Mundelein College

Mundelein College Skyscraper Building | |

Mundelein College Skyscraper Building as seen from the rear, now part of Loyola University Chicago | |

| Location | 6363 N. Sheridan Rd., Chicago, Illinois |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°59′55″N 87°39′23″W / 41.9985°N 87.6565°W |

| Built | 1930 |

| Architect | Fisher, Nairne W.; McCarthy, Joseph W. |

| Architectural style | Art Deco Skyscraper |

| NRHP reference No. | 80001348 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 31, 1980[1] |

| Designated CL | December 13, 2006 |

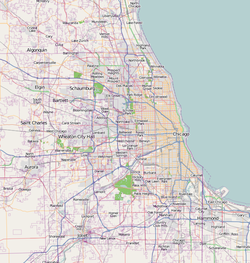

Mundelein College was the last private, independent, Roman Catholic women's college in Illinois. Located on the edge of the Rogers Park and Edgewater neighborhoods on the far north side of Chicago, Illinois, Mundelein College was founded and administered by the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. In 1991, Mundelein College became an affiliated college of Loyola University Chicago. It has since become completely incorporated. Mundelein College was located just south of Loyola's Lake Shore Campus.

History

On November 1, 1929, three days after the stock market crash, the official ground-breaking ceremony for Mundelein College was held. Even if the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (BVM) had been able to see the Great Depression coming, there was no stopping construction on the skyscraper building at 6363 North Sheridan Road; the first four floors of the building were already in place. Despite the financial hardships of the time Mundelein College opened its door for class registration only nineteen months after construction began on September 15, 1930. Due to the overwhelming number of students, the first day of classes had to be delayed until October 3, 1930. At the close of the college's first academic year, on June 3, 1931, traffic was rerouted, the uniformed bands of St. Mary's High School and Immaculata High School played on the front steps, and the Knights of St. Gregory escorted Cardinal George Mundelein to Mundelein College's official dedication ceremony.[2]

Mundelein College grew out of the aspirations of both the BVM sisters and Cardinal Mundelein. Upon his placement to the position of archbishop of Chicago, Cardinal Mundelein made the education of Catholics one of his primary goals.[3] Meanwhile, the growth of the BVM order of sisters had outpaced the educational ability of Mount Saint Joseph, the BVM college in Dubuque, Iowa. The successful partnership between Cardinal Mundelein and the BVM superior general, Mother Mary Isabella Kane, BVM, led to a college which would exceed both their aspirations. Unable to be in both Iowa at the BVM motherhouse and Chicago, Mother Isabella Kane, BVM appointed Sr. Mary Justitia Coffey, BVM to oversee all matters related to the development of Mundelein College. A year later Sr. Mary Justitia Coffey, BVM became the first superior and president of the college.[4]

During the first few decades, Mundelein College resembled many other women's colleges in the United States. College courses offered covered both traditional liberal arts and practical life skills, ranging from Latin, philosophy, literature, physics, and chemistry to home economics and secretarial skills. In the 1940s the Mundelein College Skyscraper boasted one of the country's highest observatories containing a telescope and the longest Foucault pendulum in existence at the time.[5] Clubs were a major part of student life at Mundelein. In the first decade, twenty-two clubs were created, ranging from the Stylus (writing) Club and basketball team to the Chemistry Club and International Relations. The Verse Speaking Choir worked under contract with NBC Radio and its participants included Mercedes McCambridge (1937), Academy Award and Golden Globe winner.[6]

Upon the United States entry into World War II the Mundelein College student body participated in a variety of war effort activities. In addition to planting a victory garden near the library, Mundelein students held a jeep drive which raised funds equivalent to the cost of two United States Army Jeeps, held several blood drives, and purchased a war bond with the proceeds from their annual benefit. Mundelein College students also started the first Midwest college unit of the American Red Cross.[7]

