Water scarcity in Africa

Water production and consumption growth rates is key for African countries to achieve efficient and equitable allocation of these resources.

The 2017 Report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations indicates that Growing water scarcity is now one of the leading challenges for sustainable development. This is because an increasing number of the river basins have reached conditions of water scarcity through the combined demands of agriculture and other sectors.

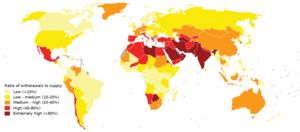

Levels of water scarcity in Africa are predicted to reach dangerously high levels by 2025. It is estimated that about two-third of the world's population may suffer from fresh water shortage by 2025. Although, the earth is made up of 70 percent water, only 3 percent of this water is actually fresh water, which is suitable for consumption.[1] Water scarcity is the lack of fresh water resources to meet the standard water demand. Water scarcity can be caused by droughts, lack of rainfall, or human and animal pollutions. Its main causes in Africa are physical and economic scarcity, rapid population growth, and climate change.

Although Sub-Saharan Africa has a plentiful supply of rainwater, it is seasonal and unevenly distributed, leading to frequent floods and droughts.[2] Additionally, prevalent economic development and poverty issues, compounded with rapid population growth and rural-urban migration have rendered Sub-Saharan Africa as the world's poorest and least developed region.[2]

Impacts of water scarcity in Africa range from health (women and children are particularly affected) to education, agricultural productivity, sustainable development as well as the potential for more water conflicts.

To adequately address the issue of water scarcity in Africa, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa emphasizes the need to invest in the development of Africa's potential water resources to reduce unnecessary suffering, ensure food security, and protect economic gains by effectively managing droughts, floods, and desertification.[3] Some suggested and ongoing efforts to achieve this include an emphasis on infrastructural implementations and improvements of wells, rainwater catchment systems, and clean-water storage tanks.

Background

When there is a geographic and temporal imbalance between the demand of freshwater and its availability, that is known as water scarcity. In this regard, scarcity can be defined as either the scarcity in availability due to physical shortage or scarcity in access due to lack of adequate infrastructure.[8] Water scarcity is the consequence of both natural and man-made causes. Water scarcity or lack of safe drinking water (physical water scarcity) is one of the world's leading problems affecting more than 1.1 billion people globally, meaning that one in every six people lacks access to safe drinking water.[9]

The Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation set up by the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) defines safe drinking water as "water with microbial, chemical and physical characteristics that meets WHO guidelines or national standards on drinking water quality." Hydrologists generally assess water scarcity by looking at a population-to-water equation that treats 1,700 cubic meters per person as the national threshold for meeting water requirements for agricultural and industrial production, energy, and the environment.[10] Availability below the threshold of 1,000 cubic meters represents a state of "water scarcity", while anything below 500 cubic meters represents a state of "absolute scarcity".[10]

In 2019, the World Health Organization and the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund recoded that approximately 2.2 billion people do no have access to sanitized water sources.[11] As of 2006, one third of all nations suffered from clean water scarcity,[3] but Sub-Saharan Africa had the largest number of water-stressed countries of any other place on the planet and of an estimated 800 million people who live in Africa, 300 million live in a water stressed environment.[12] According to findings presented at the 2012 Conference on "Water Scarcity in Africa: Issues and Challenges", it is estimated that by 2030, 75 million to 250 million people in Africa will be living in areas of high water stress, which will likely displace anywhere between 24 million and 700 million people as conditions become increasingly unlivable.[12]

Regional variance

Northern Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa are progressing towards the Millennium Development Goal on water at different paces. While Northern Africa has 92% safe water coverage, Sub-Saharan Africa remains at a low 60% of coverage – leaving 40% of the 783 million people in that region without access to clean drinking water.[2]

Some of these differences in clean water availability can be attributed to Africa's extreme climates. Although Sub-Saharan Africa has a plentiful supply of rainwater, it is seasonal and unevenly distributed, leading to frequent floods and droughts.[2] Additionally, prevalent economic development and poverty issues, compounded with rapid population growth and rural-urban migration have rendered Sub-Saharan Africa as the world's poorest and least developed region.[2] Thus, this poverty constrains many cities in this region from providing clean water and sanitation services and preventing the further deterioration of water quality even when opportunities exist to address these water issues.[2] Additionally, the rapid population growth leads to an increased number of African settlements on flood-prone, high-risk land.[2]

The latest report of the SDG goal 6 has mentioned various facts about water status in sub-Saharan Africa including the lack of hygiene and its impact on the nutritional status especially among children due to increased rate of infectious diseases. Also, almost 1/3 of the sub-Saharan population are in danger of hunger due to lack of access to food. Furthermore, sub-Saharan Africa lacks access to safe drinking water by 76% percent while only 6% of Europe and Northern America is not covered.[13]

