Al Capone

Al Capone | |

|---|---|

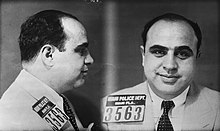

Al Capone in 1930 | |

| Born | Alphonse Gabriel Capone January 17, 1899 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | January 25, 1947 (aged 48) Palm Island, Florida, U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Carmel Cemetery Hillside, Illinois, U.S. |

| Other names | Scarface, Big Al, Big Boy, Public Enemy No. 1, Snorky |

| Occupation(s) | Gangster, bootlegger, racketeer, boss of Chicago Outfit |

| Known for | Boss of the Chicago Outfit, and the Saint Valentine's Day Massacre |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives | 8 siblings, including James Vincenzo Capone, Ralph Capone and Frank Capone |

| Allegiance | Chicago Outfit |

| Criminal charge | Tax evasion |

| Penalty | 11 years' imprisonment (1931) |

| Signature | |

Alphonse Gabriel Capone (/kəˈpoʊn/,[1] Italian: [kaˈpoːne]; January 17, 1899 – January 25, 1947), sometimes known by the nickname "Scarface", was an American gangster and businessman who attained notoriety during the Prohibition era as the co-founder and boss of the Chicago Outfit. His seven-year reign as a crime boss ended when he went to prison at the age of 33.

Capone was born in New York City in 1899 to Italian immigrant parents. He joined the Five Points Gang as a teenager, and became a bouncer in organized crime premises such as brothels. In his early twenties he moved to Chicago and became a bodyguard and trusted factotum for Johnny Torrio, head of a criminal syndicate that illegally supplied alcohol—the forerunner of the Outfit—and was politically protected through the Unione Siciliana. A conflict with the North Side Gang was instrumental in Capone's rise and fall. Torrio went into retirement after North Side gunmen almost killed him, handing control to Capone. Capone expanded the bootlegging business through increasingly violent means, but his mutually profitable relationships with mayor William Hale Thompson and the city's police meant he seemed safe from law enforcement.

Capone apparently reveled in attention, such as the cheers from spectators when he appeared at ball games. He made donations to various charities and was viewed by many as "modern-day Robin Hood". However, the Saint Valentine's Day Massacre, in which seven gang rivals were murdered in broad daylight, damaged the public images of Chicago and Capone, leading influential citizens to demand government action and newspapers to dub Capone "Public Enemy No. 1".

The federal authorities became intent on jailing Capone, and prosecuted him in 1931 for tax evasion. During a highly publicized case, the judge admitted as evidence Capone's admissions of his income and unpaid taxes, made during prior (and ultimately abortive) negotiations to pay the government taxes he owed. He was convicted and sentenced to 11 years in federal prison. After conviction, he replaced his defense team with experts in tax law, and his grounds for appeal were strengthened by a Supreme Court ruling, but his appeal ultimately failed. Capone showed signs of neurosyphilis early in his sentence, and became increasingly debilitated before being released after almost eight years of incarceration. On January 25, 1947, he died of cardiac arrest after suffering a stroke.

Early life and education

Capone was born in Brooklyn, New York on January 17, 1899.[2] His parents were Italian immigrants Gabriele Capone (1865–1920) and Teresa Capone (née Raiola; 1867–1952).[3] His father was a barber and his mother was a seamstress, both born in Angri, a small commune outside of Naples in the Province of Salerno.[4][5]

Gabriele and Teresa had eight other children: Vincenzo Capone, who later changed his name to Richard Hart and became a Prohibition agent in Homer, Nebraska; Raffaele James Capone, also known as Ralph "Bottles" Capone, who took charge of his brother's beverage industry; Salvatore "Frank" Capone, Ermina Capone, who died at the age of one, Ermino "John" Capone, Albert Capone, Matthew Capone, and Mafalda Capone. Ralph and Frank worked with him in his criminal empire. Frank did so until his death on April 1, 1924.[6] Ralph ran the bottling companies (both legal and illegal) early on, and was also the front man for the Chicago Outfit for some time until he was imprisoned for tax evasion in 1932.[7]

The Capone family first immigrated in 1893 from Southern Italy to Fiume (modern-day Rijeka, Croatia), a port city in what was then Austria-Hungary.[2][8] That year, the family traveled from Fiume by ship to the U.S., where they settled at 95 Navy Street, in the Navy Yard section of downtown Brooklyn.[2] Gabriele Capone worked at a nearby barber shop at 29 Park Avenue. When Al was 11, the Capone family moved to 38 Garfield Place in Park Slope, Brooklyn.[2]

Capone showed promise as a student, but had trouble with the rules at his strict parochial Catholic school. His schooling ended at the age of 14, after he was expelled for hitting a female teacher in the face.[9] He worked at odd jobs around Brooklyn, including a candy store and a bowling alley.[10] From 1916 to 1918, he played semi-professional baseball.[11] Following this, Capone was influenced by gangster Johnny Torrio, whom he came to regard as a mentor.[12]

Career

Capone initially became involved with small-time gangs that included the Junior Forty Thieves and the Bowery Boys. He then joined the Brooklyn Rippers, and then the powerful Five Points Gang based in Lower Manhattan. During this time, he was employed and mentored by fellow racketeer Frankie Yale, a bartender in a Coney Island dance hall and saloon called the Harvard Inn. Capone inadvertently insulted a woman while working the door at a Brooklyn night club and was slashed by her brother Frank Gallucio. The wounds led to the nickname "Scarface" which Capone loathed.[13][14][15] When he was photographed, he hid the scarred left side of his face, saying that the injuries were war wounds.[14][16] He was called "Snorky" by his closest friends, a term for a sharp dresser.[17]

Marriage and family

Capone married Mae Josephine Coughlin at age 19, on December 30, 1918. She was Irish Catholic and earlier that month had given birth to their son Albert Francis "Sonny" Capone (1918–2004). Albert lost most of his hearing in his left ear as a child. Capone was under the age of 21, and his parents had to consent in writing to the marriage.[18] By all accounts, the two had a happy marriage despite his criminal lifestyle.[19]

Chicago

In 1919, Capone left New York City for Chicago at the invitation of Johnny Torrio, who was imported by crime boss James "Big Jim" Colosimo as an enforcer. Capone began in Chicago as a bouncer in a brothel, where he contracted syphilis. Timely use of Salvarsan probably could have cured the infection, but he apparently never sought treatment.[20] In 1923, he purchased a small house at 7244 South Prairie Avenue in the Park Manor neighborhood on the city's south side for US$5,500.[21] In the early years of the decade, his name began appearing in newspaper sports pages where he was described as a boxing promoter.[22] Torrio took over Colosimo's crime empire after Colosimo's murder on May 11, 1920, in which Capone was suspected of being involved.[9][23][24]