In 1957 Sr. Mary Ann Ida Gannon, BVM became Mundelein College's sixth president and Mundelein College began a new phase of development. That year 48 young sisters began their education side by side with Mundelein College's lay student population as part of the scholasticate program. Also that year Sr. Mary Ann Ida Gannon, BVM asked Sr. Mary Carol Frances Jegen, BVM to establish Mundelein College's first theology department.[8][page needed]

Sr. Mary Ann Ida Gannon, BVM initiated a college wide self-study in 1962 to determine Mundelein College's continued relevance as an institution of higher academic education. The results of the self-study became the driving force for several experimental programs. Mundelein College updated its mission statement, redesigned its term system and core curriculum. In 1965, the college implemented a Degree Completion Program for women who had dropped out of college before receiving their degrees. Beginning with the academic year 1970–71, the college offered students a self-directed course of study, within a group known as "Mandala." By 1974, the Weekend College in Residence program expanded upon the idea of the Degree Completion Program by offering working women the opportunity to achieve a degree while attending college only on the weekends.[8]

Although Mundelein College had amended their articles of incorporation in 1968 to admit men, the education and cultivation of women remained its primary focus. Mundelein College was not immune to the forces of feminism and in 1977 the seeds of an interdisciplinary women's studies program began to germinate. Over the next two years, Mundelein College held yearly conferences on women. However, it wasn't until 1983 that a Women's Studies minor was finally accepted by the college Curriculum Committee. The Peace Studies minor, inaugurated in 1989, also integrated feminist perspectives.[8]

The decades between 1960 and 1990 also saw an increase of minority outreach at Mundelein College. In 1966, the college launched Upward Bound, a federally funded summer program to help minority high school students succeed to college. Responding to the death of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, black students at Mundelein College formed MuCUBA (Mundelein College United Black Association) to address the racial barriers which existed within the walls of the college. In 1982 Hispanic students created their own organization, Hispanics for the Advancement of Our Culture and Education (later reorganized into Latins United for Our Cultural Heritage).[8]

Many Mundelein students embraced the spirit of activism in the 1960s and 1970s. Seven BVMs and "a busload" of students traveled to Alabama to participate in the Selma March for Civil Rights.[9] Mundelein College's student body participated in the national wide strike protesting the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia and the student deaths at Kent State University. Students and faculty marched from the Learning Resource Center to the Skyscraper in solidarity against the war.[10] In November 1979, César Chávez spoke at Mundelein College during his tour around the country promoting a lettuce workers strike.

The opening of the 1980s saw Mundelein College celebrating its 50th anniversary with great fanfare. Among the dignitaries at the Golden Jubilee Dinner was Mayor Jane Byrne and highlighting the event was the appearance of Mother Teresa, recipient of the 1980 Magnificat Medal.[11] New programs continued to enhance Mundelein's academic offerings, including courses in food management, interior architecture and design, communications, computer science, and peace studies.

Presidents

| President | Term |

|---|---|

| Sr. Mary Justitia Coffey, BVM | 1930–1936 |

| Sr. Mary Consuela, BVM | 1936–1939 |

| Sr. Mary Justitia Coffey, BVM | 1939–1945 |

| Sr. Mary Josephine Malone, BVM | 1945–1951 |

| Sr. Mary John Michael Dee, BVM | 1951–1957 |

| Sr. Mary Ann Ida Gannon, BVM | 1957–1975 |

| Sr. Susan Rink, BVM | 1975–1983 |

| Dr. John Richert, the only non-BVM President of Mundelein | 1983–1985 |

| Sr. Mary Brenan Breslin, BVM | 1985–1991 |

| Sr. Carolyn Farrell, BVM | 1991-Affiliation |

Campus

The Skyscraper

When new, the fourteen-story Art Deco building dominated the skyline of Chicago's far north side. The Skyscraper had few equals in size and style outside of Downtown Chicago (similarly designed buildings include the Palmolive Building, the Chicago Board of Trade Building, and the West Town Bank Building). Vertical lines of Indiana limestone created a visual illusion making the college appear to soar higher than its actual 198 feet (60 m).[12]

