Springfield, Missouri

Springfield, Missouri | |

|---|---|

The Hammons Tower as seen from Jordan Valley Park | |

| Nickname(s): The "Queen City of the Ozarks" "Birthplace of Route 66" | |

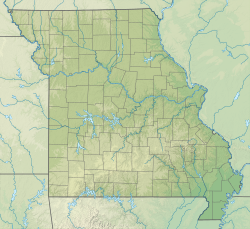

Location in the state of Missouri | |

| Coordinates: 37°12′55″N 93°17′54″W / 37.21528°N 93.29833°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Missouri |

| Counties | Greene, Christian |

| Founded | 1835 |

| Incorporated | 1838 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-manager |

| • Mayor | Ken McClure |

| Area | |

| • City | 82.31 sq mi (213.18 km2) |

| • Land | 81.72 sq mi (211.65 km2) |

| • Water | 0.59 sq mi (1.53 km2) |

| • Metro | 3,021 sq mi (7,824 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,299 ft (396 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 159,498 |

| • Estimate (2017)[4] | 167,376 |

| • Rank | US: 152nd |

| • Density | 1,900/sq mi (750/km2) |

| • Urban | 273,724 (US: 138th) |

| • Metro | 541,991 (US: 101st) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 65800-65899 |

| Area code | 417 |

| FIPS code | 29-70000 |

| Website | www.springfieldmo.gov |

Springfield is the third-largest city in the state of Missouri and the county seat of Greene County.[5] As of the 2010 census, its population was 159,498. As of 2017, the Census Bureau estimated its population at 167,376. It is one of the two principal cities of the Springfield-Branson Metropolitan Area, which has a population of 541,991 and includes the counties of Christian, Dallas, Greene, Polk, Webster, Stone and Taney.

Springfield's nickname is "Queen City of the Ozarks" and it is known as the "Birthplace of Route 66". It is home to three universities, Missouri State University, Drury University, and Evangel University.

History

The origin of the city's name is unclear, but the most common view is that it was named for Springfield, Massachusetts by migrants from that area. One account holds that James Wilson, who lived in the then unnamed city, offered free whiskey to anyone who would vote for the name Springfield, after his hometown in Massachusetts.[6]

The editor of the Springfield Express, J. G. Newbill, said in the November 11, 1881 issue:

"It has been stated that this city got its name from the fact of a spring and field being near by just west of town. But such is not a correct version. When the authorized persons met and adopted the title of the "Future Great" of the Southwest, several of the earliest settlers had handed in their favorite names, among whom was Kindred Rose, who presented the winning name, "Springfield," in honor of his former home town, Springfield, Tennessee."[7]

In 1883, historian R. I. Holcombe wrote:

"The town took its name from the circumstance of there being a spring under the hill, on the creek, while on top of the hill, where the principal portion of the town lay, there was a field."[7]

Early settlement

The presence of the Native Americans in the area slowed the European-American settlement of the land.[8] Long before the 1830s, the native Kickapoo and Osage, and the Lenape (Delaware) from the mid-Atlantic coast had settled in this general area. The Osage had been the dominant tribe for more than a century in the larger region.

On the southeastern side of the city in 1812, about 500 Kickapoo Native Americans built a small village of about 100 wigwams. They abandoned the site in 1828. Ten miles south of the site of Springfield, the Lenape had built a substantial dwelling of houses that borrowed elements of Anglo colonial style from the mid-Atlantic, where their people had migrated from.[7]

The first European-American settlers to the area were John Polk Campbell and his brother, who moved to the area in 1829 from Tennessee. Campbell chose the area because of the presence of a natural well that flowed into a small stream. He staked his claim by carving his initials in a tree.[8] Cambell was joined by settlers Thomas Finney, Samuel Weaver, and Joseph Miller. They proceeded to clear the land of trees to develop it for farms. A small general store was soon opened.[7]

In 1833, the southern part of the state was named Greene County after Revolutionary War hero General Nathanael Greene.[8] The legislature deeded 50 acres of land to John Campbell for the creation of a county seat in 1835. Campbell laid out city streets and lots.[9] The town was incorporated in 1838.[10] In 1878, the town got its nickname the "Queen City of the Ozarks."[8]

The United States government enforced Indian Removal during the 1830s, forcing land cessions in the Southeast and other areas, and relocating tribes to Indian Territory, which later developed as Oklahoma. During the 1838 relocation of Cherokee natives, the Trail of Tears passed through Springfield to the west, along the Old Wire Road.[11][12]

Civil War

By 1861, Springfield's population had grown to approximately 2,000, and it had become an important commercial hub. At the start of the American Civil War, Springfield was divided in its loyalty, as it had been settled by people from both the North and South, as well as by German immigrants in the mid-19th century who tended to support the Union.

