Guillotine

The guillotine (/ˈɡɪlətiːn/ or /ˈɡiː.ətiːn/; French: [ɡijɔtin]) is a device designed for carrying out executions by decapitation. It consists of a tall upright frame in which a weighted and angled blade is raised to the top and suspended. The condemned person is secured at the bottom of the frame, with his or her neck held directly below the blade. The blade is then released, to fall swiftly and sever the head from the body. The device is best known for its use in France, in particular during the French Revolution, when it "became a part of popular culture, celebrated as the people's avenger by supporters of the Revolution and vilified as the pre-eminent symbol of the Reign of Terror by opponents."[1] However, it continued to be used long after the Revolution and remained France's standard method of judicial execution until the abolition of capital punishment by President François Mitterrand in 1981.[2] The last person guillotined in France was Hamida Djandoubi, on 10 September 1977.

The guillotine has also been employed in other countries. In Germany, it saw rapid and prolific use during the Third Reich and was used once by West Germany in 1949 and by the German Democratic Republic as late as 1966.

Early guillotine

There were guillotine-like devices in countries other than France before 1792. A number of countries, especially in Europe, continued to employ this method of execution into modern times.

Although sources assert that the device was invented in the late 18th century, other accounts recognise that similar 'decapitation machines' have a long history. The Halifax Gibbet was a monolithic wooden structure consisting of two wooden uprights, capped by a horizontal beam, of a total height of 15 feet. The blade was an axe head weighing 3.5 kg, attached to the bottom of a massive wooden block that slid up and down via grooves in the uprights. This device was mounted on a large square platform four feet high. The Halifax Gibbet was certainly substantial, but no date of first use has been made certain yet. The first recorded execution in Halifax dates from 1280, but that execution may have been by sword, axe, or by use of the Gibbet. Executions took place in the town's Market Place on Saturdays, and the machine remained in use until Oliver Cromwell forbade capital punishment for petty theft. It was used for the last time, for the execution of two criminals on a single day, on April 30, 1650.

Another early example is immortalised in the picture 'The execution of Murcod Ballagh near to Merton in Ireland 1307'. As the title suggests, the victim was called Murcod Ballagh, and he was decapitated by equipment looking remarkably similar to the later French guillotines. Another unrelated picture depicts an execution with elements of both a guillotine-style device and a traditional beheading. While the condemned is lying on a bench, a device holds an axe head in position above the neck. The executioner, who is shown wielding a large hammer, strikes down on the mechanism and drives the blade down. Traditional execution by decapitation by sword or axe were notably gruesome, and the aforementioned design was probably conceived in an attempt to improve the accuracy and effectiveness; however, no reference to its actual use has been found.

French Revolution

On 10 October 1789, Doctor Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, a French physician, stood before the National Assembly and proposed the following six articles in favour of the reformation of capital punishment:

- Article 1: All offences of the same kind will be punished by the same type of punishment irrespective of the rank or status of the guilty party.

- Article 2: Whenever the Law imposes the death penalty, irrespective of the nature of the offence, the punishment shall be the same: decapitation, effected by means of a simple mechanism.

- Article 3: The punishment of the guilty party shall not bring discredit upon or discrimination against his family.

- Article 4: No one shall reproach a citizen with any punishment imposed on one of his relatives. Such offenders shall be publicly reprimanded by a judge.

- Article 5: The condemned person's property shall not be confiscated.

- Article 6: At the request of the family, the corpse of the condemned man shall be returned to them for burial and no reference to the nature of death shall be registered.[3]

Sensing the growing discontent, Louis XVI banned the use of the breaking wheel.[4] In 1791, as the French Revolution progressed, the National Assembly researched a new method to be used on all condemned people regardless of class. Their concerns contributed to the idea that the purpose of capital punishment was simply to end life rather than to inflict pain.[4]

