Banat Republic

Banat Republic | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918–1919 | |||||||||||

|

Flag used during the Republic's proclamation | |||||||||||

| Anthem: Himnusz La Marseillaise | |||||||||||

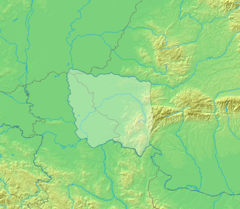

Claimed territory, superimposed over modern-day borders. | |||||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state Client state of the Hungarian Republic (1918) Client state of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (1918–1919) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Timișoara | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Customary: Austrian German, Hungarian, Swabian German Also spoken: Romanian, Serbian, Slovak, Rusyn, Croatian, French, Banat Bulgarian | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Banatian | ||||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||||

| Commissioner-in-Chief | |||||||||||

• 1918–1919 | Otto Roth | ||||||||||

| Legislature | People's Council | ||||||||||

| Historical era | World War I Revolutions and interventions in Hungary (1918–20) | ||||||||||

• Proclaimed | 31 October – 2 November 1918 | ||||||||||

• Government disbanded | 20 February 1919 | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1918 | 1,580,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Austro-Hungarian Krone | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

The Banat Republic (Template:Lang-de, Template:Lang-hu or Bánsági Köztársaság, Template:Lang-ro or Republica Banatului, Template:Lang-sr, Banatska republika) was a short-lived state proclaimed in Timișoara in November 1918, days after the dissolution of Austria-Hungary. The Republic claimed as its own the multi-ethnic territory of the Banat, in a bid to prevent its partition among competing nationalisms. Openly endorsed by the local communities of Hungarians, Swabians and Jews, the German-speaking socialist Otto Roth served as its nominal leader. This project was openly rejected from within by communities of Romanians and Serbs, who were centered in the eastern and western halves of the region, respectively. The short-lived entity was recognized only by the neighboring Hungarian Republic, with which it sought a merger. Its military structures were inherited from the Common Army, and placed under the command of a Hungarian officer, Albert Bartha.

The Republic advocated the establishment of a Swiss cantonal model in Eastern Europe, and favored peaceful cooperation among ethnicities, as alternatives to partition. It had limited control of the country outside of Timișoara: it never held Pančevo, which became the center of Serb self-government, and failed to fully control the Romanian cities of Lugoj and Caransebeș. Before the Hungarian armistice, the Banat was threatened with invasion by the French Danube Army. Roth's government also fought against a surge of peasant rebellions, and, though militarily weak, managed to quell uprisings in Denta, Făget and Cărpiniș.

In late November of 1918, the entire region was occupied by the Kingdom of Serbia, which in December became the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, or colloquially Yugoslavia. Roth remained in place as governor, and the Republic continued to have nominal existence. The following year, in January, the French ultimately intervened in the region, to prevent a clash between Yugoslavia and the Kingdom of Romania. The rump Republic was toppled on 20 February 1919, leading to significant violence. Roth escaped arrest and fled to Arad, where he was said to be in contact with the Hungarian Soviet Republic. He still proposed solutions for Banat's autonomy, including a plan to have the region absorbed into the French colonial empire. In 1920, the Banat was divided between Yugoslavia, Romania, and Regency Hungary.

Banat separatist and federalist schemes continued to be drafted during the early interwar, being especially popular with Swabians. Before 1921, the idea of an independent Banat was taken up by the Autonomous Swabian Party and by Swabians of French descent; Romanians such as Avram Imbroane and Petru Groza were sympathetic toward minority rights and decentralization, but did not endorse autonomy. As far-left militants, Groza and Roth collaborated with each other throughout the interwar period. Swabian-centered autonomist projects were also taken up by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the creation of a Nazified Banat; liberal Swabians such as Stefan Frecôt opposed this trend, and came to advocate full delimitation between French and German Swabians. After decades, separatist projects in the Banat reemerged in 2010s Romania, where they became associated with regional, rather than ethnic, identities.

Precedents

The Banat is a natural geographical region located on the left bank of the Danube, within the Pannonian plain and along the westernmost slope of the eponymous mountains. It was first organized into territorial units by the Angevin Hungarian Kingdom: the lowlands as counties, and the mountainous areas as a Banate of Severin. The latter coexisted with the somewhat informal jurisdictions of proto-Romanian knyazes and voivodes, some of which were still attested in the 1520s; these were only rarely represented in the "feudalized" Pannonian land.[1] Interwar journalist Cora Irineu proposes that an early instance of "autonomous policy" in the eastern Banat stemmed from the weakness of the Hungarian crown, which had difficulty defending itself against the Ottoman Empire during a long series of incursions.[2] Matthias Corvinus also organized the west into a separate "Captaincy", whose purpose was defend the border against the Turkish advances.[3]

From 1552, most areas now regarded as the Banat were absorbed into a single Ottoman administrative unit, named Eyalet of Temeşvar. Before 1568, the east was an autonomous Banate of Lugos, administered by the Transylvanian Principality before most of it was folded back into the Eyalet.[3] Upon emerging victorious in the Great Turkish War, the Habsburg Monarchy took over the region. In 1694, Serb settlers in the still-unnamed area obtained an imperial pledge granting them self-government, but this was never put into practice.[4] After the 1718 Treaty of Passarowitz, the region became a Habsburg province called the Banat of Temeswar. Hungarian geographer Sándor Kókai considers it an early predecessor to the Banat, rendering plausible the Republic's claim to territorial and cultural coherence.[5] According to the Serb medievalist Jovan Radonić, it is at this stage that the region acquired its name, as it had "never before been one administrative unit".[6]

This Banat was abolished in 1778, when its components were merged into the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary. In the 1790s, the Serbs became divided between those who pressed for a separate territory and those who, like Sava Tekelija, argued in favor of Josephine centralism. The project of reserving Banat for Serb self-government was ultimately rejected by Leopold II.[7] The status quo was challenged by the rise of Hungarian nationalism and liberalism. In 1834, mountainous eastern Banat hosted a Masonic Lodge which preached republicanism.[8] These ideas were at the forefront of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, which proclaimed independence for the entire Kingdom, maintaining its hold on the Banat. A pro-Hungarian Serb, Petar Čarnojević, was assigned Commissioner in the Banat, tasked with imposing martial law against conservative rebels.[9] In parallel, the concept of a Romanian Banat was being advanced by Romanian radicals. One of these was Eftimie Murgu, who organized a popular assembly in June and proclaimed a "Romanian Captaincy" within revolutionary Hungary. This effort was mainly directed against the Habsburg (Imperial Austrian) regime; the Austrians found regional backing from the rival government of "Serbian Vojvodina", which aimed to incorporate the entire Banat.[10]

Between 1849 and 1860, the Banat, together with the Bačka and Syrmia, was part of a new Habsburg–Serb province, the Voivodeship of Serbia and Banat of Temeschwar; the shared capital of all these entities was Timișoara. Seen as a "hybrid", this arrangement was not generally welcomed by Romanians.[11] However, a second experiment in Banatian autonomy was carried out after 1850, when the Austrians appointed Čarnojević's Aromanian son-in-law, Andrei Mocioni, as governor over the eastern half of the Voivodeship. This change was largely advantageous for the Romanian population, which controlled the administration, but ended in 1852, when Mocioni resigned over his conflicts with central government.[12] In November 1860, Mocioni organized a popular assembly, reissuing demands for a "Romanian Captaincy", but under Austrian supervision.[13] This action was not supported, and in December the region and the Voivodeship were folded back into the Kingdom of Hungary (or Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen). The Romanian focus shifted toward forming a separate crown land for the community, unifying the Banat with Transylvania and Bukovina.[14]