The Union and Confederate armies both recognized the city's strategic importance and sought to control it. They fought the Battle of Wilson's Creek on August 10, 1861, a few miles southwest of town.[7] The battle was a Confederate victory, and Nathaniel Lyon became the first Union General killed in Civil War. Union troops retreated to Lebanon to regroup. When they returned, they found that most of the Confederate army had withdrawn.[12]

On October 25, 1861, Union Major Charles Zagonyi led an attack against the remaining Confederates in the area, in a battle known as the First Battle of Springfield, or Zagonyi's Charge. Zagonyi's men removed the Confederate flag from Springfield's public square and returned to camp. It was the only Union victory in southwestern Missouri in 1861.[13] The increased military activity in the area set the stage for the Battle of Pea Ridge in northern Arkansas in March 1862.[12]

On January 8, 1863, Confederate forces under General John S. Marmaduke advanced to take control of Springfield and an urban fight ensued. But that evening, the Confederates withdrew. This became known as the Second Battle of Springfield. Marmaduke sent a message to the Union forces asking that the Confederate casualties have a proper burial. The city remained under Union control for the remainder of the war.[12] The US army used Springfield as a supply base and central point of operation for military activities in the area.[7]

"Wild" Bill Hickok

Promptly after the Civil War ended on July 21, 1865 Wild Bill Hickok shot and killed Davis Tutt in a shootout over a disagreement about a debt Tutt claimed Hickok owed him. During a poker game at the former Lyon House Hotel, in response to the disagreement over the amount, Tutt had taken Hickok's watch, which Hickok demanded he return immediately. Hickok warned that Tutt had better not be seen wearing that watch, then spotted him wearing it in Park Central Square, prompting the gunfight.

On January 25, 1866, Hickok was still in Springfield when he witnessed a Springfield police officer, John Orr, shoot and kill James Coleman after Coleman interfered with the arrest of Coleman's friend Bingham, who was drunk and disorderly. Hickok provided testimony in the case. Orr was arrested, released on bail, and immediately fled the country. He was never brought to trial or heard from again.[14]

Lynchings

The period after Reconstruction and into the early 20th century continued to be socially volatile, with whites attacking blacks in the South in order to help maintain white supremacy. Some cities and counties in Missouri, particularly in former slaveholding areas, also had lynchings of freedmen and their descendants.

On April 14, 1906, a white mob broke into the Springfield county jail, and lynched two black men, Horace Duncan and Fred Coker, for allegedly sexually assaulting Mina Edwards, a white woman. Later they returned to the jail, where other African-American prisoners were being held, and pulled out Will Allen, who had been accused of murdering a white man. All three suspects were hanged from the Gottfried Tower, which held a replica of the Statue of Liberty, and burned in the courthouse square by a mob of more than 2,000 whites. Judge Azariah W. Lincoln called for a grand jury, but no one was prosecuted. The proceedings were covered by national newspapers, the New York Times and Los Angeles Times. In the immediate aftermath, local Missouri people reportedly issued two commemorative coins.[15]

Duncan's and Coker's employer testified that they were at his business at the time of the crime against Edwards, and other evidence suggested that they and Allen were all innocent.[15][16] These three are the only recorded lynchings in Greene County.[17] But the extrajudicial murders were part of a pattern of discrimination, repeated violence and intimidation of African Americans in this city and southwest Missouri from 1894 to 1909, in an attempt to expel them from the region.[18] Whites in Lawrence County also lynched three African-American men in this period.[17] After the mass lynching in Springfield, many African Americans left the area in a large exodus.[18]

In the 21st century, African Americans constitute a very small minority in Springfield and throughout the Ozarks. A historic plaque on the southeast corner of the Springfield courthouse square commemorates Duncan, Coker, and Allen, the three victims of mob violence.[15][19]

Geography

Springfield is on the Springfield Plateau of the Ozarks region of southwest Missouri. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 82.31 square miles (213.2 square kilometres), of which 81.72 square miles (211.7 square kilometres) is land and 0.59 square miles (1.5 square kilometres) (0.7%) is water.[2]

The city of Springfield is mainly flat with rolling hills and cliffs surrounding its south, east, and north sections. Springfield is on the Springfield Plateau, which reaches from Northwest Arkansas to Central Missouri. Most of the plateau is characterized by forest, pastures and shrub-scrub habitats.[20] Many streams and tributaries, such as the James River, Galloway Creek and Jordan Creek, flow within or near the city. Nearby lakes include Table Rock Lake, Stockton Lake, McDaniel Lake, Fellows Lake, Lake Springfield, and Pomme de Terre Lake. Springfield is near the population center of the United States, about 80 miles (130 km) to the east.