A committee was formed under Antoine Louis, physician to the King and Secretary to the Academy of Surgery.[4] Joseph-Ignace Guillotin was also on the committee. The group was influenced by the Italian Mannaia (or Mannaja), the Scottish Maiden and the Halifax Gibbet, which was fitted with an axe head weighing 7 pounds 12 ounces (3.5 kg).[5] While these prior instruments usually crushed the neck or used blunt force to take off a head, devices also usually used a crescent blade and a lunette (a hinged two part yoke to immobilize the victim's neck).[4]

Laquiante, an officer of the Strasbourg criminal court,[6] made a design for a beheading machine and employed Tobias Schmidt, a German engineer and harpsichord maker, to construct a prototype.[7] Antoine Louis is also credited with the design of the prototype. An apocryphal story claims that King Louis XVI (an amateur locksmith) recommended that a triangular blade with a beveled edge be used instead of a crescent blade,[4] but it was Schmidt who suggested placing a straight blade at a 45 degree angle.[8] The first execution by guillotine was performed on highwayman Nicolas Jacques Pelletier[9] on 25 April 1792.[10][11][12] He was executed in front of what is now the city hall of Paris (Place de l'hôtel de ville). All citizens deemed guilty of a crime punishable by death were from then on executed there, until the scaffold was moved on August 21 to the Place du Carrousel.

The machine was successful as it was considered a humane form of execution, contrasting with the methods used in pre-revolutionary, Ancien Régime France. In France, before the guillotine, members of the nobility were beheaded with a sword or axe, which typically took at least two blows to kill the condemned, while commoners were usually hanged, a form of death that could take minutes or longer. Other more gruesome methods of executions were also used, such as the wheel or burning at the stake. In the case of decapitation, it also sometimes took repeated blows to sever the head completely, and it was also very likely that the condemned would slowly bleed to death before the head could be fully severed. The condemned or their family would sometimes pay the executioner to ensure that the blade was sharp, to achieve a quick and relatively painless death.

The guillotine was thus perceived to deliver an immediate death without risk of suffocation. Furthermore, having only one method of civil execution was seen as an expression of equality among citizens. The guillotine was then the only civil legal execution method in France until the abolition of the death penalty in 1981,[13] apart from certain crimes against the security of the state, or for the death sentences passed by military courts,[14] which entailed execution by firing squad.[15]

Reign of Terror

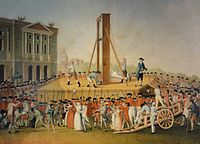

The period from June 1793 to July 1794 in France is known as the Reign of Terror or simply "the Terror". The upheaval following the overthrow of the monarchy, invasion by foreign monarchist powers and the revolt in the Vendée combined to throw the nation into chaos and the government into frenzied paranoia. Most of the democratic reforms of the revolution were suspended and large-scale executions by guillotine began. The first political prisoner to be executed was Collenot d'Angremont of the National Guard, followed soon after by the King's trusted collaborator in his ill-fated attempt to moderate the Revolution, Arnaud de Laporte, both in 1792. Former King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette were executed in 1793. Maximilien Robespierre became one of the most powerful men in the government, and the figure most associated with the Terror. The Revolutionary Tribunal sentenced thousands to the guillotine. Nobility and commoners, intellectuals, politicians and prostitutes,[citation needed] all were liable to be executed on little or no grounds; suspicion of "crimes against liberty" was enough to earn one an appointment with "Madame Guillotine" or "The National Razor". Estimates of the death toll range between 16,000 and 40,000.[16]

At this time, Paris executions were carried out in the Place de la Revolution (former Place Louis XV and current Place de la Concorde); the guillotine stood in the corner near the Hôtel Crillon where the statue of Brest can be found today.

For a time, executions by guillotine were a popular entertainment that attracted great crowds of spectators. Vendors would sell programs listing the names of those scheduled to die. Many people would come day after day and vie for the best locations from which to observe the proceedings; knitting women (tricoteuses) formed a cadre of hardcore regulars, inciting the crowd in the role of cheerleaders. Parents would bring their children. By the end of the Terror, the crowds had thinned drastically. Repetition had staled even this most grisly of entertainments, and audiences grew bored.

