Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

From left to right: Sergey Aksyonov, Vladimir Konstantinov, Vladimir Putin, and Alexei Chaly sign the "Restitution of Crimea and Sevastopol inside the Russian Federation" treaty on 18 March 2014 | |

| Date | 18–21 March 2014 (Treaty signing to ratification) |

|---|---|

| Location | Crimean Peninsula Moscow, Russia |

| Also known as | Annexation of Crimea by Russia[1] Accession of Crimea to the Russian Federation[2] |

| Participants | |

| Outcome |

|

| Accession treaty ratified | 21 March 2014 |

| Finalization | 1 January 2015 |

| Status | Disputed by Ukraine; not recognized by the majority of the United Nations members |

The internationally recognised Ukrainian territory of Crimea, consisting of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, was annexed by the Russian Federation in March 2014. From the time of the annexation on 21 March 2014, Russia has de facto administered the territory as two federal subjects—the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol[3]—within the Crimean Federal District.

The annexation took place in the aftermath of the 2014 Crimean crisis as the result of military intervention by Russia into the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, both of which had been administrative divisions of Ukraine. Masked green troops without insignia, identified as the Russian military by multiple worldwide sources, took over the Supreme Council of Crimea,[4][5] which led to the installation of the pro-Russian Aksyonov government in Crimea, the declaration of Crimea's independence and the holding of a disputed, unconstitutional referendum, that was described by BBC News reporter John Simpson as a "remarkable, quick and mostly bloodless coup d'état".[6]

The event caused much controversy and was condemned by many world leaders, as well as NATO, as an illegal annexation of Ukrainian territory, in disrespect to the signing of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum on its sovereignty and territorial integrity, by Russia.[7] It led to the other members of the then G8 deciding to expel Russia from the group, thereby returning it to the previous G7, then introducing the first round of sanctions against the country.[citation needed] Moreover, the Yatsenyuk Government, responsible for internal Ukrainian affairs at the time, confirmed at least seven constitutional violations of the process, including the dodged obligation of Crimea to request such restitution from Ukraine itself first, before being given the formal right to conduct any supra-political processes for the matter.

Russia opposes the "annexation" label,[8] with Putin defending the referendum saying it complied with international law.[9] Ukraine disputes this, as it does not recognize the independence of the Republic of Crimea or the accession itself as legitimate.[10] The United Nations General Assembly also rejected the vote and annexation, adopting a non-binding resolution affirming the "territorial integrity of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders".[11][12]

Background

From 1783, Crimea was a part of the Russian Empire, incorporated into it as [[{{{1}}}]]. In 1795, Crimea was merged into Novorossiysk Governorate, and in 1803, it was again separated from it into Taurida Governorate. A series of short-lived governments (Crimean People's Republic, Crimean Regional Government, Crimean SSR) were established during first stages of the Russian Civil War, but they were followed by White Russian (General Command of the Armed Forces of South Russia, later South Russian Government) and, finally, Soviet (Crimean ASSR) incorporations of Crimea into their own states. After World War II and the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, the Crimean ASSR was stripped of its autonomy in 1946 and was downgraded to the status of an oblast.

In 1954, the Crimean Oblast was transferred from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR by decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. However, it was unclear whether the transfer affected the peninsula's largest city of Sevastopol, which enjoyed a special status in the postwar Soviet Union,[13] and in 1993, the Supreme Soviet of Russia claimed Sevastopol was part of Russia,[14] resulting in a territorial dispute with Ukraine.[15]

In 1989, under perestroika, the Supreme Soviet declared the deportation of the Crimean Tatars under Stalin had been illegal,[16] and the mostly Muslim ethnic group was allowed to return to Crimea.[17]

In 1990, the Crimean Oblast Soviet proposed the restoration of the Crimean ASSR.[18] The oblast conducted a referendum in 1991, which asked whether Crimea should be elevated into a signatory of the New Union Treaty (that is, became a union republic on its own). By that time, though, the dissolution of the Soviet Union was well underway. The Crimean ASSR was restored for less than a year as part of Soviet Ukraine before Ukrainian independence. Newly independent Ukraine maintained Crimea's autonomous status,[19] while the Supreme Council of Crimea affirmed the peninsula's "state sovereignty".[20][21]

On 21 May 1992, the Supreme Soviet of Russia adopted a resolution, which declared Crimea's 1954 transfer invalid and called for trilateral negotiations on the peninsula's status. Confrontation between the president and parliament of Russia, which later erupted into armed conflict in Moscow, prevented this declaration from having any actual effect in Crimea or Ukraine.[22]

From 1992 to 1994, various pro-Russian political movements attempted to separate Crimea from Ukraine. The 1994 regional elections represented a high point for pro-Russian political factions in Crimea.[23] But the elections came at a difficult time for Crimeans who wanted to rejoin Russia, as the Russian government was engaged in a rapprochement with the Western world and the Ukrainian government was determined to safeguard its sovereignty. These factors enabled Ukrainian authorities to abolish the Crimean presidency and constitution by 1995,[24][25] without any meaningful interference or protest from Ukraine's eastern neighbor. Afterwards, pro-Russian movements largely waned, and in 1998, the separatists lost the Crimean Supreme Council election.[23]

During the 2000s, as tensions between Russia and several of its neighbors rose, the likelihood of Russian-Ukrainian conflict around Crimea increased. A Council on Foreign Relations report released in 2009 outlined a scenario under which Russia could intervene in Crimea to protect "Russian compatriots", potentially with the backing of Crimean Tatars.[26]

Euromaidan and 2014 Ukrainian revolution

The Euromaidan movement began in late November 2013 with protests in Kiev against President Viktor Yanukovych, who won election in 2010 with strong support in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and southern and eastern Ukraine. The Crimean government strongly supported Yanukovych and condemned the protests, saying they were "threatening political stability in the country". The Supreme Council of Crimea supported the government's decision to suspend negotiations on the pending Ukraine-EU Association Agreement and urged Crimeans to "strengthen friendly ties with Russian regions".[27][28][29]

On 4 February 2014, the Presidium of the Supreme Council considered holding a referendum on the peninsula's status and asking the government of Russia to guarantee the vote.[30] The Security Service of Ukraine responded by opening a criminal case to investigate the possible "subversion" of Ukraine's territorial integrity.[31]

The Euromaidan protests reached a fever pitch in February 2014, and Yanukovych and many of his ministers fled the capital. After opposition factions and defectors from Yanukovych's Party of Regions cobbled together a parliamentary quorum in the Verkhovna Rada, the national legislature voted on 22 February to remove Viktor Yanukovich from his post on the grounds that he was unable to fulfill his duties,[32] although the legislative removal lacked the required three quarter vote of sitting MPs according to the constitution in effect at the time, which the Rada also voted to nullify.[33][34][35] This move was regarded as a coup d'état by many within Ukraine and Russia,[36] although it was widely recognized internationally.[37]

Change of regional government and Russian intervention

The revolution against Yanukovich triggered a political crisis in Crimea, which started as demonstrations against new central authorities, but rapidly escalated due to Russia's overt support for separatist political factions.