Climate

Springfield has an average surface wind velocity comparable to Chicago's, according to information compiled at the National Climatic Data Center at NOAA.[21] It is placed within "Power Class 3" in the Wind Energy Resource Atlas published by a branch of the U.S. Department of Energy; having an average wind speed range of 6.4 to 7.0 miles per hour.[22]

Springfield lies in the northern limits of a humid subtropical climate (Cfa), as defined by the Köppen climate classification system. As such, it experiences times of exceptional humidity; especially in late summer.[23] The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 32.6 °F (0.3 °C) in January to 78.2 °F (25.7 °C) in July. On average, there are 39 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs, 2.0 days of 100 °F (38 °C)+ highs, 16 days where the high fails to rise above freezing, and 2.5 nights of lows at or below 0 °F (−18 °C) per year.[24] It has an average annual precipitation of 45.6 inches (1,160 mm), including an average 17.0 inches (43 cm) of snow. Extremes in temperature range from −29 °F (−34 °C) on February 12, 1899 up to 113 °F (45 °C) on July 14, 1954.

According to a 2007 story in Forbes magazine's list of "America's Wildest Weather Cities" and the Weather Variety Index, Springfield is the city with the most varied weather in the United States. On May 1, 2013, Springfield reached a high temperature of 81 degrees Fahrenheit. By the evening of May 2, snow was falling, persisting into the following day and eventually accumulating to about two inches.[25][26]

| Climate data for Springfield–Branson National Airport, Missouri (1991−2020 normals,[a] extremes 1888−present[b]) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 76 (24) |

84 (29) |

92 (33) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

101 (38) |

113 (45) |

108 (42) |

104 (40) |

93 (34) |

83 (28) |

77 (25) |

113 (45) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 66.8 (19.3) |

72.0 (22.2) |

78.9 (26.1) |

83.5 (28.6) |

87.4 (30.8) |

92.5 (33.6) |

96.8 (36.0) |

98.2 (36.8) |

92.6 (33.7) |

85.0 (29.4) |

74.7 (23.7) |

67.4 (19.7) |

99.1 (37.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 44.3 (6.8) |

49.5 (9.7) |

58.9 (14.9) |

68.4 (20.2) |

76.3 (24.6) |

85.2 (29.6) |

89.6 (32.0) |

89.1 (31.7) |

81.4 (27.4) |

69.9 (21.1) |

57.3 (14.1) |

47.0 (8.3) |

68.1 (20.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 34.3 (1.3) |

38.7 (3.7) |

47.6 (8.7) |

57.0 (13.9) |

66.0 (18.9) |

74.9 (23.8) |

79.2 (26.2) |

78.2 (25.7) |

70.3 (21.3) |

58.6 (14.8) |

46.7 (8.2) |

37.4 (3.0) |

57.4 (14.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 24.2 (−4.3) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

36.2 (2.3) |

45.6 (7.6) |

55.6 (13.1) |

64.6 (18.1) |

68.8 (20.4) |

67.3 (19.6) |

59.1 (15.1) |

47.3 (8.5) |

36.2 (2.3) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

46.7 (8.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 3.5 (−15.8) |

8.4 (−13.1) |

15.9 (−8.9) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

38.9 (3.8) |

51.8 (11.0) |

58.3 (14.6) |

55.5 (13.1) |

42.7 (5.9) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

18.1 (−7.7) |

8.1 (−13.3) |

−1.0 (−18.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −19 (−28) |

−29 (−34) |

−8 (−22) |

16 (−9) |

29 (−2) |

42 (6) |

44 (7) |

44 (7) |

30 (−1) |

18 (−8) |

4 (−16) |

−16 (−27) |

−29 (−34) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.54 (65) |

2.40 (61) |

3.51 (89) |

4.71 (120) |

5.56 (141) |

4.47 (114) |

3.85 (98) |

3.59 (91) |

4.31 (109) |

3.60 (91) |

3.56 (90) |

2.61 (66) |

44.71 (1,136) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.4 (11) |

3.3 (8.4) |

2.0 (5.1) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.6 (1.5) |

3.3 (8.4) |

13.7 (35) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.1 | 7.7 | 10.7 | 10.8 | 12.4 | 10.2 | 8.8 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 9.0 | 8.6 | 8.0 | 110.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.4 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 10.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68.3 | 68.5 | 65.2 | 64.5 | 70.7 | 72.3 | 70.4 | 69.5 | 72.9 | 68.2 | 69.6 | 70.9 | 69.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 20.8 (−6.2) |

