Measles

| Measles | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Morbilli, rubeola, red measles, English measles[1][2] |

| |

| A child showing a day-four measles rash | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, cough, runny nose, inflamed eyes, rash[3][4] |

| Complications | Pneumonia, seizures, encephalitis, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis[5] |

| Usual onset | 10–12 days after exposure[6][7] |

| Duration | 7–10 days[6][7] |

| Causes | Measles virus[3] |

| Prevention | Measles vaccine[6] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[6] |

| Frequency | 20 million per year[3] |

| Deaths | 73,400 (2015)[8] |

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by the measles virus.[3][9] Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days.[6][7] Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than 40 °C (104.0 °F), cough, runny nose, and inflamed eyes.[3][4] Small white spots known as Koplik's spots may form inside the mouth two or three days after the start of symptoms.[4] A red, flat rash which usually starts on the face and then spreads to the rest of the body typically begins three to five days after the start of symptoms.[4] Common complications include diarrhea (in 8% of cases), middle ear infection (7%), and pneumonia (6%).[5] Less commonly seizures, blindness, or inflammation of the brain may occur.[6][5] Other names include morbilli, rubeola, red measles, and English measles.[1][2] Rubella, which is sometimes called German measles, and roseola are different diseases caused by unrelated viruses.[10]

Measles is an airborne disease which spreads easily through the coughs and sneezes of infected people.[6] It may also be spread through contact with saliva or nasal secretions.[6] Nine out of ten people who are not immune and share living space with an infected person will be infected.[5] People are infectious to others from four days before to four days after the start of the rash.[5] Most people do not get the disease more than once.[6] Testing for the measles virus in suspected cases is important for public health efforts.[5]

The measles vaccine is effective at preventing the disease, and is often delivered in combination with other vaccines.[6] Vaccination resulted in a 75% decrease in deaths from measles between 2000 and 2013, with about 85% of children worldwide being currently vaccinated.[6] Once a person has become infected, no specific treatment is available,[6] but supportive care may improve outcomes.[6] This may include oral rehydration solution (slightly sweet and salty fluids), healthy food, and medications to control the fever.[6][7] Antibiotics may be used if a secondary bacterial infection such as bacterial pneumonia occurs.[6] Vitamin A supplementation is also recommended in the developing world.[6]

Measles affects about 20 million people a year,[3] primarily in the developing areas of Africa and Asia.[6] It is one of the leading vaccine-preventable disease causes of death.[11][12] In 1980, 2.6 million people died of it,[6] and in 1990, 545,000 died; by 2014, global vaccination programs had reduced the number of deaths from measles to 73,000.[8][13] Rates of disease and deaths, however, increased in 2017 due to a decrease in immunization.[14] The risk of death among those infected is about 0.2%,[5] but may be up to 10% in people with malnutrition.[6] Most of those who die from the infection are less than five years old.[6] Measles is not believed to affect other animals.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms typically begin 10–14 days after exposure.[15][16] The classic symptoms include a four-day fever (the 4 D's) and the three C's—cough, coryza (head cold, fever, sneezing), and conjunctivitis (red eyes)—along with fever and rashes.[17] Fever is common and typically lasts for about one week; the fever seen with measles is often as high as 40 °C (104 °F).[18]

Koplik's spots seen inside the mouth are diagnostic for measles, but are temporary and therefore rarely seen.[17] Koplik spots are small white spots that are commonly seen on the inside of the cheeks opposite the molars.[16] Recognizing these spots before a person reaches their maximum infectiousness can help reduce the spread of the disease.[19]

The characteristic measles rash is classically described as a generalized red maculopapular rash that begins several days after the fever starts. It starts on the back of the ears and, after a few hours, spreads to the head and neck before spreading to cover most of the body, often causing itching. The measles rash appears two to four days after the initial symptoms and lasts for up to eight days. The rash is said to "stain", changing color from red to dark brown, before disappearing.[20] Overall, measles usually resolves after about three weeks.[18]

Complications

Complications of measles are relatively common, ranging from mild ones such as diarrhea to serious ones such as pneumonia (either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia), bronchitis (either direct viral bronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis), otitis media,[21] acute brain inflammation[22] (and very rarely subacute sclerosing panencephalitis),[23] and corneal ulceration (leading to corneal scarring).[24] In addition, measles can suppress the immune system for weeks to months, and this can contribute to bacterial superinfections like otitis media and bacterial pneumonia.[25][26][27]

The death rate in the 1920s was around 30% for measles pneumonia.[28] People who are at high risk for complications are infants and children aged less than 5 years[29]; adults aged over 20 years[29]; pregnant women[29]; people with compromised immune systems, such as from leukemia, HIV infection or innate immunodeficiency;[29][30] and those who are malnourished[29] or have vitamin A deficiency.[29][31] Complications are usually more severe in adults who catch the virus.[32] Between 1987 and 2000, the case fatality rate across the United States was 3 measles-attributable deaths per 1000 cases, or 0.3%.[33] In underdeveloped nations with high rates of malnutrition and poor healthcare, fatality rates have been as high as 28%.[33] In immunocompromised persons (e.g., people with AIDS) the fatality rate is approximately 30%.[34] Even in previously healthy children, measles can cause serious illness requiring hospitalization.[30] One out of every 1,000 measles cases progresses to acute encephalitis, which often results in permanent brain damage.[30] One or two out of every 1,000 children who become infected with measles will die from respiratory and neurological complications.[30]

