History of the internal combustion engine

This article needs to be updated. (August 2017) |

Various scientists and engineers contributed to the development of internal combustion engines. In 1791, John Barber developed a turbine. In 1794 Thomas Mead patented a gas engine. Also in 1794 Robert Street patented an internal-combustion engine, which was also the first to use the liquid fuel (petroleum) and built an engine around that time. In 1798, John Stevens designed the first American internal combustion engine. In 1807, French engineers Nicéphore (who went on to invent photography) and Claude Niépce ran a prototype internal combustion engine, using controlled dust explosions, the Pyréolophore. This engine powered a boat on the Saône river, France. The same year, the Swiss engineer François Isaac de Rivaz built and patented a hydrogen and oxygen powered internal-combustion engine. The fuel was stored in a balloon and the spark was electrically ignited by a hand-operated trigger. Fitted to a crude four-wheeled wagon, François Isaac de Rivaz first drove it 100 meters in 1813, thus making history as the first car-like vehicle known to have been powered by an internal-combustion engine. In 1823, Samuel Brown patented the first internal combustion engine to be applied industrially in the U.S., one of his engines pumped water on the Croydon Canal from 1830 to 1836. He also demonstrated a boat using his engine on the Thames in 1827, and an engine-driven carriage in 1828. Father Eugenio Barsanti, an Italian engineer, together with Felice Matteucci of Florence invented the first real internal combustion engine in 1853. Their patent request was granted in London on June 12, 1854, and published in London's Morning Journal under the title "Specification of Eugene Barsanti and Felix Matteucci, Obtaining Motive Power by the Explosion of Gasses". In 1860, Belgian Jean Joseph Etienne Lenoir produced a gas-fired internal combustion engine. In 1864, Nicolaus Otto patented the first atmospheric gas engine. In 1872, American George Brayton invented the first commercial liquid-fueled internal combustion engine. In 1876, Nicolaus Otto, working with Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach, patented the compressed charge, four-stroke cycle engine. In 1879, Karl Benz patented a reliable two-stroke gas engine. In 1892, Rudolf Diesel developed the first compressed charge, a compression ignition engine. In 1926, Robert Goddard launched the first liquid-fueled rocket. In 1939, the Heinkel He 178 became the world's first jet aircraft. In 1954 German engineer Felix Wankel patented a "pistonless" engine using an eccentric rotary design.

Prior to 1860

- Before 350 BCE: Southeast Asians invent the fire piston, the first device to exploit compression-ignition and which ultimately inspired Rudolf Diesel in the invention of his eponymous engine.[1][2]

- 202 BCE–220 CE: The earliest hand-operated cranks appeared in China during the Han Dynasty.[3]

- 3rd century CE: Evidence of a crank and connecting rod mechanism dates to the Hierapolis sawmill in Byzantine Asia Minor , then part of the Roman Empire.

- 6th century: Several sawmills use a crank and connecting rod mechanism in Asia Minor and Syria, then part of the Byzantine Empire.

- 9th century: The crank appears in the mid-9th century in several of the hydraulic devices described by the Banū Mūsā brothers in their Book of Ingenious Devices.[4]

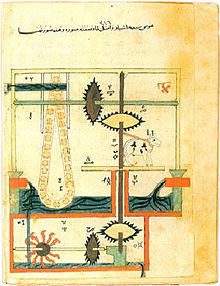

- 1206: Al-Jazari invented an early crankshaft,[5][6] which he incorporated with a crank-connecting rod mechanism in his twin-cylinder pump. Like the modern crankshaft, Al-Jazari's mechanism consisted of a wheel setting several crank pins into motion, with the wheel's motion being circular and the pins moving back-and-forth in a straight line.[5] The crankshaft described by al-Jazari[5][6] transforms continuous rotary motion into a linear reciprocating motion.

- 17th century: Samuel Morland experiments with using gunpowder to drive water pumps.

- 17th century: Christiaan Huygens designs gunpowder to drive water pumps, to supply 3000 cubic meters of water/day for the Versailles palace gardens, essentially creating the first idea of a rudimentary internal combustion piston engine.