On 27 February, unidentified troops widely suspected of being Russian commandos seized the building of the Supreme Council of Crimea (the regional parliament) and the building of the Council of Ministers in Simferopol.[39][40] Russian flags were raised over these buildings,[41] and barricades were erected outside them.[42] With the unidentified troops still occupying the government building in Simferopol, the Supreme Council of Crimea dissolved the old Council of Ministers of Crimea and designated Sergey Aksyonov, leader of the minority Russian Unity party, to be Crimea's new prime minister. This appointment was declared illegal by Ukraine's new interim government.[43] Both Aksyonov and speaker Vladimir Konstantinov stated that they viewed Viktor Yanukovich as the de jure president of Ukraine, through whom they were able to ask Russia for assistance.[44] On the same day, more troops in unmarked uniforms, assisted this time by Crimean riot police known as Berkut, established security checkpoints on the Isthmus of Perekop and the Chonhar Peninsula, which separate Crimea from the Ukrainian mainland.[42][45][46][47][48] Within hours, Ukraine had effectively been cut off from Crimea.

On 1 March 2014, Aksyonov declared Crimea's new de facto authorities would exercise control of all Ukrainian military installations on the peninsula. He also asked Russian President Vladimir Putin, who had been Yanukovych's primary international backer and guarantor, for "assistance in ensuring peace and public order" in Crimea.[50] Putin promptly received authorization from the Federation Council of Russia for a Russian military intervention in Ukraine "until normalization of a socio-political environment in the country".[51][52] Putin's swift maneuver prompted protests of intelligentsia and demonstrations in Moscow against a Russian military campaign in Crimea. By 2 March, Russian troops moving from the country's naval base in Sevastopol and reinforced by troops, armor, and helicopters from mainland Russia exercised complete control over the Crimean Peninsula.[53][54][55] Russian troops operated in Crimea without insignia. Despite numerous media reports and statements by the Ukrainian and foreign governments describing the unmarked troops as Russian soldiers, government officials concealed the identity of their forces, claiming they were local "self-defense" units over whom they had no authority.[56] As late as 17 April, Russian foreign minister Lavrov claimed that there are no spare armed forces in the territory of Crimea.[57]

Russian officials eventually admitted to their troops' presence. On 17 April 2014, Putin acknowledged the Russian military backed Crimean separatist militias, stating that Russia's intervention was necessary "to ensure proper conditions for the people of Crimea to be able to freely express their will".[58] Defense Minister Sergey Shoygu said the country's military actions in Crimea were undertaken by forces of the Black Sea Fleet and were justified by "threat to lives of Crimean civilians" and danger of "takeover of Russian military infrastructure by extremists".[59] Ukraine complained that by increasing its troop presence in Crimea, Russia violated the agreement under which it headquartered its Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol[60] and violated the country's sovereignty.[61] The United States and United Kingdom also accused Russia of breaking the terms of the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances, by which Russia, the U.S., and the UK had reaffirmed their obligation to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine.[62] The Russian government said the Budapest Memorandum did not apply due to "complicated internal processes" in Crimea.[63][64]

Legal obstacles to Crimea annexation

According to the Constitution of Russia, the admission of new federal subjects is governed by federal constitutional law (art. 65.2).[65] Such a law was adopted in 2001, and it postulates that admission of a foreign state or its part into Russia shall be based on a mutual accord between the Russian Federation and the relevant state and shall take place pursuant to an international treaty between the two countries; moreover, it must be initiated by the state in question, not by its subdivision or by Russia.[66] This law would have seemed to require that Ukraine initiate any negotiations involving a Crimean annexation by Russia.

On 28 February 2014, Russian MP Sergey Mironov, along with certain other members of the Duma, introduced a bill to alter Russia's procedure for adding federal subjects. According to the bill, accession could be initiated by a subdivision of a country, provided that there is "absence of efficient sovereign state government in foreign state"; the request could be made either by subdivision bodies on their own or on the basis of a referendum held in the subdivision in accordance with corresponding national legislation.[67] The Venice Commission stated that the bill violated "in particular, the principles of territorial integrity, national sovereignty, non-intervention in the internal affairs of another state and pacta sunt servanda" and was therefore incompatible with international law.[68]

On 11 March 2014, both the Supreme Council of Crimea and the Sevastopol City Council adopted a declaration of independence, which stated their intent to declare independence and request full accession to Russia in case the pro-Russian answer received the most votes during the scheduled status referendum. The declaration directly referred to the Kosovo independence precedent, by which the Albanian-populated Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija declared independence from Russia's ally Serbia as the Republic of Kosovo in 2008—a unilateral action Russia staunchly opposed. Many analysts saw the Crimean declaration as an overt effort to pave the way for Crimea's annexation by Russia.[69]

Crimean authorities' stated plans to declare independence from Ukraine made the Mironov bill unnecessary. On 20 March 2014, two days after the treaty of accession was signed, the bill was withdrawn by its initiators.[70]

Crimean status referendum

On 27 February, following the takeover of its building, the Supreme Council of Crimea voted to hold a referendum on 25 May, with the initial question as to whether Crimea should upgrade its autonomy within Ukraine.[71] The referendum date was later moved from 25 May to 30 March.[72] A Ukrainian court declared the referendum to be illegal.[73]

On 4 March, Russian President Vladimir Putin claimed Russia was not considering annexing Crimea. He said of the peninsula that "only citizens themselves, in conditions of free expression of will and their security can determine their future".[74] Putin later acknowledged that in early March there were "secret opinion polls" held in Crimea, which, according to him, reported overwhelming popular support for Crimea's incorporation into Russia.[75]

On 6 March, the Supreme Council moved the referendum date to 16 March and changed its scope to ask a new question: whether Crimea should accede to Russia or restore the 1992 constitution within Ukraine, which the Ukrainian government had previously invalidated. This referendum, unlike one announced earlier, contained no option to maintain the status quo of governance under the 1998 constitution.[76]

On 14 March, the Crimean status referendum was deemed unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine,[77] and a day later, the Verkhovna Rada formally dissolved the Crimean parliament.[78]

The referendum was held despite the opposition from Kiev. Official results reported about 95% of participating voters in Crimea and Sevastopol were in favor of joining Russia.[79] The results of referendum are questioned,[80] Another report by Evgeny Bobrov, a member of the Russian President's Human Rights Council, suggested the official results were inflated and only 15% to 30% of Crimeans actually voted for the Russian option.[81][82][83]

The means by which the referendum was conducted were widely criticized by foreign governments and in the Ukrainian and international press, with reports that anyone holding a Russian passport regardless of residency in Crimea was allowed to vote. However, Russia defended the integrity of the voting process, and a group of European observers, principally from right-wing and far-right political parties aligned with Putin, said the referendum was conducted in a free and fair manner.[84][85][86]

Breakaway republic

On 17 March, following the official announcement of the referendum results, the Supreme Council of Crimea declared the formal independence of the Republic of Crimea, comprising the territories of both the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, which was granted special status within the breakaway republic.[87] The Crimean parliament declared the "partial repeal" of Ukrainian laws and began nationalizing private and Ukrainian state property located on the Crimean Peninsula, including Ukrainian ports[88] and property of Chornomornaftogaz.[89] Parliament also formally requested that the Russian government admit the breakaway republic into Russia.[90] On same day, the de facto Supreme Council renamed itself the Crimean State Council,[91] declared the Russian ruble an official currency alongside the hryvnia,[92] and announced that Crimea would switch to Moscow Time (UTC+4) on 30 March.[93]

Putin officially recognized the Republic of Crimea by decree[94] and approved the admission of Crimea and Sevastopol as federal subjects of Russia.[95]

Accession treaty and immediate aftermath

The Treaty on Accession of the Republic of Crimea to Russia was signed between representatives of the Republic of Crimea (including Sevastopol, with which the rest of Crimea briefly unified) and the Russian Federation on 18 March 2014 to lay out terms for the immediate admission of the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol as federal subjects of Russia and part of the Russian Federation.[96][97] It was ratified by the Federal Assembly by March 21.[98]