Causes

Physical and economic scarcity

Water scarcity is both a natural and human-made phenomenon.[14] It is thus essential to break it down into two general types: Economic scarcity and physical scarcity. Economic scarcity refers to the fact that finding a reliable source of safe water is time-consuming and expensive. Alternatively, physical scarcity is when there simply is not enough water within a given region.[15]

The 2006 United Nations Economic Commission for Africa estimates that 300 million out of the 800 million who live on the African continent live in a water-scarce environment.[3] Specifically in the very north of Africa, as well the very south of Africa, the rising global temperatures accompanying climate change have intensified the hydrological cycle that leads to drier dry seasons, thus increasing the risk of more extreme and frequent droughts. This significantly impacts the availability, quality and quantity of water due to reduced river flows and reservoir storage, lowering of water tables and drying up of aquifers in the northern and southern regions of Africa.

Included in the category of physical scarcity is the issue of overexploitation. This is contributing to the shrinking of many of Africa's great lakes, including the Nakivale, Nakuru, and Lake Chad, which has shrunk to 10% of its former volume.[10] In terms of policy, the incentives for overuse are among the most damaging, especially concerning ground water extraction. For ground water, once the pump is installed, the policy of many countries is to only constrain removal based on the cost of electricity, and in many cases subsidize electricity costs for agricultural uses, which damages incentives to conserve such resources.[10] Additionally, many countries within Africa set the cost of water well below cost-recovery levels, thus discouraging efficient usage and threatening sustainability.[10]

The majority of Sub-Saharan Africa suffers from economic scarcity because of the population's lack of the necessary monetary means to utilize adequate sources of water. Both political reasons and ethnic conflict have contributed to this unequal distribution of resources. Out of the two forms of water scarcity, economic scarcity can be addressed quickly and effectively with simple infrastructure to collect rainwater from roofs and dams, but this requires economic resources that many of these areas lack due to an absence of industrial development and widespread poverty.[15]

Population growth

Over the past century, the global population has more than doubled.[16] Africa's population is notably the fastest growing in the world. It is expected to increase by roughly 50% over the next 18 years, growing from 1.2 billion people today to over 1.8 billion in 2035. In fact, Africa will account for nearly half of global population growth over the next two decades.[17] There is also a simple but appreciable equation that, as population increases, so does water demand. At the same time, the water resources in African region are gradually diminishing due to the habitation in places that were previously water sources. As the population increases rapidly, there is urgent demands for improved health, quality of life, food security, and ‘lubrication’ of industrial growth, which also place severe constraints o the water available to achieve these goals.[18]

The growing population will only exacerbate the water scarcity crisis as more pressure is placed on the availability and access of water resources. “Today, 41% of the world's population lives in river basins that are under water stress”.[19] This raises a major concern as many regions are reaching the limit at which water services can be sustainably delivered.[8] Globally, about 55 percent of the world's population live in urban areas, and by 2030, there might be a 5 percent increase in this ratio. This is the same experience in Africa. Big cities like Lagos, Kinshasa and Nairobi have doubled their population within a fifteen years period.[20] Although people are migrating into these urban cities, the availability of fresh water has stayed the same, or in some cases reduced, since water is a finite substance.The rising population in African cities creates a link to the imbalance between the supply of water and the demands in those cities.[20]

Aside urbanization contributing to the imbalance between the demand and supply of water, urbanization also causes an increase in water pollution. As a result of more people moving into cities, there is increased deposit of sewage and waste into water bodies.[21] In developing countries, over 90 percent of the sewage generated are disposed into water bodies and left untreated. Also, sewage system are inefficiently run, such that leaks from sewage pipes are left unattended to, which eventually leak into the soil and causes further pollution of underground water.[21]

Climate change

Climate change includes both the global warming driven by human emissions of greenhouse gases, and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns.[22] As Climate change warms the planet, the world’s hottest geographies become more scorching. Simultaneously, clouds move farther away from the equator towards the pole by a climate-change phenomenon called Hadley Cell Expansion. This deprives equatorial regions like sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and Central America of life-giving rainwater.[23] If global temperatures continue to rise, rainfall will increasingly become a beast of extremes: long dry spells here, dangerous floods there – and in some places, intense water shortages.

