Phillips Exeter Academy

42°58′48″N 70°57′04″W / 42.98000°N 70.95111°W

| Phillips Exeter Academy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | |

| |

20 Main Street , 03833 United States | |

| Information | |

| Type | Independent, day & boarding |

| Motto | Non Sibi (Not for Oneself) Finis Origine Pendet (The End Depends Upon the Beginning) Χάριτι Θεοῦ (By the Grace of God) |

| Established | 1781 |

| Founder | John Phillips Elizabeth Phillips[nb 1] |

| CEEB code | 300185 |

| Principal | William K. Rawson (interim)[2] |

| Faculty | 217 |

| Gender | Coeducational |

| Enrollment | 1,079 total 865 boarding 214 day |

| Average class size | 12 students |

| Student to teacher ratio | 5:1 |

| Campus | Town, 672 acres (2.72 km2) 132 buildings |

| Color(s) | Maroon and Grey |

| Athletics | 22 Interscholastic sports 62 Interscholastic teams |

| Athletics conference | NEPSAC SSL |

| Team name | Big Red |

| Rival | Phillips Academy, Andover |

| Accreditation | NAIS TABS |

| Newspaper | The Exonian |

| Yearbook | PEAN |

| Endowment | $1.25 billion (as of June 2017)[5] |

| Budget | $93 million (2014–2015)[4] |

| Annual tuition | $53,271 (boarding) $41,608 (day)[6] |

| Affiliations | Eight Schools Association G20 Schools Ten Schools Admissions Organization |

| Alumni | Exonians |

| Website | www |

Phillips Exeter Academy (often called Exeter or PEA) is a coeducational independent school for boarding and day students in grades 9 through 12, and offers a postgraduate program. Located in Exeter, New Hampshire, it is one of the oldest secondary schools in the United States. Exeter is based on the Harkness education system, a conference format of student interaction with minimal teacher involvement. It has the largest endowment of any New England boarding school, which as of June 30, 2017, was valued at $1.25 billion.[7][8]

Phillips Exeter Academy has educated several generations of the New England establishment and prominent American politicians, but has introduced many programs to diversify the student population, including free tuition for families whose income is $75,000 or less. In 2015–2016, over 45% of students received financial aid from grants totaling over $19 million. The school has been historically highly selective, with an acceptance rate of 17% for the 2017–2018 school year, and many graduates attend the Ivy League universities among others.[9][10]

Management of the school's financial and physical resources is overseen by trustees drawn from alumni. Day-to-day operations are headed by a principal, who is appointed by the trustees. The faculty of the school are responsible for governing matters relating to student life, both in and out of the classroom.[11]

The school's first enrolled class counted 56 boys;[12] in 1970, when the decision was made to implement co-education, there were 700 boys.[13] The 2018 Academic Year saw enrollment at 1,095 students with 884 boarding students and 211 day students.[14] The student body is composed of a roughly equal ratio of male and female students who are housed in 25 single-sex dormitories and 2 coed dormitories. Each residence is supervised by a dormitory head selected from the faculty.

History

Origins

Phillips Exeter Academy was established in Exeter, New Hampshire in 1781 by Elizabeth and John Phillips. John Phillips had made his fortune as a merchant and banker before going into public service, and financially supported his nephew Samuel Phillips, Jr. in founding his own school, Phillips Academy, in Andover, Massachusetts, three years earlier. As a result of this family relationship, the two schools share a rivalry.[15] The school that Phillips founded at Exeter was to educate students under a Calvinist religious framework. However, like his nephew who founded Andover, Phillips stipulated in the school's founding charter that it would "ever be equally open to youth of requisite qualifications from every quarter."[12]

Phillips had previously been married to Sarah Gilman, wealthy widow of Phillips' cousin, merchant Nathaniel Gilman,[16] whose large fortune, bequeathed to Phillips, enabled him to endow the academy.[17] The Gilman family also donated to the academy much of the land on which it stands, including the initial 1793 grant by New Hampshire Governor John Taylor Gilman of the Yard, the oldest part of campus; the academy's first class in 1783 included seven Gilmans.[18][19] In 1814, Nicholas Gilman, signer of the U.S. Constitution, left $1,000 to Exeter to teach "sacred music."[20]

The academy's first schoolhouse, the First Academy Building, was built on a site on Tan Lane in 1783, and today stands not far from its original location. The building was dedicated on February 20, 1783, the same day that the school's first Preceptor, William Woodbridge, was chosen by John Phillips.[12]

Exeter's Deed of Gift, written by John Phillips at the founding of the school, states that Exeter's mission is to instill in its students both goodness and knowledge:

"Above all, it is expected that the attention of instructors to the disposition of the minds and morals of the youth under their charge will exceed every other care; well considering that though goodness without knowledge is weak and feeble, yet knowledge without goodness is dangerous, and that both united form the noblest character, and lay the surest foundation of usefulness to mankind."[15]

Harkness gift

On April 9, 1930, philanthropist and oil magnate Edward Harkness wrote to Exeter Principal Lewis Perry regarding how a substantial donation that Harkness would make to the Academy might be used to fund a new way of teaching and learning:

What I have in mind is a classroom where students could sit around a table with a teacher who would talk with them and instruct them by a sort of tutorial or conference method, where each student would feel encouraged to speak up. This would be a real revolution in methods.[21]

The result was "Harkness teaching", in which a teacher and a group of students work together, exchanging ideas and information, similar to the Socratic method. In November 1930, Harkness gave Exeter $5.8 million to support this initiative. Since then, the Academy's principal mode of instruction has been by discussion, "seminar style," around an oval table known as the Harkness table.[22][23]

Student body

Exeter participated in the Chinese Educational Mission, hosting seven students from Qing China, starting in 1879. They were sent to learn about western technology, and attended Exeter among other schools to prepare for college. However, all students were recalled in 1881 due to mounting tensions between the United States and China, as well as growing realization that the students were becoming Americanized.[24]

The Academy became coeducational in 1970 when 39 girls began attending.[13][25] Today the student body is roughly half boys and half girls. In 1996, to reflect the Academy's coeducational status, a new gender-inclusive Latin inscription Hic Quaerite Pueri Puellaeque Virtutem et Scientiam ("Here, boys and girls, seek goodness and knowledge") was added over the main entrance to the Academy Building. This new inscription augments the original one – Huc Venite, Pueri, ut Viri Sitis ("Come hither boys so that ye may become men").[26]