Torrio headed an essentially Italian organized crime group that was the biggest in the city, with Capone as his right-hand man. He was wary of being drawn into gang wars and tried to negotiate agreements over territory between rival crime groups. The smaller North Side Gang led by Dean O'Banion (also known as Dion O'Banion) was of mixed ethnicity, and it came under pressure from the Genna brothers who were allied with Torrio. O'Banion found that Torrio was unhelpful with the encroachment of the Gennas into the North Side, despite his pretensions to be a settler of disputes.[25] In a fateful step, Torrio either arranged for or acquiesced to the murder of O'Banion at his flower shop on November 10, 1924. This placed Hymie Weiss at the head of the gang, backed by Vincent Drucci and Bugs Moran. Weiss had been a close friend of O'Banion, and the North Siders made it a priority to get revenge on his killers.[26][27][28]

Al Capone was a frequent visitor to RyeMabee in Monteagle, Tennessee "when he was traveling between Chicago and his Florida estate in Miami."[29]

Boss

In January 1925, Capone was ambushed, leaving him shaken but unhurt. Twelve days later, Torrio was returning from a shopping trip when he was shot several times. After recovering, he effectively resigned and handed control to Capone, age 26, who became the new boss of an organization that took in illegal breweries and a transportation network that reached to Canada, with political and law-enforcement protection. In turn, he was able to use more violence to increase revenue. An establishment that refused to purchase liquor from him often got blown up, and as many as 100 people were killed in such bombings during the 1920s. Rivals saw Capone as responsible for the proliferation of brothels in the city.[28][30][31][32]

Capone indulged in custom suits, cigars, gourmet food and drink (his preferred liquor was Templeton Rye from Iowa),[33] and female companionship. He was particularly known for his flamboyant and costly jewelry. His favorite responses to questions about his activities were: "I am just a businessman, giving the people what they want"; and, "All I do is satisfy a public demand." Capone had become a national celebrity and talking point.[13]

He based himself in Cicero, Illinois after using bribery and widespread intimidation to take over town council elections (such as the 1924 Cicero municipal elections), and this made it difficult for the North Siders to target him.[13] His driver was found tortured and murdered, and there was an attempt on Weiss's life in the Chicago Loop. On September 20, 1926, the North Side Gang used a ploy outside the Capone headquarters at the Hawthorne Inn, aimed at drawing him to the windows. Gunmen in several cars then opened fire with Thompson submachine guns and shotguns at the windows of the first-floor restaurant. Capone was unhurt and called for a truce, but the negotiations fell through. Three weeks later, Weiss was killed outside the former O'Banion flower shop North Side headquarters. The owner of Hawthorne's restaurant was a friend of Capone's, and he was kidnapped and killed by Moran and Drucci in January 1927.[34][35]

Capone became increasingly security-minded and desirous of getting away from Chicago.[35][36] As a precaution, he and his entourage would often show up suddenly at one of Chicago's train depots and buy up an entire Pullman sleeper car on a night train to Cleveland, Omaha, Kansas City, Little Rock, or Hot Springs, where they would spend a week in luxury hotel suites under assumed names. In 1928, Capone paid $40,000 to beer magnate August Busch for a 14-room retreat at 93 Palm Avenue on Palm Island, Florida, in Biscayne Bay between Miami and Miami Beach.[37][13] He never registered any property under his name. He did not even have a bank account, but he always used Western Union for cash delivery, although not more than $1,000.[38] In an effort to clean up his image, Capone donated to charities and sponsored a soup kitchen in Chicago during the Depression.[39][40]

Political alliances

The protagonists of Chicago's politics had long been associated with questionable methods, and even newspaper circulation "wars", but the need for bootleggers to have protection in city hall introduced a far more serious level of violence and graft. Capone is generally seen as having an appreciable effect in bringing about the victories of Republican William Hale Thompson, especially in the 1927 mayoral race when Thompson campaigned for a wide open town, at one time hinting that he'd reopen illegal saloons.[41] Such a proclamation helped his campaign gain the support of Capone, and he allegedly accepted a contribution of $250,000 from the gangster. In the 1927 mayoral race, Thompson beat William Emmett Dever by a relatively slim margin.[42][43] Thompson's powerful Cook County political machine had drawn on the often-parochial Italian community, but this was in tension with his highly successful courting of African Americans.[44][45][46]

Capone continued to back Thompson. Voting booths were targeted by Capone's bomber James Belcastro in the wards where Thompson's opponents were thought to have support, on the polling day of April 10, 1928, in the so-called Pineapple Primary, causing the deaths of at least 15 people. Belcastro was accused of the murder of lawyer Octavius Granady, an African American who challenged Thompson's candidate for the African American vote, and was chased through the streets on polling day by cars of gunmen before being shot dead. Four policemen were among those charged along with Belcastro, but all charges were dropped after key witnesses recanted their statements. An indication of the attitude of local law enforcement to Capone's organization came in 1931 when Belcastro was wounded in a shooting; police suggested to skeptical journalists that Belcastro was an independent operator.[47][48][49][50][51]

The 1929 Saint Valentine's Day Massacre led to public disquiet about Thompson's alliance with Capone and was a factor in Anton J. Cermak winning the mayoral election on April 6, 1931.[52]

Saint Valentine's Day Massacre

Capone was widely assumed to have been responsible for ordering the 1929 Saint Valentine's Day Massacre in an attempt to eliminate Bugs Moran, head of the North Side Gang. Moran was the last survivor of the North Side gunmen; his succession had come about because his similarly aggressive predecessors Vincent Drucci and Hymie Weiss had been killed in the violence that followed the murder of original leader Dean O'Banion.[13][53][54]

To monitor their targets' habits and movements, Capone's men rented an apartment across from the trucking warehouse and garage at 2122 North Clark Street, which served as Moran's headquarters. On the morning of Thursday, February 14, 1929,[55][56] Capone's lookouts signaled gunmen disguised as police officers to initiate a "police raid". The faux police lined the seven victims along a wall and signaled for accomplices armed with machine guns and shotguns. Photos of the slain victims shocked the public and damaged Capone's reputation. Within days, Capone received a summons to testify before a Chicago grand jury on charges of federal Prohibition violations, but he claimed to be too unwell to attend.[57]

