Nigeria

Federal Republic of Nigeria | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Unity and Faith, Peace and Progress" | |

| Anthem: "Arise, O Compatriots" | |

| Capital | Abuja 9°4′N 7°29′E / 9.067°N 7.483°E |

| Largest city | Lagos |

| Official languages | English |

| National languages | |

| Other languages[2] | Over 525 languages[1] including: |

| Ethnic groups (2018)[3] | |

| Demonym(s) | Nigerian |

| Government | Federal presidential republic |

| Muhammadu Buhari | |

| Yemi Osinbajo | |

| Ahmed Lawan | |

| Femi Gbajabiamila | |

| Tanko Muhammad | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Independence from United Kingdom | |

| 1 October 1960 | |

| 1 October 1963 | |

| 29 May 1999 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 923,769 km2 (356,669 sq mi) (32nd) |

• Water (%) | 1.4 |

| Population | |

• 2021 estimate | 211,400,708[4] (7th) |

• 2006 census | 140,431,691 |

• Density | 218/km2 (564.6/sq mi) (42nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2021 estimate |

• Total | $1.116 trillion[5] (25th) |

• Per capita | $5,280 (129th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2021 estimate |

• Total | $514.079 billion[5] (29th) |

• Per capita | $2,432 (137th) |

| Gini (2020) | medium |

| HDI (2019) | low (161st) |

| Currency | Naira (₦) (NGN) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (WAT) |

| Driving side | right[8] |

| Calling code | +234 |

| ISO 3166 code | NG |

| Internet TLD | .ng |

Nigeria (/naɪˈdʒiriə/ ⓘ), officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is the most populous country in Africa; geographically situated between the Sahel to the north, and the Gulf of Guinea to the south in the Atlantic Ocean; covering an area of 923,769 square kilometres (356,669 sq mi), with a population of over 211 million. Nigeria borders Niger in the north, Chad in the northeast, Cameroon in the east, and Benin in the west. Nigeria is a federal republic comprising 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory, where the capital, Abuja, is located. The largest city in Nigeria is Lagos, one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world and the second-largest in Africa.

Nigeria has been home to several indigenous pre-colonial states and kingdoms since the second millennium BC, with the Nok civilization in the 15th century BC marking the first internal unification in the country. The modern state originated with British colonialization in the 19th century, taking its present territorial shape with the merging of the Southern Nigeria Protectorate and Northern Nigeria Protectorate in 1914 by Lord Lugard. The British set up administrative and legal structures while practising indirect rule through traditional chiefdoms in the Nigeria region.[9] Nigeria became a formally independent federation on October 1, 1960. It experienced a civil war from 1967 to 1970, followed by a succession of democratically elected civilian governments and military dictatorships, until achieving a stable democracy in the 1999 presidential election; the 2015 election was the first time an incumbent president had lost re-election.[10]

Nigeria is a multinational state inhabited by more than 250 ethnic groups speaking 500 distinct languages, all identifying with a wide variety of cultures.[11][12][13] The three largest ethnic groups are the Hausa in the north, Yoruba in the west, and Igbo in the east, together comprising over 60% of the total population.[14] The official language is English, chosen to facilitate linguistic unity at the national level.[15] Nigeria's constitution ensures freedom of religion[16] and it is home to some of the world's largest Muslim and Christian populations, simultaneously.[17] Nigeria is divided roughly in half between Muslims, who live mostly in the north, and Christians, who live mostly in the south; indigenous religions, such as those native to the Igbo and Yoruba ethnicities, are in the minority.[18]

Nigeria is a regional power in Africa, a middle power in international affairs, and is an emerging global power. Nigeria's economy is the largest in Africa, the 25th-largest in the world by nominal GDP, and 25th-largest by PPP. Nigeria is often referred to as the Giant of Africa owing to its large population and economy[19] and is considered to be an emerging market by the World Bank. However, the country ranks very low in the Human Development Index and remains one of the most corrupt nations in the world.[20][21] Nigeria is a founding member of the African Union and a member of many international organizations, including the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, NAM,[22] the Economic Community of West African States, and OPEC. It is also a member of the informal MINT group of countries and is one of the Next Eleven economies.

Etymology

The name Nigeria was taken from the Niger River running through the country. This name was coined on January 8, 1897, by British journalist Flora Shaw, who later married Lord Lugard, a British colonial administrator. The neighbouring Niger takes its name from the same river. The origin of the name Niger, which originally applied to only the middle reaches of the Niger River, is uncertain. The word is likely an alteration of the Tuareg name egerew n-igerewen used by inhabitants along the middle reaches of the river around Timbuktu before 19th-century European colonialism.[23][24]

History

Prehistory

Kainji Dam excavations revealed ironworking by the 2nd century BC. The transition from Neolithic times to the Iron Age was achieved without intermediate bronze production. Others suggest the technology moved west from the Nile Valley, although the Iron Age in the Niger Rivervalley and the forest region appears to predate the introduction of metallurgy in the upper savanna by more than 800 years.

The Nok civilization of Nigeria flourished between 1,500 BC and AD 200. It produced life-sized terracotta figures that are some of the earliest known sculptures in Sub-Saharan Africa[25][26][27][28][29] and smelted iron by about 550 BC and possibly a few centuries earlier.[30][31][32] Evidence of iron smelting has also been excavated at sites in the Nsukka region of southeast Nigeria: dating to 2000 BC at the site of Lejja[33] and to 750 BC and at the site of Opi.

Early history

The Kano Chronicle highlights an ancient history dating to around 999 AD of the Hausa Sahelian city-state of Kano, with other major Hausa cities (or Hausa Bakwai) of Daura, Hadeija, Kano, Katsina, Zazzau, Rano, and Gobir all having recorded histories dating back to the 10th century. With the spread of Islam from the 7th century AD, the area became known as Sudan or as Bilad Al Sudan (English: Land of the Blacks; Arabic: بلاد السودان). Since the populations were partially affiliated with the Arab Muslim culture of North Africa, they began Trans-Saharan trade and were referred to by the Arabic speakers as Al-Sudan (meaning "The Blacks") as they were considered an extended part of the Muslim world. There are early historical references by medieval Arab and Muslim historians and geographers which refer to the Kanem-Bornu Empire as the region's major centre for Islamic civilization.

The Kingdom of Nri of the Igbo people consolidated in the 10th century and continued until it lost its sovereignty to the British in 1911.[34][35] Nri was ruled by the Eze Nri, and the city of Nri is considered to be the foundation of Igbo culture. Nri and Aguleri, where the Igbo creation myth originates, are in the territory of the Umeuri clan. Members of the clan trace their lineages back to the patriarchal king-figure Eri.[36] In West Africa, the oldest bronzes made using the lost wax process were from Igbo-Ukwu, a city under Nri influence.[34] The Yoruba kingdoms of Ife and Oyo in southwestern Nigeria became prominent in the 12th[37][38] and 14th[39] centuries, respectively. The oldest signs of human settlement at Ife's current site date back to the 9th century,[37] and its material culture includes terracotta and bronze figures.

Pre-colonial era

In the 16th century, Portuguese explorers were the first Europeans to begin significant, direct trade with peoples of southern Nigeria, at the port they named Lagos (formerly Eko) and in Calabar along the region Slave Coast. Europeans traded goods with peoples at the coast; coastal trade with Europeans also marked the beginnings of the Atlantic slave trade.[40] The port of Calabar on the historical Bight of Biafra (now commonly referred to as the Bight of Bonny) became one of the largest slave-trading posts in West Africa in the era of the transatlantic slave trade. Other major slaving ports in Nigeria were located in Badagry, Lagos on the Bight of Benin and Bonny Island on the Bight of Biafra.[40][41] The majority of those enslaved and taken to these ports were captured in raids and wars.[42] Usually, the captives were taken back to the conquerors' territory as forced labour; after time, they were sometimes acculturated and absorbed into the conquerors' society. Slave routes were established throughout Nigeria linking the hinterland areas with the major coastal ports. Some of the more prolific slave-trading kingdoms who participated in the transatlantic slave trade were linked with the Edo's Benin Empire in the south, Oyo Empire in the southwest, and the Aro Confederacy in the southeast.[40][41] Benin's power lasted between the 15th and 19th centuries.[43] Oyo, at its territorial zenith in the late 17th to early 18th centuries, extended its influence from western Nigeria to modern-day Togo.

