Paryphanta busbyi

| Paryphanta busbyi | |

|---|---|

| |

| A drawing of a live individual of Paryphanta busbyi. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| (unranked): | clade Heterobranchia

clade Euthyneura |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. busbyi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Paryphanta busbyi | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Paryphanta busbyi is a species of large predatory land snail, a terrestrial pulmonate gastropod mollusk in the family Rhytididae.

Distribution

The distribution of Paryphanta busbyi includes the Northern parts of North Island, New Zealand: Kaitaia, Hokianga, Mangonui, Bay of Islands, Otonga East, Mania Hill, Whangārei,[3] Brynderwyn Range, Hen Island, Woodcocks and Warkworth, where is its southern native distribution.[4] Localitions with introduced distribution include Little Huia in Waitākere Ranges, Waiuku in Āwhitu Peninsula and Kaimai Ranges.[4]

Its distribution is coincident in range with the kauri forest.[3]

The type locality is New Zealand.[4] The type specimen is stored in Natural History Museum, London.[4]

Shell description

The shell is large, broadly umbilicated, depressed and subdiscoidal. The shell is opaque and shining. The colour is deep green, usually with some radial streaks of blackish-green.[3]

There is a sculpture on the nucleus containing oblique and arcuate radial plaits. The succeeding two whorls are distinctly rugose. On the post-embryonic whorls more or less distinct spiral cords appear, which are first directed upwards, but become spiral on the last whorl. Plaits are distant, low, broadly rounded, varying in number from about 5 to 10 and absent on the base. There are retractive distant growth-plications, which are prominently and closely plicate at the suture. The whole surface of the shell is microscopically decussated by exceedingly fine and dense radiate and spiral lines, the latter slightly wavy. The periostracum is thick, glabrous, shining, overhanging the peristome. The spire is flat, very little raised and broadly convex. The protoconch has 2 whorls, flatly convex, the volutions rather rapidly increasing. The shell has 4½ whorls, that are rapidly increasing. The last whorl is very large, slightly convex, periphery and base rounded, the body-whorl more or less deflexed anteriorly. Suture well impressed.[3]

The aperture is within shining-blue. Aperture obliquely lunate-oval. Peristome is simple, inflexed throughout. The columella is very oblique, slightly arcuate, and shortly reflexed above. Umbilicus broad, perspective and deep.[3]

The width of the shell is 60–79 mm. The height of the shell is 33–44 mm.[4] The width of the type specimen is 66 × 53 mm, the height of the shell is 29 mm.[3]

|

|

|

The shell of Paryphanta busbyi has very thick periostracum and only few micrometre thick calcium layer. When the shell is kept in dry environment, the shell will explode into pieces, because its periostracum shrinks.[5][6]

The embryonic shell globose, flat above, of 2 whorls, narrowed toward the base and narrowly umbilicate. The width of the shell is 10 mm. The height of the shell is 9 mm.[3]

Anatomy

The animal is bluish-black, with the foot-sole perhaps a shade lighter in colour. On the head and neck are a few regular rows of rugae, somewhat quadrate in outline; on other parts of the body the rugae appear to be oval-shaped, irregular in size, and not forming continuous rows. The mantle has a sharp even margin, and a deeply incised line or groove rather less than 2 mm from the edge. On the underside of the mantle is the usual prominent lappet which conceals the respiratory and anal pores, and in addition to this is a long narrow fold on the left side.[7]

The retractor muscles: The buccal mass and pedal retractors are fused together posteriorly where they unite with the columella of the shell. The buccal retractor rests dorsally on the pedal muscles, and forms a broad powerful band. The pedal retractors are continuously attached to the foot, and there are no free progressively attached pedal retractors as in genus Helix. The ocular retractors branch from the pedal muscles; they bifurcate towards their anterior ends, and supply the inferior tentacle retractors.[7]

