Kingdom of Hungary (1000–1526)

Kingdom of Hungary | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

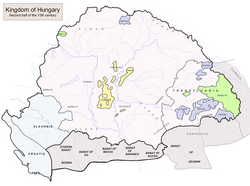

| 1000–1538 | |||||||||||||

Kingdom of Hungary in the 13th century | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Esztergom (1000–1256) Buda (1256–1536) (among others) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Latin (in administration, science and politics); Hungarian, German, Romanian, Ruthenian (vernacular). | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

• 1000–1038 | Stephen I | ||||||||||||

• 1516–1526 | Louis II | ||||||||||||

• 1526–1538 | Disputed | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||

• Coronation of Stephen I | 1000 | ||||||||||||

| 1222 | |||||||||||||

| 1526 | |||||||||||||

| 1538 | |||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | HU | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

| History of Hungary |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Slovakia |

|---|

|

|

|

The medieval Kingdom of Hungary, a multi-ethnic country in Central Europe, came into being when Stephen I, grand prince of the Hungarians, was crowned king in 1000 or 1001. He reinforced central authority and forced his subject to accept Christianity. Although written sources emphasize the role played by German and Italian knights and clerics in the process, a significant part of the Hungarian vocabulary for agriculture, religion and state was taken from Slavic languages. Civil wars, pagan uprisings and the Holy Roman Emperors' attempt to expand their authority jeopardized the new monarchy. Its position stabilized under Ladislaus I (1077–1095) and Coloman (1095–1116). They occupied Croatia and Dalmatia, but both realms reserved their autonomous position.

Rich in uncultivated lands and in silver, gold, and salt deposits, the kingdom became a preferred target of mainly Western European colonists. Their arrival contributed to the development of Esztergom, Székesfehérvár and many other settlements. Situated at the crossroads of international trade routes, Hungary was affected by several cultural trends. Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance buildings, and literary works written in Latin prove the predominantly Roman Catholic character of her culture, but Orthodox, and even non-Christian communities also existed. Latin was the language of legislation, administration and judiciary, but "linguistic pluralism" (János M. Bak)[1] contributed to the survival of a number of tongues, including a great variety of Slavic dialects.

The predominance of royal estates initially ensured the sovereign's preeminent position, but the alienation of royal lands gave rise to the emergence of a self-conscious group of lesser landholders. They forced Andrew II to issue his Golden Bull of 1222, "one of first examples of constitutional limits being placed on the powers of a European monarch" (Francis Fukuyama).[2] The kingdom received a major blow from the Mongol invasion of 1241-42. Thereafter Cuman and Jassic groups were settled in the central lowlands and colonists arrived from Moravia, Poland and other nearby countries. Following a period of interregnum, royal power was restored under Charles I (1308–1342), a scion of the Capetian House of Anjou. Golden and silver mines opened in his reign produced about one third of the world's total production up until the 1490s. The kingdom reached the peak of its power under Louis the Great (1342–1382) who led military campaigns against Lithuania, Southern Italy and other faraway territories.

The expansion of the Ottoman Empire reached the kingdom under Sigismund of Luxemburg (1387–1437). In the next decades, a talented military commander, John Hunyadi directed the fight against the Ottomans. His victory at Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade, Serbia) in 1456 stabilized the kingdom's southern frontiers for more than half a century. The first king of Hungary without dynastic ancestry was Matthias Corvinus (reign: 1458–1490), who led several successful military campaigns and also became the King of Bohemia and the Duke of Austria. With his patronage Hungary became the first European country which adopted the Renaissance from Italy.[3] The territories of the kingdom strongly decreased as a result of the expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. The country was split into two parts in 1538 according to Treaty of Nagyvárad and due to the Ottoman occupation in 1541 the country fell apart into three parts: a central portion controlled by the Ottoman Empire as Budin Province, a western part, called Royal Hungary, whose nobles elected Ferdinand as the king, in hope he would help expelling the Turks, and the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom, out of which later the Principality of Transylvania emerged.

Background

The Hungarians conquered the Carpathian Basin at the turn of the 9th and 10th centuries.[4] Here they found a dominantly Slavic-speaking population.[5] From their new homeland, they launched several plundering expeditions against many regions of Europe.[6][7] Their raids against Western Europe were halted by the future Holy Roman Emperor, Otto I who defeated them in the battle of Lechfeld in 955.[8]

Living in patrilineal families,[9] the Hungarians were organized into clans which formed tribes.[10] The tribal confederation was headed by the grand prince, always a member of the family descending from Árpád, the Hungarians' leader around their "land-taking".[11] Contemporary authors described the Hungarians as nomads, but Ibn Rusta, and others added that they also cultivated arable lands.[12] All the same, the great number of borrowings from Slavic languages[note 1] prove that the Hungarians' way of life underwent fundamental changes in Central Europe.[13] The cohabitation of Hungarians and local ethnic groups is also reflected in the assemblages of the "Bijelo Brdo culture",[14] which emerged in the middle of the 10th century.[15]

Although themselves pagans, the Hungarians demonstrated a tolerate attitude towards Christians, Jews, and Muslims.[16] The Byzantine Church was the first to successfully proselytize among their leaders: in 948 the horka,[11] and around 952 the gyula were baptized in Constantinople.[17] In contrast with them, the grand prince, Géza (c. 970–997) received baptism according to the Latin rite.[18] He erected fortresses and invited foreign warriors to develop a new army based on heavy cavalry.[18][19] Géza also arranged the marriage of his son, Stephen with Giselle of Bavaria, a member of the family of the Holy Roman Emperors.[18][20]

When Géza died in 997,[21] his son had to fight for his succession with Koppány, the eldest member of the House of Árpád.[22] Assisted by German heavy cavalry,[23] Stephen emerged the victor in the decisive battle in 998.[22][24] He applied for a royal crown to Pope Sylvester II who granted his request with the consent of Emperor Otto III.[25]

King St Stephen I (1000–1038)

Stephen I and the foundation of the christian monarchy

"If any warrior debased by lewdness abducts a girl to be his wife without the consent of her parents, we decreed that the girl should be returned to her parents, even if he did anything by force to her, and the abductor shall pay ten steers for the abduction, although he may afterwards have made peace with the girl's parents."

Book One of the Laws of King Stephen I[26]

Stephen was crowned the first king of Hungary on December 25, 1000 or on January 1, 1001.[24] He consolidated his rule by waging successful wars against semi-independent local rulers,[24] including his maternal uncle, Gyula.[23] He proved his kingdom's military strength[27] when repelled an invasion by Conrad II, Holy Roman Emperor in 1030.[28] At that time, marshlands, other natural obstacles and barricades made of stone, earth or timber defended the kingdom's borders.[29] A wide zone known as gyepü was intentionally left uninhabited for defensive purposes along the frontiers.[29] Most early medieval fortresses were made of earth and timber.[30]

Stephen I's views on state administration were summarized around 1015 in a work known as Admonitions.[27] Stating that "the country that has only one language and one custom is weak and fragile", he emphasized the positiv aspects of the arrival of foreigners ("guests").[31] Stephen I developed a state similar to the monarchies of contemporary Western Europe.[24] Counties (districts organized around fortresses and headed by a royal official known as ispán) became the basic units of administration.[23][32]

He founded dioceses and at least one archbishopric, established Benedictine monasteries.[23] He prescribed that every ten villages were to build a parish church.[32] The earliest churches were simple wood constructions,[33] but the royal basilica at Székesfehérvár was built in Romanesque style.[34]

Stephen I's laws were aimed at the adoption, even by force, of a Christian way of life.[35] He especially protected Christian marriage against polygamy and other traditional customs.[33] Decorated belts and other items of pagan fashion also disappeared.[36] Communers started to wear long woolen coats, but wealthier men persisted with their silk kaftans decorated with furs.[36]

From legal perspective, early medieval society was divided into freemen and serfs, but intermediate categories also existed.[37] All freemen had the legal capacity to own property, to sue and to be sued.[38] However, most of them were bound to the monarch or to a wealthier landlord, only "guests" could freely move.[38] Among freemen living in lands attached to a fortress, the "castle warriors" served in the army, and the "castle folk" cultivated the lands, forged weapons or rendered other services.[39][40] All freemen were to pay a special tax, the "pennies of freemen" to the monarchs.[41] With a transitory status between freemen and serfs, peasants known as udvornici were exempt of it.[42] Serfs theoretically lacked legal personality,[43] but in practise they had their own property: they cultivated their masters' land with their own tools, and maintained 50-66 percent of the harvest for themselves.[44]

Stephen I's laws and charters suggest that most communers lived in sedentary communities which formed villages.[45] An average village was made up of no more than 40 semi-sunken timber huts with a corner hearth.[45] Many of the villages were named after a profession,[note 2] implying that the villagers rendered a specific service to their lord.[45]

According to some researchers and the "Magyar nagylexikon"[citation needed] (Hungarian Great Encyclopedia),[46] Stephen's system should be rather called patrimonial than feudal, while others[47] attribute him the introduction of the feudal system.