- 1780s: Alessandro Volta built a toy electric pistol[7] in which an electric spark exploded a mixture of air and hydrogen, firing a cork from the end of the gun.

- 1791: John Barber receives British patent #1833 for A Method for Rising Inflammable Air for the Purposes of Producing Motion and Facilitating Metallurgical Operations. In it he describes a turbine.

- 1794: Robert Street built a compressionless engine. He was also the first to use liquid fuel in an internal combustion engine.[8]

- 1794: Thomas Mead patents a gas engine.[9]

- 1798: John Stevens builds the first double-acting, crankshaft-using internal combustion engine.

- 1801: Philippe LeBon D'Humberstein comes up with the use of compression in a two-stroke engine.

- 1807: Nicéphore Niépce installed his "moss, coal-dust and resin" fueled Pyréolophore internal combustion engine in a boat and powered up the river Saône in France. A patent was subsequently granted by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte on 20 July 1807.

- 1807: Swiss engineer François Isaac de Rivaz built an internal combustion engine powered by a hydrogen and oxygen mixture, and ignited by electric spark. (See 1780s: Alessandro Volta above.)[10]

- 1823: Samuel Brown patented the first internal combustion engine to be applied industrially, the gas vacuum engine. The design used atmospheric pressure, and was demonstrated in a carriage and a boat, and in 1830 commercially to pump water to the upper level of the Croydon Canal.

- 1824: French physicist Sadi Carnot established the thermodynamic theory of idealized heat engines.

- 1826 April 1: American Samuel Morey received a patent for a compressionless "Gas or Vapor Engine."[11] This is also the first recorded example of a carburetor.

- 1833: Lemuel Wellman Wright, UK patent no. 6525, table-type gas engine. Double-acting gas engine, first record of water-jacketed cylinder.[12]

- 1838: A patent was granted to William Barnett, UK patent no. 7615 April 1838. According to Dugald Clerk, this was the first recorded use of in-cylinder compression.[13]

- 1853–1857: Eugenio Barsanti and Felice Matteucci invented and patented the Barsanti-Matteucci engine, an internal combustion engine using the free-piston principle in an atmospheric two cycle engine.[14][15]

- 1856: in Florence at Fonderia del Pignone (now Nuovo Pignone, later a subsidiary of General Electric), Pietro Benini realized a working prototype of the Italian engine supplying 5 HP. In subsequent years he developed more powerful engines—with one or two pistons—which served as steady power sources, replacing steam engines.

- 1857: Eugenio Barsanti and Felice Matteucci describe the principles of the free piston engine where the vacuum after the explosion allows atmospheric pressure to deliver the power stroke (British patent no. 1625).[15]

1860–1920

- 1860: Jean Joseph Etienne Lenoir invented a gas-fired internal combustion engine, and applied for a patent titled Moteur à air dilaté par combustion des gaz. His engine is similar in appearance to a horizontal double-acting steam engine, with cylinders, pistons, connecting rods, and flywheel in which the gas essentially took the place of the steam. Allegedly, several of these engines were built and used commercially in Paris.[16] Friedrich Sass considers the Lenoir engine to be the first functional internal combustion engine.[17]

- 1861: Nicolaus Otto ordered Michael Joseph Zons to build a copy of the Lenoir engine for experimental purposes.[18] Later that year, Zons built a second engine for Otto, a four-cylinder, two-stroke unit.[19]

- 1861: Alphonse Beau de Rochas invented the four-stroke operating principle. He published an essay titled Nouvelles recherches sur les conditions pratiques de l'utilisation de la chaleur et en général de la force motrice. Avec application au chemin de fer et à la navigation, and applied for a patent. The patent was granted in France, however, it consists of text only, but does not include any drawings of a four-stroke engine. The patent was eventually declared invalid after two years; no copy has been kept in the French patent office's archive.[20]

- 1863: Otto designed an atmospheric gas engine, that was once again built by Zons.[21] Otto tried filing a patent application, but the patent was not granted in Prussia.[22]

- 1864: In Vienna, Siegfried Marcus put an atmospheric petrol engine on a handcart. Allegedly, it drove 200 metres.[23]