In the north, the incessant fighting amongst the Hausa city-states and the decline of the Bornu Empire gave rise to the Fulani people gaining headway into the region. Until this point, the Fulani a nomadic ethnic group primarily traversed the semi-desert Sahelian region, north of Sudan, with cattle and avoided trade and intermingling with the Sudanic peoples. At the beginning of the 19th century, Usman dan Fodio led a successful jihad against the Hausa Kingdoms founding the centralised Sokoto Caliphate. The empire with Arabic as its official language grew rapidly under his rule and that of his descendants, who sent out invading armies in every direction. The vast landlocked empire connected the east with the western Sudan region and made inroads down south conquering parts of the Oyo Empire (modern-day Kwara), and advanced towards the Yoruba heartland of Ibadan, to reach the Atlantic Ocean. The territory controlled by the empire included much of modern-day northern and central Nigeria. The sultan sent out emirs to establish a suzerainty over the conquered territories and promote Islamic civilization, the emirs in turn became increasingly rich and powerful through trade and slavery. By the 1890s, the largest slave population in the world, about two million, was concentrated in the territories of the Sokoto Caliphate. The use of slave labour was extensive, especially in agriculture.[44] By the time of its break-up in 1903 into various European colonies, the Sokoto Caliphate was one of the largest pre-colonial African states.[45]

British colonization

A changing legal imperative (the transatlantic slave trade was outlawed by Britain in 1807) and economic imperative (a desire for political and social stability) led most European powers to support the widespread cultivation of agricultural products, such as the palm, for use in European industry. The Atlantic slave trade was engaged in by European companies until it was outlawed in 1807. After that illegal smugglers purchased slaves along the coast by native slavers. Britain's West Africa Squadron sought to intercept the smugglers at sea. The rescued slaves were taken to Freetown, a colony in West Africa originally established by Lieutenant John Clarkson for the resettlement of slaves freed by Britain in North America after the American Revolutionary War.

Britain intervened in the Lagos kingship power struggle by bombarding Lagos in 1851, deposing the slave-trade-friendly Oba Kosoko, helping to install the amenable Oba Akitoye and signing the Treaty between Great Britain and Lagos on 1 January 1852. Britain annexed Lagos as a crown colony in August 1861 with the Lagos Treaty of Cession. British missionaries expanded their operations and travelled further inland. In 1864, Samuel Ajayi Crowther became the first African bishop of the Anglican Church.[46]

In 1885, British claims to a West African sphere of influence received recognition from other European nations at the Berlin Conference. The following year, it chartered the Royal Niger Company under the leadership of Sir George Taubman Goldie. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the company had vastly succeeded in subjugating the independent southern kingdoms along the Niger River, the British conquered Benin in 1897, and, in the Anglo-Aro War (1901–1902), defeated other opponents. The defeat of these states opened up the Niger area to British rule. In 1900, the company's territory came under the direct control of the British government and established the Southern Nigeria Protectorate as a British protectorate and part of the British Empire, the foremost world power at the time.

By 1902, the British had begun plans to move north into the Sokoto Caliphate. British General Lord Frederick Lugard was tasked by the Colonial Office to implement the agenda. Lugard used rivalries between many of the emirs in the southern reach of the caliphate and the central Sokoto administration to prevent any defence as he worked towards the capital. As the British approached the city of Sokoto, Sultan Muhammadu Attahiru I organized a quick defence of the city and fought the advancing British-led forces. The British force quickly won, sending Attahiru I and thousands of followers on a Mahdist hijra. In the northeast, the decline of the Bornu Empire gave rise to the British-controlled Borno Emirate which established Abubakar Garbai of Borno as ruler.

In 1903, the British victory in the Battle of Kano gave them a logistical edge in pacifying the heartland of the Sokoto Caliphate and parts of the former Bornu Empire. On 13 March 1903, at the grand market square of Sokoto, the last vizier of the caliphate officially conceded to British rule. The British appointed Muhammadu Attahiru II as the new caliph. Lugard abolished the caliphate but retained the title sultan as a symbolic position in the newly organized Northern Nigeria Protectorate. This remnant became known as "Sokoto Sultanate Council". In June 1903, the British defeated the remaining forces of Attahiru I and killed him; by 1906 resistance to British rule had ended.

On 1 January 1914, the British formally united the Southern Nigeria Protectorate and the Northern Nigeria Protectorate into the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria. Administratively, Nigeria remained divided into the Northern and Southern Protectorates and Lagos Colony. Inhabitants of the southern region sustained more interaction, economic and cultural, with the British and other Europeans owing to the coastal economy.[47] Following World War II, in response to the growth of Nigerian nationalism and demands for independence, successive constitutions legislated by the British government moved Nigeria toward self-government on a representative and increasingly federal basis. By the middle of the 20th century, a great wave for independence was sweeping across Africa.

Christian missions established Western educational institutions in the protectorates. Under Britain's policy of indirect rule and validation of Islamic tradition, the Crown did not encourage the operation of Christian missions in the northern, Islamic part of the country.[48] Some children of the southern elite went to Great Britain to pursue higher education. By independence in 1960, regional differences in modern educational access were marked. The legacy, though less pronounced, continues to the present day. Imbalances between north and south were expressed in Nigeria's political life as well. For instance, northern Nigeria did not outlaw slavery until 1936 whilst in other parts of Nigeria slavery was abolished soon after colonialism.[49][41]

Nigeria gained a degree of self-rule in 1954, and full independence from the United Kingdom on October 1, 1960, as the Federation of Nigeria with Abubakar Tafawa Balewa as its prime minister, while retaining the British monarch, Elizabeth II, as nominal head of state and Queen of Nigeria. Azikiwe replaced the colonial governor-general in November 1960. At independence, the cultural and political differences were sharp among Nigeria's dominant ethnic groups: the Hausa in the north, Igbo in the east and Yoruba in the west.[50]

The founding government was a coalition of conservative parties: the Northern People's Congress led by Sir Ahmadu Bello, a party dominated by Muslim northerners, and the Igbo and Christian-dominated National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons led by Nnamdi Azikiwe. The opposition comprised the comparatively liberal Action Group, which was largely dominated by the Yoruba and led by Obafemi Awolowo. An imbalance was created in the polity as the result of the 1961 plebiscite. Southern Cameroons opted to join the Republic of Cameroon while Northern Cameroons chose to join Nigeria. The northern part of the country became larger than the southern part.

Republican era

Fall of the First Republic and Civil War

In 1963, the nation established a federal republic, with Azikiwe as its first president. The disequilibrium and perceived corruption of the electoral and political process led to two military coups in 1966. The first coup was in January 1966 and was led mostly by Igbo soldiers under Majors Emmanuel Ifeajuna and Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu. The coup plotters succeeded in assassinating Sir Ahmadu Bello and Abubakar Tafawa Balewa alongside prominent leaders of the Northern Region and also Premier Samuel Akintola of the Western Region, but the coup plotters struggled to form a central government. Senate President Nwafor Orizu handed over government control to the Army, under the command of another Igbo officer, General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi. Later, the counter-coup of 1966, supported primarily by Northern military officers, facilitated the rise of Yakubu Gowon as military head of state. Tension rose between north and south; Igbos in northern cities suffered persecution and many fled to the Eastern Region.[51]

In May 1967, Governor of the Eastern Region Lt. Colonel Emeka Ojukwu declared the region independent from the federation as a state called the Republic of Biafra, under his leadership.[52][53] This declaration precipitated the Nigerian Civil War, which began as the official Nigerian government side attacked Biafra on 6 July 1967, at Garkem. The 30-month war, with a long siege of Biafra and its isolation from trade and supplies, ended in January 1970.[54] Estimates of the number of dead in the former Eastern Region during the 30-month civil war range from one to three million.[55] France, Egypt, the Soviet Union, Britain, Israel, and others were deeply involved in the civil war behind the scenes. Britain and the Soviet Union were the main military backers of the Nigerian government, with Nigeria utilizing air support from Egyptian pilots provided by Gamal Abdel Nasser,[56][57] while France and Israel aided the Biafrans. The Congolese government, under President Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, took an early stand on the Biafran secession, voicing strong support for the Nigerian federal government[58] and deploying thousands of troops to fight against the secessionists.[59][60]