Cause

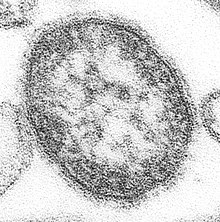

Measles is caused by the measles virus, a single-stranded, negative-sense, enveloped RNA virus of the genus Morbillivirus within the family Paramyxoviridae.[35]

The virus is highly contagious and is spread by coughing and sneezing via close personal contact or direct contact with secretions.[36] It can live for up to two hours in that airspace or nearby surfaces.[15][36] Measles is so contagious that if one person has it, 90% of nearby non-immune people will also become infected.[15] Humans are the only natural hosts of the virus, and no other animal reservoirs are known to exist.[15]

Risk factors for measles virus infection include immunodeficiency caused by HIV or AIDS,[37] immunosuppression following receipt of an organ or a stem cell transplant,[38] alkylating agents, or corticosteroid therapy, regardless of immunization status;[29] travel to areas where measles commonly occurs or contact with travelers from such an area;[29] and the loss of passive, inherited antibodies before the age of routine immunization.[39]

Pathophysiology

Once the measles virus gets onto the mucosa, it infects the epithelial cells in the trachea or bronchi.[40][41] Measles virus uses a protein on its surface called hemagglutinin (H protein), to bind to a target receptor on the host cell, which could be CD46, which is expressed on all nucleated human cells, CD150, aka signaling lymphocyte activation molecule or SLAM, which is found on immune cells like B or T cells, and antigen-presenting cells, or nectin-4, a cellular adhesion molecule.[40][42] Once bound, the fusion, or F protein helps the virus fuse with the membrane and ultimately get inside the cell.[40] The virus is a single-stranded negative-sense RNA virus meaning it first has to be transcribed by RNA polymerase into a positive-sense mRNA strand.[40]

After that it is ready to be translated into viral proteins, wrapped in the cell’s lipid envelope, and sent out of the cell as a newly made virus.[43] Within days, the measles virus spreads through local tissue and is picked up by dendritic cells and alveolar macrophages, and carried from that local tissue in the lungs to the local lymph nodes.[40][41] From there it continues to spread, eventually getting into the blood and spreading to more lung tissue, as well as other organs like the intestines and the brain.[15][40]

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of measles requires a history of fever of at least three days, with at least one the following symptoms: cough, coryza, or conjunctivitis. Observation of Koplik's spots is also diagnostic.[19] Laboratory confirmation is however strongly recommended.[44]

Laboratory testing

Laboratory diagnosis of measles can be done with confirmation of positive measles IgM antibodies or isolation of measles virus RNA from respiratory specimens.[45] For people unable to have their blood drawn, saliva can be collected for salivary measles-specific IgA testing.[46] Positive contact with other people known to have measles adds evidence to the diagnosis. Any contact with an infected person, including semen through sex, saliva, or mucus, can cause infection.[citation needed]

Prevention

Mothers who are immune to measles pass antibodies to their children while they are still in the womb, especially if the mother acquired immunity though infection rather than vaccination.[15][39] Such antibodies will usually give newborn infants some immunity against measles, but these antibodies are gradually lost over the course of the first nine months of life.[16][39] Infants under one year of age whose maternal anti-measles antibodies have disappeared become susceptible to infection with the measles virus.[39]

In developed countries, it is recommended that children be immunized against measles at 12 months, generally as part of a three-part MMR vaccine (measles, mumps, and rubella). The vaccine is generally not given before this age because such infants respond inadequately to the vaccine due to an immature immune system.[39] A second dose of the vaccine is usually given to children between the ages of four and five, to increase rates of immunity. Vaccination rates have been high enough to make measles relatively uncommon. Adverse reactions to vaccination are rare, with fever and pain at the injection site being the most common. Life-threatening adverse reactions occur in less than one per million vaccinations (<0.0001%).[47]

In developing countries where measles is common, the World Health Organization recommend two doses of vaccine be given, at six and nine months of age. The vaccine should be given whether the child is HIV-infected or not.[48] The vaccine is less effective in HIV-infected infants than in the general population, but early treatment with antiretroviral drugs can increase its effectiveness.[49] Measles vaccination programs are often used to deliver other child health interventions as well, such as bed nets to protect against malaria, antiparasite medicine and vitamin A supplements, and so contribute to the reduction of child deaths from other causes.[50]

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has long recommended that all adult international travelers who do not have positive evidence of previous measles immunity receive two doses of MMR vaccine before traveling.[51] Despite this, a retrospective study of pre-travel consultations with prospective travelers at United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-associated travel clinics found that of the 16% of adult travelers who were considered eligible for vaccination, only 47% underwent vaccination during the consultation; of these, patient refusal accounted for nearly half (48%), followed by healthcare provider decisions (28%) and barriers in the health system (24%).[52]

Treatment

There is no specific antiviral treatment if measles develops.[36] Instead the medications are generally aimed at treating superinfections, maintaining good hydration with adequate fluids, and pain relief.[36] Some groups, like young children and the severely malnourished, are also given vitamin A, which act as an immunomodulator that boosts the antibody responses to measles and decreases the risk of serious complications.[36][53]

Medications

Treatment addresses symptoms, with ibuprofen or paracetamol to reduce fever and pain and, if required, a fast-acting medication to dilate the airways for cough. As for aspirin, some research has suggested a correlation between children who take aspirin and the development of Reye syndrome.[54][55][56][57][58][59]

The use of vitamin A during treatment is recommended to decrease the risk of blindness;[60] however, it does not prevent or cure the disease.[61] A systematic review of trials into its use found no reduction in overall mortality, but it did reduce mortality in children aged under two years.[62] It is unclear if zinc supplementation in children with measles affects outcomes.[63]

Complications

Complications may include pneumonia, ear infections, bronchitis (either viral bronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis), and brain inflammation.[64] Brain inflammation from measles has a mortality rate of 15%. While there is no specific treatment for brain inflammation from measles, antibiotics are required for bacterial pneumonia, sinusitis, and bronchitis that can follow measles.