Between 1038–1242

Pagan revolts, wars and consolidation (1038–1116)

Stephen I survived his son, Emeric which caused a crisis lasting for four decades.[48][49] The monarch who considered his cousin, Vazul unsuitable for the throne named his own sister's son, the Venetian Peter Orseolo as his heir.[28][50] Vazul was blinded, his three sons expelled, thus Peter succeeded his uncle in 1038.[28] His preference for his foreign courtiers led to a rebellion, which ended with his deposition in favor of a local lord, Samuel Aba, himself also related to the royal family.[44][50] Supported by Emperor Henry III, King Peter returned in 1044, but he had to accept the emperor's suzerainty.[28] His second rule ended with a new rebellion, on this occasion aimed at the restoration of paganism.[50]

However, there were many who opposed the destruction of the Christian monarchy.[51] They proposed the crown to Andrew, one of Vazul's sons[44] who returned, defeated King Peter and suppressed the pagans in 1046.[51] His cooperation with his brother, Béla, a talented military commander ensured the Hungarians' victory over Emperor Henry III who attempted to conquer the kingdom between 1050 and 1053.[52]

A new civil war broke out when Duke Béla claimed the crown for himself in 1059, but his three sons accepted the rule of Salomon, Andrew I's son in 1063.[53] Initially, the young king and his cousins cooperated (for instance, they jointly defeated the Pechenegs plundering Transylvania in 1068),[54] but their conflicts caused a new civil war in 1071.[55] It lasted up to Salamon's abdication in favor of one of his cousins, Ladislaus in the early 1080s.[55]

"No one shall buy or sell except in the market. If, in violation of this anyone buys stolen property, everyone shall perish: the buyer, the seller, and the witnesses. If, however, they agreed to sell something of their own, they shall lose that thing and its price, and the witnesses shall lose as much too. But if the deal was made in the market, and agreement shall be concluded in front of a judge, a toll-gatherer, and witnesses, and if the purchased goods later appear to be stolen, the buyer shall escape penalty (...). "

Book Two of the Laws of King Ladislaus I[56]

The new king promulgated laws which prescribed draconian punishments against criminals.[57] His laws also regulated the payment of customs duties, tolls payable at fairs and fords and other royal taxes and of the tithes.[58] He forbade Jews from holding Christian serfs, and introduced laws aiming at the conversion of local Muslims known as böszörménys.[59]

The death of his brother-in-law, King Zvonimir of Croatia in 1089 or 1090 created an opportunity for Ladislaus I to claim his crown.[60][61] Indeed, his troops soon occupied most of Croatia, although a native claimant, Petar Svačić resisted in the Petrova Mounts.[61][62] All the same, hereafter Croatia and Hungary remained closely connected for more than nine centuries.[63]

Ladislaus I appointed his nephew, Álmos to administer Croatia.[61][62] Although a younger son, Álmos was also favored against his brother, Coloman when the king was thinking of his succession.[64] Even so, Coloman succeeded his uncle in 1095, while Álmos received a separate duchy under his brother's suzerainty.[64] Although the brothers' relationship remained tense throughout Coloman's reign (which finally led to the blinding of Álmos and his infant son),[65] they initially cooperated.[citation needed]

In short time after his ascension, Coloman routed two bands of crusaders who were plundering the Western borderlands[66] and defeated Petar Svačić in Croatia.[62][67] The late 14th-century Pacta conventa states that Coloman was crowned king of Croatia after concluding an agreement with twelve local noblemen.[68] Although most probably a forgery, the document reflects the actual status of Croatia proper,[69] which was never incorporated into Hungary.[65] In contrast, the region between the Petrova Mounts and the river Dráva known as Slavonia became closely connected to Hungary.[70] Here many Hungarian noblemen received land grants from the monarchs.[70] Zadar, Split and other Dalmatian towns also accepted Coloman's suzerainty in 1105, but their right to elect their own bishops and leaders remained unchained.[71][72] In Croatia and Slavonia, the sovereign was represented by governors bearing the title ban.[70] Likewise a royal official, the voivode administered Transylvania, the eastern borderland of the kingdom.[73]

Like Ladislaus I, Coloman proved to be a great legislator, but he prescribed less severe punishments than his uncle had done.[74] He ordered that transactions between Christians and Jews were to be put into writing.[75] His laws concerning his Muslim subjects aimed at their conversion, for instance, by obliging them to marry their daughters to Christians.[76] The presence of Jewish and Muslim merchants in the kingdom was due to its role as a crossroad of trading routes leading towards Constantinople, Regensburg and Kiev.[77] Local trade also existed, which enabled Coloman to collect the marturina, the traditional in-kind tax of Slavonia in cash.[78]

The kingdom, with its average population density of four or five people per 1 square kilometre (0.39 sq mi), was sparsely populated.[45] The Olaszi streets or districts in Eger, Pécs and Nagyvárad (Oradea, Romania) point at the presence of "guests" speaking a Western Romance language, while the Németi and Szászi placenames refer to German-speaking colonists.[79] Most subjects of early medieval Hungarian monarchs were peasants.[80] They only cultivated the most fertile lands, and moved further when the lands became exhausted.[45] Wheat was the most widely produced crops, but barley, the raw material for home brew was also grown.[80] Animal husbandry remained an important sector of agriculture, thus millet and oats were produced for fodder.[80] Fishing and hunting also contributed to nourishing, since even peasants were allowed to hunt in royal forests covering large territories.[81]

Colonisation and expansion (1116–1196)

"If anyone of the rank of count has even in a trivial matter offended against the king or, as sometimes happens, has been unjustly accused of this, an emissary from the court, though he be of very lowly station and unattended, seizes him in the midst of his retinue, puts him in chains, and drags him off to various forms of punishment. No formal sentence is asked of the prince through his peers, (...) no opportunity of defending himself is granted the accused, but the will of the prince alone is held by all as sufficient."