Academics

Exeter uses an 11-point grading system, in which an A is worth 11 points and an E is worth 0 points. Exeter has a student-to-teacher ratio of about 5:1.[27] A majority of the faculty have advanced degrees in their fields.[28] Students who attend Exeter for four years are required to take courses in the arts, classical or modern languages, computer science, English, health & human development, history, mathematics, religion, and science. Most students receive an English diploma, but students who take the full series of Latin and Ancient Greek classes receive a Classical diploma.[29]

Harkness teaching method

Most classes at Exeter are taught around Harkness tables. No classrooms have rows of chairs, and lectures are rare. The completion of the Phelps Science Center in 2001 enabled all science classes, which previously had been taught in more conventional classrooms, to be conducted around the same Harkness tables.[30] Elements of the Harkness method, including the Harkness table, are now used in schools around the world.[31][32]

Notable faculty

- Founder of the Religion department Frederick Buechner, minister and author[33]

- Instructor in History Michael Golay, historian and author[34]

- Instructor in English Todd Hearon, poet[35]

- Instructor in English Willie Perdomo, poet and children's book author[36]

- Instructor in Mathematics Zuming Feng, U.S. International Mathematical Olympiad Program team coach from 1997 to 2013[37]

- Instructor in Mathematics Gwynneth Coogan, former Olympic athlete[38]

- Instructor in Music Marilinda Garcia, member of the New Hampshire House of Representatives and harp player[39]

- Instructor in Physical Education Olutoyin Augustus, former Olympic athlete[40]

Off-campus study

During Exeter's tenth principal, Richard W. Day's tenure, the Washington Intern Program and the Foreign Studies Program began.[41] Exeter offers the Washington Intern Program, where students intern in the office of a senator or congressional representative.[42][43] Exeter also participates in the Milton Academy Mountain School program,[44] which allows students to study in a small rural setting in Vershire, Vermont.[45] The academy currently sponsors trimester-long foreign study programs in Grenoble, Tema, Tokyo, Saint Petersburg, Stratford-upon-Avon, Eleuthera, Taichung, Göttingen, Rome, Cuenca, and Callan;[44] as well as school-year abroad programs in Beijing, Rennes, Viterbo, and Zaragoza.[46][47] The academy also offers foreign language summer programs in France, Japan, Spain, and Taiwan.

Matriculation

Around a third of Exeter students matriculate into the Ivy League, MIT, and Stanford.[9][10] The five most common college destinations of the classes of 2013–2015 were Columbia (36), Harvard (33), Yale (32), Georgetown (26), and NYU (26).[48]

Student body

The Academy claims a tradition of diversity.[49] During the Civil War, four white students from Kentucky confronted the then-principal Gideon Lane Soule over the presence of a black student at Exeter. When they demanded that the black student be expelled on account of his skin color, Soule replied, "The boy is to stay; you may do as you please."[50][51]

One of Exeter's unofficial mottoes – "Youth from Every Quarter" – is taken from the Deed of Gift, and is widely quoted and emphasized in the introductory course for freshmen in the fall.[52] This phrase has also guided the Academy's admissions policies. Exeter's longtime Director of Scholarships H. Hamilton "Hammy" Bissell (1929) worked for decades to enable qualified students from all over the U.S. to attend Exeter.[53]

For the 2016–17 school year, the Exeter student body included students from 45 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, and 34 countries. Students of non-European descent comprise 41% of the student body[54] (Asian 23%, Black 9%, Hispanic/Latino 8%, Native American 1%).[55] Legacy students account for 13% of the students. Of new students entering in 2017 (a total of 353), 53% attended public school and 47% attended private, parochial, military, home, or foreign schools.[56]

Most Exeter students—80 percent—live on campus in dormitories or houses. The remaining 19 percent of the student body are day students from the surrounding communities.[57]

The Academy uses a unique designation for its grade levels. Entering first-year students are called Juniors (nicknamed "preps"), second-year students are Lower Middlers ("lowers"), third-year students are Upper Middlers ("uppers"), and fourth-year students are seniors. Exeter also admits postgraduate students ("PGs").[58]

Finances

Tuition and financial aid

Tuition to Exeter has increased at rate of 4.11% a year since the 2002 academic year, or 3.47% per year over the last decade. There are mandatory fees for boarding students and optional fees on top of tuition.[59]

Exeter offers needs-based financial aid. Since 2008, students whose family income is $75,000 or less have received a free education, including tuition, room and board, travel, a laptop, and other miscellaneous expenses;[60] many families earning up to $200,000 receive partial assistance. Since 2007, financial aid has been entirely in the form of grants that do not need to be repaid. From 2004–2008, Exeter admissions were effectively needs-blind, but in 2008, the school announced that the decline in its endowment forced it to suspend that policy.[61]. In 2018, approximately 50 percent of students receive financial assistance each year.[62]

A previous President of the Academy's Trustees, Charles T. "Chuck" Harris III, a former Goldman Sachs managing partner, attended Exeter on full scholarship. "Everything I am is a result of that experience," Harris has said of financial aid, "and I'd like to think there's some opportunity like that for every kid in the world."[63]

Endowment

Exeter's endowment as of June 30, 2017, was valued at $1.25 billion.[8] This is the third-highest endowment of any American secondary school, behind the $11.0 billion endowment of Kamehameha Schools in Hawaii,[64] and the $7.8 billion of the Milton Hershey School in Pennsylvania. Due largely to the successful investments of the school and gifts from wealthy alumni, the school has an endowment of just under $1 million per student.[65]

According to The New York Times, Exeter devotes an average of $63,500 annually to each of its students, an amount well above the 2007-8 annual tuition of $36,500.[65] This money is spent on operating expenses, small classes (with a typical student-teacher ratio of no more than 12 to one), computers for students, financial aid, and Exeter's facilities, which include a swimming pool, two hockey rinks, and the largest secondary-school library in the world. Exeter also has a high-quality cafeteria, which serves such fare as made-to-order omelets for breakfast.[65]