Capone was primarily known for ordering other men to do his dirty work for him. One story, however, has Capone, having discovered that three of his men—Scalise, Anselmi, and Giunta—were conspiring against him with a rival gangster, Joe Aiello, reportedly arranging for the conspirators to dine with him and his bodyguards.[58] After a night of drinking, Capone beat the men with a baseball bat and then ordered his bodyguards to shoot them, a scene that was included in the 1987 film The Untouchables.[59] Deirdre Bair, along with writers and historians such as William Elliot Hazelgrove, have questioned the veracity of the claim.[59][60] Bair questioned why "three trained killers could sit quietly and let this happen", while Hazelgrove stated that Capone would have been "hard pressed to beat three men to death with a baseball bat" and that he would have instead let an enforcer perform the murders.[59][60] However, despite claims that the story was first reported by author Walter Noble Burns in his 1931 book The One-way Ride: The red trail of Chicago gangland from prohibition to Jake Lingle,[59] Capone biographers Max Allan Collins and A. Brad Schwartz have found versions of the story in press coverage shortly after the crime. Collins and Schwartz suggest that similarities among reported versions of the story indicate a basis in truth and that the Outfit deliberately spread the tale to enhance Capone's fearsome reputation.[61]: xvi, 209–213, 565 George Meyer, an associate of Capone's, also claimed to have witnessed both the planning of the murders and the event itself.[2]

Trials

On March 27, 1929, Capone was arrested by FBI agents as he left a Chicago courtroom after testifying to a grand jury that was investigating violations of federal prohibition laws. He was charged with contempt of court for feigning illness to avoid an earlier appearance.[62] On May 16, 1929, Capone was arrested in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania for carrying a concealed weapon. On May 17, 1929, Capone was indicted by a grand jury and a trial was held before Philadelphia Municipal Court Judge John E Walsh. Following the entering of a guilty plea by his attorney, Capone was sentenced to a prison term of one year.[63] On August 8, 1929, Capone was transferred to Philadelphia's Eastern State Penitentiary. A week after his release in March 1930, Capone was listed as the number one "Public Enemy" on the unofficial Chicago Crime Commission's widely publicized list.[64]

In April 1930, Capone was arrested on vagrancy charges when visiting Miami Beach; the governor had ordered sheriffs to run him out of the state. Capone claimed that Miami police had refused him food and water and threatened to arrest his family. He was charged with perjury for making these statements, but was acquitted after a three-day trial in July.[65] In September, a Chicago judge issued a warrant for Capone's arrest on charges of vagrancy, and then used the publicity to run against Thompson in the Republican primary.[66][67] In February 1931, Capone was tried on the contempt of court charge. In court, Judge James Herbert Wilkerson intervened to reinforce questioning of Capone's doctor by the prosecutor. Wilkerson sentenced Capone to six months, but he remained free while on appeal of the contempt conviction.[68][69]

Tax evasion

Assistant Attorney General Mabel Walker Willebrandt recognized that mob figures publicly led lavish lifestyles yet never filed tax returns, and thus could be convicted of tax evasion without requiring hard evidence to get testimony about their other crimes. She tested this approach by prosecuting a South Carolina bootlegger, Manley Sullivan.[70] In 1927, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Sullivan that the approach was legally sound: illegally earned income was subject to income tax; Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. rejected the argument that the Fifth Amendment protected criminals from reporting illegal income.[71]

The IRS special investigation unit chose Frank J. Wilson to investigate Capone, with the focus on his spending. The key to Capone's conviction on tax charges was proving his income, and the most valuable evidence in that regard originated in his offer to pay tax. Ralph, his brother and a gangster in his own right, was tried for tax evasion in 1930. Ralph spent the next three years in prison after being convicted in a two-week trial over which Wilkerson presided.[72] Capone ordered his lawyer to regularize his tax position. Crucially, during the ultimately abortive negotiations that followed, his lawyer stated the income that Capone was willing to pay tax on for various years, admitting income of $100,000 for 1928 and 1929, for instance. Hence, without any investigation, the government had been given a letter from a lawyer acting for Capone conceding his large taxable income for certain years. On March 13, 1931, Capone was charged with income tax evasion for 1924, in a secret grand jury.[73] On June 5, 1931, Capone was indicted by a federal grand jury on 22 counts of income tax evasion from 1925 through 1929; he was released on $50,000 bail.[73] A week later, Eliot Ness and his team of Untouchables inflicted major financial damage on Capone's operations, and led to his indictment on 5,000 violations of the Volstead Act (Prohibition laws).[73][61]: 385–421, 493–496 [74][73]

On June 16, 1931, at the Chicago Federal Building in the courtroom of Judge James Herbert Wilkerson, Capone plead guilty to income tax evasion and the 5,000 Volstead Act violations as part of a 2+1⁄2-year prison sentence plea bargain.[73] However, on July 30, 1931, Judge Wilkerson refused to honor the plea bargain, and Capone's counsel rescinded the guilty pleas.[73] On the second day of the trial, Judge Wilkerson overruled objections that a lawyer could not confess for his client, saying that anyone making a statement to the government did so at his own risk. Wilkerson deemed that the 1930 letter to federal authorities could be admitted into evidence from a lawyer acting for Capone.[75][76][77] Wilkerson later tried Capone only on the income tax evasion charges as he determined they took precedence over the Volstead Act charges.[73]

Much was later made of other evidence, such as witnesses and ledgers, but these strongly implied Capone's control rather than stating it. Capone's lawyers, who had relied on the plea bargain Judge Wilkerson refused to honor and therefore had mere hours to prepare for the trial, ran a weak defense focused on claiming that essentially all his income was lost to gambling.[78] This would have been irrelevant regardless, since gambling losses can only be subtracted from gambling winnings, but it was further undercut by Capone's expenses, which were well beyond what his claimed income could support; Judge Wilkerson allowed Capone's spending to be presented at very great length.[78] The government charged Capone with evasion of $215,000 in taxes on a total income of $1,038,654, during the five-year period.[73] Capone was convicted on three counts of income tax evasion on October 17, 1931,[79][80][81] and was sentenced a week later to 11 years in federal prison, fined $50,000 plus $7,692 for court costs, and was held liable for $215,000 plus interest due on his back taxes.[82][83][84][85] The contempt of court sentence was served concurrently.[86][87][88][89] New lawyers hired to represent Capone were Washington-based tax experts. They filed a writ of habeas corpus based on a Supreme Court ruling that tax evasion was not fraud, which apparently meant that Capone had been convicted on charges relating to years that were actually outside the time limit for prosecution. However, a judge interpreted the law so that the time that Capone had spent in Miami was subtracted from the age of the offences, thereby denying the appeal of both Capone's conviction and sentence.[90][91]