The length of the radula is about an inch, and 0.4 inch in width at the anterior end, tapering to a point posteriorly, with about 104 transverse rows of denticles (tiny teeth). The rows of denticles are forming an obtuse angle of about 130°, salient posteriorly.[8] There is about 100 small denticles in each row, that described and figured by Captain Frederick Hutton with formula 50-0-50,[8] while Robert C. Murdoch gave the formula 52-0-52.[7] Hutton described them like this: Denticles are all aculeate, and similar, with simple bevelled tips. The first five lateral denticles are small. From the sixth they gradually increase in length to about the thirty-fifth, and then get smaller.[8] Murdoch described them like this: A few of the innermost denticles, usually not more than two on each side, are small and very slender. Occasionally one of these slender spicula-like denticles is somewhat separated from the adjoining denticle, and where this occurs it gives to the row the appearance of a central denticle.[7] There is no jaw.[8]

1-2 - buccal mass,

1 - mouth,

2 - pharynx,

3 - retractor muscles of the pharynx,

4 - salivary glands,

5 - salivary ducts,

6 - oesophagus,

7 - stomach.

HG = hermaphordite gland = ovotestis,

HD = hermaphroditic duct,

AG = albumen gland,

UT = spermoviduct,

PR = prostate,

P = penis,

V = vagina,

G = genital pore,

PRM = penis retractor muscle,

M = muscular tissue connecting the oviduct with body-wall.

The digestive system contains enormous buccal mass is and muscular development. Its posterior end is curved down and forward, and a powerful ventral muscle firmly binds it to the more anterior cylindrical portion. The retractor muscle envelopes the posterior end, and from the anterior portion of the mass proceed a number of ventro-lateral muscles, which unite with the immediately adjoining body-walls. The oesophagus enters the buccal cavity dorsally in the anterior fourth. The salivary glands are situate upon the posterior half of the buccal mass; they are fused together in the median line and partly envelope the oesophagus. From the anterior end of each gland proceeds a small salivary duct, which enters the buccal cavity a little below the œsophageal opening. The stomach forms a simple elongated sac, and the tract of the intestine does not appear to differ from Powelliphanta hochstetteri.[7]

The kidney is shortly tongue-shaped, in length less than twice its breadth, about half the length of the lung, and about one and a half times the length of the pericardium; the latter has the usual position on the left margin of the kidney. The ureter continues around the right margin of the kidney, follows the posterior limit of the lung, and opens close to the intestine. From this point the intestine, or rectum, forms a long straight tube. There is a well-marked ridge on the pulmonary wall less than 3 mm. from the side of the rectum, and the narrow area thus defined appears to be the open continuation of the ureter. The above-mentioned ridge examined in section proves to be tubular; it continues into the tissue of the mantle, and appears to unite with the blood-sinus contained therein. The venation of the lung, with the exception of the great pulmonary vein, is very indistinct. This vein runs direct to the auricle, is of considerable breadth, and has an undulating, almost convolute, appearance. On approaching the pneumostome it forms several branches, and the latter, with their accompanying afferent vessels, are fairly well indicated. The vessels on the rectal side of the lung are minute and very much branched, while on the cardiac side only a few traces may be seen.[7]

The suprapedal gland opens between the head and foot immediately below the mouth; it forms a long flattish structure, much folded and lying on the floor of the body cavity. Its posterior end is slightly enlarged, and enclosed in a cavity in the foot, to which it has a muscular attachment. From the termination of the gland the usual tube or duct proceeds through the substance of the foot, but does not form a caudal mucous pit.[7]

The reproductive system anatomically differs from genera Powelliphanta and Wainuia. There is remarkable extreme reduction of male organs in Paryphanta busbyi and the absence of receptaculum seminis (spermatheca). This is resemblance with Schizoglossa novoseelandica. There is a blunt, somewhat triangular, projection of the vaginal wall, with a retractor muscle proceeding to the adjoining body-wall; this is the only evidence of the male organs before any of the surrounding tissue has been dissected away. On removing this outer tissue a small loop is seen to project from the vaginal wall. This is the posterior termination of the penis, which passes into the vas deferens without any perceptible change, except a slight diminution of the tube. The anterior portion of the vagina forms a wide chamber, closed posteriorly by a valve-like papillar structure; the interior walls are slightly darkish in colour, and weakly longitudinally plicated. The papilla is continuously united with the vaginal wall, and the perforation through its centre is the only communication with the oviduct. Its anterior third projects freely into the anterior vaginal chamber. Its walls are comparatively thick; internally they are lightly longitudinally plicated, and have a whitish epitheloid lining.[7]

