Yukon

Yukon | |

|---|---|

| Country | Canada |

| Confederation | June 13, 1898 (9th) |

| Government | |

| • Commissioner | Angélique Bernard |

| • Premier | Sandy Silver |

| Legislature | Yukon Legislative Assembly |

| Federal representation | Parliament of Canada |

| House seats | 1 of 338 (0.3%) |

| Senate seats | 1 of 105 (1%) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 40,232 |

| GDP | |

| • Rank | 12th |

| • Total (2017) | C$3.089 billion[1] |

| • Per capita | C$75,141 (3rd) |

| Canadian postal abbr. | YT |

| Postal code prefix | |

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |

Yukon[2] (/ˈjuːkɒn/ ⓘ; French: [jykɔ̃]; also commonly called the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It has the smallest population of any province or territory in Canada, with a population of 35,874 people. Whitehorse, the territorial capital and Yukon's only city, is the largest settlement in any of the three territories.[3]

Yukon was split from the Northwest Territories in 1898 and was originally named the Yukon Territory. The federal government's Yukon Act, which received royal assent on March 27, 2002, established Yukon as the territory's official name,[2] though Yukon Territory is also still popular in usage and Canada Post continues to use the territory's internationally approved postal abbreviation of YT.[4] Though officially bilingual (English and French), the Yukon government also recognizes First Nations languages.

At 5,959 m (19,551 ft), Yukon's Mount Logan, in Kluane National Park and Reserve, is the highest mountain in Canada and the second-highest on the North American continent (after Denali in the U.S. state of Alaska). Most of Yukon has a subarctic climate, characterized by long, cold winters and brief, warm summers. The Arctic Ocean coast has a tundra climate.

Notable rivers include the Yukon River (after which the territory was named), as well as the Pelly, Stewart, Peel, White, and Tatshenshini rivers.

Etymology

The territory is named after the Yukon River, the longest river in Yukon. The name itself is from a contraction of the words in the Gwich'in phrase chųų gąįį han, which means white water river and refers to "the pale colour" of glacial runoff in the Yukon River.[5][6]

Geography

The territory is the approximate shape of a right triangle, bordering the U.S. state of Alaska to the west and northwest for 1,210 km (752 mi) mostly along longitude 141° W, the Northwest Territories to the east and British Columbia to the south.[7] Its northern coast is on the Beaufort Sea. Its ragged eastern boundary mostly follows the divide between the Yukon Basin and the Mackenzie River drainage basin to the east in the Mackenzie mountains.

Most of the territory is in the watershed of its namesake, the Yukon River. The southern Yukon is dotted with a large number of large, long and narrow glacier-fed alpine lakes, most of which flow into the Yukon River system. The larger lakes include Teslin Lake, Atlin Lake, Tagish Lake, Marsh Lake, Lake Laberge, Kusawa Lake and Kluane Lake. Bennett Lake on the Klondike Gold Rush trail is a lake flowing into Nares Lake, with the greater part of its area within Yukon.

Other watersheds in the territory include the Mackenzie River, the Peel Watershed and the Alsek–Tatshenshini, and a number of rivers flowing directly into the Beaufort Sea. The two main Yukon rivers flowing into the Mackenzie in the Northwest Territories are the Liard River in the southeast and the Peel River and its tributaries in the northeast.

Canada's highest point, Mount Logan (5,959 m or 19,551 ft), is in the territory's southwest. Mount Logan and a large part of Yukon's southwest are in Kluane National Park and Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Other national parks include Ivvavik National Park and Vuntut National Park in the north.