Campus facilities

Academic facilities

- The Academy Building is the fourth such building. It was built in 1914 after a devastating fire ruined the third. The Academy Building was designed by Ralph Adams Cram of Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson,[66] and houses the History, Math, Religion and Classical Languages departments, along with a small but significant archaeology/anthropology museum.[67] Two wings were added to the original structure in the 1920s and 1930s during a building boom that was orchestrated by Principal Lewis Perry. One of these wings is the Mayer Art Center, which, despite being attached to the Academy Building, is often referred to as a separate building. The Academy Building also houses the Assembly Hall (formerly known as the Chapel). In former times, non-denominational, Christian religious services were conducted in the Chapel every morning Monday through Saturday before the beginning of classes, and attendance was mandatory for all students in keeping with the wishes of the founders of the academy. The bell (visible in the photo of the Academy Building tower) was rung in a succession of rings to call the student body to worship: Ones, Twos, Threes, Fours, and Fives. After Fives were rung, monitors would begin walking down the rows checking attendance on the benches. The bell continues to be rung to mark the end of classes, as well as to mark each hour from 8 AM to 11 PM.

- The Class of 1945 Library, a famous modern library designed by Louis Kahn. The library has a shelf capacity of 250,000 volumes, and as of 2009 housed 162,000 volumes. This library is the largest secondary-school library in the world.[68] When it opened, Ada Louise Huxtable, architecture critic for The New York Times, hailed the Exeter library as a "serene, distinguished structure of considerable beauty." She said that the library's central space "breaks on the viewer with breathtaking drama." The headline of her review called the Exeter library a "stunning paean to books."[69]

- Elizabeth Phillips Academy Center (or "EPAC") is the student center of the campus. It houses the Phelps Commons, the McLane Post Office, the Day Student Lounge, the Forum (a 300-person auditorium), the Academic Support Center, and a grill. It also plays host to a number of student organizations such as The Exonian, WPEA, and the Exeter Student Service Organization (ESSO). The building was originally opened in 2006 as the Phelps Academy Center, but the name was changed in the fall of 2018.[70]

- Goel Center for Theater and Dance was opened in 2018. It houses DRAMAT, the student led drama club at Exeter. It is named for David Goel and Stacey Goel.[71]

- Phillips Hall is home to the English and Modern Languages departments. On the first floor of Phillips Hall is the Elting Room (where the faculty meets). Phillips Hall was built in 1932 during the tenure of Principal Lewis Perry. The Harkness gift funded the building, and its classrooms were designed for the Harkness tables.

- Phelps Science Center was designed by Centerbrook Architects, and was built in 2001. The center provides laboratory and classroom space. In 2004, it received the American Institute of Architects New Hampshire's Honor Award for Excellence in Architecture.[72]

- Forrestal Bowld Music Center houses the Music Department, the Music Library, three rehearsal halls, several faculty offices, and dozens of rehearsal rooms.[73] It was built in 1995, and was awarded the Honor Award in Architecture Design by the Boston Society of Architects in 1996. It is connected to the Phelps Science Center by an archway titled "Simple Gifts," which was designed by Jim Sardonis and serves as an entryway to Fisher Theater.[20]

- Fisher Theater is home to the Drama Department, Shakespeare Society, and the Dramatic Association (DRAMAT), a student organization. It includes a 100-seat blackbox theater and a 225-seat main stage.[74]

- Mayer Art Center is home to the Art Department and the Lamont Gallery, as well as the College Counseling Office. It was constructed in 1903 as Alumni Hall. It contains a large ceramics studio with approximately twenty wheels and three kilns on the first floor, two printmaking studios and three drawing/painting studios on the second floor, and an architectural and 3-D design studio on the third floor. It also has a 3-D printer, which was added in 2013.

Athletic facilities

- The George H. Love Gymnasium was built in 1969, and is named for George H. Love (1917).[75] It houses squash facilities with 10 international sized courts, one swimming pool, three basketball courts, a weight-training room, a sports-science lab, gym offices, two hockey rinks, locker rooms, and visiting team locker rooms.[76]

- The Thompson Gymnasium was built in 1918, replacing the old gym which was demolished in 1922, and was a gift of Colonel William Boyce Thompson (1890). It has a basketball court, a dance studio, visiting team locker rooms, a cycling training room, a second swimming pool and a media room.[66]

- The Thompson Cage was built in 1931 and was also a gift of Colonel Thompson. It is an indoor cage with two tracks; one has a wooden surface and the other a dirt surface. The open dirt-surfaced floor is a multipurpose area. A wrestling room and gymnastics space are attached. In 2015, Academy Trustees approved the removal of the Cage and the construction of a new field house in its footprint.

- The Thompson Fieldhouse was opened in 2018 on the grounds of the former Thompson Cage. It is a 84,574 square-foot facility connected to the Love and Thompson Gymnasiums, housing four indoor tennis courts, two batting cages, a wrestling room, and an indoor track.[77][78]

- Ralph Lovshin Track is an outdoor all-weather 400-m track named for the long-serving track coach Ralph Lovshin.

- The Plimpton Playing Fields are used for various outdoor sports. They are named in honor of alumnus and trustee George Arthur Plimpton (1873).[66]

- Phelps Stadium is used for football, soccer, lacrosse and field hockey. It was converted into turf surface in 2006.

- The William G. Saltonstall Boathouse was built in 1990, and is the center of crew on campus, on the Squamscott River. It is named for the academy's ninth principal.[66]

- Amos Alonzo Stagg Baseball Diamond was named after alumnus Amos Alonzo Stagg.

- Hilliard Lacrosse Field

- Roger Nekton Championship Pool is named for the long-serving former swimming and water polo coach.

- The Downer Family Fitness Center was built in 2015 guided by a donation from its namesake, the Downer family. It features many weight lifting resources, aerobic machines, and turf space.

- 19 outdoor tennis courts

- Several miles of cross-country and running trails

- Wrestling practice room[79]

Other facilities

- Phillips Church was originally built as the Second Parish Church in 1897 and was purchased by the Academy in 1922.[66] The building was designed by Ralph Adams Cram. Although originally a church, the building now contains spaces for students of many faiths. It includes a Hindu shrine, a Muslim prayer room and ablutions fountain, a kosher kitchen, and a meditation room. Services that are particular to Phillips Church include Evening Prayer on Tuesday nights, Thursday Meditation, and Indaba—a religious open forum.