- 1864: Eugen Langen joined Otto, and improved the atmospheric gas engine.[24]

- 1865: Pierre Hugon started production of the Hugon engine, similar to the Lenoir engine, but with better economy, and more reliable flame ignition.[25]

- 1867: Otto and Langen exhibited their free piston engine at the Paris Exhibition in 1867, and they won the greatest award. It had less than half the gas consumption of the Lenoir or Hugon engines.[26]

- 1868: Eugen Langen and Nicolaus Otto obtained a patent on the atmospheric gas engine.[27]

- 1872: In America, George Brayton applied for a patent on Brayton's Ready Motor. It used constant pressure combustion, and was the first commercial liquid fuelled internal combustion engine. In 1876, it was put into production.[28]

- 1875: Nicolaus Otto, working with Franz Rings, designed the first functional compressed charge, four-stroke engine. In early 1876, it was tested. The engine was a single-cylinder unit, which displaced 6.1 dm3, and which was rated 3 PS (2,206 W) at 180/min, with a fuel consumption of 0.95 m3/PSh (1.29 m3/kWh).[29] In 1876, Wilhelm Maybach improved the engine by changing the connecting rod and piston design from trunk to crosshead, (now giving the engine a 400 mm stroke, increasing the displacement to 8.143 dm3), so it could be put into series production.[30]

- 1876: Otto applied for a patent on a stratified charge engine, that would use the four-stroke principle. The patent was granted in 1876 in Elsass-Lothringen, and transformed into a German Realm Patent in 1877 (DRP 532, 4 August 1877).[31]

- 1878: Dugald Clerk designed the first two-stroke engine with in-cylinder compression. He patented it in England in 1881.

- 1879: Karl Benz, working independently, was granted a patent for his reliable two-stroke, internal combustion engine, gas engine.

- 1882: James Atkinson invented the Atkinson cycle engine. Atkinson's engine had one power phase per revolution together with different intake and expansion volumes, potentially making it more efficient than the Otto cycle, but certainly avoiding Otto's patent.

- 1884: British engineer Edward Butler constructed the first petrol (gasoline) internal combustion engine. Butler invented the spark plug, ignition magneto, coil ignition and spray jet carburetor, and was the first to use the word petrol.[32]

- 1885: German engineer Gottlieb Daimler received a German patent for a supercharger [33]

- 1885/1886 Karl Benz designed and built his own four-stroke engine that was used in his automobile, which was developed in 1885, patented in 1886, and became the first automobile in series production.

- 1887: Gustaf de Laval introduces the de Laval nozzle

- 1889: Félix Millet begins development of the first vehicle to be powered by a rotary engine in transportation history.

- 1891: Herbert Akroyd Stuart built his oil engine, leasing rights to Hornsby of England to build them.

- 1892: Rudolf Diesel developed the first compressed charge, compression ignition engine .[34]

- 1893 February 23: Rudolf Diesel received a patent for his compression ignition (diesel) engine.

- 1896: Karl Benz invented the boxer engine, also known as the horizontally opposed engine, or the flat engine, in which the corresponding pistons reach top dead center at the same time, thus balancing each other in momentum.

- 1897: Robert Bosch was the first to adapt a magneto ignition to a vehicle engine.

- 1898: Fay Oliver Farwell designs the prototype of the line of Adams-Farwell automobiles, all to be powered with three or five cylinder rotary internal combustion engines.

- 1900: Rudolf Diesel demonstrated the diesel engine in the 1900 Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) using peanut oil fuel (see biodiesel).[35]

- 1900: Wilhelm Maybach designed an engine built at Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft—following the specifications of Emil Jellinek—who required the engine to be named Daimler-Mercedes after his daughter. In 1902 automobiles with that engine were put into production by DMG.[36][37]

- 1902: French engineer Léon Levavasseur invents the V8 engine internal combustion engine configuration, initially using it for aviation and speedboat propulsion.

- 1903: Konstantin Tsiolkovsky begins a series of theoretical papers discussing the use of rocketry to reach outer space. A major point in his work is liquid fueled rockets.

- 1903: Ægidius Elling builds a gas turbine using a centrifugal compressor which runs under its own power. By most definitions, this is the first working gas turbine.