Climate change is disrupting weather patterns, leading to extreme weather events, unpredictable water availability, exacerbating water scarcity and contaminating water supplies. According to the Africa Partnership Forum, "Although Africa is continent least responsible for climate change, it is particularly vulnerable to the effects," and the long-term impacts include, "changing rainfall patterns affecting agriculture and reducing food security; worsening water security; decreasing fish resources in large lakes due to rising temperature; shifting vector-borne diseases; rising sea level affecting low-lying coastal areas with large populations; and rising water stress".[24] Such impacts can drastically affect the quantity and quality of water that children need to survive.[25]

Studies predict that by the year 2050 the rainfall in Sub-Saharan Africa could drop by 10%, which will cause a major water shortage. This 10% decrease in precipitation would reduce drainage by 17% and the regions which are receiving 500–600 mm/year rainfall will experience a reduction by 50–30% respectively in the surface drainage.[26] Additionally, the Human Development Report predicts warming paired with 10% less rainfall in interior regions of Africa, which will be amplified by water loss due to water loss increase from rising temperature.[10] Droughts and floods are considered to be the most dangerous threat to physical water scarcity.[27] This warming will be greatest over the semi-arid regions of the Sahara, along the Sahel, and interior areas of southern Africa.[10] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports that climate change in Africa has manifested itself in more intense and longer droughts in the subtropics and tropics, while arid or semi-arid areas in northern, western, eastern, and parts of southern Africa are becoming drier and more susceptible to variability of precipitation and storms.[24] Climate change has contributed immensely to the already exacerbating water crisis situation in Africa and globally, making the World Health organization declare it as the greatest threat to global health in the 21st century.[28]

The Human Development Report goes on to explain that because of Africa's dependence on rain-fed agriculture, widespread poverty, and weak capacity, the water issues caused by climate change impact the continent much more violently compared to developed nations that have the resources and economic diversity to deal with such global changes. This heightened potential for drought and falling crop yields will most likely lead to increased poverty, lower incomes, less secure livelihoods, and an increased threat of chronic hunger for the poorest people in sub-Saharan Africa.[10] Overall this means that water stress caused by changing amounts of precipitation is particularly damaging to Africa and thus climate change is one of the major obstacles the continent must face when trying to secure reliable and clean sources of water. “66 percent of people dwelling in sub-Saharan Africa live in areas of little to no rainfall which often results in failed vegetation and agricultural efforts. Currently, more than 300 to 800 sub-Saharan Africans live in a water-scarce location, and it has been predicted to get worse if the trend of climate change continues.”[27]

Impacts

Health

The most immediately apparent impact of water scarcity in Africa is on the continent's health. With a complete lack of water, humans can only live up to 3 to 5 days on average.[29] This often forces those living in water deprived regions to turn to unsafe water resources, which, according to the World Health Organization, contributes to the spread of waterborne diseases including typhoid fever, cholera, dysentery and diarrhea, and to the spread of diseases such as malaria whose vectors rely on such water resources, and can lead to diseases such as trachoma, plague, and typhus.[30] Additionally, water scarcity causes many people to store water within the household, which increases the risk of household water contamination and incidents of malaria and dengue fever spread by mosquitoes.[30] These waterborne diseases are not usually found in developed countries because of sophisticated water treatment systems that filter and chlorinate water, but for those living with less developed or non-existent water infrastructure, natural, untreated water sources often contain tiny disease-carrying worms and bacteria.[15] Although many of these waterborne sicknesses are treatable and preventable, they are nonetheless one of the leading causes of disease and death in the world. Globally, 2.2 million people die each year from diarrhea-related disease, and at any given time fifty percent of all hospital beds in the world are occupied by patients suffering from water-related diseases.[9] Infants and children are especially susceptible to these diseases because of their young immune systems,[15] which lends to elevated infant mortality rates in many regions of Africa. Water scarcity has a big impact on hygiene.

When infected with these waterborne diseases, those living in African communities suffering from water scarcity cannot contribute to the community's productivity and development because of a simple lack of strength. Additionally, individual, community and governmental economic resources are sapped by the cost of medicine to treat waterborne diseases, which takes away from resources that might have potentially been allocated in support of food supply or school fees.[15] Also, in term of governmental funding, the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) estimates that in Sub-Saharan Africa, treatment of diarrhea due to water contamination consumes 12% of the country's health budget. With better water conditions, the burden on healthcare would be less substantial, while a healthier workforce[31] would stimulate economic growth and help alleviate the prevalence of poverty.

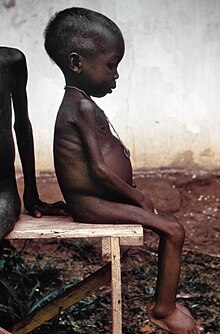

Along with waterborne diseases and unsafe drinking water, malnutrition is also a major cause of death in Africa. Some of the malnutrition is caused by reduced agricultural production in some regions of Africa due to water scarcity. According to a 2008 review an estimated 178 million children under age 5 are stunted, most of whom live in sub-Saharan Africa.[32] The cause of stunting is undernutrition in children.

