Hippocratic Oath

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

The Hippocratic Oath (Greek ὅρκος horkos) is an oath historically taken by physicians and physician assistants. It is one of the most widely known of Greek medical texts. It requires a new physician to swear, upon a number of healing gods, to uphold specific ethical standards. Of historic and traditional value, the oath is considered a rite of passage for practitioners of medicine in many countries, although nowadays the modernized version of the text varies among them.

Scholars widely believe that Hippocrates, often called the father of medicine in Western culture, or one of his students wrote the oath.[1] The oath is written in Ionic Greek (late 5th century BC),[2] It is usually included in the Hippocratic Corpus.

Classical scholar Ludwig Edelstein proposed that the oath was written by Pythagoreans, an idea that others questioned for lack of evidence for a school of Pythagorean medicine.[3]

Original oath

This is the original version of the Oath:[4]

I swear by Apollo, the healer, Asclepius, Hygieia, and Panacea, and I take to witness all the gods, all the goddesses, to keep according to my ability and my judgment, the following Oath and agreement:

To consider dear to me, as my parents, him who taught me this art; to live in common with him and, if necessary, to share my goods with him; To look upon his children as my own brothers, to teach them this art; and that by my teaching, I will impart a knowledge of this art to my own sons, and to my teacher's sons, and to disciples bound by an indenture and oath according to the medical laws, and no others.

I will prescribe regimens for the good of my patients according to my ability and my judgment and never do harm to anyone.

I will give no deadly medicine to any one if asked, nor suggest any such counsel; and similarly I will not give a woman a pessary to cause an abortion.

But I will preserve the purity of my life and my arts.

I will not cut for stone, even for patients in whom the disease is manifest; I will leave this operation to be performed by practitioners, specialists in this art.

In every house where I come I will enter only for the good of my patients, keeping myself far from all intentional ill-doing and all seduction and especially from the pleasures of love with women or men, be they free or slaves.

All that may come to my knowledge in the exercise of my profession or in daily commerce with men, which ought not to be spread abroad, I will keep secret and will never reveal.

If I keep this oath faithfully, may I enjoy my life and practice my art, respected by all humanity and in all times; but if I swerve from it or violate it, may the reverse be my life.[citation needed]

The original oath broken down

The original Hippocratic Oath can be broken up to cover twelve different areas to which a physician is swearing to; the areas are as follows:[5]

- The first is a covenant with the deity Apollo, who is the god of healing. Most modern oaths have removed this portion; however, the original translation reads "I swear by Apollo the physician…".

- The second is the Covenant with Teachers, and this is done with the pledge of collegiality and financial support.

- Next is the Commitment to Students by the promise to teach those who swear the oath.

- After the Commitment to Students comes the Covenant with Patients, and this is the physician's pledge to use their best ability and judgment.

- The fifth area is Appropriate Means with the use of standard "dietary" care; this is using the established and accepted practices to treat their patients.

- Appropriate Ends is next and says that a doctor is to do what is best for the patient, rather than what is best for the physician.

- The seventh area is the Limits on Ends, which was originally in the oath but has been omitted by many medical schools. The Limit on Ends in the oath said that a doctor would not help a woman have an abortion and that the physician would not administer a lethal drug if asked. Both of these have caused many ethical dilemmas in modern times, with abortion being legal in many countries, prisons using lethal drugs to execute prisoners and physicians practicing euthanasia.

- The next area is Limits on Means; this refers to the leaving of surgeries and specialty care to those who have been trained in that particular specialty.

- Next is Justice; upon taking the oath, the physician is swearing that they will avoid any voluntary act of impropriety or corruption.

- After Justice comes Chastity, which states that a physician will not have any sexual contact with their patients.

- The eleventh area covered is Confidentiality; this simply says that a doctor will not repeat anything that is seen or heard.

- The final area of the oath is Accountability, which is a prayer that the physician be favored by the gods if the oath is kept and punished if it is broken.

When the Oath was rewritten in 1964 by Louis Lasagna, Academic Dean of the School of Medicine at Tufts University, the prayer was omitted, and that version has been widely accepted and is still in use today by many medical schools.[6]

Modern use and relevance

The oath has been modified numerous times. One of the most significant revisions was first drafted in 1948 by the World Medical Association. Called the Declaration of Geneva, it was "intended to be a self-conscious rewriting of the Hippocratic Oath, reaffirming Hippocratism in the face of the shame and tragedy of the German medical experience". The Third Reich variant of the oath asserted that there was life not worth living, this made permissible neglect of and experimentation upon supposedly inferior persons, such as the disabled and people in certain racial categories.

In the 1960s, the Hippocratic Oath was changed to "utmost respect for human life from its beginning", making it a more secular concept, not to be taken in the presence of God or any gods, but before only other people.

While there is currently no legal obligation for medical students to swear an oath upon graduating, 98% of American medical students swear some form of oath, while only 50% of British medical students do. [8] In a 1989 survey of 126 US medical schools, only three reported usage of the original oath, while thirty-three used the Declaration of Geneva, sixty-seven used a modified Hippocratic Oath, four used the Oath of Maimonides, one used a covenant, eight used another oath, one used an unknown oath, and two did not use any kind of oath. Seven medical schools did not reply to the survey. In France, it is common for new medical graduates to sign a written oath.[9][10]

In the United States, the majority of osteopathic medical schools use the Osteopathic Oath as well as the Hippocratic Oath. The Osteopathic Oath was first used in 1938, and the current version has been in use since 1954.