Prognosis

Most people survive measles, though in some cases, complications may occur. Possible consequences of measles virus infection include bronchitis, sensorineural hearing loss,[35] and—in about 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 300,000 cases[65]—panencephalitis, which is usually fatal.[66] Acute measles encephalitis is another serious risk of measles virus infection. It typically occurs two days to one week after the measles rash breaks out and begins with very high fever, severe headache, convulsions and altered mentation. A person with measles encephalitis may become comatose, and death or brain injury may occur.[67]

Epidemiology

This section needs to be updated. (February 2019) |

Measles is extremely infectious and its continued circulation in a community depends on the generation of susceptible hosts by birth of children. In communities that generate insufficient new hosts the disease will die out. This concept was first recognized in measles by Bartlett in 1957, who referred to the minimum number supporting measles as the critical community size (CCS).[68] Analysis of outbreaks in island communities suggested that the CCS for measles is around 250,000.[69] To achieve herd immunity, more than 95% of the community must be vaccinated due to the ease with which measles is transmitted from person to person.[18] The disease was eliminated from the Americas in 2016.[70]

In 2011, the WHO estimated that 158,000 deaths were caused by measles. This is down from 630,000 deaths in 1990.[71] As of 2018, measles remains a leading cause of vaccine-preventable deaths in the world.[11][72] In developed countries, death occurs in one to two cases out of every 1,000 (0.1–0.2%).[73] In populations with high levels of malnutrition and a lack of adequate healthcare, mortality can be as high as 10%. In cases with complications, the rate may rise to 20–30%.[74] In 2012, the number of deaths due to measles was 78% lower than in 2000 due to increased rates of immunization among UN member states.[18]

| WHO-Region | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2005 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Region | 1,240,993 | 481,204 | 520,102 | 316,224 | 71,574 |

| Region of the Americas | 257,790 | 218,579 | 1,755 | 66 | 19,898 |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 341,624 | 59,058 | 38,592 | 15,069 | 28,031 |

| European Region | 851,849 | 234,827 | 37,421 | 37,332 | 16,899 |

| South-East Asia Region | 199,535 | 224,925 | 61,975 | 83,627 | 112,418 |

| Western Pacific Region | 1,319,640 | 155,490 | 176,493 | 128,016 | 213,366 |

| Worldwide | 4,211,431 | 1,374,083 | 836,338 | 580,287 | 462,186 |

Even in countries where vaccination has been introduced, rates may remain high. Measles is a leading cause of vaccine-preventable childhood mortality. Worldwide, the fatality rate has been significantly reduced by a vaccination campaign led by partners in the Measles Initiative: the American Red Cross, the United States CDC, the United Nations Foundation, UNICEF and the WHO. Globally, measles fell 60% from an estimated 873,000 deaths in 1999 to 345,000 in 2005.[81] Estimates for 2008 indicate deaths fell further to 164,000 globally, with 77% of the remaining measles deaths in 2008 occurring within the Southeast Asian region.[82]

Five out of six WHO regions have set goals to eliminate measles, and at the 63rd World Health Assembly in May 2010, delegates agreed on a global target of a 95% reduction in measles mortality by 2015 from the level seen in 2000, as well as to move towards eventual eradication. However, no specific global target date for eradication has yet been agreed to as of May 2010.[83][84]

Europe

In 2013–14, there were almost 10,000 cases in 30 European countries. Most cases occurred in unvaccinated individuals and over 90% of cases occurred in the five European nations: Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Romania, and United Kingdom.[18] Between October 2014 and March 2015, a measles outbreak in the German capital of Berlin resulted in at least 782 cases.[85] In 2017 numbers continued to increase in Europe to 21,315 cases, with 35 deaths.[86]

Americas

As a result of widespread vaccination, the disease was declared eliminated from the Americas in 2016.[70] It, however, occurred again in 2017 and 2018 in this region.[87]

United States

Before immunization in the United States, between three and four million cases occurred each year.[5] The United States was declared free of circulating measles in 2000, with 911 cases from 2001 to 2011. In 2014 the CDC said endemic measles, rubella, and congenital rubella syndrome had not returned to the United States.[88] Occasional measles outbreaks persist, however, because of cases imported from abroad, of which more than half are the result of unvaccinated U.S. residents who are infected abroad and infect others upon return to the United States.[88] The CDC continues to recommend measles vaccination throughout the population to prevent outbreaks like these.[89]

In 2014, an outbreak was initiated in Ohio when two unvaccinated Amish men harboring asymptomatic measles returned to the United States from missionary work in the Philippines.[90] Their return to a community with low vaccination rates led to an outbreak that rose to include a total of 383 cases across nine counties.[90] Of the 383 cases, 340 (89%) occurred in unvaccinated individuals.[90]

From January 4 to April 2, 2015, there were 159 cases of measles reported to the CDC. Of those 159 cases, 111 (70%) were determined to have come from an earlier exposure in late December 2014. This outbreak was believed to have originated from the Disneyland theme park in California. The Disneyland outbreak was held responsible for the infection of 147 people in seven U.S. states as well as Mexico and Canada, the majority of which were either unvaccinated or had unknown vaccination status.[91] Of the cases 48% were unvaccinated and 38% were unsure of their vaccination status.[92] The initial exposure to the virus was never identified.