On 19 March Putin submitted to the State Duma, the lower house of parliament, a treaty of Crimea's reunification with Russia and a constitutional amendment on setting up two new constituent territories of the Russian Federation.[99] Russian Constitutional Court found that treaty is in compliance with Constitution of Russia. The court sat in an emergency session following a formal request by President Vladimir Putin to assess the constitutionality of the treaty.[100][101]

After the Russian Constitutional Court upheld the constitutionality of the treaty, the State Duma ratified it on 20 March.[102][103] The Duma also approved the draft federal constitutional law admitting Crimea and Sevastopol and establishing them as federal subjects.[104][105] A Just Russia's Ilya Ponomarev was the only State Duma member to vote against the measures. A day later, the treaty itself and the required amendment to article 65 of the Russian Constitution (which lists the federal subjects of Russia) were ratified by the Federation Council[106] and almost immediately signed into law by Putin.[107] Crimea's admission to the Russian Federation was considered retroactive to 18 March, when Putin and Crimean leaders signed the draft treaty.[108]

On 24 March, Ukraine ordered the full withdrawal of all of its armed forces from Crimea.[109] The Ukrainian Ministry of Defense reported about half of Ukraine's troops in Crimea defected to Russia.[110][111]

On 27 March, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a non-binding resolution, which declared the Crimean referendum and subsequent status change invalid, by a vote of 100 to 11, with 58 abstentions and 24 absent.[112][113]

Crimea and Sevastopol switched to Moscow Time at the end of March.[114][115]

On 2 April, Russia formally denounced the 2010 Kharkiv Pact and Partition Treaty on the Status and Conditions of the Black Sea Fleet.[116] Putin cited "the accession of the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol into Russia" and resulting "practical end of renting relationships" as his reason for the denunciation.[117] On the same day, he signed a decree formally rehabilitating the Crimean Tatars, who were ousted from their lands in 1944, and the Armenian, German, Greek, and Bulgarian minority communities in the region that Stalin also ordered removed in the 1940s.

On 11 April, the Constitution of the Republic of Crimea and City Charter of Sevastopol were adopted,[118] and on same day, the new federal subjects were enumerated in a newly published revision of the Russian Constitution.[119]

Transition and aftermath

The number of tourists visiting Crimea in the 2014 season is expected to be lower than in the previous years due to worries about the political situation.[120] The Crimean government members hope that Russian tourists will flow in.[121] The Russian government is planning to promote Crimea as a resort and provide subsidized holidays to the peninsula for children and state workers.[122]

The Sofia news agency Novinite claims that according to the German newspaper Die Welt, the annexation of Crimea is economically disadvantageous for the Russian Federation. Russia will have to spend billions of euros a year to pay salaries and pensions. Moreover, Russia will have to undertake costly projects to connect Crimea to the Russian water supply and power system because Crimea has no land connection to Russia and at present gets water, gas and electricity from mainland Ukraine. This will require building a bridge and a pipeline across the Kerch Strait. Also, Novinite claims that a Ukrainian expert told Die Welt that Crimea "will not be able to attract tourists".[123]

The Russian business newspaper Kommersant expresses an opinion that Russia will not acquire anything economically from "accessing" Crimea, which is not very developed industrially, having just a few big factories, and whose yearly gross product is only $4 billion. The newspaper also says that everything from Russia will have to be delivered by sea, higher costs of transportation will result in higher prices for everything, and in order to avoid a decline in living standards Russia will have to subsidize Crimean people for a few months. In total, Kommersant estimates the costs of integrating Crimea into Russia in $30 billion over the next decade, i.e. $3 billion per year.[124]

On the other hand western oil experts estimate that Russia's seizing of Crimea, and the associated control of an area of Black Sea more than three times its land area gives it access to oil and gas reserves potentially worth trillions of dollars. It also deprives Ukraine of its chances of energy independence. Most immediately however, analysts say, Moscow's acquisition may alter the route along which the South Stream pipeline would be built, saving Russia money, time and engineering challenges. It would also allow Russia to avoid building in Turkish territorial waters, which was necessary in the original route in order to avoid Ukrainian territory.[125][126]

Russian/Chechen businessman Ruslan Baisarov announced he is ready to invest 12 billion rubles into the construction of a modern sea resort in Crimea, which is expected to create about 1,300 jobs. Ramzan Kadyrov, the Head of Chechnya, said that other Chechen businessmen are planning to invest into Crimea as well.[127]

The Russian Federal Service for Communications (Roskomnadzor) warned about a transition period as Russian operators have to change the numbering capacity and subscribers. Country code will be replaced from the Ukrainian +380 to Russian +7. Codes in Crimea start with 65, but in the area of "7" the 6 is given to Kazakhstan which shares former Soviet Union +7 with Russia, so city codes have to change. The regulator assigned 869 dialing code to Sevastopol and the rest of the peninsula received a 365 code.[128] At the time of the unification with Russia, telephone operators and Internet service providers in Crimea and Sevastopol are connected to the outside world through the territory of Ukraine.[129] Minister of Communications of Russia, Nikolai Nikiforov announced on his Twitter account that postal codes in Crimea will now have six-figures: to the existing five-digit number the number two will be added at the beginning. For example, the Simferopol postal code 95000 will become 295000.[130]

Regarding Crimea's borders, the head of Russian Federal Agency for the Development of the State Border Facilities (Rosgranitsa) Konstantin Busygin, who was speaking at a meeting led by Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin in Simferopol, the capital of Crimea said the Russian state border in the north of Crimea which, according to his claims, now forms part of the Russian-Ukrainian border, will be fully equipped with necessary facilities.[131] In the area that now forms the border between Crimea and Ukraine mining the salt lake inlets from the sea that constitute the natural borders, and in the spit of land left over stretches of no-man's-land with wire on either side was created.[132] On early June that year Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev signed a Government resolution №961[133] dated 5 June 2014 establishing air, sea, road and railway checkpoints. The adopted decisions create a legal basis for the functioning of a checkpoint system at the Russian state border in the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol.[134]

In the year following the annexation, armed men seized various Crimean businesses, including banks, hotels, shipyards, farms, gas stations, a bakery, a dairy, and Yalta Film Studio.[135][136][137]

Human rights situation

On 9 May 2014 the new "anti-extremist" amendment to the Criminal Code of Russia, passed in December 2013, came into force. Article 280.1 designated incitement of violation of territorial integrity of the Russian Federation[138] (incl. calls for secession of Crimea from Russia[139]) as a criminal offence in Russia, punishable by a fine of 300 thousand roubles or imprisonment up to 3 years. If such statements are made in public media or the internet, the punishment could be obligatory works up to 480 hours or imprisonment up to five years.[138]

Following the annexation of Crimea, according to report released on the Russian government run President of Russia's Council on Civil Society and Human Rights website, Tatars who were opposed to Russian rule have been persecuted, Russian law restricting freedom of speech has been imposed, and the new pro-Russian authorities "liquidated" the Kiev Patriarchate Orthodox church on the peninsula.[82]

After the annexation, on May 16 the new Russian authorities of Crimea issued a ban on the annual commemorations of the anniversary of the Deportation of the Crimean Tatars by Stalin in 1944, citing "possibility of provocation by extremists" as a reason.[140] Previously, when Crimea was controlled by Ukraine, these commemorations had taken place every year.The pro-Russian Crimean authorities also banned Mustafa Jemilev, a human rights activist, Soviet dissent, member of the Ukrainian parliament, and former Chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatars from entering Crimea.[141] Additionally, Mejlis reported, that officers of Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB) raided Tatar homes in the same week, on the pretense of "suspicion of terrorist activity".[142] The Tatar community eventually did hold commemorative rallies in defiance of the ban.[141][142] In response Russian authorities flew helicopters over the rallies in an attempt to disrupt them.[143]

Ukrainian response

Immediately after the treaty of accession was signed in March, the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs summoned the Provisional Principal of Russia in Ukraine to present note verbale of protest against Russia's recognition of the Republic of Crimea and its subsequent annexation.[144] Two days later, the Verkhovna Rada condemned the treaty[145] and called Russia's actions "a gross violation of international law". The Rada called on the international community to avoid recognition of the "so-called Republic of Crimea" or the annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol by Russia as new federal subjects.