Women

African women and men's divergent social positions lead to differences in water responsibilities, rights, and access,[33] and so African women are disproportionally burdened by the scarcity of clean drinking water. In most African societies, women are seen as the collectors, managers, and guardians of water, especially within the domestic sphere that includes household chores, cooking, washing, and child rearing.[34] Because of these traditional gender labor roles, women are forced to spend around sixty percent of each day collecting water, which translates to approximately 200 million collective work hours by women globally per day[35] and a decrease in the amount of time available for education. Water scarcity exacerbates this issue, as indicated by the correlation of decrease in access to water with a decrease in combined primary, secondary, and tertiary enrollment of women.[33]

For African women, their daily role in clean water retrieval often means carrying the typical jerrycan that can weigh over 40 pounds when full[15] for an average of six kilometers each day.[9] This has health consequences such as permanent skeletal damage from carrying heavy loads of water over long distances each day,[36] which translates to a physical strain that contributes to increased stress, increased time spent in health recovery, and decreased ability to not only physically attend educational facilities, but also mentally absorb education due to the effect of stress on decision-making and memory skills. Also, in terms of health, access to safe and clean drinking water leads to greater protection from water-borne illnesses and diseases which increases women's capabilities to attend school.[33]

The detriment water scarcity has on educational attainment for women, in turn, affects the social and economic capital of women in terms of leadership, earnings, and working opportunities.[36] As a result of this, many women are unable to hold employment. The lost number of potential school days and education hinders the next generation of African women from breaking out of the cycle of unequal opportunity for gainful employment, which serves to perpetuate the prevalence of unequal opportunity for African women and adverse effects associated with lacking income from gainful employment. Thus, improved access to water influences women's allocation of time, level of education, and as a result their potential for higher wages associated with recognized and gainful employment.[33]

Education

In addition, the issue of water scarcity in Africa prevents many young children from attending school and receiving an education. These children are expected to not only aid their mothers in water retrieval but to also help with the demands of household chores that are more time-intensive because of a lack of readily available water. Furthermore, a lack of clean water means the absence of sanitary facilities and latrines in schools. This affects more female children as they hit puberty. In terms of lost educational opportunity, it is estimated that this would result in 272 million more school attendance days per year if adequate investment were made in drinking water and sanitation.[35]

For parents, an increase in access to reliable water resources reduces vulnerability to shocks, which allows for increased livelihood security and for families to allocate a greater portion of their resources to care for their children. This means improved nutrition for children, a reduction in school days missed due to health issues, and greater flexibility to spend resources on providing for the direct costs associated with sending children to school. Also, if families escape forced migration due to water scarcity, children's educational potential is even further improved with better stability and uninterrupted school attendance.[37]

Agriculture

The Human Development Report reports that human use of water is mainly allocated to irrigation and agriculture. In developing areas, such as those within Europe, agriculture accounts for more than 80% of water consumption.[10] This is due to the fact that it takes about 3,500 liters of water to produce enough food for the daily minimum of 3,000 calories, and food production for a typical family of four takes a daily amount of water equivalent to the amount of water in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.[10] Because the majority of Africa remains dependent on an agricultural lifestyle and 80% to 90% of all families in rural Africa rely upon producing their own food,[36] water scarcity translates to a loss of food security. Water, agriculture, nutrition, and health have always been linked but recently became recognized and researched as a cause and effect loop. More than 70% of agriculture practiced in Sub-Saharan Africa is rainfed agriculture. With the increasing variability of current weather patterns the crops and harvests are more prone to being affected by droughts and floods. Food and nutrition security is defining the development agenda in Sub-Saharan Africa.[39]

According to the UN Economic Commission for Africa and New Partnership for Africa's Development, "irrigation is key to achieving increased agricultural production that is important for economic development and for attaining food security". Most of the rural African communities are currently not tapping into their irrigation potential.[36] Irrigation agriculture only accounts for 20% of agriculture types globally.[40] In Sub-Saharan Africa the governments have historically played a large part in irrigation development. Starting in the 1960s donors like the World Bank supported these African governments in the development of irrigations systems.[41] However, in the years since, irrigation agriculture has produced a lower than expected crop yield.[40] According to the World Bank the agriculture production in Sub-saharan Africa could nearly triple by 2050.[citation needed] The Sustainable Development Goal 2 aims to end hunger and promote sustainable agriculture to achieve food and nutrition security.[13] There needs to be a shift from high-yield crop production to a more diversified cropping system, including underutilized nutritious crops that will contribute to dietary diversity and achieve daily nutrient goals.[39]

But for many regions, there is a lack of financial and human resources to support infrastructure and technology required for proper crop irrigation. Because of this, the impact of droughts, floods, and desertification is greater in terms of both African economic loss and human life loss due to crop failure and starvation. In a study conducted by the World Bank, they found that, on average, individuals who suffer from malnutrition lose 10% of their potential lifetime earnings. They also found that countries lose 2%-3% of their GDP due to undernutrition.[42]