In 2015, a U.S. woman in Washington state died of pneumonia, as a result of measles. She was the first fatality in the US from measles since 2003.[93] The woman had been vaccinated for measles and was taking immunosuppressive drug for another condition. The drugs suppressed the woman's immunity to measles, and the woman became infected with measles; she did not develop a rash, but contracted pneumonia, which caused her death.[94]

In June 2017, the Maine Health and Environmental Testing Laboratory confirmed a case of measles in Franklin County. This instance marks the first case of measles in 20 years for the state of Maine.[95] In 2018 one case occurred in Portland, Oregon, with 500 people exposed; 40 of them lacked immunity to the virus and were being monitored by county health officials as of July 2, 2018.[96] There were 273 cases of measles reported throughout the United States in 2018,[97] including an outbreak in Brooklyn with more than 200 reported cases from October 2018 to February 2019. The outbreak was tied with population density of the Orthodox Jewish community, with the initial exposure from an unvaccinated child that caught measles while visiting Israel.[98][99]

In January and February 2019, Washington state reported an outbreak of at least 58 confirmed cases of measles, most within Clark County, which has a higher rate of vaccination exemptions compared to the rest of the state; nearly one in four kindergartners in Clark did not receive vaccinations, according to state data.[98] This led state governor Jay Inslee to declare a state of emergency, and the state's congress to introduce legislation to disallow vaccination exemption for personal or philosophical reasons.[100] The resurgence of measles in the region was caused by parents choosing not to have their children vaccinated.[101][102][103][104]

Brazil

The spread of measles had been interrupted in Brazil as of 2016, with the last known case twelve months earlier.[105] This last case was in the state of Ceará.[106]

Brazil won a measles elimination certificate by the Pan American Health Organization in 2016, but the Ministry of Health has proclaimed that the country has struggled to keep this certificate, since two outbreaks had already been identified in 2018, one in the state of Amazonas and another one in Roraima, in addition to cases in other states (Rio de Janeiro, Rio Grande do Sul, Pará, São Paulo and Rondônia), totaling 1053 confirmed cases until August 1, 2018.[107][108] In these outbreaks, and in most other cases, the contagion was related to the importation of the virus, especially from Venezuela.[107] This was confirmed by the genotype of the virus (D8) that was identified, which is the same that circulates in Venezuela.[108]

Southeast Asia

In the Vietnamese measles epidemic in spring of 2014, an estimated 8,500 measles cases were reported as of April 19, with 114 fatalities;[109] as of May 30, 21,639 suspected measles cases had been reported, with 142 measles-related fatalities.[110]

In the Naga Self-Administered Zone in a remote northern region of Myanmar, at least 40 children died during a measles outbreak in August 2016 that was probably caused by lack of vaccination in an area of poor health infrastructure.[111][112]

History

Estimates based on modern molecular biology place the emergence of measles as a human disease sometime after 500 AD[113] (the former speculation that the Antonine Plague of 165–180 AD was caused by measles is now discounted). The first systematic description of measles, and its distinction from smallpox and chickenpox, is credited to the Persian physician Rhazes (860–932), who published The Book of Smallpox and Measles.[114] Given what is now known about the evolution of measles, Rhazes' account is remarkably timely, as recent work that examined the mutation rate of the virus indicates the measles virus emerged from rinderpest (cattle plague) as a zoonotic disease between 1100 and 1200 AD, a period that may have been preceded by limited outbreaks involving a virus not yet fully acclimated to humans.[113] This agrees with the observation that measles requires a susceptible population of >500,000 to sustain an epidemic, a situation that occurred in historic times following the growth of medieval European cities.[69]

Measles is an endemic disease, meaning it has been continually present in a community, and many people develop resistance. In populations not exposed to measles, exposure to the new disease can be devastating. In 1529, a measles outbreak in Cuba killed two-thirds of those natives who had previously survived smallpox. Two years later, measles was responsible for the deaths of half the population of Honduras, and it had ravaged Mexico, Central America, and the Inca civilization.[116]

Between roughly 1855 and 2005, measles has been estimated to have killed about 200 million people worldwide.[117] Measles killed 20 percent of Hawaii's population in the 1850s.[118] In 1875, measles killed over 40,000 Fijians, approximately one-third of the population.[119] In the 19th century, the disease killed 50% of the Andamanese population.[120] Seven to eight million children are thought to have died from measles each year before the vaccine was introduced.[18]

In 1954, the virus causing the disease was isolated from a 13-year-old boy from the United States, David Edmonston, and adapted and propagated on chick embryo tissue culture.[121] To date, 21 strains of the measles virus have been identified.[122] While at Merck, Maurice Hilleman developed the first successful vaccine.[123] Licensed vaccines to prevent the disease became available in 1963.[124] An improved measles vaccine became available in 1968.[125] Measles as an endemic disease was eliminated from the United States in 2000, but continues to be reintroduced by international travelers.[126]

Society and culture

German anti-vaccination campaigner and HIV/AIDS denialist[127] Stefan Lanka posed a challenge on his website in 2011, offering a sum of €100,000 for anyone who could scientifically prove that measles is caused by a virus and determine the diameter of the virus.[128] He posits that the illness is psychosomatic and that the measles virus does not exist. When provided with overwhelming scientific evidence from various medical studies by German physician David Bardens, Lanka did not accept the findings, forcing Bardens to appeal in court. The legal case ended with the ruling that Lanka was to pay the prize.[85][129] The case received wide international coverage that prompted many to comment on it, including neurologist, well-known skeptic and science-based medicine advocate Steven Novella, who called Lanka "a crank".[130] As outbreaks easily occur in under-vaccination populations, the disease is seen as a test of sufficient vaccination within a population.[131]