The "Captaincy" project was revived in part by a coalition of Serb and Romanian deputies in the Hungarian Diet, including Svetozar Miletić, Vincențiu Babeș, and Sigismund Popoviciu. During 1866, they proposed laws to redefine Hungary on the basis of ethnic federalism and corporatism.[15] However, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 cemented the Banat's annexation to the Lands of the Hungarian Crown, and kept the region under a unified government. This setback prompted Mocioni to withdraw from politics altogether.[16] Ethnic federalism was again redrawn in the 1900s by Aurel Popovici. However, his project, the "United States of Greater Austria", suggested the Banat's partitioning between a Romanian Transylvania and a rump Hungary, with a special status for Swabian-settled areas.[17]

History

Creation

The Banat issue was revisited during the final stage of World War I, with the collapse of Austro-Hungarian rule: the Aster Revolution toppled the Kingdom, and in mid November 1918 established a Hungarian Republic. In Timișoara, the anti-war protests that began in early October grew in extent and intensity towards the end of the month, with several statues representing Austrian authority toppled by the populace.[18] The Banat state was actually proclaimed during one such popular assembly, on 31 October or 2 November.[19] Lieutenant Colonel Albert Bartha, who was attempting to organize a Hungarian front against the advancing French Danube Army, claims that he created the Republic as a buffer zone; he also records 31 October as the Republic's official birth date.[20] Also that day, the Common Army split into National Committees representing the constituent nationalities. This was done by agreement between German Austria, still represented locally by Baron von Hordt, and the Hungarian National Council, represented by Alispán György Kórossy.[21]

Other accounts credit initiative to Otto Roth, a member of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party (MSZDP).[18][22] As reported by these, Roth, who had already served as Timișoara councilor, met with his party colleagues on 30 October, and afterward approached Bartha.[18] The process also involved local Freemasons, including two members of the Losonczy Lodge—Kálmán Jakobi and István Tőkés.[23]

Roth acknowledged that he spoke on that night at the Military Casino, where he did not proclaim the republic, but rather expressed his support for the concept. Instead, he announced that Bartha was in charge of the city's military command, and asked for a People's Council to be formed.[18][24] Romanian attendees opposed this move: their nominal leader, Aurel Cosma, also spoke on the occasion, and informed the other attendees that he and his peers would form national institutions of their own. Years later, Roth recalled being amazed that no Hungarian present moved to assassinate either him, for being a republican, or Cosma, for being a Romanian nationalist.[18][25]

The MSZDP local chapter organized the effort to create both the People's Council and subsequent Republican government, beginning with the large rally that had previously been announced in Timișoara's Liberty Square. The participants flew socialist red flags.[26] Eventually, an assembly of local politicians elected Roth "President of the Republic" and made Bartha, who was already head of the Military Council, commander of the Banat's military forces.[18][27] Accounts converge on noting that the Republic was proclaimed from the balcony of Timișoara City Hall.[18][28] The rally ended with renditions of Hungary's Himnusz and La Marseillaise.[29]

Also designated as Commissioner-in-Chief, Roth appointed sub-Commissioners in charge of the three traditional counties (Temes, Torontál, Krassó-Szörény).[30] Republican officials boasted that, by 4 November, they had already created a new administrative apparatus, as well as setting up a National Guard. The core of government was a 20-member Executive Committee, which proceeded to deal with the issues of supplies and famine.[31] On 3 November, the Republic and its confederation with Hungary earned support from another Swabian popular assembly, whose chief organizer was Kaspar Muth.[32] The state legislature was the same as the People's Council of Timișoara, and included 70 members from the local Civic Party and other "bourgeois parties", 60 from the national military committees, 40 from the Workers' Council, and the entire 20-member Timișoara city council.[33] According to the Romanian author Gheorghe Iancu, in terms of individual affiliation, the Council was dominated by the MSZDP.[34] As reported by Nova Zora newspaper of Vršac, this parliamentary body introduced tax brackets, forcing an individual tax of 400,000 Kronen on highest-income individuals.[35]

Though anti-Habsburg, Hungary's own republican regime, headed by Mihály Károlyi, sought to preserve as much as possible from the older Kingdom's territory, and to resist the advance of competing Romanian and Serb nationalisms within its borders. Although Hungarian troops withdrew from the area, Bartha was recognized as Károlyi's commissioner, and the Banat continued to be represented in Budapest by János (Johann) Junker.[34] While Roth's proclamation is sometimes rendered as a declaration of independence,[36] Republican officials openly acknowledged that their ultimate plan was to create a federal and democratic Hungary, with units modeled on the Swiss cantons.[37] A specific proposal for a Swabian "national canton" was advanced in December 1918 by Miksa Strobl.[38] Roth's polity is occasionally referred to as "Banat autonomous republic",[39] or as a "limited autonomy within the Magyar state".[18]

Croat scholar Ladislav Heka sees the Republic as resulting from an alliance between Hungarians and Swabians; he also notes that the Bunjevci, a Slavic Catholic community in neighboring Bačka, also preferred Hungarian rule to some extent.[40] Several Romanian and Serb historians agree that Hungarian designs were the main drivers behind the establishment of a Banat Republic, which they see as a proxy for Hungarian rule: "Mihály Károly's government desired a 'Banat autonomous republic' within a Magyar state [...], earning intense propaganda support from the Timișoara lawyer Otto Roth and from other Magyar, German and Jewish intellectuals."[41] Ion D. Suciu proposes that the republic was a "parody" and a "final diversion" in Károly's attempts to maintain control over the area.[42] According to Ljubivoje Cerović, "the leaders of the Banat Republic aimed primarily at ensuring Hungarian [territorial] integrity".[43] As noted by researcher Carmen Albert, the "so called 'Banatian republic'" remains a mysterious detail in regional history, but could be regarded as "essentially anti-union", in that it opposed Greater Romania.[44]

Internal conflicts

| History of Banat |

|---|

|

| Historical Banat |

|

| Modern Romanian Banat |

| Modern Serbian Banat |

| Modern Hungarian Banat |

According to estimates by Sándor Kókai, the Republic sought to cover "one of Europe's most complex areas".[45] The region was home to 1.58 million people; of them, 592,049 (37.42%) were Romanian, 387,545 (24.50%) were Swabian or other German, 284,329 (17.97%) were Serbs, and 242,152 (15.31%) Hungarian, with 4.8% belonging to "fourteen smaller ethnic groups". 855,852 (54.10%) belonged to the Eastern Orthodox churches, while 591,447 (37.38%) were Catholics.[46] Relying on similar data, historian Mircea Rusnac argues that the Republic could claim to represent some 47% of the population, namely those to whom the Serbs and Romanians afforded no say regarding the region's future.[18] Roth himself belonged to a minority: he was of Jewish origins, but did not practice Judaism.[18][47] His government was primarily backed by Hungarian and German workers, and found core support among the Swabian Catholic intellectuals.[31]