Unsuccessful wars with the Republic of Venice, the Byzantine Empire and other neighboring states characterized the reign of Stephen II who succeeded his father in 1116.[83] The earliest mention of the Székelys from the same year is connected to his first war.[84] They lived in scattered communities along the borders,[85] but in the next century their groups were moved to the easternmost regions of Transylvania.[86] Stephen II died childless in 1131.[83] Under the blind Béla II, the kingdom was administered by his queen, Helena of Rascia who annihilated his opposition by ordering its leaders' massacre.[87] Indeed, Boris Kalamanos, an alleged son of King Coloman received no internal support against the king.[83]

Béla II's son, Géza II who succeeded his father in 1141 adopted an active foreign policy.[88] For instance, he supported Uroš II of Rascia against Emperor Manuel I Komnenos.[89] He promoted the colonization of the border zones.[29] Flemish, German, Italian, and Walloon "guests" arrived in great numbers and settled in the Szepesség region (Spiš, Slovakia) and in southern Transylvania.[90][91][92] He even recruited Muslim warriors in the Pontic steppes to serve in his army.[93] Abu Hamid, a Muslim traveler from Al-Andaluz refers to mountains that "contain lots of silver and gold", which points at the importance of mining and gold panning already around 1150.[94]

Géza II was succeeded in 1162 by his eldest son, Stephen III.[83] However, his uncles, Ladislaus II and Stephen IV claimed the crown for themselves.[95] Emperor Manuel I Komnenos took advantage of the internal conflicts and forced the young king to cede Dalmatia and the Szerémség region (Srem, Serbia) to the Byzantines in 1165.[96] Stephen III set an example for the development of towns by granting liberties to the Walloon "guests" in Székesfehérvár, including their immunity of the jurisdiction of the local ispán jurisdiction.[36][97][98]

When Stephen III died childless in 1172, his brother, Béla III ascended the throne.[99][100] He reconquered Dalmatia and the Szerémség in the 1180s.[101][102] A contemporary list shows that more than 50 percent of his revenues derived from the annual renewal of the silver currency, and from tolls, ferries and markets.[103] According to the list, his total income was the equivalent of 32 tonnes of silver per year,[104] but this number is clearly exaggerated.[90] The historian Miklós Molnár suggests an annual income of 23 tonnes of silver, but even this sum would have been the double of contemporary English monarchs' yearly income.[104]

Béla III emphasized the importance of making records on judicial proceedings, which substantiates later Hungarian chronicles' report on his order of the obligatory use of written petitions.[105] Landowners also started to put into writing their transactions, which led to the appearance of the so-called "places of authentication", that is cathedral chapters and monasteries authorized to issue deeds.[106] Their emergence also attests to the employment of an educated staff.[106] Indeed, students from the kingdom studied at the universities of Paris, Oxford, Bologna and Padua from the 1150s.[106]

Further aspects of the 12th-century French culture can also be detected in Béla III's kingdom.[106] His palace at Esztergom was built in the early Gothic style.[107] Achilles and other names known from the Legend of Troy and the Romance of Alexander (two emblematic works of chivalric culture) were also popular among Hungarian aristocrats.[107] According to a widespread view, "Master P", the author of the Gesta Hungarorum, a chronicle on the Hungarian "land-taking" was Béla III's notary.[107][108]

Age of Golden Bulls (1196–1241)

Béla III's son and successor, Emeric had to face revolts stirred up by his younger brother, Andrew.[109] Furthermore, incited by Enrico Dandolo, Doge of Venice, the armies of the Fourth Crusade took Zadar in 1202.[110][111] Emeric was succeeded in 1204 by his son, Ladislaus III.[112] When the infant king died in a year, his uncle ascended the throne.[112] According to some scholars, Adrew II was the first Hungarian king who introduced the feudal system in the Kingdom of Hungary,[113][114] while others talk about feudalism from 1000 B.C., the foundation of the kingdom.[47][115] Stating that "the best measure of a royal grant is its being immeasurable", he distributed large parcels of royal lands among his partisans.[116] Therefore his revenues decreased, which led to the introduction of new taxes and their farming out to Muslims and Jews.[117] Furthermore, freemen living in former royal lands lost their direct contact to the sovereign which threatened their legal status.[118][119]

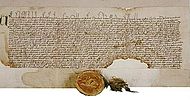

Andrew II was strongly influenced by his wife, Gertrude of Merania.[116] She openly expressed her preference for her German compatriots, which caused her assassination by a group of local lords in 1213.[116][120] A new uprising broke out while the king was in the Holy Land on his crusade in 1217 and 1218.[120] Finally, a movement of the "royal servants" (free landholders who owned service directly to the sovereign) obliged Andrew II to issue his Golden Bull in 1222.[109] It summarized the royal servants' liberties, including their tax exemption.[121] Its last provision authorized the secular and spiritual lords to "resist and speak against" the sovereign "without the charge of high treason".[122][123]

As for Muslims and Jews, the Golden Bull prohibited their employment in royal administration.[124] This ban was confirmed when Andrew II, urged by the prelates, issued the Golden Bull's new variant in 1231, which authorized the archbishop of Esztergom to excommunicate him in case of his depart from its provisions.[125] Since, non-Christians continued to be employed in the royal household, Archbishop Robert of Esztergom placed the kingdom under interdict in 1232.[126] Andrew II was forced to take an oath, which included his promise to respect the privileged position of clergymen and to dismiss all his Jewish and Muslim officials.[127] A growing intolerance against non-Catholics is also demonstrated by the transfer of the Orthodox monastery of Visegrád to the Benedictines in 1221.[128]

Andrew II's several attempts to occupy the neighboring Principality of Halych proved to be unsuccessful on the long run.[129] His son, Béla persuaded a group of Cumans to accept Andrew II's suzerainty in 1228 and established a new march in Oltenia in 1231.[130] Béla IV succeeded his father in 1235.[122] His attempt to reacquire crown lands alienated by his predecessors created a deep rift between the monarch and the lords just as the Mongols were sweeping westward across the Eurasian steppes.[131][132]

The king was first informed on the Mongol threat by Friar Julian, a Dominican monk who visited a Hungarian-speaking population in "Magna Hungaria" (east of the Volga River) in 1235.[122] In the next years, the Mongols routed the Cumans who dominated the western parts of the Eurasian Steppes.[133] A Cuman chieftain, Kuthen agreed to accept Béla IV's supremacy, thus he and his people were allowed to settle in the Great Hungarian Plain.[134] However, the Cumans' nomadic lifestyle caused many conflicts with local communities.[135] The locals even considered them as the Mongols' allies.[136]

Mongol invasion (1241–1242)

[The Mongols] "burnt the church" [in Nagyvárad (Oradea, Romania)]", together with the women and whatever there was in the church. In other churches they perpetrated such crimes to the women that it is better to keep silent (...). Then they ruthlessly beheaded the nobles, citizens, soldiers and canons on a field outside the city. (...) After they had destroyed everything, and an intolerable stench arose from the corpses, they left the place empty. People hiding in the nearby forests came back to find some food. And while they were searching among the stones and the corpses, the" [Mongols] "suddenly returned and of those living whom they found there, none was left alive."

Master Roger's Epistle[137]

Batu Khan, the commander of the Mongol armies invading Eastern Europe demanded Béla IV's surrender without fight in 1240.[138][139] The king refused him and ordered his barons to assemble with their retinue in his camp at Pest.[140] Here a riot broke out against the Cumans and the mob massacred their leader, Kuthen.[134][141] The Cumans soon departed and pillaged the central parts of the kingdom.[142]

The main Mongol army arrived through the northeastern passes of the Carpathian Mountains in March 1241.[134][143] The royal troops met the enemy forces at the river Sajó where the Mongols won a decisive victory on April 11, 1241.[141] From the battlefield, Béla IV fled first to Austria, where Duke Frederick II held him for ransom.[142] Thereafter the king and his family found refugee in the Klis Fortress in Dalmatia.[144]

The Mongols first occupied and thoroughly plundered the territories east of the river Danube.[145] They crossed the river when it was frozen in early 1242.[142] Abbot Hermann of Niederalteich recorded around that time that "the Kingdom of Hungary, which had existed for 350 years, was destroyed".[142][144] In fact, the kingdom did not cease to exist, since the invaders could not take a number of fortresses.[146] Furthermore, Batu Khan ordered the withdrawal of all his troops when he was informed of the death of the Great Khan, Ögödei in March, 1242.[145]

The invasion and the famine following it had catastrophic demographic consequences.[147] At least 15 percent of the population died or disappeared.[148][149] Transcontinental trading routes disintegrated, causing the decline of Bács (Bač, Serbia), Ungvár (Uzhhorod, Ukraine) and other traditional centers of commerce.[150][151] Local Muslim communities ceased to exist, showing that they suffered especially heavy losses.[152]

Last Árpáds (1242–1301)