Names

Other names include morbilli, rubeola, red measles, and English measles.[1][2]

Research

In May 2015, the journal Science, published a report in which researchers found that the measles infection can leave a population at increased risk for mortality from other diseases for two to three years.[132][133]

A specific drug treatment for measles, ERDRP-0519, has shown promising results in animal studies, but has not yet been tested in humans.[134][135][136]

References

- ^ a b c Milner, Danny A. (2015). Diagnostic Pathology: Infectious Diseases E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 24. ISBN 9780323400374. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Stanley, Jacqueline (2002). Essentials of Immunology & Serology. Cengage Learning. p. 323. ISBN 978-0766810648. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Caserta, MT, ed. (September 2013). "Measles". Merck Manual Professional. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Measles (Rubeola) Signs and Symptoms". cdc.gov. November 3, 2014. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Atkinson, William (2011). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (12 ed.). Public Health Foundation. pp. 301–23. ISBN 9780983263135. Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Measles Fact sheet N°286". who.int. November 2014. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Conn's Current Therapy 2015. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2014. p. 153. ISBN 9780323319560. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Measles (Red Measles, Rubeola)". Dept of Health, Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Marx, John A. (2010). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 1541. ISBN 9780323054720. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Kabra, SK; Lodhra, R (14 August 2013). "Antibiotics for preventing complications in children with measles". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD001477. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001477.pub4. PMID 23943263.

- ^ "Despite the availability of a safe, effective and inexpensive vaccine for more than 40 years, measles remains a leading vaccine-preventable cause of childhood deaths" (PDF). Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Measles cases spike globally due to gaps in vaccination coverage". WHO. 29 November 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "Pinkbook Measles Epidemiology of Vaccine Preventable Diseases". CDC. 15 November 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ a b c "Measles". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. January 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ a b Biesbroeck L, Sidbury R (November 2013). "Viral exanthems: an update". Dermatologic Therapy. 26 (6): 433–38. doi:10.1111/dth.12107. PMID 24552405.

- ^ a b c d e f Ludlow M, McQuaid S, Milner D, de Swart RL, Duprex WP (January 2015). "Pathological consequences of systemic measles virus infection". The Journal of Pathology. 235 (2): 253–65. doi:10.1002/path.4457. PMID 25294240.

- ^ a b Baxby D (1997). "Classic Paper: Henry Koplik. The diagnosis of the invasion of measles from a study of the exanthema as it appears on the buccal membrane". Reviews in Medical Virology. 7 (2): 71–74. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1654(199707)7:2<71::AID-RMV185>3.0.CO;2-S. PMID 10398471.

- ^ NHS UK: Symptoms of measles. Last reviewed: 26/01/2010 Archived 2011-01-31 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Gardiner, W. T. (2007). "Otitis Media in Measles". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 39 (11): 614–17. doi:10.1017/S0022215100026712.

- ^ Fisher DL, Defres S, Solomon T (2014). "Measles-induced encephalitis". QJM. 108 (3): 177–82. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcu113. PMID 24865261.

- ^ Anlar B (2013). "Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis and chronic viral encephalitis". Pediatric Neurology Part II. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 112. pp. 1183–89. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52910-7.00039-8. ISBN 9780444529107. PMID 23622327.

- ^ Semba RD, Bloem MW (March 2004). "Measles blindness". Survey of Ophthalmology. 49 (2): 243–55. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.12.005. PMID 14998696.

- ^ Gupta, Piyush; Menon, P. S. N.; Ramji, Siddarth; Lodha, Rakesh (2015). PG Textbook of Pediatrics: Volume 2: Infections and Systemic Disorders. JP Medical Ltd. p. 1158. ISBN 9789351529552.

- ^ Griffin, DE (July 2010). "Measles virus-induced suppression of immune responses". Immunological Reviews. 236: 176–89. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00925.x. PMC 2908915. PMID 20636817.

- ^ Rota, Paul A.; Moss, William J.; Takeda, Makoto; de Swart, Rik L.; Thompson, Kimberly M.; Goodson, James L. (14 July 2016). "Measles". Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2: 16049. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.49. PMID 27411684.

- ^ Ellison, J.B (1931). "Pneumonia in Measles". 1931 Archives of Disease in Childhood. 6 (31): 37–52. doi:10.1136/adc.6.31.37. PMC 1975146. PMID 21031836.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chen S.S.P. (October 3, 2011). Measles (Report). Medscape. Archived from the original on September 25, 2011.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Measles | For Healthcare Professionals". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements (2013). "Vitamin A". U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sabella C (2010). "Measles: Not just a childhood rash". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 77 (3): 207–13. doi:10.3949/ccjm.77a.09123. PMID 20200172.

- ^ a b Perry RT, Halsey NA (May 1, 2004). "The Clinical Significance of Measles: A Review". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 189 (S1): S4–16. doi:10.1086/377712. PMID 15106083.

- ^ Sension MG, Quinn TC, Markowitz LE, Linnan MJ, Jones TS, Francis HL, Nzilambi N, Duma MN, Ryder RW (1988). "Measles in hospitalized African children with human immunodeficiency virus". American Journal of Diseases of Children. 142 (12): 1271–72. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150120025021. PMID 3195521.