- Nathaniel Gilman House was built in 1740. The Gilman House is a large colonial white clapboard home with a gambrel roof hipped at one end, a leaded fanlight over the front door and a wide panelled entry hall.[80] This home, as well as the Benjamin Clark Gilman House which is also owned by the Academy, were built for members of Exeter's Gilman family, who donated the Nathaniel Gilman House to the academy in 1905. The home now houses the academy's Alumni and Alumnae Affairs and Development Office.

- The Davis Center was designed by Ralph Adams Cram as the Davis Library. Today it houses the financial aid offices as well as the dance studio.

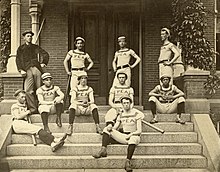

Athletics

Exeter first organized its PEA Baseball Club on October 19, 1859, and on September 6, 1875, Exeter had the first meeting of the Phillips Exeter Academy Athletic Association. Captains of all Exeter's athletic teams were awarded the right to display Exeter's "E" on their sweaters, along with a certificate from the Phillips Exeter Academy Athletic Association authenticating their rights in writing.[15] The school's traditional rival is Phillips Academy (Andover), and the annual Exeter–Andover Football game has been played since 1878. Similar boarding school traditions include the Choate–Deerfield rivalry and Hotchkiss–Taft rivalry.

Students are required to participate in intramural or interscholastic athletic programs. The school offers 65 interscholastic teams at the varsity and junior varsity level as well as 27 intramural sports squads. Other various fitness classes are also offered.

Interscholastic sports

|

Fall

|

Winter

|

Spring

|

Opponents

Exeter's main rival is Phillips Academy (Andover). Exeter defeated Andover 12–0 in the first ever baseball game played between these two academies on May 2, 1878. Andover, in turn, defeated Exeter 22–0 in football on November 2, 1878. One of Exeter's most notable football games took place in 1913 with a 59–0 victory over Andover. Exeter and Andover have competed nearly every year in football since 1878;[81] currently Andover leads in the number of games won, including the most recent meeting between the schools on November 8, 2014.

Other athletic opponents include New England schools such as Belmont Hill School, Berwick Academy, Deerfield Academy, Northfield Mount Hermon, Brewster Academy, Choate Rosemary Hall, Groton School, The Governor's Academy, Loomis Chaffee, Tabor Academy, Milton Academy, Avon Old Farms, Worcester Academy, Cushing Academy, and various other northeastern prep and boarding schools.[82]

Championships

The boys' water polo team has won twenty-two New England prep school championships. Until winter of 2008, boys' swimming had won 15 of the last 17 New England championships, placing runner-up both losing years. The cycling team is the defending champion. Wrestling has won the New England tournament 13 times.

Exeter is a fixture in New England championship tournaments in nearly all sports, missing the championship in both boys' and girls' soccer in 2005, and winning the New England Class A Championship in football in 2003 and 2009. In 2007, the boys' squash team finished second at the New England Division A Interscholastic Championship and fourth at the National High School Team Tournament. Both the men's and women's cross country teams have won the Division 1 NEPSTA Championship multiple times in the past decade, with the boys' team winning four straight titles from 2011–2014. The wrestling team has won more Class A and New England Prep School Wrestling Association titles than any other team, most recently winning the Class A tourney in 2007 and 2003 and the New England tourney in 2001. It has also crowned a National Prep Wrestling champion, Rei Tanaka, in 1990. Both the girls' and boys' ice hockey teams have won New England championships recently.

When future major league baseball player Sam Fuld attended Phillips Exeter Academy, he led the baseball team to a league title as a junior in 1999, as he batted .600.[83] Fuld was named a 2000 Pre-season First Team All-American by Baseball America, Collegiate Baseball, USA Today, and Fox Sports.[83] He was also listed 19th among the 100 Top High School Prospects of 2000 by Baseball America, and selected the New Hampshire 2000 Gatorade High School Player of the Year.[83][84][85]

The boys' crew took first and fourth place at the U.S. Rowing Junior National Championships in 1996, 2002 and 2008 respectively.[86] In 2012 the boys' crew went to Henley-on-Thames in England to compete, but did not make it past heats. The boys' crew was the first organized sport at Exeter, and over its more than 100 years of competition has produced several Olympians, National Team members and numerous Division I rowers.

The girls' team took sixth place at the 2006 U.S Rowing National championships, fourth in 2007, third in 2008, second in 2009, and fourth in 2011. EGC swept the New England Championships in the 2009 and 2011 and has won the Gilcreast Bowl (overall team points) in 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2004, 2003, 2002, 1999, 1996, and 1994. Olympians include Anne Marden '76, Rajanya Shah '92, Sabrina Kolker '98, and Andréanne Morin '02. Many Exeter Girls' Crew graduates are recruited to Division 1 collegiate rowing teams and onto various national teams. In the past, many rowers at Exeter have pursued and achieved recognition on the US Junior National Team while still attending Exeter.

In 2012, Exeter Girls' Crew attended Women's Henley Regatta in Henley-on-Thames, England. All races are "dual" races with only two crews competing at a time, but the bracket is single-elimination with no repechage races or petite finals. In the final, Exeter raced against Mount St. Joseph Academy of Flourtown, Pennsylvania. Mount St. Joseph were favored going into the final, having won at the Stotesbury Cup Regatta. In a photo finish, Exeter triumphed by a mere two feet–equivalent to less than one-quarter second. For their victory, Exeter won the Peabody Cup and received memberships into the Vitrix Henley Women's Regatta Winners' Club.[87]

In November 2014, the boys' cross country program won their fourth consecutive NEPSTA title to establish themselves as the team with most consecutive titles in league history.