Béla IV abandoned his attempts to recover former crown lands after the Mongol withdrawal.[153] Instead, he granted large estates to his supporters, and urged them to construct stone-and-mortar castles.[154] He initiated a new wave of colonization which resulted in the arrival of a number of Germans, Moravians, Poles, and Romanians.[155][156] The king reinvited the Cumans and settled them in the plains along the Danube and the Tisza.[157] A group of Alans, the ancestors of the Jassic people seems to have settled in the kingdom around the same time.[158]

New villages appeared which consisted of timber houses built side by side in equal parcels of lands.[159][160] For instance, the settlement network of the so far scarcely inhabited forests of the Western Carpathians (in present-day Slovakia) began to develop under Béla IV.[161] Huts disappeared and new rural houses consisting of a living room, a kitchen and a pantry were built.[162] The most advanced agricultural techniques, including asymmetric heavy ploughs,[163] also spread in the whole kingdom.[159]

Internal migration was likewise instrumental in the development of the new domains emerging in former royal lands.[164] The new landholders granted personal freedom and more favorable financial conditions to those who arrived in their estates, which also enabled the peasants who decided not to move to improve their position.[164] Béla IV granted privileges to more than a dozen of towns, including Nagyszombat (Trnava, Slovakia) and Pest.[165][166]

Threatening letters sent by the khans of the Golden Horde proved that the danger of a new Mongol invasion still existed,[167] but Béla IV adopted an expansionist foreign policy.[155] For instance, Frederick II of Austria died fighting against Hungarian troops in 1246,[168] and Béla IV's son-in-law, Rostislav Mikhailovich annexed a number of territories along the kingdom's southern frontiers.[169][170] However, conflicts between the elderly monarch and his heir, Stephen caused a civil war in the 1260s.[170]

Béla IV and his son jointly confirmed the liberties of the royal servants, hereafter known as noblemen in 1267.[171] By that time, "true noblemen" were legally differentiated from other landholders.[172] They held their estates free of any obligation, but everybody else (even the ecclesiastic nobles, the Romanian cneazes and other "conditional nobles") owned services to their lords in exchange for the lands they held.[173] In growing number of counties, local nobility acquired the right to elect four or two "judges of the nobles" to represent them in official procedures.[174] The idea of equating the Hungarian "nation" with the community of noblemen also emerged in this period.[175] It was first expressed in Simon of Kéza's Gesta Hungarorum, a chronicle written in the 1280s.[176]

The wealthiest landholders forced the lesser nobles to join their retinue which increased their power.[177] One of the barons, Joachim of the Gutkeled clan even captured Stephen V's heir, the infant Ladislaus in 1272.[178] Stephen V died in some months which caused a new civil war between the Csák, Kőszegi, and other leading families who attempted to control the central government in the name of the young Ladislaus IV.[179] He was declared to be of age in 1277 at an assembly of the spiritual and temporal lords and of the noblemen's and Cumans' representatives, but he could not strengthen royal authority.[180] Furthermore Ladislaus IV whose mother, Elisabeth was a Cuman chieftain's daughter preferred his Cuman kin which made him unpopular.[181][182] He was even accused of initiating a second Mongol invasion in 1285, although the invaders were routed by the royal troops.[182][183]

When Ladislaus IV was murdered in 1290, the Holy See declared the kingdom a vacant fief[184][185] and granted it to his sister's son, Charles Martel, crown prince of the Kingdom of Naples.[186] However, the majority of the Hungarian lords supported Andrew, the grandson of Andrew II, although his father's legitimacy was dubious.[186][187] He was the first monarch to take an oath on respecting the liberties of the Church and the nobility before his coronation.[188][189] He regularly convoked the prelates, the lords and the noblemen's representatives to assemblies known as Diets, which started to develop into a legislative body.[186][190]

Late Middle Ages (1301–1526)

Interregnum (1301–1323)

Andrew III died on January 14, 1301.[189] His death created an opportunity for about a dozen lords who had by that time achieved de facto independence of the monarch[189] to strengthen their autonomy.[191] They acquired all royal castles in a number of counties where everybody was obliged either to accept their supremacy or to leave.[192] For instance, Matthew Csák ruled over fourteen counties in the lands now forming Slovakia,[193] Ladislaus Kán administered Transylvania, and Ugrin Csák controlled large territories between the rivers Száva and Dráva.[194]

At the news of Andrew III's death, Charles of Anjou, the late Charles Martel's son hurried to Esztergom where he was crowned king.[195] However, most secular lords opposed his rule and proposed the throne to King Wenceslaus II of Bohemia's namesake son.[196] The young Wenceslaus could not strengthen his position[197] and renounced in favor of Otto III, Duke of Bavaria in 1305.[196] The latter was forced to leave the kingdom in 1307 by Ladislaus Kán.[198] A papal legate persuaded all the lords to accept Charles of Anjou's rule in 1310, but most territories remained out of royal control.[199]

Assisted by the prelates and a growing number of lesser nobles, Charles I launched a series of expeditions against the great lords.[200][201] Taking advantage of the lack of unity among them, he defeated them one by one.[200] He won his first victory in the battle of Rozgony (Rozhanovce, Slovakia) in 1312.[202][203] However, the most powerful lord, Matthew Csák preserved his autonomy up until his death in 1321, while the Babonić and Šubić families were only subjugated in 1323.[200][204]

The Angevins' monarchy (1323–1382)

Charles I introduced a centralized power structure in the 1320s.[205] Stating that "his words has the force of law", he never again convoked the Diet.[205] Even his most faithful partisans depended on revenues from their temporary honours,[104] because the king rarely made land grants.[206] This practice ensured the loyalty of the Drugeths, Lackffys, Szécsényis and other families who emerged in his reign.[206]

The king even afforded to grant privileges which contradicted customary law.[207] For instance, he occasionally authorized daughters of noblemen to inherit their fathers' estates, although local customs required that a deceased nobleman's inherited lands were to be transferred to his agnates in lack of a son.[208] Nevertheless, Roman law never replaced customary which gave rise to the appearance of lay officials who possessed "a good command of Latin and a fair knowledge of common law" (Pál Engel).[209]

Charles I reformed the system of royal revenues and monopolies.[210] For instance, he imposed the "thirtieth" (a tax on goods transferred through the kingdom's frontiers),[210] and authorized landholders to retain one third of the income from mines opened in their estates.[211] The new mines produced around 2,250 kilograms (4,960 lb) of gold and 9,000 kilograms (20,000 lb) of silver annually, which made up more than 30 percent of the world's production up until the Spanish conquest of the Americas in the 1490s.[210] However, most profits from the mines were transferred to Italian and South German merchants, because the value of imported fine textiles and other goods always exceeded the price of cattle and wine exported from the kingdom.[212]

Charles I also ordered the minting of stable golden coins modelled on the florin of Florence.[213] His ban on trading with uncoined gold produced shortage in the European market which lasted until his death in 1342.[214] Thereafter his widow, Elisabeth of Poland transported enormous quantities of gold to Italy in order to promote the claim of their younger son, Andrew to the Kingdom of Naples.[214] Andrew who was Queen Joanna I of Naples's consort was assassined in 1345.[215] His brother, Louis I of Hungary accused the queen of his murder and led two campaigns against her in 1347 and 1350.[216] Although he twice conquered her kingdom,[217] she regained it on both occasions.[218]

The first campaign against Naples was abandoned because of the arrival of the "Black Death".[219] In Hungary, less locals fell victim to the epidemic than in Western Europe, because the kingdom was still an underpopulated territory with well nourished inhabitants.[220] Indeed colonization also continued in the 1300s.[221] The new settlers mainly came from Moravia, Poland and other neighboring countries.[222] They were customarily exempted of taxation for 16 years, which is reflected by the lehota ("lightening") placenames in present-day Slovakia.[223]