In 1995, Sir Joseph Rotblat, in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize, suggested a Hippocratic Oath for Scientists.

Despite the old Hippocratic Oath prohibiting abortions, it is no longer considered a professional violation of ethics to perform one in the United States.

Lethal injection and the Hippocratic Oath

There has been a large debate on whether a doctor administering or facilitating in a lethal injection to a prisoner is breaking the Hippocratic Oath they took.

In 1991, José High was set to be executed in Georgia, United States. The execution team could not gain access to Jose High's vein due to extreme drug use from his past. The execution team brought in a doctor who had critical care training and was an expert at finding deep veins in the human body. Once the doctor was hired for the sole reason of inserting an IV the doctor at that point became part of the execution team.

Up until this point, doctors would not take part in placing an IV or administering the drugs, they were only there to pronounce the death of the inmate. The execution happened without incident; however, a group of doctors sued the Georgia State Medical Board for not disciplining the doctor, stating that he violated federal law and broke the Hippocratic Oath (although the Hippocratic oath is not legally binding). In response, the Georgia legislature passed laws protecting doctors who take part in lethal injections from civil and criminal prosecution.

Breaking the Hippocratic Oath

There is no direct punishment for breaking the Hippocratic oath in modern days. It can be said that malpractice is the same thing and it carries a wide range of punishments from legal action to civil penalties.[11] In antiquity the punishment for breaking the Hippocratic oath could range from a penalty to losing the right to practice medicine.[12] While there are no direct laws, doctors can still be held accountable through malpractice and other civil and criminal charges.

See also

References

- ^ Farnell, Lewis R. (2004) [1920]. Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality : The Gifford Lectures : Delivered in the University of St. Andrews in the Year 1920. Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-4179-2134-8.

The famous Hippocratean oath may not be an authentic deliverance of the great master, but is an ancient formula current in his school.

- ^ Edelstein, Ludwig (1943). The Hippocratic Oath: Text, Translation and Interpretation. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-8018-0184-6.

- ^ Temkin, Owsei (2001). "On Second Thought". "On Second Thought" and Other Essays in the History of Medicine and Science. Johns Hopkins University. ISBN 978-0-8018-6774-3.

- ^ Jones, W. H. S., ed. (1868). Hippocrates Collected Works (in Greek). Vol. I. Cambridge Harvard University Press. pp. 130–131.

{{cite book}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help) - ^ Hulkower, Raphael (2010). "The History of the Hippocratic Oath: Outdated, Inauthentic, and Yet Still Relevant". The Einstein Journal of Biology and Medicine.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "The Hippocratic Oath Modern Version". University of California San Diego.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ National Library of Medicine 2006

- ^ Dorman, J. (September 1995). "The Hippocratic Oath". Journal of American College Health. 44 (2): 84–88. ISSN 0744-8481. Retrieved 2013-09-20. [dead link]

- ^ Sritharan, Kaji; Georgina Russell; Zoe Fritz; Davina Wong; Matthew Rollin; Jake Dunning; Bruce Wayne; Philip Morgan; Catherine Sheehan (December 2000). "Medical oaths and declarations". BMJ. 323 (7327): 1440–1. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7327.1440. PMC 1121898. PMID 11751345.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Crawshaw, R; Pennington, T H; Pennington, C I; Reiss, H; Loudon, I (October 1994). "Letters". BMJ. 309 (6959): 952. doi:10.1136/bmj.309.6959.952. PMC 2541124. PMID 7950672.

- ^ Groner M.D., Johnathan (2008). "The Hippocratic Paradox: The Role of The Medical Profession In Capital Punishment In The United States". Fordham Urban Law Journal Library.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Nutton, Vivian (2004). Ancient Medicine. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Notes

- The Hippocratic Oath – an article by The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (h2g2).

- The Hippocratic Oath Today: Meaningless Relic or Invaluable Moral Guide? – a PBS NOVA online discussion with responses from doctors as well as 2 versions of the oath. pbs.org

- Lewis Richard Farnell, Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality, 1921.

- "Codes of Ethics: Some History" by Robert Baker, Union College in Perspectives on the Professions, Vol. 19, No. 1, Fall 1999, ethics.iit.edu

External links

- Hippocratic Oath, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (h2g2).

- Hippocratic Oath – Classical version, pbs.org

- Hippocratic Oath – Modern version, pbs.org

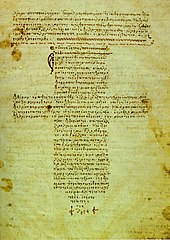

- Hippocratis jusiurandum – Image of a 1595 copy of the Hippocratic oath with side-by-side original Greek and Latin translation, bium.univ-paris5.fr

- Hippocrates | The Oath – National Institutes of Health page about the Hippocratic oath, nlm.nih.gov

- Tishchenko P. D. Resurrection of the Hippocratic Oath in Russia, zpu-journal.ru