Following the war, Nigeria enjoyed an oil boom in the 1970s, during which the country joined OPEC and received huge oil revenues. Despite these revenues, the military government did little to improve the standard of living of the population, help small and medium businesses, or invest in infrastructure. As oil revenues fueled the rise of federal subsidies to states, the federal government became the centre of political struggle and the threshold of power in the country. As oil production and revenue rose, the Nigerian government became increasingly dependent on oil revenues and international commodity markets for budgetary and economic concerns.[61] The coup in July 1975, led by Generals Shehu Musa Yar'Adua and Joseph Garba, ousted Gowon,[62] who fled to Britain.[63] The coup plotters wanted to replace Gowon's autocratic rule with a triumvirate of three brigadier generals whose decisions could be vetoed by a Supreme Military Council. For this triumvirate, they convinced General Murtala Muhammed to become military head of state, with General Olusegun Obasanjo as his second-in-command, and General Theophilus Danjuma as the third.[64] Together, the triumvirate introduced austerity measures to stem inflation, established a Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau, replaced all military governors with new officers, and launched "Operation Deadwood" through which they fired 11,000 officials from the civil service.[65]

Colonel Buka Suka Dimka launched a February 1976 coup attempt, during which General Murtala Muhammed was assassinated. Dimka lacked widespread support among the military, and his coup failed, forcing him to flee.[66] After the coup attempt, General Olusegun Obasanjo was appointed military head of state.[67] As head of state, Obasanjo vowed to continue Murtala's policies.[68] Aware of the danger of alienating northern Nigerians, Obasanjo brought General Shehu Yar'Adua as his replacement and second-in-command as Chief of Staff, Supreme Headquarters completing the military triumvirate, with Obasanjo as head of state and General Theophilus Danjuma as Chief of Army Staff, the three went on to re-establish control over the military regime and organized the military's transfer of power programme: states creation and national delimitation, local government reforms and the constitutional drafting committee for a new republic.[69]

Second Republic (1979–1983)

In 1977, a constituent assembly was elected to draft a new constitution, which was published on September 21, 1978, when the ban on political activity was lifted. The military carefully planned the return to civilian rule putting in place measures to ensure that political parties had broader support than witnessed during the first republic. In 1979, five political parties competed in a series of elections in which Alhaji Shehu Shagari of the National Party of Nigeria (NPN) was elected president. All five parties won representation in the National Assembly. On October 1, 1979, Shehu Shagari was sworn in as the first President and Commander-in-Chief of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. Obasanjo peacefully transferred power to Shagari, becoming the first head of state in Nigerian history to willingly step down.

The Shagari government became viewed as corrupt by virtually all sectors of Nigerian society. In 1983, the inspectors of the state-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation began to notice "the slow poisoning of the waters of this country".[70][71] In August 1983 Shagari and the NPN were returned to power in a landslide victory, with a majority of seats in the National Assembly and control of 12 state governments. But the elections were marred by violence, and allegations of widespread vote-rigging and electoral malfeasance led to legal battles over the results. There were also uncertainties, such as in the first republic, that political leaders may be unable to govern properly.

Military and Third Republic (1983–1999)

The 1983 military coup d'état took place on New Year's Eve of that year. It was coordinated by key officers of the Nigerian military and led to the overthrow of the government and the installation of Major General Muhammadu Buhari as head of state. The military coup of Muhammadu Buhari shortly after the regime's re-election in 1984 was generally viewed as a positive development.[72] Buhari promised major reforms, but his government fared little better than its predecessor. General Buhari was overthrown in a 1985 military coup d'état led by General Ibrahim Babangida, who established the Armed Forces Ruling Council and became military president and commander in chief of the armed forces.[73] In 1986, he established the Nigerian Political Bureau which made recommendations for the transition to the Third Nigerian Republic. In 1989, Babangida started making plans for the transition to the Third Nigerian Republic. Babangida survived the 1990 Nigerian coup d'état attempt, then postponed a promised return to democracy to 1992.[74]

He legalized the formation of political parties and formed the two-party system with the Social Democratic Party and National Republican Convention ahead of the 1992 general elections. He urged all Nigerians to join either of the parties, which Chief Bola Ige referred to as "two leper hands." The two-party state had been a Political Bureau recommendation. After a census was conducted, the National Electoral Commission announced on 24 January 1992, that both legislative elections to a bicameral National Assembly and a presidential election would be held later that year. The adopted process advocated that any candidate needed to pass through adoption for all elective positions from the local government, state government and federal government.[75]

The 1993 presidential election held on 12 June, was the first since the military coup of 1983. The results, though not officially declared by the National Electoral Commission, showed the duo of Moshood Abiola and Baba Gana Kingibe of the Social Democratic Party defeated Bashir Tofa and Sylvester Ugoh of the National Republican Convention by over 2.3 million votes. However, Babangida annulled the elections, leading to massive civilian protests that effectively shut down the country for weeks. In August 1993, Babangida finally kept his promise to relinquish power to a civilian government but not before appointing Ernest Shonekan head of the interim national government.[76] Babangida's regime has been considered the most corrupt and responsible for creating a culture of corruption in Nigeria.[77] Shonekan's interim government, the shortest in the political history of the country, was overthrown in a coup d'état of 1993 led by General Sani Abacha, who used military force on a wide scale to suppress the continuing civilian unrest.

In 1995, the government hanged environmentalist Ken Saro-Wiwa on trumped-up charges in the deaths of four Ogoni elders. Lawsuits under the American Alien Tort Statute against Royal Dutch Shell and Brian Anderson, the head of Shell's Nigerian operation, settled out of court with Shell continuing to deny liability.[78] Several hundred million dollars in accounts traced to Abacha were discovered in 1999.[79] The regime came to an end in 1998 when the dictator died in the villa. He looted money to offshore accounts in western European banks and defeated coup plots by arresting and bribing generals and politicians. His successor, General Abdulsalami Abubakar, adopted a new constitution on May 5, 1999, which provided for multiparty elections.

Fourth Republic (1999–present)

On May 29, 1999, Abubakar transferred power to the winner of the 1999 presidential election, former military ruler General Olusegun Obasanjo as the second democratically elected civilian President of Nigeria heralding the beginning of the Fourth Nigerian Republic.[80] This ended almost 33 years of military rule from 1966 until 1999, excluding the short-lived second republic (between 1979 and 1983) by military dictators who seized power in coups d'état and counter-coups.

Although the elections that brought Obasanjo to power and for a second term in the 2003 presidential election were condemned as unfree and unfair, Nigeria has shown marked improvements in attempts to tackle government corruption and hasten development.[81] Ethnic violence for control over the oil-producing Niger Delta region and an insurgency in the northeast are some of the issues facing the country. Umaru Yar'Adua of the People's Democratic Party came into power in the general election of 2007. The international community, which had been observing Nigerian elections to encourage a free and fair process, condemned this one as being severely flawed.[82] President Olusegun Obasanjo acknowledged fraud and other electoral "lapses" but said the result reflected opinion polls. In a national television address in 2007, he added that if Nigerians did not like the victory of his handpicked successor, they would have an opportunity to vote again in four years.[83] Yar'Adua died on May 5, 2010. Goodluck Jonathan was sworn in as Yar'Adua's successor,[84] becoming the 14th head of state.[85][86] Jonathan went on to win the 2011 presidential election, with the international media reporting the elections as having run smoothly with relatively little violence or voter fraud, in contrast to previous elections.[87]

Ahead of the general election of 2015, a merger of the biggest opposition parties – the Action Congress of Nigeria, the Congress for Progressive Change, the All Nigeria Peoples Party (a faction of the All Progressives Grand Alliance), and the new PDP (a faction of serving governors of the ruling People's Democratic Party) – formed the All Progressives Congress. In the 2015 presidential election, former military head of state General Muhammadu Buhari – who had previously contested in the 2003, 2007, and 2011 presidential elections—defeated incumbent Jonathan of the People's Democratic Party by over two million votes, ending the party's sixteen-year rule in the country and marking the first time in the history of Nigeria that an incumbent president lost to an opposition candidate. Observers generally praised the election as being fair. Jonathan was generally praised for conceding defeat and limiting the risk of unrest.[88][89][90][91] In the 2019 presidential election, Buhari was re-elected for a second term in office defeating his closet rival Atiku Abubakar.[92]