- 1905: Alfred Buchi patents the turbocharger and starts producing the first examples.

- 1903–1906: The team of Armengaud and Lemale in France build a complete gas turbine engine. It uses three separate compressors driven by a single turbine. Limits on the turbine temperatures allow for only a 3:1 compression ratio, and the turbine is not based on a Parsons-like "fan", but a Pelton wheel-like arrangement. The engine is so inefficient, at about 3% thermal efficiency, that the work is abandoned.

- 1908: New Zealand inventor Ernest Godward started a motorcycle business in Invercargill and fitted the imported bikes with his own invention–a petrol economiser. His economisers worked as well in cars as they did in motorcycles.

- 1908: Hans Holzwarth starts work on extensive research on an "explosive cycle" gas turbine,[38] based on the Otto cycle. This design burns fuel at a constant volume and is somewhat more efficient. By 1927, when the work ended, he has reached about 13% thermal efficiency.

- 1908: The Seguin brothers (Augustin, Laurent and Louis) design the first rotary engine purposely designed for aircraft propulsion - the French Gnome Omega seven-cylinder, which is prototyped in 1908 and goes into production.[39]

- 1908: René Lorin patents a design for the ramjet engine.

- 1916: Auguste Rateau suggests using exhaust-powered compressors to improve high-altitude performance, the first example of the turbocharger.

1920–1980

- 1920: William Joseph Stern reports to the Royal Air Force that there is no future for the turbine engine in aircraft. He bases his argument on the extremely low efficiency of existing compressor designs. Due to Stern's eminence, his paper is so convincing there is little official interest in gas turbine engines anywhere, although this does not last long.

- 1921: Maxime Guillaume patents the axial-flow gas turbine engine. It uses multiple stages in both the compressor and turbine, combined with a single very large combustion chamber.

- 1923: Edgar Buckingham at the United States National Bureau of Standards publishes a report on jets, coming to the same conclusion as W.J. Stern, that the turbine engine is not efficient enough. In particular he notes that a jet would use five times as much fuel as a piston engine.[40]

- 1925: The Hesselman engine is introduced by Swedish engineer Jonas Hesselman represented the first use of direct gasoline injection on a spark-ignition engine.[41][42]

- 1925: Wilhelm Pape patents a constant-volume engine design.

- 1926: Alan Arnold Griffith publishes his groundbreaking paper Aerodynamic Theory of Turbine Design, changing the low confidence in jet engines. In it he demonstrates that existing compressors are "flying stalled", and that major improvements can be made by redesigning the blades from a flat profile into an airfoil, going on to mathematically demonstrate that a practical engine is definitely possible and showing how to build a turboprop.

- 1926: Robert Goddard launches the first liquid-fueled rocket

- 1927: Aurel Stodola publishes his "Steam and Gas Turbines"—basic reference for jet propulsion engineers in the US.

- 1927: A testbed single-shaft turbo-compressor based on Griffith's blade design is tested at the Royal Aircraft Establishment.

- 1929: Frank Whittle's thesis on jet engines is published.

- 1930: Schmidt patents a pulse-jet engine in Germany.

- 1935: Hans von Ohain creates plans for a turbojet engine and convinces Ernst Heinkel to develop a working model. Along with a single mechanic von Ohain develops the world's first turbojet on a test stand.

- 1936: French engineer René Leduc, having independently rediscovered René Lorin's design, successfully demonstrates the world's first operating ramjet.

- 1937: The first successful run of Sir Frank Whittle's gas turbine for jet propulsion.

- March, 1937: The Heinkel HeS 1 experimental hydrogen fueled centrifugal jet engine is tested at Hirth.

- 27 August 1939: Flight of the world's first turbojet power aircraft. Hans von Ohain's Heinkel He 178 V1 pioneer turbojet aircraft prototype makes its first flight, powered by an He S 3 von Ohain engine.

- 15 May 1941: The Gloster E.28/39 becomes the first British jet-engined aircraft to fly, using a Power Jets W.1 turbojet designed by Frank Whittle and others.