Additionally, lack of water causes many Africans to use wastewater for crop growth, causing a large number of people to consume foods that can contain chemicals or disease-causing organisms transferred by the wastewater.[30] Greywater constructed wetlands and modified sand filters are two methods of greywater filtration that have been proposed. These methods allow for greywater to be purified or filtered to remove biological hazards from the water that would not be safe to use in agriculture.[43] Thus, for the extremely high number of African areas suffering from water scarcity issues, investing in development means sustainably withdrawing from clean freshwater sources, ensuring food security by expanding irrigation areas, and effectively managing the effects of climate change.[3] The sustainable development goal report aims at increasing safe wastewater use to contribute to increasing food production and improved nutrition.[13]

Productivity and development

Poverty is directly related to the accessibility of clean drinking water- without it, the chances of breaking out of the poverty trap are extremely slim. This concept of a "water poverty trap" was developed by economists specifically observing sub-Saharan Africa and refers to a cycle of financial poverty, low agricultural production, and increasing environmental degradation.[33] In this negative feedback loop, this creates a link between the lack of water resources with the lack of financial resources that affect all societal levels including individual, household, and community.[33] Within this poverty trap, people are subjected to low incomes, high fixed costs of water supply facilities, and lack of credit for water investments, which results in a low level of investment in water and land resources, lack of investment in profit-generating activities, resource degradation, and chronic poverty.[33] Compounding on this, in the slums of developing countries, poor people typically pay five to ten times more per unit of water than do people with access to piped water because of issues – including the lack of infrastructure and government corruption – which is estimated to raise the prices of water services by 10% to 30%.[36][44]

So, the social and economic consequences of a lack of clean water penetrate into realms of education, opportunities for gainful employment, physical strength and health, agricultural and industrial development, and thus the overall productive potential of a community, nation, and/or region. Because of this, the UN estimates that Sub-Saharan Africa alone loses 40 billion potential work hours per year collecting water.[15]

Conflict

The population growth across the world and the climate change are two factors that together could give rise to water conflicts in many parts of the world.[45] Already, the explosion of populations in developing nations within Africa combined with climate change is causing extreme strain within and between nations. In the past, countries have worked to resolve water tensions through negotiation, but there is predicted to be an escalation in aggression over water accessibility.

Africa's susceptibility to potential water-induced conflict can be separated into four regions: the Nile, Niger, Zambezi, and Volta basins.[44] Running through Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan, the Nile's water has the potential to spark conflict and unrest.[44] In the region of the Niger, the river basin extends from Guinea through Mali and down to Nigeria. Especially for Mali – one of the world's poorest countries – the river is vital for food, water and transportation, and its over usage is contributing to an increasingly polluted and unusable water source.[44] In southern Africa, the Zambezi river basin is one of the world's most over-used river systems, and so Zambia and Zimbabwe compete fiercely over it. Additionally, in 2000, Zimbabwe caused the region to experience the worst flooding in recent history when the country opened the Kariba Dam gates.[44] Finally, within the Volta river basin, Ghana is dependent on its hydroelectric output but plagued by regular droughts which affect the production of electricity from the Akosombo Dam and limit Ghana's ability to sustain economic growth. Paired with the constraints this also puts on Ghana's ability to provide power for the area, this could potentially contribute to regional instability.[44]

At this point, federal intelligence agencies have issued the joint judgment that in the next ten years, water issues are not likely to cause internal and external tensions that lead to the intensification war. But if current rates of consumption paired with climatic stress continue, levels of water scarcity in Africa are predicted by UNECA to reach dangerously high levels by 2025. This means that by 2022 there is the potential for a shift in water scarcity's potential to contribute to armed conflict.[46] Based on the classified National Intelligence Estimate on water security, requested by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and completed in Fall 2011, after 2022 water will be more likely to be used as a weapon of war and potential tool for terrorism, especially in North Africa.[46] On World Water Day, the State Department stated that water stress, "will likely increase the risk of instability and state failure, exacerbate regional tensions and distract countries from working with the United States on important policy objectives." Specifically referring to the Nile in Egypt, Sudan, and nations further south, the report predicts that upstream nations will limit access to water for political reasons and that terrorists may target water-related infrastructures, such as reservoirs and dams, more frequently.[46] Because of this, the World Economic Forum's 2011 Global Risk Report has included water scarcity as one of the world's top five risks for the first time.

Approaches

Technologies

The more basic solutions to help provide Africa with drinkable and usable water include well-digging, rain catchment systems, de-worming pills, and hand pumps, but high demand for clean water solutions has also prompted the development of some key creative solutions as well.