On 15 April 2014, the Verkhovna Rada declared the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol to be under "provisional occupation" by the Russian military.[146] The territories were also deemed "inalienable parts of Ukraine" subject to Ukrainian law. Among other things, the special law approved by the Rada restricted foreign citizens' movements to and from the Crimean Peninsula and forbade certain types of entrepreneurship.[147] The law also forbade activity of government bodies formed in violation of Ukrainian law and designated their acts as null and void. The voting rights of Crimea in national Ukrainian elections were also suspended.[148] The law had little to no actual effect in Crimea itself due to the mutual non-recognition between Kiev and Simferopol.

International response

United Nations Resolutions

Security Council Resolution

On 15 March 2014 a U.S.-sponsored resolution was put forward to vote in the UN Security Council to reaffirm council's commitment to Ukraine's "sovereignty, independence, unity and territorial integrity." A total of 13 council members voted in favour of the resolution, China abstained, while Russia vetoed the U.N. resolution declaring Crimean referendum, 2014, on the future of Crimean Peninsula, as illegal.[149]

General Assembly Resolution

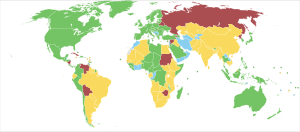

On 27 March 2014, The UN General Assembly approved a resolution[150] describing the referendum leading to annexation of Crimea by Russia as illegal. The draft resolution, which was titled 'Territorial integrity of Ukraine' was co-sponsored by Canada, Costa Rica, Germany, Lithuania, Poland, Ukraine and the US. It affirmed council's commitment to the "sovereignty, political independence, unity and territorial integrity of Ukraine within its internationally recognised borders." The resolution tried to underscore that the March 16 referendum held in Crimea and the city of Sevastopol has no validity and cannot form the basis for any alteration of the status of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea or of the city of Sevastopol. The resolution got 100 votes in its favor, while 11 nations voted against and 58 countries abstained from the vote. The resolution was non-binding and the vote was largely symbolic.[151]

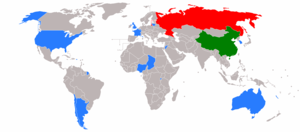

Recognition

The vast majority of the international community has not recognized the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol as part of Russia. Most nations located in North America, Central America, Europe, Oceania, Africa, as well as non-former-Soviet-Union Asia have openly rejected the referendum and the accession, and instead consider Crimea and Sevastopol to be administrative divisions of Ukraine. The remainder have largely remained neutral. The vote on United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262 (supporting the position that Crimea and Sevastopol remain part of Ukraine) was 100 to 11 in favor, with 58 states abstaining and a further 24 of the 193 member states not voting through being absent when the vote took place. The 100 states voting in favor represented about 34% of the world's population, the 11 against represented about 4.5%, the 58 abstentions represented about 58%, and the 24 absents represented about 3.5%.

Several members of the United Nations have made statements about their recognition of the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol as federal subjects of Russia:

The position of Belarus is vague: it includes statements made by Alexander Lukashenko that "Ukraine should remain an integral, indivisible, non-aligned state" and "As for Crimea, I do not like it when the integrity and independence of a country are broken", on the one hand, and "Today Crimea is part of the Russian Federation. No matter whether you recognize it or not, the fact remains." and "Whether Crimea will be recognized as a region of the Russian Federation de-jure does not really matter", on the other hand.[158]

Three non-UN member states recognized the results of the referendum: Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Nagorno-Karabakh. A fourth, Transnistria, sent a request on 18 March 2014 to join the Russian Federation following the Crimean example and in compliance with the Admission Law provisions.[159][160][161] On 16 April 2014 Transnistria urged Russia and the United Nations to recognize its independence.[162] Putin is aware of Transnistria's recognition request, according to Dmitry Peskov.[163]

Commentary

German Federal Minister of Finance Wolfgang Schäuble, Chancellor Angela Merkel and Minister of Foreign Affairs Frank-Walter Steinmeier all stated, that such comparisons are unacceptable.[164] However Chancellor Merkel also said "The so-called referendum…, the declaration of independence …, and the absorption into the Russian Federation (were), in our firm opinion,…against international law"[165] and that it was "shameful" for Russia to compare the independence of Kosovo with the referendum for independence in Crimea.[166]

British prime minister David Cameron said "No amount of sham and perverse democratic process or skewed historical references can make up for the fact that this is an incursion into a sovereign state and a land grab of part of its territory with no respect for the law of that country or for international law."[167]

President Obama commented, "the Crimean 'referendum,' which violates the Ukrainian constitution and occurred under duress of Russian military intervention, would never be recognized by the United States and the international community."[168]

The European Council and the European Commission made the joint statement "The European Union does neither recognise the illegal and illegitimate referendum in Crimea nor its outcome."[169]

Czech President Miloš Zeman said: "Even though I understand the interests of Crimea’s Russian-speaking majority, which was annexed to Ukraine by Khrushchev, we have our experience with the 1968 Russian military invasion."[170] Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves stated that the annexation was "done too quickly and professionally not to have been planned far in advance" and said that the failure of the Budapest Memorandum "may have far-reaching implications for generations. I don’t know what country in the future would ever give up its nuclear weapons in exchange for a security guarantee."[171]

Former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev has defended the referendum that led to Crimea's annexation by Russia: "While Crimea had previously been joined to Ukraine [in 1954] based on the Soviet laws, which means [Communist] party laws, without asking the people, now the people themselves have decided to correct that mistake."[172]

Sanctions

Sanctions were imposed to prevent number of Russian and Crimean officials and politicians to travel to Canada, the United States, and the European Union.