Imprisonment

Capone was sent to Atlanta U.S. Penitentiary in May 1932, aged 33. Upon his arrival at Atlanta, the 250-pound (110 kg) Capone was officially diagnosed with syphilis and gonorrhoea. He was also suffering from withdrawal symptoms from cocaine addiction, the use of which had perforated his nasal septum. Capone was competent at his prison job of stitching soles on shoes for eight hours a day, but his letters were barely coherent.[92] He was seen as a weak personality, and so out of his depth dealing with bullying fellow inmates that his cellmate, seasoned convict Red Rudensky, feared that Capone would have a breakdown. Rudensky was formerly a small-time criminal associated with the Capone gang, and found himself becoming a protector for Capone.[92] The conspicuous protection of Rudensky and other prisoners drew accusations from less friendly inmates, and fueled suspicion that Capone was receiving special treatment. No solid evidence ever emerged, but it formed part of the rationale for moving Capone to the recently opened Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary off the coast of San Francisco, in August 1934.[92][93] On June 23, 1936, Capone was stabbed and superficially wounded by fellow-Alcatraz inmate James C. Lucas.[94]

At Alcatraz, Capone's decline became increasingly evident as neurosyphilis progressively eroded his mental faculties,[13][95][96][97] his formal diagnosis of syphilis of the brain was made in February 1938.[98] He spent the last year of his Alcatraz sentence in the hospital section, confused and disoriented.[99] Capone completed his term in Alcatraz on January 6, 1939, and was transferred to the Federal Correctional Institution at Terminal Island in California to serve out his sentence for contempt of court.[100] He was paroled on November 16, 1939, after his wife Mae appealed to the court, based on his reduced mental capabilities diagnosed.[101][102]

Chicago aftermath

The main effect of Capone's conviction was that he ceased to be boss immediately on his imprisonment, but those involved in the jailing of Capone portrayed it as considerably undermining the city's organized crime syndicate. Capone's underboss, Frank Nitti took over as boss of the Outfit after he was released from prison in March 1932, having also been convicted of tax evasion charges.[103] Far from being smashed, the Outfit continued without being troubled by the Chicago police, but at a lower level and without the open violence that had marked Capone's rule. Organized crime in the city had a lower profile once Prohibition was repealed, already wary of attention after seeing Capone's notoriety bring him down, to the extent that there is a lack of consensus among writers about who was actually in control and who was a figurehead "front boss".[61]: 468–469, 517–518, 524–527, 538–541 [52] Prostitution, labor union racketeering, and gambling became moneymakers for organized crime in the city without incurring serious investigation. In the late 1950s, FBI agents discovered an organization led by Capone's former lieutenants reigning supreme over the Chicago underworld.[104]

Failing health and death

Due to his failing health, Capone was released from prison on November 16, 1939,[105] and referred to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for the treatment of paresis (caused by late-stage syphilis). Hopkins refused to admit him on his reputation alone, but Union Memorial Hospital accepted him. Capone was grateful for the compassionate care that he received and donated two Japanese weeping cherry trees to Union Memorial Hospital in 1939. A very sickly Capone left Baltimore on March 20, 1940, after a few weeks of inpatient and a few weeks of outpatient care, for Palm Island, Florida.[106][107][108] In 1942, after mass production of penicillin was started in the United States, Capone was one of the first American patients treated by the new drug.[109] Though it was too late for him to reverse the damage in his brain, it did slow down the progression of the disease.[101]

In 1946, his physician and a Baltimore psychiatrist examined him and concluded that Capone had the mentality of a 12-year-old child.[62] Capone spent the last years of his life at his mansion in Palm Island, Florida, spending time with his wife and grandchildren.[110] On January 21, 1947, Capone had a stroke. He regained consciousness and started to improve, but contracted bronchopneumonia. He suffered a cardiac arrest on January 22, and on January 25, surrounded by his family in his home, Capone died after his heart failed as a result of apoplexy.[111][112] His body was transported back to Chicago a week later and a private funeral was held.[113] He was originally buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Chicago. In 1950, Capone's remains, along with those of his father, Gabriele, and brother, Salvatore, were moved to Mount Carmel Cemetery in Hillside, Illinois.[114][115]

-

Capone's death certificate January 25, 1947

-

Capone's grave in Mount Carmel Cemetery, Hillside, Illinois

Victims

According to Guy Murchie Jr. from the Chicago Daily Tribune, 33 people died as a consequence of Al Capone's actions.

| Num | Victim | Date of death | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Joe Howard | May 7, 1923 | Tried hijacking Capone-Torrio beer and was a braggart.[116] |

| 2 | Dean O'Banion | November 10, 1924 | Ran North Side liquor business and declared, "To hell with the Sicilians!"[116] |

| 3 | Thomas Duffy | April 27, 1926 | Suspected of treachery by Capone.[116] |

| 4 | James J. Doherty | ||

| 5 | William H. McSwiggin | Happened to be with Duffy and Doherty that night.[116] | |

| 6 | Earl Hymie Weiss | October 11, 1926 | O'Banion's successor on the North Side and out to get Capone.[116] |

| 7 | John Costenaro | January 7, 1927 | Planning to testify against Capone in a conspiracy trial.[116] |

| 8 | Santo Celebron | ||

| 9 | Antonio Torchio | May 25, 1927 | Imported from New York to kill Capone.[116] |

| 10 | Frank Hitchcock | July 27, 1927 | Bootlegger enemy that Johnny Patton wanted out of the way.[116] |

| 11 | Anthony K. Russo | August 11, 1927 | Imported from St. Louis to kill Capone.[116] |

| 12 | Vincent Spicuzza | ||

| 13 | Samuel Valente | September 24, 1927 | Imported from Cleveland to kill Capone.[116] |

| 14 | Harry Fuller | January 18, 1928 | Hijacked Capone's beer and liquor.[116] |

