History of Cologne

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (September 2012) |

The History of Cologne, Germany's oldest major city, can be broken into several periods.

Roman period

| This article is part of a series on the |

| City of Cologne |

|---|

|

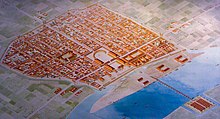

In 39 BC, the tribe of the Ubii entered into an agreement with the Roman forces and settled on the left bank of the Rhine. Their headquarters was Oppidum Ubiorum — the settlement of the Ubii, and at the same time an important Roman military base. In 50 AD, Agrippina the Younger, wife of the Emperor Claudius, who was born in Cologne, asked for her home village to be raised to the status of a colonia — a city under Roman law. It was called Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensis (a "colony of Claudius and the altar of Agrippina"), or Colonia Agrippina, "the Colony of Agrippina". In 80 AD the Eifel Aqueduct was built as a major source for water. The Eifel Aqeduct was one of the longest aqueducts of the Roman Empire, it delivered 20,000 cubic metres of water to the city every day. Ten years later, the colonia became the capital of the Roman province of Lower Germany Germania Inferior with a total population of 45,000 people.

In 260 AD Postumus made Cologne the capital of the Gallic Empire which included the German and Gallic provinces, Britannia and the provinces of Hispania. The Gallic Empire lasted only fourteen years.

By the 3rd century, only 20,000 people lived in and around the town. In 310 AD, Emperor Constantine I had a bridge over the Rhine constructed; this was guarded by the castellum Divitia (nowadays "Deutz").

In 321 AD Jews are documented in Cologne. When exactly the first Jews arrived in the Rhineland area cannot be established, though the Cologne community claims to be the oldest north of the Alps.

Frank, Merovingian, and Carolingian periods

Colonia was pillaged several times by the Franks in the 4th century and the city finally fell to the Ripuarian Franks in 459 AD. Two lavish burial sites located near the Cathedral date from this time of late antiquity.

In 355 AD, the Alemanni tribes besieged the town for 10 months. At the time, the garrison of Colonia Agrippina was under the generalship of Marcus Vitellus. The city was captured after the months of siege and was reestablished as a Roman colonia several months afterwards by the soon-to-be Roman Emperor Julian. In 455, the Salian Franks finally captured Cologne and made it their capital city. In 795 the chaplain to Charlemagne, Hildebold was elevated to Archbishop of Cologne, a newly created archbishopric.

Prince-Archbishops and Electors of Cologne

Cologne's first Christian bishop was Maternus. He was responsible for the construction of the first cathedral, a square building erected early in the 4th century. In 794, Hildebald (or Hildebold) was the first Bishop of Cologne to be elevated to Archbishop of Cologne. Bruno I (925-965), younger brother of Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, founded several monasteries here. Subsequent Archbishops of Cologne became very influential as advisers to the Saxon, Salian and Hohenstaufen dynasties. From 1031, they also held the office of Arch-Chancellor of Italy. Between 1159 and 1167, Rainald of Dassel was Archbishop of Cologne, as well as being Imperial Chancellor and adviser to Emperor Frederick Barbarossa.

In 1074 the commune was formed. By the 13th century, the relationship between the city of Cologne and its archbishop had become difficult, and after the Battle of Worringen in 1288, the forces of Brabant and the citizenry of Cologne captured the Archbishop Siegfried of Westerburg (1274–97),[1] resulting in an almost complete freedom for the city; to regain his liberty, the archbishop recognized the political independence of Cologne, but reserved certain rights, notably the administration of justice.

Cologne effectively became a free city after 1288; this status was formally confirmed in 1475. The Archbishopric of Cologne was a state of its own within the Holy Roman Empire, but Cologne was independent so the archbishops were usually not allowed to enter the city. Thus they took up residence in Bonn and later in Brühl until they returned in 1821. From 1583 to 1761, all ruling archbishops came from the Wittelsbach dynasty . As powerful electors, the archbishops repeatedly challenged the free status of Cologne during the 17th and 18th century, resulting in complicated legal affairs, which were handled by diplomatic means, usually to the advantage of the city.

In the period of the persecution of witches (1435 – 1655) 37 people were executed in Cologne, mostly during the reign of the Archbishop of Cologne Ferdinand of Bavaria.

The City Council of Cologne issued a resolution on June 28, 2012 to exonerate Katharina Henot and the other victims of the persecution of witches in Cologne.