Some non-profit organizations have focused on the aspect of drinking water contamination from sewage waste by installing cost-effective and relatively maintenance-free toilets, such as Drop In The Bucket's "Eco-sanitation Flush Toilet"[47] or Pump Aid's "Elephant Toilet".[48] The Elephant Toilet uses community-sourced resources in construction to build a relatively simple waste disposal mechanism that separates solids from liquids to promote faster decomposition and lower the impact on ground water.[48] In comparison, the Eco-Sanitation Flush Toilet also uses no power of any kind, but actually treats sewage rather than just storing it so that the toilet's output is only water.[47] Both solutions are then simple for residents of African communities to maintain and have a notable impact on the cleanliness of local water sources.

Other solutions to clean water scarcity issues have focused on innovative pump systems, including hand-pumps, Water for People's "Play Pumps",[49] and Pump Aid's "Elephant Pumps".[48] All three designs are built to aid communities in drawing clean water from wells. The hand pump is the most basic and simple to repair, with replacement parts easily found.[50] Using a more creative approach, Play Pumps combine child's play with clean water extraction through the use of playground equipment, called a roundabout. The idea behind this is as children play on the roundabout, water will simultaneously be pumped from a reservoir tank to either toilets, hand-washing stations, or for drinking water.[48] Some downsides to the PlayPump, though, are its inability to address situations of physical water scarcity and the danger of exploitation when children's play is equated with pumping water.[51] Alternatively, Elephant Pumps are simple hand water pumps. After a well is prepared, a rope-pump mechanism is installed that is easy to maintain, uses locally sourced parts, and can be up and running in the time span of about a week.[48] The Elephant Pump can provide 250 people with 40 litres of clean water per person per day.[52]

Moving beyond sanitary waste disposal and pumps, clean water technology can now be found in the form of drinking straw filtration. Used as solution by Water Is Life, the straw is small, portable, and costs US$10 per unit.[53] The filtration device is designed to eliminate waterborne diseases, and as a result, provide safe drinking water for one person for one year.[53]

Overall, a wide range of cost-effective, manageable, and innovative solutions are available to help aid Africa in producing clean, disease-free water. Ultimately what it comes down to is using technology appropriate for each individual community's needs. For the technology to be effective, it must conform to environmental, ethical, cultural, social, and economic aspects of each Africa community.[54] Additionally, state governments, donor agencies, and technological solutions must be mindful of the gender disparity in access to water so as to not exclude women from development or resource management projects.[33] If this can be done, with sufficient funding and aid to implement such technologies, it is feasible to eliminate clean water scarcity for the African continent by the Millennium Development Goal deadline of 2012.

Since that deadline has passed, the Sustainable Development Goals are what we are striving for by the year 2030. SDGs are intersectional and interdependent, it's important to find modern solutions to save water through decreasing water use in irrigation by using more treated wastewater and shifting to less water dependent crops in regions with water scarcity. Another solution that contribute to sanitation and water preservation is EcoSan technologies that aim to benefit from the human waste in agriculture and reduce water pollution. (NBSs) Natural-Based Solutions are suggested as a successful alternative towards achieving the six SDG, NBSs include means to improve access to water with high caliber.[13]

International and non-governmental organizations' efforts

To adequately address the issue of water scarcity in Africa, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa emphasizes the need to invest in the development of Africa's potential water resources to reduce unnecessary suffering, ensure food security, and protect economic gains by effectively managing droughts, floods, and desertification.[3] Some suggested and ongoing efforts to achieve this include an emphasis on infrastructural implementations and improvements of wells, rainwater catchment systems, and clean-water storage tanks.

Efforts made by the United Nations in compliance with the Millennium Development Goals have targeted water scarcity not just for Africa, but globally. The compiled list includes eight international development goals, seven of which are directly impacted by water scarcity. Access to water affects poverty, food scarcity, educational attainment, social and economic capital of women, livelihood security, disease, and human and environmental health.[55] Because addressing the issue of water is so integral to reaching the MDGs, one of the sub-goals includes halving the proportion of the globe's population without sustainable access to safe drinking water by 2015. In March 2012, the UN announced that this goal has been met almost four years in advance, suggesting that global efforts to reduce water scarcity are on a successful trend.[56]

As one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, the United States plays an integral role in promoting solutions to aid with clean water scarcity. One of many efforts include USAID's WASH- the WASH for Life partnership with the Gates Foundation- that works to promote water, sanitation, and hygiene. With this, the U.S. "will identify, test, and scale up evidence-based approaches for delivering these services to people in some of the poorest regions".[56] Additionally, in March 2012, Hillary Clinton announced the U.S. Water Partnership, which will bring together people from the private sector, the philanthropic community, non-governmental organizations, academics, experts, and the government in an attempt to look for system-wide solutions.[56] The technologies and ability to tackle the issue of water scarcity and cleanliness are present, but it is highly a matter of accessibility. Thus, the partnership will aim at making these solutions available and obtainable at a local level.