| 15 | Joseph Cagiando | ||

| 16 | Joseph Fasso | ||

| 17 | "Diamond Joe" Esposito | March 21, 1928 | Did not want to support Capone on election day.[116] |

| 18 | Ben Newmark | April 23, 1928 | Tried to organize a rival gang; bodyguard of Capone tried to conceal his own treachery by carrying out the murder of Newmark.[116] |

| 19 | Francesco Uale (Frank Yale) | July 1, 1928 | Double-crossed Capone when serving as rum-running manager.[116] |

| 20 | Frank Gusenberg | February 14, 1929 | Were in the Moran gang hangout during the St. Valentine's Day Massacre.[116] |

| 21 | Pete Gusenberg | ||

| 22 | John May | ||

| 23 | Al Weinshank | ||

| 24 | James Clark | ||

| 25 | Adam Heyer | ||

| 26 | Dr. Reinhardt Schwimmer | ||

| 27 | Albert Anselmi | May 8, 1929 | Part of Joseph Giunta's plan to assassinate Capone.[116] |

| 28 | John Scalise | ||

| 29 | Joseph Giunta (Juno) | Was planning on assassinating Capone.[116] | |

| 30 | Frankie Marlow | June 24, 1929 | Refused to pay a debt of $250,000.[116] |

| 31 | Julius Rosenheim | February 1, 1930 | Informant to the police and newspapers on Capone's activities.[116] |

| 32 | Jack Zuta | August 1, 1930 | Spied on and double-crossed Capone.[116] |

| 33 | Joe Aiello | October 23, 1930 | Rival gang leader and ally of Bugs Moran.[116] |

In popular culture

Capone is one of the most notorious American gangsters of the 20th century and has been the major subject of numerous articles, books, and films. Particularly, from 1925 to 1929, shortly after Capone relocated to Chicago, he enjoyed status as the most notorious mobster in the country. Capone cultivated a certain image of himself in the media, that made him a subject of fascination.[117][118] His personality and character have been used in fiction as a model for crime lords and criminal masterminds ever since his death. The stereotypical image of a mobster wearing a blue pinstriped suit and tilted fedora is based on photos of Capone. His accent, mannerisms, facial construction, physical stature, and parodies of his name have been used for numerous gangsters in comics, movies, music, and literature.

Literature

- Capone is featured in a segment of Mario Puzo's The Godfather as an ally of New York mob boss Salvatore Maranzano in which he sends two "button men" at the mob boss' request to kill Don Vito Corleone; arriving in New York, the two men are intercepted and brutally killed by Luca Brasi, after which Don Corleone sends a message to Capone warning him not to interfere again, and Capone apparently capitulates.[119]

- Capone appears in Hergé's comic book Tintin in America, one of only two real-life characters in the entire The Adventures of Tintin series.[120]

- A reincarnated Capone is a major character in science fiction author Peter F. Hamilton's Night's Dawn Trilogy.

- Capone's grandniece Deirdre Marie Capone wrote a book titled Uncle Al Capone: The Untold Story from Inside His Family.[121]

- Al Capone is the inspiration for the central character of Tony Camonte in Armitage Trail's novel Scarface (1929),[122] which was adapted into the 1932 film. The novel was later adapted again in 1983 with the central character of Tony Montana.

- Jack Bilbo claimed to have been a bodyguard for Capone in his book Carrying a Gun for Al Capone (1932).[123]

- Al Capone is mentioned and met by the main character Moose in the book Al Capone Does My Shirts.

Film and television

Capone has been portrayed on screen by:

- Rod Steiger in Al Capone (1959)[124]

- Neville Brand in the TV series The Untouchables and again in the film The George Raft Story (1961)[124]

- José Calvo in Due mafiosi contro Al Capone (1966)[124]

- Jason Robards in The St. Valentine's Day Massacre (1967)[124]

- Ben Gazzara in Capone (1975)[124]

- Robert De Niro in The Untouchables (1987)[124]

- Ray Sharkey in The Revenge of Al Capone (1989)

- Eric Roberts in The Lost Capone (1990)

- Titus Welliver in Mobsters (1991)

- Bernie Gigliotti in The Babe (1992), in a brief scene in a Chicago nightclub during which Capone and his mentor Johnny Torrio, played by Guy Barile, meet the film's main character Babe Ruth, portrayed by John Goodman.

- William Forsythe in The Untouchables (1993–1994)

- William Devane in Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman, season 2, episode 7: "That Old Gang of Mine" (1994)

- F. Murray Abraham in Dillinger and Capone (1995)

- Anthony LaPaglia in Road to Perdition (2002), in a deleted scene[125]

- Julian Littman in Al's Lads (2002)

- Jon Bernthal in Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009)[126]

- Stephen Graham in Boardwalk Empire (2010–2014)

- Isaac Keoughan in Legends of Tomorrow (2016)[127]

- Michael Kotsohilis in The Making of the Mob: Chicago (2016)

- Cameron Gharaee in Timeless (2017)

- Tom Hardy in Capone (2020)

Actors playing characters based on Capone include:

- Wallace Beery as Louis "Louie" Scorpio in The Secret Six (1931)[124]

- Ricardo Cortez as Goldie Gorio in Bad Company (1931)[124]

- Paul Lukas as Big Fellow Maskal in City Streets (1931)[124]

- Edward Arnold as Duke Morgan in Okay, America! (1932)[124]

- Jean Hersholt as Samuel "Sam" Belmonte in The Beast of the City (1932)[124]

- Paul Muni as Antonio "Tony" Camonte in Scarface (1932)

- C. Henry Gordon as Nick Diamond in Gabriel Over the White House (1933)[124]

- John Litel as "Gat" Brady in Alcatraz Island (1937)[124]

- Barry Sullivan as Shubunka in The Gangster (1947)[124]

- Edward G. Robinson as Johnny Rocco in Key Largo (1948)

- Ralph Volkie as Big Fellow in The Undercover Man (1949)[124]

- Edmond O'Brien as Fran McCarg in Pete Kelly's Blues (1955)[124]

- B.S. Pully as Big Jule, an intimidating, gun-toting mobster from "East Cicero, Illinois" in the film adaptation of Guys and Dolls (1955), reprising the role that Pully had originated in the Broadway musical.[128]

- Lee J. Cobb as Rico Angelo in Party Girl (1958)[124]

- George Raft as Spats Colombo and Nehemiah Persoff as Little Bonaparte in Some Like It Hot (1959)[124]

- Cameron Mitchell as Boss Rojeck in My Favorite Year (1982)

- Harvey Atkin as "Al Koopone" (King Koopa) in The Super Mario Bros. Super Show episode "The Unzappables" (1989)

- Al Pacino as Alphonse "Big Boy" Caprice in Dick Tracy (1990)[124]

Music

- Prince Buster, Jamaican ska and rocksteady musician, had his first hit in the UK with the single "Al Capone" in 1967.[129]

- The British pop group Paper Lace's 1974 hit song "The Night Chicago Died" mentions that "a man named Al Capone, tried to make that town his own, and he called his gang to war, with the forces of the law".[130]

- British rock band Queen referenced Al Capone in the opening of their 1974 song "Stone Cold Crazy", which was covered in 1990 by the American rock band Metallica.[131]

- In 1979, The Specials, a UK ska revival group, reworked Prince Buster's track into their first single, "Gangsters", which featured the line "Don't call me Scarface!"