Earlier distinctions between freemen, serfs and udvornici disappeared in the 1300s, because all peasants had acquired the right to free movement by the 1350s.[224] Most of them cultivated well defined parcels with a hereditary right to use it for a rent in cash and in-kind "gifts" due to the landowner.[225] The legal position of "true noblemen" was also standardized when the idea of "one and the same liberty" was enacted in 1351.[226] For instance, all noblemen received the right to "adjudicate all offences committed" by the peasants living in their estates (Martyn Rady).[227]

Most towns were still dominated by German merchants,[228] but more and more Croat, Hungarian and Slovak peasants arrived from the nearby villages to settle in the towns in the 1300s.[229] Louis I's Privilegium pro Slavis ("Privileg for the Slavs") from 1381 was the first indication of official bilingualism in a town.[230] It ensured that the Slovaks in Zsolna (Žilina, Slovakia) enjoy the same privileges as the town's German burghers.[230]

Louis I who was heir presumptive to Casimir III of Poland assisted the Poles several times against Lithuania and the Golden Horde.[231] The foundation of Moldavia, a Romanian principality east of the Carpathians is also connected to these campaigns.[232] Along the southern frontiers, Louis I compelled the Venetians to withdrew from Dalmatia in 1358[233] and forced a number of local rulers (including Tvrtko I of Bosnia, and Lazar of Serbia) to accept his suzerainty.[234] However, his vassals often rebelled against him in the 1360s.[235] Bogdan, a Romanian voivode even achieved the independence of Moldavia.[232] Louis I's suzerainty over Moldavia was only restored when he was elected king of Poland in 1370.[235]

His control over Wallachia, the other Romanian principality always remained doubtful.[236] Vladislav I of Wallachia even allied with the emerging Ottoman Empire in 1375.[235] Therefore, Louis I was the first Hungarian monarch who had to fight against the Ottomans.[235]

Religious fanaticism is one of the featuring element of Louis I's reign.[237] He attempted, without success, to convert many of his Orthodox subjects to Catholicism by force.[238] He expelled the Jews around 1360, but allowed them to return in 1367.[239]

New royal castles were erected, for instance, in Visegrád, Diósgyőr, and Zólyom (Zvolen, Slovakia) under the Angevin kings.[240][241] Patricians' houses unearthed at Sopron and other towns, frescoes and sculptures found at many places (including Esztergom and Nagyvárad) point at a flourishing Gothic architecture and art.[240] Codices decorated with miniatures (among them the Illuminated Chronicle) attest to the high level of book illumination.[242] William of Bergzabern, bishop of Pécs founded a university at his see in 1367,[243] but it was closed shortly after his death in 1375.[244]

New consolidation (1382–1437)

Louis I was succeeded in 1382 by his daughter, Mary.[245] However, most noblemen opposed the idea of being ruled by a female monarch.[245] Taking advantage of the situation, a male member of the dynasty, Charles III of Naples claimed the throne for himself.[246] He arrived in the kingdom in September 1385.[245] Although the Diet forced the queen to abdicate and elected Charles of Naples king, the queen's partisans murdered him in February 1386.[245] Paul Horvat, bishop of Zagreb initiated a new rebellion and declared his infant son, Ladislaus of Naples king.[247] They captured the queen in July 1386, but her supporters proposed the crown to her husband, Sigismund of Luxemburg.[248] Queen Mary was soon liberated,[249] but she never again intervened in the government.[250]

Sigismund distributed more than 50 percent of the royal estates to his supporters.[251] Furthermore, large territories in Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia remained controlled by Hrvoje Vukčić Hrvatinić and Ladislaus of Naples's other supporters.[252] When Queen Mary died childless in 1395, her sister, Queen Jadwiga of Poland claimed the throne for herself, but Sigismund's partisans defeated her troops.[253]

In the meantime, Stefan Lazarević of Serbia accepted the Ottoman sultan's suzerainty,[254] thus the Ottoman Empire's expansion reached the southern frontiers of Hungary in 1390.[255] Sigismund decided to organize a crusade against the Ottomans.[256] A great army consisting mainly of French knights assembled, but the crusaders were routed in the battle of Nicopolis in 1396.[257]

The Diet of Temesvár (Timișoara, Romania) of 1397 obliged all landholders to finance the equipment of mounted soldiers for defensive purposes.[258] Thereafter, all landholders provided one archer for each twenty peasant households on their estates.[259] In the same year, Sigismund abolished former immunities of the jurisdiction of county authorities[260] which accelerated the development of county assemblies into important institutions of local autonomy.[260][261]

Sigismund's open bias towards Stibor of Stiboricz, Hermann of Cilli and his (mostly foreign) favorites gave rise to a number of plots.[258] Led by John Kanizsai, archbishop of Esztergom, the native barons even imprisoned him in 1401.[262] For six months, the barons administered the realm in the name of the Holy Crown, "the impersonal sovereign of the kingdom" (Miklós Molnár),[263] but finally restored Sigismund's rule.[262] A group of barons offered the crown to Ladislaus of Naples in 1412,[263] but Sigismund again gained the upper hand.[264] Since Pope Boniface IX supported his opponent, Sigismund prohibited both the proclamation of papal documents without a previous royal consent[265] and the appointment of prelates by the Holy See.[259]

The major towns always remained faithful to Sigismund.[266] He exempted many of them from internal custom duties and even invited their representatives to the Diet in 1405.[266] However, the Diet was not convoked for three decades.[267] The king spent more and more time abroad especially after his election king of the Romans in 1410.[267] The kingdom was governed by his most faithful partisans who were united in a formal league, the Order of the Dragon.[268]

This knightly order was established on the occasion of the royal troop's victory over Hrvoje Hrvatinić in 1408.[269] Thereafter most Dalmatian towns seceded from Ladislaus of Naples,[269] but he soon sold his claims to the Republic of Venice.[270] In the following decade, the republic forced the settlements on the Dalmatian coasts one by one to accept her suzerainty.[271]

On the southern borders, Sigismund attempted to create a buffer zone against the Ottomans.[272] For this purpose, he granted large estates to Stefan Lazarević of Serbia, Mircea I of Wallachia and other neighboring rulers.[273] Furthermore fourteen new fortresses were erected on the Danube frontier under the auspices of the Italian Pipo of Ozora.[274] The first Gypsy groups were also admitted in the kingdom because of their information on the Ottoman Empire's military and their skills in manufacturing weapons.[275]

The Ottomans occupied Golubac Fortress in 1427 and started to regularly plunder the neighboring lands.[274] The Ottoman raids forced many locals to depart for better protected regions.[274] Their place was occupied by South Slavic refugees (mainly Serbs).[274] Many of them were organized into mobile military units[276] known as hussars.[277]

The northern regions of the kingdom (present-day Slovakia) were pillaged in almost every year by Czech Hussites from 1428.[278] However, Hussite ideas spread in the southern counties, mainly among the burghers of the Szerémség.[279] Hussite preachers were also the first to translate the Bible to Hungarian.[279] However, all Hussites were either executed or expelled from the Szerémség in the late 1430s.[279]

Sigismund erected a splendid royal palace (later destroyed by the Ottomans) at Buda.[280] Actually, the town became the kingdom's capital in his reign.[280] The wealthiest landholders also constructed new residences or rebuilt their old fortresses in order to improve comfort.[280] For instance, Pipo of Ozora who employed the painter Masolino da Panicale and one of Brunelleschi's students introduced Renaissance architecture and arts.[281]

The kingdom's defense and Sigismund's active foreign policy demanded new sources of income.[282] For instance, the king imposed "extraordinary" taxes on the prelates and mortgaged 13 Saxon towns in the Szepesség to Poland in 1412.[283] He regularly debased coinage which resulted in a major rebellion of Hungarian and Romanian peasants in Transylvania in 1437.[282][284] It was suppressed by the joint forces of the Hungarian noblemen, Székelys and Transylvanian Saxons who concluded an agreement against the rebels.[272][285]

Age of the two Hunyadis (1437–1490)

Sigismund who had no sons died in late 1437.[286] The Estates elected his son-in-law, Albert V of Austria king.[287] He promised not to make any decisions without consulting the prelates and the lords.[287] The king died of dysentery during an unsuccessful military operation against the Ottomans in 1439.[288]