Although the Skyscraper features abstracted foliate, sunbursts, and other geometric designs around its doors and windows, the most striking feature of the building's exterior is its guardian angels. The two towering statues at the entrance represent the angels Uriel ("Light of God") and Jophiel ("Beauty of God"). Uriel holds the book of wisdom and points to a cross in Bas-relief on the fourteenth floor. Jophiel holds the planet Earth and lifts the torch of knowledge.[13]

Although Chicago architect Joseph W. McCarthy is listed as the supervising architect, the building was designed by Nairne W. Fisher, from St. Cloud Minnesota. McCarthy had been Cardinal Mundelein's choice. However, after Mother Isabella Kane dismissed McCarthy's Gothic Revival design, she turned to Fisher with whom she had worked before. Not only was Fisher's design more modern, it was less expensive than McCarthy's.[4]

Fisher studied drafting at a Minneapolis technical school, served in a U.S. Army Intelligence unit which produced maps during World War I, studied briefly at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, worked as a draftsman at lumberyards in Minnesota and South Dakota, and registered as a Minnesota architect in 1922. The designer of the "Moderne" (later known as Art Deco) Mundelein College building never graduated from college.[14]

Originally intended to be a self-contained educational facility, the interior contained classrooms, laboratories, art and music studios, a library, an auditorium, a chapel, a cafeteria, a swimming pool, a gymnasium, reception areas and meeting rooms, and seven floors of living quarters for the BVM staff. Beginning in 1934 with the two houses east of the Skyscraper, Mundelein College began expanding.[15] By 1991, in addition to the original skyscraper, Mundelein College owned a dormitory (Coffey Hall), the white marble mansion (Piper Hall), the Learning Resource Center (now the Sullivan Center), the Yellow House (also known as the President's House), and a residence for the BVMs (Wright Hall).

The Mundelein College Skyscraper was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.[16]

In December 2007 the City of Chicago designated the building as an official Chicago landmark[permanent dead link].[17]

Starting in 2005, the Skycraper Building went through an almost 10 year renovation process modernizing the facility while retaining much of its original deco architectural beauty. In October 2012 the building was rededicated the Mundelein Center for the Fine and Performing Arts. It currently houses the specialized facilities of the Fine and Performing Arts Department of Loyola, and now features a new café, green roof and modern thrust stage, multimedia classrooms, offices, galleries, and event spaces in addition to being the largest academic classroom building on Loyola's Lakeshore Campus.

Residence halls

Although Mundelein College began offering some student housing within the upper floors of the Skyscraper shortly after the college opened, the first official student residence hall was purchased in 1934. Known as Philomena Hall, the twelve-room brick building was one of two mansions separating the Skyscraper from Lake Michigan. Philomena served as a residence hall until 1959 when it was converted into a speech clinic, Student Activities Council official headquarters, and a senior smoker study hall.[18]

In 1961, Philomena Hall was razed to make room for Mundelein College's newest dormitory, Coffey Hall. Opened for occupation in 1962, the new residence hall accommodated 208 students.[19] More recently, Coffey Hall briefly served as dormitory for Loyola University Chicago students, with its last year of residents in the 2008–2009 school year. Coffey Hall has since been renovated for use as department office space. In 1963, Mundelein College purchased Northland Apartments to the west of the Skyscraper. Northland Hall housed a further 250 students. Loyola University Chicago razed Northland Hall in 1992 in order to create a new campus entry.[20]

Libraries

The original library was housed in room 401 of the Skyscraper building. Stocked mainly with donated books, the entire initial library collection was cataloged and shelved in only thirty days. The main book donation came from Rev. John Rothensteiner of St. Louis. The initial donation consisted of 2,000 volumes; however, he later bequeathed his entire 20,000 volume library to the college. This gift was the heart of Mundelein College's rare book collection.[4]