Student life

Exeter had a gendered dress code until June 2015.[88] Boys were required to wear collared shirts and ties or turtlenecks. Girls were required to wear non-revealing, appropriate attire. Skirts and shorts must reach finger-tip length, and straps may not be less than two fingers wide. Jeans were allowed for boys and girls; however, "hoodies," graphic T-shirts, and athletic wear are not permitted. The new dress code is gender neutral, and no longer requires ties. Dress code is required only in the classroom setting and Assembly.[89]

The academy has over 100 clubs listed. The number of functioning and reputable clubs fluctuates; several of the listed clubs on the website do not hold tables on Club Night. The Exonian is the school's weekly newspaper. It is the oldest continuously-running preparatory school newspaper in the United States, having begun publishing in 1878. Recently, The Exonian began online publication.[90] Other long-established clubs include ESSO, which focuses on social service outreach; and the PEAN, which is the academy's yearbook. Exeter also has the oldest surviving secondary school society, the Golden Branch (founded in 1818), a society for public speaking, inspired by PEA's Rhetorical Society of 1807–1820. Now known as the Daniel Webster Debate Society, these groups served as America's first secondary school organization for oratory and prepared students for the communication skills required for success at Harvard University.[91] The Model UN club has won the "Best Small Delegation" award at HMUN.[92] Exeter's Mock Trial Association, founded by attorney and historian Walter Stahr,[93] has since 2011 claimed seventeen individual titles, five all-around state titles, and a top-ten spot at the National High School Mock Trial Championship.[94]

Close to 80% of students live in the dormitories, with the other 20% commuting from homes within a 30-mile (50 km) radius. Each residence hall has several faculty members and senior student proctors. There are check-in hours of 8:00 pm (for first- and second-year students), 9:00pm (for third years), and 10:00 pm (for seniors) during the weekdays and 11:00 pm on Saturday night.[89]

Religious life on campus is supported by the Religious Services Department, which provides a vintage stone chapel and a full-service ministry for the spiritual needs of students.[95] The chapel was originally built in 1895 and has been updated. It accommodates worship for "twelve religious traditions including Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Hindu, Quaker, Buddhist, Catholic among others"[96] as well as Secular Humanism.[95]

Weekly attendance at the religious service of their choice was required of students until 1969, after which religion at Exeter languished until it was revived by a new approach "as concerned with the religious dimension of all of our lives as it is with the particular religious needs of any one of us." A renovation of Phillips Church, completed in 2002, provided spaces for worship and meditation for students of diverse religious persuasions.[97]

An incident of sexual misconduct that occurred in the basement of the church in late 2015 brought criticism to the school.[98]

Emblems

Academy seal

Exeter has two chief symbols: a seal depicting a river, sun and beehive, incorporating the academy's mottos; and the Lion Rampant. The seal has similarities to that used by Phillips Academy—an emblem designed by Paul Revere—and its imagery is Masonic in nature. A beehive often represented the industry and cooperation of a lodge or, in this case, the studies and united efforts of Academy students. The Lion Rampant is derived from the Phillips family's coat of arms, and suggests that all of the Academy's alumni are part of the "Exonian family".

Exeter has three mottoes on the Academy seal: Non Sibi (Latin 'Not for oneself') indicating a life based on community and duty; Finis origine pendet (Latin 'The end depends on the beginning') reflecting Exeter's emphasis on hard work as preparation for a fruitful adult life; and Χάριτι Θεοῦ (Greek 'By the grace of God') reflecting Exeter's Calvinist origins, of which the only remnant today is the school's requirement that most students take two courses in religion or philosophy.[99]

School colors and the alumnus tie

There are several variants of school colors associated with Phillips Exeter Academy that range from crimson red and white to burgundy red and silver. Black is also a color associated with the school to a lesser extent. The official school colors are lively maroon and gray. The traditional school tie is a burgundy red tie with alternating diagonal silver stripes and silver lions rampant.

Notable alumni

Early alumni of Exeter include US Senator Daniel Webster (1796)[100]; John Adams Dix (1809)[101] a Secretary of the Treasury and Governor of New York; US President Franklin Pierce (1820)[102]; Abraham Lincoln's son and 35th Secretary of War Robert Lincoln (1860)[103]; Ulysses S. Grant, Jr. (1870)[104]; Richard and Francis Cleveland;[105] "grandfather of football" Amos Alonzo Stagg (1880)[106]; Pulitzer Prize-winning author Booth Tarkington (1889)[107] and Hugo W. Koehler (1903), American naval spy during the Russian Revolution and step-father of United States Senator Claiborne Pell.[108] [109] John Knowles, author of A Separate Peace and Peace Breaks Out, was a 1945 graduate; both novels are set at the fictional Devon School, which serves as an analog for his alma mater.[110]

Exeter alumni pursue careers in various fields. Other alumni noted for their work in government include Gifford Pinchot,[111] Lewis Cass,[112] Judd Gregg,[113] Jay Rockefeller,[114] Kent Conrad,[115] John Negroponte,[116] Bobby Shriver,[117] Robert Bauer[118] and Peter Orszag.[119] Alumni notable for their military service include Secretary of Navy George Bancroft,[120] Benjamin Butler,[121] and Charles C. Krulak.[122] Authors George Plimpton,[123] John Knowles,[124] Gore Vidal,[125] John Irving (whose stepfather taught at Exeter),[126] Robert Anderson,[127] Dan Brown (whose father taught at Exeter),[128] Peter Benchley,[129] James Agee,[130] Chang-Rae Lee,[131] Debby Herbenick,[132] Stewart Brand,[133] Norb Vonnegut[134] and Roland Merullo[135] also attended the academy.

Other notable alumni include businessmen Joseph Coors,[136] Michael Lynton,[137] Tom Steyer,[138] and Mark Zuckerberg[139]; lawyer Bradley Palmer[140]; journalists Drew Pearson,[141] Dwight Macdonald,[142] James F. Hoge, Jr.,[143] Paul Klebnikov,[144] Trish Regan,[145] Suzy Welch,[146] and Sarah Lyall[147]; actors Michael Cerveris,[148] Catherine Disher,[149] Jack Gilpin,[150] and Alessandro Nivola[151]; film director Howard Hawks[152]; musicians Bill Keith,[153] Benmont Tench,[154] China Forbes,[155] Ketch Secor,[156] Win Butler[157] and William Butler[158]; historians Robert Cowley,[159] Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.,[160] and Brooks D. Simpson[161]; writers Roxane Gay[162] and Joyce Maynard[163]; screenwriter Tom Whedon[164]; baseball players Robert Rolfe[165] and Sam Fuld[166]; educators Jared Sparks[167] and Benno C. Schmidt, Jr.[168]; composer Adam Guettel[169]; humorist Greg Daniels[170]; mathematicians Shinichi Mochizuki,[171] David Mumford,[172] and Lloyd Shapley, winner of the 2012 Nobel Prize in economics[173]; economist Paul Romer, winner of the 2018 Nobel Prize in economics,[174] computer scientist Adam D'Angelo (co-founder of Quora)[175]; and philosopher and evolutionary biologist Daniel Dennett.[176]