Japan announced milder sanctions than the US and EU. These include suspension of talks relating to military, space, investment, and visa requirements.[174]

Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaitė praised the U.S.'s decision to sanction Russia, saying Obama had set an example.[175]

In response to the sanctions introduced by the U.S. and EU, the Russian Duma unanimously passed a resolution asking for all members of the Duma to be included on the sanctions list.[176] Head of the opposition A Just Russia party Sergei Mironov said he was proud of being included on the sanctions list, "It is with pride that I have found myself on the black list, this means they have noticed my stance on Crimea."[176]

Three days after the lists were published, the Russian Foreign Ministry published a reciprocal sanctions list of US citizens, which consisted of 10 names, including House of Representatives Speaker John Boehner, Senator John McCain, and two advisers to President Obama.[177] Several of those sanctioned responded with pride at their inclusion on the list, including John Boehner who, through his spokesperson Michael Steel, said, "The Speaker is proud to be included on a list of those willing to stand against Putin's aggression.";[178][179] John McCain who tweeted, "I'm proud to be sanctioned by Putin - I'll never cease my efforts & dedication to freedom & independence of Ukraine, which includes Crimea.";[175][178][179] Bob Menendez;[178][179] Dan Coats;[175][178][179][180] Mary Landrieu[180] and Harry Reid.[180]

According to the Financial Times on Friday, 21 March 2014, "As recently as the start of the week, some of Moscow's financial elite were blasé about the prospect of sanctions. But Russia's businessmen were no longer smiling by [… the end of it] after expanded US sanctions rippled through financial markets hitting the business interests of some of the country's richest people."[181] The Americans centered on the heart of Moscow's leadership,[182] though the EU initial list shied from targeting Putin's inner circle.[183] As ratings agencies Fitch and Standard & Poor's downgraded Russian credit outlook,[184] Novatek, Russian second-largest gas producer, saw $2.5bn in market value wiped out when its shares sank by nearly 10%, rendering Putin's close friend Gennady Timchenko, who has a 23% stake in the company, $575m poorer.[181] "I do hope that there is some serious diplomatic activity going on behind the scenes," said one Russian banker quoted by the newspaper,[185] though others were more sanguine on the question of whether the sanctions would have any enduring effect[184]—"What has been announced so far is really nothing. It's purely cosmetic," said a French banker based in Moscow[186]—and Russians, top and bottom, seemed defiant.[187] The official Russian response was mixed.[188]

Cartographic response

- National Geographic Society stated, that their policy is "to portray current reality" and "Crimea, if it is formally annexed by Russia, would be shaded gray", but also further remarked that this step does not suggest recognizing legitimacy of such.[189] As of April 2014 Crimea is still displayed as part of Ukraine.[190]

- Google Maps will paint Crimea as disputed territory for most of visitors.[190] For Russian and Ukrainian versions of website Crimea will be marked as belonging to corresponding country (Russia or Ukraine respectively).[190][191] Google stated, that it "work with sources to get the best interpretation of the border or claim lines".[192]

- Yandex Maps displays Crimea according to official position of user's country. Users visiting Yandex.ru from Russia will see Crimea displayed as Russian territory, users visiting yandex.ua from Ukraine will see Crimea as Ukrainian and all other users (from other countries) will see Crimea as Russian territory.[190] According to official statement, the company works with users from different countries and "displays reality that surrounds them".[193]

- Bing Maps,[194] OpenStreetMap and HERE display Crimea as belonging to Ukraine.[190] In particular, Open Street Map requested its users to refrain from editing borders and administrative relations of subdivisions located in Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol until 31 May 2014.[190] On 5 June 2014 OpenStreetMap switched to a territorial dispute option, displaying Crimea as a disputed territory belonging to both countries.[195]

- Mail.Ru maps display Crimea as part of Russia[190][196]

See also

References

- ^ "Crimea Switches To Moscow Time". The Huffington Post.

- ^ "Russia takes Crimea back". English pravda.ru.

- ^ "Putin signs laws on reunification of Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol with Russia". ITAR TASS. March 21, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ "Putin's Man in Crimea Is Ukraine's Worst Nightmare". Time.

Before dawn on Feb. 27, at least two dozen heavily armed men stormed the Crimean parliament building and the nearby headquarters of the regional government, bringing with them a cache of assault rifles and rocket propelled grenades. A few hours later, Aksyonov walked into the parliament and, after a brief round of talks with the gunmen, began to gather a quorum of the chamber's lawmakers.

- ^ "RPT-INSIGHT-How the separatists delivered Crimea to Moscow". Reuters. March 13, 2014.

Only a week after gunmen planted the Russian flag on the local parliament, Aksyonov and his allies held another vote and declared parliament was appealing to Putin to annex Crimea

- ^ "BBC News - Russia's Crimea plan detailed, secret and successful". BBC News.

- ^ "NATO Secretary-General: Russia's Annexation of Crimea Is Illegal and Illegitimate". Brookings. March 19, 2014.

- ^ Лавров назвал оскорбительными заявления Запада об аннексии Крыма. vz.ru (in Russian). March 21, 2014.

- ^ Crimeans vote over 90 percent to quit Ukraine for Russia Reuters, 16 March 2014

- ^ Oleksandr Turchynov (March 20, 2014). "Декларація "Про боротьбу за звільнення України" (Declaration "Of the Struggle for the Liberation of Ukraine")" (in Ukrainian). Parliament of Ukraine. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ UN General Assembly adopts resolution affirming Ukraine's territorial integrity, China Central Television (28 March 2014)

- ^ "United Nations A/RES/68/262 General Assembly" (PDF). United Nations. April 1, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ See, for example, Fedorov, A. V. (1997). "3.2: Правовой статус Севастополя в составе РСФСР". Правовой статус Крыма. Правовой статус Севастополя (in Russian). Moscow: Moscow State University Publishing.

- ^ Севастополь: вчера и сегодня в документах. Обозреватель - Observer (in Russian). RAU Corporation. 1993.

- ^ Losev, Igor (September 19, 2008). "Сверхнаглость" сработает? Севастополь: псевдоюридические аргументы Ю.М.Лужкова. day.kiev.ua (in Russian).

- ^ Декларация Верховного Совета СССР "О признании незаконными и преступными репрессивных актов против народов, подвергшихся насильственному переселению, и обеспечении их прав" (in Russian). 1989.

- ^ "The Crimean Tatars began repatriating on a massive scale beginning in the late 1980s and continuing into the early 1990s. The population of Crimean Tatars in Crimea rapidly reached 250,000 and leveled off at 270,000 where it remains as of this writing [2001]. There are believed to be between 30,000 and 100,000 remaining in places of former exile in Central Asia." Greta Lynn Uehling, The Crimean Tatars (Encyclopedia of the Minorities, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn) iccrimea.org

- ^ ДЕКЛАРАЦИЯ О ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОМ И ПРАВОВОМ СТАТУСЕ КРЫМА (in Russian). 1990.

- ^ "Про внесення змін і доповнень до Конституції... від 19.06.1991 № 1213а-XII" (in Ukrainian). June 19, 1991.

- ^ Parliament of Ukraine (November 17, 1994). Декларация о государственном суверенитете Крыма (in Russian). Government of Ukraine. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ Parliament of Ukraine (October 20, 1999). О Республике Крым как официальном названии демократического государства Крым (in Russian). Government of Ukraine. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ Gamov, Alexander (March 12, 2014). "Руслан Хасбулатов – "КП": Передайте Обаме – Крым и Севастополь могли войти в Россию ещё 20 лет назад! // KP.RU". kp.ru (in Russian).

- ^ a b Полунов, Александр Юрьевич. Общественные организации русского Крыма: политическая деятельность, стратегии взаимоотношений с властью. Государственное управление. Выпуск № 21. Декабрь 2009 года. Template:Ru icon

- ^ Про внесення змін і доповнень до Конституції (Основного Закону) України. Верховна Рада України; Закон від 21.09.1994 № 171/94-ВР Template:Uk icon

- ^ Про скасування Конституції і деяких законів Автономної Республіки Крим Верховна Рада України; Закон від 17.03.1995 № 92/95-ВР (in Ukrainian). March 18, 1995.

- ^ Pifer, Steven (July 2009). "Crisis Between Ukraine and Russia" (PDF). Center for Preventive Action of the Council on Foreign Affairs.