Roth's policies were contested from within the Republic's nominal territory by Cosma and the Romanian National Party (PNR), who proceeded to organize for Banat's merger into Greater Romania.[48] This caucus held its own rally in Liberty Square, demonstrating the numerical strength of its following and performing the Romanian nationalist anthem. Its importance was acknowledged by Roth, who recalled that "the streets trembled with the lockstep of [Cosma's] powerful guards".[49] The core events of Romanian resistance to the Republic closely followed the developments in Timișoara. After a meeting of the Romanians in Reșița on 31 October, a "National Council" and a self-defense force were created, co-opting some Romanian members of the MSZDP. This was later transformed into a "Workers' Council", presided upon by Petru Bârnau.[50] Meanwhile, Reșița's mostly German and Hungarian workers celebrated the Republic at a public rally on 1 November.[18]

On 3 November, Valeriu Braniște hosted at Lugoj a large assembly of Romanians, who validated Cosma's efforts and also voted for the creation of Romanian military units. These issues were again raised and endorsed at another assembly, held at Caransebeș on 7 November.[51] The city hall here was topped by the Romanian tricolor.[52] Hungarian presence disintegrated in eastern Banat, with leftover authorities complaining that Romanians had read the "People's Government policy" as authorizing secession in majority-Romanian localities.[53] However, Caransebeș continued to host two parallel Councils: a Republican one, created by Zsolt Réthy, and a Romanian one, under Remus Dobo.[54]

A Serb National Council had already been set up in Timișoara during the earliest days of the Republic. Presided upon by Svetozar Davidov and Georgije Letić, this assembly largely refused cooperation with Roth's Commissioners, only recognizing them as an ad-hoc city government; it demanded that Allied Powers occupy the Banat "as soon as possible".[55] On 5 November, Banat Serbs created another dissident National Council, at Pančevo.[31] On 10 November, the two Councils, alongside other Serb bodies, sent delegates to the Popular Assembly which voted for the Banat's immediate union with the Kingdom of Serbia.[56] However, Roth was able to create disunity between the Bunjevci and other Slavs: on 7 November, a "Bunjevac People's Republic" was proclaimed at Sombor as a close ally of the Banat Republic.[40]

According to his own recollections, Bartha began separate negotiations with the French, falsely claiming that he had 40,000 soldiers prepared to resist them. In reality, he acknowledged, there were less than 4,000.[57] His rivals Cosma and Lucian Georgevici had set themselves the goal of creating Romanian military units in each small locality; they reported 60,000 recruits in Temes alone.[58] However, all competing sides had limited control over rural areas: peasants and returnees from the Common Army took over control over the villages and established over 40 independent councils.[59] Already in October, the Timișoara Citizens' Guard, comprising paramilitaries of all nationalities, fought and defeated groups of liberated prisoners, restoring legitimate control over the Central Post Office.[60] Many Serbs who had been prisoners of war in Russia returned home with military training, social grievances, and communist beliefs. Known as "Octobrists", they joined up with deserters and outlaws ("green cadres") and began raiding in Clisura area.[61] Coriolan Băran, who took charge of the Romanian guards in Sânnicolau Mare, made note of a conflict opposing Romanians to the Banat Bulgarians of Stár Bišnov.[62]

A social revolt was sparked on 1 November, when the sugar mill of Margina, northeast of Lugoj, was taken over by peasants from the surrounding region; another nucleus was at Ciacova, south of Timișoara.[63] Former soldiers directed repression against the notaries public, identified as responsible for wartime injustice. Such incidents peaked at Ghilad, where one notary was tried and executed by a self-appointed court, and again at Denta, where the archive was devastated and its curator seriously injured.[64] The mayor of Bunya (now Făget) was murdered, and the schoolteacher and priest were chased out.[65] The rebel groups also organized looting against landowners of all nationalities—including attacks on the Mocioni family estate at Birchiș,[66] the Bissingen-Nippenburg residence in Vojvodinci,[67] and Géza Szalay's manor in Voiteg.[68]

In that context, Roth's Republic resorted to applying martial law.[43] Its National Guard attempted to repress the peasant movement, notably at Jebel, where 17 were killed in the confrontation.[68] Government remained largely powerless, but its task was taken up by loyalist troops from Timișoara. At Margina, they reportedly relied on 33 mercenaries employed by the sugar industry, who resorted to terrorizing the population.[69] On 4 November, loyalist units stormed into Denta and Cărpiniș, executing some tens of looters.[70] The same day, a Hungarian Guard intervened against anti-Jewish rioters in Făget, killing as many as 16 Romanians.[71] According to Romanian priest Traian Birăescu, the 3rd Honvéd Regiment, serving the Republic, committed wanton atrocities in Făget, Racovița, and Topolovățu Mare. He counts 160 victims of such incidents, between 3 and 17 November.[72]

During that same interval, the Republic's National Guard grew to incorporate the new arrivals, numbering at some 500 per district.[70] There were open clashes between these units and their Romanian counterparts: the occupation of Făget was only relieved when Axente Iancu and Dinu Popescu established and armed a Romanian Guard which ordered Republican troops to leave town.[73] Another enduring rebellion was that of Serb villagers in Kusić and Zlatica, who established their own "Soviet republic" with assistance from the "Octobrists".[43]

Serbian incursion

Following the Hungarian armistice, which allowed the Allied Powers to seize portions of Hungary, Bartha resigned in protest.[20] On 12 November,[74] the Royal Serbian Army entered the Banat with endorsements from both Hungary and the Allies. A force led by Colonel Čolović took control of Timișoara on 17 November,[18][72] being acclaimed by all communities as a guarantee of "freedom and democracy". Both Cosma and Roth spoke on the occasion, saluting the intervention; Roth greeted Čolović with the slogan "Long live internationalism!"[75] On 16–17 November, the National Guard of the Republic was disbanded,[18][70] and, according to Birăescu, "hundreds of Romanian peasants" were set free from Republican jails.[72] Roth was technically confirmed as civilian governor, and the People's Council remained in place as a regional legislature.[18][76] Government instructed the Banat's citizens to remain calm when interacting with the intruders, and from 16 November "existed only on paper".[77]

By 20 November, Serbian forces had camped along the Mureș River, from Szeged to Lipova.[78] In their advance eastwards, they stopped at Caransebeș and Orșova.[79] Serbian garrisons disarmed the surviving Guards of Timișoara and Reșița, while forcing the two Lugoj Councils to establish a single Guard unit.[80] The "Octobrist" republic of Kusić–Zlatica, whose leaders had attempted a march on Bela Crkva, was also repressed during the interval.[43]

The general purpose of this offensive was to secure as much of the region as possible before the Paris Peace Conference, obtaining the most favorable terms for the region's split between Serbia and Romania.[81] Serbia regarded the Banat under its control as an acquired territory, part of a province called Banat, Bačka and Baranja. On 25 November, this view was enforced by the all-Slav Popular Assembly of Novi Sad. It hosted 72 Serb, Bunjevci, Slovak, Montenegrin, Šokci and Krashovani deputies from throughout the disputed areas.[82] Non-Slavs were excluded on principle, though not entirely absent—with the exception of Romanians, who boycotted this rally.[83]