- Al Capone is referenced heavily in Prodigy's track "Al Capone Zone", produced by The Alchemist and featuring Keak Da Sneak.[132]

- "Al Capone" is a song by Michael Jackson. Jackson recorded the song during the Bad era (circa 1987), but it wasn't included on the album. The song was released in September 2012 in celebration of the album's 25th anniversary.

- Brazilian musician Raul Seixas has a song entitled "Al Capone", included in his 1973 debut album Krig-ha, Bandolo!.

- Multiple hip hop artists have adopted the name "Capone" for their stage names including: Capone, Mr. Capone-E and Al Kapone.

- The R&B Vocal Group The Fantastic Four recorded a song entitled "Alvin Stone:(the Birth & Death Of A Gangster)" in 1975 from their album of the same name. The main protagonist was a gangster with a name very similar to Al Capone [133]

Sports

- Fans of Serbian football club Partizan are using Al Capone's character as a mascot for one of their subgroups called "Alcatraz", named after a prison in which Al Capone served his sentence. Also, in honour of Capone, a graffiti representation of him exists in the center of Belgrade.

- Ultimate Fighting Championship heavyweight Nikita Krylov is nicknamed "Al Capone". Coincidentally, he had his first UFC win in Chicago.[134]

See also

- List of Depression-era outlaws

- The Mystery of Al Capone's Vaults

- Timeline of organized crime

- Al Capone bibliography

References

- ^ "the definition of al capone". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Schoenberg, Robert L. (1992). Mr. Capone. New York, New York: William Morrow and Company. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-688-12838-6. Archived from the original on 2015-12-09. Retrieved 2015-11-19.

- ^ Hendley, Nate (2010-06-21). Al Capone: Chicago's King of Crime. Five Rivers Chapmanry. ISBN 978-0-9866423-1-9.

- ^ Super User. "Al Capone, il gangster americano piu' famoso del mondo era di origini angresi". letrescimmiette.info. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Kobler, John (1971). Capone. Da Capo Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-306-80499-9.

- ^ Schoenberg, Robert J. (1992). Mr. Capone. New York: William Morrow & Co. pp. 98–99.

- ^ Crime Library Archived December 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Szalai, László (November 17, 2016). "Mysterious Adriatic Villa: It holds the greatest secrets, Al Capone was hiding his mother there". Telegraf.rs (in Serbian). Archived from the original on September 14, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ^ a b "Notorious Crime Files: Al Capone". The Biography Channel. Biography.com. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

- ^ Kobler, 27.

- ^ Balsamini, Dean (May 17, 2020). "Al Capone played semi-pro baseball in Brooklyn before turning to crime".

- ^ Kobler, 26.

- ^ a b c d e f The Five Families. MacMillan. p. [page needed]. Archived from the original on 2016-04-30. Retrieved 2015-11-19.

- ^ a b Kobler, 36.

- ^ Bardsley, Marilyn. "Scarface". Al Capone. Crime Library. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- ^ Kobler, 15.

- ^ "Mobsters and Gangsters from Al Capone to Tony Soprano", Life (2002).

- ^ Luciano J. Iorizzo (2003). Al Capone: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 26.

- ^ Bair, Deirdre (2016-10-25). Al Capone: His Life, Legacy, and Legend. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780385537162.

- ^ Get Capone: The Secret Plot That Captured America's Most Wanted, by Jonathan Eig. p17

- ^ Hood, Joel (2009-04-02). "Capone home on the market – Chicago Tribune Archives". Chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on April 5, 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ^ Bootleggers and Beer Barons of the Prohibition Era, by J. Anne Funderburg p.235

- ^ Bardsley, Marilyn. "Chicago". Al Capone. Crime Library. Archived from the original on 2008-05-31. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ^ Kobler, 37.

- ^ Bergreen, Laurence (1994). Capone: The Man and the Era. New York: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-0-684-82447-5.

- ^ Bergreen, pp 134–135

- ^ Bergreen, p. 138

- ^ a b "Hymie Weiss". Myalcaponemuseum.com. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: RyeMabee". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- ^ Sifakis, Carl, The Mafia Encyclopedia, 2nd ed., Checkmark Books (1999), p.362

- ^ Russo, Gus, The Outfit, Bloomsbury (2001), pp.39,40

- ^ Disasters and Tragic Events, edited by Mitchell Newton-Matza p.258

- ^ Walker, Jason (2009-07-07). "Templeton Rye of Templeton, Iowa". Heavy Table. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-04.

- ^ Russo, Gus, The Outfit, Bloomsbury (2001), p.37

- ^ a b "Al Capone's Couderay, Wisconsin Hideout Home for Sale; Asking Price $2.6M". CBS News. October 7, 2009. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ "Reputed Capone hideout sold to Wisconsin bank". CNN. 8 October 2009. Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "Al Capone's former Miami Beach mansion can be your escape from Canadian winter". nationalpost.com. November 8, 2019.

- ^ The Real Story: The Untouchables, Smithsonian Channel (2009 Documentary) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-17. Retrieved 2014-09-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Soup Kitchens" Archived 2018-11-09 at the Wayback Machine Social Security Online History Page.

- ^ "During the Great Depression Al Capone started one of the first "Soup Kitchens" for the unemployed". thevintagenews.com. June 6, 2016. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ Wendt, Lloyd; Herman Kogan (1953). Big Bill of Chicago. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill. pp. 232–244.