- ^ Крымский парламент решил ещё раз поддержать Азарова и заклеймить оппозицию – Европейская правда, 27 ноября 2013

- ^ Решение ВР АРК от 27.11.2013 № 1477-6/13 "О политической ситуации". rada.crimea.ua (in Russian). November 27, 2013.

- ^ Заявление ВР АРК от 22.01.2014 № 29-6/14-ВР "О политической ситуации". rada.crimea.ua (in Russian). January 22, 2014.

- ^ Защитить статус и полномочия Крыма! (in Russian). Supreme Council of Crimea. February 4, 2014.

- ^ "Крымские татары готовы дать отпор попыткам отторжения автономии от Украины – Чубаров". Unian.net. February 16, 2014. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- ^ "Archrival Is Freed as Ukraine Leader Flees". The New York Times. February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ John Feffer (March 14, 2014). "Who Are These 'People,' Anyway?". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ "Rada removes Yanukovych from office, schedules new elections for May 25". Interfax-Ukraine. February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ Sindelar, Daisy (February 23, 2014). "Was Yanukovych's Ouster Constitutional?". Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberty (Rferl.org). Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ "Lavrov: If West accepts coup-appointed Kiev govt, it must accept a Russian Crimea — RT News". Rt.com. March 30, 2014. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine MPs appoint interim president as Yanukovych allies dismissed – 23 February as it happened". The Guardian. February 23, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ^ Maria Tsvetkova; Jason Bush (March 15, 2014). "UPDATE 1-Ukraine crisis triggers Russia's biggest anti-Putin protest in two years". Reuters. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Andrew Higgins; Steven Erlanger (February 27, 2014). "Gunmen Seize Government Buildings in Crimea". New York Times. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ "Lessons identified in Crimea – does Estonia's national defence model meet our needs?". Estonian World. May 5, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ^ Gumuchian, Marie-Louise; Smith-Spark, Laura; Formanek, Ingrid (February 27, 2014). "Gunmen seize government buildings in Ukraine's Crimea, raise Russian flag". CNN.

- ^ a b "Lenta.ru: Бывший СССР: Украина: Украинский депутат объявил о бунте крымского "Беркута"".

- ^ Турчинов издал указ о незаконности избрания нового премьера Крыма (in Ukrainian). March 1, 2014.

- ^ Крымские власти объявили о подчинении Януковичу. lenta.ru (in Russian). February 28, 2014.

- ^ "ПОСТ "ЧОНГАР" КОНТРОЛИРУЕТ КРЫМСКИЙ "БЕРКУТ" ПОДЧИНЕННЫЙ ЯНУКОВИЧУ видео) - 27 Февраля 2014 - "Новый Визит" Генический информационный портал".

- ^ "-".

- ^ Армянск Информационный. "Армянск Информационный - Под Армянск стянулись силовики из "Беркута"".

- ^ "Lenta.ru: Бывший СССР: Украина: СМИ сообщили о блокпостах "Беркута" на въездах в Крым".

- ^ "Hundreds of thousands gather in Sevastopol to watch Victory Day parade". TASS. May 9, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ "Премьер-министр Крыма попросил Путина о помощи". ITAR-TASS.

- ^ Владимир Путин внёс обращение в Совет Федерации. kremlin.ru (in Russian).

- ^ Постановление Совета Федерации Федерального Собрания Российской Федерации от 1 марта 2014 года № 48-СФ "Об использовании Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации на территории Украины" (PDF). council.gov.ru (in Russian).

- ^ "Russian Parliament approves use of army in Ukraine".

- ^ Walker, Shaun (March 4, 2014). "Russian takeover of Crimea will not descend into war, says Vladimir Putin". The Guardian. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Yoon, Sangwon; Krasnolutska, Daryna; Choursina, Kateryna (March 4, 2014). "Russia Stays in Ukraine as Putin Channels Yanukovych Request". Bloomberg News. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Russia says cannot order Crimean 'self-defense' units back to base".

- ^ "Speech by the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and his answers to questions from the mass media summarising the meeting with EU, Russian, US and Ukrainian representatives, Geneva, 17 April 2014".

- ^ "Direct Line with Vladimir Putin". kremlin.ru. April 17, 2014.

- ^ Шойгу: действия Минобороны РФ в Крыму были вызваны угрозой жизни мирного населения (in Russian). ITAR-TASS. April 4, 2014.

- ^ "Russia redeploys ships of Baltic and Northern fleets to Sevastopol, violates agreement with Ukraine". Ukrinform. March 3, 2014.

- ^ "telegraph.co.uk: "Vladimir Putin's illegal occupation of Crimea is an attempt to put Europe's borders up for grabs" (Crawford) 10 Mar 2014". blogs.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Joint Statement by the United States and Ukraine". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. March 25, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ "Медведев: Россия не гарантирует целостность Украины" [Medvedev: Russia does not guarantee the integrity of Ukraine]. BBC (in Russian). May 20, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ "Statement by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs regarding accusations of Russia's violation of its obligations under the Budapest Memorandum of 5 December 1994". Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. May 1, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ "Constitution of the Russian Federation".

- ^ "Opinion on "Whether Draft Federal constitutional Law No. 462741-6 on amending the Federal constitutional Law of the Russian Federation on the procedure of admission to the Russian Federation and creation of a new subject within the Russian Federation is compatible with international law" endorsed by the Venice Commission at its 98th Plenary Session (Venice, 21-22 March 2014)". Venice Commission. March 21–22, 2014.

- ^ "Draft Federal Constitutional Law of the Russian Federation "amending the Federal Constitutional Law on the Procedure of Admission to the Russian Federation and creation of a new subject of the Russian Federation in its composition" of the Russian Federation (translation)". March 10, 2014.

- ^ "CDL-AD(2014)004-e Opinion on "Whether Draft Federal constitutional Law No. 462741-6 on amending the Federal constitutional Law of the Russian Federation on the procedure of admission to the Russian Federation and creation of a new subject within the Russian Federation is compatible with international law" endorsed by the Venice Commission at its 98th Plenary Session (Venice, 21-22 March 2014)". Venice Commission. March 2014.

- ^ Крым определился, каким способом войдет в Россию (in Russian). Vedomosti. March 11, 2014.

- ^ Законопроект № 462741-6 О внесении изменений в Федеральный конституционный закон "О порядке принятия в Российскую Федерацию и образования в ее составе нового субъекта Российской Федерации" (в части расширения предмета правового регулирования названного Федерального конституционного закона). duma.gov.ru (in Russian).

- ^ "Постановление ВР АРК "Об организации и проведении республиканского (местного) референдума по вопросам усовершенствования статуса и полномочий Автономной Республики Крым"". Rada.crimea.ua. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- ^ Аксенов: перенос референдума в Крыму связан с тем, что конфликт вышел за пределы разумного. Interfax (in Russian).

- ^ "Суд признал незаконными назначение Аксенова премьером и проведение референдума в Крыму". Unian.net. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- ^ Россия не рассматривает вариант присоединения Крыма к России (in Russian). Interfax. March 4, 2014.

- ^ Путин: Россия не планировала присоединять Крым (in Russian). ITAR-TASS. April 10, 2014.

- ^ Референдум в Крыму: ответ "нет" не предусмотрен. Voice of America (in Russian).

- ^ "КС признал неконституционным постановление о проведении референдума в Крыму - Видео".

- ^ Про дострокове припинення повноважень Верховної Ради Автономної Республіки Крим (in Ukrainian).