Some Romanians were by then driven out by the Serbian intervention. They include Băran, who began organizing Banatian guards from Transylvania,[62] as well as Caius Brediceanu and Ioan Sârbu, who asked for the French to step in as peacekeepers.[84] Romanian peasants were originally sympathetic to the Serbian administration, as Serbia and Romania were both in the Allied camp. However, requisitions, overhunting, abuse against property owners, and conflicts over the reemergence of Hungarian Gendarmes sparked a number of conflicts between the occupied and occupiers.[85] Also on 12 November, the local Romanian community aligned itself with the Central Romanian National Council (CNRC) of Transylvania, which was becoming the main ethnic representation body. Iosif Renoi, a Romanian member of the MSZDP and a resident of Bocșa, was elected on the CNRC leadership board.[86]

During November, together with the other Council delegates and a number of sympathetic Swabians, Banat Romanians participated in negotiations with Károly's representative, Oszkár Jászi. The CNRC issued demands for the whole territory of the Banat Republic to be annexed by Romania, alongside the counties of Csanád and Békés; Jászi replied with promises of cantonal federalism within a "new democratic country".[87] Talks were suspended without a resolution, prompting the CNRC to call for a Romanian national assembly at Alba Iulia, Transylvania, on 1 December.[88] To avoid antagonizing the Serbian administration, elections for the assembly were not held in the Banat, which was advised to send only informal representatives "from all social classes".[89] Some 182 of these were present for the vote, despite the Serbian Army's attempts to block access.[90] Another 200, however, were arrested before departure, then deported to Serbia[91] or to occupied Albania.[92] The delegates held coordination meetings which voted against autonomy for the Banat and also called for French or English troops to take over administration.[93]

On 1 December, remembered as the "Great Union Day", the Alba Iulia Assembly proclaimed the Transylvanian–Banatian merger with Romania; at the same time Serbia merged into a Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (commonly known as Yugoslavia). This polarization also divided the Swabian voters, between those who favored the Romanian option and those who acted in favor of a Yugoslavian project. The pro-Romanian lobby was enforced by Transylvanian Saxons, in particular the writer Viktor Orendi-Hommenau.[94] The latter had established a Swabian cultural and political club, Kultur der Schwaben.[95] In parallel, Kaspar Muth continued to press for an autonomous republic, and, in January 1919, set up the Autonomous Swabian Party.[96]

Clampdown

A small French presence in the Banat had been established in parallel with the Serbian occupation: French and African patrols, coordinated by François Léon Jouinot-Gambetta, were stationed just outside Timișoara, and in places such as Igriș and Vojvodinci.[67] On 3 December, after tensions between Romania and Yugoslavia had escalated and threatened to erupt into a regional war, 15,000 French troops answering to Generals Paul Prosper Henrys and Henri Berthelot occupied Timișoara.[97] On 18 December, the Swabians' German National Council reemerged and openly asked for its own military self-defense units, or Volksmiliz. These were to be directly modeled on the Swiss Armed Forces.[98] Romanian community leaders and Orendi-Hommenau's followers celebrated the French intervention, but, by January, came to fear that France was tolerating another buildup of Yugoslavian forces.[99] Jouinot-Gambetta, who was assigned command over the French troops in the Republican capital, came to be disliked by the Romanian community there, being widely perceived as a Hungarophile; by contrast, local Magyars experienced a surge of Francophile sentiment.[100]

Berthelot was finally persuaded by the Romanians to demand that most Yugoslav troops withdraw from the central and eastern portions of the Banat.[101] On 25 January, Léon Gaston Jean-Baptiste Farret and the 11th Colonial Infantry Division were in charge of Krassó-Szörény.[102] By 27 January, French soldiers had full control over the eastern Banat, establishing a buffer zone centered on Timișoara. Roth preserved power, having been reconfirmed by Jouinot-Gambetta.[103] The city was not entirely relinquished by the Yugoslav side. In parallel to the French advance, the new Royal Yugoslav Army, under General Grujić, consolidated a presence in Timișoara.[104]

By then, the rump Republic and the Serb Council had become foes. The Council's newspaper, Srpski Glasnik, commented that Roth was a "chameleon" in politics, bringing up evidence that he was plotting a pro-Hungarian coup.[105] On 20 February, the German National Council and the remaining executive institutions of the Republic were dissolved. One version of the events credits the French with having taken this decision.[106] Another account informs that the Yugoslav contingent in Timișoara was behind the move, and mentions that fighting occurred between the Serbs and the Republican National Guard.[107] Timișoara's commander was by then the Swabian Josef Geml, who refused to recognize Yugoslavian rule from Novi Sad, leaving the city exposed to threats of a retaliatory blockade.[103]

On 21 February, in territories they still controlled, Yugoslav commanders began replacing the Republican bureaucracy with their co-nationals.[18][108] From the Yugoslav point of view, Roth's replacement was Martin Filipon, who was both Timișoara's Mayor and the regional Župan.[109] In his sectors, Berthelot allowed Hungarian civilian administrators to resume their work for the duration of French rule, and proceeded to ban all other national councils, as well as displays of nationalist flags.[110] The Károlyi government attempted one final time to reassert control over the region in appointing an Alispán for Krassó-Szörény. Following Romanian protests, this move was vetoed by the French.[111]

Protests and strikes followed soon after Roth's toppling from power.[18][105] Timișoara's German and Hungarian workers asked the French to intervene against the consolidation of a "Serbian empire" and to preserve the armistice agreement.[105] Pursued by the Yugoslavs, Roth found refuge with the French garrison in Arad.[18] The following period restructured Swabian political camps: Muth's initial option for Hungary was widely discredited when, in March, Károlyi fell from power and a Hungarian Soviet Republic was established.[96] Meanwhile, Reinhold Heegen, replacing Filipon as Serbian-appointed Mayor of Timișoara, began campaigning with some success for the Banat to join Yugoslavia, and promised that Swabians would own a university of their own.[112] While Muth himself switched to the Yugoslavian plan, most of his colleagues became supporters of Greater Romania.[96]

Roth allegedly aligned himself with the Hungarian Soviets,[113] although, by his own account, he was their ideological enemy.[114] He also introduced another political solution, presented by him in direct talks with French officials: he proposed an "independent Banat under French protection", and suggested its subsequent inclusion into the French colonial empire.[115] The French Ambassador in Yugoslavia, Louis Gabriel de Fontenay, rejected the plan altogether, and in particular its claim that Romanians also favored independence.[116] However, as recorded by Berthelot himself, the prospect of sustaining Banatian republicanism was still advocated in April 1919 by Paul-Joseph de Lobit, who commanded over the French Army of Hungary.[117] In the meantime, Swabian delegations presented Berthelot with a request for union with Romania; this was formally endorsed on 15 April, when all Swabian group leaders met in Timișoara.[110] On the Romanian side, a new version of Banatian regionalism was reemerging from nationalist groups opposed to the PNR: in mid 1919, a National Union from Banat, led by Avram Imbroane and Petru Groza, rallied support for that cause.[118] Its manifestos demanded decentralization and minority rights, but without full autonomy.[119]