Although his widow gave birth to a posthumous son, Ladislaus V,[289] most noblemen preferred a monarch capable to fight.[290] They offered the crown to Władysław III of Poland.[290] Both Ladislaus and Władysław were crowned which caused a civil war.[291] John Hunyadi, a talented military leader who supported Władysław rose to prominence during these fights.[291]

King Władysław appointed him (together with his close friend, Nicholas Újlaki) to command the southern defenses in 1441.[291] Hunyadi made several raids against the Ottomans.[292] During his "long campaign" of 1443-1444, the Hungarian forces penetrated as far as Sofia within the Ottoman Empire.[293] The Holy See organized a new crusade, but the Ottomans annihilated the Christian forces in the battle of Varna in 1444.[294]

Since Władysław perished in the battlefield, the Diet of 1445 acknowledged the infant Ladislaus V as rightful monarch.[295] He lived in the court of his relative, Frederick III.[296] Therefore, the Estates appointed seven "captains" (one of them being Hunyadi) to govern the kingdom.[297] The Diet of 1446 elected Hunyadi sole regent,[297] but it was also stipulated that he should convoke the Diet annually.[295][298] At the Diets, all official documents were issued and even speeches could be made in Latin.[229] However, the German-speaking delegates from Pressburg (Bratislava, Slovakia) reported already in 1446 that they could not understand the debates because the noblemen spoke in Hungarian.[229]

Large territories remained independent of the central government in Hunyadi's regency.[298] For instance, Frederick III held several towns along the western borders, and a Czech mercenary, John Jiskra of Brandýs administered many fortresses in the northern regions.[298][299] Even so, Hunyadi was planning to fight against the Ottomans in their own territories.[300] However, his new campaign ended with the Christian forces' defeat in 1448.[300]

Ladislaus V's Austrian and Bohemian subjects forced Emperor Frederick III to hand their young monarch over to his new guardian, Ulrich II, Count of Celje in 1452.[301] Hunyadi also resigned from the regency, but he continued to administer a significant part of royal revenues and many royal fortresses.[302] According to a contemporary proposal for the reform of royal revenues, more than 50 percent thereof (around 120,000 florins) derrived from the royal monopoly on salt and a direct tax payable by the peasantry.[303]

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 demonstrated the beginning of a new phase of Ottoman expansion under Sultan Mehmed II.[304] He occupied Serbia in two years and decided to take Belgrade (Hungarian: Nándorfehérvár), the key of fort at Hungary's southern frontier.[305][306] The defence was organized by John Hunyadi who was assisted by the Franciscan preacher, John of Capistrano.[307] They mobilized 25-30,000 communers, cut the Ottomans' supply lines and forced them to withdraw on July 22, 1456.[308] Hunyadi died in an epidemic in two weeks.[308]

Ulrich of Celje ordered Hunyadi's elder son, Ladislaus to hand over all royal castles held by his father.[309] Ladislaus Hunyadi pretended to accept the command, but his retinue murdered Ulrich of Celje in Belgrade.[310] He and his younger brother, Matthias were arrested in March 1457.[310] However, the former's execution stirred up the lesser nobility to revolt.[310] The king fled to Prague where he died before the end of the year.[307]

A Diet was convoked and the assembled noblemen elected Matthias Hunyadi king in 1458.[311] The young monarch in short time removed the powerful Ladislaus Garay of the office of palatine and his uncle, Michael Szilágyi of the regency.[312] Led by Garay, his opponents offered the crown to Frederick III, but Matthias defeated them and concluded a peace treaty with the emperor in 1464.[312] In the meantime, the zone of buffer states along the kingdom's southern frontiers collapsed with the occupation of Serbia and Bosnia by the ottomans.[313] As an immediate consequence, a great number of Serbian refugees settled in the kingdom.[314]

King Matthias introduced remarkable fiscal and military reforms.[315] First of all, peasants were in each year obliged to pay a lump-sum "extraordinary tax",[316] often without the consent of the Diet.[317] Traditional taxes were renamed in order to abolish earlier exemptions (for instance, the "thirtieth" was collected under the name "duty of the Crown" from 1467).[318] Contemporary estimations suggest that his total yearly income was about 650,000 golden florins.[319] More than 60 percent of his revenues (about 400,000 florins) derrived from the "extraordinary tax", but salt monopoly and coinage still yielded significant income (60-80,000 florins).[319]

Increased royal revenues enabled Matthias to set up and maintain a standing army.[320] Consisting of mainly Czech, German and Hungarian mercenaries, his "Black Army" was one of the first professional military forces in Europe.[321] Matthias strengthened the network of fortresses along the southern frontier,[322] but he did not pursue his father's offensive anti-Ottoman policy.[323] Instead, he launched attacks on Bohemia, Poland, and Austria, arguing that he was trying to forge an alliance strong enough to expel the Ottomans from Europe.[324]

Although his war against the "heretic" George of Poděbrady, king of Bohemia was supported by the Holy See,[325] this reorientation of the kingdom's foreign policy was unpopular.[326] Led by John Vitéz, archbishop of Esztergom, many of Matthias's former supporters rebelled against him in 1471.[326] They offered the throne to Casimir, son of Casimir IV of Poland,[326] but Matthias overcame them without difficulties.[323] His war against Bohemia ended with the Peace of Olomouc of 1478 which confirmed his hold of Moravia, Silesia and Lusatia.[327] In the next decade, Matthias waged a war against Emperor Frederick III which enabled him to occupy Styria and Lower Austria (including Vienna).[328]

Matthias rarely convoked a Diet and governed by royal decrees after 1471.[329] He preferred to employ lesser nobles and even communers instead of aristocrats in state administration.[328] His Decretum Maius of 1486 strengthened the authority of county magistrates by abolishing the palatine's right to convoke judicial assemblies in the counties and by annulling earlier immunities.[330][331] King "Matthias the Just" travelling in disguise throughout his realm in order to suppress corruption became a hero of popular folk tales in some years after his death.[331]

Matthias's court was "unquestionably among the most brilliant in Europe" (Miklós Molnár).[332] His library, the Bibliotheca Corviniana with its 2,000 manuscripts, was the second greatest in size among contemporary book-collections.[333] Matthias was the first monarch north of the Alps to introduce Italian Renaissance style in his realms.[333] Inspired by his second wife, Beatrice of Naples, he had the royal palaces at Buda and Visegrád rebuilt under the auspices of Italian architects and artists after 1479.[333]

Decline (1490–1526)

The magnates, who did not want another heavy-handed king, procured the accession of Vladislaus II, king of Bohemia (Ulászló II in Hungarian history), precisely because of his notorious weakness: he was known as King Dobže, or Dobzse (meaning "Good" or, loosely, "OK"), from his habit of accepting with that word every paper laid before him.[334] The freshly elected King Vladislaus II donated most of the royal estates, régales and royalties to the nobility. By this method, the king tried to stabilize his new reign and preserve his popularity amongst the magnates. After the naive fiscal and land policy of the royal court, the central power began to experience severe financial difficulties, largely due to the enlargement of feudal lands at his expense. The noble estate of the parliament succeeded in reducing the tax burden by 70-80 percent, at the expense of the country ability to defend itself.[335]

Matthias' reforms did not survive the turbulent decades that followed his reign. An oligarchy of quarrelsome magnates gained control of Hungary. They crowned a docile king, Vladislaus II (the Jagiellonian king of Bohemia, who was known in Hungary as Ulaszlo II, 1490–1516) the son of King Casimir IV of Poland, only on condition that he abolish the taxes that had supported Matthias' mercenary army. As a result, the king's army dispersed just as the Turks were threatening Hungary. The magnates also dismantled Mathias' administration and antagonized the lesser nobles. In 1492 the Diet limited the serfs' freedom of movement and expanded their obligations while a large portion of peasants became prospering because of cattle-export to the West. Rural discontent boiled over in 1514 when well-armed peasants preparing for a crusade against Turks rose up under György Dózsa (a borderguard captain) and attacked estates across Hungary. United by a common threat, the magnates and lesser nobles eventually crushed the rebels. Dozsa and other rebel leaders were executed in a most brutal manner.