- ^ "Crimea referendum Wide condemnation after region votes to split from Ukraine Fox News". Fox News. March 16, 2014.

- ^ Halimah, Halimah (March 17, 2014). "Crimea's vote: Was it legal?". CNN. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ Paul Roderick Gregory (May 5, 2014). "Putin's 'Human Rights Council' Accidentally Posts Real Crimean Election Results". Forbes.

- ^ a b "Russian government agency reveals fraudulent nature of the Crimean referendum results". Washington Post.

- ^ Проблемы жителей Крыма Template:Ru icon

- ^ "The Kremlin's marriage of convenience with the European far right". oDR. April 28, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ^ "Extreemrechtse partijen uitgenodigd op referendum Krim" (in Dutch). De Redactie. March 13, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ^ "Referendum day in Crimea's Simferopol". Deutsche Welle. March 16, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ^ Постановление Верховной Рады Автономной Республики Крым от 17 марта 2014 года № 1745-6/14 "О независимости Крыма". www.rada.crimea.ua (in Russian).

- ^ Парламент Крыма национализировал порты полуострова и их имущество. nbnews.com.ua (in Russian). March 17, 2014.

- ^ Крым национализировал "Черноморнефтегаз". glavred.info (in Russian). March 17, 2014.

- ^ "Crimea applies to be part of Russian Federation after vote to leave Ukraine". The Guardian. March 17, 2014.

- ^ Крым начал процедуру присоединения к РФ, объявив о независимости (in Russian). RIA Novosti. March 17, 2014.

- ^ " "Russian ruble announced Crimea's official currency". ITAR-TASS. March 17, 2014.

- ^ Названа дата перехода Крыма на московское время. Lenta.ru (in Russian). March 17, 2014.

- ^ "Executive Order on recognising Republic of Crimea". Kremlin. March 17, 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ Template:Wayback at http://www.pravo.gov.ru Template:Ru icon

- ^ "Договор между Российской Федерацией и Республикой Крым о принятии в Российскую Федерацию Республики Крым и образовании в составе Российской Федерации новых субъектов". Kremlin.ru. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- ^ Ukraine crisis: Putin signs Russia-Crimea treaty, BBC, 18 March 2014

- ^ "Crimea, Sevastopol officially join Russia as Putin signs final decree". RT. March 22, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ "Putin submits Treaty on Crimea's accession, new constitutional amendment to State Duma". En.itar-tass.com. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ "Treaty on Crimea's accession to Russia corresponds to Russian Constitution". En.itar-tass.com. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ "Russian Constitutional Court Backs Crimea Reunification, RIA NOVOSTI". En.ria.ru. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ "State Duma ratifies treaty on admission of Crimea into Russia". ITAR TASS. March 20, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ "Госдума приняла закон о присоединении Крыма". Rossiyskaya Gazeta. March 20, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ "Справка о голосовании по вопросу:О проекте федерального конституционного закона № 475944-6 "О принятии в Российскую Федерацию Республики Крым и образовании в составе Российской Федерации новых субъектов - Республики Крым и города федерального значения Севастополя" (первое чтение)". Vote.duma.gov.ru. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ "Справка о голосовании по вопросу: О проекте федерального конституционного закона № 475944-6 "О принятии в Российскую Федерацию Республики Крым и образовании в составе Российской Федерации новых субъектов - Республики Крым и города федерального значения Севастополя" (в целом)". Vote.duma.gov.ru. March 20, 2014. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- ^ "Russian Federation Council ratifies treaty on Crimea's entry to Russia". ITAR TASS. March 21, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Подписаны законы о принятии Крыма и Севастополя в состав России kremlin.ru Template:Ru icon

- ^ "Федеральный конституционный закон от 21 марта 2014 г. N 6-ФКЗ "О принятии в Российскую Федерацию Республики Крым и образовании в составе Российской Федерации новых субъектов - Республики Крым и города федерального значения Севастополя"" (in Russian).

Article 1.<...>3. Republic of Crimea shall be considered admitted to the Russian Federation since date of signing of the Agreement between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Crimea on the Accession of the Republic of Crimea to the Russian Federation and the Formation of New Federal Constituent Entities within the Russian Federation

- ^ "Ukraine orders Crimea troop withdrawal as Russia seizes naval base". CNN. March 24, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Ukrainian News - Defense Ministry: 50% Of Ukrainian Troops In Crimea Defect To Russia". Un.ua. March 24, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ Jonathan Marcus (March 24, 2014). "BBC News - Ukrainian forces withdraw from Crimea". Bbc.com. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ "United Nations News Centre - Backing Ukraine's territorial integrity, UN Assembly declares Crimea referendum invalid". Un.org. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ Charbonneau, Louis. "U.N. General Assembly declares Crimea secession vote invalid". Reuters. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ "В 22.00 в Крыму и в Севастополе стрелки часов переведут на два часа вперёд – на московское время". March 29, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ "Crimea to set clocks to Russia time".

- ^ Прекращено действие соглашений, касающихся пребывания Черноморского флота на Украине Kremlin.ru Template:Ru icon

- ^ See Presidential explanatory note to the denunciation bill Template:Ru icon

- ^ Nikiforov, Vadim (March 12, 2014). Крым и Севастополь ожидают представления свыше (in Russian). Kommersant. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ Nezamyatnyj, Ivan (April 11, 2014). Крым прописался в конституции России. mk.ru (in Russian).

- ^ "Российские туристы поедут в Крым, если ...смогут туда добраться". Komsomolskaya Pravda. July 17, 2013.

- ^ "Крым готовится к референдуму и ожидает Русских сезонов". РИА Оренбуржье. March 17, 2014.

- ^ "Снова в "Артек"". Vzglyad. March 17, 2014.

- ^ "Die Welt: Crimea's Accession Will Cost Russia Billions". Novinite. March 17, 2014.

- ^ "Расходный полуостров". Kommersant. March 7, 2014.

- ^ "In taking Crimea, Putin gains a sea of fuel reserves". Times of India. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ^ Crimea: an EU-US-Exxon Screwup. Counterpunch.org. 23–25 May 2014.

- ^ "Оздоровлением курортов Крыма займется Руслан Байсаров". Top.rbc.ru. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ "Central Telegraph to set Russian tariffs on telegrams in Crimea Apr 3". Prime. March 26, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ "Крымчанам придется поменять номера телефонов и SIM-карты". comnews.ru. March 19, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ ""Почта России" переводит почтовое сообщение с Крымом на российские тарифы". comnews.ru. March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Russian state border in north Crimea to be fully equipped in early May". ITAR TASS. April 29, 2014. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ "Sneaking into Crimea - Or Maybe Not". Forbes. May 30, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ О пунктах пропуска через государственную границу России в Республике Крым и городе Севастополе

- ^ "Government Order on checkpoints at the Russian border in the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol". Government of Russia official website. June 7, 2014. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ^ Mills, Laura; Dahlburg, John-Thor (December 2, 2014). "Change of leadership in Crimea means property grab". Associated Press.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Neil (January 10, 2015). "Seizing Assets in Crimea, From Shipyard to Film Studio". The New York Times.

- ^ Antonova, Maria (February 27, 2015). "Under Russia, isolated Crimea is twilight zone for business". Agence France-Presse. Yahoo News. Archived from the original on March 1, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Федеральный закон от 28.12.2013 N 433-ФЗ "О внесении изменения в Уголовный кодекс Российской Федерации" Template:Ru icon

- ^ Автор статьи: Мария Макутина. "За призывы вернуть Крым Украине можно будет лишиться свободы сроком до пяти лет - РБК daily". Rbcdaily.ru. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ "70-". .Ru.