Legacy

Greater Romania

In late May 1919, units of the Romanian Land Forces moved in from Transylvania, and were garrisoned alongside the French in Lugoj. That city was allowed to fly the Romanian tricolor.[120] As reported by Émile Henriot, Timișoara Swabians were generally in favor of this development, though a minority supported independence for the Banat and Bačka as a federal state. Their faction preferred incorporation into Hungary, but viewed emancipation as a next-best solution. Such groups also referenced the Swiss model, but did not want French tutelage; they preferred an American occupation.[91] During the remaining months of French occupation, however, various Republican officials were again employed by the administration. In autumn 1919, Tőkés of the Losonczy Lodge became Alispán of Temes.[121]

The project of making the Banat into an independent buffer state was aired in early 1919 by George D. Herron, an American socialist and pacifist. French diplomats gave some support to Herron's designs, a matter which aggravated Franco–Romanian relations.[122] On 16 April 1920, Swabian activists submitted to the Peace Conference another failed proposal for Banatian–Bačkan independence, specifically referencing the Swiss cantonal model.[5][18] The "neutral and independent republic of Banatia" was mostly embraced by Swabians of French (Lorrain) descent, who also proposed a separate canton for their subgroup.[123] By then, however, the Franco-Swabian Stefan Frecôt had joined efforts with Michael Kausch and created a "German–Swabian People's Party" (DSVP), which competed with Muth's Autonomous Swabian Party.[124] Muth and Imbroane both won seats in Romania's Lower Chamber during the race of May 1920. Both deputies spoke out against the planned partition of the Banat, though Muth also pressed for the Swabians to have cultural autonomy as described by the Minority Treaties.[125]

The Banat frontier was largely settled under the Treaty of Trianon of June 1920. The area was effectively partitioned between Yugoslavia and Romania during July, though there were still border adjustments to 1924.[126] During that interval, the Bunjevac-Šokac Party began advocating autonomy for the Bunjevci and other Catholics, including for areas of the Yugoslav Banat.[127] Only a small portion in the region's northwest was incorporated by the reconstructed Hungarian Kingdom, a state which also hosted 145,000 refugees from other parts of the Banat.[128] For seven days in August 1921, this Banatian extremity was annexed to the Serbian-Hungarian Baranya-Baja Republic, which was in part a sample of Bunjevci separatism.[129]

On 10 August 1920, one week after a Romanian takeover in Timișoara,[130] thirty-three Swabian communes voted to support the annexation.[131] A final delegation, chaired by Frecôt and claiming to represent 68% of the whole Banat population,[132] petitioned the Allies with a more ambitious project. It wanted the entire region merged into Romania, but this proposal was not followed through.[133] In parallel, the DSVP and the Autonomist Party dissolved into the German Party, which had reconciled with Romanian centralism and was acting as a shared caucus for all Germans of Romania; the German National Council was renamed Community of the German Swabians, and survived as such to 1943.[134]

Roth was arrested by the Romanian authorities and released in 1920, reportedly promising to keep out of politics. He focused on his photographic studio and his contribution to the Timișoara Chamber of Labor.[135] In the 1930s and '40s, Roth discreetly aligned himself with Groza, rekindling Banatian regionalism within the far-left Ploughmen's Front.[136] For a while in the 1920s, full regional self-determination "to the point of separation" was also endorsed by the illegal Communist Party of Romania, which followed guidelines set by the Comintern.[137] Its 1928 Resolution on the National Issue specifically referred to the Banat as a victim of Romanian "imperialism".[138]

More mainstream support for regionalism was promoted from within the People's Party by Imbroane's brother Nicolae, who in 1926 established a distinct parliamentary club.[139] Divided into counties (Caraș, Severin, Timiș-Torontal), the region was given some political representation with the establishment of a short-lived Ministerial Directorate for Romania's south-west; full regionalism was regarded as in breach of the 1923 Constitution.[140] This status quo was challenged by Romulus Boilă of the National Peasants' Party, who proposed dividing Romania into autonomous entities—though his project was never popular with the electorate.[141] The Banat was reestablished as a single "land" in 1938–1940, taking the name of Ținutul Timiș. The new structure also annexed non-Banatian areas, namely Hunedoara County and the northern communes of Severin.[142] The reform was sanctioned by a dictatorial National Renaissance Front, with Alexandru Marta assigned as Royal Commissioner; his tenure only strengthened centralization.[143]

Later echoes

During World War II, Nazi Germany involved itself in endorsing regional government for the Swabians. In Romania, it promoted Swabian identity as a Nazi construct, prompting a major split between the Swabians-proper and descendants of the Banat French; the latter were led by Frecôt.[144] In November 1940, under a friendly National Legionary State, Germany obtained the creation of an autonomous organism, or "German Ethnic Group", which was entirely Nazified.[145] This arrangement was maintained under Germany's subsequent ally, Ion Antonescu, though the Ethnic Group itself came to be secretly monitored by the Gendarmes. These sources reported back that Germany intended to carve out a "Danube Land" for the Swabians.[146] The Nazi autonomist policy was being pursued more expansively in occupied Serbia. In 1941, Romania and Hungary vied with each other for being granted control of the region by Germany;[147] eventually, a Banat administrative unit was created out of the former Yugoslav partition.[5]

At the height of Antonescu's dictatorship, Groza was placed under arrest for his involvement with the antifascist Union of Patriots; Roth himself was able to organize an effort to free Groza.[148] He was nevertheless submitted to the racial legislation for the remainder of the war, during which time he contemplated exiling himself and all other Jewish Banatians to Madagascar.[18][149] Following the King Michael Coup of August 1944, Serb partisan units experimented with self-government in the Clisura area, setting up a Council led by Triša Kojičić.[150]

Around November, Roth himself made a brief return to the Banat administration, representing the Social Democratic Party chapter in Timiș-Torontal.[151] This group also hosted his political rival of 1918, Petru Bârnau, who was by then mayor of Reșița.[152] During the subsequent interval, much of the Swabian population was lost, as a number left as refugees along with the retreating German army, while many of the ones left were the target post-war expulsions. In the easternmost counties, some 7,000 Swabians were deported as labor conscripts in the Soviet Union.[153] Although many refugees and deportees were accepted in West Germany, 10,000 of those identified as French, having left the Banat by 1945, were relocated to France.[154] In Caraș, the Social Democrats clashed with the Soviet occupation forces, demanding that they end their anti-German abuse.[152] Groza, by then the Prime Minister of Romania, favored a degree of segregation between the Romanians and Swabians, but praised the latter for their socialist traditions, and proposed to have them merge into the urban proletariat.[155]

Soviet presence peaked with the establishment of a Romanian communist state in 1948. During its early stages, this new regime redesigned the administrative map, and by 1952 had re-amalgamated the Romanian Banat into Regiunea Timișoara. From 1956, the unit was extended northwards, incorporating parts of Arad Region.[156] The advent of Romanian national communism in 1960 was initially signaled by the renaming of territorial units with their more traditional form: the creation of Regiunea Banat was welcomed as a sign of "re-Romanianization"[157] and "partial return to the traditional forms of administrative organization".[158] Within eight years, the larger units were folded back into counties by the national-communist leader, Nicolae Ceaușescu.[159] The nationalist drive later came with renewed suspicion toward autonomy movements, and toned down internationalism. In 1972, an article by C. Mîcu, which contained some praise of the 1918 Republic, was mistakenly published by the Union of Communist Youth, prompting the intervention of official censors.[160]