Politics

Nigeria is a federal republic modelled after the United States,[93] with executive power exercised by the President. The president is both head of state and head of the federal government; the president is elected by popular vote to a maximum of two four-year terms.[94] The president's power is checked by a Senate and a House of Representatives, which are combined in a bicameral body called the National Assembly. The Senate is a 109-seat body with three members from each state and one from the capital region of Abuja; members are elected by popular vote to four-year terms. The House contains 360 seats, with the number of seats per state determined by population.[94] Template:Nigerian symbols Ethnocentrism, tribalism, religious persecution, and prebendalism have plagued Nigerian politics both before and after independence in 1960. All major parties have practised vote-rigging and other means of coercion to remain competitive. In the period before 1983 election, a report prepared by the National Institute of Policy and Strategic Studies showed that only the 1959 and 1979 elections were held without systemic rigging.[95] In 2012, Nigeria was estimated to have lost over $400 billion to corruption since independence.[96] Kin-selective altruism is prevalent in Nigerian politics, resulting in tribalist efforts to concentrate Federal power to a particular region of their interests.[97] Because of the above issues, Nigeria's political parties are pan-national and secular in character (though this does not preclude the continuing preeminence of the dominant ethnicities).[98][99] The two major political parties are the People's Democratic Party of Nigeria and the All Progressives Congress, with twenty registered minor opposition parties.

Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba and Igbo are the three largest ethnic groups in Nigeria and have maintained historical preeminence in Nigerian politics; competition amongst these three groups has fueled animosity.[98] Following the bloody civil war, nationalism has seen an increase in the southern part of the country leading to active secessionist movements such as the Oodua Peoples Congress and the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra, though these groups are generally small and not representative of the entire ethnic group.

Law

The country has a judicial branch, with the highest court being the Supreme Court of Nigeria.[94] There are three distinct systems of law in Nigeria:

- Common law, derived from its British colonial past, and development of its own after independence;

- Customary law, derived from indigenous traditional norms and practice, including the dispute resolution meetings of pre-colonial Yorubaland secret societies such as the Oyo Mesi and Ogboni, as well as the Ekpe and Okonko of Igboland and Ibibioland;

- Sharia law, used only in the predominantly Muslim northern states of the country. It is an Islamic legal system that had been used long before the colonial administration.

It is also very important to know that the laws of Nigeria are written down in a book. This means that Nigeria practices written constitution. The current written constitution of Nigeria is the 1999 constitution as amended.[100]

Military

The Nigerian military is charged with protecting the Federal Republic of Nigeria, promoting Nigeria's global security interests, and supporting peacekeeping efforts, especially in West Africa. This is in support of the doctrine sometimes called Pax Nigeriana. The Nigerian Military consists of an army, a navy, and an air force.[94] The military in Nigeria has played a major role in the country's history since independence. Various juntas have seized control of the country and ruled it through most of its history. Its last period of military rule ended in 1999 following the sudden death of Sani Abacha in 1998. His successor, Abdulsalam Abubakar, handed over power to the democratically elected government of Olusegun Obasanjo the next year.

As Africa's most populated country, Nigeria has repositioned its military as a peacekeeping force on the continent. Since 1995, the Nigerian military, through ECOMOG mandates, has been deployed as peacekeepers in Liberia (1997), Ivory Coast (1997–1999), and Sierra Leone (1997–1999).[101] Under an African Union mandate, it has stationed forces in Sudan's Darfur region to try to establish peace. The Nigerian military has been deployed across West Africa, curbing terrorism in countries like Mali, Senegal, Chad, and Cameroon, as well as dealing with the Mali War, and getting Yahya Jammeh out of power in 2017.[citation needed]

Foreign relations

Upon gaining independence in 1960, Nigeria made African unity the centrepiece of its foreign policy and played a leading role in the fight against the apartheid government in South Africa.[102] One exception to the African focus was Nigeria's close relationship developed with Israel throughout the 1960s. Israel sponsored and oversaw the construction of Nigeria's parliament buildings.[103]

Nigeria's foreign policy was put to the test in the 1970s after the country emerged united from its civil war. It supported movements against white minority governments in the Southern Africa sub-region. Nigeria backed the African National Congress by taking a committed tough line about the South African government and their military actions in southern Africa. Nigeria was a founding member of the Organisation for African Unity (now the African Union) and has tremendous influence in West Africa and Africa on the whole. Nigeria founded regional cooperative efforts in West Africa, functioning as the standard-bearer for the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and ECOMOG (especially during the Liberia and Sierra Leone civil wars) - which are economic and military organizations, respectively.

With this Africa-centered stance, Nigeria readily sent troops to the Congo at the behest of the United Nations shortly after independence (and has maintained membership since that time). Nigeria also supported several Pan-African and pro-self government causes in the 1970s, including garnering support for Angola's MPLA, SWAPO in Namibia, and aiding opposition to the minority governments of Portuguese Mozambique, and Rhodesia. Nigeria retains membership in the Non-Aligned Movement. In late November 2006, it organised an Africa-South America Summit in Abuja to promote what some attendees termed "South-South" linkages on a variety of fronts.[104] Nigeria is also a member of the International Criminal Court and the Commonwealth of Nations. It was temporarily expelled from the latter in 1995 when ruled by the Abacha regime.

Nigeria has remained a key player in the international oil industry since the 1970s and maintains membership in OPEC, which it joined in July 1971. Its status as a major petroleum producer figures prominently in its sometimes volatile international relations with developed countries, notably the United States, and with developing countries.[105]

Since 2000, China-Nigerian trade relations have risen exponentially. There has been an increase in total trade of over 10,384 million dollars between the two nations from 2000 to 2016.[106] However, the structure of the China-Nigerian trade relationship has become a major political issue for the Nigerian state. This is illustrated by the fact that Chinese exports account for around 80 per cent of total bilateral trade volumes.[107] This has resulted in a serious trade imbalance, with Nigeria importing ten times more than it exports to China.[108] Subsequently, Nigeria's economy is becoming over-reliant on cheap imports to sustain itself, resulting in a clear decline in Nigerian Industry under such arrangements.[109]

Continuing its Africa-centered foreign policy, Nigeria introduced the Idea of a single currency for West Africa known as the Eco under the presumption that it would be led by the naira, but on December 21, 2019; Ivorian President Alassane Ouattara along with Emmanuel Macron and multiple other UEMOA States, announced that they would merely rename the CFA franc instead of replacing the currency as originally intended. As of 2020, the Eco currency has been delayed to 2025.[110]

Administrative divisions

Nigeria is divided into thirty-six states and one Federal Capital Territory, which are further sub-divided into 774 local government areas. In some contexts, the states are aggregated into six geopolitical zones: North West, North East, North Central, South West, South East, and South-South.[111][112]

Nigeria has five cities with a population of over a million (from largest to smallest): Lagos, Kano, Ibadan, Benin City and Port Harcourt. Lagos is the largest city in Africa, with a population of over 12 million in its urban area.[113]

Geography

Nigeria is located in western Africa on the Gulf of Guinea and has a total area of 923,768 km2 (356,669 sq mi),[114] making it the world's 32nd-largest country. Its borders span 4,047 kilometres (2,515 mi), and it shares borders with Benin (773 km or 480 mi), Niger (1,497 km or 930 mi), Chad (87 km or 54 mi), and Cameroon (including the separatist Ambazonia) 1,690 km or 1,050 mi. Its coastline is at least 853 km (530 mi).[115] Nigeria lies between latitudes 4° and 14°N, and longitudes 2° and 15°E. The highest point in Nigeria is Chappal Waddi at 2,419 m (7,936 ft). The main rivers are the Niger and the Benue, which converge and empty into the Niger Delta. This is one of the world's largest river deltas and the location of a large area of Central African mangroves.

