Shanghai Manhua

Cover of the first issue: Cubist Shanghai Life by Zhang Guangyu | |

| Categories | Manhua |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Weekly |

| Circulation | 3,000 |

| First issue | 21 April 1928 |

| Final issue | 7 June 1930 |

| Company | Shanghai Sketch Society |

| Country | Republic of China |

| Based in | Shanghai |

| Language | Chinese |

Shanghai Manhua (traditional Chinese: 上海漫畫; simplified Chinese: 上海漫画; pinyin: Shànghǎi Mànhuà), originally titled Shanghai Sketch, was a weekly pictorial magazine published in Shanghai from 21 April 1928 until 7 June 1930.[1] Considered the first successful manhua magazine in China[2] and one of the most influential,[3] it was highly popular and inspired numerous imitators in Shanghai and the rest of China.[4] Shanghai Manhua was known for its provocative cover art and the popular Mr. Wang comic strip by Ye Qianyu.[1][5]

History

Founding

Among the artists who established Shanghai Manhua, several had worked together on the small, short-lived journal Sanri Huabao (Three Day Pictorial), including Ye Qianyu and the brothers Zhang Guangyu and Zhang Zhenyu. The journal was shut down when Chiang Kai-shek's Northern Expedition reached Shanghai in April 1927.[1]

Out of work, cartoonists Ye Qianyu, Huang Wennong, and Lu Shaofei published a dedicated publication for manhua named Shanghai Manhua (Shanghai Sketch). The first effort resembled a propaganda poster and was a failure. Undeterred, the original three, joined by eight more artists, including the Zhang brothers, Ding Song, and Wang Dunqing, formed the Shanghai Sketch Society (also translated as Shanghai Manhua Society) in the autumn of 1927.[1] It was China's first association dedicated to manhua and a major event in the history of Chinese comics.[6]

Although the society had no formal structure, the two eldest and most established artists, Zhang Guangyu and Ding Song, were regarded as its leaders. The society was registered and often met at Ding Song's home on Rue Amiral Bayle (now South Huangpi Road).[7]

Under the leadership of Zhang Guangyu, who recruited sponsors including the wealthy poet Shao Xunmei,[1] the association relaunched Shanghai Manhua on 21 April 1928.[7] It proved very popular: about three thousand copies of each issue were printed, which was considered a large amount for the 1920s.[1]

Demise

In 1930, a Singapore-based businessman made a proposal to Zhang Guangyu and Zhang Zhenyu for starting a new pictorial magazine to compete with the popular monthly The Young Companion (Liangyou). The Zhang brothers agreed, but several partners in charge of photography objected.[8] As a result of the dispute, Shanghai Manhua was shut down in June 1930 after publishing 110 issues.[7] The manhua team of the magazine moved with the Zhangs to the newly established Shidai (Epoch) Publishing Group, which went on to publish a series of magazines including Modern Sketch, the centerpiece of China's golden era of cartoon art.[5]

In May 1936 Zhang Guangyu re-established Shanghai Manhua, while many of the original members were then working with Modern Sketch.[3] Together they organized the highly successful First National Cartoon Exhibition in September and formed the National Association of Chinese Cartoonists in the spring of 1937. The blossoming movement, however, was brought to a halt by the Japanese invasion a few months later.[3]

Format

Each issue of the magazine consists of eight pages including the front and back covers.[7] The front cover featured its famously provocative cover art,[5] and the back page carried Ye Qianyu's popular comic strip Mr. Wang, inspired by the American Bringing Up Father. Reflecting the tribulations of daily urban life, Mr. Wang became one of China's most famous cartoons.[1] Pages four and five were dedicated to other cartoons from various artists, and the remaining four pages were flexibly given to manhua, photography, prose, reviews, etc.[7]

Influence

In addition to members of the Shanghai Sketch Society, other famous artists and writers also contributed to Shanghai Manhua, including Shao Xunmei (Sinmay Zau), a wealthy and influential poet, writer, and publisher. His friend, artist and writer Ye Lingfeng, also became a staff member and regular contributor. Their photographs were frequently published in the magazine, with some taken by the photographer Lang Jingshan.[1]

Many of the images published in Shanghai Manhua reflect the daily urban life, while others are innovative visual commentaries on political events and contemporary society.[1] The editorial staff of the magazine had close links to leading members of the decadent "neo-sensationist" school of the Shanghai literary scene. Influenced by ideas expressed in their writing, the artists produced startling images unparalleled in Republican-era China.[1]

Selected cover art

-

Huang Wennong: Offer Temptation, Receive Infatuation, 28 April 1928

-

Ye Qianyu: Unfortunate Love, 16 June 1928

-

Ye Lingfeng: Untitled, 29 Dec 1928

-

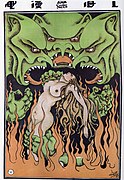

Zhang Zhenyu: Untitled, 29 June 1929

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Laing, Ellen Johnston (October 2010). "Shanghai Manhua, the Neo-Sensationist School of Literature, and Scenes of Urban Life". Ohio State University. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ Petersen, Robert S. (2011). Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels: A History of Graphic Narratives. ABC-CLIO. p. 120. ISBN 9780313363306.

- ^ a b c 漫画 [Manhua]. Shanghai Chronicle (in Chinese). Shanghai Municipal Government. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ Wong, Wendy Siuyi (2002). Hong Kong Comics. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 18. ISBN 9781568982694.

- ^ a b c Crespi, John A. (2011). "China's Modern Sketch, the Golden Era of Cartoon Art". MIT. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ Hung, Chang-tai (1994). War and Popular Culture: Resistance in Modern China, 1937–1945. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520082366.

- ^ a b c d e 《上海漫画》 [Shanghai Manhua] (in Chinese). Phoenix TV. 25 December 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ Ye Qianyu (2006). "《上海漫画》的最后命运". 叶浅予自传: 细叙沧桑记流年 [Autobiography of Ye Qianyu] (in Chinese). China Social Science Publishing House. ISBN 9787500453109. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

External links

Media related to Shanghai Manhua at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Shanghai Manhua at Wikimedia Commons

- 1928 establishments in China

- 1930 disestablishments in China

- 1928 comics debuts

- 1930 comics endings

- Chinese-language magazines

- Weekly magazines published in China

- Defunct magazines published in China

- Magazines established in 1928

- Magazines disestablished in 1930

- Magazines published in Shanghai

- Manhua magazines