Writing in samizdat form during the 1980s, philosopher Ion Dezideriu Sîrbu argued that repression and "darkness" were prompting the provinces back into autonomist stances. As he noted, the Banat and other regions needed to be devolved by a Romanian "perestroika".[161] The anti-communist Revolution of 1989, which began in Timișoara, reignited controversies about autonomy and separatism. Before his toppling and execution, Ceaușescu accused the revolutionaries of wanting to separate Transylvania and the Banat from Romania.[162] This charge was again proffered in disputes between the post-communist National Salvation Front and its opponents. Members of the former spuriously claimed that the latter's Proclamation of Timișoara was about regional autonomy.[162][163]

During the Ceaușescu era, the Swabian exodus had been accelerated, as the regime had agreed to provide exit visas for tens of thousands of Romanian Germans in exchange for hard currency.[164] Especially after the Revolution, Banatian autonomy or independence were again taken up as causes—in this instance, by various members of the Romanian majority in the eastern Banat. These groups, flying a white cross on green as their flag, became interested in recovering the region's Habsburg heritage, and in some cases declared themselves ethnically distinct from other Romanians.[165] In 2013, activists from this movement endorsed both regional independence and European federalism.[166] The green flag became popular as a sign of regional affiliation, and was prominently displayed during the anti-government rallies of 2014. This issue was highlighted by the pro-government Social Democrats, who saw it as a move toward autonomy or independence; that claim was denied by members of the Banat League.[162]

Notes

- ^ Ștefan Pascu, "O impresionantă lume a obștii românești (IV)", in Magazin Istoric, August 1986, pp. 31–32

- ^ Cora Irineu, "Scrisori bănățene", in Adriana Babeţi, Cornel Ungureanu (eds), Europa Centrală. Memorie, paradis, apocalipsă, p. 177. Iași: Polirom, 1998. ISBN 973-683-131-0

- ^ a b Radonitch, p. 2

- ^ Cerović, p. 51

- ^ a b c Kókai, p. 74

- ^ Radonitch, pp. 1, 3

- ^ Cerović, pp. 75–79. See also Radonitch, p. 7

- ^ Kakucs (2016), p. 476

- ^ Cerović, pp. 86–87

- ^ Albert, p. 450; Gh. Cotoșman, "Eftimie Murgu și Banatul la 15/27 Iunie 1848.—Aniversarea a 99 de ani de la istorica Adunare Națională din Lugoj", in Foaia Diecezană, Vol. LXII, Issues 28–29, July 1947, pp. 1–5. See also Cerović, pp. 87–91

- ^ Albert, p. 450

- ^ Adrian Dehleanu, "Familia Mocioni. Istoria uneia dintre cele mai vechi familii nobiliare din istoria românilor", in Țara Bârsei, Vol. XIV, Issue 14, 2015, p. 220

- ^ Milin, p. 21; Tiron, p. 30

- ^ Vicențiu Bugariu, "Andrei Mocsonyi de Foeni", in Societatea de Mâine, Nr. 20/1931, pp. 399–400

- ^ Milin, pp. 21–28

- ^ Tiron, pp. 30–31

- ^ Aurel Popovici, Stat și națiune. Statele-Unite ale Austriei-Mari. Studii politice în vederea rezolvării problemei naționale și a crizelor, pp. 236, 281–282. Bucharest: Fundația pentru Literatură și Artă Regele Carol II, 1939. OCLC 28742413

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s (in Romanian) Ștefan Both, "Povestea Republicii Bănățene, forma statală care a supraviețuit patru luni. A fost proclamată de un avocat evreu la sfârșitul Primului Război Mondial", in Adevărul (Timișoara edition), 5 November 2017

- ^ Kókai, pp. 67–68

- ^ a b Kókai, p. 67

- ^ Dudaș & Grunețeanu, p. 137

- ^ Dudaș & Grunețeanu, pp. 137–139; Kókai, pp. 67–68

- ^ Kakucs (2016), pp. 483, 484

- ^ Dudaș & Grunețeanu, p. 137. See also Birăescu, p. 184

- ^ Dudaș & Grunețeanu, pp. 137–138

- ^ Dudaș & Grunețeanu, pp. 139–140

- ^ Kókai, pp. 67–68. See also Dudaș & Grunețeanu, p. 139

- ^ Dudaș & Grunețeanu, p. 139; Kókai, pp. 67–68

- ^ Dudaș & Grunețeanu, p. 139

- ^ Suciu, pp. 1092, 1102. See also Dudaș, p. 359

- ^ a b c Kókai, p. 68

- ^ Buruleanu & Păun, pp. 48–49

- ^ Kókai, pp. 63, 68

- ^ a b Iancu, p. 62

- ^ "Republica bănățeană", in Glasul Cerbiciei, Vol. III, Issue 4, 2009, p. 9

- ^ Cerović, p. 151; Minahan, p. 64

- ^ Heka, pp. 114–115, 126; Kókai, p. 68

- ^ Heka, pp. 114–115

- ^ Buruleanu & Păun, p. 48; Iancu, p. 62; Kakucs (2014), p. 365

- ^ a b Heka, p. 126

- ^ Buruleanu & Păun, p. 48

- ^ Suciu, pp. 1091–1092, 1102

- ^ a b c d Cerović, p. 151

- ^ Albert, p. 449

- ^ Kókai, p. 64

- ^ Kókai, pp. 64–66

- ^ Brînzeu, pp. 69, 229

- ^ Buruleanu & Păun, p. 48; Dudaș & Grunețeanu, pp. 137–141; Suciu, p. 1092

- ^ Dudaș & Grunețeanu, p. 141

- ^ Suciu, p. 1096

- ^ Dudaș & Grunețeanu, pp. 135–136, 143–145; Suciu, pp. 1092–1095

- ^ Dudaș & Grunețeanu, pp. 135–136

- ^ Tomoni, p. 292

- ^ Kakucs (2014), p. 352

- ^ Cerović, pp. 152–153

- ^ Cerović, p. 153; Heka, p. 115

- ^ Kókai, p. 67. See also Heka, pp. 125–126

- ^ Dudaș & Grunețeanu, pp. 140–147

- ^ Kakucs (2014), p. 352; Suciu, p. 1097

- ^ Kakucs (2014), p. 365

- ^ Cerović, pp. 150–151

- ^ a b Dudaș & Grunețeanu, p. 143

- ^ Suciu, pp. 1097–1098. See also Tomoni, pp. 291, 293, 297–299

- ^ Büchl, pp. 252, 253

- ^ Tomoni, p. 291

- ^ Suciu, p. 1097

- ^ a b Moscovici, p. 243

- ^ a b Büchl, p. 252

- ^ Tomoni, pp. 293, 297–299

- ^ a b c Büchl, p. 253

- ^ Tomoni, pp. 291–292

- ^ a b c Birăescu, p. 185

- ^ Tomoni, pp. 293, 294

- ^ Buruleanu & Păun, p. 48; Dudaș, p. 359; Suciu, p. 1101. See also Kókai, p. 68