- 1942: Max Bentele discovers in Germany that turbine blades can break if vibrations are in its resonance range, a phenomenon already known in the US from the steam turbine experience.

- 18 July 1942: The Messerschmitt Me 262 first jet engine flight

- 1946: Samuel Baylin develops the Baylin Engine a three cycle internal combustion engine with rotary pistons. A crude but complex example of the future Wankel engine.[43]

- 1951: Engineers for The Texas Company—i.e. now Chevron—developed a four stroke engine with a fuel injector that employed what was called the Texaco Combustion Process, which unlike normal four stroke gasoline engines which used a separate valve for the intake of the air-gasoline mixture, with the T.C.P. engine the intake valve with a built in special shroud delivers the air to the cylinder in a tornado type fashion and then the fuel is injected and ignited by a spark plug. The inventors claimed their engine could burn on almost any petroleum based fuel of any octane and even some alcohol based fuels—e.g. kerosene, benzine, motor oil, tractor oil, etc.—without the pre-combustion knock and the complete burning of the fuel injected into the cylinder. While development was well advanced by 1950, there are no records of the T.C.P. engine being used commercially.[44]

- 1950s: Development begins by US firms of the Free-piston engine concept which is a crankless internal combustion engine.[45]

- 1954: Felix Wankel's first working prototype DKM 54 of the Wankel engine

1980 to present

- 1986: Benz Gmbh[46] files for patent protection for a form of Scotch yoke engine and begins development of same. Development subsequently abandoned.

- 1996: Ford Motor Company files patent for compact turbine engine.[47]

- 2004: Hyper-X first scramjet to maintain altitude

- 2004: Toyota Motor Corp files for patent protection for new form of Scotch yoke engine.[48]

Engine starting

Early internal combustion engines were started by hand cranking. Various types of starter motor were later developed. These included:

- An auxiliary petrol engine for starting a larger petrol or diesel engine. The Hucks starter is an example

- Cartridge starters, such as the Coffman engine starter, which used a device like a blank shotgun cartridge. These were popular for aircraft engines

- Pneumatic starters

- Hydraulic starters

- Electric starters

Electric starters are now almost universal for small and medium-sized engines, while pneumatic starters are used for large engines.

Modern vs. historical piston engines

The first piston engines did not have compression, but ran on an air-fuel mixture sucked or blown in during the first part of the intake stroke. The most significant distinction between modern internal combustion engines and the early designs is the use of compression of the fuel charge prior to combustion.

The problem of ignition of fuel was handled in early engines with an open flame and a sliding gate. To obtain a faster engine speed Daimler adopted a Hot Tube ignition which allowed 600 rpm immediately in his 1883 horizontal cylinder engine and very soon after over 900 rpm. Most of the engines of that time could not exceed 200 rpm due to their ignition and induction systems.[49]

The first practical engine, Lenoir's, ran on illuminating gas (coal gas). It wasn't until 1883, that Daimler created an engine that ran on liquid petroleum, a fuel called Ligroin which has a chemical makeup of Hexane-N. The fuel is also known as petroleum naphtha.

Otto's first engines were push engines which produced a push through the entire stroke (like a Diesel). Daimler's engines produced a rapid pulse, more suitable for mobile engine use.

See also

- Bertha Benz Memorial Route, commemorating the world's first long-distance journey with an automobile propelled by an internal combustion engine in 1888.

- Harry Ricardo

- Timeline of heat engine technology

- Timeline of motor vehicle brands

References

- ^ Ogata, Masanori; Shimotsuma, Yorikazu (October 20–21, 2002), "Origin of Diesel Engine is in Fire Piston of Mountainous People Lived in Southeast Asia", First International Conference on Business and technology Transfer, Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers, archived from the original on 2007-05-23, retrieved 2020-12-01

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1965), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering, Cambridge University Press, pp. 140–141, ISBN 9780521058032

- ^ Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Pages 118–119.

- ^ A. F. L. Beeston, M. J. L. Young, J. D. Latham, Robert Bertram Serjeant (1990), The Cambridge History of Arabic Literature, Cambridge University Press, p. 266, ISBN 978-0-521-32763-3

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Sally Ganchy, Sarah Gancher (2009), Islam and Science, Medicine, and Technology, The Rosen Publishing Group, p. 41, ISBN 978-1-4358-5066-8

- ^ a b Paul Vallely, How Islamic Inventors Changed the World, The Independent, 11 March 2006.