- ^ a b Cohen BE, Durstenfeld A, Roehm PC (July 2014). "Viral causes of hearing loss: a review for hearing health professionals". Trends in Hearing. 18: 2331216514541361. doi:10.1177/2331216514541361. PMC 4222184. PMID 25080364.

- ^ a b c d e "Measles". CDC. 2 April 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Gowda VK, Sukanya V (2012). "Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome with Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis". Pediatric Neurology. 47 (5): 379–81. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.06.020. PMID 23044024.

- ^ Waggoner JJ, Soda EA, Deresinski S (October 2013). "Rare and emerging viral infections in transplant recipients". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 57 (8): 1182–88. doi:10.1093/cid/cit456. PMID 23839998.

- ^ a b c d e Leuridan E, Sabbe M, Van Damme P (September 2012). "Measles outbreak in Europe: susceptibility of infants too young to be immunized". Vaccine. 30 (41): 5905–13. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.035. PMID 22841972.

- ^ a b c d e f Moss, WJ; Griffin, DE (14 January 2012). "Measles". Lancet. 379 (9811): 153–64. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62352-5. PMID 21855993.

- ^ a b Textbook of Microbiology & Immunology. Elsevier India. 2009. p. 535. ISBN 9788131221631.

- ^ Kaslow, Richard A.; Stanberry, Lawrence R.; Duc, James W. Le (2014). Viral Infections of Humans: Epidemiology and Control. Springer. p. 540. ISBN 9781489974488.

- ^ Schaechter's Mechanisms of Microbial Disease. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2012. p. 357. ISBN 9780781787444.

- ^ "Measles". www.cdc.gov. 2 April 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Durrheim DN, Kelly H, Ferson MJ, Featherstone D (August 2007). "Remaining measles challenges in Australia". The Medical Journal of Australia. 187 (3): 181–84. PMID 17680748. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Friedman M, Hadari I, Goldstein V, Sarov I (1983). "Virus-specific secretory IgA antibodies as a means of rapid diagnosis of measles and mumps infection". Israel Journal of Medical Sciences. 19 (10): 881–84. PMID 6662670.

- ^ Galindo BM, Concepción D, Galindo MA, Pérez A, Saiz J (2012). "Vaccine-related adverse events in Cuban children, 1999–2008". MEDICC Review. 14 (1): 38–43. PMID 22334111. Archived from the original on 2012-02-24.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Helfand RF, Witte D, Fowlkes A, Garcia P, Yang C, Fudzulani R, Walls L, Bae S, Strebel P, Broadhead R, Bellini WJ, Cutts F (2008). "Evaluation of the immune response to a 2-dose measles vaccination schedule administered at 6 and 9 months of age to HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children in Malawi". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 198 (10): 1457–65. doi:10.1086/592756. PMID 18828743.

- ^ Ołdakowska A, Marczyńska M (2008). "Measles vaccination in HIV-infected children". Medycyna Wieku Rozwojowego. 12 (2 Pt 2): 675–80. PMID 19418943.

- ^ UNICEF (2007). "Global goal to reduce measles deaths in children surpassed". Joint press release. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McLean HQ, Fiebelkorn AP, Temte JL, Wallace GS; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (14 June 2013). "Prevention of measles, rubella, congenital rubella syndrome, and mumps, 2013: summary recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 62 (RR-04): 1–34. PMID 23760231. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hyle EP, Rao SR, Jentes ES, Parker Fiebelkorn A, Hagmann SHF, Taylor Walker A, Walensky RP, Ryan ET, LaRocque RC (18 July 2017). "Missed Opportunities for Measles, Mumps, Rubella Vaccination Among Departing U.S. Adult Travelers Receiving Pretravel Health Consultations". Ann Intern Med. 167 (2): 77–84. doi:10.7326/M16-2249. PMC 5513758. PMID 28505632.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Measles vaccines: WHO position paper – April 2017" (PDF). Releve Epidemiologique Hebdomadaire. 92 (17): 205–27. 28 April 2017. PMID 28459148.

- ^ Casteels-Van Daele M, Van Geet C, Wouters C, Eggermont E (April 2000). "Reye syndrome revisited: a descriptive term covering a group of heterogeneous disorders". European Journal of Pediatrics. 159 (9): 641–48. doi:10.1007/PL00008399. PMID 11014461. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

Reye syndrome is a non-specific descriptive term covering a group of heterogeneous disorders. Moreover, not only the use of acetylsalicylic acid but also of antiemetics is statistically significant in Reye syndrome cases. Both facts weaken the validity of the epidemiological surveys suggesting a link with acetylsalicylic acid.

- ^ Schrör K (2007). "Aspirin and Reye Syndrome: A Review of the Evidence". Paediatric Drugs. 9 (3): 195–204. doi:10.2165/00148581-200709030-00008. PMID 17523700. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

The suggestion of a defined cause-effect relationship between aspirin intake and Reye syndrome in children is not supported by sufficient facts. Clearly, no drug treatment is without side effects. Thus, a balanced view of whether treatment with a certain drug is justified in terms of the benefit/risk ratio is always necessary. Aspirin is no exception.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Macdonald S (2002). "Aspirin use to be banned in under 16 year olds". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 325 (7371): 988c–988. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7371.988/c. PMC 1169585. PMID 12411346.

Professor Alasdair Breckenridge, said, "There are plenty of analgesic products containing paracetamol and ibuprofen for this age group not associated with Reye's syndrome. There is simply no need to expose those under 16 to the risk—however small."