Shocked by the peasant revolt, the Diet of 1514 passed laws that condemned the serfs to eternal bondage and increased their work obligations. Corporal punishment became widespread, and one noble even branded his serfs like livestock. The legal scholar István Werbőczy included the new laws in his Tripartitum of 1514, which made up the espirit of Hungary's legal corpus until the revolution of 1848. However, the Tripartitum was never used as a code. The Tripartitum gave Hungary's king and nobles, or magnates, equal shares of power: the nobles recognized the king as superior, but in turn the nobles had the power to elect the king. The Tripartitum also freed the nobles from taxation, obligated them to serve in the military only in a defensive war, and made them immune from arbitrary arrest.

When Vladislaus II died in 1516, his ten-year-old son Louis II (1516–26) became king, but a royal council appointed by the Diet ruled the country. Hungary was in a state of near anarchy under the magnates' rule. The king's finances were a shambles; he borrowed to meet his household expenses despite the fact that they totaled about one-third of the national income. The country's defenses sagged as border guards went unpaid, fortresses fell into disrepair, and initiatives to increase taxes to reinforce defenses were stifled. In 1521 Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent recognized Hungary's weakness and seized Belgrade in preparation for an attack on Hungary.

Battle of Mohács (1526)

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2012) |

After that, Louis II and his wife, Maria von Habsburg tried to manage an anti-magnate putsch, but they were not successful. In August 1526,the Ottomans under Suileman the magnificent appeared in southern Hungary,and he marched nearly 100,000 troops into Hungary's heartland. Hungary's forces were just gathering, when the 26,000 strong Hungarian army met the Turks with bad luck in the Battle of Mohács. Hungarians had well-equipped and well-trained troops, and awaited more reinforcements from Croatia and Transylvania, but lacked a good military leader. They suffered bloody defeat leaving 20,000 dead on the field. Louis himself died, thrown from a horse into a bog.

Disintegration (1526–1541)

After Louis's death,the rival factions of Hungarian nobles simultaneously elected two kings, John I Zápolya (1526–40) and Ferdinand of Habsburg (1526–64). Each claimed sovereignty over the entire country but lacked sufficient forces to eliminate his rival. Zápolya, a Hungarian who was military governor of Transylvania, was recognized by the sultan and was supported mostly by lesser nobles opposed to new foreign kings. John I's realm also became an Ottoman vassal in 1529 when he swore fealty to the sultan. Ferdinand, the first Habsburg to occupy the Hungarian throne, drew support from magnates in western Hungary who hoped he could convince his brother, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, to expel the Turks. In 1538 George Martinuzzi, Zápolya's adviser, arranged an agreement between the rivals, called the treaty of Nagyvárad,[336] that would have made Ferdinand sole monarch upon the death of the then-childless Zápolya. The deal collapsed when Zápolya married and fathered a son. Violence erupted, and the Turks seized the opportunity, conquering the city of Buda and then partitioning the country in 1541.

Aftermath

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2012) |

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Bak 1993, p. 269.

- ^ Fukuyama, Francis (February 6, 2012). "What's Wrong with Hungary". Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law (blog). The American Interest.

- ^ Peter Farbaky, Louis A. Waldman (7 November 2011). Italy & Hungary: Humanism and Art in the Early Renaissance. Harvard University Press. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ^ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 6.

- ^ Molnár 2001, pp. 14-16.

- ^ Makkai 1994, p. 13.

- ^ Spinei 2003, pp. 81-82.

- ^ Spinei 2003, p. 28.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 21.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Spinei 2003, pp. 19-22.

- ^ Spiesz et al 2006, p. 28.

- ^ Spinei 2003, p. 57.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 192-193.

- ^ Spinei 2003, p. 16.

- ^ Spinei 2003, pp. 78-79.

- ^ a b c Makkai 1994, p. 16.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 51.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 26.

- ^ Molnár 2001, p. 20.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d Makkai 1994, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Kontler 1999, p. 53.

- ^ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 41.

- ^ The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary, 1000–1301 (Stephen I:27), p. 6.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d Engel 2001, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Sedlar 1994, p. 207.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 56.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 38.

- ^ a b Spiesz et al 2006, p. 29.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 72.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 45-46.

- ^ a b c Makkai 1994, p. 20.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 66-69., 74.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, pp. 68-69.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 69-70.

- ^ Rady 2000, pp. 19-21.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 70.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 74.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 68.

- ^ a b c Makkai 1994, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e Engel 2001, p. 59.

- ^ Miklós Molnár: A Concise History of Hungary (page : 32) Cambridge University Press

- ^ a b Gabriel Ronay: Lost King of England, The Boydell Press, Woodridge, 1989 [1]

- ^ Molnár 2001, p. 26.

- ^ Makkai 1994, pp. 18-19.

- ^ a b c Kontler 1999, p. 59.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 60.

- ^ Spiesz et al 2006, p. 32.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 31.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 251.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 33.

- ^ The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary, 1000–1301 (Ladislas II:7), p. 14.

- ^ Kontler 1999, pp. 61-62.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 62.

- ^ Berend 2006, pp. 75., 237.

- ^ Fine 1991, pp. 283-284.

- ^ a b c Curta 2006, p. 265.

- ^ a b c Goldstein 1999, p. 20.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 63.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 34.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 35.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, pp. 225-226.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 284.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 266-267.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 267.

- ^ a b c Goldstein 1999, p. 21.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 266.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 36.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 355.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 65.

- ^ Berend 2006, pp. 75., 111.

- ^ Berend 2006, p. 211.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 64.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 34., 65.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 60-61.

- ^ a b c Engel 2001, p. 57.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 56.

- ^ The Deeds of Frederick Barbarossa by Otto of Freising and his continuator, Rahewin (1.32/31), p. 67.

- ^ a b c d Kontler 1999, p. 73.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 116.

- ^ Spinei 2003, p. 126.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 116-117.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 50.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Fine 1991, pp. 237-238.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 61.

- ^ Spiesz et al 2006, p. 276.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 352-353.

- ^ Berend 2006, p. 141.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 62.

- ^ Kontler 1999, pp. 73-74.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 53.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 60.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 61.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 74.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 55.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 346.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 7.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 62-63.

- ^ a b c Molnár 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Rady 2000, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Kontler 1999, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Makkai 1994, p. 21.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 11.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 75.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 372.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 61.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 89.

- ^ Charles W. Prévité-Orton: The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History, page: 740

- ^ Pál Engel: Realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, page: 93

- ^ Paul Robert Magocsi: Encyclopedia of Canada's peoples, University of Toronto Press, 1999 [2]

- ^ a b c Engel 2001, p. 91.

- ^ Makkai 1994, p. 23.

- ^ Rady 2000, p. 34.

- ^ Berend 2006, p. 21.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 76.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 94.

- ^ a b c Kontler 1999, p. 77.

- ^ The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary, 1000–1301 (1222:31), p. 35.

- ^ Berend 2006, p. 121.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 96.

- ^ Berend 2006, pp. 156-157.

- ^ Berend 2006, pp. 158-159.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 97.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 89-90.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 387-388., 405-406.

- ^ Makkai 1994, p. 25.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 98.

- ^ Spinei 2003, p. 301.

- ^ a b c Engel 2001, p. 99.

- ^ Spinei 2003, p. 308.

- ^ Berend 2006, p. 99.

- ^ Master Roger's Epistle (ch. 34), p. 201.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 211.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 409-411.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 213.

- ^ a b Spinei 2003, p. 427.

- ^ a b c d Engel 2001, p. 100.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 409.

- ^ a b Spinei 2003, p. 439.

- ^ a b Sedlar 1994, p. 214.

- ^ Spinei 2003, pp. 439., 442.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 413.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 101-102.