Nigeria's most expansive topographical region is that of the valleys of the Niger and Benue river valleys (which merge and form a Y-shape).[116] To the southwest of the Niger is a "rugged" highland. To the southeast of the Benue are hills and mountains, which form the Mambilla Plateau, the highest plateau in Nigeria. This plateau extends through the border with Cameroon, where the montane land is part of the Bamenda Highlands of Cameroon.

Climate

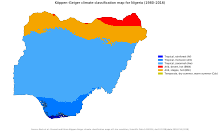

Nigeria has a varied landscape. The far south is defined by its tropical rainforest climate, where annual rainfall is 1,500 to 2,000 millimetres (60 to 80 in) per year.[117] In the southeast stands the Obudu Plateau. Coastal plains are found in both the southwest and the southeast.[116] Mangrove swamps are found along the coast.[118]

The area near the border with Cameroon close to the coast is rich rainforest and part of the Cross-Sanaga-Bioko coastal forests ecoregion, an important centre for biodiversity. It is a habitat for the drill primate, which is found in the wild only in this area and across the border in Cameroon. The areas surrounding Calabar, Cross River State, also in this forest, are believed to contain the world's largest diversity of butterflies. The area of southern Nigeria between the Niger and the Cross Rivers has lost most of its forest because of development and harvesting by increased population, with it being replaced by grassland.

Everything in between the far south and the far north is savannah (insignificant tree cover, with grasses and flowers located between trees). Rainfall is more limited to between 500 and 1,500 millimetres (20 and 60 in) per year.[117] The savannah zone's three categories are Guinean forest-savanna mosaic, Sudan savannah, and Sahel savannah. Guinean forest-savanna mosaic is plains of tall grass interrupted by trees. Sudan savannah is similar but with shorter grasses and shorter trees. Sahel savannah consists of patches of grass and sand, found in the northeast.[118] In the Sahel region, rain is less than 500 millimetres (20 in) per year, and the Sahara Desert is encroaching.[117] In the dry northeast corner of the country lies Lake Chad, which Nigeria shares with Niger, Chad and Cameroon.

Plant ecology

Nigeria has numerous tree species, of which the majority of them are native while few are exotic. A high percentage of man-made forests in the country is dominated by exotic species.[119] This culminated from the assumption that exotic trees are fast-growing. However, studies have also investigated the growth of indigenous trees in with that of exotic species. Due to overexploitation, the remaining natural ecosystems and primary forests in Nigeria are restricted to the protected areas which include one biosphere reserve, seven national parks, one World Heritage site, 12 Strict Nature Reserves (SNRs), 32 game reserves/wildlife sanctuaries, and hundreds of forest reserves. These are in addition to several ex-situ conservation sites such as arboreta, botanical gardens, zoological gardens, and gene banks managed by several tertiary and research institutions[120]

Many countries in Africa are affected by Invasive Alien Species (IAS). In 2004, the IUCN–World Conservation Union identified 81 IAS in South Africa, 49 in Mauritius, 37 in Algeria and Madagascar, 35 in Kenya, 28 in Egypt, 26 in Ghana and Zimbabwe, and 22 in Ethiopia.[121] However, very little is known about IAS in Nigeria, with most technical reports and literature reporting fewer than 10 invasive plants in the country. Aside from plant invaders, Rattus rattus and Avian influenza virus were also considered IAS in Nigeria.[122] The initial entry of IAS into Nigeria was mainly through exotic plant introductions by the colonial rulers either for forest tree plantations or for ornamental purposes. The entry of exotic plants into Nigeria during the post-independence era was encouraged by increasing economic activity, the commencement of commercial oil explorations, the introduction through ships, and the introduction of ornamental plants by commercial floriculturists.[122]

In the semi-arid and dry sub-humid savannas of West Africa, including Nigeria, numerous species of herbaceous dicots especially from the genera Crotalaria, Alysicarpus, Cassia and Ipomea are known to be widely used in livestock production. Quite often they are plucked or cut and fed either as fresh or conserved fodders. The utilization of these and many other herbs growing naturally within the farm environment is opportunistic.[120]

Many other species native to Nigeria, including soybean and its varieties, serve as an important source of oil and protein in this region.[citation needed] There are also many plants with medicinal purposes that are used to aid the therapy in many organs. Some of these vegetations include Euphorbiaceae, which serve the purpose of aiding malaria, gastrointestinal disorders respectively and many other infections. Different stress factors such as droughts, low soil nutrients and susceptibility to pests have contributed to Maize plantations being an integral part of agriculture in this region.[123]

As industrialization has increased, it has also put species of trees in the forest at risk of air pollution and studies have shown that in certain parts of Nigeria, trees have shown tolerance and grow in areas that have a significant amount of air pollution[124]

Environmental issues

Nigeria's Delta region, home of the large oil industry, experiences serious oil spills and other environmental problems, which has caused conflict in the Delta region.

Waste management including sewage treatment, the linked processes of deforestation and soil degradation, and climate change or global warming are the major environmental problems in Nigeria. Waste management presents problems in a megacity like Lagos and other major Nigerian cities which are linked with economic development, population growth and the inability of municipal councils to manage the resulting rise in industrial and domestic waste. This waste management problem is also attributable to unsustainable environmental management lifestyles of Kubwa community in the Federal Capital Territory, where there are habits of indiscriminate disposal of waste, dumping of waste along or into the canals, sewerage systems that are channels for water flows, and the like. Haphazard industrial planning, increased urbanisation, poverty and lack of competence of the municipal government are seen as the major reasons for high levels of waste pollution in major cities of the country. Some of the solutions have been disastrous to the environment, resulting in untreated waste being dumped in places where it can pollute waterways and groundwater.[125]

In 2005, Nigeria had the highest rate of deforestation in the world, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.[126] That year, 12.2%, the equivalent of 11,089,000 hectares had been forested in the country. Between 1990 and 2000, Nigeria lost an average of 409,700 hectares of forest every year equal to an average annual deforestation rate of 2.4%. Between 1990 and 2005, in total Nigeria lost 35.7% of its forest cover or around 6,145,000 hectares.[127] Nigeria had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.2/10, ranking it 82nd globally out of 172 countries.[128]

In the year 2010, thousands of people were inadvertently exposed to lead-containing soil from informal gold mining within the northern state of Zamfara. While estimates vary, it is thought that upwards of 400 children died of acute lead poisoning, making this perhaps the largest lead poisoning fatality outbreak ever encountered.[129]

Economy

Nigeria's mixed economy is the largest in Africa, the 26th-largest in the world by nominal GDP, and 25th-largest by PPP. It is a lower-middle-income economy,[130] with its abundant supply of natural resources, well-developed financial, legal, communications, transport sectors and Nigerian Stock Exchange. Economic development has been hindered by years of military rule, corruption, and mismanagement. The restoration of democracy and subsequent economic reforms have successfully put Nigeria back on track towards achieving its full economic potential. Next to petroleum, the second-largest source of foreign exchange earnings for Nigeria are remittances sent home by Nigerians living abroad.[131]

During the oil boom of the 1970s, Nigeria accumulated a significant foreign debt to finance major infrastructural investments. With the fall of oil prices during the 1980s oil glut, Nigeria struggled to keep up with its loan payments and eventually defaulted on its principal debt repayments, limiting repayment to the interest portion of the loans. Arrears and penalty interest accumulated on the unpaid principal, which increased the size of the debt. After negotiations by the Nigerian authorities, in October 2005 Nigeria and its Paris Club creditors reached an agreement under which Nigeria repurchased its debt at a discount of approximately 60%. Nigeria used part of its oil profits to pay the residual 40%, freeing up at least $1.15 billion annually for poverty reduction programmes. Nigeria made history in April 2006 by becoming the first African country to completely pay off its debt (estimated $30 billion) owed to the Paris Club.[citation needed]

Agriculture

As of 2010[update], about 30% of Nigerians are employed in agriculture.[132] Agriculture used to be the principal foreign exchange earner of Nigeria.[133] Major crops include beans, sesame, cashew nuts, cassava, cocoa beans, groundnuts, gum arabic, kolanut, maize (corn), melon, millet, palm kernels, palm oil, plantains, rice, rubber, sorghum, soybeans and yams.[134] Cocoa is the leading non-oil foreign exchange earner.[134] Rubber is the second-largest non-oil foreign exchange earner.[134]