Hanseatic League

Long-distance trade in the Baltic intensified, as the major trading towns came together in the Hanseatic League, under the leadership of Lübeck. It was a business alliance of trading cities and their guilds that dominated trade along the coast of Northern Europe and flourished from the 1200 to 1500, and continued with lesser importance after that. The chief cities were Cologne on the Rhine River, Hamburg and Bremen on the North Sea, and Lübeck on the Baltic.[2] Cologne was a leading member of the "Hanse" (Hanseatic League), especially through trading with England. The Hanse gave merchants special privileges in member cities, which dominated trade in the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. Cologne's hinterland in Germany gave it an added advantage over the other Hanseatic cities, and it became the largest city in Germany and the region. Thus Cologne's central location on the Rhine river placed it at the intersection of the major trade routes between east and west and was the basis of Cologne's growth.[3] The economic structures of medieval and early modern Cologne were based on the city's major harbor, its location as a transport hub and its entrepreneurial merchants who built ties with merchants in other Hanseatic cities.[4]

The city was proud to build and maintain the great Cologne Cathedral, with sacred relics that made it the destination for many worshippers. With the bishop not resident in the city, it was ruled by patricians (merchants carrying on long-distance trade). The craftsmen formed guilds, governed by strict rules, which sought to obtain control of the towns; a few were open to women. Society was divided into sharply demarcated classes: the clergy, physicians, merchants, various guilds of artisans; full citizenship was not available to paupers. Political tensions arose from issues of taxation, public spending, regulation of business, and market supervision, as well as the limits of corporate autonomy.[5]

French occupation

The French Revolutionary Wars resulted in the occupation of Cologne and the Rhineland in 1794. In the following years the French consolidated their presence. In 1798 Cologne became an arrondissement in the newly created Département de la Roer. In the same year the University of Cologne was closed. In 1801 all citizen of Cologne were granted the French citizenship. In 1804 Napoléon Bonaparte visited the city together with his wife Joséphine de Beauharnais. The French occupation of Cologne ended in 1814.

Prussian period

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

Cologne Cathedral

In 1814, Cologne was occupied by Prussian and Russian troops. In 1815, Cologne and the Rhineland were allocated to Prussia.

Weimar Republic

From the end of World War I until 1926 Cologne was occupied by the British Army of the Rhine under the terms of the armistice and the subsequent Versailles Peace Treaty.[6] Contrary to the harsh measures taken by French occupation troops, the British acted with more tact towards the local population. Mayor of Cologne from 1917 until 1933 and future West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer acknowledged the political impact of this approach, especially that the British opposed French plans for a permanent Allied occupation of the Rhineland.

As part of the de-militarization of the Rhineland the fortifications had to be dismantled. This was taken as an opportunity to create two green belts (Grüngürtel) around the city by converting the fortifications and their clear fields for fire into large public parks. However this project was not completed until 1933.

In 1919 the University of Cologne, closed by the French in 1798, was founded anew. This re-foundation was considered a substitute for the German University of Strasbourg that became part of France just as the rest of Alsace. Cologne prospered during the Weimar Republic and progress was made especially in respect to public governance, city planning and social affairs. Social housing projects were considered exemplary and copied by other German cities.

As Cologne competed for hosting the Olympics a modern sports stadium was erected at Müngersdorf. Beginning of the 1920s civil aviation was readmitted and Cologne Butzweilerhof Airport soon became a hub for national and international air traffic. Second in Germany only to Berlin Tempelhof Airport.

Third Reich

At the beginning of the Third Reich, Cologne was seen as a difficult territory by the Nazis because of deep-rooted communist and Catholic influences on the city. The Nazis were always struggling for control of the city.

Local elections on 13 March 1933 resulted in the NSDAP winning 39.6% of all votes, however the catholic Zentrum Party came in second with 28.3%, followed by the social-democratic SPD with 13.2% and the communist KPD with 11.1%. One day later, on 14 March, Nazi followers occupied the city hall and took over government. Communist and Social Democratic members of the city assembly were imprisoned and Mayor Adenauer was dismissed by the new powerholders.

It was planned to rebuild a large part of the inner city, with a main road connecting the Deutz station and the main station, which was to be moved from next to the cathedral to an area adjacent to today's university campus, with a huge field for rallies, the Maifeld, next to the main station. The Maifeld, between the campus and the Aachener Weiher artificial lake, was the only part of this over-ambitious plan to be realized before the start of the war. After the war, the remains of the Maifeld were buried with rubble from bombed buildings and turned into a park with rolling hills, which was christened Hiroshima-Nagasaki-Park in August, 2004, as a memorial to the victims of the nuclear bombs of 1945. An inconspicuous memorial to the victims of the Nazi regime is situated on one of the hills.

On the night of 30/31 May 1942 Cologne was the target for the first 1,000 bomber raid of the war. The number of persons reported killed was between 469 and 486, around 90% of them civilians. More than 5,000 people were injured and more than 45,000 lost their homes. It was estimated that up to 150,000 of Cologne's population of around 700,000 left the city after the raid. The Royal Air Force (RAF) lost 43 aircraft out of the 1,103 bombers sent. At the end of World War II, 90% of Cologne's buildings were destroyed by Allied aerial bombing raids, most of them flown by the RAF.

On 10 November 1944 a dozen members of the anti-Nazi Ehrenfeld Group were hung in public. Six of them were 16-year-old boys of the Edelweiss Pirates youth gang, including Barthel Schink; Fritz Theilen survived.

Bookseller Gerhard Ludwig, who worked for the influential publisher Neven du Mont in 1941, was dismissed immediately when he got into trouble with the Gestapo for political reasons. Upon his return to Cologne after his release from Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1946, editor Neven du Mont spotted him and complained about the release of prisoners from the camps - he still saw them as "criminals".