25.0 (−3.9) |

33.1 (0.6) |

43.0 (6.1) |

53.8 (12.1) |

62.4 (16.9) |

65.8 (18.8) |

63.9 (17.7) |

58.1 (14.5) |

45.3 (7.4) |

35.1 (1.7) |

25.5 (−3.6) |

44.3 (6.8) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 167.6 | 157.4 | 208.7 | 236.4 | 268.0 | 282.7 | 321.6 | 292.1 | 237.6 | 217.3 | 155.1 | 145.9 | 2,690.4 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 54 | 52 | 56 | 60 | 61 | 64 | 72 | 70 | 64 | 62 | 51 | 49 | 60 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point, and sun 1961−1990)[27][28][29] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 415 | — | |

| 1860 | 1,235 | 197.6% | |

| 1870 | 5,555 | 349.8% | |

| 1880 | 6,522 | 17.4% | |

| 1890 | 21,850 | 235.0% | |

| 1900 | 23,267 | 6.5% | |

| 1910 | 35,201 | 51.3% | |

| 1920 | 39,631 | 12.6% | |

| 1930 | 57,527 | 45.2% | |

| 1940 | 61,238 | 6.5% | |

| 1950 | 66,731 | 9.0% | |

| 1960 | 95,865 | 43.7% | |

| 1970 | 120,096 | 25.3% | |

| 1980 | 133,116 | 10.8% | |

| 1990 | 140,494 | 5.5% | |

| 2000 | 151,580 | 7.9% | |

| 2010 | 159,498 | 5.2% | |

| 2017 (est.) | 167,376 | [4] | 4.9% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[30] 2017 Estimate[4] | |||

2010 census

As of the 2010 census,[3] there were 159,498 people, 69,754 households, and 35,453 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,951.8 inhabitants per square mile (753.6/km2). There were 77,620 housing units at an average density of 949.8 per square mile (366.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 88.7% White, 4.1% African American, 0.8% Native American, 1.9% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 1.2% from other races, and 3.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.7% of the population.

There were 69,754 households of which 23.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 34.4% were married couples living together, 11.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.7% had a male householder with no wife present, and 49.2% were non-families. 37.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.13 and the average family size was 2.81.

The median age in the city was 33.2 years. 18.3% of residents were under the age of 18; 18.4% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26% were from 25 to 44; 22.7% were from 45 to 64; and 14.5% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.5% male and 51.5% female.

2000 census

According to the 2000 United States Census,[31] 151,580 people, 64,691 households, and 35,709 families resided in the city. The population density was 2,072.0 people per square mile (800.0/km2). There were 69,650 housing units at an average density of 952.1/mi2 (367.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 91.69% White, 3.27% African American, 0.75% Native American, 1.36% Asian, 0.09% Pacific Islander, 0.88% from other races, and 1.95% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.31% of the population.

There were 64,691 households out of which 24.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.7% were married couples living together, 10.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 44.8% were non-families. 35.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.17 and the average family size was 2.82. In the city 19.9% were under the age of 18, 17.4% from 18 to 24, 28.0% from 25 to 44, 19.8% from 45 to 64, and 14.9% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $29,563, and the median income for a family was $38,114. Males had a median income of $27,778 versus $20,980 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,711. About 9.9% of families and 15.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.1% of those under age 18 and 7.9% of those age 65 or over.

Neighborhoods

Registered

Registered neighborhoods include:[32] Bissett, Bradford Park, Doling, Grant Beach, Heart of the Westside, Midtown, Oak Grove, Parkcrest, Phelps Grove, Robberson, Rountree, Tom Watkins, Weller, West Central, Westside Community Betterment, and Woodland Heights

Affiliated neighborhood groups

Affiliated neighborhood groups unregistered with the city include:[32]

- Cinnamon On The Hill

- Cinnamon Square

- Cooper Estates

- Fox Grape

- Kay Pointe

- Kingsbury Forest

- Lakewood Village

- Mission Hills

- National Place

- Parkwest Village

- Parkwood Survival

- Quail Creek

- Ravenwood South

- Sherman Ave Project Area

- Spring Creek

- Coachlight

Economy

Springfield's economy is based on health care, manufacturing, retail, education, and tourism.[33] With a Gross Metropolitan Product of $13.66 billion in 2004 and $18.6 billion in 2016 according to missourieconomy.org. Springfield's economy makes up 6.7% of the Gross State Product of Missouri.[34]

Total retail sales exceed $4.1 billion annually in Springfield and $5.8 billion in the Springfield MSA. Its largest shopping mall is Battlefield Mall. According to the Springfield Convention & Visitors Bureau, an estimated 3,000,000 overnight visitors and day-trippers annually visit the city. The city has more than 60 lodging facilities and 6,000 hotel rooms. The Convention & Visitors Bureau spends more than $1,000,000 annually marketing the city as a travel destination.

Positronic, Bass Pro Shops, John Q. Hammons Hotels & Resorts, BKD, Noble & Associates, Prime, Inc., Springfield ReManufacturing, and O'Reilly Auto Parts have their national headquarters in Springfield.[35] In addition, two major American Christian denominations—General Council of the Assemblies of God in the United States of America (one of the largest of the Pentecostal denominations) and Baptist Bible Fellowship International (a fundamentalist Baptist denomination founded by J. Frank Norris)—are headquartered in the city.