Notable widespread tree species within Yukon are the black spruce and white spruce. Many trees are stunted because of the short growing season and severe climate.[8]

Climate

While the average winter temperature in Yukon is mild by Canadian arctic standards, no other place in North America gets as cold as Yukon during extreme cold snaps. The temperature has dropped down to −60 °C (−76 °F) three times, 1947, 1952, and 1968. The most extreme cold snap occurred in February 1947 when the abandoned town of Snag dropped down to −63.0 °C (−81.4 °F).[9]

Unlike most of Canada where the most extreme heat waves occur in July, August, and even September, Yukon's extreme heat tends to occur in June and even May. Yukon has recorded 36 °C (97 °F) three times. The first time was in June 1969 when Mayo recorded a temperature of 36.1 °C (97 °F). 14 years later this record was almost beaten when Forty Mile recorded 36 °C (97 °F) in May 1983. The old record was finally broken 21 years later in June 2004 when the Mayo Road weather station, located just northwest of Whitehorse, recorded a temperature of 36.5 °C (97.7 °F).[10]

| City | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whitehorse | 21/8 | 70/46 | −11/−19 | 12/−2 |

| Dawson City | 23/8 | 73/46 | −22/−30 | −8/−22 |

| Old Crow | 20/9 | 68/48 | −25/−34 | −13/−29 |

History

Long before the arrival of Europeans, central and southern Yukon was populated by First Nations people, and the area escaped glaciation. Sites of archeological significance in Yukon hold some of the earliest evidence of the presence of human habitation in North America.[12] The sites safeguard the history of the first people and the earliest First Nations of the Yukon.[12]

The volcanic eruption of Mount Churchill in approximately 800 AD in what is now the U.S. state of Alaska blanketed southern Yukon with a layer of ash which can still be seen along the Klondike Highway, and which forms part of the oral tradition of First Nations peoples in Yukon and further south in Canada.

Coastal and inland First Nations had extensive trading networks. European incursions into the area began early in the 19th century with the fur trade, followed by missionaries. By the 1870s and 1880s, gold miners began to arrive. This drove a population increase that justified the establishment of a police force, just in time for the start of the Klondike Gold Rush in 1897. The increased population coming with the gold rush led to the separation of the Yukon district from the Northwest Territories and the formation of the separate Yukon Territory in 1898.

Demographics

The 2016 census reported a Yukon population of 35,874, an increase of 5.8% from 2011.[13] With a land area of 474,712.64 km2 (183,287.57 sq mi), it had a population density of 0.1/km2 (0.2/sq mi) in 2011.[14]

Municipalities by population

| Name | Status[15] | Official name | Incorporation date[16] |

2021 Census of Population[17] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (2021) |

Population (2016) |

Change |

Land area (km2) |

Population density (/km2) | ||||

| Carmacks | Town | Village of Carmacks | November 1, 1984 | 588 | 493 | +19.3% | 36.87 | 15.9 |

| Dawson | Town | City of Dawson[a] | January 9, 1902 | 1,577 | 1,375 | +14.7% | 30.91 | 51.0 |

| Faro | Town | Town of Faro | June 13, 1969 | 440 | 348 | +26.4% | 199.89 | 2.2 |

| Haines Junction | Town | Village of Haines Junction | October 1, 1984 | 688 | 613 | +12.2% | 34.30 | 20.1 |

| Mayo | Town | Village of Mayo | June 1, 1984 | 188 | 200 | −6.0% | 0.98 | 191.8 |

| Teslin | Town | Village of Teslin | August 1, 1984 | 239 | 255 | −6.3% | 3.77 | 63.4 |

| Watson Lake | Town | Town of Watson Lake | April 1, 1984 | 1,133 | 1,083 | +4.6% | 109.77 | 10.3 |

| Whitehorse | City | City of Whitehorse | June 1, 1950 | 28,201 | 25,085 | +12.4% | 413.94 | 68.1 |

| Total municipalities | 33,054 | 29,452 | +12.2% | 830.43 | 39.8 | |||

| Yukon | 40,232 | 35,874 | +12.1% | 472,345.44 | 0.1 | |||

Ethnicity

This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (April 2017) |

Yukon population by visible minority and Indigenous identity (2016[19][20])

According to the 2006 Canada Census the majority of the territory's population was of European descent, although it has a significant population of First Nations communities across the territory.