- ^ "Aspirin and Reye's Syndrome". MHRA. October 2003. Archived from the original on 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (June 1982). "Surgeon General's advisory on the use of salicylates and Reye syndrome". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 31 (22): 289–90. PMID 6810083. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Reye's Syndrome at NINDS "Epidemiologic evidence indicates that aspirin (salicylate) is the major preventable risk factor for Reye's syndrome. The mechanism by which aspirin and other salicylates trigger Reye's syndrome is not completely understood."

- ^ "Measles vaccines: WHO position paper" (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 84 (35): 349–60. 28 August 2009. PMID 19714924. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about Measles". Washington State Department of Health. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

[Vitamin A] cannot prevent or cure the measles

- ^ Huiming Y, Chaomin W, Meng M (2005). Yang H (ed.). "Vitamin A for treating measles in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD001479. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001479.pub3. PMID 16235283.

- ^ Awotiwon, Ajibola A.; Oduwole, Olabisi; Sinha, Anju; Okwundu, Charles I. (2017). "Zinc supplementation for the treatment of measles in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD011177. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011177.pub3. hdl:10019.1/104308. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 28631310.

- ^ "Complications of Measles". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2018-07-02. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Noyce RS, Richardson CD (September 2012). "Nectin 4 is the epithelial cell receptor for measles virus". Trends in Microbiology. 20 (9): 429–39. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2012.05.006. PMID 22721863.

- ^ "NINDS Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis Information Page". Archived from the original on 2014-10-17. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) "NINDS Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis Information Page" - ^ 14-193b. at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- ^ Bartlett, M.S. (1957). "Measles periodicity and community size". J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A (120): 48–70.

- ^ a b Black FL (1966). "Measles endemicity in insular populations; critical community size and its evolutionary implications". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 11 (2): 207–11. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(66)90161-5. PMID 5965486.

- ^ a b "Region of the Americas is declared free of measles". PAHO. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, et al. (Dec 15, 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

- ^ "Measles Data and Statistics" (PDF). Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "Complications of measles". CDC. November 3, 2014. Archived from the original on January 3, 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Measles Archived 2015-02-03 at the Wayback Machine, World Health Organization Fact sheet N°286. Retrieved June 28, 2012. Updated February 2014

- ^ WHO: Global summary on measles Archived 2013-08-14 at the Wayback Machine, 2006

- ^ Measles Surveillance Data after WHO Archived 2015-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, last updated 2014-3-6

- ^ Measles reported cases by WHO in 2014 Archived 2015-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Số người chết và mắc bệnh theo quốc gia Archived 2015-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, last update 2014-4-7 by WHO

- ^ "Measles—United States, 2005". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 22, 2006. Archived from the original on 13 March 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Reported Measles Cases by WHO region 2014, 2015, as of 07 July 201 Archived 2015-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, WHO

- ^ UNICEF Joint Press Release Archived 2015-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ WHO Weekly Epidemiology Record, 4th December 2009 WHO.int Archived 2013-10-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sixty-third World Health Assembly Agenda provisional agenda item 11.15 Global eradication of measles" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sixty-third World Health Assembly notes from day four". Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Elizabeth Whitman (2015-03-13). "Who Is Stefan Lanka? Court Orders German Measles Denier To Pay 100,000 Euros". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Europe observes a 4-fold increase in measles cases in 2017 compared to previous year". www.euro.who.int. 19 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Measles spreads again in the Americas". MercoPress. 28 March 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ a b Papania MJ, Wallace GS, Rota PA, Icenogle JP, Fiebelkorn AP, Armstrong GL, Reef SE, Redd SB, Abernathy ES, Barskey AE, Hao L, McLean HQ, Rota JS, Bellini WJ, Seward JF (February 2014). "Elimination of endemic measles, rubella, and congenital rubella syndrome from the Western hemisphere: the US experience". JAMA Pediatr. 168 (2): 148–55. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4342. PMID 24311021. Archived from the original on 2015-03-11. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Multistate Measles Outbreak Associated with an International Youth Sporting Event – Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Texas, August–September 2007". Www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Gastañaduy PA, Budd J, Fisher N, Redd SB, Fletcher J, Miller J, McFadden DJ 3rd, Rota J, Rota PA, Hickman C, Fowler B, Tatham L, Wallace GS, de Fijter S, Parker Fiebelkorn A, DiOrio M (6 October 2016). "A Measles Outbreak in an Underimmunized Amish Community in Ohio". N Engl J Med. 375 (14): 1343–54. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602295. PMID 27705270.

- ^ "Year in Review: Measles Linked to Disneyland". Archived from the original on 2017-05-19. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Clemmons, Nakia. "Measles – United States, January 4 – April 2, 2015". cdc.gov.

- ^ "Measles kills first patient in 12 years". USA Today. 2 July 2015. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "First Measles Death in US Since 2003 Highlights the Unknown Vulnerables – Phenomena: Germination". 2015-07-02. Archived from the original on 2015-07-03. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Maine confirms its first case of measles in 20 years". CBC News. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ News, KATU. "Measles case confirmed in Portland, about 500 people possibly exposed". KATU. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "TABLE 1. Weekly cases* of selected infrequently reported notifiable diseases (". wonder.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2019-01-12.