- ^ a b Hille, Katherine (May 18, 2014). "Crimean Tatars defy ban on rallies to commemorate deportation". Financial Tims. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Winning, Alexander (May 18, 2014). "Crimean Tatars commemorate Soviet deportation despite ban". Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- ^ "Crimea helicopters try to disrupt Tatar rallies". BBC. BBC. May 18, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- ^ МИД вызвал Временного поверенного в делах РФ в Украине для вручения ноты-протеста. unn.com.ua (in Russian). March 18, 2014.

- ^ Декларація "Про боротьбу за звільнення України". rada.gov.ua (in Ukrainian).

- ^ Верховна Рада України ухвалила Закон "Про забезпечення прав і свобод громадян та правовий режим на тимчасово окупованій території України" (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada. April 15, 2014.

- ^ Верховная Рада Украины приняла Закон "Об обеспечении прав и свобод граждан и правовом режиме на временно оккупированной территории Украины" (in Russian). Verkhovna Rada. April 15, 2014.

- ^ Рада приняла закон о защите прав граждан "оккупированного Крыма". vz.ru (in Russian). April 15, 2014.

- ^ USA TODAY Research and Ashley M. Williams (March 15, 2014). "Russia vetoes U.N. resolution on Crimea's future". www.usatoday.com. usatoday. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ "GENERAL ASSEMBLY ADOPTS RESOLUTION CALLING UPON STATES NOT TO RECOGNIZE CHANGES IN STATUS OF CRIMEA REGION". www.un.org. UN. March 27, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine: UN condemns Crimea vote as IMF and US back loans". www.bbc.com. BBC. March 27, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ "Afghan president Hamid Karzai backs Russia's annexation of Crimea". The Guardian. March 24, 2014. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ "Visiting Russia, Fidel Castro's Son Scoffs at U.S. Sanctions Over Crimea - News". The Moscow Times.

- ^ "Nicaragua recognizes Crimea as part of Russia". Kyiv Post. March 27, 2014.

- ^ КНДР одобрила присоединение Крыма к России. Lenta.ru. 2014-12-30.

- ^ Russian Federation Council ratifies treaty on Crimea’s entry to Russia. itar-tass.com. 21 March 2014

- ^ a b "Gunmen Seize Government Buildings in Crimea". The New York Times. February 27, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

Masked men with guns seized government buildings in the capital of Ukraine's Crimea region on Thursday, barricading themselves inside and raising the Russian flag after mysterious overnight raids that appeared to be the work of militant Russian nationalists who want this volatile Black Sea region ruled from Moscow.

- ^ President of the Republic of Belarus Alexander Lukashenko answers questions of mass media representatives on 23 March 2014. president.gov.by. 23 March 2014.

- ^ "Transnistria wants to merge with Russia". Vestnik Kavkaza. March 18, 2014. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ^ "Moldova's Trans-Dniester region pleads to join Russia". Bbc.com. March 18, 2014. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ^ "Dniester public organizations ask Russia to consider possibility of Transnistria accession". En.itar-tass.com. March 18, 2014. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ^ Gianluca Mezzofiore (April 16, 2014). "Transnistria Urges Kremlin and UN to Recognise Independence". International Business Times. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Peskov: Putin aware of Transnistria's request on independence recognition". KyivPost. April 17, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Глава Минфина ФРГ: Я не сравнивал Россию с нацистской Германией. top.rbc.ru (in Russian). April 4, 2014.

- ^ "Merkel: Crimea grab 'against international law'".

- ^ "EUobserver / Merkel: Comparing Crimea to Kosovo is 'shameful'".

- ^ Nicholas Watt. "Ukraine: UK to push for tougher sanctions against Russia over Crimea". the Guardian.

- ^ Laura Smith-Spark, Diana Magnay and Nick Paton Walsh, CNN (March 16, 2014). "Ukraine crisis: Early results show Crimea votes to join Russia". CNN.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "European Commission - PRESS RELEASES - Press release - Joint statement on Crimea by the President of the European Council, Herman Van Rompuy, and the President of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso".

- ^ "Cold War Ghosts Haunt East Europe in Moves for Crimea". Bloomberg. 3 March 2014

- ^ Kramer, David J. (December 22, 2014). ""We Have Allowed Aggression to Stand"". The American Interest.

- ^ "Mikhail Gorbachev hails Crimea annexation to Russia". United Press International. 18 March 2014.

- ^ "President of Russia". Eng.kremlin.ru. March 21, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ^ "Japan imposes sanctions against Russia over Crimea independence". Fox News. March 18, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Russia sanctions 9 US officials in response to US sanctions on Russian officials". CNBC. March 20, 2014.

- ^ a b "All Russian MPs volunteer to be subject to US, EU sanctions". 2014-03-18. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ Sanctions tit-for-tat: Moscow strikes back against US officials RT Retrieved on 20 March 2014

- ^ a b c d Lowery & O'Keefe, Wesley & Ed (March 20, 2014). "Reacting to sanctions, Russians ban Reid, Boehner and four other lawmakers". Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d Isherwood, Darryl (March 20, 2014). "Bob Menendez is banned from Russia". NJ.

- ^ a b c Weigel, David (March 20, 2014). "Senators Celebrate Being Sanctioned by Russia". Slate.

- ^ Buckley, Neil (March 21, 2014). "Putin feels the heat as sanctions target president's inner circle". ft.com. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (March 21, 2014). "European Union prepares for trade war with Russia over Crimea". theguardian.com. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- ^ a b Tanas, Olga (March 21, 2014). "Russia's Credit Outlook Cut as U.S., EU Widen Sanction Lists". bloomberg.com. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Farchy, Jack; Hille, Kathrin; Weaver, Courtney (March 21, 2014). "Russian executives quake as US sanctions rattle markets". ft.com. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Matzen, Eric; Martin, Michelle (March 21, 2014). "Russian sanctions ripple through corporate boardrooms". Reuters. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Hille, Kathrin (March 21, 2014). "Putin boosted by defiant tone at top and among people". ft.com. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Alpert, Lukas I.; Sonne, Paul (March 21, 2014). "Russia Sends Mixed Signals in Response to U.S. Sanctions". wsj.com. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ "Statement Regarding the Mapping of Crimea". National Geographic Society. March 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g КРЫМ НА КАРТАХ МИРА: СИТУАЦИЯ ПОМЕНЯЛАСЬ. hi-tech.mail.ru (in Russian). April 11, 2014.

- ^ "Google сделала Крым российским на картах для рунета". lenta.ru (in Russian). April 11, 2014.

- ^ Kyle O'Donnell and Julie Johnsson (March 22, 2014). "Russian Cartographers Add Crimea to Maps Amid Sanctions". bloomberg.com.

- ^ "Яндекс" показывает разные карты в России и на Украине. slon.ru (in Russian). March 22, 2014.

- ^ "Parliament challenges mapmakers to mark Crimea Russian territory". en.itar-tass.com. March 26, 2014.

- ^ "Statement by the DWG on edit conflicts in Crimea". OpenStreetMap Foundation. June 5, 2014.

In the short-term Crimea shall remain in both the Ukraine and Russia administrative relations, and be indicated as disputed. We recognize that being in two administrative relations is not a good long-term solution, although the region is likely to be indicated as disputed for some time.

- ^ "Mail.ru и Yandex изменят карты в связи с присоединением Крыма к России" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. March 19, 2014.