Before the Nigerian civil war, Nigeria was self-sufficient in food.[134] Agriculture has failed to keep pace with Nigeria's rapid population growth, and Nigeria now relies upon food imports to sustain itself.[134] The Nigerian government promoted the use of inorganic fertilizers in the 1970s.[135] In August 2019, Nigeria closed its border with Benin and other neighbouring countries to stop rice smuggling into the country as part of efforts to boost local production.[136]

Petroleum and mining

Nigeria is the 12th largest producer of petroleum in the world, the 8th largest exporter, and has the 10th largest proven reserves. Petroleum plays a large role in the Nigerian economy, accounting for 40% of GDP and 80% of government earnings. However, agitation for better resource control in the Niger Delta, its main oil-producing region, has led to disruptions in oil production and prevents the country from exporting at 100% capacity.[137]

The Niger Delta Nembe Creek oil field was discovered in 1973 and produces from middle Miocene deltaic sandstone-shale in an anticline structural trap at a depth of 2 to 4 kilometres (7,000 to 13,000 feet).[138] In June 2013, Shell announced a strategic review of its operations in Nigeria, hinting that assets could be divested. While many international oil companies have operated there for decades, by 2014 most were making moves to divest their interests, citing a range of issues including oil theft. In August 2014, Shell said it was finalising its interests in four Nigerian oil fields.[139]

Nigeria has a total of 159 oil fields and 1,481 wells in operation according to the Department of Petroleum Resources.[140] The most productive region of the nation is the coastal Niger Delta Basin in the Niger Delta or "south-south" region which encompasses 78 of the 159 oil fields. Most of Nigeria's oil fields are small and scattered, and as of 1990, these small fields accounted for 62.1% of all Nigerian production. This contrasts with the sixteen largest fields which produced 37.9% of Nigeria's petroleum at that time.[141]

In addition to its petroleum resources, Nigeria also has a wide array of underexploited mineral resources which include natural gas, coal, bauxite, tantalite, gold, tin, iron ore, limestone, niobium, lead and zinc.[142] Despite huge deposits of these natural resources, the mining industry in Nigeria is still in its infancy.

Services and tourism

Nigeria has a highly developed financial services sector, with a mix of local and international banks, asset management companies, brokerage houses, insurance companies and brokers, private equity funds and investment banks.[143] Nigeria has one of the fastest-growing telecommunications markets in the world, with major emerging market operators (like MTN, 9mobile, Airtel and Globacom) basing their largest and most profitable centres in the country.[144] Nigeria's ICT sector has experienced a lot of growth, representing 10% of the nation's GDP in 2018 as compared to just 1% in 2001.[145] Lagos is regarded as one of the largest technology hubs in Africa with its thriving tech ecosystem.[146] Several startups like Paystack, Interswitch, Bolt and Piggyvest are leveraging technology to solve issues across different sectors.

Tourism in Nigeria centres largely on events, because of the country's ample amount of ethnic groups, but also includes rain forests, savannah, waterfalls, and other natural attractions.[147]

Abuja is home to several parks and green areas. The largest, Millennium Park, was designed by architect Manfredi Nicoletti and officially opened in December 2003. After the re-modernization project achieved by the administration of Governor Raji Babatunde Fashola, Lagos is gradually becoming a major tourist destination. Lagos is currently taking steps to become a global city. The 2009 Eyo carnival (a yearly festival originating from Iperu Remo, Ogun State) was a step toward world city status. Currently, Lagos is primarily known as a business-oriented and fast-paced community.[148] Lagos has become an important location for African and black cultural identity.[149]

Many festivals are held in Lagos; festivals vary in offerings each year and may be held in different months. Some of the festivals are Festac Food Fair held in Festac Town Annually, Eyo Festival, Lagos Black Heritage Carnival, Lagos Carnival, Eko International Film Festival, Lagos Seafood Festac Festival, LAGOS PHOTO Festival and the Lagos Jazz Series, which is a unique franchise for high-quality live music in all genres with a focus on jazz. Established in 2010, the event takes place over a 3 to 5 days period at selected high-quality outdoor venues. The music is as varied as the audience itself and features a diverse mix of musical genres from rhythm and blues to soul, Afrobeat, hip hop, bebop, and traditional jazz. The festivals provide entertainment of dance and song to add excitement to travellers during a stay in Lagos.

Lagos has sandy beaches by the Atlantic Ocean, including Elegushi Beach and Alpha Beach. Lagos also has many private beach resorts including Inagbe Grand Beach Resort and several others in the outskirts. Lagos has a variety of hotels ranging from three-star to five-star hotels, with a mixture of local hotels such as Eko Hotels and Suites, Federal Palace Hotel and franchises of multinational chains such as Intercontinental Hotel, Sheraton, and Four Points by Hilton. Other places of interest include the Tafawa Balewa Square, Festac town, The Nike Art Gallery, Freedom Park, and the Cathedral Church of Christ.

Manufacturing and technology

Nigeria has a manufacturing industry that includes leather and textiles (centred in Kano, Abeokuta, Onitsha, and Lagos). Nigeria currently has an indigenous auto manufacturing company, Innoson Vehicle Manufacturing[150] located in Nnewi. It produces buses and SUVs. Car manufacturing (for the French car manufacturer Peugeot as well as for the English truck manufacturer Bedford, now a subsidiary of General Motors), T-shirts, plastics and processed food. In this regard, some foreign vehicle manufacturing companies like Nissan have made known their plans to have manufacturing plants in Nigeria.[151] Ogun is considered to be Nigeria's current industrial hub, as most factories are located in Ogun and more companies are moving there, followed by Lagos.[152][153][154]

Nigeria has a few electronic manufacturers like Zinox, the first branded Nigerian computer, and manufacturers of electronic gadgets such as tablet PCs.[155] In 2013, Nigeria introduced a policy regarding import duty on vehicles to encourage local manufacturing companies in the country.[156][157] The city of Aba in the south-eastern part of the country is well known for handicrafts and shoes, known as "Aba made".[158]

Infrastructure

Energy

Nigeria's primary energy consumption was about 108 Mtoe in 2011. Most of the energy comes from traditional biomass and waste, which account for 83% of total primary production. The rest is from fossil fuels (16%) and hydropower (1%). Since independence, Nigeria has tried to develop a domestic nuclear industry for energy. Since 2004, Nigeria has had a Chinese-origin research reactor at Ahmadu Bello University and has sought the support of the International Atomic Energy Agency to develop plans for up to 4,000 MWe of nuclear capacity by 2027 according to the National Program for the Deployment of Nuclear Power for Generation of Electricity. In 2007, President Umaru Yar'Adua urged the country to embrace nuclear power to meet its growing energy needs. In 2017, Nigeria signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[159]

In April 2015, Nigeria began talks with Russia's state-owned Rosatom to collaborate on the design, construction and operation of four nuclear power plants by 2035, the first of which will be in operation by 2025. In June 2015, Nigeria selected two sites for the planned construction of the nuclear plants. Neither the Nigerian government nor Rosatom would disclose the specific locations of the sites, but it is believed that the nuclear plants will be sited in Akwa Ibom State and Kogi State. The sites are planned to house two plants each. In 2017 agreements were signed for the construction of the Itu nuclear power plant.

Transportation

Nigeria suffers from a lack of adequate transportation infrastructure. As of 1999, its 194,394 kilometres of road networks are the main means of transportation, of which 60,068 kilometres (37,325 mi) (including 1,194 km or 742 mi of expressways) are paved roads and 134,326 kilometres are unpaved roads of city, town and village roads. The railways have undergone a massive revamping with projects such as the Lagos-Kano Standard Gauge Railway being completed connecting northern cities of Kano, Kaduna, Abuja, Ibadan and Lagos.

There are 54 airports in Nigeria; the principal airports are Murtala Muhammed International Airport in Lagos and Nnamdi Azikiwe International Airport in Abuja. Three other international airports are Mallam Aminu Kano International Airport in Kano, Akanu Ibiam International Airport in Enugu and Port Harcourt International Airport in Port Harcourt. As with other transportation facilities, the airports suffer from a poor reputation for safety and operational efficiency.