- ^ a b Alltucker, Ken (February 11, 2019). "A quarter of all kindergartners in Washington county aren't immunized. Now there's a measles crisis". USA Today. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ Howard, Jacqueline (January 9, 2019). "New York tackles 'largest measles outbreak' in state's recent history as cases spike globally". CNN. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ^ Goldstein-Street, Jake (January 28, 2019). "Amid measles outbreak, legislation proposed to ban vaccine exemptions". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ "Washington state is averaging more than one measles case per day in 2019". NBC News. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Amid Measles Outbreak, Anti-Vaxx Parents Have Put Others' Babies At Risk". MSN. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Belluz, Julia (27 January 2019). "Washington declared a public health emergency over measles. Thank vaccine-refusing parents". Vox. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ kashmiragander (28 January 2019). ""Dangerous" anti-vaxx warning issued by Washington officials as cases in measles outbreak continue to rise". Newsweek. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Redação do G1 (26 July 2016). "Sarampo está eliminado do Brasil, segundo comitê internacional". G1. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ a b Template:Cite article

- ^ a b Saúde, Ministério da. "Ministério da Saúde atualiza casos de sarampo". portalms.saude.gov.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- ^ "Vietnam minister calls for calm in face of 8,500 measles cases, 114 fatalities". Thanhniennews.com. 2014-04-18. Archived from the original on 2014-04-18. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Bộ Y tế: "VN đã phản ứng rất nhanh đối với dịch sởi"". Archived from the original on 2014-05-31.

- ^ Eastern Mirror. "WHO doctors in Myanmar's Naga areas identify 'mystery disease'". www.easternmirrornagaland.com. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Myanmar (02): (SA) fatal, measles confirmed". www.promedmail.org (Archive Number: 20160806.4398118). International Society for Infectious Diseases. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Furuse, Yuki; Akira Suzuki; Hitoshi Oshitani (2010-03-04). "Origin of measles virus: divergence from rinderpest virus between the 11th and 12th centuries". Virology Journal. 7: 52. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-7-52. ISSN 1743-422X. PMC 2838858. PMID 20202190.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Cohen SG (February 2008). "Measles and immunomodulation". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 121 (2): 543–44. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.1152. PMID 18269930.

- ^ "Maurice R. Hilleman Dies; Created Vaccines Archived 2012-10-20 at the Wayback Machine". The Washington Post. April 13, 2005.

- ^ Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A–M. ABC-CLIO. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1. Archived from the original on 2013-11-13.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Torrey EF and Yolken RH. 2005. Their bugs are worse than their bite. Washington Post, April 3, p. B01. Archived 2009-10-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Migration and Disease. Digital History.

- ^ Fiji School of Medicine Archived 2015-04-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Measles hits rare Andaman tribe Archived 2011-08-23 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. May 16, 2006.

- ^ "Live attenuated measles vaccine". EPI Newsletter / C Expanded Program on Immunization in the Americas. 2 (1): 6. 1980. PMID 12314356.

- ^ Rima BK, Earle JA, Yeo RP, Herlihy L, Baczko K, ter Meulen V, Carabaña J, Caballero M, Celma ML, Fernandez-Muñoz R (1995). "Temporal and geographical distribution of measles virus genotypes". The Journal of General Virology. 76 (5): 1173–80. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-76-5-1173. PMID 7730801.

- ^ Offit PA (2007). Vaccinated: One Man's Quest to Defeat the World's Deadliest Diseases. Washington, DC: Smithsonian. ISBN 978-0-06-122796-7.

- ^ "Measles Prevention: Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP) Archived 2012-05-15 at the Wayback Machine". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- ^ Measles: Questions and Answers, Archived 2013-01-24 at the Wayback Machine Immunization Action Coalition Archived 2008-08-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Measles Frequently Asked Questions about Measles in U.S". www.cdc.gov. 28 August 2018.

- ^ Stefan Lanka [in German] (April 1995). "HIV; Reality or artefact?". Virusmyth.com. Archived from the original on 2015-03-26. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Das Masern-Virus 100.000 € Belohnung! WANTeD Der Durchmesser" (PDF) (in German). 2011-11-24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Germany court orders measles sceptic to pay 100,000 euros". BBC News. BBC News Online. 2015-03-12. Archived from the original on 2015-03-31. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Steven Novella (2015-03-13). "Yes, Dr. Lanka, Measles is Real". NeuroLogica Blog. Archived from the original on 2015-03-31. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Abramson, Brian (2018). Vaccine, vaccination, and immunization law. Bloomberg Law. pp. 10–30. ISBN 9781682675830.

- ^ Bakalar, Nicholas (2015-05-07). "Measles May Increase Susceptibility to Other Infections". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mina; et al. (8 May 2015). "Long-term measles-induced immunomodulation increases overall childhood infectious disease mortality". Science. 348 (6235): 694–99. doi:10.1126/science.aaa3662. PMC 4823017. PMID 25954009.

{{cite journal}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help);|archive-url=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ White LK, Yoon JJ, Lee JK, Sun A, Du Y, Fu H, Snyder JP, Plemper RK (2007). "Nonnucleoside Inhibitor of Measles Virus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Complex Activity". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 51 (7): 2293–303. doi:10.1128/AAC.00289-07. PMC 1913224. PMID 17470652.

- ^ Krumm SA, Yan D, Hovingh ES, Evers TJ, Enkirch T, Reddy GP, Sun A, Saindane MT, Arrendale RF, Painter G, Liotta DC, Natchus MG, von Messling V, Plemper RK (2014). "An Orally Available, Small-Molecule Polymerase Inhibitor Shows Efficacy Against a Lethal Morbillivirus Infection in a Large Animal Model". Science Translational Medicine. 6 (232): 232ra52. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3008517. PMC 4080709. PMID 24739760.

- ^ "The measles virus is highly infectious, but rarely deadly". NewScientist.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- Initiative for Vaccine Research (IVR): Measles, World Health Organization (WHO)

- Measles FAQ from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States

- Case of an adult male with measles (facial photo)

- Pictures of measles

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Paramyxoviridae