The penis opens into the posterior portion of the papillar structure in the form of a small tube; it proceeds through the thick vaginal wall in an oblique anterior direction, and becomes slightly enlarged or bulbous towards its termination. The vas deferens, as previously stated, is free to a very limited extent, and is imbedded in the vaginal wall. Its posterior prostatic course through the prominent folds or plications of the oviduct is tubular, thence open, but for a short distance enfolded on all sides by the above-mentioned plications. From this point to the albumen gland it is a well-marked area of a rusty brownish tint, and somewhat separated from the uteral portion by the longitudinal folds. The uterus is thrown into numerous sacculations, and its interior walls are richly convolutely plicated. There is no indication of a receptaculum seminis. The albumen gland is very large, a usual feature in this group of animals; in outline it is roughly boot-shaped. The hermaphrodite duct enters near the base of the albumen gland; it is a simple straight tube, with several short lesser tubes branching from it and uniting with the several masses which form the hermaphrodite gland. The latter are closely convoluted structures and imbedded in the liver.[7]

When compared with Schizoglossa novoseelandica it is found that the vas deferens in the latter species is free to a greater extent, that no portion of its internal prostatic course appears to be tubular, and there does not appear to be any vaginal papilla. During copulation the atrium is everted; the penis pore is thus brought forward and may be detected on the everted wall. In Paryphanta busbyi the anterior vaginal chamber doubtless undergoes complete eversion, and the vaginal papilla will be thrust outwards to a considerable degree—probably to a much greater extent than the appearance of the organ in its present condition suggests.[7]

Ecology

These large snails live in litter, among plants on the ground and under logs in kauri forests and in shrubland.[4] In some areas they have been reported to at times frequent underground habitats including burrowing deep into soft soil.[9] They are also found in shrublands with non-native species like Hedychium and in forests with non-native plants including plantations of Pinus radiata.[4]

|

|

|

Paryphanta busbyi is often observed to be active when the weather is cool and wet.[4] The activity is most strongly correlated with higher humidity and still air which may assist the snails to track their prey. The snails will then retreat into lairs during the day when lairs are available.[9] In dry weather it is inactive.[4]

Paryphanta busbyi is carnivorous and predatory, feeding on earthworms, insects, insect larvae, snails of the genus Rhytida and on its own species (cannibalism).[4] This snail sometimes lives in trees, very likely in clusters of semiparasitic plants, where it may find its natural food, earthworms.[3]

Life cycle

The eggs are usually laid at the foot of large trees in clusters of four to six eggs,[4] underneath dead leaves.[3] The shape of the eggs is oval and seldom constant in dimensions and ranges from 10.5 × 9.5 mm or 12 × 9 mm to 14 × 10.75 mm. It has white limy egg without cuticle.[10]

It takes 7 years to grow to the size where the width of the shell is 54 mm.[11]

The population density of Paryphanta busbyi is low in comparison of Powelliphanta.[12]

Predators

These snails were not eaten by the Māori people.[3]

Predators of Paryphanta busbyi include rats, pigs,[3] possums, hedgehogs and birds.[4][13] Rats and birds eat the juvenile snails.[12] Pigs eat these snails at all sizes including the eggs, and pigs also destroy the snail's habitat.[4]

Conservation

Already Henry Suter noted in 1913, that this species is being rapidly exterminated by the destruction of its natural habitat - (the kauri forests), by bush-fires, and by rats and pigs.[3] Threats of this species are consuming by introduced animals, habitat fragmentation and habitat modification.[4]

It is protected by Wildlife Act 1953.[14]

Paryphanta spp. was listed in appendix II of CITES and it was removed, because collection is not a significant factor of this species (and the genus) decline.[13]

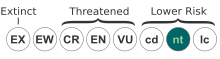

This species is nearly threatened in the 2009 IUCN Red List.[1]

It was listed as in category "Chronically Threatened - Gradual decline" in 2002 New Zealand Threat Classification System lists,[15] and was classified in category C ("third priority of threatened species") according to the Molloy & Davis 1994 ranking system.[4] However it is not in this category in the 2005 New Zealand Threat Classification System lists.[16]

References

This article incorporates public domain text from references.[3][7][8]

- ^ a b Sherley G. (1996) Paryphanta busbyi Archived 18 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine. In: IUCN 2009. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2009.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Accessed 6 December 2009.