Other academic programs

Summer school

Each summer, Phillips Exeter hosts over 780 students from various schools for a five-week program of academic study. The summer program accommodates a diverse student body typically derived from over 40 different states and 45 foreign countries.[177]

Exeter's summer school is divided into two programs of study: Upper School, which offers a wide variety of classes to students currently enrolled in high school who are entering grades ten through 12 as well as serving postgraduates; and Access Exeter, a program for students entering grades eight and nine, which offers accelerated study in the arts, sciences and writing as well as serving as an introduction to the school itself. Access Exeter curriculum consists of six academic clusters; each cluster consists of three courses organized around a focused central theme. Some of Exeter's summer school programs also give students the opportunity to experience studies outside of Exeter's campus environment, including interactions with other top schools and students, experience with Washington D.C., and travel abroad.[178]

Workshops

The Academy offers a number of workshops and conferences for secondary school educators. These include the Exeter Math Institute; the Exeter Humanities Institute; the Math, Science and Technology Conference; the Exeter Astronomy Conference; and the Shakespeare Conference.[179]

The "On Beyond Exeter" program offers one-week seminars for alumni. Most courses are held at the Academy, but some meet in the locations central to the course's topic.

Historical endeavors

In 1952, Exeter, Andover, Lawrenceville, Harvard, Princeton and Yale published the study General Education in School and College: A Committee Report. The report recommended examinations that would place students after admission to college. This program evolved into the Advanced Placement Program.[180][181]

In 1965 Exeter became the second charter member (after Andover) of the School Year Abroad program.[182] The program allows students to reside and study a foreign language abroad.

In popular culture

Several works are based on Exeter and portray the lives of its students. Many are written by alumni who disguise Exeter's name, but not its character, such as John Knowles and his novel A Separate Peace.

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Brandes, Anne; Little, Ginny (September 13, 2018), Academy Center Honors Female Co-Founders, The Exonian

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Feely, Paul (May 22, 2018). "Rawson named Phillips Exeter interim principal". NH Union Leader. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ the trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. "FACTS 2012~2013" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Trustees Approve $93 Million Budget for 2014-2015 Year". The Exonian. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Financial Report 2017" (PDF).

- ^ "Phillips Exeter Academy Tuition & Fees 2018–2019". Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg attended the most elite boarding school in America". Business Insider. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "Financial Report 2017" (PDF). exeter.edu.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b "Exeter Admits 17% of Applicants". theexonian.com. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- ^ a b "Phillips Exeter Academy College Matriculations, 2015-2017" (PDF). exeter.edu. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Governance at Exeter". Phillips Exeter Academy. Archived from the original on February 24, 2013. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c The Phillips Exeter Academy ; a History by Laurence M. Crosbie. The Academy. 1923.

- ^ a b "Phillips Exeter To Go Coed". The Harvard Crimson. February 28, 1970. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ Email To Alumni from Phillips Exeter Academy.|Received September 14, 2018

- ^ a b c Echols, Edward (1970). "The Phillips Exeter Academy, A Pictorial History". Exeter Press: 49.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Brown, Connie (Summer 2005). "Behind Every Successful Man" (PDF). The Exeter Bulletin. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 5, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, Charles Henry Bell, William B. Morrill, Exeter, N.H., 1883. Books.google.com. 1883. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ New Hampshire: A Guide to the Granite State, Federal Writers Project, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1938. Books.google.com. 1938. ISBN 9781603540285. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ General Catalogue of Officers and Students, 1783–1903, The Phillips Exeter Academy, News-Letter Press, Exeter, 1903. Books.google.com. 1903. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ a b the trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. "Phillips Exeter Academy | Academy Chronology". Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bass ... , Jo Ann F.; et al. (2007). A declaration of readers' rights: renewing our commitment to students. Boston: A & B/Pearson. p. 67. ISBN 978-0205499793.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ^ "Why The Classes At Phillips Exeter Are Different Than At Any Other Private School". Business Insider. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ the trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. "Phillips Exeter Academy |Harkness". Archived from the original on December 20, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rimkunas, Barbara (November 4, 2014). Hidden History of Exeter. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781625852649.

- ^ "Phillips Exeter Academy – Academy Chronology". Archived from the original on June 17, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Heskel, Julia; Dyer, Davis (2008). After the Harkness gift : a history of Phillips Exeter Academy since 1930. Exeter, N.H.: Phillips Exeter Academy. ISBN 0976978717.

- ^ Laneri, Raquel. "No. 6: Phillips Exeter Academy". Forbes. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Phillips Exeter Academy – Academics". Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ the trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. "Courses of Instruction". Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ Crosbie, Michael J. (2004). Architecture for science. Mulgrave, Vic.: Images Publ. p. 192. ISBN 1-920744-64-9.

- ^ St. Paul's School. "St. Paul's School ~ Our Academic Program". Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ Harkness Institute. "We learn by doing!". Harknessinstitute.org. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ Now and Then. Repr. San Francisco: Harper SanFrancisco, 1991. p. 47

- ^ "Michael Golay". Simon & Schuster. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Todd Hearon". Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation. April 9, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Berwick Academy to host poet, author Willie Perdomo". fosters.com. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Brief Biography of Zuming Feng from the University of Texas at Dallas". Metroplexmathcircle.wordpress.com. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ "Gwynneth Coogan '83". Phillips Exeter Academy. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Salem's Rep. Garcia named Republican rising star | New Hampshire Salem Observer". Unionleader.com. August 17, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ "Former Olympian Toyin Augustus has raced through life nicely since Beijing". AL.com. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Exeter Principal R.W. Day Resigns For New Career" (PDF). The Phillipian. May 31, 1973.

- ^ "A Capitol Experience". Phillips Exeter Academy. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Selden, Nathan R. W. Selden; Nathan; 16; Academy, a senior at Phillips Exeter; office, this year participated in its Washington intern program in the (June 7, 1981). "PERSONAL GLIMPSES OF WASHINGTON". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

{{cite news}}:|last2=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Phillips Exeter Academy. "2017–2018 Courses of Instruction" (PDF).