Eventually, the National Convention had enough of the Terror, partially fearing for their own lives, and turned against Maximilien Robespierre. He was arrested, and on 28 July 1794, was executed in the same fashion as those whom he had condemned. This arguably ended the Terror, as the French expressed their discontent with Robespierre's policy by guillotining him.[17]

Retirement

After the French Revolution, the executions began again in the city center. On February 4, 1832, the guillotine was moved to behind the church of Saint Jacques, just before being moved again, to the Grande Roquette prison, on November 29, 1851.

On August 6, 1909, the guillotine was used on the junction of Arago Boulevard and Rue de la Santé, behind the prison which bears the same name.

The last public guillotining in France was of Eugen Weidmann, who was convicted of six murders. He was beheaded on 17 June 1939, outside the prison Saint-Pierre, rue Georges Clemenceau 5 at Versailles, which is now the Palais de Justice. A number of problems with that execution (inappropriate behavior by spectators, incorrect assembly of the apparatus, and the fact it was secretly filmed) caused the authorities to conduct future executions in the prison courtyard.[citation needed]

The guillotine remained the official method of execution in France until the death penalty was abolished in 1981.[2] The last guillotining in France was that of torture-murderer Hamida Djandoubi on September 10, 1977.

In the late 1840s the Tussaud brothers Joseph and Francis, gathering relics for Madame Tussauds wax museum, visited the aged Henry-Clément Sanson, grandson of the executioner Charles Henri Sanson, from whom they obtained parts, the knife and lunette, of one the original guillotines used during the Age of Terror. The executioner had "pawned his guillotine, and got into woeful trouble for alleged trafficking in municipal property".[18]

Elsewhere

In Antwerp (Belgium), the last person to be beheaded was Francis Kol. Convicted for robbery with murder, he underwent his punishment on 8 May 1856. During the period from March 19, 1798, until March 30, 1856, Antwerp counted 19 beheadings.[19]

In Germany, where the guillotine is known as Fallbeil ("falling axe"), it was used in various German states from the 17th century onwards, becoming the preferred method of execution in Napoleonic times in many parts of Germany. The guillotine and the firing squad were the legal methods of execution during the German Empire (1871–1918) and the Weimar Republic (1919–1933).

The original German guillotines resembled the French Berger 1872 model, but they eventually evolved into more specialised machines largely built of metal with a much heavier blade enabling shorter uprights to be used. Accompanied by a more efficient blade recovery system and the eventual removal of the tilting board (or bascule) this allowed a quicker turn-around time between executions, the condemned being decapitated either face-up or face-down, depending on how the executioner predicted they would react to the sight of the machine. Those deemed likely to struggle were backed up from behind a curtain to shield their view of the device.

In 1933, Adolf Hitler had a guillotine constructed and tested. He was impressed enough to order 20 more constructed and pressed into immediate service.[4][unreliable source?] National Socialist records indicate that between 1933 and 1945, 16,500 people were executed by guillotine in Germany and Austria.[4] It was used for the last time in West Germany in 1949 (in the execution of Richard Schuh) and in East Germany in 1966 (in the execution of Horst Fischer).[citation needed] In Switzerland it was used for the last time by the canton of Obwalden in the execution of murderer Hans Vollenweider in 1940.

The Scottish Maiden (supposedly based on the Halifax Gibbet) was introduced to Edinburgh by James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton in the 16th century and remained in use until 1708. The scaffold itself is now housed in the National Museum of Scotland.

In Sweden, where beheading became the mandatory method of execution in 1866, the guillotine replaced manual beheading in 1903 and was used only once, in the execution of murderer Alfred Ander in 1910 at Långholmen Prison, Stockholm.

In South Vietnam, after the Diệm regime enacted the 10/59 Decree in 1959, mobile special military courts dispatched to the countryside to intimidate the rural peoples used guillotines belonging to the former French colonial power to carry out death sentences on the spot.[20] One such guillotine is still on show at the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City.[21]

Living heads

It has been suggested that this article be merged with Decapitation. (Discuss) Proposed since December 2011. |

From its first use, there has been debate as to whether the guillotine always provided a swift death as Guillotin had hoped. With previous methods of execution intended to be painful, there was little concern about the suffering inflicted. As the guillotine was invented specifically to be humane, however, the issue was seriously considered. The blade cuts quickly enough so that there is relatively little impact on the brain case, and perhaps less likelihood of immediate unconsciousness than with a more violent decapitation, or long-drop hanging.