The top ten ancestries were:[21]

| Rank | Ethnic group | Population |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | English | 8,795 |

| 2 | North American First Nations | 7,705 |

| 3 | Scottish | 7,000 |

| 4 | Canadian | 6,075 |

| 5 | Irish | 5,735 |

| 6 | German | 4,835 |

| 7 | French | 4,330 |

| 8 | Ukrainian | 1,620 |

| 9 | Dutch (Netherlands) | 1,475 |

| 10 | Norwegian | 1,340 |

The 2011 National Household Survey examined Yukon's ethnocultural diversity and immigration. At that time, 87.7% of residents were Canadian-born and 24.2% were of Aboriginal origin. The most common countries of birth for immigrants were the United Kingdom (15.9%), the Philippines (15.0%), and the United States (13.2%). Among very recent immigrants (between 2006 and 2011) living in Yukon, 63.5% were born in Asia.[22]

Language

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The most commonly reported mother tongue among the 33,145 single responses to the 2011 Canadian census was English at 28,065 (85%).[24] The second-most common was 1,455 (4%) for French.[24] Among 510 multiple respondents, 140 of them (27%) reported a mother tongue of both English and French, while 335 (66%) reported English and a "non-official language" and 20 (4%) reported French and a "non-official language".[24]

The Yukon Language Act "recognises the significance" of aboriginal languages in Yukon, although only English and French are available for laws, court proceedings, and legislative assembly proceedings.[25]

Religion

This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (May 2012) |

The 2011 National Household Survey reported that 49.9% of Yukoners reported having no religious affiliation, the highest percentage in Canada. The most frequently reported religious affiliation was Christianity, reported by 46.2% of residents. Of these, the most common denominations were the Catholic Church (39.6%), the Anglican Church of Canada (17.8%) and the United Church of Canada (9.6%).[26]

Economy

Yukon's historical major industry was mining (lead, zinc, silver, gold, asbestos and copper). The government acquired the land from the Hudson's Bay Company in 1870 and split it from the Northwest Territories in 1898 to fill the need for local government created by the population influx of the gold rush. Thousands of these prospectors moved to the territory, ushering a period of Yukon history recorded by authors such as Robert W. Service and Jack London. The memory of this period and the early days of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, as well as the territory's scenic wonders and outdoor recreation opportunities, makes tourism the second most important industry in the territory.

Manufacturing, including furniture, clothing, and handicrafts, follows in importance, along with hydroelectricity. The traditional industries of trapping and fishing have declined. As of 2012, the government sector directly employs approximately 6,300 out of a labour force of 20,800, on a population of 27,500.[27][28]

On May 1, 2015, Yukon modified its Business Corporations Act,[29][30][31] in an effort to attract more benefits and participants to its economy. One amendment to the BCA lets a proxy be given for voting purposes. Another change will allow directors to pursue business opportunities declined by the corporation, a practice off-limits in most other jurisdictions due to the inherent potential for conflicts of interest.[32] One of the changes will allow a corporation to serve as a director of a subsidiary registered in Yukon.[33] The legislation also allows companies to add provisions in their articles of incorporation giving directors blanket approval to sell off all of the company's assets without requiring a shareholder vote.[33] If provided for by a unanimous shareholders agreement, a corporation is not required to have directors at all.[34] There is increased flexibility regarding the location of corporate records offices, including the ability to maintain a records office outside of Yukon so long as it is accessible by electronic means.[34]

Tourism

Yukon's tourism motto is "Larger than life".[35] Yukon's tourism relies heavily on its natural environment, and there are many organized outfitters and guides available for activities such as but not limited to hunting, angling, canoeing/kayaking, hiking, skiing, snowboarding, ice climbing and dog sledding. These activities are offered both in an organized setting or in the backcountry, which is accessible by air or snowmobile. Yukon's festivals and sporting events include the Adäka Cultural Festival, Yukon International Storytelling Festival, and the Yukon Sourdough Rendezvous. Yukon's latitude enables the view of aurora borealis.