- ^ "ELECTRIC PISTOL". ppp.unipv.it.

- ^ "The Early History of Combustion Engines".

- ^ Spies, Albert (1892–95). Modern gas and oil engines. New York, The Cassier's magazine company – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The History of the Automobile - Gas Engines". About.com. 2009-09-11. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- ^ Hardenberg, Horst O. (1992). Samuel Morey and his atmospheric engine. SP-922. Warrendale, Pa.: Society of Automotive Engineers. ISBN 978-1-56091-240-8.

- ^ Dugald Clerk, "Gas and Oil Engines", Longman Green & Co, (7th Edition) 1897, pp 3-5.

- ^ Dugald Clerk, "Gas and Oil Engines", Longman Green & Co, 1897.

- ^ "The Historical Documents". Barsanti e Matteucci. Fondazione Barsanti & Matteucci. 2009. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

- ^ a b Ricci, G.; et al. (2012). "The First Internal Combustion Engine". In Starr, Fred; et al. (eds.). The Piston Engine Revolution. London: Newcomen Society. pp. 23–44. ISBN 978-0-904685-15-2.

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 11

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 15

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 20

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 23

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 56–58

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 27

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 28

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 79

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 29–31

- ^ Rudolf Krebs: Fünf Jahrtausende Radfahrzeuge: 2 Jahrhunderte Straßenverkehr mit Wärmeenergie. Über 100 Jahre Automobile. Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1994, ISBN 9783642935534, p. 203

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 34–35

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 31

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 413–414

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 43–44

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 45

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6, p. 51–52

- ^ "Hiram Maxim and Edward Butler:Two local inventors". Bexley. Bexley. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ^ "Gottlieb Daimler".

- ^ DE patent 67207 Rudolf Diesel: "Arbeitsverfahren und Ausführungsart für Verbrennungskraftmaschinen" pg 4.

- ^ Martin Leduc, "Biography of Rudolph Diesel" Archived 2010-06-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Wilhelm Maybach". www.nndb.com.

- ^ The history behind the Mercedes-Benz brand and the three-pointed star Archived 2010-10-25 at the Wayback Machine. eMercedesBenz.com. April 17, 2008.

- ^ Museum, Deutsches. "Deutsches Museum: Holzwarth Gas Turbine, 1908". www.deutsches-museum.de.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution (2018). "Gnome Omega No. 1 Rotary Engine". National Air and Space Museum. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on August 17, 2018. Retrieved Aug 17, 2018.

- ^ "Report #159" (PDF). casi.ntrs.nasa.gov.

- ^ Lindh, Björn-Eric (1992). Scania fordonshistoria 1891-1991 (in Swedish). ISBN 978-91-7886-074-6. (Translated title: Vehicle history of Scania 1891-1991)

- ^ Volvo – Lastbilarna igår och idag (in Swedish). 1987. ISBN 978-91-86442-76-7. (Translated title: Volvo trucks yesterday and today)

- ^ "How the Baylin Engine Works." Popular Mechanics, July 1946, pp. 131-132.

- ^ "Engine With A Built In Tornado." Popular Mechanic, September 1950, pp. 94-95.

- ^ "Revolution of the Free-Piston Engine" Popular Mechanics, September 1950, pp. 114-118.

- ^ "BENZ GmbH Werkzeugsysteme". www.benz-tools.de.

- ^ "US Patent # 5,584,174. Power turbine flywheel assembly for a dual shaft turbine engine - Patents.com". patents.com.

- ^ Patent application number: JP2004293387.

- ^ "1883: High-speed engine with hot-tube ignition".

Further reading

- Sloss, Robert (January 1911). "The Children Of The Gas-Engine: The Revolution In Speed And In Convenience In Transportation - Automobiles, Motor-Cycles, Motor-Boats, Aeroplanes And Other Queer Craft That Ten Years Have Brought". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXI: 13869–13877. Retrieved 2009-07-10.