- ^ "School History". The Mountain School. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ "School Year Abroad – History". Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Schools - School Year Abroad". www.sya.org. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "College Matriculation for Classes 2015-2017" (PDF). Exeter.edu. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- ^ the trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. "Phillips Exeter Academy | Diversity Programs". Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ the trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. "Fall Bulletin 2001". Archived from the original on March 12, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cunningham, Frank Herbert (1883). Familiar Sketches of the Phillips Exeter Academy and Surroundings. J. R. Osgood.

- ^ Phillips, John. "The Original Deed of Gift from John Phillips to Phillips Exeter Academy, Containing the Constitution, May 17, 1781" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 3, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Boston Globe, Nov. 1998.

- ^ "Who We Are | Phillips Exeter Academy". Exeter.edu. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ "Phillips Exeter Academy Facts 2016–2017" (PDF). Exeter.edu. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- ^ "Phillips Exeter Academy Facts 2017–2018" (PDF).

- ^ the trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. "FACTS 2012~2013" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Lexicon of Exeter Terminology and Slang" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Phillips Exeter Academy | Tuition and Fees". Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ the trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. "Phillips Exeter Academy | Tuition and Financial Aid". Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Julia Dean, "Economy Strains Exeter Financial Aid Budget", The Phillipian, April 24, 2009 in CXXXII no. 9 [1] Archived April 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Phillips Exeter Academy | Tuition and Fees". Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- ^ Strom, Stephanie (August 3, 2007). "Ex-Wall St. Executives Go to Bat to Help Nonprofits". Nytimes.com. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- ^ "KS AR 2004-PDF prep 01.indd" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Fabrikant, Geraldine (January 26, 2008). "At Elite Prep Schools, College-Size Endowments". The New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c d e Aten, Carol Walker (2003). Postcards from Exeter. Portsmouth, NH: Arcadia. p. 45. ISBN 0-7385-3481-1.

- ^ "Rooms with a View – A Portfolio of Exeter Classrooms" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 9, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hartman, Halie. "The 35 Most Amazing Libraries in the World – The Best Colleges". Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ Huxtable, Ada Louise (2008). On architecture: collected reflections on a century of change (1st U.S. ed.). New York: Walker. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-8027-1707-8.

- ^ "Community Hubs". Phillips Exeter Academy. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ "Goel Center for Theater and Dance". Phillips Exeter Academy. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ Centerbrook Architects and Planners. "Centerbrook Architects and Planners > Complete List of Awards". Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ "Tour". Exeter.edu. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tour". Exeter.edu. Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fowler, Glenn (July 27, 1991). "George H. Love, 90, Industrialist Who Headed Two Corporations". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ^ "Phillips Exeter Academy George H. Love'18 Athletic Facility, Exeter by Kallmann McKinnell & Wood Architects". www.kmwarch.com. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ^ "New field house opens at Exeter | Phillips Exeter Academy". exeter.edu. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ^ "Athletic Field House | Phillips Exeter Academy". www.exeter.edu. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ the trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. "Phillips Exeter Academy | Athletic Facilities". Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ New Hampshire: A Guide to the Granite State, Federal Writers' Project, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1938. Books.google.com. 1938. ISBN 9781603540285. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ "Academy Chronology". Phillips Exeter Academy. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Phillips Exeter Academy | Go Big Red!". Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Sam Fuld: Profile". GoStanford.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Montville named Gatorade player of the year". Foster's Daily Democrat. May 30, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ^ Chris Curtis (April 12, 2001). "Freshman is a Perfect Fit; A Closer Look at Sam Fuld". Gostanford.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Race Results Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 8, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Exeter girls win Junior 8+ at Henley Women's Regatta | Exeter Crew". Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ The Exonian 2015-05-14. "Gender-Neutral Dress Code a First for PEA".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Phillips Exeter Academy. "The E Book 2012–2013" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 24, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Exonian". theexonian.com.

- ^ (Echols 1970, p. 21)

- ^ Phillips Exeter Academy. "The Exonian". Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ "About Us". PEA Mock Trial. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ "The Exonian 9 June 2013 — The Exonian Archives". archive.theexonian.com. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "Phillips Church," Phillips Exeter Academy, 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ "Phillips Church at Phillips Exeter Academy: Exeter, NH," Cram and Ferguson Architects. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Mark. "At Phillips Exeter, a World of Religious Diversity," The New York Times, 11 April 2014. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Abelson, Jenn, "Phillips Exeter Academy under fire again for its handling of sexual misconduct allegations," The Boston Globe, 13 July 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ the Trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. "Phillips Exeter Academy | Academy Archives". Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ "WEBSTER, Daniel, (1782 - 1852)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ Dix, Morgan (1883). Memoirs of John Adams Dix. Harper & Brothers.

- ^ "Franklin Pierce". Totally History. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ "Whatever happened to Robert Todd Lincoln?". seacoastonline.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Wead, Doug (January 6, 2004). All the Presidents' Children: Triumph and Tragedy in the Lives of America's First Families. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743446334.

- ^ New Hampshire: A Guide to the Granite State, Federal Writers' Project, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1938. Books.google.com. 1938. ISBN 9781603540285. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ "STAGG AT EXETER DINNER.; Football Coach Tells Academy Alumni of His Student Days". The New York Times. December 16, 1932.

- ^ "HOOSIER BEACON: Booth Tarkington, Hoosier novelist". Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ General Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the Phillips Exeter Academy, 1903, p. 186

- ^ Secretary's Fourth Report, Harvard College, Class of 1907

- ^ Magrone, Callie. "Author John Knowles dies". seacoastonline.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Gifford Pinchot (1865–1946)". United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service. 2018.

- ^ Phillips Exeter Academy (1903). General Catalogue of Officers and Students, 1783-1903. Phillips Exeter Academy. p. 75.

- ^ Altman, Alex (February 4, 2009). "Commerce Secretary Judd Gregg". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Toner, Robin. "Rockefeller's Assets". Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Nick. "Conrad's early career marked by 1986 win, pledge". Bismarck Tribune. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Blumenfeld, Laura (January 29, 2007). "For Negroponte, Move to State Dept. Is a Homecoming". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Jerry (September 22, 2015). RFK Jr.: Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and the Dark Side of the Dream. Macmillan. ISBN 9781250032959.