Mundelein College moved its library in 1934 to the white marble mansion purchased from Albert Mussey Johnson. Reading rooms occupied the first two floors of the mansion while the former ballroom on the third floor housed the book stacks. The white marble mansion remained the college's library until 1967. After the books were removed from the mansion, it took on multiple personalities including a student center, a coffee shop, a speech clinic (after Philomena was razed), and the Religious Studies Center. After a 2005 remodeling, the white marble mansion is currently Loyola University Chicago's Piper Hall (see below).[21]

The crowning jewel in the fast-paced growth of the campus during the 1960s, the Learning Resource Center, built in 1967, became Mundelein College's new library. Officially dedicated in 1969, the Learning Resource Center provided Mundelein students with a science and lecture auditorium, 100-seat audiovisual room, faculty and student lounges, seminar rooms, and a rare book room. Today the Learning Resource Center serves the Loyola University Chicago community as the Sullivan Center for Student Services.[22]

Affiliation with Loyola University

Enrollment in Mundelein College dropped dramatically in the 1980s. By the end of the decade, the college could no longer financially support itself. In 1991, Mundelein College became an incorporated college of neighboring Loyola University Chicago.

The ideals and values of the BVM sisters continue through the Gannon Center for Women and Leadership, established by Loyola University Chicago. The Gannon Center located in Piper Hall is home to the Gannon Scholars program (a leadership training organization for twenty female Loyola students), the Women's Studies Department, and the Women and Leadership Archives.

Notable faculty

- Sister Jean Dolores Schmidt, BVM, chaplain of Loyola University Chicago's men's basketball team who became popular during their Final Four run in 2018

Notable students

- Tina De Rosa, author of Paper Fish (Sociology Major)[23]

- Arlene Halko, medical physicist and gay rights activist

- Mercedes McCambridge, award-winning actress

- Jane Trahey, pioneering female advertising executive

- Martha M. Vertreace-Doody Chicago poet

See also

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ Ann M. Harrington and Prudence Moylan, ed., Mundelein Voices: The Women's College Experience, 1930–1991 (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 2001).

- ^ Edward R. Kantowicz, Corporation Sole: Cardinal Mundelein and Chicago Catholicism (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1983).

- ^ a b c Harrington and Moylan, ed., Mundelein Voices.

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. F.5..23e. Foucault Pendulum

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. N.4..1 Skyscraper Vol. 12-16, 1941–1946

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. N.4..1 Skyscraper Vol. 12-16, 1941-1946, and Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. B.1..3g. 2006 Chicago Landmark Application.

- ^ a b c d Prudence Moylan, "A Catholic Women's College Absorbed by a University: The Case of Mundelein College", in Challenged by Coeducation: Women's Colleges Since the 1960s (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2006).

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives. Mundelein College Record Collection. M.4..2. Selma March, 1965.

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. M.4..3c. College "Strike", May 1970.

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. O.2..3e.2 Mother Teresa files.

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. B.1..3g. 2006 Chicago Landmark Application.

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. A4..1b. Angels.

- ^ Nairne W. Fisher, "My Life, 1899 to 1972 (written May 1972).

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. B4..1 History/Scotty's Story.

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. B.1..3a. Letter of Approval, April 1980.

- ^ City of Chicago, Department of Planning and Development "Lofty designation approved for Mundelein College skyscraper[permanent dead link]", December 13, 2006

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. B.5 Philomena Hall.

- ^ Moylan. "A Catholic Women's College Absorbed by a University."

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. B.9 Northland.

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. B.4 Wheeler/Johnson/Gannons/Piper Hall.

- ^ Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Mundelein College Record Collection. B. 10 Learning Resource Center.

- ^ Lauerman, Connie. "Lady In Waiting." Chicago Tribune. September 2, 1996. p. 2. Retrieved on March 14, 2014.

External links

- Loyola University Chicago

- Embedded educational institutions

- Educational institutions established in 1930

- Educational institutions disestablished in 1991

- School buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Chicago

- Art Deco architecture in Illinois

- Defunct private universities and colleges in Illinois

- University and college buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Illinois

- 1930 establishments in Illinois

- 1991 disestablishments in Illinois

- Former women's universities and colleges in the United States

- Mundelein College