Telecommunications

According to the National Bureau of Statistics in 2020, Nigeria has about 136,203,231 internet users out of an estimated population of 205,886,311.[160] This implies that as of 2020, 66 per cent of the Nigerian population are connected to the internet and using it actively. Although Nigerians are using the internet for educational, social networking, and entertainment purposes, the internet has also become a tool for mobilizing political protests in Nigeria. However, the Nigerian government has become threatened by how its citizens are using the internet to influence governance and political changes. Using various measures including but not limited to Illegal arrest, taking down of websites, passport seizures, and restricted access to bank accounts, the Nigerian Government punishes citizens for expressing themselves on the internet and working to stifle internet freedom.[161]

Due to how the Nigerian government is responding to internet freedom among other things such as limitations to internet access and violations of users rights, Nigeria ranked 26th out of the 65 countries evaluated for internet freedom in the Freedom House 2020 Index.[162]

Government satellites

The government has recently begun expanding this infrastructure to space-based communications. Nigeria has a space satellite that is monitored at the Nigerian National Space Research and Development Agency Headquarters in Abuja. The Nigerian government has commissioned the overseas production and launch of four satellites.

NigComSat-1 was the first Nigerian satellite built, was Nigeria's third satellite, and Africa's first communication satellite. It was launched in 2007 aboard a Chinese Long March 3B carrier rocket, from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in China. The spacecraft was operated by NigComSat and the Nigerian Space Research and Development Agency. On 11 November 2008, NigComSat-1 failed in orbit after running out of power because of an anomaly in its solar array. It was based on the Chinese DFH-4 satellite bus and carries a variety of transponders: four C-band; fourteen Ku-band; eight Ka-band; and two L-band. It was designed to provide coverage to many parts of Africa, and the Ka-band transponders would also cover Italy. The satellite was launched from Russia on 27 September 2003. Nigeriasat-1 was part of the worldwide Disaster Monitoring Constellation System.[163] The primary objectives of the Nigeriasat-1 were: to give early warning signals of environmental disaster; to help detect and control desertification in the northern part of Nigeria; to assist in demographic planning; to establish the relationship between malaria vectors and the environment that breeds malaria and to give early warning signals on future outbreaks of meningitis using remote sensing technology; to provide the technology needed to bring education to all parts of the country through distant learning, and to aid in conflict resolution and border disputes by mapping out state and International borders.

NigeriaSat-2, Nigeria's second satellite, was built as a high-resolution earth satellite by Surrey Space Technology Limited, a United Kingdom-based satellite technology company. It has 2.5-metre resolution panchromatic (very high resolution), 5-metre multispectral (high resolution, NIR red, green and red bands), and 32-metre multispectral (medium resolution, NIR red, green and red bands) antennas, with a ground receiving station in Abuja. The NigeriaSat-2 spacecraft alone was built at a cost of over £35 million. This satellite was launched into orbit by a military base in China.[164] On 10 November 2008 (0900 GMT), the satellite was reportedly switched off for analysis and to avoid a possible collision with other satellites. According to Nigerian Communications Satellite Limited, it was put into "emergency mode operation to effect mitigation and repairs".[165] The satellite eventually failed after losing power on 11 November 2008. On 24 March 2009, the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Science and Technology, NigComSat Ltd. and CGWIC signed another contract for the in-orbit delivery of the NigComSat-1R satellite. NigComSat-1R was also a DFH-4 satellite, and the replacement for the failed NigComSat-1 was successfully launched into orbit by China in Xichang on 19 December 2011.[166][167] The satellite was stated to have a positive impact on national development in various sectors such as communications, internet services, health, agriculture, environmental protection and national security.[168]

NigeriaEduSat-1 was a satellite designed, built, and owned by the Federal University of Technology Akure (FUTA), in conjunction with Nigeria's National Space Research and Development Agency and Japan's Kyushu Institute of Technology. It was equipped with 0.3-megapixel and 5-megapixel cameras, and with the rest of the satellite, the fleet took images of Nigeria. The satellite transmitted songs and poems as an outreach project to generate Nigerian interest in science. The signal could be received by amateur radio operators. The satellite constellation also conducted measurements of the atmospheric density 400 kilometres (1.3 million feet) above the Earth. The satellite cost about US$500,000 to manufacture and launch.

Demographics

| Population in Nigeria[169][170] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1971 | 55 | ||

| 1980 | 71 | ||

| 1990 | 95 | ||

| 2000 | 125 | ||

| 2004 | 138 | ||

| 2008 | 151 | ||

| 2012 | 167 | ||

| 2016 | 186 | ||

| 2017 | 191 | ||

The United Nations estimates that the population of Nigeria in 2021 was at 213,401,323[171][172], distributed as 51.7% rural and 48.3% urban, and with a population density of 167.5 people per square kilometre. Around 42.5% of the population were 14 years or younger, 19.6% were aged 15–24, 30.7% were aged 25–54, 4.0% were aged 55–64, and 3.1% were aged 65 years or older. The median age in 2017 was 18.4 years.[173] Nigeria is the seventh most populous country in the world. The birth rate is 35.2-births/1,000 population and the death rate is 9.6 deaths/1,000 population as of 2017, while the total fertility rate is 5.07 children born/woman.[173] Nigeria's population increased by 57 million from 1990 to 2008, a 60% growth rate in less than two decades.[174] Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and accounts for about 17% of the continent's total population as of 2017; however, exactly how populous is a subject of speculation.[175]

National census results in the past few decades have been disputed. The results of the most recent census were released in December 2006 and gave a population of 140,003,542. The only breakdown available was by gender: males numbered 71,709,859, females numbered 68,293,008. According to the United Nations, Nigeria has been undergoing explosive population growth and has one of the highest growth and fertility rates in the world. By their projections, Nigeria is one of eight countries expected to account collectively for half of the world's total population increase in 2005–2050.[176] The UN estimates that by 2100 the Nigerian population will be between 505 million and 1.03 billion people (middle estimate: 730 million).[177] In 1950, Nigeria had only 33 million people. In 2012, President Goodluck Jonathan said Nigerians should limit their number of children.[178]

Millions of Nigerians have emigrated during times of economic hardship, primarily to Europe, North America and Australia. It is estimated that over a million Nigerians have emigrated to the United States and constitute the Nigerian American populace. Individuals in many such Diasporic communities have joined the "Egbe Omo Yoruba" society, a national association of Yoruba descendants in North America.[179][180] Nigeria's largest city is Lagos. Lagos has grown from about 300,000 in 1950[181] to an estimated 13.4 million in 2017.[182]

Ethnic groups

|

|

|

| A Hausa xalam player | Igbo Chief | Yoruba drummers |

Nigeria has more than 250 ethnic groups, with varying languages and customs, creating a country of rich ethnic diversity. The three largest ethnic groups are the Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo, together accounting for more than 70% of the population, while the Edo, Ijaw, Fulɓe, Kanuri, Urhobo-Isoko, Ibibio, Ebira, Nupe, Gbagyi, Jukun, Igala, Idoma and Tiv comprise between 25 and 30%; other minorities make up the remaining 5%.[183] The Middle Belt of Nigeria is known for its diversity of ethnic groups, including the Atyap, Berom, Goemai, Igala, Kofyar, Pyem, and Tiv. The official population count of each of Nigeria's ethnicities is disputed as members of different ethnic groups believe the census is rigged to give a particular group (usually believed to be northern groups) numerical superiority.[113][184][185]

There are small minorities of British, American, Indian, Chinese (est. 50,000),[186] white Zimbabwean,[187] Japanese, Greek, Syrian and Lebanese immigrants. Immigrants also include those from other West African or East African nations. These minorities mostly reside in major cities such as Lagos and Abuja, or the Niger Delta as employees for the major oil companies. Several Cubans settled in Nigeria as political refugees following the Cuban Revolution.

In the middle of the 19th century, several ex-slaves of Afro-Cuban and Afro-Brazilian descent[188] and emigrants from Sierra Leone established communities in Lagos and other regions of Nigeria. Many ex-slaves came to Nigeria following the emancipation of slaves in the Americas. Many of the immigrants, sometimes called Saro (immigrants from Sierra Leone) and Amaro (ex-slaves from Brazil)[189] later became prominent merchants and missionaries in these cities.