Top employers

According to the Springfield Area Chamber of Commerce,[36] the top 2014 employers in the metro area are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mercy Health System | 9,004 |

| 2 | CoxHealth | 7,891 |

| 3 | Wal-Mart | 3,567 |

| 4 | Springfield Public Schools | 3,206 |

| 5 | Missouri State University | 2,583 |

| 6 | Bass Pro Shops/Tracker Marine | 2,557 |

| 7 | United States Government | 2,400 |

| 8 | State of Missouri | 2,326 |

| 9 | Citizens Memorial Healthcare | 1,900 |

| 10 | City of Springfield | 1,607 |

| 11 | O'Reilly Auto Parts | 1,458 |

| 12 | Chase Card Services | 1,397 |

Government

Springfield city government is based on the council-manager system. By charter, the city has eight council members, each elected for a four-year term on a nonpartisan basis, and a mayor elected for a two-year term. The mayor is Ken McClure. Council members include Phyllis Ferguson (Zone 1), Dr. Thomas Prater (Zone 2), Mike Schilling (Zone 3), Matt Simpson (Zone 4), Jan Fisk (General A), Craig Hosmer (General B), Kristi Fulnecky (General C) and Richard Ollis (General D). Greg Burris, the city manager, appointed by the council to be the city's chief executive and administrative officer, enforces the laws as required by the city charter. The presiding officer at council meetings is the mayor. Council meetings are held every other Monday night in City Council Chambers. City council elections are held the first Tuesday in April.

City Utilities of Springfield (CU) is a city-owned utility serving the Springfield area with electricity, natural gas, water, telecommunications and transit services. CU provides service to over 106,000 customers.

Education

The Springfield Public School District is the largest district in the state of Missouri with an official fall 2011 enrollment of 24,366 students attending 50 schools.[37] Public high schools include Central High School, Kickapoo High School, Hillcrest High School, Parkview High School, and Glendale High School. Private high schools include Springfield Sudbury School, Summit Preparatory School, Greenwood Laboratory School, New Covenant Academy, Springfield Lutheran School, Springfield Catholic High School, Christian Schools of Springfield, and Grace Classical Academy.

Springfield has several colleges and universities. Founded in 1905 as the Fourth District Normal School, Missouri State University (MSU) is the state's second largest university by enrollment, with over 26,000 students.[38] For the seventh consecutive year, MSU was selected for The Princeton Review's 2010 list of "Best Colleges: Region by Region." Drury University is a private university with nearly 5,000 students[39] and consistently ranks in U.S. News & World Report's Top 10 Universities in the Midwest.[40] Ozarks Technical Community College (OTC) is the second largest college in the city of Springfield, having more than 15,000 students in attendance.[41] MSU, Drury, and OTC are all located in and around downtown Springfield.

Other colleges in Springfield include Baptist Bible College, Evangel University and Assemblies of God Theological Seminary, and Cox College (Nursing and Allied Health). Branch campuses in Springfield include Mercy College of Nursing and Health Sciences of Southwest Baptist University,[42] Everest College, Columbia College, Webster University, and University of Phoenix. In 2013, a consolidation of Central Bible College, the Assemblies of God Theological Seminary, and Evangel University occurred and is now known as Evangel University.

Parks and recreation

The Springfield-Greene County Park Board manages 3,200 acres and 103 sites,[43] including the Nathanael Greene/Close Memorial Park, which contains the historic Gray-Campbell Farmstead, Mizumoto Japanese Stroll Garden, Master Gardener demonstration gardens, Dr. Bill Roston Native Butterfly House, and Springfield-Greene County Botanical Center;[44] the Rutledge-Wilson Farm Community Park; the Mediacom Ice Park; the Cooper Park and Sports Complex; the Dickerson Park Zoo; and various other public parks, community centers, and facilities.[45]

The non-profit Ozark Greenways Inc. promotes trail recreation and local bicycling through the establishment of greenway trails, including a 35-mile crushed-gravel trail, the Frisco Highline Trail connecting Springfield to the town of Bolivar, and smaller trails connecting parks and sites of interest within the town and county.[46]

The Missouri Department of Conservation operates the Springfield Nature Center and numerous nearby conservation areas.[47]

The National Park Service operates the nearby Wilson's Creek National Battlefield.[48]

Springfield's metropolitan area is reasonably well-developed, but situated within close distance of recreational lakes, waterways, caves, and forests, such as the James River, Busiek State Forest, Lake Springfield, Table Rock Lake, Buffalo National River, Ozark National Scenic Riverways, and Fantastic Caverns.