- ^ Molnár 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 414.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 103.

- ^ Berend 2006, pp. 242-243.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 80.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 104.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 81.

- ^ Molnár 2001, p. 38.

- ^ Spinei 2003, pp. 104-105.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 105.

- ^ a b Makkai 1994, p. 33.

- ^ Spiesz et al 2006, p. 49.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 113.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 272.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 111.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 112.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 112-113.

- ^ Spiesz et al 2006, p. 34.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 377.

- ^ Kontler 1999, pp. 81-82.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 171-175.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 106.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 120.

- ^ Rady 2000, pp. 91-93.

- ^ Rady 2000, pp. 79., 84., 91-93.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 120-121.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 122.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 121.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 276.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 107-108.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 108.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 108-109.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, pp. 406-407.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 109.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 219.

- ^ Makkai 1994, p. 31.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Engel 2001, p. 110.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 33.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Kontler 1999, p. 84.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 286.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 111., 124.

- ^ Makkai 1994, p. 34.

- ^ Kirschbaum 2005, pp. 44-45.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 126.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 128.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 87.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 129.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 130.

- ^ Makkai 1994, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Kontler 1999, p. 88.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 132.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 131.

- ^ Makkai 1994, pp. 37-38.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 133.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 140.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 89.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 141.

- ^ Rady 2000, pp. 107-109.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 192-193.

- ^ a b c Kontler 1999, p. 90.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 155-156.

- ^ Bak 1994, p. 58.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 346.

- ^ a b Sedlar 1994, p. 348.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 159.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 159-160.

- ^ Molnár 2001, p. 50.

- ^ Molnár 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 93.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 161.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 269.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 270.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 269-270.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 97.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 98.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 175.

- ^ Rady 2000, pp. 57-58.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 261.

- ^ a b c Bak 1993, p. 277.

- ^ a b Kirschbaum 2005, p. 46.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 167.

- ^ a b Georgescu 1991, p. 18.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 27.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 162-165.

- ^ a b c d Engel 2001, p. 165.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 165-166.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 172.

- ^ Molnár 2001, p. 53.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 172-173.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 99.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 147-148.

- ^ Kontler 1999, pp. 99-100.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 472.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 194.

- ^ a b c d Kontler 1999, p. 101.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 195.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 198.

- ^ Bak 1994, p. 54.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 397.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 102.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 199-201.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 398.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 201.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 412.

- ^ Kontler 1999, pp. 102-103.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 424.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 203.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 104.

- ^ a b Sedlar 1994, p. 167.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 219.

- ^ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 53.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 206.

- ^ a b Molnár 2001, p. 56.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 208.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 210.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 106.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 214.

- ^ Molnár 2001, p. 57.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 105.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 29-30.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 489-490.

- ^ a b Bak 1994, p. 61.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 232-234.

- ^ a b c d Engel 2001, p. 237.

- ^ Crowe 2007, p. 70.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 111.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 339.

- ^ Spiesz et al 2006, pp. 52-53.

- ^ a b c Bak 1994, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Engel 2001, p. 241.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 126.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 109.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 227-228.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, p. 30.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, pp. 31., 41.

- ^ Bak 1994, p. 62.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 279.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 112.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 279-280.

- ^ a b Bak 1994, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Engel 2001, pp. 282-283.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 284-285.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 114.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 286-287.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 116.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 288.

- ^ a b Bak 1994, p. 67.

- ^ a b c Engel 2001, p. 289.

- ^ Spiesz et al 2006, p. 54.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 291.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 292.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 117.

- ^ Bak 1994, p. 68.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 295.

- ^ Fine 1991, pp. 568-569.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 251.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 296.

- ^ a b Bak 1994, p. 69.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 118.

- ^ a b c Bak 1994, p. 70.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 298.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 299.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 300-301.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 576.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 121.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 310-311.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 120.

- ^ Bak 1994, p. 71.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 311.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, pp. 225., 238

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 309.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 308-309.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 125.

- ^ Kontler 1999, pp. 123-125.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 303-304.

- ^ a b c Bak 1994, p. 72.

- ^ Bak 1994, pp. 72-73.

- ^ a b Bak 1994, p. 73.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 290.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 316.

- ^ a b Bak 1994, p. 74.

- ^ Molnár 2001, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Engel 2001, p. 319.

- ^ "Hungary—Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ^ Francis Fukuyama: Origins of Political Order: From Pre-Human Times to the French Revolution

- ^ István Keul, Early modern religious communities in East-Central Europe: ethnic diversity, denominational plurality, and corporative politics in the principality of Transylvania (1526–1691), BRILL, 2009, p. 40

Sources

Primary sources

- Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited, Translated and Annotated by Martyn Rady and László Veszprémy) (2010). In: Rady, Martyn; Veszprémy, László; Bak, János M. (2010); Anonymus and Master Roger; CEU Press; ISBN 978-9639776951.

- Master Roger's Epistle to the Sorrowful Lament upon the Destruction of the Kingdom of Hungary by the Tatars (Translated and Annotated by János M. Bak and Martyn Rady) (2010). In: Rady, Martyn; Veszprémy, László; Bak, János M. (2010); Anonymus and Master Roger; CEU Press; ISBN 978-9639776951.

- The Deeds of Frederick Barbarossa by Otto of Freising and his continuator, Rahewin (Translated and annotated with an itroduction by Charles Christopher Mierow, with the collaboration of Richard Emery) (1953). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13419-3.

- The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary, 1000–1301 (Translated and Edited by János M. Bak, György Bónis, James Ross Sweeney with an essay on previous editions by Andor Czizmadia, Second revised edition, In collaboration with Leslie S. Domonkos) (1999). Charles Schlacks, Jr. Publishers. ISBN 88445-29-2.

Secondary sources

- Bak, János M. (1993). "Linguistic pluralism" in Medieval Hungary. In: The Culture of Christendom: Essays in Medieval History in Memory of Denis L. T. Bethel (Edited by Marc A. Meyer); The Hambledon Press; ISBN 1-85285-064-7.

- Bak, János (1994). The late medieval period, 1382–1526. In: Sugár, Peter F. (General Editor); Hanák, Péter (Associate Editor); Frank, Tibor (Editorial Assistant); A History of Hungary; Indiana University Press; ISBN 0-253-20867-X.

- Berend, Nora (2006). At the Gate of Christendom: Jews, Muslims and "Pagans" in Medieval Hungary, c. 1000–c. 1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02720-5.

- Crowe, David M. (2007). A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN. ISBN 978-1-4039-8009-0.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Fine, John V. A. (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth century. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Fine, John V. A. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Georgescu, Vlad (1991). The Romanians: A History. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0-8142-0511-9.

- Goldstein, Ivo (1999). Croatia: A History (Translated from the Croatian by Nikolina Jovanović). McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2017-2.

- Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. (2005). A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival. Palgrave. ISBN 1-4039-6929-9.

- Kontler, László (1999). Millenium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.

- Makkai, László (1994). The Hungarians' prehistory, their conquest of Hungary and their raids to the West to 955 and The foundation of the Hungarian Christian state, 950–1196. In: Sugár, Peter F. (General Editor); Hanák, Péter (Associate Editor); Frank, Tibor (Editorial Assistant); A History of Hungary; Indiana University Press; ISBN 0-253-20867-X.

- Molnár, Miklós (2001). A Concise History of Hungary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66736-4.

- Rady, Martyn (2000). Nobility, Land and Service in Medieval Hungary. Palgrave (in association with School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London). ISBN 0-333-80085-0.

- Reutel, Timothy (2000). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 3, c.900-c.1024. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521364478

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97290-4.

- Spiesz, Anton; Caplovic, Dusan; Bolchazy, Ladislaus J. (2006). Illustrated Slovak History: A Struggle for Sovereignty in Central Europe. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86516-426-0.

- Spinei, Victor (2003). The Great Migrations in the East and South East of Europe from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Century (Translated by Dana Bădulescu). ISBN 973-85894-5-2.