- ^ "Mayors". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Archived from the original on January 1, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ^ "Big Bill Thompson". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Archived from the original on December 3, 2011. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ^ Rainbow's End: Irish-Americans and the Dilemmas of Urban Machine Politics, by Steven P. Erie pp.102–126

- ^ The Irish Way: Becoming American in the Multiethnic City, by James R. Barrett note 32, 33, 109

- ^ White on Arrival: Italians, Race, Color, and Power in Chicago, 1890–1945 ... by Thomas A. Guglielmo pp.93–97

- ^ Sifakis, Carl, The Mafia Encyclopedia, 2nd ed., Checkmark Books (1999), pp.291, 292

- ^ Russo, Gus, The Outfit, Bloomsbury (2001), pp.38, 39

- ^ The Evening Independent – Jan 12, 1931, AP, Career of Chicago bomb king halted by bullets

- ^ The Afro American – Oct 12, 1929, Chicargo (ANP)Police Named In Granady Killing,

- ^ The Outfit: The Role Of Chicago's Underworld In The Shaping Of Modern America. Gus Russo

- ^ a b Kass, John (March 7, 2013). "Cermak's death offers lesson in Chicago Way". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "George 'Bugs' Moran". Bugs Moran. Archived from the original on September 3, 2015.

- ^ My Al Capone Museum Archived 2014-07-06 at the Wayback Machine "Vincent 'The Schemer' Drucci" Archived 2014-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, Mario Gomes, accessed 2/7/14

- ^ "Slay doctor in massacre". Chicago Daily Tribune. February 15, 1929. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "Trace killers; lid on city". Chicago Daily Tribune. February 16, 1929. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Bergreen, p. 418

- ^ Iorizzo, Luciano J. (2003). Al Capone: A Biography. Greenwood. pp. 49.

al capone baseball bat.

- ^ a b c d Bair, Deirdre (2016-10-25). Al Capone: His Life, Legacy, and Legend. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780385537162.

- ^ a b Hazelgrove, William Elliott (2017-09-15). Al Capone and the 1933 World's Fair: The End of the Gangster Era in Chicago. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 46–47. ISBN 9781442272279.

- ^ a b c Collins, Max Allan; Schwartz, A. Brad (2018). Scarface and the Untouchable: Al Capone, Eliot Ness, and the Battle for Chicago (1st ed.). New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-244194-2. Archived from the original on 2020-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- ^ a b "Al Capone". Federal Bureau of Investigations. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Schoenberg, Robert J (1992). Mr Capone. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company, Inc. p. 238. ISBN 0-688-08941-0.

- ^ "Defending Al Capone". The Marshall Project. Archived from the original on 2018-08-27. Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- ^ Luisa Yanez, The Miami Herald (2010-09-27). "Gangster Al Capone's 1930 trial to return to Miami court – Sun Sentinel". Articles.sun-sentinel.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ^ Reading Eagle – Sep 17, 1930, Gang leaders face arrest,

- ^ Al Capone: A Biography By Luciano J. Iorizzo p62-63

- ^ The Pittsburgh Press – Feb 27, 1931

- ^ Bergreen p. 419

- ^ Bryson, Bill (2013). One Summer, America, 1927. New York: Random House. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-375-43432-7.

- ^ Capone: The Man and the Era – Page 224

- ^ Al Capone: Chicago's King of Crime, by Nate Hendley, p. 108

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hoffman, Dennis (2010). Scarface Al and the Crime Crusaders: Chicago's Private War Against Capone. Chicago: Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 159–164. ISBN 978-0-8093-3004-1.

- ^ Okrent, Daniel (2010). Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. New York: Scribner. pp. 136, 345. ISBN 978-0-7432-7704-4.

- ^ "Al Capone's tax trial and downfall". Myalcaponemuseum.com. Archived from the original on 2014-08-11. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ^ "Al Capone Trial (1931): An Account by Douglas O. Linder (2011)". Law2.umkc.edu. Archived from the original on 2014-08-19. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ^ Al Capone Trial: A Chronology Daniel M. Porazzo. Retrieved 30 June 2014. Archived October 31, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Iorizzo, Luciano J. (2003). Al Capone: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 81-82. ISBN 978-0-313-32317-1 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Al Capone - American criminal". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2019-06-05. Retrieved 2020-01-11.

- ^ Kinsley, Philip (October 19, 1931). "U.S. jury convicts Capone". Chicago Sunday Tribune. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "Capone convicted of tax evasion". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. October 18, 1931. p. 1.

- ^ Hackler, Victor (October 24, 1931). "Capone sentenced 11 years, fined $50,000". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. p. 1.

- ^ "Capone in jail; prison next". Chicago Sunday Tribune. October 25, 1931. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Brennan, Ray (October 25, 1931). "Capone kept until Monday for appeal". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. p. 1.

- ^ "Visitors to the Court-Historic Trials". US District Court-Northern District of Illinois. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2011-02-10.

- ^ Linder, Douglas O. "Selected Documents: Jury Verdict Form (October 17, 1931)". Al Capone Trial. University of Missouri–Kansas City. Archived from the original on August 27, 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- ^ Bergreen, p. 484

- ^ Capone v. United States, 56 F.2d 927 (7th Cir. 1932).

- ^ Bergreen, pp. 486–487

- ^ Capone v. United States, 56 F.2d 927 (1931), cert. denied, 286 U.S. 553, 76 L.Ed. 1288, 52 S.Ct. 503; (1932); United States v. Capone, 93 F.2d 840 (1937), cert. denied, 303 U.S. 651, 82 L.Ed. 1112, 58 S.Ct. 750 (1938).

- ^ Bergreen, Laurence, Capone: The Man and the Era, p. 516.

- ^ a b c Bergreen, pp. 511–514

- ^ Bergreen, pp. 519–521

- ^ "Al Capone Knifed in Prison Tussle". The Free Lance-Star. June 24, 1936. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ^ "First Prisoners Arrive at Alcatraz Prison (Likely Including Al Capone)". Timelines.com. 1934-08-11. Archived from the original on 2010-12-01. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ^ Sifakis, Carl. The Mafia Encyclopedia. New York: Da Capo Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8160-5694-3

- ^ "Al Capone at Alcatraz". Ocean View Publishing. 1992. Archived from the original on 2010-11-19. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

- ^ Markel, Howard (25 Jan 2017). "The infectious disease that sprung Al Capone from Alcatraz". PBS News. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ Al Capone – The Final Chapter Archived 2008-05-31 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ J. Campbell Bruce, Escape from Alcatraz, Random House Digital, Inc. (2005), p 32.