Audiences to guillotinings told numerous stories of blinking eyelids, speaking, moving eyes, movement of the mouth, even an expression of "unequivocal indignation" on the face of the decapitated Charlotte Corday when her cheek was slapped.

The following report was written by a Dr. Beaurieux, who experimented with the head of a condemned prisoner by the name of Henri Languille, on 28 June 1905:

- Here, then, is what I was able to note immediately after the decapitation: the eyelids and lips of the guillotined man worked in irregularly rhythmic contractions for about five or six seconds. This phenomenon has been remarked by all those finding themselves in the same conditions as myself for observing what happens after the severing of the neck …

- I waited for several seconds. The spasmodic movements ceased. […] It was then that I called in a strong, sharp voice: "Languille!" I saw the eyelids slowly lift up, without any spasmodic contractions – I insist advisedly on this peculiarity – but with an even movement, quite distinct and normal, such as happens in everyday life, with people awakened or torn from their thoughts.

- Next Languille's eyes very definitely fixed themselves on mine and the pupils focused themselves. I was not, then, dealing with the sort of vague dull look without any expression, that can be observed any day in dying people to whom one speaks: I was dealing with undeniably living eyes which were looking at me. After several seconds, the eyelids closed again […].

- It was at that point that I called out again and, once more, without any spasm, slowly, the eyelids lifted and undeniably living eyes fixed themselves on mine with perhaps even more penetration than the first time. Then there was a further closing of the eyelids, but now less complete. I attempted the effect of a third call; there was no further movement – and the eyes took on the glazed look which they have in the dead.[22]

Anatomists and other scientists in several countries have tried to perform more definitive experiments on severed human heads as recently as 1956.[citation needed] Inevitably, the evidence is only anecdotal. What appears to be a head responding to the sound of its name, or to the pain of a pinprick, may be only random muscle twitching or automatic reflex action, with no awareness involved. At the very least, it seems that the massive drop in cerebral blood pressure would cause a victim to lose consciousness in a few seconds.[23][unreliable source?]

Names for the Guillotine

During the span of its usage, the guillotine has gone by many names, some of which include:

- La Monte-à-regret (The Regretful Climb)[24][25]

- Le Rasoir National (The National Razor)[25]

- Le Vasistas or La Lucarne (The Fanlight)[25][26]

- La Veuve (The Widow)[25]

- Le Moulin à Silence (The Silent Mill)[25]

- Louisette or Louison (from the name of prototype designer Antoine Louis)[25]

- Madame La Guillotine[27]

- Mirabelle (from the name of Mirabeau)[25]

- La Bécane (The Machine)[25]

- Le Massicot (The Cutter)[26]

- La Cravate À Capet (The Necktie of Capet)[26]

- La Raccourcisseuse Patriotique (The Patriotic Shortener)[26]

- La demi-lune (The Half-Pipe)[26]

- Les Bois de Justice (Wooden Justice)[26]

- La Bascule à Charlot (Charlot's Rocking-chair)[26]

- Le Prix Goncourt des Assassins (The Goncourt Prize for Murderers)[26]

Guillotine types

-

Replica of the Halifax Gibbet

-

The Scottish Maiden on display at the Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh.

-

German Fallbeil of 1854, Munich. (Historic replica 1:6 scale)

-

Guillotine in the Central Military Museum of Algiers, served to execute Algerian nationalists during the Algerian War (1960s)

See also

- Henri Désiré Landru

- Rozalia Lubomirska

- Eugen Weidmann

- Marcel Petiot

- Bals des victimes

- Flying guillotine (weapon)

- Plötzensee Prison

- Use of capital punishment by nation

References

Footnotes

- ^ R. Po-chia Hsia, Lynn Hunt, Thomas R. Martin, Barbara H. Rosenwein, and Bonnie G. Smith, The Making of the West, Peoples and Culture, A Concise History, Volume II: Since 1340, Second Edition (New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2007), 664.