Sports

Springfield plays host to college teams from Missouri State University (NCAA Division I), Drury University (NCAA Division II), Evangel University (NAIA) and few minor professional teams (see below). The Springfield Cardinals, the Double-A affiliate of the St. Louis Cardinals, have played at Hammons Field in downtown Springfield since their inaugural season in 2005. Springfield is also home to a number of amateur sporting events. The PGA sponsored Price Cutter Charity Championship is played at Highland Springs Country Club on the southeast side of Springfield. The Missouri Sports Hall of Fame is located near the city as well. JQH Arena (capacity 11,000) opened in 2008 and is home to the Missouri State University Bears and Lady Bears basketball teams, and O'Reilly Family Events Center, which opened fall 2010, is now the new home to the Drury University Panthers men's and women's basketball teams. Springfield Rugby Football Club (SRFC) was established in 1983 and is a well-known rugby club in the Midwestern United States. SRFC plays in Division III of the Frontier Region of the Western Conference and runs teams for men, women and youth of the area.

| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Springfield Cardinals | Texas League, Baseball | Hammons Field | 2005 | 1 |

| Springfield Lasers | WTT, Team tennis | Cooper Tennis Complex | 1996 | 1 |

Culture

Like many cities across the nation, Springfield has seen a resurgence in its downtown area. Many of the older buildings have been, and are continuing to be, renovated into mixed-use buildings such as lofts, office space, restaurants, coffee shops, bars, boutiques, and music venues. The Downtown Springfield CID (Community Improvement District) has historic theaters that have been restored to their original state, including the Gillioz Theatre and the Landers Theatre.

In 2001, Phase I of Jordan Valley Park opened along with the Mediacom Ice Park. Phase II of Jordan Valley Park was completed in 2012. 2001 also saw the opening of The Creamery Arts Center, a city-owned building inside Jordan Valley Park. It is home to the Springfield Regional Arts Council, Springfield Regional Opera, Springfield Ballet, and the Springfield Symphony Orchestra and provides office and meeting space for other arts organizations which serve the community. The center has been renovated to include two art galleries with monthly exhibitions, an Arts Library, rehearsal studios, and classrooms offering art workshops and hands-on activities. The facilities also include an outdoor classroom.

A March 2009 New York Times article[49] described the history and ascendancy of cashew chicken in Springfield, where local variations of the popular Chinese dish are ubiquitous. There are several arts events that occur annually including the Walnut Street Arts Fest and the Missouri Literary Festival.[50][51] The First Friday Art Walk occurs the first Friday of every month.

Country music

During the 1950s, Springfield ranked third in the U.S. for originating network television programs, behind New York and Hollywood. Four nationally broadcast television series originated from the city between 1955 and 1961: Ozark Jubilee and its spin-off, Five Star Jubilee; Talent Varieties; and The Eddy Arnold Show. All were carried live by ABC except for Five Star Jubilee on NBC and were produced by Springfield's Crossroads TV Productions, owned by Ralph D. Foster. Many of the biggest names in country music frequently visited or lived in Springfield at the time. City officials estimated the programs meant about 2,000 weekly visitors and "over $1,000,000 in fresh income."[52]

Staged at the Jewell Theatre (demolished in 1961), Ozark Jubilee was the first national country music TV show to feature top stars and attract a significant viewership. Five Star Jubilee, produced from the Landers Theatre, was the first network color television series to originate outside of New York City or Hollywood.[53] Ironically, Springfield's NBC affiliate, KYTV-TV (which helped produce the program), was not equipped to broadcast in color and aired the show in black-and-white.

The ABC, NBC and Mutual radio networks also all carried country music shows nationally from Springfield during the decade, including KWTO'S Korn's-A-Krackin' (Mutual).

The Ozark Hillbilly Medallion

The Springfield Chamber of Commerce once presented visiting dignitaries with an "Ozark Hillbilly Medallion" and a certificate proclaiming the honoree a "hillbilly of the Ozarks." On June 7, 1953, U.S. President Harry Truman received the medallion after a breakfast speech at the Shrine Mosque for a reunion of the 35th Division. Other recipients included US Army generals Omar Bradley and Matthew Ridgway, US Representative Dewey Short, J. C. Penney, Johnny Olson, Ralph Story and disc jockey Nelson King.[54][55]

Museums and other points of interest

|

|

National Register of Historic Places

Transportation

Highways

Springfield is served by Interstate 44, which connects the city with St. Louis and Tulsa, Oklahoma. Route 13 (Kansas Expressway) carries traffic north towards Kansas City. U.S. Route 60, U.S. Route 65, and U.S. Route 160 pass through the city.

Major streets include Glenstone Avenue, Sunshine Street (Missouri Route 413), National Avenue, Division Street, Campbell Avenue, Kansas Expressway, Battlefield Road, Republic Road, West Bypass, Chestnut Expressway and Kearney Street.