- ^ Cerović, pp. 154–155

- ^ Moscovici, pp. 242–243

- ^ Kókai, pp. 68, 69

- ^ Dudaș, p. 359; Kókai, pp. 68–69; Moscovici, p. 242; Suciu, p. 1101

- ^ Moscovici, p. 242

- ^ Kakucs (2014), pp. 352, 357, 365. See also Dudaș & Grunețeanu, pp. 143, 146–147

- ^ Buruleanu & Păun, p. 49; Kókai, pp. 69–71; Moscovici, p. 242

- ^ Cerović, pp. 155–156, 157–158

- ^ Heka, p. 116

- ^ Moscovici, p. 245; Suciu, p. 1101

- ^ Albert, pp. 451–456

- ^ Suciu, pp. 1095–1097

- ^ Kókai, pp. 70–71. See also Heka, pp. 126–127

- ^ Buruleanu & Păun, p. 49

- ^ Suciu, p. 1099

- ^ Buruleanu & Păun, pp. 51–52. See also Albert, p. 452; Dudaș, p. 359; Moscovici, pp. 242–243, 245; Suciu, pp. 1099–1101; Tomoni, pp. 294–296

- ^ a b Émile Henriot, "Dans le Banat. Le vœu des nationalités et la querelle serbo–roumaine", in Le Temps, 30 May 1919, p. 2

- ^ Albert, p. 452; Birăescu, p. 185

- ^ Moscovici, p. 245; Suciu, p. 1099–1100

- ^ Moscovici, p. 245; Suciu, p. 1103

- ^ Moscovici, p. 245

- ^ a b c Buruleanu & Păun, p. 51

- ^ Kókai, pp. 69, 72

- ^ Kakucs (2014), pp. 347–348

- ^ Moscovici, pp. 245–246

- ^ Moscovici, pp. 243–244

- ^ Moscovici, pp. 246–249

- ^ Moscovici, p. 248

- ^ a b Pițigoi, p. 11

- ^ Moscovici, p. 249

- ^ a b c Cerović, p. 157

- ^ Suciu, pp. 1101–1102

- ^ Kókai, p. 72. See also Iancu, p. 62; Moscovici, p. 249

- ^ Cerović, pp. 151, 155–157; Iancu, pp. 62–63; Moscovici, p. 249

- ^ Cerović, pp. 156–157

- ^ a b Suciu, p. 1103

- ^ Suciu, p. 1102

- ^ Kókai, p. 72

- ^ Kókai, p. 73

- ^ Brînzeu, p. 76

- ^ Suciu, p. 1102. See also Kókai, p. 73

- ^ Suciu, pp. 1102–1103

- ^ Laurențiu-Ștefan Szemkovics, "Note zilnice ale generalului Berthelot privitoare la Consiliul Național Român de la Arad, la Transilvania, la Banat și la transilvăneni (26 noiembrie 1918–5 mai 1919)", in Analele Aradului, Vol. V, Issue 5 (Supplement: Asociația Națională Arădeanăpentru cultura poporului român), 2019, p. 393

- ^ Marin Pop, "Activitatea organizației Partidului Național Român din județul Timiș în primii ani după Marea Unire (1919–1920)", in Arheovest I. Interdisciplinaritate în Arheologie și Istorie, p. 926. Szeged: JATEPress Kiadó, 2013. ISBN 978-963-315-153-2

- ^ (in Romanian) Florin Bengean, "Preotul Avram Imbroane, un cleric luptător pentru unitatea națională a poporului român", in Cuvântul Liber, 26 June 2015

- ^ Suciu, p. 1104

- ^ Kakucs (2016), p. 484

- ^ Pițigoi, p. 14

- ^ Vultur, p. 19

- ^ Panu, p. 124. See also Narai (2008), pp. 311–312

- ^ Alexandru Porțeanu, "The Higher Raison D'Etat and the Supreme Imperative of World Peace, as Decisive Factors for All Signatories of the Treaty of Trianon (1920–1921) in Its Final Stages. The Treaty Ratification by Romania", in HyperCultura. Biannual Journal of the Department of Letters and Foreign Languages, Hyperion University, Vol. 3, Issue 2, 2014, pp. 4–5

- ^ Buruleanu & Păun, p. 51; Cerović, pp. 159–160

- ^ Heka, p. 130

- ^ Heka, p. 128

- ^ Heka, pp. 128–137

- ^ Cerović, p. 159; Iancu, p. 66

- ^ Buruleanu & Păun, p. 51. See also Dudaș, pp. 360–361

- ^ Dudaș, pp. 360–361

- ^ Buruleanu & Păun, p. 51; Dudaș, pp. 360–361; Vultur, pp. 45–48

- ^ Panu, pp. 119, 124–125. See also Narai (2008), pp. 312–314

- ^ Brînzeu, pp. 68–69, 126

- ^ Brînzeu, pp. 64, 67–69, 94, 137, 140–143, 229, 391

- ^ Cioroianu, pp. 21, 35, 39–41; Cojoc, passim

- ^ Cojoc, p. 52

- ^ "Știrile săptămânii. Un bloc al deputaților bănățeni", in Lumina Satelor, Issue 28, July 1926, p. 5

- ^ Colta et al., pp. 74–75

- ^ (in Romanian) Dragoș Sdrobiș, "Trecutul ne este o țară vecină", in Cultura, Issue 332, July 2011

- ^ Colta et al., pp. 75, 222–223

- ^ Florin Grecu, "Centralizare versus 'descentralizare'. 'Reforma administrativă' de la 1938", in Polis. Revistă de Științe Politice, Vol. II, Issue 1, December 2013–February 2014, pp. 15–34. See also Colta et al., pp. 222–223

- ^ Dudaș, pp. 361–363; Vultur, pp. 15–16, 19, 45–52

- ^ Dudaș, p. 362; Narai (2008), pp. 314–315; Vultur, p. 19

- ^ Dușan Baiski, "Război în Banat", in Morisena. Revistă Trimestrială de Istorie, Vol. II, Issue 3, 2017, pp. 33–34, 40; Narai (2008), pp. 314–315

- ^ Ottomar Trașcă, "Relațiile româno–ungare în rapoartele lui Raoul Bossy", in Magazin Istoric, October 2020, pp. 25–29

- ^ Brînzeu, 501–502, 505

- ^ Brînzeu, 291, 307

- ^ Cerović, p. 163

- ^ Radu Păiușan, "Activitatea Uniunii Patrioților în Banat în anul 1944", in Analele Banatului. Arheologie—Istorie, Vol. XVIII, 2010, p. 298

- ^ a b Eusebiu Narai, "Activitatea Partidului Social-Democrat din judeţele Caraș și Severin în anii 1944–1948", in Arheovest I. Interdisciplinaritate în Arheologie și Istorie, p. 969. Szeged: JATEPress Kiadó, 2013. ISBN 978-963-315-153-2