The Government of Yukon maintains a series of territorial parks including,[36] parks (Herschel Island Qikiqtaruk Territorial Park,[37] including Tombstone Territorial Park,[38] and Fishing Branch Ni'iinlii'njik Park.[39] Coal River Springs Territorial Park)[40] Parks Canada, a federal agency of the Government of Canada, also maintains three national parks and reserves within the territory, Kluane National Park and Reserve, Ivvavik National Park, and Vuntut National Park.

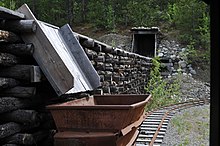

Yukon is also home to 12 National Historic Sites of Canada. The sites are also administered by Parks Canada, with five of the 12 sites being located within national parks. The territory is host to a number of museums, including the Copperbelt Railway & Mining Museum, the SS Klondike boat museum, the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre in Whitehorse; as well as the Keno City Mining Museum in Keno City. The territory also holds a number of enterprises that allows tourists to experience pre-colonial and modern cultures of Yukon's First Nations and Inuit peoples.[41]

Culture

As noted above, the "aboriginal identity population" makes up a substantial minority, accounting for about 26 percent. Notwithstanding, the aboriginal culture is strongly reflected in such areas as winter sports, as in the Yukon Quest sled dog race. The modern comic-book character Yukon Jack depicts a heroic aboriginal persona. Similarly, the territorial government also recognizes that First Nations and Inuit languages plays a part in cultural heritage of the territory; these languages include Tlingit, and the less common Tahltan, as well as seven Athapaskan languages, Upper Tanana, Gwitchin, Hän, Northern Tutchone, Southern Tutchone, Kaska and Tagish, some of which are rare.[42]

Yukon also has a wide array of cultural and sporting events that attract artists, local residents, and tourists. Annual events include the Adäka Cultural Festival, Dawson City Music Festival, Yukon International Storytelling Festival, Yukon Quest dog sled race, Yukon Sourdough Rendezvous, as well as Klondike Gold Rush memorials.[43][44] Northern Lights Centre,[45][46]

Arts

With the Klondike Gold Rush, a number of folk songs from Yukon became popular, including "Rush to the Klondike" (1897, written by W. T. Diefenbaker), "The Klondike Gold Rush", "I've Got the Klondike Fever" (1898) and "La Chanson du Klondyke".

By far the strongest cultural and tourism aspect of Yukon is the legacy of the Klondike Gold Rush (1897–1899), which inspired such contemporary writers of the time as Jack London, Robert W. Service, and Jules Verne, and which continues to inspire films and games, such as Mae West's Klondike Annie and The Yukon Trail .

Government

In the 19th century, Yukon was a segment of North-Western Territory that was administered by the Hudson's Bay Company, and then of the Northwest Territories administered by the federal Canadian government. It only obtained a recognizable local government in 1895 when it became a separate district of the Northwest Territories.[47] In 1898, it was made a separate territory with its own commissioner and an appointed Territorial Council.[48]

Prior to 1979, the territory was administered by the commissioner who was appointed by the federal Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. The commissioner had a role in appointing the territory's Executive Council, served as chair, and had a day-to-day role in governing the territory. The elected Territorial Council had a purely advisory role. In 1979, a significant degree of power was devolved from the commissioner and the federal government to the territorial legislature which, in that year, adopted a party system of responsible government. This change was accomplished through a letter from Jake Epp, the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, rather than through formal legislation.

In preparation for responsible government, political parties were organized and ran candidates to the Yukon Legislative Assembly for the first time in 1978. The Progressive Conservatives won these elections and formed the first party government of Yukon in January 1979. The Yukon New Democratic Party (NDP) formed the government from 1985 to 1992 under Tony Penikett and again from 1996 under Piers McDonald until being defeated in 2000. The conservatives returned to power in 1992 under John Ostashek after having renamed themselves the Yukon Party. The Liberal government of Pat Duncan was defeated in elections in November 2002, with Dennis Fentie of the Yukon Party forming the government as premier.