- ^ a b Smee, Taryn (27 August 2018). "Legendary Gangster Al Capone was one of the First Recipients of Penicillin in History". The Vintage News. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ Webley, Kayla (April 28, 2010). "Top 10 Parolees". Time.com. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ Eghigian, Mars. After Capone: The Life and World of Chicago Mob Boss Frank "The Enforcer" Nitti. Naperville, Ill.: Cumberland House Publishing, 2006. ISBN 1-58182-454-8

- ^ The Chicago Outfit, John J. Binder, chapter four

- ^ ""Scarface Al" Capone Released by Government". Wausau Daily Herald. November 16, 1939. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Sandler, Gilbert (30 August 1994). "Al Capone's hide-out". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ Perl, Larry (26 March 2012). "For Union Memorial, Al Capone's tree keeps on giving". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ Slade, Fred (10 April 2014). "Medstar Union Memorial celebrates Capone Cherry Tree blooming". Abc2News. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ The first use of penicillin in the United States was on March 14, 1942, for a patient with streptococcal sepsis.

- ^ John J. Binder, The Chicago Outfit, Arcadia Publishing (2003), pp 41–42.

- ^ "Al Capone dies in Florida villa". Chicago Sunday Tribune. Associated Press. January 26, 1947. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "Capone Dead At 48. Dry Era Gang Chief". The New York Times. Associated Press. 2009-04-02. Archived from the original on 28 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

Al Capone, ex-Chicago gangster and prohibition era crime leader, died in his home here tonight.

- ^ "Al Capone's body is returned to Chicago in secrecy for burial, 1947". February 1, 1947. Archived from the original on January 11, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ "Mount Carmel". Oldghosthome.com. Archived from the original on 2004-09-03.

- ^ Wilson, Scott (2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed. McFarland. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-1-4766-2599-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Murchie, Guy, Jr. (9 February 1936). "Capone's Decade of Death". Chicago Daily Tribune. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Al Capone: The story behind his rise and fall | The Mob Museum". The Mob Museum. 2016-07-06. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- ^ "The 17 most notorious mobsters from Chicago". Time Out Chicago. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- ^ Puzo, Mario (1969). The Godfather. pp. 214–217. ISBN 0-7493-2468-6.

- ^ Ruas, Pierre Assouline ; translated by Charles (2009). Hergé : the man who created Tintin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539759-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Capone, Deirdre Marie. Uncle Al Capone – The Untold Story from Inside His Family. Amazon.com. ISBN 978-0-9828451-0-3. Archived from the original on 2012-04-21. Retrieved 2012-04-13.

- ^ Trail, Armitage (1930). Scarface (1ST ed.). D.J. Clode. ASIN B00085TELI.

- ^ Bilbo, Jack (1932). Carrying a Gun for Al Capone. London & New York: Putnam.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Newman, Kim (1997). Hardy, Phil (ed.). The BFI companion to crime. Cassell. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-304-33215-1. OCLC 247004388.

- ^ "Video Beat: 'Perdition' exudes a hellish beauty". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. 2003-03-01. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ Loewenstein, Lael (2009-05-20). "Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian". Variety. Archived from the original on 2009-05-25. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ Schedeen, Jesse (December 8, 2016). "DC's Legends of Tomorrow: "The Chicago Way" Review". IGN. J2 Global. Archived from the original on December 9, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ "B.S. Pully, Comedian, 61, Dies; Was Big Jule in 'Guys and Dolls'" Archived 2018-06-24 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. 1972-01-08. p. 32.

- ^ "Prince Buster, Al Capone". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ^ John D. McKinnon And Corey Boles (September 16, 2012). "Susan Rice: Libya Protests 'Hijacked' by Extremists". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ "Stone Cold Crazy – Queen". All Music. Archived from the original on 2016-05-01. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ "Al Capone Zone | Alchemist Song". New.music.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ^ "YouTube". Youtube.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ "Nikita "Al Capone" Krylov's profile". Sherdog.com. 1992-03-07. Archived from the original on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

Further reading

- Capone, Deirdre Marie. Uncle Al Capone: The Untold Story from Inside His Family. Recap Publishing LLC, 2010. ISBN 978-0-982-84510-3.

- Collins, Max Allan, and A. Brad Schwartz. Scarface and the Untouchable: Al Capone, Eliot Ness, and the Battle for Chicago. New York: William Morrow, 2018. ISBN 978-0062441942.

- Helmer, William J. Al Capone and His American Boys: Memoirs of a Mobster's Wife. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-253-35606-2.

- Hoffman Dennis E. Scarface Al and the Crime Crusaders: Chicago's Private War Against Capone. Southern Illinois University Press; 1st edition (November 24, 1993). ISBN 978-0-8093-1925-1.

- Kobler, John. Capone: The Life and Times of Al Capone. New York: Da Capo Press, 2003. ISBN 0-306-81285-1.

- MacDonald, Alan. Dead Famous: Al Capone and His Gang. Scholastic.

- Michaels, Will. "Al Capone in St. Petersburg, Florida" in Hidden History of St. Petersburg. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2016. ISBN 9781625858207.

- Pasley, Fred D. Al Capone: The Biography of a Self-Made Man. Garden City, New York: Garden City Publishing Co., 2004. ISBN 1-4179-0878-5.

- Schoenberg, Robert J. Mr. Capone. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1992. ISBN 0-688-12838-6.

External links

- Mario Gomes' site on everything related to Al Capone

- South Beach Magazine The Un-Welcomed Visitor: Al Capone in Miami. (with photos)

- FBI files on Al Capone

- Little Chicago: Capone in Johnson City, Tennessee

- Al Capone at the Crime Library

- Template:Worldcat id

- Al Capone on IMDb

- Al Capone

- 1899 births

- 1947 deaths

- American businesspeople convicted of crimes

- American mob bosses

- American mobsters of Italian descent

- American people convicted of tax crimes

- American people of Campanian descent

- American Roman Catholics

- American bootleggers

- Catholics from Illinois

- Catholics from New York (state)

- Chicago Outfit bosses

- Chicago Outfit mobsters

- Criminals of Chicago

- Deaths from bleeding

- Deaths from bronchopneumonia

- Deaths from cardiac arrest

- Deaths from cerebrovascular disease

- Depression-era mobsters

- Disease-related deaths in Florida

- Five Points Gang

- Inmates of Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary

- People from Cicero, Illinois

- People from Park Slope

- Prohibition-era gangsters