an SD driving car (all ex British Rail Mark 2 carriages rebuilt for suburban service on 1067 gauge lines) owned by the Auckland Regional Transport Authority (ARTA).

See also

Notes

Further reading

- King, Mike (2006). An Illustrated History of Southern Push-Pull Stock. Ian Allan Publishing (OPC). p. 160 pages. ISBN 0860935965.

- Lewis, John (1991). Great Western Railway Auto Trailers: Pre-grouping Vehicles (Part 1). Wild Swan. p. 208 pages. ISBN 0 906867 99 1.

- Lewis, John (1995). Great Western Railway Auto Trailers: Post-Grouping and Absorbed Vehicles (Part 2). Wild Swan Publications Ltd. p. 184 pages. ISBN 1 874103 25 9.

- Lewis, John (2004). Great Western Steam Railmotors: and their services. Wild Swan Publications Ltd. ISBN 1 874103 96 8.