The Yukon Act, passed on April 1, 2003, formalized the powers of the Yukon government and devolved additional powers to the territorial government (e.g., control over land and natural resources). As of 2003, other than criminal prosecutions, the Yukon government has much of the same powers as provincial governments, and the other two territories are looking to obtaining the same powers.[citation needed] Today the role of commissioner is analogous to that of a provincial lieutenant governor; however, unlike lieutenant-governors, commissioners are not formal representatives of the Queen but are employees of the federal government.

At the federal level, Yukon is represented in the Parliament of Canada by a single Member of Parliament and one senator. Members of Parliament from Canadian territories are full and equal voting representatives and residents of the territory enjoy the same rights as other Canadian citizens. One Yukon Member of Parliament, Erik Nielsen, was the Deputy Prime Minister under the government of Brian Mulroney, while another, Audrey McLaughlin, was the leader of the federal New Democratic Party from 1989 to 1995.

Federal representation

The entire territory is one riding (electoral district) in the House of Commons of Canada, also called Yukon. The current holder of the seat is Liberal Member of Parliament Larry Bagnell following his victory in the 2015 federal election.

Yukon is allocated one seat in the Senate of Canada and has been represented by three Senators since the position was created in 1975. The Senate position is held by Conservative senator Daniel Lang, who was appointed on the advice of then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper on December 22, 2008.[49][50] It was previously filled by Ione Christensen, of the Liberal Party. Appointed to the Senate in 1999 by Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, Christensen resigned in December 2006 to help her ailing husband. From 1975 to 1999, Paul Lucier (Liberal) served as Senator for Yukon. Lucier was appointed by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau.

First Nations

| Much of the population of the territory is First Nations. An umbrella land claim agreement representing 7,432 members of 14 different First Nations was signed with the federal government in 1993. Eleven of the 14 Yukon First Nations have negotiated and signed comprehensive land claim and self-government agreements. The 14 First Nations speak eight different languages.

The territory once had an Inuit settlement, located on Herschel Island off the Arctic coast. This settlement was dismantled in 1987 and its inhabitants relocated to the neighbouring Northwest Territories. As a result of the Inuvialuit Final Agreement, the island is now a territorial park and is known officially as Qikiqtaruk Territorial Park, Qikiqtaruk being the name of the island in Inuvialuktun. |

|

Transportation

Before modern forms of transportation, the rivers and mountain passes were the main transportation routes for the coastal Tlingit people trading with the Athabascans of which the Chilkoot Pass and Dalton Trail, as well as the first Europeans.

Air

Erik Nielsen Whitehorse International Airport serves as the air transport infrastructure hub, with scheduled direct flights to Vancouver, Kelowna, Calgary, Edmonton, Yellowknife, Inuvik, Ottawa, Dawson City, Old Crow and Frankfurt.[65] Whitehorse International Airport is also the headquarters and primary hub for Air North, Yukon's Airline. Every Yukon community is served by an airport or community aerodrome.[citation needed] The communities of Dawson City and Old Crow have regularly scheduled service through Air North. Air charter businesses exist primarily to serve the tourism and mining exploration industries.[citation needed]

Rail

The railway ceased operation in the 1980s with the first closure of the Faro mine. It is now run during the summer months for the tourism season, with operations as far as Carcross.

Roads

Today, major land routes include the Alaska Highway, the Klondike Highway (between Skagway and Dawson City), the Haines Highway (between Haines, Alaska, and Haines Junction), and the Dempster Highway (linking Inuvik, Northwest Territories to the Klondike Highway, and the only road access route to the Arctic Ocean, in Canada), all paved except for the Dempster. Other highways with less traffic include the "Robert Campbell Highway" linking Carmacks (on the Klondike Highway) to Watson Lake (Alaska Highway) via Faro and Ross River, and the "Silver Trail" linking the old silver mining communities of Mayo, Elsa and Keno City to the Klondike Highway at the Stewart River bridge. Air travel is the only way to reach the far-north community of Old Crow.