The outskirts of Cologne were reached by US-troops on 4 March 1945. The inner city at the left bank of the Rhine was captured on 6 March 1945 in half a day, meeting minor resistance only. Because the Hohenzollernbrücke was destroyed on retreat by German pioneers, the boroughs at the right bank of the river remained under German control until mid of April 1945.[7]

Jews in Cologne

As early as 321 AD, an edict by the Emperor Constantine allowed Jews to be elected to the City Council. The first pogrom against the Jews was in 1349, when they were used as scapegoats for the Black Death, and therefore burnt in an auto de fe.[8] In 1424 they were evicted from the city, but were allowed back again in 1798.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, the Jewish population of Cologne was about 20,000. By 1939, 40% of the city's Jews had emigrated. The vast majority of those who remained had been deported to concentration camps by 1941. The trade fair grounds next to the Deutz train station were used to herd together the Jewish population for deportation to the death camps and for disposal of their household goods by public sale.

On Kristallnacht in 1938, Cologne's synagogues were violated or set on fire.

Postwar Cologne

Despite Cologne being the largest city in the region nearby, Düsseldorf was chosen as the political capital of the newly set-up Federal State North Rhine-Westphalia. With Bonn being chosen as the (provisional) capital of the Federal Republic, Cologne took benefit being sandwiched between the two important political centers of former West Germany. The city became home to a large number of Federal agencies and organizations. After reunification in 1990 a new situation has been politically co-ordinated with the new federal capital city of Berlin.

In 1945 architect and urban planner Rudolf Schwarz called Cologne the "world's greatest heap of debris". Schwarz designed the masterplan of reconstruction in 1947, which called for the construction of several new thoroughfares through the downtown area, especially the 'Nord-Süd-Fahrt' (North-South-Drive). The Masterplan took into consideration the fact that even shortly after the war a large increase in automobile traffic could be anticipated. Plans for new roads had already to a certain degree evolved under the Nazi administration, but the actual construction became easier in times when the majority of downtown lots were undeveloped. The destruction of famous Twelve Romanesque churches like St. Gereon's Basilica, Great St. Martin, St. Maria im Capitol and about a dozen others in World War II meant a tremendous loss of cultural substance to the city. The rebuilding of those churches and other landmarks like the Gürzenich was not undisputed among leading architects and art historians at that time, but in most cases, civil intention prevailed. The reconstruction lasted until the 1990s, when Romanesque church of St. Kunibert was finished.

It took some time to rebuild the city. In 1959 the city's population reached pre-war numbers again. Afterwards the city grew steadily, and, in 1975, the number exceeded 1 million inhabitants for about one year. Since then, the number has lingered just below this point.

In the 1980s and 1990s Cologne's economy prospered from two factors: First, the steady growth in the number of media companies, pertaining to both the private and the public sector. Catering especially to these companies is the newly developed Media Park, which creates a strongly visual focal point in downtown Cologne and includes the KölnTurm, one of Cologne's most prominent highrises. And second, a permanent improvement of the diverse traffic infrastructure, which makes Cologne one of the most easily accessible metropolitan areas in Central Europe.

Due to the economic success of the Cologne Trade Fair, the city arranged a large extension to the fair site in 2005. At the same time the original buildings, which date back to the 1920s are rented out to RTL, Germany's largest private broadcaster, as their new corporate headquarter.

A controversy started after Muslims in Cologne sought to build a mosque.[9]

Most important for the history of Cologne since the Middle Ages is the City Archive Cologne, which has been the largest in Germany. Its building collapsed during the construction of an extension to the underground railway system on 3 March 2009 [citation needed].

See also

References

- ^ Harry de Quetteville. "History of Cologne". The Catholic Encyclopedia, Nov 28, 2009.

- ^ James Westfall Thompson,Economic and Social History of Europe in the Later Middle Ages (1300-1530) (1931) pp. 146-79

- ^ Paul Strait, Cologne in the Twelfth Century (1974)

- ^ Joseph P. Huffman, Family, Commerce, and Religion in London and Cologne (1998) covers from 1000 to 1300.

- ^ David Nicholas, The Growth of the Medieval City: From Late Antiquity to the Early Fourteenth Century (1997) pp 69-72, 133-42, 202-20, 244-45, 300-307

- ^ Cologne Evacuated, TIME Magazine, February 15, 1926

- ^ "Trotz Durchhalteparolen wenig Widerstand - Die US-Armee nimmt Köln ein". Sixty years ago [Vor 60 Jahren] on www.wdr.de (in German). Westdeutscher Rundfunk. 7 March 2005. Retrieved 29 Oktober 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Liber Chronicarum Mundi

- ^ Harry de Quetteville. "Huge mosque stirs protests in Cologne". Telegraph, June 26, 2007.

Further reading

- "Cologne", The Rhine from Rotterdam to Constance, Leipsic: Karl Baedeker, 1882, OCLC 7416969

- "Cologne", The Encyclopaedia Britannica (11th ed.), New York: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1910, OCLC 14782424

- "Cologne", The Rhine, including the Black Forest & the Vosges, Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1911, OCLC 21888483