Springfield is also the site of the first diverging diamond interchange within the United States, at the intersection of I-44 and MO-13 (Kansas Expressway) (at 37°15′01″N 93°18′39″W / 37.2503°N 93.3107°W).

U.S. Route 66 and U.S. Route 166 formerly passed through Springfield, and sections of historic US 66 can still be seen in the city. US 166's eastern terminus was once in the northeast section of the city, and US 60 (westbound) originally ended in downtown Springfield. US 60 now goes through town on James River Freeway. In mid-November 2013, the city began discussing plans to upgrade sections of Schoolcraft Freeway (Highway 65) and James River Freeway (Highway 60) through the city to Interstate 44. The main reason is to minimize confusion should there be an incident on I-44 as a detour route.

Airport

Springfield-Branson National Airport (SGF) serves the city with direct flights to 10 cities. It is the principal air gateway to the Springfield region. The Downtown Airport is also a public-use airport located near downtown. In May 2009, the Springfield-Branson airport opened a new passenger terminal. Financing included $97 million in revenue bonds issued by the airport and $20 million of discretionary federal aviation funds, with no city taxes used. The building includes 275,000 square feet (25,500 m2), 10 gates (expandable to 60) and 1,826 parking spaces. Direct connections from Springfield are available to Atlanta, Charlotte, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, Destin/Ft. Walton Beach, Ft. Myers, Houston, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Orlando, Phoenix and Tampa. No international flights have regular service into Springfield-Branson, but it does serve international charters.

Trains

Passenger trains have not served Springfield since 1967, but more than 65 freight trains travel to, from, and through the city each day. Springfield was once home to the headquarters and main shops of the St. Louis-San Francisco Railroad (Frisco). Into the 1960s, the Kansas City-Florida Special ran from Kansas City to Jacksonville, Florida, and the Sunnyland ran between Kansas City and Birmingham and New Orleans. The railroad also operated two daily trains to St. Louis through Springfield: the Meteor and the Will Rogers. Both continued southwest to Oklahoma City via Tulsa. The Meteor continued on to Lawton, Oklahoma.

The Frisco was absorbed by the Burlington Northern (BN) in 1980, and in 1994 the BN merged with the Santa Fe, creating the current Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) Railway. BNSF has three switch yards (two small) in Springfield. Mainlines to and from Kansas City, St. Louis, Memphis and Tulsa converge at the railroad's yard facility in northern Springfield. In October 2006, BNSF announced plans to upgrade its Tulsa and Memphis mainlines into Springfield to handle an additional four to six daily intermodal freight trains between the West Coast and the Southeast. The Missouri and Northern Arkansas Railroad also operates several miles of (former Missouri Pacific) industrial track in the city.

Healthcare

Springfield is a regional medical center with six hospitals and more than 2,200 beds. The city's health care system offers every specialty listed by the American Medical Association. Two of the top 100 hospitals in the U.S. (CoxHealth and Mercy Health System) are in Springfield, and both are in the midst of expansion projects. The industry employs 30,000 people in the Springfield metro area.

The United States Medical Center for Federal Prisoners, one of six federal institutions designed to handle federal inmates' medical concerns, is located at the corner of W. Sunshine Street and Kansas Expressway.[56]

Media

The city's major daily newspaper is the Springfield News-Leader. Other newspapers for Springfield include Daily Events (daily), Community Free Press (bi-weekly), Springfield Business Journal (weekly), The Standard (weekly), and TAG Magazine (monthly).

Television stations broadcast in Springfield include KYTV (NBC/Weather), KGHZ (ABC), KCZ-TV (CW), KOLR (CBS), KOZK (PBS/Create/OPT), KRBK (FOX/MeTV), KOZL (independent, MyNetworkTV), KWBM (Daystar), KRFT (Mundo/TNN/RETRO TV). The Springfield Designated Market Area (SPR-DMA) is the 75th largest in the United States. The area is composed of 31 counties in southwest Missouri and Arkansas. There are 423,010 television-owning households.[57]

The radio stations received in Springfield are:

Sister cities

See also

- List of people from Springfield, Missouri

- List of tallest buildings in Springfield, Missouri

- The Springfield Three

- Tiny Town

Notes

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ Official records for Springfield were kept at downtown from January 1888 to December 1939, Downtown Airport from January 1940 to July 1940, and at Springfield–Branson National Airport since August 1940. For more information, see ThreadEx.

References

- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Springfield, Missouri

- ^ a b "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-07-14. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- ^ a b c "City and Town Population Totals: 2010-2017". Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ Dark, Phyllis & Harris. Springfield of the Ozarks: An Illustrated History. Windsor Publications, 1981. ISBN 0-89781-028-7.