Waterways

From the Gold Rush until the 1950s, riverboats plied the Yukon River, mostly between Whitehorse and Dawson City, with some making their way further to Alaska and over to the Bering Sea, and other tributaries of the Yukon River such as the Stewart River. Most of the riverboats were owned by the British-Yukon Navigation Company, an arm of the White Pass and Yukon Route, which also operated a narrow gauge railway between Skagway, Alaska, and Whitehorse.

See also

References

- ^ "Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, by province and territory (2017)". Statistics Canada. September 22, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ a b "Yukon Act, SC 2002, c 7". CanLII. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "Population and Dwelling Count Highlight Tables, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Table 8 Abbreviations and codes for provinces and territories, 2011 Census". Statistics Canada. December 30, 2015. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ "Dear Sir, I have great pleasure in informing you that I have at length after much trouble and difficulties, succeed[ed] in reaching the 'Youcon', or white water River, so named by the (Gwich'in) natives from the pale colour of its water. …, I have the honour to Remain Your obᵗ Servᵗ, John Bell" Hudson's Bay Company Correspondence to George Simpson from John Bell (August 1, 1845), HBC Archives, D.5/14, fos. 212-215d, also quoted in, Coates, Kenneth S.; Morrison, William R. (1988). Land of the Midnight Sun: A History of the Yukon. Hurtig Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 0-88830-331-9. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ In Gwich'in, adjectives, such as choo [big] and gąįį [white], follow the nouns that they modify. Thus, white water is chųų gąįį [water white]. White water river is chųų gąįį han [water white river]. Peter, Katherine (1979). Dinjii Zhuh Ginjik Nagwan Tr'iłtsąįį: Gwich'in Junior Dictionary (PDF). Univ. of Alaska. pp. ii (ą, į, ų are nasalized a, i, u), xii (adjectives follow nouns), 19 (nitsii or choo [big]), 88 (ocean = chųų choo [water big]), 105 (han [river]), 142 (chųų [water]), 144 (gąįį [white]). Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ "Boundary Facts". International Boundary Commission. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

Length of boundary by province – Yukon- 1,210 km or 752 miles

- ^ Carl Duncan, "The Dempster: Highway to the Arctic Archived May 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine" accessed 2009.10.22.

- ^ "Life at Minus 80: The Men of Snag". The Weather Doctor. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ a b "National Climate Data and Information Archive". Environment Canada. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ "Whitehorse – Geography and Climate". www.yukoncommunities.yk.ca. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ a b Services, Cultural. Archaeology Program. Department of Tourism and Culture. [Online] March 8, 2011. [Cited: April 7, 2012.] http://www.tc.gov.yk.ca/archaeology.html.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

2016censuswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2011 and 2006 censuses (Yukon)". Statistics Canada. January 13, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ "Yukon Communities". Yukon Government: Department of Community Services. November 7, 2013. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ "Association of Yukon Communities Incorporation Dates". Association of Yukon Communities. Archived from the original on June 15, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), Yukon". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ "Municipal Act" (PDF). Government of Yukon. 2002. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "Aboriginal Peoples Highlight Tables". 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables". 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Statistics Canada. "Ethnic origins, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories".

- ^ "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity, 2011 National Household Survey" (PDF). Statistics Canada. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ Council of Yukon First Nations

- ^ a b c d "Focus on Geography Series, 2011 Census, Yukon". Statistics Canada. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ "Language Act, Statues of the Yukon (2002)" (PDF). Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity, 2011 National Householder" (PDF). 2.statcan.ca. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Archived – Public sector employment, wages and salaries, seasonally unadjusted and adjusted". Statistics Canada. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Labour force characteristics by province, territory and economic region, annual (x 1,000)". Statistics Canada. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ gov.yk.ca: "Business Corporations Act" Archived October 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, May 1, 2015

- ^ gov.yk.ca: "O.I.C. 2015/06 Business Corporations Act" Archived October 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, May 1, 2015

- ^ gov.yk.ca: "O.I.C. 2015/07 Societies Act" Archived October 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, May 1, 2015