- ^ Narai (2008), pp. 327–329

- ^ Vultur, pp. 12–14, 17–18

- ^ Narai (2008), p. 318

- ^ Colta et al., p. 76

- ^ Cioroianu, pp. 217–218

- ^ Colta et al., pp. 76–77

- ^ Buruleanu & Păun, p. 73; Colta et al., p. 77

- ^ Ion Zainea, "Aspecte din activitatea cenzurii comuniste: controlul producției de carte social-politică. Tendințe și fenomene semnalate în cursul anului 1972", in Crisia, Vol. 41, Issue 1, 2011, p. 339

- ^ Ion Dezideriu Sîrbu, "Exerciții de luciditate", in Adriana Babeţi, Cornel Ungureanu (eds), Europa Centrală. Memorie, paradis, apocalipsă, pp. 155–156. Iași: Polirom, 1998. ISBN 973-683-131-0

- ^ a b c (in Romanian) Ștefan Both, "Separatismul bănățean: de la teama lui Ceaușescu și frica lui Ion Iliescu la agitatorii lui Victor Ponta", in Adevărul (Timișoara edition), 10 November 2014

- ^ (in Romanian) Ruxandra Cesereanu, "Proclamația de la Timișoara si legea lustrației", in Revista 22, Issue 782, March 2005

- ^ (in Romanian) Ștefan Both, "Mărturiile șvabilor vânduți de Ceaușescu Germaniei. Cât era șpaga cerută de securiști și ce a făcut fostul dictator cu miliardele de mărci", in Adevărul (Timișoara edition), 12 June 2014; Cioroianu, pp. 473–474

- ^ Minahan, pp. 63–64

- ^ Minahan, p. 64

References

- Carmen Albert, "Ocupația sârbă din Banat în memorialistica bănățeană", in Analele Banatului. Arheologie—Istorie, Vol. XIX, 2011, pp. 449–456.

- Traian Birăescu, "Scrisori din Timișoara", in Cele Trei Crișuri, Vol. IX, November–December 1928, pp. 184–185.

- Nicolae Brînzeu, Jurnalul unui preot bătrân. Timișoara: Eurostampa, 2011. ISBN 978-606-569-311-1

- Anton Büchl, "Soziale Bewegungen in der Banater Ortschaft Detta 1875–1921", in Ungarn-Jahrbuch, Vol. VIII, 2000, pp. 223–254.

- Dan N. Buruleanu, Liana N. Păun, Moravița. Album monografic. Timișoara: Editura Solness, 2011.

- Ljubivoje Cerović, Sârbii din România. Din Evul mediu timpuriu până în zilele noastre. Timișoara: Union of Serbs of Romania, 2005. ISBN 973-98657-9-2

- Adrian Cioroianu, Pe umerii lui Marx. O introducere în istoria comunismului românesc. Bucharest: Editura Curtea Veche, 2005. ISBN 973-669-175-6

- Mariana Cojoc, "Cadrilaterul și 'Dobrogea Veche' în propaganda comunistă interbelică. 'Autodeterminare până la despărțirea de statul român'", in Dosarele Istoriei, Vol. VII, Issue 1 (65), 2002, pp. 50–54.

- Rodica Colta, Doru Sinaci, Ioan Traia, Căprioara: monografie. Arad: Editura Mirador, 2011. ISBN 978-973-164-096-9

- Vasile Dudaș, "Ștefan Frecot", in Analele Banatului. Arheologie—Istorie, Vol. XVI, 2008, pp. 359–363.

- Vasile Dudaș, Lazăr Grunețeanu, "Contribuția avocaților bănățeni la activitatea consiliilor și gărzilor naționale românești în toamna anului 1918", in Studii de Știință și Cultură, Supplement: Colocviul Internațional Europa: Centru și margine. Cooperare culturală transfrontalieră, Ediția a VI-a, 19–20 octombrie 2017, Arad – România, 2017, pp. 131–148.

- Ladislav Heka, "Posljedice Prvoga svjetskog rata: samoproglašene 'države' na području Ugarske", in Godišnjak za Znanstvena Istraživanja, 2014, pp. 113–170.

- Gheorghe Iancu, Justiție românească în Transilvania (1919). Cluj-Napoca: Editura Ecumenica Press & George Bariț Institute, 2006. ISBN 973-88038-1-0

- Lajos Kakucs,

- "Gărzile civice și societățile de tir din Banat între anii 1717–1919", in Analele Banatului. Arheologie—Istorie, Vol. XXII, 2014, pp. 339–381.

- "Contribuții la istoria francmasoneriei din Banat", in Analele Banatului. Arheologie—Istorie, Vol. XXIV, 2016, pp. 467–494.

- Sándor Kókai, "Illúziók és csalódások: a Bánsági Köztársaság", in Közép-Európai Közlemények, Vol. 2, Issues 2–3, 2009, pp. 63–74.

- Miodrag Milin, "Colaborarea româno–sârbă în chestiunea națională din monarhia dualistă", in Vasile Ciobanu, Sorin Radu (eds.), Partide politice și minorități naționale din România în secolul XX, Vol. V, pp. 20–30. Sibiu: TechnoMedia, 2010. ISBN 978-606-8030-84-5

- James Minahan, Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations. Ethnic and National Groups around the World. Santa Barbara & Denver: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016. ISBN 978-1-61069-953-2

- Ionela Moscovici, "Banatul în așteptarea păcii. Premisele unei misiuni franceze", in Analele Banatului. Arheologie—Istorie, Vol. XVIII, 2010, pp. 241–250.

- Eusebiu Narai, "Aspecte privind situația minorității germane din județele Caraș și Severin în anii 1944–1948", in Analele Banatului. Arheologie—Istorie, Vol. XVI, 2008, pp. 309–331.

- Mihai Adrian Panu, "Reprezentarea politică a minorității germane în Banatul interbelic", in Vasile Ciobanu, Sorin Radu (eds.), Partide politice și minorități naționale din România în secolul XX, Vol. V, pp. 118–127. Sibiu: TechnoMedia, 2010. ISBN 978-606-8030-84-5

- Alexandru Pițigoi, "Problema Banatului la Conferința de pace de la Paris în documente britanice", in Magazin Istoric, July 2019, pp. 10–14.

- Yovan Radonitch, The Banat and Serbo–Roumanian Frontier Problem. Paris: Ligue des Universitaires Serbo-Croato-Slovènes, 1919. OCLC 642630168

- I. D. Suciu, "Banatul și Unirea din 1918", in Studii. Revistă de Istorie, Issue 6/1968, pp. 1089–1104.

- Tudor-Radu Tiron, "O contribuție heraldică la istoria înaintașilor omului politic Andrei Mocioni de Foen (1812–1880), membru fondator al Academiei Române", in Revista Bibliotecii Academiei Române, Vol. 1, Issue 1, January–June 2016, pp. 27–51.

- Dumitru Tomoni, "Contribuții bănățene la Marea Unire", in Analele Banatului. Arheologie—Istorie, Vol. XVI, 2008, pp. 289–299.

- Smaranda Vultur, Francezi în Banat, bănățeni în Franța. Timișoara: Editura Marineasa, 2012. ISBN 978-973-631-698-2

- States and territories established in 1918

- States and territories disestablished in 1919

- 20th century in Vojvodina

- Aftermath of World War I in Hungary

- Former countries in the Balkans

- Former unrecognized countries

- History of Banat

- Social Democratic Party of Hungary

- States succeeding Austria-Hungary

- Yugoslav unification