- ^ a b c d e f "History of Greene County, Missouri". Thelibrary.springfield.missouri.org. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ^ a b c d "A brief history of Greene County, Missouri". www.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ^ "History of Greene County, Missouri". thelibrary.org. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ^ "History of Greene County, Missouri". thelibrary.org. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- ^ Creative, Demi. "Greenway Trails | Ozark Greenways". ozarkgreenways.org. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ^ a b c d "Springfield History - Springfield Missouri Travel & Tourism - Ozarks/Midwest Vacations". www.springfieldmo.org. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ^ "Zagonyi's Charge". thelibrary.org. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ^ https://thelibrary.org/lochist/history/holcombe/grch30pt1.html

- ^ a b c "Ozarks Afro-American History Museum Online | Springfield: April 14, 1906 · Lynchings and Exodus". oaahm.omeka.net. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- ^ Kimberly Harper, White Man's Heaven: The Lynching and Expulsion of Blacks in the Southern Ozarks, 1894-1909, University of Arkansas Press, 2012, pp. 144-145

- ^ a b Lynching in America/ Supplement: Lynchings by County, 3rd edition, Montgomery, Alabama: Equal Justice Initiative, 2015, p. 7

- ^ a b Harper (2012), White Man's Heaven

- ^ "Historic Joplin » Blog Archive » 105th Anniversary of Springfield's 'Easter Offering'". www.historicjoplin.org. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- ^ "Missouri Breeding Bird Atlas 1986 - 1992: The Natural Divisions of Missouri". Mdc.mo.gov. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

- ^ "Wind- Average Wind Speed- (MPH)". 2011-03-03. Archived from the original on 2011-03-03. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Wind Energy Resource Atlas of the United States". RREDC - NREL. 1986. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ "Average Relative Humidity(%)". NCDC - NOAA. 2001. Archived from the original on 1 November 2001. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

NOAAwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Van Riper, Tom (2007-07-20). "In Pictures: America's Wildest Weather Cities: No. 9: Most Variety (biggest variations in temperature, precipitation, wind), Springfield, Mo". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2016-03-10.

- ^ Haugland, Matt (1998). "Cities with most weather variety". Weather Pages. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Springfield, MO". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for SPRINGFIELD/REGIONAL AP MO 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-02. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Our Community". Coxhealth.com. 2006-09-30. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ^ "The Role of Metro Areas in the U.S. Economy" (PDF). U.S. Conference of Mayors. March 2006. p. 119. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-16. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Springfield Business Development Corporation". Business4springfield.com. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ^ "Major Employers | Springfield Regional Economic Partnership". Springfieldregion.com. 2014-06-20. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ^ "Springfield now largest Missouri school district". Springfield News-Leader. 2011-12-14.

- ^ "Missouri State University sets another fall enrollment record". 20 September 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Miller, Mark (2010-09-28). "Drury University's fall 2010 census reveals record enrollment". Drury.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Drury University: Quick Stats". Drury.edu. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ^ "New students, new spaces at OTC this fall". Otc.edu. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ^ "SBU-Springfield Campus]". Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ^ "Springfield-Greene County Park Board About Us"

- ^ "History and Background of Nathanael Greene Close Memorial Park"

- ^ "Springfield-Greene County Park Board Facilities"

- ^ "Ozark Greenways Maps"

- ^ "Springfield CNC"

- ^ "National Park Service - Wilson's Creek National Battlefield"

- ^ Edge, John T., Missouri Chinese: Two Cultures Claim This Chicken, March 10, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/11/dining/11cashew.html

- ^ "First Friday Art Walk – Springfield, MO |". Ffaw.org. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ^ "Missouri Literary Festival, Springfield". Missouriliteraryfestival.org. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ^ Dessauer, Phil "Springfield, Mo.-Radio City of Country Music" (April, 1957), Coronet, p. 152

- ^ "'Jubilee' Turning to Color TV" (April 30, 1961), Springfield Leader-Press

- ^ Dessauer, Phil "Springfield, Mo.-Radio City of Country Music" (April, 1957), Coronet, p. 151

- ^ "First C&W Deejay Conclave" (June 23, 1956), The Billboard, p. 40

- ^ "MCPF Springfield." Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved on May 20, 2010.

- ^ "Sportstvjobs.com". Sportstvjobs.com. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ^ a b "Interactive City Directory". Sister Cities International. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

Further reading

- McIntyre, Stephen L., ed. Springfield's Urban Histories: Essays on the Queen City of the Missouri Ozarks (Springfield: Moon City Press, 2012) 352 pp.

External links

- City of Springfield

- Springfield Convention & Visitors Bureau

- Springfield Area Chamber of Commerce

- Downtown Springfield

- Historic maps of Springfield in the Sanborn Maps of Missouri Collection at the University of Missouri