Languages

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

521 languages have been spoken in Nigeria; nine of them are extinct.[dubious ] In some areas of Nigeria, ethnic groups speak more than one language. The official language of Nigeria, English, was chosen to facilitate the cultural and linguistic unity of the country, owing to the influence of British colonisation which ended in 1960. Many French speakers from surrounding countries have influenced the English spoken in the border regions of Nigeria and some Nigerian citizens have become fluent enough in French to work in the surrounding countries. The French spoken in Nigeria may be mixed with some native languages. French may also be mixed with English.

The major languages spoken in Nigeria represent three major families of languages of Africa: the majority are Niger-Congo languages, such as Igbo, Yoruba, Ijaw, Fulfulde, Ogoni, and Edo. Kanuri, spoken in the northeast, primarily in Borno and Yobe State, is part of the Nilo-Saharan family, and Hausa is an Afroasiatic language. Even though most ethnic groups prefer to communicate in their languages, English as the official language is widely used for education, business transactions and official purposes. English as a first language is used by only a small minority of the country's urban elite, and it is not spoken at all in some rural areas. Hausa is the most widely spoken of the three main languages spoken in Nigeria.

With the majority of Nigeria's populace in the rural areas, the major languages of communication in the country remain indigenous languages. Some of the largest of these, notably Yoruba and Igbo, have derived standardised languages from several different dialects and are widely spoken by those ethnic groups. Nigerian Pidgin English, often known simply as "Pidgin" or "Broken" (Broken English), is also a popular lingua franca, though with varying regional influences on dialect and slang. The pidgin English or Nigerian English is widely spoken within the Niger Delta Region.[190]

Religion

Nigeria is a religiously diverse society, with Islam and Christianity being the most widely professed religions. Nigerians are nearly equally divided into Muslims and Christians, with a tiny minority of adherents of traditional African religions and other religions.[192] The Christian share of Nigeria's population is on the decline because of the lower fertility rate compared to Muslims in the north.[193] As in other parts of Africa where Islam and Christianity are dominant, religious syncretism with the traditional African religions is common.[194]

A 2012 report on religion and public life by the Pew Research Center stated that in 2010, 49.3 per cent of Nigeria's population was Christian, 48.8 per cent was Muslim, and 1.9 per cent were followers of indigenous and other religions or unaffiliated.[195] However, in a report released by Pew Research Center in 2015, the Muslim population was estimated to be 50%, and by 2060, according to the report, Muslims will account for about 60% of the country.[196] The 2010 census of Association of Religion Data Archives has also reported that 48.8% of the total population was Christian, slightly larger than the Muslim population of 43.4%, while 7.5% were members of other religions.[197] However, these estimates should be taken with caution because sample data is mostly collected from major urban areas in the south, which are predominantly Christian.[198][199][200]

Islam dominates North-Western Nigeria (Hausa, Fulani and others), with 99% Muslim, and a good portion of Northern Eastern Nigeria (Kanuri, Fulani and other groups) Nigeria. In the west, the Yoruba tribe is predominantly split between Muslims and Christians with 10% adherents of traditional religions. Protestant and locally cultivated Christianity are widely practised in Western areas, while Roman Catholicism is a more prominent Christian feature of South Eastern Nigeria. Both Roman Catholicism and Protestantism are observed in the Ibibio, Anaang, Efik, Ijo and Ogoni lands of the south. The Igbos (predominant in the east) and the Ijaw (south) are 98% Christian, with 2% practising traditional religions.[201] The middle belt of Nigeria contains the largest number of minority ethnic groups in Nigeria, who were found to be mostly Christians and members of traditional religions, with a small proportion of Muslims.[202]

Nigeria has the largest Muslim population in sub-Saharan Africa. The vast majority of Muslims in Nigeria are Sunni belonging to the Maliki school of jurisprudence; however, a sizeable minority also belongs to Shafi Madhhab. A large number of Sunni Muslims are members of Sufi brotherhoods. Most Sufis follow the Qadiriyya, Tijaniyyah or the Mouride movements. A significant Shia minority exists. Some northern states have incorporated Sharia law into their previously secular legal systems, which has brought about some controversy.[203] Kano State has sought to incorporate Sharia law into its constitution.[204] The majority of Quranists follow the Kalo Kato or Quraniyyun movement. There are also Ahmadiyya and Mahdiyya minorities,[205] as well as followers of the Baháʼí Faith.[206][207]

Among Christians, the Pew Research survey found that 74% were Protestant, 25% were Catholic, and 1% belonged to other Christian denominations, including a small Orthodox Christian community.[208] Leading Protestant churches in the country include the Church of Nigeria of the Anglican Communion, the Assemblies of God Church, the Nigerian Baptist Convention and The Synagogue, Church Of All Nations. Since the 1990s, there has been significant growth in many other churches, independently started in Africa by Africans, particularly the evangelical Protestant ones. These include the Redeemed Christian Church of God, Winners' Chapel, Christ Apostolic Church (the first Aladura Movement in Nigeria), Living Faith Church Worldwide, Deeper Christian Life Ministry, Evangelical Church of West Africa, Mountain of Fire and Miracles, Christ Embassy, Lord's Chosen Charismatic Revival Movement, Celestial Church of Christ, and Dominion City.[209] In addition, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Aladura Church, the Seventh-day Adventist and various indigenous churches have also experienced growth.[210][211] The Yoruba area contains a large Anglican population, while Igboland is a mix of Roman Catholics, Protestants, and a small population of Igbo Jews. The Edo area is composed predominantly of members of the Assemblies of God, which was introduced into Nigeria by Augustus Ehurie Wogu and his associates at Old Umuahia.

Nigeria has become an African hub for the Grail Movement and the Hare Krishnas,[212] and the largest temple of the Eckankar religion is in Port Harcourt, Rivers State, with a total capacity of 10,000.

Health

Health care delivery in Nigeria is a concurrent responsibility of the three tiers of government in the country, and the private sector.[213] Nigeria has been reorganising its health system since the Bamako Initiative of 1987, which formally promoted community-based methods of increasing accessibility of drugs and health care services to the population, in part by implementing user fees.[214] The new strategy dramatically increased accessibility through community-based health care reform, resulting in more efficient and equitable provision of services. A comprehensive approach strategy was extended to all areas of health care, with subsequent improvement in the health care indicators and improvement in health care efficiency and cost.[215]

HIV/AIDS rate in Nigeria is much lower compared to the other African nations such as Botswana or South Africa whose prevalence (percentage) rates are in the double digits. As of 2019[update], the HIV prevalence rate among adults ages 15–49 was 1.5 per cent.[216] The life expectancy in Nigeria is 54.7 years on average,[216] and 71% and 39% of the population have access to improved water sources and improved sanitation, respectively.[217] As of 2019[update], the infant mortality is 74.2 deaths per 1,000 live births.[218]

In 2012, a new bone marrow donor program was launched by the University of Nigeria to help people with leukaemia, lymphoma, or sickle cell disease to find a compatible donor for a life-saving bone marrow transplant, which cures them of their conditions. Nigeria became the second African country to have successfully carried out this surgery.[219] In the 2014 Ebola outbreak, Nigeria was the first country to effectively contain and eliminate the Ebola threat that was ravaging three other countries in the West African region; the unique method of contact tracing employed by Nigeria became an effective method later used by countries such as the United States when Ebola threats were discovered.[220][221][222]

The Nigerian health care system is continuously faced with a shortage of doctors known as "brain drain", because of emigration by skilled Nigerian doctors to North America and Europe. In 1995, an estimated 21,000 Nigerian doctors were practising in the United States alone, which is about the same as the number of doctors working in the Nigerian public service. Retaining these expensively trained professionals has been identified as one of the goals of the government.[223]

Education

Education in Nigeria is overseen by the Ministry of Education. Local authorities take responsibility for implementing policy for state-controlled public education and state schools at a regional level. The education system is divided into kindergarten, primary education, secondary education and tertiary education. After the 1970s oil boom, tertiary education was improved so it would reach every subregion of Nigeria. 68% of the Nigerian population is literate, and the rate for men (75.7%) is higher than that for women (60.6%).[224]