In addition to the role the United States, the United Nations, and other international governmental bodies, a number of charitable organizations work to provide clean water in Africa and elsewhere around the world. These charities are based on individual and group donations, which are then invested in a variety of methods and technologies to provide clean water.[57]

In 2015, safe drinking water and sanitation sources have been provided to 90% of the world's inhabitants because of the efforts that had been made to achieve the MDGs. In continuation of this progress the UN[13] have been recognized to include “Clean water and Sanitation” as the goal number six to “Ensure access to water and sanitation for all”. The goal depends on the availability of enough fresh water of the world to achieve universal access to drinking and clean water for sanitation, but the lack of planning and shortage of investment is what the world needs to focus on. The main targets of the six SDG is that by 2030, the world will ensure water access for all, provide sanitary resources especially for people at risk, increase waste treatment and decrease the rate of water pollution. In addition to establishing new collaborative efforts on the international and local levels to improve water management systems.[13]

Limitations

Africa is home to both the largest number of water-scarce countries out of any region, as well as home to the most difficult countries to reach in terms of water aid. The prevalence of rural villages traps many areas in what the UN Economic Commission for Africa refers to as the "Harvesting Stage",[3] which makes water-scarce regions difficult to aid because of a lack of industrial technology to make solutions sustainable. In addition to the geographic and developmental limiting factors, a number of political, economic reasons also stand in the way of ensuring adequate aid for Africa. Politically, tensions between local governments versus foreign non-governmental organizations impact the ability to successfully bring in money and aid-workers. Economically, urban areas suffer from extreme wealth gaps in which the overwhelming poor often pay four to ten times more for sanitary water than the elite, hindering the poor from gaining access to clean water technologies and efforts.[3] As a result of all these factors, it is estimated that fifty percent of all water projects fail, less than five percent of projects are visited, and less than one percent have any long term monitoring.[35]

See also

- Water in Africa

- 2007 African floods

- 2009 West Africa floods

- Millennium Development Goals

- Water issues in developing countries

- Water politics

- Water crisis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Atmospheric water generator

- Desalination

References

- ^ "Water Scarcity | Threats | WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g "International Decade for Action: Water for Life 2005-2015". Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Management Options to Enhance Survival and Growth" (PDF). Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Kummu, M.; Guillaume, J. H. A.; de Moel, H.; Eisner, S.; Flörke, M.; Porkka, M.; Siebert, S.; Veldkamp, T. I. E.; Ward, P. J. (2016). "The world's road to water scarcity: shortage and stress in the 20th century and pathways towards sustainability". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 38495. Bibcode:2016NatSR...638495K. doi:10.1038/srep38495. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5146931. PMID 27934888.

- ^ a b Caretta, M.A., A. Mukherji, M. Arfanuzzaman, R.A. Betts, A. Gelfan, Y. Hirabayashi, T.K. Lissner, J. Liu, E. Lopez Gunn, R. Morgan, S. Mwanga, and S. Supratid, 2022: Chapter 4: Water. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 551–712, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.006.

- ^ Rijsberman, Frank R. (2006). "Water scarcity: Fact or fiction?". Agricultural Water Management. 80 (1–3): 5–22. Bibcode:2006AgWM...80....5R. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2005.07.001.

- ^ IWMI (2007) Water for Food, Water for Life: A Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture. London: Earthscan, and Colombo: International Water Management Institute.

- ^ a b United Nations. Water Scarcity. UN Water.https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/scarcity/

- ^ a b c "The Facts About The Global Drinking Water Crisis". 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Water Scarcity, Risk, and Vulnerability" (PDF). Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "Water". www.un.org. 2015-12-21. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- ^ a b "Archive: Conference on Water Scarcity in Africa: Issues and Challenges". Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e f United Nations. Goal 6: Ensure Access to Water and Sanitation for All. Sustainable Development Goals. https://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/publications/SDG6_SR2018.pdf

- ^ "International Decade for Action: Water for Life 2005-2015". Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Water Scarcity: The Importance of Water & Access". Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ United Nations. (2014, Dec 24). Water Scarcity. International Decade for Action ‘WATER FOR LIFE’. https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/scarcity.shtml

- ^ ISSAfrica.org (2017-05-15). "Africa's population boom: burden or opportunity?". ISS Africa. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- ^ Falkenmark, Malin (1990). "Rapid Population Growth and Water Scarcity: The Predicament of Tomorrow's Africa". Population and Development Review. 16: 81–94. doi:10.2307/2808065. ISSN 0098-7921. JSTOR 2808065.