- ^ cbc.ca: "Go north, not west: Yukon lures businesses with new company rules", May 1, 2015

- ^ a b theglobeandmail.com: "Yukon's move to draw corporations worries shareholders coalition", June 18, 2015

- ^ a b deallawwire.com: "Changes of note to the Yukon Business Corporations Act", June 2, 2015

- ^ Travel Yukon Archived October 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Territorial Parks". Environmentyukon.gov.yk.ca. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Herschel Island Qikiqtaruk Territorial Park". Environmentyukon.gov.yk.ca. Archived from the original on March 13, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Tombstone Territorial Park". Environmentyukon.gov.yk.ca. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Fishing Branch Ni'iinlii'njik Park". Environmentyukon.gov.yk.ca. Archived from the original on December 18, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Coal River Springs Territorial Park". Environmentyukon.gov.yk.ca. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Yukon First Nation Tourist Association". Yfnta.org. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ Yukon Territory History and Culture, Pinnacle Travel

- ^ "Dawson Music Festival". Dcmf.com. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre". Beringia.com. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Northern Lights Centre". Northernlightscentre.ca. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Whitehorse fish ladder". Yukonenergy.ca. February 1, 2011. Archived from the original on September 3, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ Coates and Morrison, p.74

- ^ Coates and Morrison, p.103

- ^ "Senators – Detailed Information". Parliament of Canada. Archived from the original on February 5, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

- ^ "Former Yukon MLA named to Senate seat". Cbc.ca. December 22, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Executive Council". Ctfn.ca. Archived from the original on March 7, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Dän nätthe dä̀tthʼi (Chief and Council)". Champagne and Aishihik First Nations. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Governance and Administration". First Nation of Nacho Nyak Dun. October 20, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Chief and Council". Kluane First Nation. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Doris Bill elected Kwanlin Dun chief". CBC News. March 20, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Liard First Nation". Kaska Dena Council. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Chief & Council". Little Salmon Carmacks First Nation. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Ross River Dena Council elects Jack Caesar as chief". CBC News. December 12, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Selkirk First Nation. "The Council". Selkirk First Nation. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Chief and Council". Government of the Ta'an Kwäch'än Council. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Richard Sidney elected chief of Teslin Tlingit Council". CBC News. July 15, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Roberta Joseph new chief of Dawson's Tr'ondek Hwech'in". CBC News. October 10, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Bruce Charlie elected new chief of Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation". CBC News. May 3, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Chief & Council". White River First Nation. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Timetable, Summer 2017" (PDF). Condor Airlines. August 6, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

Further reading

- Coates, Kenneth (1985), Canada's colonies: a history of the Yukon and Northwest Territories, Lorimer, ISBN 0-88862-931-1

- Coates, Ken S.; Morrison, William R. (1988), Land of the Midnight Sun: A History of the Yukon, Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, ISBN 0-88830-331-9

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Cody, William J (2000), Flora of the Yukon Territory, National Research Press, ISBN 0-660-18110-X

- Hart, Ann (2000), Alaska and the Yukon, JPM Publications, ISBN 2-88452-051-1

- Laguna, Frederica De (2000), Travels among the Dena : exploring Alaska's Yukon Valley, Univ. of Washington Press, ISBN 0-295-97902-X

- O'Reilly, Shauna; O'Reilly, Brennan (2009), Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition, Arcadia Pub, ISBN 978-0-7385-7132-4

- Webb, Melody (1993), Yukon: The Last Frontier, University of British Columbia Press, ISBN 0-7748-0441-6

External links

- Government of Yukon

- Yukon at Curlie

- Yukon Attraction & Service Guides

- Immigration Yukon

- William E. Meed Yukon Photography Collection – University of Washington Library

- Henry M. Sarvant Photography Collection – Images depicting his life in Yukon from the University of Washington Library

- "Territorial Battles: Yukon Elections, 1978–2002", Digital Archives, CBC

- Mapping the Way – Yukon First Nation Self-government

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).