- ^ "Bob Bauer". Washington Post. July 26, 2012. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Obama expected to name Peter Orszag OMB director (11/18/08)". GovExec.com. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "George Bancroft". Wikipedia. October 13, 2017.

- ^ West, Richard Sedgewick (1965). Lincoln's Scapegoat General: A Life of Benjamin F. Butler, 1818–1893. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- ^ "Charles C. Krulak :: Notable Graduates :: USNA". www.usna.edu. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Remnick, David (September 29, 2003). "George Plimpton". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Magrone, Callie. "Author John Knowles dies". seacoastonline.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Gore Vidal: A Critical Companion Susan Baker, Curtis S. Gibson. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997. ISBN 0-313-29579-4. p. 3.

- ^ "Becoming John Irving". unhmagazine.unh.edu. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Weber, Bruce (February 10, 2009). "Robert Anderson, Playwright of 'Tea and Sympathy,' Dies at 91". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Rothman, Joshua (June 21, 2013). "When Dan Brown Came to Visit". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Nathaniel Benchley". HarperCollins US. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Agee FIlms: Agee Chronology". www.ageefilms.org. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Wu, Yung-Hsing. "Chang-rae Lee." Asian- American Writers. Ed. Deborah L. Madsen. Detroit: Gale, 2005. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 312. Literature Resource Center. Web. 19 Apr. 2014.

- ^ "How We Educate Students". Phillips Exeter Academy. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Bio..." sb.longnow.org. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Book tour for best-selling author, Norb Vonnegut » Newman Communications". newmancom.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "About". rolandmerullo.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Joe Coors Jr., former black sheep of family, now running for office". The Denver Post. September 22, 2012. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Robert Boynton". www.robertboynton.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Tom Steyer: An Inconvenient Billionaire". Men's Journal. February 18, 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Vargas, Jose Antonio. "The Face of Facenook; Mark Zuckerberg Opens Up", The New Yorker, September 20, 2010. Accessed March 21, 2017. "According to his Facebook profile, Zuckerberg has three sisters (Randi, Donna, and Arielle), all of whom he’s friends with. He’s friends with his parents, Karen and Edward Zuckerberg. He graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy and attended Harvard University."

- ^ tritown@wickedlocal.com, Alison D'Amaro. "'Bradley Palmer, The Man Himself' tour on Friday mornings in Topsfield". Tri. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Drew Pearson Papers An inventory of his papers at Syracuse University". library.syr.edu. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "From Trotsky to Midcult: In Search of Dwight Macdonald". Observer. March 27, 2006. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Jim Hoge". IMDb. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Wheeler, Carolynne; Reed, Christopher (July 15, 2004). "Obituary: Paul Klebnikov". the Guardian. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Tara. "PEA hosts graduate and CNBC's Trish Regan". seacoastonline.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "New Wife, New Life". PEOPLE.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (August 24, 2009). The Anglo Files: A Field Guide to the British. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393334760.

- ^ "Michael Cerveris | The Official Masterworks Broadway Site". The Official Masterworks Broadway Site. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Catherine Disher". IMDb. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Actor turns from casting calls to a higher calling | Archives". archives.rep-am.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Huck, Peter (July 13, 2001). "Charmer chameleon". ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (December 28, 1977). "Hollywood Director Howard Hawks Dies". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Friskics-Warren, Bill (October 26, 2015). "Bill Keith, Who Uncovered Banjo's Melodic Potential, Dies at 75". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Petty and the Heartbreakers' love affair with Boston has lasted forever - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "The Exeter Bulletin Online". March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "How Ketch Secor Started Wild Roots Band Old Crow Medicine Show". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Intelligencer: September 26 - October 3, 2005". NYMag.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "All Fired Up: Northwestern Magazine - Northwestern University". www.northwestern.edu. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ "Edith P. Lorillard Wed to Robert Cowley". The New York Times. June 25, 1978. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (March 1, 2007). "Arthur Schlesinger, Historian of Power, Dies at 89". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "The Exeter Bulletin, winter 2012". Issuu. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ John Freeman (Summer 2014). "Roxane Gay". Bomb. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Joyce Maynard Bounces Back With Another Chapter". tribunedigital-chicagotribune. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Pascale, Amy (August 1, 2014). Joss Whedon: The Biography. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 9781613741047.

- ^ "Red Rolfe | Society for American Baseball Research". sabr.org. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Super Sam - Sam Fuld - New Hampshire Magazine - July 2011". www.nhmagazine.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Adams, Herbert Baxter (1970). The Life and Writings of Jared Sparks: Comprising Selections from His Journals and Correspondence. Books for Libraries Press.

- ^ "YALE SAID TO PICK BENNO SCHMIDT AS PRESIDENT". Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Guettel, Adam | Grove Music". doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002284517. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Exeter Explorations: Bringing New Perspectives Back to Campus". Phillips Exeter Academy. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "The Paradox of the Proof". Project Wordsworth. May 5, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "The Shaw Prize - Top prizes for astronomy, life science and mathematics". www.shawprize.org. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ INFORMS. "Shapley, Lloyd S." INFORMS. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "2 Researchers With MIT Ties Win Nobel Prize For Economics". October 8, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

{{cite news}}: no-break space character in|title=at position 48 (help) - ^ "Adam D'Angelo". Forbes. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "The secret of consciousness, with Daniel C. Dennett | New Philosopher". www.newphilosopher.com. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ the Trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. "Phillips Exeter Academy | Summer School". Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ the Trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. "Phillips Exeter Academy | Academic Programs". Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Summer Programs". Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Stanley N. Katz. "The Liberal Arts in School and College". Chronicle.com. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Advanced Placement Program" (PDF). Collegeboard.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "A Brief History: Where did we come from?". Sya.org. Archived from the original on July 28, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- Paul Monroe, ed. (1913), "Phillips Academy, Exeter, N.H.", Cyclopedia of Education, vol. 4, New York: Macmillan – via HathiTrust

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

External links

- Ten Schools Admissions Organization

- Phillips Exeter Academy

- Boarding schools in New Hampshire

- Private high schools in New Hampshire

- Preparatory schools in New Hampshire

- Educational institutions established in the 1780s

- 1781 establishments in New Hampshire

- Co-educational boarding schools

- Schools in Rockingham County, New Hampshire

- Exeter, New Hampshire

- Six Schools League

- Phillips family (New England)