- ^ a b Loi n°81-908 du 9 octobre 1981 portant abolition de la peine de mort

- ^ R. F. Opies, "Guillotine" (Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing Ltd, 2003) p. 22

- ^ a b c d e f g Executive Producer Don Cambou (2001). Modern Marvels: Death Devices. A&E Television Networks.

- ^ Parker, John William (26 July 1834), "The Halifax Gibbet-Law", The Saturday Magazine (132): 32

- ^ Croker, John Wilson (1857). Essays on the early period of the French Revolution. J. Murray. p. 549. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ Edmond-Jean Guérin, "1738–1814 – Joseph-Ignace Guillotin : biographie historique d'une figure saintaise", Histoire P@ssion website, accessed 2009-06-27, citing M. Georges de Labruyère in le Matin, 22 Aug. 1907

- ^ "Joseph Ignace Guillotin". whonamedit.com. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ "Crime Library". National Museum of Crime & Punishment. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

[I]n 1792, Nicholas-Jacques Pelletier became the first person to be put to death with a guillotine.

- ^ "Chase's Calendar of Events 2007", p. 291

- ^ Scurr, pp. 222–223

- ^ Abbot, p. 144

- ^ Pre-1981 penal code, article 12: "Any person sentenced to death shall be beheaded."

- ^ Pre-1971 Code de Justice Militaire, article 336: "Les justiciables des juridictions des forces armées condamnés à la peine capitale sont fusillés dans un lieu désigné par l'autorité militaire."

- ^ Pre-1981 penal code, article 13: "By exception to article 12, when the death penalty is handed for crimes against the safety of the State, execution shall take place by firing squad.".

- ^ "Reign of Terror".

- ^ "The Reign of Terror". French Revolution Exhibit. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ^ Leonard Cottrell, Madame Tussaud, Evans Brothers Limited, 1952, p. 142-43.

- ^ Gazet van Mechelen, 8 May 1956

- ^ Mrs Nguyen Thi Dinh (1976). No Other Road to Take: Memoir of Mrs Nguyen Thi Dinh. Cornell University Southeast Asia Program. p. 27. ISBN 0-87727-102-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|nopp=1(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Farrara, Andrew J. (2004). Around the World in 220 Days: The Odyssey of an American Traveler Abroad. Buy Books. p. 415. ISBN 0-7414-1838-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|nopp=1(help); Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Dr. Beaurieux. "Report From 1905". The History of the Guillotine. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ Excerpt from British Medical Journal, Vol 294: February, 1987[dead link], quoting Proges Medical of 9 July 1886, on the subject of research into "living heads".

- ^ http://www.languefrancaise.net/bob/detail.php?id=8

- ^ a b c d e f g h http://www.medarus.org/Medecins/MedecinsTextes/guillotin.html

- ^ a b c d e f g h http://ktakafka.free.fr/F_GUILLOTINE.htm

- ^ http://www.whonamedit.com/synd.cfm/2787.html

Further reading

- Caryle, Thomas. The French Revolution In Three Volumes, Volume 3: The Guillotine. Charles C. Little and James Brown (Little Brown). New York, NY, 1839. No ISBN. (First Edition. Many reprintings of this important history have been done during the last two centuries.)

- Farrell, Simon, Sutherland, Jon. Madame Guillotine: The French Revolution. Armada Books, 1986. ISBN 0-233-97868-2.

- Gerould, Daniel (1992). Guillotine; Its Legend and Lore. Blast Books. ISBN 0-922233-02-0.

External links

- The Guillotine Headquarters with a gallery, history, name list, and quiz.

- L'art de bien couper a French site with a quite complete list of guillotined criminals, pictures, history.

- Bois de justice History of the guillotine, construction details, with rare photos (English)

- Fabricius, Jørn. "The Guillotine Headquarters".

- Does the head remain briefly conscious after decapitation (revisited)? (from The Straight Dope)