- ^ Gray (1841) Annals and Magazine of Natural History 6: 317.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Suter H. (1913) Manual of the New Zealand Mollusca. Wellington, 1120 pp., pages 778-779. Plate 48, figure 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o McGuinness C. A. (2001) The conservation requirements of New Zealand’s nationally threatened invertebrates. Threatened Species Occasional Publication 20. 658 pp. Pages 71-120 Archived 15 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Goldberg R. L. (January 1998) [1]. CONCH-L archives. www.listserv.uga.edu The University Of Georgia. accessed 6 December 2009

- ^ Tryon G. W. (1885) Manual of Conchology, structural and systematic, with illustrations of the species. Second series: Pulmonata. Volume I. page 127.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Murdoch R. (1902) "On the Anatomy of Paryphanta busbyi, Gray". Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand 35: 258-262, plate XXVII.

- ^ a b c d e Hutton F. W. (1881) "Notes on some Pulmonate Mollusca". Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand 14: 151-159.

- ^ a b Gruijters, Wouterus TM (2018). "Predation at a snail's pace. What is needed for a successful hunt?". doi:10.1101/420042.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); External link in|ref= - ^ O'Connor A. C. (June) 1945. "Notes on the Eggs of New Zealand Paryphantidae, With Description of a New Subgenus." Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand 5(1945-46): 54-57.

- ^ Dell R. K. (1953) "A contribution to the study of rates of growth in Paryphanta busbyi (Gray), (Mollusca, Pulmonata)". Records of the Dominion Museum 2: 145-146.

- ^ a b Ballance A. P. (1985) "Paryphanta at Pawakatutu". Tane 31: 13-18. PDF

- ^ a b (file created 20 October 2005) http://www.cites.org/eng/cop/10/prop/E-CoP10-P-10.pdf Archived 16 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine accessed 7 December 2009

- ^ Wildlife Act 1953. Schedule 7. Accessed 7 December 2009.

- ^ (2002) New Zealand Threat Classification System lists - 2002 - Terrestial (sic) invertebrate - part one. Department of Conservation, accessed 6 December 2009

- ^ Hitchmough R., Bull L. & Cromarty P. (2007) New Zealand Threat Classification System lists. Science & Technical Publishing, Department of Conservation, Wellington. 194 pp., ISBN 0-478-14128-9.

Further reading

- Coad N. (1998) "The kauri snail (Paryphanta busbyi busbyi), its ecology and the impact of introduced predators". MSc thesis, University of Auckland. 161 pp.

- Cox J. C. (1888) "Contributions to Conchology. No. I." Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 2(4): 1061-1064. Linnean Society of New South Wales. Plate XX, figure 6.

- Hutton F. W. (1880) Manual of the New Zealand Mollusca. A systematic and descriptive catalogue of the marine and land shells, and of the soft mollusks and Polyzoa of New Zealand and the adjacent islands. Wellington. Pages 21-22.

- Ohms P. G. (1948) "Some aspects of the anatomy of Paryphanta busbyi". MSc thesis, University of Auckland.

- Powell A. W. B. (1979) New Zealand Mollusca. William Collins Publishers Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand, ISBN 0-00-216906-1

- Spencer, H. G.; Brook, F. J.; Kennedy, M. (2006). "Phylogeography of Kauri Snails and their allies from Northland, New Zealand (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Rhytididae: Paryphantinae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 38 (3): 835–842. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.10.015. PMID 16503282.

External links

- http://www.doc.govt.nz/conservation/native-animals/invertebrates/kauri-snail/ Archived 5 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- http://bushmansfriend.blogspot.com/2007/07/kauri-snails-paryphanta-busbyi-mating.html

- photo of feeding

- photo of shells

- Paryphanta busbyi at National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)