- ^ World Wildlife Foundation. Water Scarcity. World Wildlife Foundation. https://www.worldwildlife.org/threats/water-scarcity

- ^ a b Chitonge, Horman (2020-04-02). "Urbanisation and the water challenge in Africa: Mapping out orders of water scarcity". African Studies. 79 (2): 192–211. doi:10.1080/00020184.2020.1793662. ISSN 0002-0184. S2CID 221361042.

- ^ a b Wang, Yuan-Xu (2020-08-27). "Runoff pollution control of a sewage discharge project based on green concept – a sewage runoff pollution control system". Water Supply. doi:10.2166/ws.2020.183. ISSN 1606-9749.

- ^ Stocker, Thomas F.; Dahe, Qin; Plattner, Gian-Kasper; Midgley, Pauline; Tignor, Melinda (May 2011). "Tried and tested". Nature Climate Change. 1 (2): 71. doi:10.1038/nclimate1106. ISSN 1758-6798.

- ^ "As Clouds Head for the Poles, Time to Prepare for Food and Water Shocks". World Resources Institute. 2016-07-25. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- ^ a b "Climate Change and Africa" (PDF). Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Water and the global climate crisis: 10 things you should know". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- ^ Stocker, Thomas (2014). Climate change 2013: the physical science basis : Working Group I contribution to the Fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. ISBN 978-1-107-05799-9. OCLC 879855060.

- ^ a b Reinacher, L. (2013 Oct 3). The Water Crisis in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Borgen Project.

- ^ Kumaresan, Jacob; Sathiakumar, Nalini (2010-03-01). "Climate change and its potential impact on health: a call for integrated action". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 88 (3): 163. doi:10.2471/blt.10.076034. ISSN 0042-9686. PMC 2828801. PMID 20428377.

- ^ "The Water Page". Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ a b c "10 Facts About Water Scarcity". Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ Sandy Cairncross (1988). "4". In Douglas Rimmer (ed.). Rural Transformation in Tropical Africa. Great Britain: Belhaven Press. pp. 49–54.

- ^ Bhutta, Z. A.; Ahmed, T.; Black, R. E.; Cousens, S.; Dewey, K.; Giugliani, E.; Haider, B. A.; Kirkwood, B.; Morris, S. S.; Sachdev, H. P. S.; Shekar, M.; Maternal Child Undernutrition Study Group (2008). "What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival". The Lancet. 371 (9610): 417–440. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61693-6. PMID 18206226. S2CID 18345055.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Crow, Ben; Roy, Jessica (2004-03-26). "Gender Relations and Access to Water: What We Want to Know About Social Relations and Women's Time Allocation". Retrieved 18 March 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Impacts of Water Scarcity on Women's Life". Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ a b c "Women Affected by the Crisis". Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Coping With Water Scarcity: Challenge of the 21st Century" (PDF). Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Ahmed, Sara (2005-01-13). SEWA: Campaigning for Water, Women and Work. ISBN 9788175962620. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "In Africa, War Over Water Looms As Ethiopia Nears Completion Of Nile River Dam". NPR. 27 February 2018.

- ^ a b Mabhaudhi, Tafadzwanashe; Chibarabada, Tendai; Modi, Albert (2016). "Water-Food-Nutrition-Health Nexus: Linking Water to Improving Food, Nutrition and Health in Sub-Saharan Africa". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 13 (1): 107. doi:10.3390/ijerph13010107. PMC 4730498. PMID 26751464.

- ^ a b Kauffman, J., Mantel, S., Ringersma, J., Dijkshoorn, J., Van Lynden, G., Dent, D. Making Better Use of Green Water in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- ^ Kadigi, R., Tesfay, G., Bizoza, A., Zinabou, G. (2013). Global Development Network GDN Working Paper Series Irrigation and Water Use Efficiency in Sub-Saharan Africa Working Paper No. 63. Global Development Network. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263464548

- ^ Bain, L., Et al. (2013). Malnutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa: Burden, Causes and Prospects. Pan African Medical Journal. www.panafrican-med-journal.com

- ^ Madungwe, Emaculate; Sakuringwa, Saniso (2007). "Greywater reuse: A strategy for water demand management in Harare?". Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C. 32 (15–18): 1231–1236. Bibcode:2007PCE....32.1231M. doi:10.1016/j.pce.2007.07.015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Africa Rising 21st Century". 2010-02-26. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "The Coming Wars for Water". Report Syndication. October 12, 2019.

- ^ a b c "US Intel: Water a Cause for War in Coming Decades". Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ a b "A Drop In The Bucket". Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Pump Aid-Water For Life". Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Water For People". Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Living Water International". Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "The Play Pump: What Went Wrong?". July 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ "Elephant Pump". Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Water Is Life". Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Lifewater International". Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "International Decade for Action Water for Life 2005-2015: Water Scarcity". Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ a b c "Remarks in Honor of World Water Day". Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ "Water Charities:A Comprehensive List". Retrieved 11 April 2012.